Abstract

AIDS is a devastating and deadly disease that affects people worldwide and, like all infections, it comes without warning. Specifically, childbearing women with AIDS face constant psychological difficulties during their gestation period, even though the pregnancy itself may be normal and healthy. These women have to deal with the uncertainties and the stress that usually accompany a pregnancy, and they have to live with the reality of having a life-threatening disease; in addition to that, they also have to deal with discriminating and stigmatizing behaviors from their environment. It is well known that a balanced mental state is a major determining factor to having a normal pregnancy and constitutes the starting point for having a good quality of life. Even though the progress in both technology and medicine is rapid, infected pregnant women seem to be missing this basic requirement. Communities seem unprepared and uneducated to smoothly integrate these people in their societies, letting the ignorance marginalize and isolate these patients. For all the aforementioned reasons, it is imperative that society and medical professionals respond and provide all the necessary support and advice to HIV-positive child bearers, in an attempt to allay their fears and relieve their distress. The purpose of this paper is to summarize the difficulties patients with HIV infection have to deal with, in order to survive and merge into society, identify the main reasons for the low public awareness, discuss the current situation, and provide potential solutions to reducing the stigma among HIV patients.

Keywords: AIDS, stigma, pregnancy, HIV, infection, society, social discrimination

Introduction

Traditionally, women have occupied positions in the health care professions. At the same time, they have also been recipients of health care services. In recent years, studies of women have greatly increased, and the subject of women and health has received a great deal of attention. Many research programs have been carried out by physicians, psychologists, sociologists, and historians. One of the topics that has been extensively studied during gestation is HIV-AIDS. AIDS is considered to be one of the most devastating infections during gestation, having both medical and ethical implications; as a result, women are trapped between social obstacles.1–3

It is indisputable that mental health is the primary requirement for a healthy gestation, and the main impetus of women’s well-being. Unfortunately, women living with HIV-AIDS are quite often stigmatized; a stigma that persists to this day. This process fills them with feelings of shame and guilt, feelings that definitely do not help them maintain a good self-esteem and a healthy mental state. Women possess and guard the right to childbearing. However, HIV-positive pregnant women face depressing and suicidal thoughts, as HIV-related stigma and discrimination govern their lives.4 The presence of stigma and discrimination inevitably leads to significant physical, psychological, and economical side effects. The stigma permeates and disintegrates social structure.5,6

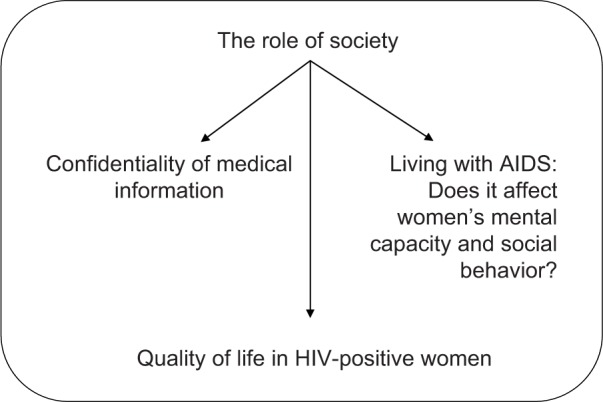

Numerous social issues arise considering the role of society on eliminating HIV-AIDS since the appearance of the syndrome has revealed an undercurrent of hostility and rage (Figure 1). This article focuses mainly on the potential and catalytic role of stigma, the darkest facet of AIDS, and examines the major effects on childbearing subjects and the role society must play in order to eliminate HIV discrimination.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the interactions among main social issues.

Society’s role and the effects of stigma

Sexuality has long been a taboo subject, but it has undergone sweeping changes over centuries. On top of that, the emergence of HIV-AIDS has overwhelmed the entire world. The specific issue of AIDS is definitely a problem that has no short-term solution.7–9

Since the beginning of human existence, people have created the feeling of teamwork, formed tribes and communities, moved from place to place together, and lived in structured societies with rules of mutual respect. Illiterate people lacking the ability to navigate, lacking the wheel, or knowledge of the stars, and living a simple existence ended up creating enormous civilizations with incredible technological innovations. Despite this, technological innovations, illiteracy, racial discrimination, and economic exploitation have resulted in a major and unjustified worldwide crisis. Uneducated people can neither vote in elections nor satisfy their basic needs.

