Abstract

Background:

It is unknown whether unstable chondral lesions observed during arthroscopic partial meniscectomy (APM) require treatment. We examined differences at 1 year with respect to knee pain and other outcomes between patients who had debridement (CL-Deb) and those who had observation (CL-noDeb) of unstable chondral lesions encountered during APM.

Methods:

Patients who were ≥30 years old and undergoing APM were randomized to receive debridement (CL-Deb group; n = 98) or observation (CL-noDeb; n = 92) of unstable Outerbridge grade-II, III, or IV chondral lesions. Outcomes were evaluated preoperatively and at 8 to 12 days, 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year postoperatively. Outcome measures included the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), visual analog scale (VAS) pain score, Short Form-36 (SF-36) health survey, range of motion, quadriceps circumference, and effusion. The primary outcome was the WOMAC pain score at 1 year. T tests were used to examine group differences in outcomes, and the means and standard deviations are reported.

Results:

There were no significant differences between the groups with respect to any of the 1-year outcome scores. Compared with the CL-Deb group, the CL-noDeb group had improvement in the KOOS quality-of-life (p = 0.04) and SF-36 physical functioning scores (p = 0.01) as well as increased quadriceps circumference at 8 to 12 days (p = 0.02); had improvement in the pain score on the WOMAC (p = 0.02) and KOOS (p = 0.04) at 6 weeks; had improvement in SF-36 physical functioning scores at 3 months (p = 0.01); and had increased quadriceps circumference at 6 months (p = 0.02).

Conclusions:

Outcomes for the CL-Deb and CL-noDeb groups did not differ at 1 year postoperatively. This suggests that there is no benefit to arthroscopic debridement of unstable chondral lesions encountered during APM, and it is recommended that these lesions be left in situ.

Level of Evidence:

Therapeutic Level I. See Instructions for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Knee arthroscopy is extremely common (>900,000 patients per year in the U.S. alone), and several high-quality clinical trials have helped to define its indications in certain conditions1-5. Arthroscopic debridement for degenerative joint disease has not been shown to be beneficial, and initial nonoperative management is also recommended for degenerative meniscal tears1-4,6-8. Current indications for arthroscopic partial meniscectomy (APM) are symptomatic meniscal tears that have failed nonoperative management after at least 3 months, particularly when there are no associated radiographic signs of degenerative joint disease7. It has also been shown that the best results of APM are obtained in patients without coexisting chondral lesions6,9,10. Treatment is complicated by the fact that up to 61% of patients undergoing knee arthroscopy have been reported to have coexisting chondral degeneration that may not be evident on preoperative radiographs, and surgeons have no evidence regarding how to treat these lesions11. Standard treatment for unstable chondral lesions encountered during APM has been to debride the lesion(s)12. However, we know of no study comparing debridement of unstable chondral lesions with no debridement of such lesions in patients undergoing APM. Given the high prevalence of comorbid chondral lesions found during APM and the potential for progression of knee osteoarthritis, more research is needed to determine the best course of treatment5,11,13-16.

The primary aim of the ChAMP (Chondral Lesions And Meniscus Procedures) Trial was to evaluate the effect on knee pain of arthroscopic debridement (CL-Deb group) compared with observation (CL-noDeb group) of unstable Outerbridge grade-II, III, or IV chondral lesions encountered during APM in patients who were ≥30 years old. The secondary aim was to compare the CL-Deb and CL-noDeb groups with respect to knee function, symptoms, activity, quality of life, and general health. The minimal perceptible clinical improvement using the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) pain score for knee osteoarthritis has been shown to be 9.7 of 100 points, and thus we designed a study that could detect a 10-point difference between the groups17. It was hypothesized that there would be no difference between the CL-Deb and CL-noDeb groups with respect to knee pain and other patient-reported outcomes 1 year after surgery.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The ChAMP Trial is a double-blind randomized controlled trial that investigated the effect of debridement of unstable chondral lesions on pain in patients undergoing APM. Details of the study design and procedures have been published previously18. This study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01527201) and was approved by the institutional review board at our university.

