Abstract

Before an infection can be completely established, the host immediately turns on the innate immune system through activating the interferon (IFN)-mediated antiviral pathway. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) utilizes a unique antagonistic mechanism of type I IFN-mediated host antiviral immunity by incorporating four viral interferon regulatory factors (vIRF1-4). Herein, we characterized novel immune evasion strategies of vIRF4 to inhibit the IRF7-mediated IFN-α production. KSHV vIRF4 specifically interacts with IRF7, resulting in inhibition of IRF7 dimerization and ultimately suppresses IRF7-mediated activation of type I IFN. These results suggest that each of the KSHV vIRFs, including vIRF4, subvert IFN-mediated anti-viral response via different mechanisms. Therefore, it is indicated that KSHV vIRFs are indeed a crucial immunomodulatory component of their life cycles.

Keywords: KSHV, vIRF4, IRF7, Innate immunity, IFN-alpha

1. Introduction

Viral infection generally induces type I interferons (IFNs) that play a crucial role in the first line of host defense mechanism against viral infection. These IFNs are upregulated by interferon regulatory factors (IRFs), which serve as transcriptional factors [1]. Among them, IRF3 and IRF7 especially act as direct transducers of viral-mediated type I IFN gene induction. In brief, both IRF3 and IRF7 undergo phosphorylation, dimerization, and translocation into the nucleus upon virus infection, leading to activation of broader spectrum of type I IFNs, such as IFN-α and IFN-β [2]. Although IRF3 and IRF7 have significantly similar mode of action and function, they have differential effects on the expression of type I IFN genes; IRF7 effectively activates both IFN-α and IFN-β, whereas IRF3 plays a role as a potent activator of IFN-β but not IFN-α [2]. Thus, viruses evolutionally have employed various immune evasion strategies to protect themselves from the host IFN-mediated innate immune responses.

Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) has been identified as an etiologic agent of kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) [3], and multicentric castleman’s disease (MCD) [4]. In order to establish its life cycle, KSHV harbors numerous immunomodulatory genes that hijacks the host antiviral immune responses, including IRFs-mediated innate anti-viral response [5]. In particular, KSHV harbors four viral IRFs (vIRFs) with a significant homology to the cellular IRF family transcription factors. Mounting data indicate that KSHV vIRF1-3, but not vIRF4, target the function of either IRF3 or IRF7 to effectively suppress type I IFN responses. For instance, vIRF1 and vIRF2 have been shown to repress IRF3-mediated IFN-signaling, while vIRF3 has been shown to suppress IRF7-mediated IFN-signaling [6–8]. Overall, it is indicated that suppression of the IFN signaling pathway is a common characteristic of vIRFs (vIRF1-3), while the potential function of vIRF4 in IFN-mediated innate immunity still remains to be characterized.

Herein, we show that vIRF4 specifically interacts with IRF7, but not IRF3, leading to the prevention of IRF7 dimerization. Ultimately, vIRF4 blocks IFN-α signaling that prevents the ability of the cells to respond upon viral infection. Our study reveals a novel function of KSHV vIRF4 in the IFN-mediated host immune surveillance. These results indicate that KSHV vIRF proteins are crucial virulent factors that robustly suppress type I IFN-mediated immune response, which ensure the generation of a favorable environment for its life cycle.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Cell culture, cell line construction, and transfections

293T and tetracycline-inducible TREx293 cells [9,10] were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin (P/S). For generation of tetracycline-inducible TREx293 cells expressing vIRF4, TREx293 cells were transfected with pcDNA/FRT/To-vIRF4/AU along with the pOG44 Flp recombinase expression vector in the presence of 200 μg/ml of hygromycin B (Invitrogen) [10]. Tetracycline-inducible TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4-AU cells [9,10] were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 U/ml P/S. Plasmid DNA transfection was performed with polyethylenimine (PEI) (Sigma) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Doxycycline (Doxy) was purchased from Sigma and treated with 1 μg/ml for the indicated periods of time. Cells were treated with 1000 U/ml of IFN-β (Sigma).