The role of women

Throughout the centuries, women have been mistreated and socially disadvantaged, living in the shadows, especially in Third World countries. The reason for this isolation is derived from sex-based distinction of difference in physique, established since antiquity.6 The HIV infection, in addition to all the insecurity, anxiety, and fear of discrimination derived from sex-based distinction, has led people – especially women – to avoid disclosing their HIV status to anyone but their family, a globally observed phenomenon. HIV infection is associated with minorities, marginalized, racially, ethnically, or sexually differentiated groups of people. Very frequently, once women are infected, they may be rejected even by their own families. The isolation, living a life entirely different from the rest of the people, creates a remarkable degree of tension. Protection of human rights is a vital prerequisite for eliminating all types of discrimination enforced on the HIV carriers and their families and friends. These facts make information and education regarding HIV infection imperative, so that the existing stereotypes and misconceptions can be corrected.10–12

Accessibility to therapy

Although there is no legal requirement for a doctor to treat any patient, fear of infection is not an ethically correct excuse for a doctor to deny therapy to an HIV-positive patient. Actions such as refusing to provide medical support and treatment to childbearing women are a major insult to human dignity.13,14 But it is not only the therapists who are responsible for the lack of health provision in pregnant women; it is commonly known that a pregnant woman at high risk, even for HIV infection, is not obliged to be tested or treated against her will, even if the fetus could be adversely affected by such a decision. Therefore, it is extremely important for patients to understand the necessity of seeking help, since there is a strong correlation between physical and psychological illness. Statistics show that morbidity and mortality rates are much higher in patients who require psychiatric attention.15–17

In AIDS-related medical and social situations, the right to free oneself from discrimination has received great attention. Stigma is a multifaceted social structure that has its own pathway; it starts with labeling, separation, status loss, and ends up in discrimination. It is known that the impact of vulnerability and sensitivity to stigma differ from person to person. The main goal of modern medicine is to eliminate stigmatization and discrimination and to ensure confidentiality in testing and counselling.18–20

Transmission and discrimination in modern societies

In Western societies, where an excellent physical appearance combined with a perfect physique is considered ideal, the opposite is regarded as antisocial and off-putting. Societies have been changeable over time, marginalizing the mentally ill, stigmatizing them to a great extent.21 A chronically ill or permanently impaired person is likely to be rejected by others, experiencing feelings of guilt and responsibility for being sick. In such a setting, women regarded as HIV patients are typically held responsible for their condition and, therefore, the stigma is almost inevitable, threatening their social expectations, ambitions, and progress; women have nothing to expect but barbarity.22 For this reason, childbearing women who are experiencing long-term stigmatizing problems have to form their own strategies to deal with societal denigration and mistreatment.23–25

It is a fact that the HIV virus is primarily contracted through sexual contact, breast-feeding, pregnancy, and exposure to any type of infected medical equipment.26 It is frequently transmitted through actions that are kept secret, hidden, or are illegal – a characteristic that makes this disease unique. Misconceptions have shaped beliefs; unfortunately, most people in our society do not realize that it is not the patient’s intention to be infected by HIV. Consequently, despair, exhaustion, and helplessness approaching panic are experienced by most female patients, who are faced with society’s rejection, losing their hopes for a prosperous future.27,28 It is almost impossible to conceptualize the degree of suffering the human body undergoes and the despair of the human mind in a societal group devastated by AIDS. Infected individuals are considered to be incapable of functioning normally, and in severe cases, they are forced to withdraw from occupational responsibilities. To a significant extent, they are perceived as threats, they face long-term, damaging degradation of their life style and, additionally, they have to cope with the everlasting stigma.27–30

Being stigmatized and restriction of opportunities on different levels invariably accompanies chronic diseases, resulting in a period of prolonged erosion of vocations and beliefs. Societies have constantly struggled to define discrimination and achievement. Nowadays, social stigma could have been eliminated with the use of modern technology but something like that is far away from reality. Since stigma exists and people are marginalized, subjects afflicted with AIDS are expected to struggle harder to achieve in society, facing great difficulties while reaching occupational independence and success. More specifically, HIV-positive women are neglected, less socially noticeable, meaning that their rehabilitation and long-term future are given less consideration. These women are offered limited opportunities, no aspirations, and worst of all, have no prospects regarding their general societal status. Uncertainty becomes a big part of their life.31–33

