Abstract

We studied the properties of GABAA receptors microtransplanted from the human temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE)-associated brain regions to Xenopus oocytes. Cell membranes, isolated from surgically resected brain specimens of drug-resistant TLE patients, were injected into frog oocytes, which rapidly incorporated human GABAA receptors, and any associated proteins, into their surface membrane. The receptors originating from different epileptic brain regions had a similar run-down but an affinity for GABA that was ≈60% lower for the subiculum receptors than for receptors issuing from the hippocampus proper or the temporal lobe neocortex. Moreover, GABA currents recorded in oocytes injected with membranes from the subiculum had a more depolarized reversal potential compared with the hippocampus proper or neocortex of the same patients. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed of the GABAA receptor α1- to α5-, β1- to β3-, γ2- to γ3-, and δ-subunit mRNAs. The levels of expression of the α3-, α5-, and β1- to β3- subunit mRNAs are significantly higher, with the exception of γ2-subunit whose expression is lower, in subiculum compared with neocortex specimens. Our results suggest that an abnormal GABA-receptor subunit transcription in the TLE subiculum leads to the expression of GABAA receptors with a relatively low affinity. This abnormal behavior of the subiculum GABAA receptors may contribute to epileptogenesis.

Keywords: temporal lobe epilepsy

The principal brain regions generating partial seizures in humans afflicted by intractable, cryptogenic temporal lobe (TL) epilepsy (TLE) include the hippocampus and the temporal neocortex. However, their role in epileptogenesis remains an open question (1, 2), and the functional and anatomical correlates of TLE are areas of lively debate (3–5). To address these issues, we recently introduced the method of microtransplanting already assembled neurotransmitter receptors from the human epileptic brain to the plasma membrane of Xenopus oocytes (6–8), and we have shown that GABAA receptors, transplanted from TL epileptic brains into oocytes, display an excessive GABAA-receptor run-down, which is very similar to that of GABA currents recorded from pyramidal neurons in TL slices derived from the same patients (9, 10).

In this article, we compare the functional properties and the subunit composition of human GABAA receptors expressed across some epileptic regions. Particular attention has been placed on investigating the properties of receptors from the epileptic subiculum, where TLE-associated functional alterations of neuronal GABA responses have been described (11). We report relevant differences compared with other epileptic areas.

Materials and Methods

Patients. Surgical specimens were obtained from the hippocampus and temporal neocortex of six patients with cryptogenic drug-resistant TLE (see Table 2, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site); all operations were performed at the Neuromed Neurosurgery Center for Epilepsy (Venafro, Italy). Informed consent was obtained from all of the patients to use part of the biopsy material for our experiments, and the Ethics Committees of Neuromed and the University of Rome “La Sapienza” approved the selection processes and procedures. The histopathology of all specimens showed the typical neuropathological features of Ammon's horn sclerosis and did not show obvious sclerosis in the TL.

Membrane Preparation and Injection Procedures. Membranes were prepared as described (7, 8) by using tissues from human epileptic brain regions (hippocampus and TL).

Electrophysiology. At 12–48 h after injection, membrane currents were recorded from voltage-clamped oocytes by using two microelectrodes filled with 3 M KCl (12). The oocytes were placed in a recording chamber (volume, 0.1 ml) perfused continuously (9–10 ml/min) with oocyte Ringer's solution at room temperature (20–22°C). For some experiments, CaCl2 was pressure-injected into oocytes (13) from a pipette containing 50 mM CaCl2, and currents were elicited in response to ≈10 μM calcium. GABA current run-down was defined as the decrease (in percentage) of the current peak amplitude after six 10-s applications of GABA at 40-s intervals. The “GABA-current” (current elicited by GABA) desensitization was estimated as the time taken for the current to decay from its peak to half-peak value (T0.5). Dose–response curves were obtained as described in refs. 8 and 9 and Supporting Methods, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Quantitative RT-PCR Analysis. Expression levels of human GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs (α1- to α5-, β1- to β3-, γ2- to γ3-, and δ-subunits) were determined from resected human tissues of two TLE patients. Experiments were conducted as described in Supporting Methods.