2.2. Plasmid construction

The pcDNA5/FRT/To-Hygro expression vIRF4 was described previously [10]. DNA fragments corresponding to the coding sequences of the wild-type (WT) vIRF4 gene were amplified from the template DNA [10] using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and were subsequently subcloned into the pEF IRES-V5 expression vector. Both Flag-tagged IRF7 and IRF3 plasmids were kindly provided by Dr. Jae U. Jung, University of Southern California. Both GST-IRF7 and -IRF3 were PCR amplified and inserted between the BamHI and NotI sites of pEBG vector. All plasmid constructs were sequenced and verified for 100% correspondence with the original sequence.

2.3. Antibodies

Primary antibodies were purchased from the following sources: IRF7 (G-8) antibody from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), Tubulin, Flag, GST, and V5 antibodies from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), and Au antibody from Covance (Princeton, NJ).

2.4. Quantitative real-time (qRT)-PCR

Total RNAs were purified using TRI Reagent™ (Sigma) and reverse-transcription was performed with the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (BIO-RAD). Transcript expression was measured by qRT-PCR using SYBR green-based detection methods in a CFX96™ real-time system (BIO-RAD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The oligonucleotides used were as follows: IFN-α1 (5′-GGA CCT TGA TGC TCC TGG CAC AAA-3′ and 5′-TCT AGG AGG TCC TCA TCC CAA GCA-3′), IFN-α4 (5′-GAG GGC CTT GAT ACT CCT GGC ACA-3′ and 5′-TCTAGG AGG CTC TGT TCC CAA GCA-3′), IFN-α6 (5′-AGA TTT CCC CAG GAG GAG TTT GAT-3′ and 5′-CCG ATC CAC ACG GAG TAC TT-3′), and β-Actin (5′-TGG ACA TCC GCA AAG ACC TG-3′ and 5′-CCG ATC CAC ACG GAG TAC TT-3′). Results were normalized by 18S expression. Relative results of qRT-PCR were made based on the average of at least two independent experiments.

2.5. Luciferase reporter assay

293T cells were co-transfected with the indicated plasmids, luciferase reporter plasmid, and the pRL-SV40 plasmid as an internal control. Using a dual luciferase assay kit (Promega), cells were harvested at 24 h after transfection and lysed with cell lysis reagent (Promega). Subsequently, lysate was incubated with a luciferase assay reagent (Promega). The firefly luciferase activity was measured with a luminometer (Berthold) and normalized to the renilla luciferase activity.

3. Results and discussion

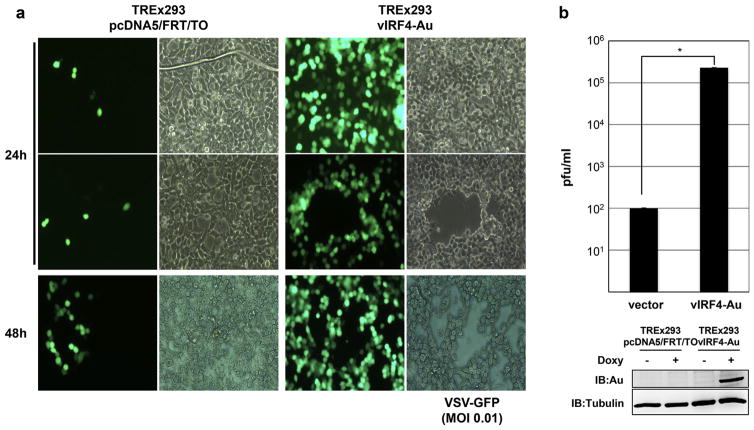

3.1. KSHV vIRF4 robustly stimulates VSV replication

Since KSHV vIRF1, −2, and −3 genes are functionally redundant in suppressing IFN-mediated antiviral response, we examined the potential effect of vIRF4 on the replication of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV). To do this, we first generated 293 cells that ectopically express the carboxyl-terminal Au-tagged vIRF4 in a tetracycline-inducible manner, subsequently called as TREx293 vIRF4-AU [10]. To assess the ability of vIRF4 in inhibiting IFN-mediated antiviral response, TREx293 pcDNA5 and TREx293 vIRF4-AU cells were incubated with Doxycycline (Doxy), serving as a stand-in for tetracycline, for 24 h and infected with VSV-GFP at an MOI of 0.01 for indicated points of time (Fig. 1a). Subsequently, supernatants were collected for determining the titers of the infectious progeny virus by plaque assays (Fig. 1b). Moreover, in order to rule out the possibility of infecting with varying amount of input virus, the inocula were harvested after adsorption and assayed for virus titer and was shown that the cells were infected with same amount virus (data not shown). Our results showed that cytopathic effect of VSV-GFP infection considerably increased in TREx293 vIRF4-AU cells compared to that of TREx293 pcDNA5 cells (Fig. 1a). In correspondence to this data, the replication of VSV-GFP was dramatically enhanced in TREx293 vIRF4-AU cells, as expected (Fig. 1b). These data indicate that the overexpression of vIRF4 might block the IFN-mediated antiviral immune response, ultimately enhancing the replication of VSV-GFP.

