Abstract

The authors present the case of a patient that demonstrates resolution of delayed onset hypoglossal nerve palsy (HNP) subsequent to occipital condyle fracture following a motor vehicle accident. Decompression of the hypoglossal nerve and craniocervical fixation led to satisfactory long-term (>5 years) outcome. There is a scarcity of literature in recognizing HNPs following trauma and a lack of pathophysiological understanding to both a delayed presentation and to resolution versus persistence. This is the first report demonstrating long-term resolution of hypoglossal nerve injury following trauma to the craniocervical junction.

Keywords: Cranial nerve palsy, craniocervical fracture, hypoglossal, nerve compression, neuropraxia, occipital condyle fracture, tongue anesthesia

INTRODUCTION

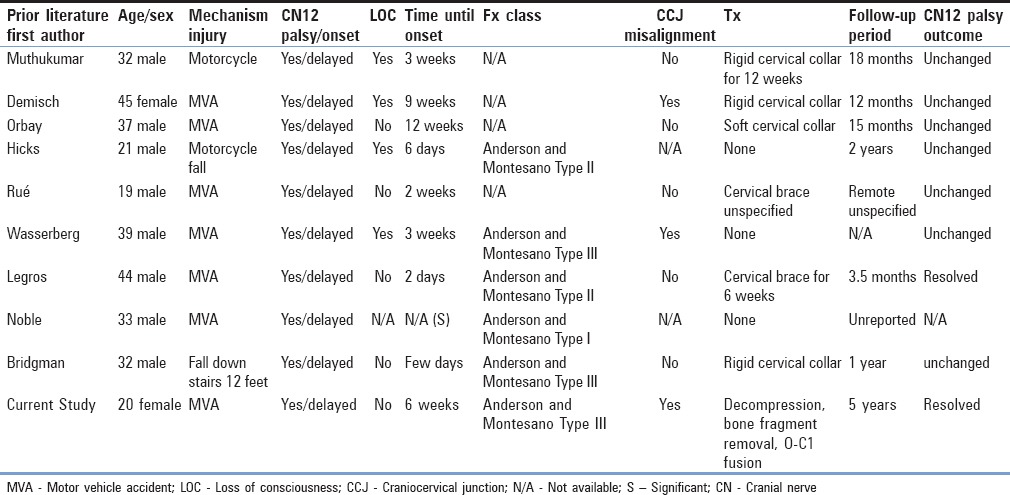

A growing number of reports have illustrated hypoglossal nerve injury after occipital condyle fractures (OCFs).[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9] Despite rare recognition, treatment options remain indicated on the severity of OCF.[10,11] Only one case in the literature has suggested improvement in the subacute presentation of hypoglossal nerve palsy (HNP).[7] Unfortunately, all other studies have demonstrated persistence HNP varying from 3.5 months to 2 years following OCF [Table 1].

Table 1.

Cases of delayed onset hypoglossal nerve palsy after occipital condyle fracture

The exact mechanism by which OCFs contribute to HNP and in the delayed presentation is unclear. Thus far, case reports have demonstrated an association between OCFs and hypoglossal nerve injury [Table 1], but no case has demonstrated causality. Here, we report on a patient in whom an avulsed OCF was identified with a delayed presentation of HNP, and after removal and stabilization, resolution of neuropraxia was demonstrated on long-term follow-up (>5 years).