Chemicals and Solutions. Oocyte Ringer's solution had the following composition: 82.5 mM NaCl/2.5 mM KCl/2.5 mM CaCl2/1 mM MgCl2/5 mM Hepes (adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH). All drugs were purchased from Sigma, unless indicated otherwise.

Results

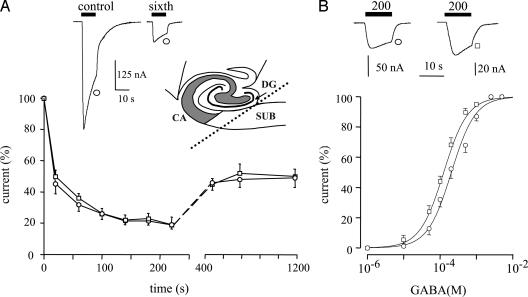

GABA Current Run-Down. Application of GABA (1 mM) to control (noninjected) oocytes did not elicit a significant current. In contrast, all of the oocytes injected with membranes from the subiculum elicited inward membrane currents. These currents were due to the activation of transplanted human GABAA receptors and were blocked by the competitive GABAA-receptor antagonist bicuculline (100 μM; data not shown). The GABA currents, elicited by the “epileptic receptors” (receptors transplanted from epileptic brains), desensitized with similar T0.5 values and exhibited also the same run-down for both the subiculum and the hippocampus proper (Fig. 1A; see Table 3, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Moreover, after the run-down, the GABA-current amplitudes recovered only partially, as shown (9) for epileptic receptors from the temporal cortex. Similar experiments, which were performed to investigate the GABA-currents from the hippocampus proper, showed that both the current decay and the current run-down were very similar to those of the TL neocortex. Therefore, the excessive run-down of GABA-currents discovered previously in the epileptic TL, is a property that is shared by GABAA receptors from all of the epileptic brain regions examined (see Table 3).

Fig. 1.

GABAA currents generated by receptors microtransplanted from the hippocampus and subiculum of a TLE patient (patient 4 in Table 2) to Xenopus oocytes. Symbols identify the tissue source of the membranes. (A) (Upper) Sample currents to the first and sixth GABA applications (1 mM, 10 s) from a membrane-injected oocyte. (Inset) Schematic representation showing the location of the subiculum (SUB), dentate gyrus (DG), and cornu ammonis (CA) hippocampal regions. (Lower) Time-course of current run-down during repetitive applications of GABA. Note the similar run-down in subiculum (○) vs. hippocampus proper (□) from the same patient. Points represent mean current amplitudes (±SEM) from six to eight oocytes (three frogs) normalized to Imax = -204 ± 29 nA (○) and -162 ± 29 nA (□). (B)(Upper) Sample currents elicited by the indicated GABA concentrations (μM) from the experiments shown below. (Lower) Dose–response relations from membrane-injected oocytes as indicated. Data are for the same patient as in A. Currents are normalized to Imax = -196 ± 14 nA (○) and -186 ± 32 nA (□) from 8–12 oocytes (six frogs). Note the shift to the right of the GABA dose–response curve for the human TLE subiculum (○) compared with the TLE hippocampus proper (□). Fitting parameters are given in Table 1.

Apparent Affinity of GABAA Receptors. To define the characteristics of the subiculum GABAA receptors in more detail, GABA dose–current response relations were obtained for receptors originating from different epileptic brain regions (e.g., Fig. 1B). The membrane currents elicited by different concentrations of GABA in oocytes injected with subicular membranes from five patients yielded GABA dose–current relations with essentially similar mean EC50 values (Table 1). Moreover, these mean values were significantly higher than those of oocytes injected with membranes isolated from hippocampus proper and TL of the TLE patients examined (Table 1 and Fig. 1B; same batches of oocytes). Interestingly, the subicular EC50 values were much higher than EC50 values reported in epileptic brain by us and in other cell systems by other researchers (ref. 10 and references therein). Together, our findings yield the following sequence of epileptic GABAA-receptor apparent affinity in the TLE brain: subiculum < hippocampus proper = neocortex.