Screening and Randomization

Subjects were recruited by 6 sports medicine fellowship-trained orthopaedic surgeons, and informed consent was obtained from all participants (2012 to 2015). Preoperative inclusion criteria were patients who were ≥30 years old who had persistent symptoms of a meniscal tear for ≥3 months, no evidence of degenerative joint disease on weight-bearing radiographs, and confirmation of a meniscal tear on magnetic resonance imaging and who were scheduled to undergo APM. Intraoperative inclusion criteria were a tear of 1 meniscus or both, and at least 1 unstable chondral lesion, which typically would be treated by debridement. Study exclusion criteria are presented in Table I. All study surgeons met multiple times during the study design phase to review arthroscopic photographs and videos to reach a consensus about defining unstable chondral lesions, and it was agreed that lesions of >1 cm2 with flaps that could be displaced >5 mm with a probe, or that were >1 cm2 and contained fibrillated cartilage involving >50% of the depth of the cartilage, were deemed to be unstable. Patients with unstable chondral flaps that appeared to represent an impending loose body (i.e., a flap that was barely attached to native cartilage and appeared about to detach completely) were excluded from the study (Fig. 1). At the time of surgery, 12 of 48 patients were excluded solely on the basis of this criterion (see Appendix).

TABLE I.

The ChAMP Trial Exclusion Criteria

| Exclusion Criteria |

| Osteochondritis dissecans |

| Radiographic evidence of visible osteophytes of the medial or lateral compartment of the knee |

| Weight-bearing radiographs with evidence of joint space loss in the tibiofemoral compartment of >50% compared with the nonoperatively treated knee |

| Previous knee surgery or major trauma to the operatively treated knee |

| Inflammatory joint disease, chondrocalcinosis, or gout |

| Substantial ligamentous instability in the operatively treated knee |

| Major neurologic deficit (e.g., dementia) |

| Serious medical illness with limited life expectancy or that poses high intraoperative risk |

| Pregnancy |

| Workers’ Compensation claim |

| Absence of a meniscal tear* |

| Large chondral flaps judged to be impending loose bodies† |

| Grade-IV chondral lesions in the patellofemoral compartment of >4 cm2*† |

| Undergoing meniscal repair* |

| Microfracture for contained grade-IV chondral lesions*† |

| Root avulsion tears of either meniscus* |

Confirmed arthroscopically.

The Outerbridge classification was used for grading chondral lesions14.

Fig. 1.

Arthroscopic photograph of a lesion that was considered an impending loose body.

Patients were randomly assigned to CL-Deb or CL-noDeb in a 1:1 ratio using a random-number generator. The randomization sequence was created by an independent study coordinator with no other involvement in this study, and the sequence was stratified by surgeon and allocated in random blocks of 2 and 4. The surgeon opened a sealed envelope during surgery that contained an index card with the treatment allocation written on it. Patients and data collectors were blinded to treatment assignment until the end of the study at 1 year from surgery.

Intervention

APM of the medial or lateral menisci, or both, was performed on all patients, at which time the articular cartilage was examined. Patients with unstable chondral lesions in any compartment of the knee were randomized to CL-Deb or CL-noDeb14,18. For the CL-Deb group, unstable chondral flaps or fibrillated cartilage were excised with a motorized shaver. No osseous debridement or microfracture was performed for any grade-IV lesions. For the CL-noDeb group, all chondral lesions were left intact. Patients received an intra-articular injection of 20 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine at the end of the procedure.

Postoperatively, all patients received a prescription for Lortab (acetaminophen and hydrocodone; one or two 7.5-mg tablets by mouth twice a day as needed) and an order for physical therapy centered on eliminating effusion, regaining full range of motion, and progressive strengthening.