Fig. 1. Expression of KSHV vIRF4 robustly facilitates VSV replication.

(a) Effect of KSHV vIRF4 on VSV-GFP propagation. TREx293 pcDNA and TREx293 vIRF4/AU cells upon Doxy (1 μg/ml) treatment were infected with VSV carrying GFP at an MOI of 0.01. At 24 h and 48 h post-infection, the level of VSV replication was monitored by microscopic observation of VSV-induced cytopathic effect. (b) Plaque assay of VSV-GFP upon KSHV vIRF4 expression. Cells were infected with VSV carrying GFP at an MOI of 0.01. The cell culture media was collected at 48 h post-infection. The viral titer was determined by plaque assays. The data are represented as means of triplicate infection ± s.d. An asterisk (*) represents P < 0.001.

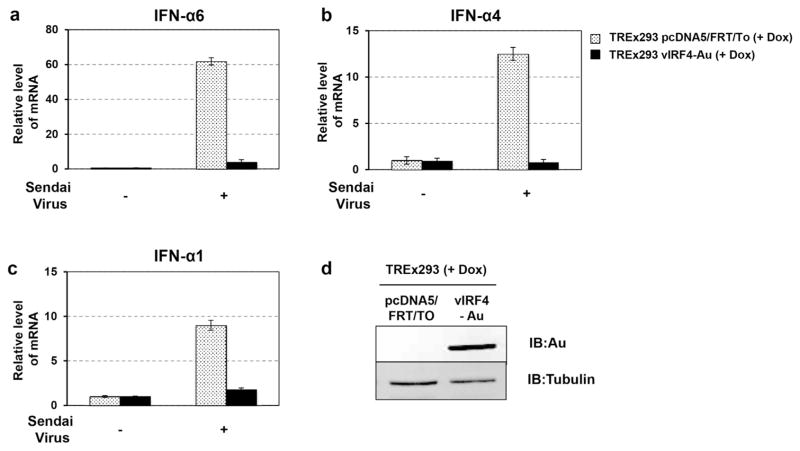

3.2. KSHV vIRF4 suppresses type I IFN production

As the data suggest that vIRF4 blocks the IFN-mediated immune response against VSV-GFP, we further measured the endogenous mRNA levels of type I IFNs in the presence or absence of vIRF4 expression. In order to do so, TREx293 pcDNA5 and TREx293 vIRF4-AU cells were first treated with Doxy for 24 h and were subsequently infected with Sendai Virus (SeV). After 16 h post infection with SeV, the cells were harvested for isolation of total RNAs. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using primers specific to the human IFN-α1, IFN-α4, and IFN-α6 genes. Upon SeV infection, a marked increase of IFN-α1, IFN-α4, and IFN-α6 mRNAs was detected in TREx293 pcDNA5 cells, while ectopic expression of KSHV vIRF4 rapidly suppressed SeV-induced IFN-α1, IFN-α4, and IFN-α6 mRNA levels (Fig. 2a–c). These results indicate that vIRF4 efficiently suppresses virus-induced IFN-α production.

Fig. 2. KSHV vIRF4 suppresses IFN-α production.

(a–c) TREx293 pcDNA and TREx293 vIRF4/AU cells together with Doxy (1 μg/ml) treatment were infected with SeV. At 24 h post-infection, total RNA was extracted from the cells infected with 20 hemagglutination (HA) units of SeV. The expression of IFN-α1, IFN-α4, and IFN-α6 were examined by real time PCR. The data are represented as means of triplicate PCR analysis ± s.d. (d) The vIRF4 expression level was monitored by immunoblot (IB) analyses.

