Abstract

Rationale

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) represents a serious health complication accompanied with hypoxic conditions, elevated levels of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), and overall dysfunction of pulmonary vascular endothelium. Since the prevention strategies for treatment of PH remain largely unknown, our study aimed to explore the effect of nitro-oleic acid (OA-NO2), an exemplary nitro-fatty acid (NO2-FA), in human pulmonary artery endothelial cells (HPAEC) under the influence of hypoxia or ADMA.

Methods

HPAEC were treated with OA-NO2 in the absence or presence of hypoxia and ADMA. The production of nitric oxide (NO) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) was monitored using the Griess method and ELISA, respectively. The expression or activation of different proteins (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3, STAT3; hypoxia inducible factor 1α, HIF-1α; endothelial nitric oxide synthase, eNOS; intercellular adhesion molecule-1, ICAM-1) was assessed by the Western blot technique.

Results

We discovered that OA-NO2 prevents development of endothelial dysfunction induced by either hypoxia or ADMA. OA-NO2 preserves normal cellular functions in HPAEC by increasing NO production and eNOS expression. Additionally, OA-NO2 inhibits IL-6 production as well as ICAM-1 expression, elevated by hypoxia and ADMA. Importantly, the effect of OA-NO2 is accompanied by prevention of STAT3 activation and HIF-1α stabilization.

Conclusion

In summary, OA-NO2 eliminates the manifestation of hypoxia- and ADMA-mediated endothelial dysfunction in HPAEC via the STAT3/HIF-1α cascade. Importantly, our study is bringing a new perspective on molecular mechanisms of NO2-FAs action in pulmonary endothelial dysfunction, which represents a causal link in progression of PH.

Keywords: Nitro-oleic acid, Asymmetric dimethylarginine, Hypoxia, Pulmonary hypertension, Human pulmonary artery endothelial cell

Introduction

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a progressive vasculopathy with high prevalence in certain at-risk groups (e.g. patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cystic fibrosis, systemic sclerosis, sickle cell disease, and HIV) [1–5]. Nowadays, it is well accepted that PH is linked with endothelial dysfunction, caused by imbalance in vasoactive mediators (e.g. nitric oxide, NO and prostaglandin I2), increased production and expression of inflammatory molecules (such as inter-leukin-6, IL-6 and intracellular adhesion molecule 1, ICAM-1) as well as activation of various pro-inflammatory and pro-proliferative signaling pathways (including signal transducer and activator of transcription 3, STAT3 and hypoxia-inducible factor 1-α, HIF-1α) (reviewed in [2]).

Importantly, it has also been discovered that PH is accompanied by increased systemic levels of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), an endogenous inhibitor of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), which serves as a predictor of mortality in patients with PH [4–7]. Recently, ADMA levels have been found to be increased in human pulmonary artery endothelial cells (HPAEC) exposed to hypoxia, showing the possibility that ADMA might serve as an intermediary molecule in hypoxic effects [8]. Our group has also shown that it represents a critical regulator of human pulmonary vascular functions. ADMA decreased the bioavailability of NO via inhibition of activation and expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), responsible for NO synthesis in HPAEC [9]. Additionally, ADMA caused the up-regulation of pro-inflammatory mediator production (IL-6; ICAM-1; platelet-derived growth factor, PDGF; and Regulated on Activation Normal T cell Expressed and Secreted, RANTES) via STAT3/HIF-1α signaling cascade, resulting in development of PH phenotype in HPAEC [9]. Based on the above-mentioned findings, we suggest that ADMA and STAT3/HIF-1α cascade are potential therapeutic targets for future clinical interventions in PH.

Evidence implies that nitro-fatty acids (NO2-FAs), known for their pleiotropic anti-inflammatory, anti-proliferative, and cardioprotective actions [10–13] are suitable candidates for prevention of hypoxia- and ADMA-enhanced PH phenotype in endothelial cells (ECs). Electrophilic NO2-FAs induce reversible post-translational modification of susceptible nucleophilic amino acids of proteins via Michael addition and they are expected to influence numerous signaling pathways (including STATs; nuclear factor-κB, NF-κB; mitogen activated protein kinases, MAPKs; Kelch ECH associating protein 1/nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2, Keap1/Nrf2 system, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ, PPAR-γ) [10, 11, 14, 15]. NO2-FAs inhibit cell proliferation; reduce infarct size, atherosclerotic plaque development, macrophage activation in murine models of cardiac ischemia and reperfusion, atherosclerosis as well as systemic hypertension [10, 11, 13]. Importantly, our recent study indicated that NO2-FAs are able to prevent hypoxia-induced PH in a mouse model [16]. To help to elucidate molecular mechanisms of this phenomenon, an in vitro model of hypoxia-induced PH was employed in our study.

