Abstract

Context:

Awareness under anesthesia is a rare but extremely unpleasant phenomenon. There are very few studies in the developing world and none from rural areas where incidence of intraoperative awareness may be higher due to increased patient load, limited patient knowledge and lack of trained hospital staff, reliance on older, cheaper but less effective drugs, and lack of proper equipment both for providing anesthesia, as well as monitoring the patient.

Aims:

To assess the incidence of intraoperative awareness during general anesthesia among patients in rural India and any factors associated with the same.

Settings and Design:

Prospective, nonrandomized, observational study.

Subjects and Methods:

Patients undergoing elective surgical procedures in various specialties under general anesthesia from over a period of 1 year were considered for this study. Approximately, after 1 h of arrival in postanaesthesia care unit, anesthesiologist (not involved in administering anesthesia) assessed intraoperative awareness using a modified form of Brice questionnaire.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Data were collected on a Microsoft Excel® sheet and analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences® version 23 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for windows.

Results:

A total of 896 patients completed the questionnaire. Postoperatively, in response to the questionnaire, seven patients reported to have remembered something under anesthesia. Out of these, three patients described events that were confirmed by operation theater staff to have occurred whereas they were under anesthesia.

Conclusions:

Incidence of definite awareness under anesthesia with postoperative recall was found to be 0.33% (three patients out of total 896) in our study.

Keywords: Anesthesia, awareness, rural patients

INTRODUCTION

Awareness during anesthesia has been defined as recall of intraoperative events by a patient operated under general anesthesia. It is a rare but extremely unpleasant phenomenon. From patient's point of view, intraoperative awareness under anesthesia is one of the most troublesome anesthesia-related complications, second only to postoperative nausea and vomiting.[1] Apart from intraoperative distress, it may result in the development of late postsurgical psychological disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder.[2,3] Moreover, awareness during intraoperative period has also become an important reason for anesthesia-related compensation claims. Intraoperative awareness is, therefore, described as the second most important complication anesthesiologists (after death)[4] as well. Various modalities have been tried to assess awareness in anesthetized patients. These include monitoring blood pressure, heart rate, end-tidal anesthetic concentration, and bispectral index (BIS). However, none of these modalities have been found to be 100% effective in detecting awareness under anesthesia.

Incidence of awareness in developed countries is found to be 0.1%–0.2%.[5,6] Although there are very few studies in the developing world, the incidence of intraoperative awareness is thought to be somewhat higher as compared to Western world.[7] This may in part be due to increased patient load, limited patient knowledge and lack of trained hospital staff, reliance on older, cheaper but less effective drugs, and lack of proper equipment both for providing anesthesia, as well as monitoring the patient. Problem can be even more complex and multifold in rural areas. However, even after a thorough review of literature, we could not find any study specifically estimating the problem of awareness under anesthesia in rural areas. Therefore, we conducted this prospective, nonrandomized, observational study to assess the incidence of intraoperative awareness during general anesthesia among patients in rural India and any factors associated with or influencing the same.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

This prospective, single-center, nonrandomized, observational study was performed in a tertiary care hospital in rural India. Patients undergoing elective surgical procedures in various specialties (including general surgery, orthopedics, ear, nose and throat surgery, urosurgery, and plastic surgery) under general anesthesia from October 1, 2014, to September 30, 2015, i.e., over a period of 1 year were considered for this study. Inclusion criteria included patients aged 18 years or more, American Society of Anesthesiologist (ASA) Physical Status III or less, with normal neurological status. Patients who were aged <18 years, not extubated after surgery, and/or transferred to an Intensive Care Unit, or not mentally sound were excluded from this study. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients in their own language before including them in this study.