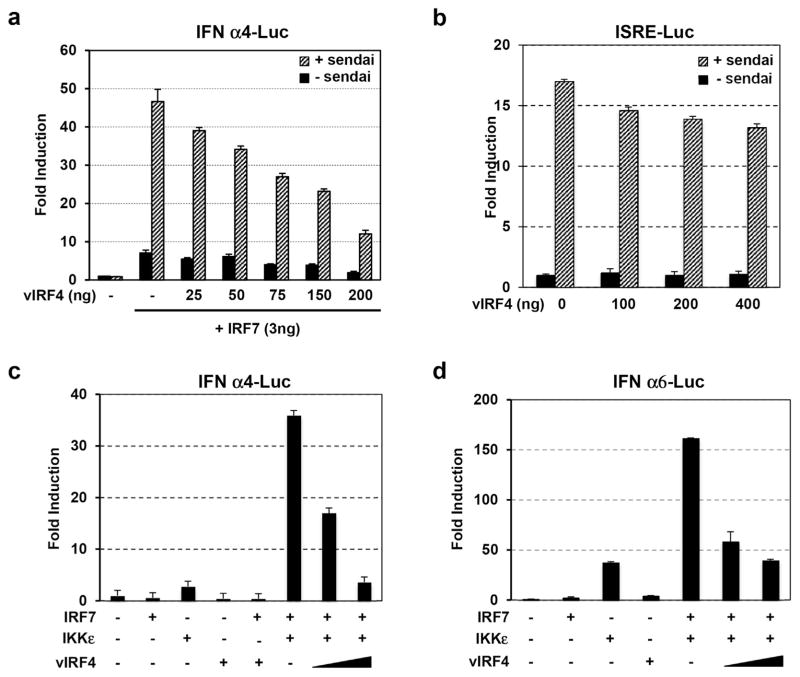

3.3. KSHV vIRF4 inhibits RF7-mediated activation of IFN-α promoter activity

In order to ascertain that vIRF4 has the capability of inhibiting IFN signal transduction, we first tested its effects on the activation of IFN-α4 and IFN-α6 promoters, which are regulated primarily by IRF7 [2,11,12]. 293T cells were transfected with IFN-α4 promoter, V5-vIRF4, or IRF7, individually, as well as in combination. At 24 h post-transfection, the cells were treated with SeV, followed by incubation for an additional 24 h for luciferase assay. Corresponding with other reported studies [13], IRF7 dramatically stimulated IFN-α4 promoter activity upon SeV infection, whereas vIRF4 expression considerably blocked IRF7 transcriptional activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3a). However, vIRF4 expression showed no effect on ISRE (IFN-stimulated responsive element) promoter activity (Fig. 3b). We next examined whether vIRF4 also inhibits IKKε or TBK1-associated activation of IRF7 transcriptional activity, given that the expression of either IKKε or TBK1 kinases lead to phosphorylation of IRF7. 293T cells were co-transfected with various combinations of IFN-α4 promoter (or IFN-α6 promoter), IKKε, IRF7, and vIRF4. As previously shown [13,14], expression of IKKε kinases led to the activation of IRF7 transcriptional activity, resulting in a marked increase of both IFN-α4 and IFN-α6 promoter activities (Fig. 3c and d). However, co-expression of vIRF4 efficiently suppressed IKKε kinase-mediated activation of IRF7 transcriptional activity (Fig. 3c and d). Taken together, our results indicate that KSHV vIRF4 efficiently blocks IRF7-mediated activation of IFN-α promoter activity, contributing to the inhibition of type I IFN signaling.

Fig. 3. Expression of vIRF4 Inhibits IRF7-mediated activation of IFN promoter activity.

293T cells were transfected with 100 ng of pGL3-based IFN-α4 (IFN-α6 or ISRE) promoter construct and 10 ng of pRL-SV40 renilla. Luciferase activity was measured as described in material and method. (a) 293T cells were transfected with increasing amounts of vIRF4 with or without IRF7. At 24 h post-transfection, the cells were stimulated with 20 HA units of SeV infection. (b) 293T cells were transfected with increasing amounts of vIRF4, followed by stimulation of SeV infection for 12 h after 24 h post-transfection. (c and d) 293T cells were transfected with IFN-α4 or IFN-α6 promoter-directed luciferase (luc) reporter, renilla luciferase reporter, IRF7, and IKKε plasmid along with increasing amount of vIRF4.