Therefore, we decided to be the first to examine the effect of nitro-oleic acid (OA-NO2), an exemplary NO2-FA, in our recently published hypoxia- and ADMA-induced model of endothelial dysfunction [9], which represents a highly suitable environment for testing the ability of different compounds to interfere with the development of the PH phenotype in human primary cells. Our experiments were focused on determination of specific molecules and proteins (NO, eNOS, IL-6, and ICAM-1), detection of adhesive properties and migration activity of HPAEC as well as on activation of specific signaling cascades (STAT3/HIF1a) involved in the development of PH [2, 17–19].

Material and Methods

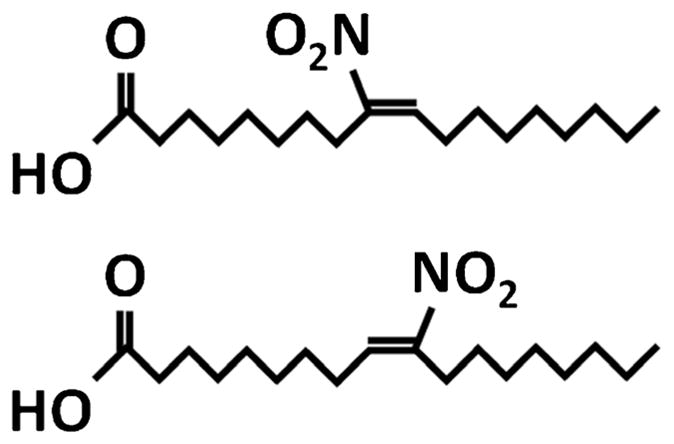

Unless otherwise stated, all chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The OA-NO2 (mixture of isomers (E)-9- and 10-nitro-octadec-9-enoic acid; for structure see Fig. 1) was provided by the Department of Pharmacology & Chemical Biology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh PA, USA. The OA-NO2 was diluted up to 100 mM solution in concentrated methanol and stored at −80 °C. For experimental application, 10 mM solution of OA-NO2 in methanol was prepared and diluted in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; PAN-Biotech, Aidenbach, Germany) to obtain 100 μM OA-NO2. The fresh solution of OA-NO2 was used immediately for treatment of cells [20]. In our experiments we used final concentration 1.0 μM. All stocks were prepared in sterile low-binding tubes.

Fig. 1.

Structure of OA-NO2 isomers. (E)-9-nitro-octadec-9-enoic acid and (E)-10-nitro-octadec-9-enoic acid

Cell Cultures

HPAEC (Lonza, Switzerland) were cultivated in complete EGM™-2 medium (Lonza). Confluent cells at passage 2–5 were used for the experiments. Experiments were performed in basic medium supplemented with 2 % of fetal bovine serum (FBS).

Detection of Cell Viability

Cell viability was measured based on total cellular mass of adherent cells using the detergent-compatible protein assay reagent (Bio-Rad, USA) with bovine serum albumin as a standard [9]. Cell viability was not significantly decreased in any of the tested groups (data not shown).

Determination of NO Production

The production of nitrites (the end product of NO metabolism in cultivation medium) was measured by the Griess assay [9]. Equal volume of supernatants (150 μl) and Griess reagent were mixed and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The absorbance (540 nm) was measured using SPECTRA Sunrise microplate reader (Tecan, Mannedorf, Switzerland).

Detection of Protein Expression Using a Western Blot Technique

The expression of proteins was detected in cell lysates as described previously [9]. Briefly, an equal amount of proteins (25 μg) was loaded to 10 % SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to immobilon polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilon-P, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Membranes with transferred proteins were incubated with primary antibodies against phospho-STAT3 (pSTAT3, Tyr705), STAT3, eNOS (Cell Signaling Technology, USA) or against ICAM-1 and HIF-1α (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA). Membranes incubated with secondary antibody were visualized into CP-B X-ray films (Agfa, Brno, Czech Republic). Relative levels of proteins were analyzed and quantified using the ImageJ™ program (National Institutes of Health, USA). Individual band density value is expressed in optical density. An equal protein concentration was verified by blotting of β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The data in graphs represent the ratio between the individual values for OD of bands determined for phosphorylated and total form of protein and total form against β-actin.