The technique and drugs used for anesthesia varied according to patient's preoperative condition, surgical procedure planned, and choice of anesthesiologist; however, all patients considered for this study underwent general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation and positive pressure ventilation. Induction agent used was either thiopentone sodium or propofol given intravenously followed by muscle relaxant which was either vecuronium or atracurium. After intubation maintenance of anesthesia was done using 50% oxygen, 50% nitrous oxide, and volatile anesthetic (isoflurane or sevoflurane). During the procedure and throughout the postoperative period, vital signs (including heart rate, oxygen saturation, electrocardiography, and noninvasive blood pressure) of the patients were monitored. Concentration of volatile anesthetic was adjusted according to patient's vital signs, as well as clinical parameters such as pupillary response, sweating, and tearing. Instrumental monitoring of cerebral electrical activity and volatile anesthetic concentration was not carried out, as the same was not available in our institute. None of the patients included in this study underwent surgical procedure under mask ventilation or laryngeal mask airway insertion. Furthermore, total intravenous anesthesia was not used in any patient. A consultant anesthesiologist (with sufficient experience of general anesthesia) who was unaware about the patients being included in this study anesthetized all patients. Noise levels in operation theater were kept to a minimum, with only minor chat surgeons, anesthesiologist, and operation theater staff. After the completion of surgical procedure, anesthesia was reversed, extubated, and shifted to postanesthesia care unit (PACU) after adequate return of consciousness.

Approximately after 1 h of arrival in PACU, anesthesiologist (not involved in administering anesthesia) assessed intraoperative awareness. Anesthesiologist visited the patient and asked questions in his/her own language. First general information such as age, sex, ASA status, anesthesia technique used, history of chronic drug intake or substance abuse, and any previous history of awareness was obtained. The second part of the questionnaire was a modified form of Brice questionnaire,[8] used by similar studies designed to assess intraoperative awareness,[5,6,7,9] in the past.

What is the last thing you remember before going to sleep?

What is the first thing you remember after waking up?

Do you remember anything between going to sleep and waking up?

Did you dream during your procedure?

What was the worst thing about your operation?

After the questionnaire was completed, it was analyzed, and patients were categorized into either having definite awareness, possible awareness, and no awareness. If the event recalled was confirmed by attending personnel present in operation theater, or investigators were convinced that memory was real, patients were categorized under definite awareness. If the patient was unable to recall any event definitely indicative of awareness, but memories could have been related to intraoperative events, he/she was categorized as possible awareness. No awareness was defined as a patient with no reported awareness or if the recalled events had a high probability of occurring in immediate pre- or post-operative period. This classification is similar to one used in various other studies assessing intraoperative awareness.[5,9,10,11] Patients having intraoperative dreaming were categorized separately.[5,11,12]

Patients having awareness or possible awareness were offered to follow up in anesthesia outpatient department.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected on a Microsoft Excel® sheet and analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences® version 23 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for windows. Data were expressed as ratio and proportion. Correlational studies were performed by Fisher's extract test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

From October 1, 2014, to September 30, 2015, a total of 1068 adult patients underwent elective surgical procedures under general anesthesia. Out of these, 37 patients were ASA Grade IV, so were excluded from the study, 121 patients refused to take part in the study. Of the remaining, 12 had to be shifted to Intensive Care Unit intubated and 2 were disoriented so were thus excluded from the study. There was no disruption of anesthesia or circuit failure in any case. Hence, a total of 896 patients completed the questionnaire.