Table 1. GABAA-receptor properties in TLE brain regions.

| Patient | Anatomy | EC50, μM | nH | Zn2+ IC50, μM | nH | EGABA, mV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sub | 207 ± 17* (12) | 1.2 | 1,110 ± 52* (9) | 0.9 | -13 ± 1.4* (15) |

| Hipp | 124 ± 9 (10) | 1.0 | 417 ± 20 (6) | 0.9 | -22 ± 1.5 (12) | |

| TL | 120 ± 7 (8) | 1.3 | ND | ND | -23 ± 2.0 (5) | |

| 2 | Sub | 196 ± 9* (10) | 1.1 | 527 ± 30 (9) | 2.1 | -25 ± 1.0 (16) |

| Hipp | 114 ± 5 (10) | 1.4 | 433 ± 34 (6) | 1.2 | -24 ± 3.0 (14) | |

| TL | 116 ± 8 (8) | 1.3 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 3 | Sub | 211 ± 14* (6) | 2.0 | 1,166 ± 33* (6) | 1.5 | -15 ± 0.5* (7) |

| Hipp | 152 ± 12 (6) | 2.0 | 662 ± 43 (6) | 0.9 | -24 ± 0.7 (7) | |

| 4 | Hipp | 126 ± 14 (6) | 1.3 | ND | ND | -26 ± 0.3 (6) |

| TL | 115 ± 15 (6) | 1.1 | 434 ± 22 (7) | 1.1 | -23 ± 0.5 (8) | |

| 5 | Sub | 200 ± 7* (10) | 1.1 | 500 ± 7 (6) | 2.0 | -18 ± 1.2* (12) |

| TL | 113 ± 4 (6) | 1.0 | 492 ± 48 (6) | 1.0 | -23 ± 0.6 (6) | |

| 6 | Sub | 233 ± 30* (7) | 1.1 | 500 ± 36 (6) | 1.1 | -16 ± 0.3* (8) |

| TL | 101 ± 13 (6) | 1.0 | 498 ± 40 (6) | 1.1 | -24 ± 0.5 (6) |

The number of oocytes is given in parentheses throughout. Data are means ± SEM from two to nine frogs. Sub, subiculum; Hipp, hippocampus proper; TL, temporal lobe; ND, not determined.