Quantitative Determination of the Cytokine Levels

Concentration of human IL-6 was measured by commercially available human ELISA DuoSet kit (R&D Systems, USA). Cell supernatants were processed in agreement with supplier’s instructions [20].

Characterization of Migration Activity

The migration of HPAEC was detected using the scratch-wound assay, which is simple and commonly used to measure basic cell migration parameters. HAPEC were grown to confluence and a thin cross was introduced by scratching a pipette tip. The migration of cells into the cross-space was monitored after 24 h and was analyzed and quantified using the ImageJ™ program (9).

Characterization of Adhesive Properties

For the adhesion experiments, HPAEC were cultured in 96-well tissue culture plates (Genetix, USA) until confluent. HPAEC were left either unstimulated or stimulated for 24 h with or without ADMA (100 μM) and/or OA-NO2 (1.0 μM). Isolated human neutrophils were loaded with fluorescent dye-calcein-AM (1 μM) for 20 min at 37 °C in the dark and washed. The adhesion of neutrophils to HPAEC was quantified under static conditions. Before the adhesion assay was performed, HPAEC were washed and basic medium supplemented with 2 % FBS was applied to cells. Labeled neutrophils were applied at a density of 5 × 103 cells/well to the HPAEC surface and allowed to adhere for 1 h at 37 °C with gentle rocking. Non-adherent cells were removed by washing two times with HBSS. The relative fluorescence intensity of adherent neutrophils was analyzed by an Infinite M200 microplate spectrofluorimeter with excitation and emission wavelengths of 480 and 530 nm (21). Results are displayed as % of positive control (tumor necrosis factor-α, 50 ng/ml).

Data Analysis

Data were statistically analyzed using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), which was followed by Bonferonni’s multiple comparison test (GraphPad Prism 5.01). All data are reported as means ± SEM. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. The statistical comparison is represented as follows: in all the graphs, letter a represents the significant difference between a group of data in the first bar and a group of data in the other bars, b represents the significant difference between the second and the other bars, c represents the significant difference between the third and the other bars and d represents the significant difference between the fourth and the other bars.

Results

The effect of OA-NO2 was tested in the well-established model of HPAEC exposed to hypoxia [8, 9, 16] or ADMA [9]. The control group represented HPAEC cultivated under normoxic conditions (21 % of O2, 5 % of CO2), which were not exposed to ADMA or OA-NO2. Another group of cells was treated with OA-NO2 (1.0 μM) under normoxic conditions. Further, the cells were exposed to hypoxic conditions (5 % of O2, 90 % of N2, 5 % of CO2) or ADMA (100 μM). The last group of cells was exposed to combination of hypoxia or ADMA together with OA-NO2 (1.0 μM). The treatment conditions were selected based on our previously published results [16, 20].

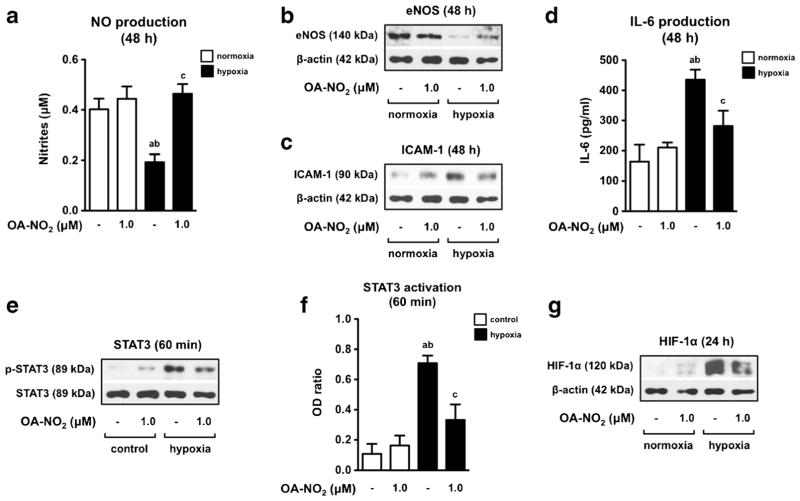

OA-NO2 Prevents Hypoxia-Induced Endothelial Dysfunction and Activation of Intracellular Signaling Pathways in HPAEC

As we expected, hypoxia (5 % of O2) induced a significant decrease in NO production as well as eNOS expression determined in cells cultivated for 48 h (Figs. 2a, b). Moreover, hypoxia caused an increased production of IL-6 (Fig. 2c) and expression of ICAM-1 (Fig. 2d). Further, hypoxia-induced pro-inflammatory phenotype in ECs was effectively prevented by OA-NO2 (1.0 μM) (Fig. 2a, b, c and d).