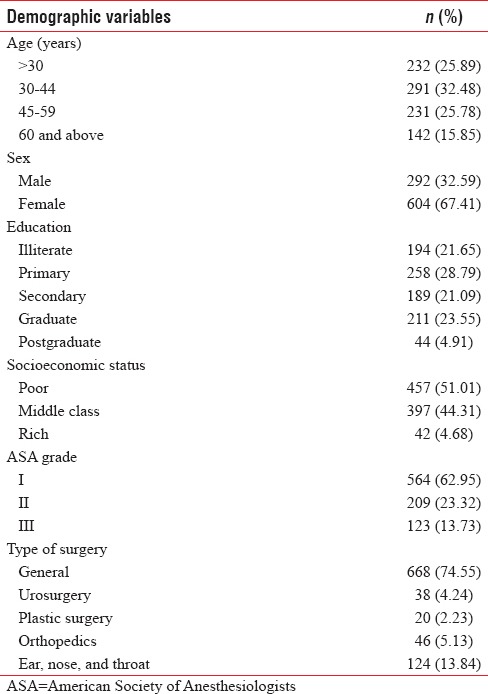

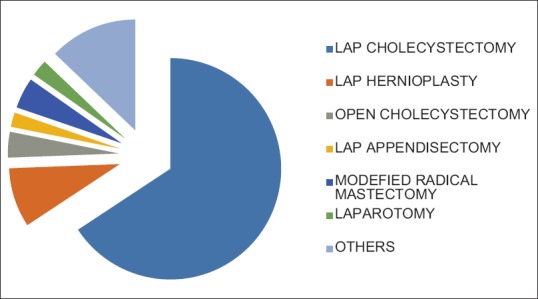

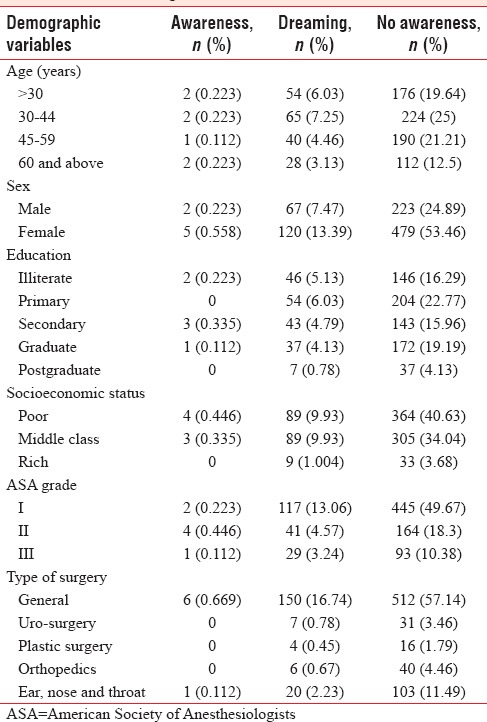

Of these 896 patients, 25.89% [Table 1] of patients were <30 years of age, 32.48% were between 30 and 44 years, 25.78% were between 45 and 59 years, and remaining 15.85% were 60 years and above. Nearly 32.59% of participants were males and the rest were females [Table 1]. As far as education level was concerned, 194 (21.65%) patients were illiterate, 258 (28.79%) patients studied up to primary standard, 189 (21.09%) patients till secondary level, 211 (23.55%) were graduates, and remaining 44 (4.91%) were postgraduates [Table 1]. Based on socioeconomic status, roughly half of the patients were poor (51.01%), 44.31% belonged to middle class, and 42 (4.61%) patients were rich. According to ASA grading, 62.95% of patients were ASA Grade I, 23.32% were ASA Grade II, and 13.73% were ASA Grade III [Table 1]. All the patients underwent elective surgical procedures under general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation using muscle relaxants. A maximum number of patients participating in the present study underwent general surgical procedures (77.01%), followed by ear, nose, and throat surgery (11.38%), orthopedic surgery (5.13%), urosurgery (4.24%), and plastic surgery (2.23%) [Table 1]. Among the patients undergoing general surgical procedures, 439 patients (65.72%) underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy, 58 (8.68%) underwent laparoscopic hernioplasty, 14 (2.09%) laparoscopic appendectomy, 25 (3.74%) open cholecystectomy, 30 (4.49%) modified radical mastectomy, 16 (2.39%) laparotomy, and remaining 86 patients (12.87%) had various other elective surgical procedures [Figure 1].

Table 1.

Demographic variables of patients included in the study

Figure 1.

Type of general surgical procedures performed on patients participating in the study