CASE REPORT

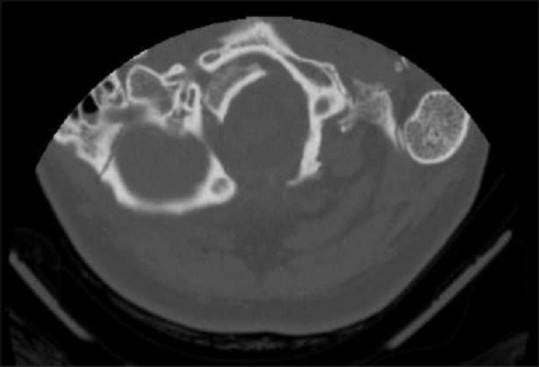

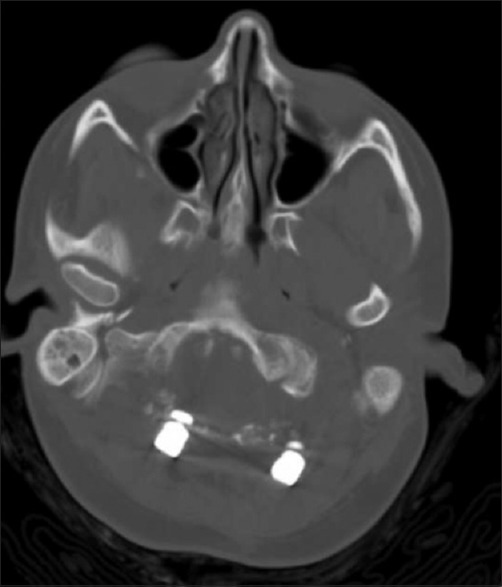

Here, we report on a 20-year-old unrestrained female passenger involved in a motor vehicle accident (MVA) who presented to an outside hospital. Neurological examination revealed no focal deficits on the initial presentation or during inpatient course. She was diagnosed with right hip, pelvis, and OCF and underwent right hip open reduction and internal fixation as well as placed in a hard collar. At 6 weeks, she presented to our institution with a new complaint of rightward tongue deviation. Repeat computed tomography (CT) imaging revealed an Anderson and Montesano (AM) Type III OCF with a large bone fragment resting in the epidural space at the foramen magnum-C1 junction without change from the initial CT imaging study after MVA [Figure 1]. The patient was recommended for surgery and subsequently underwent a limited suboccipital craniectomy with C1 laminectomy, removal of bone fragment in C1 ventrolateral epidural space [Figures 2 and 3] with lysis of arachnoid adhesions, and occiput to C1 fusion [Figure 4]. Postoperatively, her right tongue deviation appeared to improve on postoperative day (POD) 1 and completely resolved by POD 2. On both short- and long-term follow-up, she remained without evidence of tongue deviation at 2 weeks and 5 years, respectively.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography imaging-based evidence of a displaced right occipital condyle fragment in the epidural space adjacent to the hypoglossal canal

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging-based evidence of a displaced right occipital condyle fragment in the epidural space adjacent to the hypoglossal canal

Figure 3.

Postoperative computed tomography scan showing removal of condylar fragment

Figure 4.

Postoperative X-ray demonstrating occipital-cervical fixation from occiput to C1

DISCUSSION

This is the first case in which a causal relationship has been reported between an OCF and neuropraxia of the hypoglossal nerve. We illustrate delayed presentation of unilateral tongue deviation after AM Type III OCF and importantly after surgical decompression with fixation, the palsy resolved. Evidence here, after removal of the avulsed OCF, suggests compression along the deep course of the hypoglossal nerve may contribute to delayed neuropraxia.

Delayed cranial nerve palsies after OCFs are a rare complication, with an incidence of <1%, and unilateral HNP the most commonly reported.[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,12,13] Nine cases of delayed onset isolated HNP after OCFs have been previously reported [Table 1].

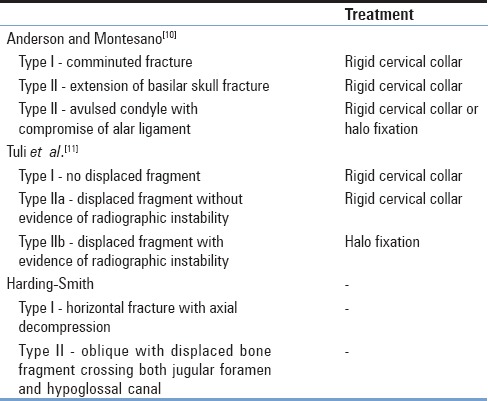

Two popular classification systems for OCFs help guide treatment options [Table 2].[14] The AM system classifies the fracture based on various unrelated factors that allow overlap between types and the Tuli et al. system on the location of the fragment and radiographic evidence of craniocervical joint (CCJ) instability.[10,11,12] AM Type I and II OCFs are treated with rigid cervical orthosis with symptomatic improvements and complete union after 6–12 weeks in the majority of patients.[8,12,14,15] AM Type III OCFs are treated with halo fixation if unstable on flexion-extension imaging or rigid cervical collar if stable.[12,13,15] Despite the current classification systems, their clinical utility is limited since the treatment of the various types is similar.