Fig. 2.

OA-NO2 prevents hypoxia-induced endothelial dysfunction. ECs were treated with OA-NO2 under normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 60 min, 24 h, and 48 h. OA-NO2 affects nitrite accumulation (n = 6) a, eNOS b and ICAM-1 expression c, production of IL-6 (n = 6) d, STAT3 activation e, f as well as stabilization of HIF-1α g. The pictures represent one of three individual experiments. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical comparison is represented as follows: a, b, and c represents the group of data statistically significant when compared to the data in the first (a), second (b), and third (c) bar, respectively

In the following experiments we confirmed our recently published observation [9] that hypoxia-induced PH phenotype in HPAEC is connected with increased phosphorylation of STAT3 (60 min) (Fig. 2e, f) and consequent stabilization of HIF-1α (24 h) (Fig. 2g). We discovered that OA-NO2 (1.0 μM) was able to effectively prevent these processes, indicating the potential usage of OA-NO2 in prevention of hypoxia-induced PH manifestation in HPAEC (Fig. 2e, f and g).

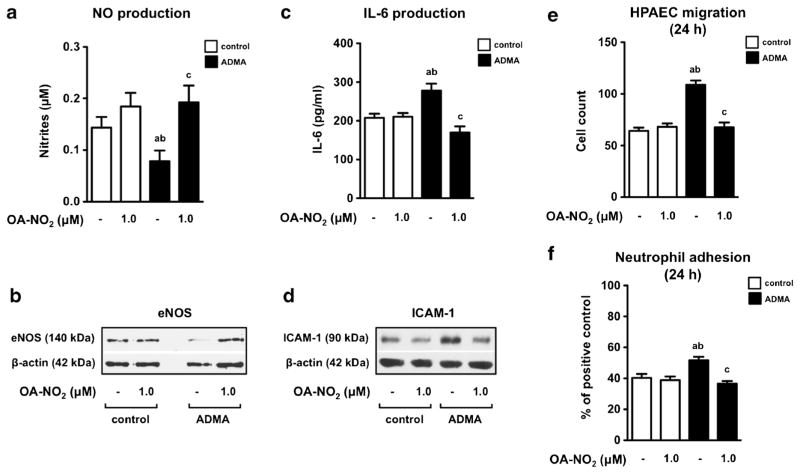

OA-NO2 Prevents ADMA-Induced Endothelial Dysfunction in HPAEC

Similar experiments were performed with ADMA. As we had expected, ADMA (100 μM) was also able to trigger the PH phenotype in HPAEC treated for 48 h (Fig. 3) [9]. Importantly, OA-NO2 (1.0 μM) completely prevented ADMA-induced endothelial dysfunction, characterized by a significant decrease in NO production (Fig. 3a) and eNOS expression (Fig. 3b) as well as an enhanced production of IL-6 (Fig. 3c) and an increased expression of ICAM-1 (Fig. 3d). Moreover, we found that OA-NO2 effectively downregulates the ADMA-induced migration of HPAEC to the wound space (Fig. 3e, Suppl. 1) as well as the ability of human neutrophils to adhere to HPAEC (Fig. 3f, Suppl. 2).

Fig. 3.

OA-NO2 prevents ADMA-induced endothelial dysfunction in HPAEC. Endothelial cells were treated with OA-NO2 in combination with ADMA (100 μM) for 24 or 48 h. Nitrite accumulation a and IL-6 production c were detected in culture medium (n = 6). Expression of eNOS b and ICAM-1 d were assessed in cell lysates. The pictures represent one of three individual experiments. Migration of HPAEC (n = 3) e and adhesion of human neutrophils to HPAEC (n = 4) f were assed after 24 h of cell incubation. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant and the statistical comparison is represented as follows: a, b, and c represents the group of data statistically significant when compared to the data in the first (a), second (b), and third (c) bar, respectively