Significantly different (P < 0.001) compared with all others

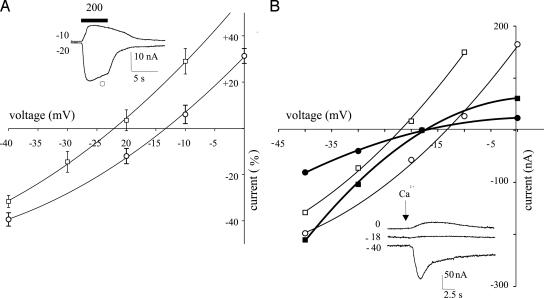

Reversal Potential of GABA Currents (EGABA). The GABA currents from oocytes injected with subicular membranes decreased in amplitude as the oocytes were depolarized and, in four of five tested patients, the current inverted direction on average at -15.5 ± 1.4 mV (e.g., Fig. 2A and Table 1). Interestingly, EGABA was significantly different (P < 0.01) from that of oocytes injected with membranes from the hippocampus proper or TL of the same patients (-24.1 ± 1.5 mV, Fig. 2 A and Table 1). Moreover, the latter experiments were performed by using the same batches of oocytes and alternating the recordings between hippocampus proper-, TL-, and subiculum-injected oocytes. To determine whether the difference in EGABA was due to an altered Cl- gradient across the oocyte membrane, we measured the chloride reversal potential (ECl) of the native Ca2+ activated Cl- channels (14) by injecting Ca2+ ions directly into the oocytes (13). The ECl was found to be the same in oocytes injected with membranes from the subiculum (-18.3 ± 1.6; eight cells/two frogs; Fig. 2B), hippocampus proper (-18.5 ± 2.2; nine cells/two frogs) or in noninjected oocytes (-19.2 ± 1.1; eight cells/two frogs) (13, 14), indicating that the differences in the EGABA reported here are not due to changes in the Cl- membrane gradient of the oocyte. Thus, it appears that the EGABA from oocytes injected with subicular membranes is depolarized significantly compared with the ECl and EGABA values obtained from the other examined epileptic regions (i.e., hippocampus proper and TL; see Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Current–voltage relations from oocytes injected with membranes from the brain of a patient (patient 1 in Table 2). (A) Points represent means ± SEM of peak GABA currents normalized to Imax (at -80 mV membrane holding potential) = -61.5 ± 9 nA (□; TLE hippocampus proper) and -79.6 ± 8 nA (○; TLE subiculum). Currents are inverted at -22 mV (□) and -13 mV (○). The GABA concentration was 200 μM (12 oocytes/four frogs). (Inset) Sample currents from the same experiments at the indicated holding potentials (in mV). The horizontal bar indicates GABA application at the indicated concentration (in μM). (B) Membrane currents elicited by injections of Ca2+ into two oocytes injected with subiculum (•) or hippocampus proper membranes (▪), both inverting at -18 mV; and GABA currents from the same oocytes. In this case, (○) refers to the subiculum and (□) to the hippocampus proper, which inverted at -22 and -13.4 mV, respectively. (Inset) Sample Ca2+ currents from the same experiment.

Zinc-Mediated Inhibition of GABAA Receptors. It is known that Zn2+ is concentrated in the central nervous system and that it inhibits GABAA receptors by an allosteric mechanism that depends critically on the subunit composition of the receptor (15). Therefore, it was pertinent to study the inhibiting effects of Zn2+ on the epileptic GABAA receptors. It was found that the amplitude of the membrane current elicited by GABA (200 μM) decreased with the Zn2+ concentration. Furthermore, the Zn2+ dose–GABA-current response curves, fitted to a Hill equation, gave IC50 values that, in two of five examined patients, were higher for oocytes injected with membranes from the subicula than from the other regions (Table 1).

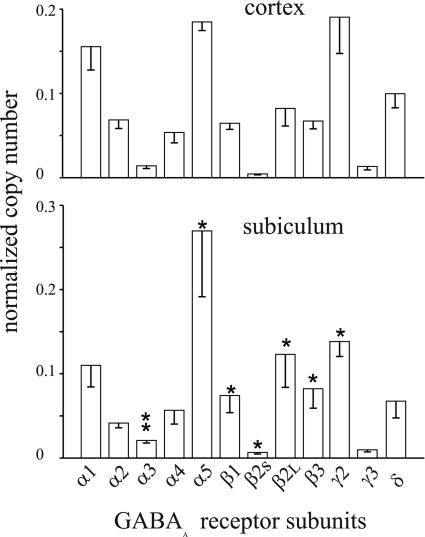

Quantitative RT-PCR Analysis. To determine whether the altered GABA affinity and zinc sensitivity in subiculum could depend on the receptor subunit composition, we analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR the expression of the α1- to α5-, β1-, β2S-, β2L-, β3-, γ2-, γ3, and δ-subunit mRNAs in the TLE subiculum vs. neocortex of two patients. It was found that the levels of mRNAs encoding some of the analyzed GABAA subunits were significantly different between neocortex and subiculum, as shown in Fig. 3. Specifically, the α3-, α5-, and β1- to β3-subunit mRNAs exhibited levels of expression significantly higher, whereas the expression of the γ2-subunit mRNA was significantly lower, in the subiculum compared with the neocortex. These differences may underlie the difference in GABA affinity. Notably, the zinc sensitivity was not altered in the two considered patients (i.e., patients 5 and 6).