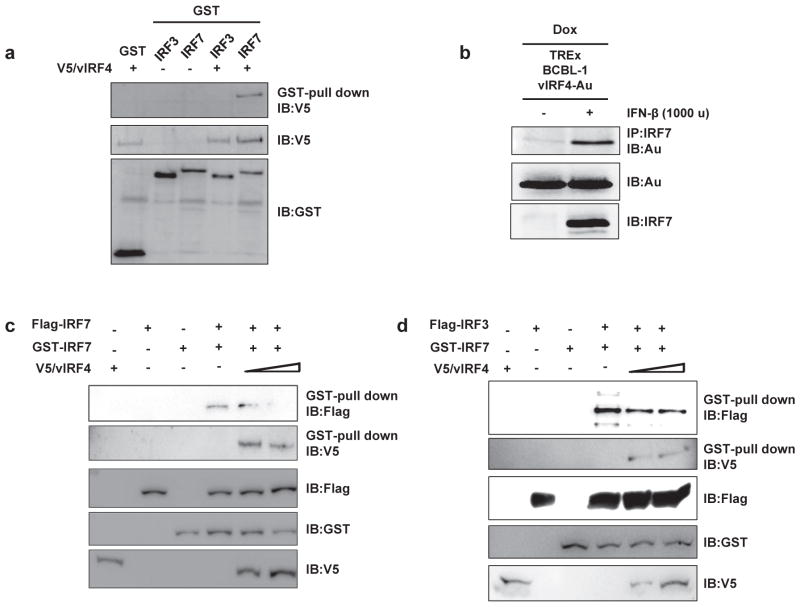

3.4. KSHV vIRF4 interaction with IRF7 inhibits the dimerization of IRF7

Although IRF7 and IRF3 are both critical transcription regulators of type I IFN gene expression, they have different mode of activation, such at IRF7 primarily activates IFN-α promoter activity while IRF3 mainly induces IFN-β promoter activity [11,15,16]. Thereby, we first examined whether vIRF4 affects SeV infection-induced phosphorylation level of IRF7. However, in contrary to our expectation, we could not recognize any difference in the phosphorylation level of IRF7 upon vIRF4 expression (data not shown). Therefore, we next investigated whether vIRF4 interacts with IRF7 to suppress IRF7-mediated IFN-α promoter activity. To this end, 293T cells were co-transfected with plasmid encoding GST-tagged IRF7 or GST-tagged IRF3 along with V5-tagged vIRF4. At 48 h post-transfection, the cells were harvested for GST-pull down assay, followed by immunoblotting (IB) with anti-V5 or anti-GST antibodies, respectively. The IB result showed that vIRF4 specifically interacts with IRF7, but not IRF3 (Fig. 4a). To further confirm the interaction between vIRF4 and endogenous IRF7, we utilized vIRF4-expressing KSHV-infected BCBL-1 cells under tetracycline inducible manner for subsequent investigation. Following the induction of vIRF4 expression in BCBL-1 cells, the cells were treated with IFN-β and were examined for interaction of vIRF4 with endogenous IRF7. Co-immunoprecipitation showed that vIRF4 efficiently interacts with endogenous IRF7 in KSHV-infected BCBL-1 cells (Fig. 4b). Collectively, these data indicate that KSHV vIRF4-IRF7 interaction is involved in suppression of IRF7 activity for production of type I IFN response.

Fig. 4. Interaction of vIRF4 with IRF7 Inhibits dimerization of IRF7.