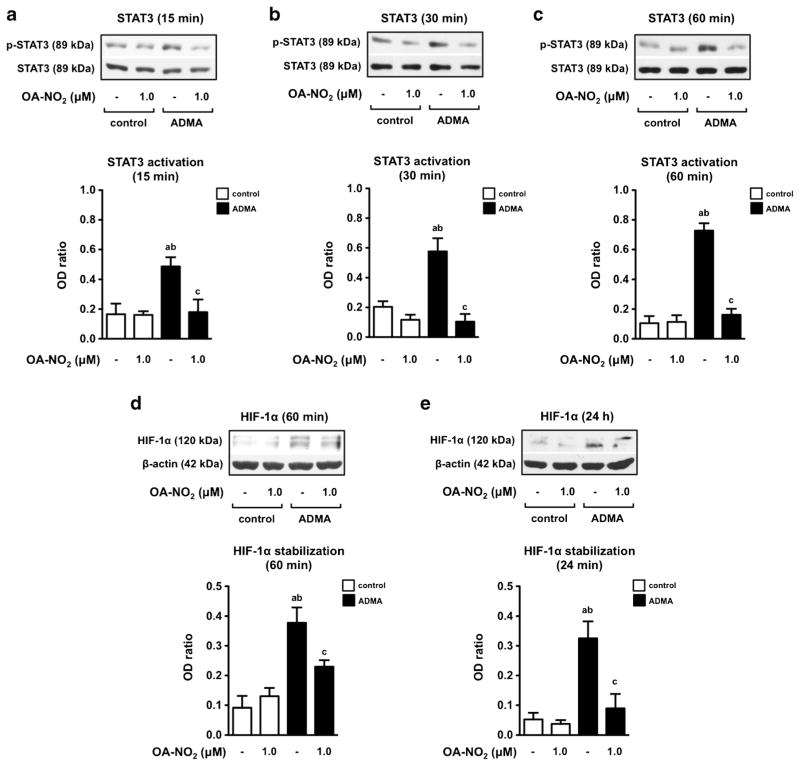

Next, we examined the potential involvement of OA-NO2 in ADMA-mediated activation of STAT3/HIF-1α signaling pathway, shown to be involved in development of PH phenotype in human endothelial and smooth muscle cells [9]. Expression and activation of STAT3 was determined in HPAEC exposed to ADMA (100 μM) and/or OA-NO2 (1.0 μM) for 15, 30, and 60 min (Fig. 4a, b and c). Additionally, stabilization of HIF-1α was assessed at 60 min and 24 h after cell incubation (Fig. 4d, e). We discovered that OA-NO2 completely abolished the ADMA-upregulated phosphorylation of STAT3 (Fig. 4a, b and c). This phenomenon was accompanied with OA-NO2-mediated prevention of ADMA-induced HIF-1α stabilization in both time points selected (Fig. 4d, e).

Fig. 4.

OA-NO2 prevents ADMA-induced activation of intracellular signaling pathways in HPAEC. The cells were treated with OA-NO2 in combination with ADMA (100 μM) at different time points. OA-NO2 affects activation of STAT3 a, b, and c and stabilization of HIF-1α d and e. The pictures represent one of three individual experiments. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical comparison is represented as follows: a, b, and c represents the group of data statistically significant when compared to the data in the first (a), second (b), and third (c) bar, respectively

Discussion

This study was conducted to uncover the role of NO2-FAs in prevention of PH phenotype induced in HPAEC. The effect of OA-NO2 was tested in our previously established model of hypoxia- and ADMA-mediated endothelial dysfunction [9]. The current study brought unique results which showed that OA-NO2 is able to critically regulate pulmonary EC functions. This conclusion is based on several important findings. (1) We showed for the first time that OA-NO2 (1.0 μM) prevents hypoxia- and ADMA-induced downregulation of NO production as well as eNOS expression. It is well known that hypoxia and ADMA reduce NO bioavailability by affecting enzyme activity as well as protein expression of eNOS [9, 20, 21], which is in accordance with results presented in this study. Interestingly, it has been previously described that at higher concentrations, NO2-FAs (3.0–5.0 μM) might be a direct source of NO, mediating endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation [22–25], however in vivo NO2-FAs do not acutely affect blood pressure or heart rate [11, 13]. In our study, OA-NO2 had no effect on NO production or eNOS expression in intact HPAEC, suggesting that 1.0 μM of OA-NO2 does not represent the significant source of NO release. Vessel relaxation studies are in apparent contradiction to the observation that NO2-FA-derived release of NO in aqueous media (following Nef-like acid-base chemistry) is inhibited by intercalation in micelles and liposomes, leading to NO release of little or no biological significance [22, 26]. Additionally, NO2-FAs were shown to mediate elevation of NO levels rather via activation of different signaling molecules (e.g. protein kinase B and extracellular signal regulated kinases 1/2) in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) and coronary aortic and bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAEC) [12, 23]. Based on these facts and presented data we suppose that the OA-NO2-mediated upregulation of hypoxia- and ADMA-decreased NO production is not a consequence of direct release of NO from OA-NO2, but is dependent on activation/inhibition of signaling pathways described in more details below.