Fig. 3.

Real-time quantitative analysis of the relative expression of GABAA subunit mRNAs from the cortex and subiculum of two TLE patients (patients 5 and 6). Each column represents the mean value obtained from six experiments per tissue (three experiments per patient). For each subunit, the relative mRNA copy number is normalized to the sum of the copy numbers of all examined subunits. Bars indicate SEM. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.001.

Discussion

An increasing variety of experimental approaches are being applied to investigate the pathogenesis of epilepsy by using human tissue resected during therapeutic surgery for epilepsy. Taking advantage of the brain tissues resected from six patients afflicted with TLE, we microtransplanted GABAA receptors from epileptic brain regions to Xenopus oocytes, and we report that the epileptic subicular GABAA receptors exhibit a reduced affinity for GABA, compared with GABAA receptors microtransplanted from the hippocampus proper and temporal neocortex of the same patients. Also, we report that the epileptic subicular GABA currents invert at more depolarized potentials than the currents generated by GABAA receptors from the other epileptic brain regions that we examined.

It is well known that the brain of TLE patients exhibit sclerosis with neuronal loss, especially in the hippocampus proper, and it could be thought that the GABAA-receptor properties that we describe are associated to gliosis in the hippocampal epileptic tissue. However, it has been recently shown (16) that the interictal activity in TLE is independent of the tissue sclerosis, and we find the same pattern of GABA responses through different brain regions, such as the neocortex and hippocampus proper. Thus, it seems that the differential behavior of the GABA responses throughout the epileptic nervous tissue cannot be attributed simply to nonhomogeneous nervous tissue.

Many recent studies aim at determining how GABA efficacy is altered in epileptic tissue (6, 17). This article work shows a reduced GABA affinity in the subiculum and confirms the reported (9) excessive run-down of the GABAA receptors throughout the epileptic tissues. This run-down would result in a diminished inhibitory action of GABA and, thus, could allow the development of seizures. Such a view is strongly supported by the fact that GABAA receptors display the lowest affinity for GABA in the subiculum, which is the origin of spontaneous field potential discharges that resemble those seen in the electroen-cephelogram of TLE patients (16).

Another factor that could contribute to the neurological disorders in TLE may be the EGABA, which was significantly depolarized in the subiculum compared with other examined brain regions. With this shift in equilibrium potential, GABA could become excitatory in the subicular nerve cells and, thus, play a role in epileptogenesis (11, 18–20). It is possible that the shift in EGABA of the injected oocytes is due to changes occurring only around the transplanted GABAA receptors because the overall ECl, measured by injecting calcium, was not altered. One possibility is that the local ECl is altered by dysfunctional Cl- transporters (11, 21) transplanted together with the epileptic GABA receptors.

It is known that the transition metal ion Zn2+ is released from mossy fiber nerve terminals of the hippocampus (22, 23) and inhibits GABAA receptors by an allosteric mechanism that depends on their subunit composition (15). Therefore, the reduced inhibitory efficacy of Zn2+, reported here in two patients, may favor excitability disorders in the subiculum and points to peculiar subunit compositions of GABAA receptors (15). This finding is in line with various facts. (i) Zn2+ efficacy is stringently related to GABAA-receptor subunit composition (15); (ii) GABAA-receptor subunit mRNA expression is altered in TLE models (5); and (iii) chronic benzodiazepine treatment, as that received in general by TLE patients, down-regulates GABAA-receptor subunits (24, 25). The reasons why epileptic GABAA receptors have a reduced sensitivity to GABA remain an open question. However, it may be true that the subicular receptors have an unusual subunit composition because the α3-, α5-, β1- to β3-, and γ2-subunits were found to be differentially expressed in epileptic TL neocortex vs. subiculum.