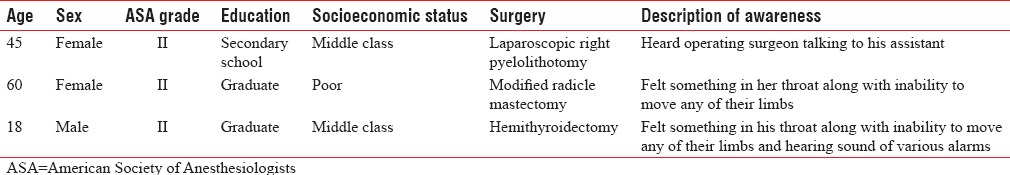

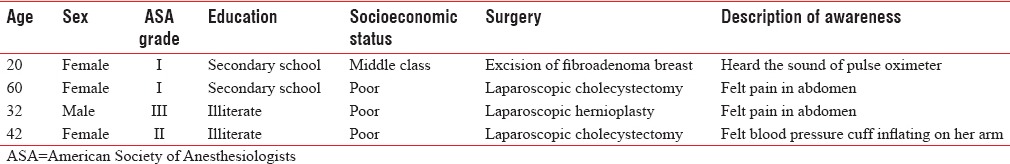

Postoperatively, in response to the questionnaire, seven patients reported to have remembered something under anesthesia, i.e., yes to question number 3. Out of these, three patients [Table 2] described events that could be classified as awareness under anesthesia. One patient heard operating surgeon talking to his assistant, and the conversation described, was later confirmed by the surgeon to be almost accurate. Two other patients felt something in their throat while under anesthesia along with the inability to move any of their limbs. One of them also described hearing sound of various alarms in operation theater. Remaining four patients [Table 3] described vague events or sounds not likely to have occurred inside the operating room or may have happened in immediate postoperative period. Two of these patients experienced abdominal pain under anesthesia, one heard the sound of pulse-oximeter, and other one felt blood pressure cuff inflating on his arm while under anesthesia. Hence, in a total three patients, out of total 896 patients operated under general anesthesia were found to have awareness in our study, and incidence was calculated to be 0.33% in our study.

Table 2.

Patients with definite awareness under anesthesia

Table 3.

Patients with possible awareness under anesthesia

Apart from above findings, 187 (20.87%) patients reported various dreams under anesthesia. None of the patients having definite awareness reported intraoperative dreaming under anesthesia; however, two patients with possible awareness reported intraoperative dreaming. Hence, the incidence of awareness (definite and possible) in patients with intraoperative dreaming was found to be 1.069% in our study which was slightly higher than in patients reporting no intraoperative dreams, i.e., 0.705%. However, on applying Fisher's extract test, P value comes out to be 0.6405. Hence, no significant association was noted among patients having intraoperative awareness and dreaming under anesthesia.

Distribution of patients with awareness, dreams, and no awareness into various demographic categories is given in Table 4. To analyze the effect of various variables such as age, sex, education, socioeconomic status, ASA grade, and type of surgery on incidence of awareness under anesthesia, we pooled patients with definite and possible awareness together and compared them with patients having no awareness. No statistically significant impact of any variable was noted on intraoperative awareness and intraoperative dreaming in the present study.

Table 4.

Demographic characteristics of patients with awareness, dreaming, and no awareness under anesthesia

DISCUSSION

Incidence of awareness under anesthesia with postoperative recall was found to be 0.33% in our study. However, if patients with possible awareness were also included, incidence of awareness under anesthesia would become 0.78%. This occurrence is higher than reported by most studies conducted in the Western world which estimated the incidence to be between 0.1% and 0.2%.[5,6] However, in a study by Errando et al.[13] done on over 4000 patients, incidence of awareness with recall was found to be 1.0% among all patients operated under anesthesia and 0.8% after removing high-risk cases.

Although most of such studies have been conducted in the Western world, one study from China[7] conducted by Xu et al., involving 11,101 patients had calculated the incidence of intraoperative awareness to be 0.41%, which was higher than that reported in the Western world. Incidence of intraoperative dreaming in the same study was found to be 3.19%. Another study done in Japan[14] reported an incidence as low as 0.028% including patients reporting possible awareness, with most of the cases reportedly conducted under total intravenous anesthesia (21 out of 24). One study conducted recently in a tertiary care hospital in India estimated incidence of awareness to be <1 in 300 (0.33%).[15] Hence, there is a variable but definite incidence of awareness in almost every hospital across the world. Such variation could be due to differences in anesthesia techniques and drugs used for proving anesthesia.

Another major initiative in this direction has been undertaken by Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland whose 5th National Audit Project reported accidental awareness during general anesthesia in the United Kingdom (UK).[16] According to it, incidence of awareness under anesthesia was estimated to be 1:15,414 in the UK, which was lower than reported in previous studies. Furthermore, almost half the cases of awareness in the UK were reported to have occurred after induction and before start of surgery. However, respondents in that project were anesthesiologists and not patients and cases that were brought to their knowledge only, were reported. Another study done in the UK[17] in 2004 had shown that anesthesiologist tends to underestimate awareness under anesthesia in their practice.