Interaction between vIRF4 and IRF7. (a) 293T cells were transfected with either GST-fused IRF7 or GST-fused IRF3 together with V5-tagged vIRF4 as indicated. Cell lysates were used for GST-pull down assay, followed by IB with anti-V5 antibody. (b) TRExBCBL1-vIRF4 cells were stimulated with Doxy (1 μg/ml) for 12 h, followed by treatment with IFN-β for 12 h to induce expression of vIRF4 and IRF7. Cell lysates were used for immunoprecipitation with an anti-IRF7 antibody and subsequently, for IB analysis with anti-V5 antibody. (c) Cells were transfected with GST-IRF7 and Flag-IRF7 together with increasing amount of vIRF4 (wt). At 48 h post-transfection, cell lysate were used for GST pull-down assay, followed by IB with anti-Flag antibody or anti-V5 antibody to detect IRF7 homodimerization. (d) Cells were transfected with GST-IRF7 and Flag-IRF3 together with increasing amounts of vIRF4 (wt) and subsequently analyzed in GST pull-down assay, followed by IB with anti-Flag antibody or anti-V5 antibody to detect IRF7-IRF3 heterodimerization.

Owing to understanding the detailed molecular mechanism behind vIRF4-mediated inhibition of IRF7 transcription activity, we first investigated the effect of vIRF4 on dimerization of IRF7 among different processes of IRF7 activation. 293T cells were transfected with different combinations of GST-IRF7, Flag-IRF7, Flag-IRF3, or V5-vIRF4. The cells were then subsequently harvested for GST-pull down assay followed by analysis via IB. As demonstrated in previous studies [11], IRF7 formed either homodimerization or heterodimerization with IRF3 (Fig. 4c and d, lane 4). However, co-expression of vIRF4 effectively inhibited the homodimerization of IRF7 and heterodimerization of IRF7 with IRF3 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4c and d, lane 5 and lane 6). These results collectively indicate that vIRF4 efficiently blocks IRF7 dimerization by interacting with IRF7, ultimately suppressing IRF7-mediated IFN-α transcriptional activity.

IRF7 is a crucial regulator of IFN response, which is the first line of defense mechanism utilized by the host innate immune system to protect itself upon virus infection. Hence, there exists a need for the viruses to manipulate the host immune surveillance mechanism to facilitate their propagation efficiently [1,8]. Because of this, KSHV encodes for various immunomodulatory proteins, including four vIRFs (vIRF1 to 4) that are homologous to cellular IRFs [17]. Accumulated results showed that vIRF1, vIRF2, and vIRF3 counteract IFN-mediated anti-viral activity of the host [7,18–22]. Specifically, vIRF3 suppresses IRF7-mediated IFN-α production through inhibition of the IRF7 binding to DNA [7]. In addition, vIRF1 interferes with CBP/p300-IRF3 complex resulting in the prevention of IRF3-mediated transcriptional activation [22]. Herein, we report that KSHV vIRF4 specifically interacts with IRF7, leading to an inhibition of IRF7 dimerization, and ultimately suppressing IRF7-mediated IFN-α production. Our current study thus adds vIRF4 to the growing family of viral proteins that suppress cellular IRF7-mediated transcriptional activity via protein-protein interactions. More importantly, our study clearly demonstrates that KSHV vIRFs have common biological functions of inhibiting type I IFN-mediated innate immunity. Furthermore, this study demonstrates that vIRFs are crucial in enhancement of KSHV infectivity and persistency. Further study is necessary to elucidate the biological relevance of each vIRF or all four vIRFs together in the context of KSHV genome.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2016R1D1A1B03931761) and by the BK21 plus. We thank Dr. Jae U. Jung for providing reagents and also thank Dr. Jung’s lab members for their supports and discussions.

Footnotes

Transparency document

Transparency document related to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.03.101.