Demographic and Surgical Data

Demographic data included age at initial visit, sex, weight, body mass index (BMI), and the affected knee. Surgical data were documented on standard data forms by the surgeon and included the location and type of meniscal tear, as well as the location and Outerbridge grade of chondral lesion(s)14. For the CL-Deb group, the amount of additional time spent in surgery for the chondral debridement was also recorded.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was the difference between study groups with respect to pain scores obtained from the WOMAC at 1 year from surgery. Scores ranged from 0 (extreme problems) to 100 (no problems)19. Secondary outcome measures included the 1-year differences in WOMAC stiffness and function scores, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Scores (KOOS; pain, symptoms, sports and recreation, and quality-of-life scores), visual analog scale (VAS) pain score, Short Form-36 (SF-36), and physical knee measures (range of motion, quadriceps circumference, and effusion). Outcome scores ranged from 0 (extreme problems) to 100 (no problems) for the KOOS, 0 (no knee pain within the past 24 hours) to 10 (worst possible knee pain within the past 24 hours) for the VAS pain score, and 0 (lowest level of functioning) to 100 (highest level of functioning) for the SF-3620-22. Measures of range of motion included degrees of extension, degrees short of neutral extension, and degrees of flexion. Quadriceps circumference was measured in centimeters at the midportion of the patella and 10 cm proximal to the superior pole. The presence (yes or no) and severity (mild, moderate, or severe) of knee effusion were also assessed.

Assessments

Outcomes were assessed preoperatively and at 8 to 12 days, 6 weeks ± 5 days, 3 months ± 2 weeks, 6 months ± 2 weeks, and 1 year ± 1 month after APM (2012 to 2016) by an assessor who was blinded to treatment group assignment. All outcomes were primarily assessed at 1 year postoperatively, and the earlier postoperative time points were assessed secondarily to examine the overall trajectory of outcomes.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic data and surgical characteristics. The t test for continuous data and the chi-square test (or Fisher exact test) for categorical data were used to derive the p value for comparisons between the CL-Deb and CL-noDeb groups. One outlier (420 lb; 190.5 kg) for weight and 2 outliers (52.46 and 50.63 kg/m2) for BMI, all from the CL-noDeb group, were excluded.

The t tests were used to compare the CL-Deb and CL-noDeb groups preoperatively and at each postoperative assessment. There was a loss to follow-up in each group of approximately 15%. Group comparisons were made with complete data (i.e., without missing data imputation) and after implementing the multiple imputation technique (i.e., with missing data imputation), a popular method for handling missing data in medical research23,24. The multiple imputation technique uses the distribution of the observed data to estimate multiple values that reflect the uncertainty around the true value to fill in the missing data. Then, each of the multiple “imputed” complete data sets was analyzed separately, and the final analysis combined the results from each analyzed data set. In our analysis, we imputed the data set 5 times (the SAS default), and all analyses were done with SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute).

Our sample size calculation was based on a 10-point difference in the WOMAC pain score, which has been shown to be the minimal perceptible clinical improvement in the WOMAC pain score for knee osteoarthritis in a study by Ehrich et al. (mean, 9.7 points; range, 9 to 12 points)17,18. To achieve at least 80% power and accounting for a 15% loss to follow-up, it was determined that a total of 190 patients were needed for randomization.