There could be multiple factors[18] responsible for awareness with recall under anesthesia and understanding them would be vital for planning preventive measures. One of the factors could be interindividual variability in anesthetic drug requirement. This could be due to genetic variations in expression and function of target receptors. Cheng et al.[19] in a study involving mice have found that genetic deficiency of alpha gamma-aminobutyric acid (5 GABA) leads to resistance to amnesic effects of anesthetic drug etomidate. Another study by Liang et al.[20] has shown that pharmacology of synaptic as well as extrasynaptic GABAA receptors in response to agonists and allosteric modulators is altered after long-term alcohol exposure. Thus, in addition to genetics, long-term exposure to certain substance or drugs may also play a role in altered response to anesthetics. Apart from variation in target receptors, patients presenting with compromised cardiac function or severe hypovolemia[18] may not be able to tolerate full anesthetic dose. In addition, alterations in heart rate and blood pressure in response to inadequate depth of anesthesia may be masked in patients using beta-blockers. Finally, abnormal function or poor maintenance of anesthesia equipment or lack of familiarity with new anesthesia equipment or technique may also lead to delivery of incorrect doses of anesthetic.[18]

Awareness under anesthesia, however, could be avoided if adequate depth of anesthesia is maintained during surgery. Monitoring by an experienced anesthesiologist using hemodynamic variables (such as heart rate, blood pressure), lacrimation, etc., has been done traditionally to maintain adequate depth of anesthesia. Although effective, awareness can still occur without any variation in vital parameters. Other techniques include estimation of volatile anesthetic gas concentration and minimum alveolar concentration in patients under anesthesia. Similarly, BIS monitoring has been used to maintain adequate depth of anesthesia. It measures specific electrical activity of brain with electrodes placed on patient's forehead and generates a numerical value which ranges from 0 to 100. A BIS value of 40–60 has been associated with low probability if awareness under anesthesia.

Studies have shown that a BIS value of >60 is usually associated with recovery from general anesthesia without recall.[21,22] A study by Myles et al.[10] had shown that use of BIS in high-risk patients reduces the incidence of awareness. Similarly, Ekman et al. had also found that the use of BIS-guided anesthesia reduces the incidence of awareness.[23] However, study done by Sebel et al.[5] did not find any statistically significant difference in terms of incidence of intraoperative awareness with recall in patients anesthetized under BIS guidance when compared to ones without it. Furthermore, an article titled “Practice Advisory for Intraoperative Awareness and Brain Function Monitoring” by ASA Task Force recommended that brain function monitoring is not routinely indicated in all patients undergoing surgery under general anesthesia.[24] It also endorsed a checklist protocol for anesthesia equipment to prevent awareness related to equipment malfunction resulting from inadequate delivery of anesthetic drugs. Other recommendations included the use of benzodiazepines and scopolamine in patients requiring lesser doses of anesthetic. However, it cautioned that use of benzodiazepine might lead to delayed emergence.[24]

In the light of above knowledge, a relatively higher incidence of awareness reported in our study could be due to various factors. First, the hospital where this study was done is located in an area with a relatively higher incidence of tobacco (mostly smoking) and alcohol abuse. Second, due to increased patient load, the time interval from diagnosis to surgery was up to 6 months in certain cases; patients awaiting surgery were usually kept on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for that period. Finally, no BIS monitoring or anesthetic gas concentration monitoring was available in our institute. Apart from this, other minor factors such as lack of routine checking protocol and/or periodic maintenance of anesthesia equipment due to rural location may also have played a role.

In spite of all precautions, our study had certain limitation. First, the patients were interviewed only once, i.e., after approximately 1 h after arrival in PACU. That may have resulted in missing of certain patients who might have experienced awareness under anesthesia. Second, none of the patients received in sedative or anxiolytic premedication. This might have resulted in reduced incidence of awareness. Hence, further studies with higher number of patients might be required to estimate the incidence of awareness under anesthesia in rural areas with further accuracy.