Table 2.

Classifications of occipital condyle fractures

The exact etiology of the delayed onset HNP after OCF is unknown. The hypothesized mechanisms of delayed onset include callus formation during normal healing applying traction to the hypoglossal nerve as it exits the canal, bone fragment movement impinging on the hypoglossal nerve near the canal, and secondary edema.[1,4,16] Furthermore, airway management has been reported to cause delayed HNP. When considering injury during airway securement, nearly, all HNPs presented in acute or subacute fashion (POD 1–3) and majority resolved within 6 months without intervention, unlike the cases reviewed in this paper.[17,18] Only one of the ten cases of delayed HNP involved intubation in the course of their management,[2] and all presented at least 1 week or later with symptoms persisting for months or greater despite conservative management.

The etiology of our patient's HNP may be related to fracture instability [Figure 5] though no gross movement was identified on repetitive imaging. It is unlikely due to airway management given no recent history of intubation before symptom onset. The patient denied any event, traumatic or infectious, preceding the onset of her HNP.

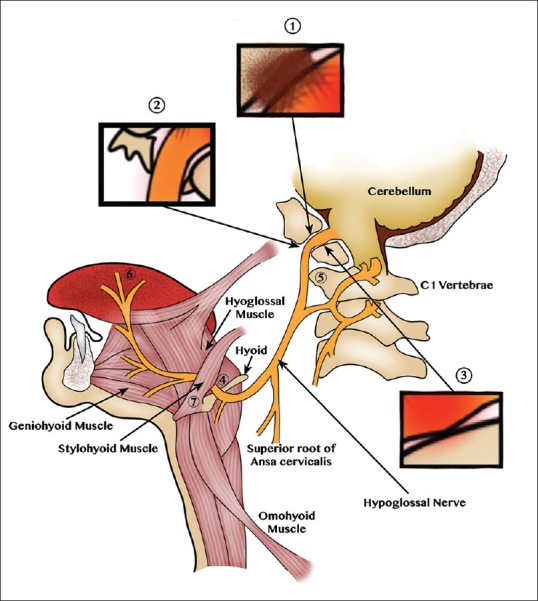

Figure 5.

Illustration of CN12 injury from reported etiologies. Regions of CN12 injury after occipital condyle fracture. (1) Condylar callus with CN12 traction through the canal. (2) Displaced fragment impinges CN12 on canal exit. (3) Edema-induced CN12 compression during canal exit. Regions of CN12 injury during airway management. (4) Superficial CN12 course with resultant impingement. (5) CN12 stretch at the C1 transverse process. (6) Laryngoscope pressure on the tongue with resultant distal CN12 injury. (7) CN12 impingement from a calcified stylohyoid ligament modified from Shah et al.[17]

CCJ misalignment and neural element compression are the predominant indications for surgical intervention despite the classification of fractures,[8,12,13,19,20] although conservative management has been reported for such instances.[21] In our case, the patient presented 6 weeks after her MVA with an acute onset of tongue deviation. The patient was started on steroids and taken to the OR <72 h from onset of symptoms. Due to the acute onset of symptoms and imaging evidence, the patient underwent decompression and posterior stabilization. In the setting of a nonhealed AM Type III condylar fracture, it was presumed that there was instability of the CCJ, and therefore fusion and decompression of the hypoglossal nerve was indicated. The hypoglossal canal was adequately decompressed posteriorly allowing for simultaneous hypoglossal decompression and occiput to C1 fusion without the need for a second stage procedure.