Results

Characteristics of the Study Sample

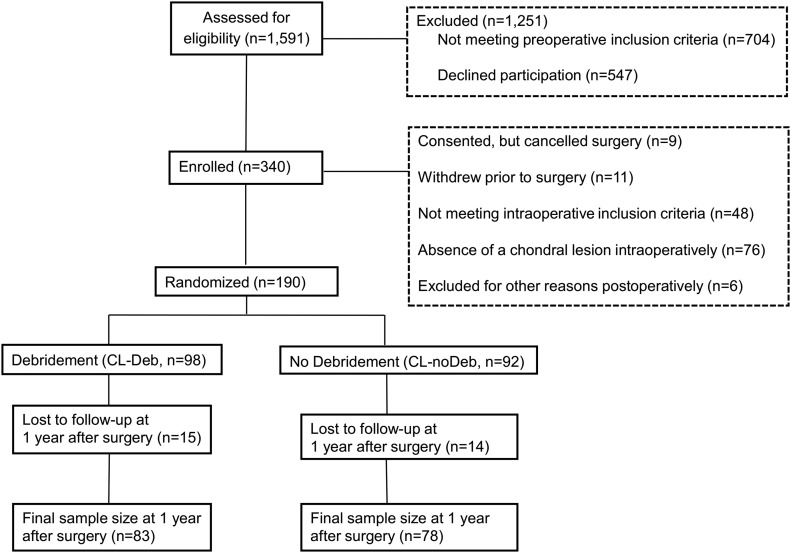

A total of 1,591 patients were assessed for eligibility. Of those, 190 enrolled in the study and were randomized (Fig. 2). There were no significant differences between the groups with respect to demographic data including age, sex, weight, BMI, and affected knee (Table II).

Fig. 2.

The ChAMP Trial sample flowchart.

TABLE II.

Demographic Data for the Chondral Debridement (CL-Deb) and No Chondral Debridement (CL-noDeb) Groups in the ChAMP Trial (N = 190)*

| CL-Deb (N = 98) |

CL-noDeb (N = 92) |

|||

| Demographics | No. Missing | Value | No. Missing | Value |

| Age† (yr) | 0 | 54.9 ± 7.3 | 0 | 54.0 ± 7.9 |

| Sex (no. [%]) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Male | 62 (63.3) | 59 (64.1) | ||

| Female | 36 (36.7) | 33 (35.9) | ||

| Weight† (lb [kg]) | 1 | 192.3 ± 42.3 (87.2 ± 19.19) | 1 | 202.3 ± 38.6 (91.76 ± 17.51)‡ |

| BMI, continuous† (kg/m2) | 1 | 29.1 ± 5.1 | 1 | 30.0 ± 4.6‡ |

| BMI categories (no. [%]) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 3 (3.1) | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Normal weight (18.5 to 24.99 kg/m2) | 15 (15.5) | 10 (11.4) | ||

| Overweight (25 to 29.99 kg/m2) | 42 (43.3) | 30 (34.1) | ||

| Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 37 (38.1) | 47 (53.4)‡ | ||

| Affected knee (no. [%]) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Right | 43 (43.9) | 42 (45.7) | ||

| Left | 55 (56.1) | 50 (54.3) | ||

There were no significant differences between groups with respect to demographic data (p > 0.05 for all).

The values are given as the mean and the standard deviation.

One outlier for weight (420 lb; 190.5 kg) and 2 outliers for BMI (52.46 and 50.63 kg/m2) were excluded from group comparisons.

Surgical Characteristics

The CL-Deb group had significantly more longitudinal medial meniscal tears than the CL-noDeb group (see Appendix). The CL-noDeb group had significantly more chondral lesions and specifically more grade-II and grade-III medial chondral lesions on the patella, as well as more grade-III medial chondral lesions on the tibia. The additional time needed for arthroscopic debridement in the CL-Deb group was a mean (and standard deviation) of 5.01 ± 3.31 minutes.

Outcomes

At 1 year after surgery, there were no significant differences in the primary (WOMAC pain score; Figs. 3 and 4) and secondary outcome measures (WOMAC stiffness and physical function; VAS pain score; KOOS pain, other symptoms, function in sport and recreation, and quality of life; SF-36 pain, physical functioning, and general health; and physical knee measures; see Appendix). At 8 to 12 days after surgery, the CL-noDeb group had more improvement than the CL-Deb group with respect to quality-of-life scores on the KOOS (p = 0.04) and physical functioning on the SF-36 (p = 0.01), as well as increased quadriceps circumference at the midportion of the patella (p = 0.02). At 6 weeks after surgery, the CL-noDeb group had more improvement than the CL-Deb group with respect to the pain scores on the WOMAC (p = 0.02) and KOOS outcome measures (p = 0.04). At 3 months after surgery, the CL-noDeb group had more improvement than the CL-Deb group in terms of physical functioning on the SF-36 (p = 0.01). At 6 months after surgery, the CL-noDeb group had increased quadriceps circumference at 10 cm proximal to the superior pole compared with the CL-Deb group (p = 0.02).