CONCLUSIONS

Finally, we conclude that the incidence of definite awareness under anesthesia with recall, in rural tertiary care hospital in India, was estimated to be 0.33%. We also concluded that intraoperative dreaming does not have any statistically significant association with awareness under anesthesia.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Macario A, Weinger M, Carney S, Kim A. Which clinical anesthesia outcomes are important to avoid? The perspective of patients. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:652–8. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199909000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leslie K, Chan MT, Myles PS, Forbes A, McCulloch TJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder in aware patients from the B-aware trial. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:823–8. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181b8b6ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samuelsson P, Brudin L, Sandin RH. Late psychological symptoms after awareness among consecutively included surgical patients. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:26–32. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200701000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macario A, Weinger M, Truong P, Lee M. Which clinical anesthesia outcomes are both common and important to avoid? The perspective of a panel of expert anesthesiologists. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:1085–91. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199905000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sebel PS, Bowdle TA, Ghoneim MM, Rampil IJ, Padilla RE, Gan TJ, et al. The incidence of awareness during anesthesia: A multicenter United States study. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:833–9. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000130261.90896.6C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandin RH, Enlund G, Samuelsson P, Lennmarken C. Awareness during anaesthesia: A prospective case study. Lancet. 2000;355:707–11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)11010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu L, Wu AS, Yue Y. The incidence of intra-operative awareness during general anesthesia in China: A multi-center observational study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:873–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.02016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brice DD, Hetherington RR, Utting JE. A simple study of awareness and dreaming during anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 1970;42:535–42. doi: 10.1093/bja/42.6.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avidan MS, Zhang L, Burnside BA, Finkel KJ, Searleman AC, Selvidge JA, et al. Anesthesia awareness and the bispectral index. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1097–108. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myles PS, Leslie K, McNeil J, Forbes A, Chan MT. Bispectral index monitoring to prevent awareness during anaesthesia: The B-Aware randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363:1757–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16300-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szostakiewicz KM, Tomaszewski D, Rybicki Z, Rychlik A. Intraoperative awareness during general anaesthesia: Results of the observational survey. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2014;46:23–8. doi: 10.5603/AIT.2014.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samuelsson P, Brudin L, Sandin RH. Intraoperative dreams reported after general anaesthesia are not early interpretations of delayed awareness. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2008;52:805–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Errando CL, Sigl JC, Robles M, Calabuig E, García J, Arocas F, et al. Awareness with recall during general anaesthesia: A prospective observational evaluation of 4001 patients. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:178–85. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morimoto Y, Nogami Y, Harada K, Tsubokawa T, Masui K. Awareness during anesthesia: The results of a questionnaire survey in Japan. J Anesth. 2011;25:72–7. doi: 10.1007/s00540-010-1050-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ambulkar RP, Agarwal V, Ranganathan P, Divatia JV. Awareness during general anesthesia: An Indian viewpoint. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2016;32:453–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.173363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pandit JJ, Cook TM, Jonker WR, O’Sullivan E. A national survey of anaesthetists (NAP5 baseline) to estimate an annual incidence of accidental awareness during general anaesthesia in the UK. Anaesthesia. 2014;68:343–53. doi: 10.1111/anae.12190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lau K, Matta B, Menon DK, Absalom AR. Attitudes of anaesthetists to awareness and depth of anaesthesia monitoring in the UK. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2006;23:921–30. doi: 10.1017/S0265021506000743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orser BA, Mazer CD, Baker AJ. Awareness during anesthesia. CMAJ. 2008;178:185–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng VY, Martin LJ, Elliott EM, Kim JH, Mount HT, Taverna FA, et al. Alpha5GABAA receptors mediate the amnestic but not sedative-hypnotic effects of the general anesthetic etomidate. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3713–20. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5024-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang J, Cagetti E, Olsen RW, Spigelman I. Altered pharmacology of synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAA receptors on CA1 hippocampal neurons is consistent with subunit changes in a model of alcohol withdrawal and dependence. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310:1234–45. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.067983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flaishon R, Windsor A, Sigl J, Sebel PS. Recovery of consciousness after thiopental or propofol. Bispectral index and isolated forearm technique. Anesthesiology. 1997;86:613–9. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199703000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glass PS, Bloom M, Kearse L, Rosow C, Sebel P, Manberg P. Bispectral analysis measures sedation and memory effects of propofol, midazolam, isoflurane, and alfentanil in healthy volunteers. Anesthesiology. 1997;86:836–47. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199704000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ekman A, Lindholm ML, Lennmarken C, Sandin R. Reduction in the incidence of awareness using BIS monitoring. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2004;48:20–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2004.00260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Intraoperative Awareness. Practice advisory for intraoperative awareness and brain function monitoring: A report by the American society of anesthesiologists task force on intraoperative awareness. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:847–64. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200604000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]