We present a case of HNP resolution after surgical decompression and internal fixation following traumatic OCF. There are currently no well-established treatment guidelines. Most OCFs can be managed conservatively with collar or halo immobilization. Decisions for surgical intervention are based on stability and neurological compression with a correlative neurological examination. Our patient's HNP resolved after decompression, and she continues to remain asymptomatic. Evidence here demonstrates for the first time causality in hypoglossal neuropraxia and OCFs.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Muthukumar N. Delayed hypoglossal palsy following occipital condyle fracture – Case report. J Clin Neurosci. 2002;9:580–2. doi: 10.1054/jocn.2001.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demisch S, Lindner A, Beck R, Zierz S. The forgotten condyle: Delayed hypoglossal nerve palsy caused by fracture of the occipital condyle. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1998;100:44–5. doi: 10.1016/s0303-8467(97)00111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orbay T, Aykol S, Seçkin Z, Ergün R. Late hypoglossal nerve palsy following fracture of the occipital condyle. Surg Neurol. 1989;31:402–4. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(89)90076-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castling B, Hicks K. Traumatic isolated unilateral hypoglossal nerve palsy – Case report and review of the literature. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;33:171–3. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(95)90292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rué M, Jecko V, Dautheribes M, Vignes JR. Delayed hypoglossal nerve palsy following unnoticed occipital condyle fracture. Neurochirurgie. 2013;59:221–3. doi: 10.1016/j.neuchi.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wasserberg J, Bartlett RJ. Occipital condyle fractures diagnosed by high-definition CT and coronal reconstructions. Neuroradiology. 1995;37:370–3. doi: 10.1007/BF00588014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Legros B, Fournier P, Chiaroni P, Ritz O, Fusciardi J. Basal fracture of the skull and lower (IX, X, XI, XII) cranial nerves palsy: Four case reports including two fractures of the occipital condyle – A literature review. J Trauma. 2000;48:342–8. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200002000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noble ER, Smoker WR. The forgotten condyle: The appearance, morphology, and classification of occipital condyle fractures. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17:507–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bridgman SA, McNab W. Traumatic occipital condyle fracture, multiple cranial nerve palsies, and torticollis: A case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 1992;38:152–6. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(92)90094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson PA, Montesano PX. Morphology and treatment of occipital condyle fractures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1988;13:731–6. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198807000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuli S, Tator CH, Fehlings MG, Mackay M. Occipital condyle fractures. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:368–76. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199708000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Theodore N, Aarabi B, Dhall SS, Gelb DE, Hurlbert RJ, Rozzelle CJ, et al. Occipital condyle fractures. Neurosurgery. 2013;72(Suppl 2):106–13. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e3182775527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caroli E, Rocchi G, Orlando ER, Delfini R. Occipital condyle fractures: Report of five cases and literature review. Eur Spine J. 2005;14:487–92. doi: 10.1007/s00586-004-0832-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leone A, Cerase A, Colosimo C, Lauro L, Puca A, Marano P. Occipital condylar fractures: A review. Radiology. 2000;216:635–44. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.3.r00se23635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malham GM, Ackland HM, Jones R, Williamson OD, Varma DK. Occipital condyle fractures: Incidence and clinical follow-up at a level 1 trauma centre. Emerg Radiol. 2009;16:291–7. doi: 10.1007/s10140-008-0789-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Urculo E, Arrazola M, Arrazola M, Jr, Riu I, Moyua A. Delayed glossopharyngeal and vagus nerve paralysis following occipital condyle fracture. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:522–5. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.84.3.0522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah AC, Barnes C, Spiekerman CF, Bollag LA. Hypoglossal nerve palsy after airway management for general anesthesia: An analysis of 69 patients. Anesth Analg. 2015;120:105–20. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cariati P, Cabello A, Galvez PP, Sanchez Lopez D, Garcia Medina B. Tapia's syndrome: Pathogenetic mechanisms, diagnostic management, and proper treatment: A case series. J Med Case Rep. 2016;10:23. doi: 10.1186/s13256-016-0802-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mueller FJ, Fuechtmeier B, Kinner B, Rosskopf M, Neumann C, Nerlich M, et al. Occipital condyle fractures. Prospective follow-up of 31 cases within 5 years at a level 1 trauma centre. Eur Spine J. 2012;21:289–94. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1963-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maserati MB, Stephens B, Zohny Z, Lee JY, Kanter AS, Spiro RM, et al. Occipital condyle fractures: Clinical decision rule and surgical management. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;11:388–95. doi: 10.3171/2009.5.SPINE08866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young WF, Rosenwasser RH, Getch C, Jallo J. Diagnosis and management of occipital condyle fractures. Neurosurgery. 1994;34:257–60. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199402000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]