Fig. 3.

The WOMAC pain scores by study group and study visit (without imputation for missing data). The asterisk indicates that there was a significant difference between the groups at 6 weeks (p = 0.02). SD = standard deviation.

Fig. 4.

The WOMAC pain scores by study group and study visit (with imputation for missing data). The asterisk indicates that there was a significant difference between the groups at 6 weeks (p = 0.01). SD = standard deviation.

Adverse Events

No adverse events were reported during this study.

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that arthroscopic debridement is not superior to lavage, sham surgery, and physical and medical therapy for knee osteoarthritis1-4. Study inclusion was based on the presence of knee osteoarthritis and not meniscal injury. The primary aim of the current study was to examine the difference in knee pain at 1 year after debridement compared with observation of unstable chondral lesions encountered in patients undergoing APM. The secondary aim was to examine the differences between the groups at 1 year with respect to knee function, symptoms, activity, quality of life, general health, and physical knee measurements. As hypothesized, we found no significant differences in the primary or secondary outcomes at 1 year. We found that average postoperative pain scores were improved for patients randomly assigned to the CL-noDeb group compared with the CL-Deb group, with the CL-noDeb group having significantly less pain than the CL-Deb group at 6 weeks after surgery. Chondral lesions and meniscal tears are also associated with other knee symptoms including swelling, clicking, and locking, which can subsequently affect range of motion, activity, and general health13,25. Knee function, symptoms, activity, quality of life, and general health were generally better for patients randomly assigned to the CL-noDeb group than for those assigned to the CL-Deb group. However, group differences were only significant for quality of life and physical functioning at 8 to 12 days and for physical functioning at 3 months. Also, there was a significant increase in quadriceps circumference at 8 to 12 days and 6 months after surgery for the CL-noDeb group compared with the CL-Deb group. The CL-noDeb group may have had better outcomes at the earlier time points because debridement resulted in the release of some chondral breakdown products in the knee, causing an inflammatory response and increased pain26. These chemical breakdown products may be absorbed with time, but could delay recovery.

To our knowledge, the ChAMP Trial is the first study to compare outcomes after debridement and those after observation of unstable chondral lesions seen during APM. Several studies have examined outcomes after arthroscopic debridement for knee osteoarthritis1-3,27,28. Two studies have demonstrated a reduction in pain 1 year after arthroscopic debridement for knee osteoarthritis; however, 1 study was lacking a control group27,28. In 3 randomized controlled trials of arthroscopic debridement compared with lavage1-3, sham surgery3, and physical as well as medical therapy for knee osteoarthritis2, no significant differences with respect to pain, function, and quality of life were found at 1 year. Several studies also examined outcomes after APM4,6,9,10. Haviv et al. conducted a case series that demonstrated improved function and pain 1 year after APM in patients without comorbid osteoarthritis9. In a sample of patients with symptomatic meniscal tears and mild to moderate knee osteoarthritis, Katz et al. found no significant differences in pain, physical function, and activity at 6 months and 1 year after APM compared with physical therapy4. Herrlin et al. found no significant differences in pain, physical function, and activity after APM and exercise compared with exercise alone in patients with nontraumatic medial meniscal tears with or without minimal osteoarthritis10. Sihvonen et al. found no significant differences in knee symptoms including pain, as well as function and quality of life, at 1 year after APM compared with sham surgery in patients with a degenerative medial meniscal tear without osteoarthritis6.