References

- 1.Lee HR, Choi UY, Hwang SW, Kim S, Jung JU. Viral inhibition of PRR-mediated innate immune response: learning from KSHV evasion strategies. Mol Cells. 2016;39:777–782. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2016.0232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Honda K, Taniguchi T. IRFs: master regulators of signalling by Toll-like receptors and cytosolic pattern-recognition receptors. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:644–658. doi: 10.1038/nri1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cesarman E, Chang Y, Moore PS, Said JW, Knowles DM. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1186–1191. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505043321802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dupin N, Diss TL, Kellam P, Tulliez M, Du MQ, Sicard D, Weiss RA, Isaacson PG, Boshoff C. HHV-8 is associated with a plasmablastic variant of Castleman disease that is linked to HHV-8-positive plasmablastic lymphoma. Blood. 2000;95:1406–1412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee HR, Brulois K, Wong L, Jung JU. Modulation of immune system by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus: lessons from viral evasion strategies. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:44. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Areste C, Mutocheluh M, Blackbourn DJ. Identification of caspase-mediated decay of interferon regulatory factor-3, exploited by a Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus immunoregulatory protein. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:23272–23285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.033290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joo CH, Shin YC, Gack M, Wu L, Levy D, Jung JU. Inhibition of interferon regulatory factor 7 (IRF7)-mediated interferon signal transduction by the Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus viral IRF homolog vIRF3. J Virol. 2007;81:8282–8292. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00235-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee HR, Amatya R, Jung JU. Multi-step regulation of innate immune signaling by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Virus Res. 2015;209:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakamura H, Lu M, Gwack Y, Souvlis J, Zeichner SL, Jung JU. Global changes in Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated virus gene expression patterns following expression of a tetracycline-inducible Rta transactivator. J Virol. 2003;77:4205–4220. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.7.4205-4220.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee HR, Toth Z, Shin YC, Lee JS, Chang H, Gu W, Oh TK, Kim MH, Jung JU. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus viral interferon regulatory factor 4 targets MDM2 to deregulate the p53 tumor suppressor pathway. J Virol. 2009;83:6739–6747. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02353-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Honda K, Yanai H, Negishi H, Asagiri M, Sato M, Mizutani T, Shimada N, Ohba Y, Takaoka A, Yoshida N, Taniguchi T. IRF-7 is the master regulator of type-I interferon-dependent immune responses. Nature. 2005;434:772–777. doi: 10.1038/nature03464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sato M, Suemori H, Hata N, Asagiri M, Ogasawara K, Nakao K, Nakaya T, Katsuki M, Noguchi S, Tanaka N, Taniguchi T. Distinct and essential roles of transcription factors IRF-3 and IRF-7 in response to viruses for IFN-alpha/beta gene induction. Immunity. 2000;13:539–548. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Au WC, Su Y, Raj NB, Pitha PM. Virus-mediated induction of interferon A gene requires cooperation between multiple binding factors in the interferon alpha promoter region. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24032–24040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chau TL, Gioia R, Gatot JS, Patrascu F, Carpentier I, Chapelle JP, O’Neill L, Beyaert R, Piette J, Chariot A. Are the IKKs and IKK-related kinases TBK1 and IKK-epsilon similarly activated? Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Civas A, Island ML, Genin P, Morin P, Navarro S. Regulation of virus-induced interferon-A genes. Biochimie. 2002;84:643–654. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(02)01431-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hiscott J. Triggering the innate antiviral response through IRF-3 activation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:15325–15329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700002200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cunningham C, Barnard S, Blackbourn DJ, Davison AJ. Transcription mapping of human herpesvirus 8 genes encoding viral interferon regulatory factors. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:1471–1483. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morin G, Robinson BA, Rogers KS, Wong SW. A rhesus rhadinovirus viral interferon (IFN) regulatory factor is virion associated and inhibits the early IFN antiviral response. J Virol. 2015;89:7707–7721. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01175-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobs SR, Gregory SM, West JA, Wollish AC, Bennett CL, Blackbourn DJ, Heise MT, Damania B. The viral interferon regulatory factors of kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus differ in their inhibition of interferon activation mediated by toll-like receptor 3. J Virol. 2013;87:798–806. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01851-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mutocheluh M, Hindle L, Areste C, Chanas SA, Butler LM, Lowry K, Shah K, Evans DJ, Blackbourn DJ. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus viral interferon regulatory factor-2 inhibits type 1 interferon signalling by targeting interferon-stimulated gene factor-3. J Gen Virol. 2011;92:2394–2398. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.034322-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burysek L, Pitha PM. Latently expressed human herpesvirus 8-encoded interferon regulatory factor 2 inhibits double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase. J Virol. 2001;75:2345–2352. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.5.2345-2352.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin R, Genin P, Mamane Y, Sgarbanti M, Battistini A, Harrington WJ, Jr, Barber GN, Hiscott J. HHV-8 encoded vIRF-1 represses the interferon antiviral response by blocking IRF-3 recruitment of the CBP/p300 coactivators. Oncogene. 2001;20:800–811. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]