(2) In the following experiments we discovered that OA-NO2 inhibits hypoxia- and ADMA-induced production of IL-6 and expression of ICAM-1, which confirmed the anti-inflammatory potential of NO2-FAs in the development of PH phenotype in HPAEC. As mentioned above, pro-inflammatory mediators such as cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules play an important role in the development of endothelial dysfunction and pathogenesis of PH induced by different kinds of stimuli (e.g. hypoxia and ADMA) (reviewed in [2]). In our study, the exposure of hypoxia- and ADMA-treated HPAEC to OA-NO2 was associated with prevention of IL-6 production and ICAM-1 expression in these cells. ADMA- and OA-NO2-induced changes in ICAM-1 expression corresponded with the ability of neutrophils to adhere to HPAEC. These results confirmed previous observations where the inhibitory effect of NO2-FAs (nitro-linoleic acid, L-NO2 and OA-NO2) on IL-6 and ICAM-1 was also described by several authors in different in vitro and in vivo models [11, 14, 27, 28–30]. These findings were supported by functional assays demonstrating OA-NO2 ability to reduce ADMA-induced migration activity of HPAEC.

(3) Importantly, we are the first to report that OA-NO2 blocks the phosphorylation of STAT3 within tens of minutes after HPAEC exposition to hypoxia or ADMA. STAT3 is a cytoplasmic transcription factor, activated in response to different kinds of stimuli (e.g. hypoxia, ADMA, and IL-6) (reviewed in [18]), which regulate diverse cellular processes including growth, survival, and inflammation [17, 18]. Recently, several downstream STAT3 targets, associated with PH manifestation, have also been identified [2, 17, 18]. STAT3 was shown to be required for increased HIF-1α expression in response to hypoxia, which consequently leads to expression of genes responsible for regulation of critical cellular functions (reviewed in [31]). Likewise, ADMA was also shown to induce stabilization of HIF-1α in a STAT3-dependent manner [9]. These results show that inhibition of STAT3 phosphorylation by OA-NO2 (1.0 μM) is associated with prevention of HIF-1α stabilization in HPAEC treated with either hypoxia or ADMA. In contrast to our results, Rudincki et al. [32] demonstrated that NO2-FAs (L-NO2 and OA-NO2, final concentration 10.0 μM) are able to upregulate protein expression of HIF-1α and HIF-1α targeted genes, leading to increased migration and development of pro-angiogenic phenotype in HUVEC. Interestingly, Wu et al. [30], also showed that OA-NO2 (2.5 μM) increases HIF-1α protein expression via activation of heme oxygenase-1 pathway in BAEC. The authors suggest that this signaling pathway might play an essential role in compensating or protecting vascular endothelial function against vascular injury [30]. We hypothesize that these inconsistent results are a consequence of distinct concentration of NO2-FAs (1.0 μM vs. 2.5–10.0 μM) used in experiments as well as with different cellular models investigated (HPAEC vs. HUVEC and BAEC). Nevertheless, in our model OA-NO2-dependent inhibition of HIF-1α stabilization was accompanied with prevention of endothelial dysfunction in HPAEC, described in previous sections. Importantly, our results supply and strongly support our previous study, where OA-NO2 was shown to prevent development of hypoxia-induced PH [16]. In that study, OA-NO2 significantly attenuated hypoxia-induced right ventricular hypertrophy and fibrosis in mice as well as activation of macrophages and smooth muscle cells in vitro [16]. STAT3 has also been implicated in the inhibition of eNOS expression and NO production by increased binding of STAT3 on the eNOS promoter [33]. These facts are consistent with data presented in our study, where hypoxia- and ADMA-induced activation of STAT3 correlates with reduced bioavailability of NO and expression of eNOS. A similar mechanism has been described for STAT3-dependent regulation of cytokine production (e.g. IL-6 and IL-10), ICAM-1 expression, and migration induced in vascular ECs [17].