Our results suggest that arthroscopic debridement is not superior to observation in treating unstable chondral lesions encountered during APM. Standard practice among orthopaedic surgeons has been to debride these lesions; however, our findings challenge the current standards4. We expect our findings to be challenged on the basis of (1) our study sample, (2) our definition of unstable chondral lesions, (3) the exclusion of patients with impending loose bodies, (4) the fact that we did not limit our study to patients who only had chondral lesions in the same compartment as the meniscal tear, and (5) our method of debridement of unstable lesions. Our response to these concerns is that (1) we included patients best indicated for meniscal surgery on the basis of current evidence-based practice set forth by the European Society of Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery and Arthroscopy (i.e., failure after at least 3 months of nonoperative management, the absence of degenerative joint disease on standing radiographs, and evidence of a meniscal tear on magnetic resonance imaging); (2) we defined unstable chondral lesions on the basis of the consensus of 7 fellowship-trained sports medicine surgeons; (3) only 6% (12) of 190 patients were thought to have a lesion that was an impending loose body; (4) during the study planning phase, we collected pilot data that indicated that few patients undergoing arthroscopy had unstable chondral lesions only in the same compartment as the meniscal tear, so using this criterion would have prolonged study enrollment and limited the generalizability of our results; and (5) we removed only unstable flaps or fibrillated cartilage, and did not extend our debridement to normal cartilage or expose any unexposed subchondral bone.

In 2012, Medicare changed reimbursement for arthroscopic debridement by bundling code 29877 (debridement or shaving of articular cartilage) with 29880 (medial and lateral APM) and 29881 (medial or lateral APM)29,30. Reimbursement for meniscectomies with chondral debridement that would have been coded with 29877 has since decreased by 35%, but the impact of this coding change on the actual number of chondroplasties being performed with APM remains unknown29. A recent study also found that arthroscopic debridement is not cost-effective compared with nonoperative management of knee osteoarthritis31. The results of the current study and changes in reimbursement may alter current clinical practice and lead to a reduction in the rate of arthroscopic debridement.

The strengths of this study include random treatment assignment and the blinding of patients and data collectors to treatment assignment until completion of the study. Outcomes were assessed with standard tools that have been shown to be valid and reliable for patients with knee osteoarthritis19,20,22,32-34. Outcomes were assessed over the course of 1 year, which is an adequate amount of time for patients to achieve the full benefit of APM. We were able to examine the trajectory of outcomes since baseline measures were obtained as well as multiple follow-up measures throughout 1 year. The rate of loss to follow-up was only 15%, which was anticipated and accounted for in the a priori sample size calculation.

There are several limitations to this study. The study findings may not be generalizable to patients on Workers’ Compensation, who were excluded from this study, and to patients diagnosed by a general orthopaedist since the recruiting physicians in this study were fellowship-trained sports medicine surgeons. Surgeon judgment regarding treatment of chondral lesions may have differed, although all surgeons followed a standard randomization protocol, and the randomization scheme was stratified by surgeon to ensure balance between study groups18. Patient-reported outcomes may be subject to recall bias; however, patients were blinded to treatment allocation throughout the study. Several data collectors performed knee examinations at each follow-up visit, which could have affected the interrater reliability of the knee measurements; however; all data collectors were blinded to treatment assignment and followed a standard protocol.

In conclusion, we did not find a difference in knee pain, function, symptoms, activity, quality of life, or general health at 1 year after APM in patients randomized to debridement or observation of unstable chondral lesions. These results suggest that there is no benefit to debridement of unstable chondral lesions encountered during APM, and that debridement may actually delay recovery. It is recommended that these lesions be left in situ.

Appendix

Figures comparing the outcome scores by study group and study visit for all instruments as well as tables showing the frequency of intraoperative exclusion criteria for the ChAMP Trial and the arthroscopic findings for the chondral debridement (CL-Deb) and no chondral debridement (CL-noDeb) groups are available with the online version of this article as a data supplement at jbjs.org (http://links.lww.com/JBJS/C965).