In conclusion, the epileptic brain has GABAA receptors endowed with abnormal properties, which impair inhibitory GABAergic transmission and, thus, can contribute to the increased susceptibility to seizures of human TLE, especially for the subicular area where many originate (11). Further studies on the molecular composition and on the mechanisms that regulate the function of these GABAA receptors in the original TLE tissues are essential to understand human epilepsies better and to develop more suitable treatments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients C.L., C.L.M., D.R.M., P.E., G.F., and D.V.C. (patients 1–6, respectively) for making this work possible. We also thank Drs. P. P. Quarato, G. Di Gennaro, F. Trettel, and S. Di Angelantonio for invaluable discussions. This work was supported by grants from Ministero della Salute (to F.E.), Ministero Università e Ricerca Fondo per gli Investimenti della Ricerca di Base (to F.E.), and Mexico's Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (to R.M. and A.M.-T.).

Abbreviations: TL, temporal lobe; TLE, TL epilepsy; EGABA, reversal potential of GABA currents; ECl, chloride reversal potential.

References

- 1.Kullmann, D. M. (2002) J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 73, Suppl. II, ii32-ii35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vadlamudi, L., Scheffer, I. E.& Berkovic, S. F. (2003) J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 74, 1359-1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bothwell, S., Meredith, G. E., Phillips, J., Staunton, H., Doherty, C., Grigorenko, E., Glazier, S., Deadwyler, S. A., O'Donovan, C. A. & Farrell, M. (2001) J. Neurosci. 21, 4789-4800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gibbs, J. W., III, Shumate, M. D. & Coulter, D. A. (1997) J. Neurophysiol. 77, 1924-1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loup, F., Weiser, H. G., Yonekawa, Y., Aguzzi, A. & Fritschy, J. M. (2000) J. Neurosci. 20, 5401-5419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marsal, J., Tigyi, G. & Miledi, R. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 5224-5228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miledi, R., Eusebi, F., Martinez-Torres, A., Palma, E. & Trettel, F. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 13238-13242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palma, E., Trettel, F., Fucile, S., Renzi, M., Miledi, R. & Eusebi F. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 2896-2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palma, E., Ragozzino, D. A., Di Angelantonio, S., Spinelli, G., Trettel, F., Martinez-Torres, A., Torchia, G., Arcella, A., Di Gennaro, G., Quarato, P. P., et al. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 10183-10188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palma, E., Esposito, V., Mileo, A. M., Di Gennaro, G., Quarato, P., Giangaspero, F., Scoppetta, C., Onorati, P., Trettel, F., Miledi, R. & Eusebi, F. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 15078-15083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen, I., Navarro, V., Clemenceau, S., Baulac, M. & Miles, R. (2002) Science 298, 1418-1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miledi, R. (1982) Proc. R. Soc. London Ser. B 215, 49l-497. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miledi, R. & Parker, I. (1984) J. Physiol. 357, 173-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kusano, K, Miledi, R. & Stinnakre, J. (1982) J. Physiol. 328, 143-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hosie, A. M., Dunne, E. L., Harvey, R. J. & Smart, T. G. (2003) Nat. Neurosci. 6, 362-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wozny, C., Kivi, A., Lehmann, T. N., Dehnicke, C., Heinemann, U. & Behr, J. (2003) Science 301, 463c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ben-Ari, Y. & Cossart, R. (2000) Trends Neurosci. 23, 580-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Köhling, R. (2002) Science 298, 1350-1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khalilov, I., Holmes, G. L. & Ben-Ari, Y. (2003) Nat. Neurosci. 6, 1079-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stein, V. & Nicoll, R. A. (2003) Neuron 37, 375-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stell, D. & Mody, I. (2004) Neuron 39, 729-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Assaf, S. Y. & Chung, S. H. (1984) Nature 308, 734-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coulter, D. A. (2000) Epilepsia 41, S96-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao, T. J. & Chiu, T. H. (1994) Mol. Pharmacol. 45, 657-663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown, M. J. & Bristow, D. R. (1996) Br. J. Pharmacol. 118, 1103-1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.