In conclusion, we suggest that OA-NO2-mediated inhibition of STAT3 is the primary mechanism of how this compound supports NO production and eNOS expression and blocks IL-6 production and ICAM-1 expression in HPAEC influenced by hypoxia or ADMA. However, we cannot exclude the involvement of other signaling pathways in later phases of endothelial dysfunction (e.g. NF-κB, MAPKs, Keap1/Nrf2 system, and PPAR-γ). Importantly, our results imply that NO2-FAs might significantly alter the development of endothelial dysfunction and inflammatory processes in the lungs.

Clinical Relevance

Development of pulmonary hypertension (PH) significantly increases the morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic lung diseases. Only few clinical therapies exist for the treatment of PH and prevention strategies remain largely unknown. Our study is bringing a new perspective on the molecular mechanism of nitro-fatty acid (NO2-FAs) action in hypoxia- and asymmetric dimethylarginine-induced pulmonary endothelial dysfunction, representing a causal link in the progression of PH. Nitro-oleic acid blocks upregulation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3/hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha signaling cascade, which results in prevention of the PH phenotype in human pulmonary endothelial cells. We suggest that NO2-FAs represent potential pharmaceuticals that could be used for future clinical interventions in PH.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jirina Prochazkova, Lenka Svihalkova Sindlerova, and Ondrej Vasicek for a fruitful discussion and insightful suggestions.

Funding This work was supported by the Czech Science Foundation (no. 13-40824P), the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports (no. LD15069). LK and MP were supported by the European Regional Development Fund, the projects NPS II no. LQ1605 and FNUSA-ICRC no. CZ.1.05/1.1.00/02.0123 from MEYS CR. BAF was supported by NIH grants R01-HL-058115, R01-HL-64937, and PO1-HL-103455.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest Bruce A. Freeman (BAF) and Steven R. Woodcock (SRW) acknowledge an interest in Complexa, Inc., as scientific founder/shareholder (BAF) and consultant (SRW). All other authors declare no conflicts of interest with respect to the contents of this manuscript.