Footnotes

Investigation performed at the Department of Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine, The State University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, New York

A commentary by Jaron P. Sullivan, MD, is linked to the online version of this article at jbjs.org.

Disclosure: This study was funded by the Ralph C. Wilson, Jr. Foundation; however, this entity did not play a role in the investigation. The Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest forms are provided with the online version of the article (http://links.lww.com/JBJS/C964).

References

- 1.Chang RW, Falconer J, Stulberg SD, Arnold WJ, Manheim LM, Dyer AR. A randomized, controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery versus closed-needle joint lavage for patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 1993. March;36(3):289-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirkley A, Birmingham TB, Litchfield RB, Giffin JR, Willits KR, Wong CJ, Feagan BG, Donner A, Griffin SH, D’Ascanio LM, Pope JE, Fowler PJ. A randomized trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med. 2008. September 11;359(11):1097-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moseley JB, O’Malley K, Petersen NJ, Menke TJ, Brody BA, Kuykendall DH, Hollingsworth JC, Ashton CM, Wray NP. A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med. 2002. July 11;347(2):81-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katz JN, Brophy RH, Chaisson CE, de Chaves L, Cole BJ, Dahm DL, Donnell-Fink LA, Guermazi A, Haas AK, Jones MH, Levy BA, Mandl LA, Martin SD, Marx RG, Miniaci A, Matava MJ, Palmisano J, Reinke EK, Richardson BE, Rome BN, Safran-Norton CE, Skoniecki DJ, Solomon DH, Smith MV, Spindler KP, Stuart MJ, Wright J, Wright RW, Losina E. Surgery versus physical therapy for a meniscal tear and osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2013. May 2;368(18):1675-84. Epub 2013 Mar 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim S, Bosque J, Meehan JP, Jamali A, Marder R. Increase in outpatient knee arthroscopy in the United States: a comparison of National Surveys of Ambulatory Surgery, 1996 and 2006. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011. June 1;93(11):994-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, Itälä A, Joukainen A, Nurmi H, Kalske J, Järvinen TL; Finnish Degenerative Meniscal Lesion Study (FIDELITY) Group. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear. N Engl J Med. 2013. December 26;369(26):2515-24. Epub 2013 Dec 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beaufils P, Becker R. ESSKA Meniscus Consensus Project. Luxembourg: ESSKA; 2016. http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.esska.org/resource/resmgr/Docs/2016_DML_full_text.pdf. Accessed 2017 Feb 10. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Østerås H, Østerås B, Torstensen TA. Medical exercise therapy, and not arthroscopic surgery, resulted in decreased depression and anxiety in patients with degenerative meniscus injury. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2012. October;16(4):456-63. Epub 2012 May 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haviv B, Bronak S, Kosashvili Y, Thein R. Which patients are less likely to improve during the first year after arthroscopic partial meniscectomy? A multivariate analysis of 201 patients with prospective follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016. May;24(5):1427-31. Epub 2015 Apr 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herrlin S, Hållander M, Wange P, Weidenhielm L, Werner S. Arthroscopic or conservative treatment of degenerative medial meniscal tears: a prospective randomised trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007. April;15(4):393-401. Epub 2007 Jan 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hjelle K, Solheim E, Strand T, Muri R, Brittberg M. Articular cartilage defects in 1,000 knee arthroscopies. Arthroscopy. 2002. September;18(7):730-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montgomery SR, Foster BD, Ngo SS, Terrell RD, Wang JC, Petrigliano FA, McAllister DR. Trends in the surgical treatment of articular cartilage defects of the knee in the United States. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014. September;22(9):2070-5. Epub 2013 Jul 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDermott I. Meniscal tears, repairs and replacement: their relevance to osteoarthritis of the knee. Br J Sports Med. 2011. April;45(4):292-7. Epub 2011 Feb 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Outerbridge RE. The etiology of chondromalacia patellae. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1961. November;43-B:752-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Widuchowski W, Widuchowski J, Trzaska T. Articular cartilage defects: study of 25,124 knee arthroscopies. Knee. 2007. June;14(3):177-82. Epub 2007 Apr 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arøen A, Løken S, Heir S, Alvik E, Ekeland A, Granlund OG, Engebretsen L. Articular cartilage lesions in 993 consecutive knee arthroscopies. Am J Sports Med. 2004. Jan-Feb;32(1):211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ehrich EW, Davies GM, Watson DJ, Bolognese JA, Seidenberg BC, Bellamy N. Minimal perceptible clinical improvement with the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities osteoarthritis index questionnaire and global assessments in patients with osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2000. November;27(11):2635-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bisson LJ, Kluczynski MA, Wind WM, Fineberg MS, Bernas GA, Rauh MA, Marzo JM, Smolinski RJ. Design of a randomized controlled trial to compare debridement to observation of chondral lesions encountered during partial meniscectomy: The ChAMP (Chondral Lesions And Meniscus Procedures) Trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015. November;45(Pt B):281-6. Epub 2015 Sep 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roos EM, Klässbo M, Lohmander LS. WOMAC osteoarthritis index. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness in patients with arthroscopically assessed osteoarthritis. Western Ontario and MacMaster Universities. Scand J Rheumatol. 1999;28(4):210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roos EM, Roos HP, Lohmander LS, Ekdahl C, Beynnon BD. Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)—development of a self-administered outcome measure. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998. August;28(2):88-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wessel J. The reliability and validity of pain threshold measurements in osteoarthritis of the knee. Scand J Rheumatol. 1995;24(4):238-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992. June;30(6):473-83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. 2nd ed. Hoboken: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mackinnon A. The use and reporting of multiple imputation in medical research - a review. J Intern Med. 2010. December;268(6):586-93. Epub 2010 Sep 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sellards RA, Nho SJ, Cole BJ. Chondral injuries. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2002. March;14(2):134-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pelletier JP, Martel-Pelletier J, Abramson SB. Osteoarthritis, an inflammatory disease: potential implication for the selection of new therapeutic targets. Arthritis Rheum. 2001. June;44(6):1237-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dervin GF, Stiell IG, Rody K, Grabowski J. Effect of arthroscopic débridement for osteoarthritis of the knee on health-related quality of life. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003. January;85(1):10-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hubbard MJ. Articular debridement versus washout for degeneration of the medial femoral condyle. A five-year study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996. March;78(2):217-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elkousy H, Heaps B, Overturf S, Laughlin MS. Financial impact of third-party reimbursement due to changes in the definition of ICD-9 arthroscopy codes 29880, 29881, and 29877. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014. September 17;96(18):e161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LeGrand M. Coding for knee arthroscopy and chondroplasty: guideline changes related to chondroplasty and meniscectomy procedures. AAOS Now. 2012 May. http://www.aaos.org/news/aaosnow/may12/managing1.asp. Accessed 2015 May 20.

- 31.Marsh JD, Birmingham TB, Giffin JR, Isaranuwatchai W, Hoch JS, Feagan BG, Litchfield R, Willits K, Fowler P. Cost-effectiveness analysis of arthroscopic surgery compared with non-operative management for osteoarthritis of the knee. BMJ Open. 2016. January 12;6(1):e009949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988. December;15(12):1833-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Engelhart L, Nelson L, Lewis S, Mordin M, Demuro-Mercon C, Uddin S, McLeod L, Cole B, Farr J. Validation of the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score subscales for patients with articular cartilage lesions of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2012. October;40(10):2264-72. Epub 2012 Sep 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kosinski M, Keller SD, Hatoum HT, Kong SX, Ware JE Jr. The SF-36 Health Survey as a generic outcome measure in clinical trials of patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: tests of data quality, scaling assumptions and score reliability. Med Care. 1999. May;37(5)(Suppl):MS10-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]