Ethical Approval This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10557-016-6700-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Sitbon O, Lascoux-Combe C, Delfraissy JF, et al. Prevalence of HIV-related pulmonary arterial hypertension in the current antiretroviral therapy era. Am J Resp Crit Care. 2008;177:108–13. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200704-541OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schermuly RT, Ghofrani HA, Wilkins MR, Grimminger F. Mechanisms of disease: pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8:443–55. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fonseca GH, Souza R, Salemi VM, Jardim CV, Gualandro SF. Pulmonary hypertension diagnosed by right heart catheterization in sickle cell disease. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:112–8. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00134410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanli C, Oguz D, Olgunturk R, et al. Elevated homocysteine and asymmetric dimethyl arginine levels in pulmonary hypertension associated with congenital heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 2012;33:1323–31. doi: 10.1007/s00246-012-0321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lüneburg N, Harbaum L, Hennigs JK. The endothelial ADMA/NO pathway in hypoxia-related chronic respiratory diseases. Biomed Res Int. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/501612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parikh RV, Scherzer R, Nitta EM, et al. Increased levels of asymmetric dimethylarginine are associated with pulmonary arterial hypertension in HIV infection. AIDS. 2014;28:511–9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trittmann JK, Peterson E, Rogers LK, et al. Plasma asymmetric dimethylarginine levels are increased in neonates with bronchopulmonary dysplasia-associated pulmonary hypertension. J Pediatr. 2015;166:230–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iannone L, Zhao L, Dubois O, et al. miR-21/DDAH1 pathway regulates pulmonary vascular responses to hypoxia. Biochem J. 2014;462:103–12. doi: 10.1042/BJ20140486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pekarova M, Koudelka A, Kolarova H, et al. Asymmetric dimethyl arginine induces pulmonary vascular dysfunction via activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 and stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha. Vasc Pharmacol. 2015;73:138–48. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rudolph TK, Rudolph V, Edreira MM, et al. Nitro-fatty acids reduce atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscl Throm Vas. 2010;30:938–45. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.201582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rudolph V, Rudolph TK, Schopfer FJ, et al. Endogenous generation and protective effects of nitro-fatty acids in a murine model of focal cardiac ischaemia and reperfusion. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;85:155–66. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khoo NK, Rudolph V, Cole MP, et al. Activation of vascular endothelial nitric oxide synthase and heme oxygenase-1 expression by electrophilic nitro-fatty acids. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:230–9. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang J, Villacorta L, Chang L, et al. Nitro-oleic acid inhibits angiotensin II–induced hypertension. Circ Res. 2010;107:540–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.218404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kansanen E, Jyrkkänen HK, Volger OL, et al. Nrf2-dependent and -independent responses to nitro-fatty acids in human endothelial cells: identification of heat shock response as the major pathway activated by nitro-oleic acid. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:33233–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.064873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schopfer FJ, Cole MP, Groeger AL, et al. Covalent peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor{gamma} binding by nitro-fatty acids: endogenous ligands act as selective modulators. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:12321–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.091512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klinke A, Möller A, Pekarova M, et al. Protective effects of 10-nitro-oleic acid in a hypoxia-induced murine model of pulmonary hypertension. Am J Resp Cell Mol. 2014;51:155–62. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0063OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang XP, Irani K, Mattagajasingh S, et al. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3alpha and specificity protein 1 interact to upregulate intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in ischemic-reperfused myocardium and vascular endothelium. Arterioscl Throm Vasc. 2005;25:1395–400. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000168428.96177.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paulin R, Meloche J, Bonnet S. STAT3 signaling in pulmonary arterial hypertension. JAK-STAT. 2012;1:223–33. doi: 10.4161/jkst.22366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun CK, Zhen YY, Lu HI, Sung PH, et al. Reducing TRPC1 expression through liposome-mediated siRNA delivery markedly attenuates hypoxia-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension in a murine model. Stem Cells Int. 2014;2014:316214. doi: 10.1155/2014/316214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ambrozova G, Martiskova H, Koudelka A, et al. Nitro-oleic acid modulates classical and regulatory activation of macrophages and their involvement in pro-fibrotic responses. Free radical bio med. 2016;90:252–60. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lim DG, Sweeney S, Bloodsworth a, et al. Nitrolinoleate, a nitric oxide-derived mediator of cell function: synthesis, characterization, and vasomotor activity. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15941–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232409599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lima ES, Bonini MG, Augusto O, Barbeiro HV, Souza HP, Abdalla DS. Nitrated lipids decompose to nitric oxide and lipid radicals and cause vasorelaxation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39:532–9. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freeman BA, Baker PR, Schopfer FJ, Woodcock SR, Napolitano A, d’Ischia M. Nitro-fatty acid formation and signaling. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15515–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800004200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shin E, Yeo E, Lim J, et al. Nitrooleate mediates nitric oxide synthase activation in endothelial cells. Lipids. 2014;49:457–66. doi: 10.1007/s11745-014-3893-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang H, Jia Z, Sun J, et al. Nitrooleic acid protects against cisplatin nephropathy: role of COX-2/mPGES-1/PGE2 cascade. Mediat Inflamm. 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/293474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balazy M, Iesaki T, Park JL, et al. Vicinal nitrohydroxyeicosatrienoic acids: vasodilator lipids formed by reaction of nitrogen dioxide with arachidonic acid. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;299:611–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schopfer FJ, Baker PR, Giles G, et al. Fatty acid transduction of nitric oxide signaling. Nitrolinoleic acid is a hydrophobically stabilized nitric oxide donor. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19289–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414689200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ambrozova G, Fidlerova T, Verescakova H, et al. Nitro-oleic acid inhibits vascular endothelial inflammatory responses and the endothelial-mesenchymal transition. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.07.010. pii: S0304–4165(16)30251–30253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reddy AT, Lakshmi SP, Dornadula S, Pinni S, Rampa DR, Reddy RC. The nitrated fatty acid 10-nitro-oleate attenuates allergic airway disease. J Immunol. 2013;191:2053–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Villacorta L, Chang L, Salvatore SR, et al. Electrophilic nitro-fatty acids inhibit vascular inflammation by disrupting LPS-dependent TLR4 signalling in lipid rafts. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;98:116–24. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu Y, Dong Y, Song P, Zou MH. Activation of the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) by nitrated lipids in endothelial cells. PLoS One. 2012 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 31.Stenmark KR, Fagan KA, Frid MG. Hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Circ Res. 2006;99:675–91. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000243584.45145.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rudnicki M, Faine LA, Dehne N, et al. Hypoxia inducible factor-dependent regulation of angiogenesis by nitro-fatty acids. Arterioscl Throm Vasc. 2011;31:1360–7. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.224626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saura M, Zaragoza C, Bao C, Herranz B, Rodriguez-Puyol M, Lowenstein CJ. Stat3 mediates interleukin-6 [correction of interelukin-6] inhibition of human endothelial nitric-oxide synthase expression. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30057–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606279200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.