Living with HIV: social support and quality of life (QoL) in HIV-positive women

From the time of conception, the human organism maintains its integrity and stability through a range of cells and tissues, in a delicate cooperation with a complex network of regulatory mechanisms. Humans have adapted to difficult situations, encountered and eliminate dangerous diseases through time, many with the use of advanced knowledge and technology.34

According to WHO, 17.4 million women were living with HIV worldwide in 2014 constituting 51% of all adults living with HIV.35 Fortunately, from 2001 to 2013, the annual number of new HIV infections has declined by 38% globally, followed by a significant decline in AIDS-related deaths.

As previously discussed, pregnant women with HIV infection are usually disgraced, stigmatized, and discriminated because of their condition. However, gestation represents the highest personal and social value that should be protected and preserved. It is, therefore, society’s responsibility to identify and eliminate biases, not only in the general population, but also in clinical settings, so that all sick individuals are respected and cared for, regardless of race, religion, gender, nationality, or condition.36–38 The ideal approach to enforcing social support is to envision it as having both a practical and an emotional dimension. Emotional support plays an extremely important role in the lives of these people suffering from long-term diseases. The significance of emotional support is evident in studies that show a strong correlation between lack of support even between people with normal mental state.25,27,39–41

QoL refers to the personal satisfaction expressed or experienced by individuals regarding their physical, mental, and social status. It can be defined as a multidimensional notion that involves a satisfactory social status and role, physical well-being, intellectual functioning in a stable, healthy, emotional environment, as well as a grounded self-esteem.42 People living with AIDS are discredited, considering their lives so diminished that they no longer that life is worth living. Thus, the ethical task is to figure out how to approach this growing sociomedical issue. The medical profession is the area where the problem is most evident, and it is an area requiring special learning and training, based on oaths and codes of ethics. Since women remain unaware about AIDS and its spectrum, it is our responsibility as doctors to concern ourselves with improving their QoL.43–46

The role of medicine

The medical profession has traditionally (and inaccurately) reinforced a gender stereotype by looking upon women as the weaker sex in biological terms.6 This approach should be corrected, and various support programs should be structured and introduced in such a way so as to mobilize and inspire the entire society, and especially the young people, to build a new, more humane society that will respect all human beings. Governments and medical professionals should provide all the necessary resources and guidance and commit themselves to supporting HIV-positive women, combat ignorance and stigmatization, and reduce the widespread poverty that accompanies their condition. Besides access to multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, and participatory programs and the strengthening of basic health care, government officials should go beyond medical science. They should investigate the denigration of women worldwide, as well as the economic disintegration in many countries that prevents childbearing women from getting adequate infrastructure and effective antiretroviral therapies.47–51

Confidentiality of medical information

The sensitive personal information disclosed by the patient to a physician may frequently be of interest to parties outside the medical profession. However, this information has been traditionally, ethically, and legally guarded by confidentiality. Medical ethics bases this duty on the obligation to respect the patient’s privacy and autonomy, as well as on the need for loyalty and trust on the part of the physician.52 Nevertheless, confidentiality has been treated rather superficially and carelessly in modern medical practice. It is true that computerization of medical records enhances statistical analysis and facilitates administrative tasks. However, nowadays, with all the technological progress, malevolent and unauthorized personnel are allowed to have access and reveal medical information. Confidentiality is undoubtedly an unwritten ethical obligation. Physicians who carry the responsibility to protect their patients must be familiar with the regulations and policies so as to safeguard the patient’s medical information. Prevention is better than cure; therefore, expert advice, support, and education should be provided to safeguard medical identity.44,46,53–57

Current international approach and results

Lack of a clearly defined approach of stigma prevents experienced personnel from introducing efficient treatment programs and new initiatives with the final aim of annihilating discrimination. The stigma carries the inherent identity of dividing people into groups.

Literature reveals numerous survey methodologies and interviews of people living with AIDS or of the general population, both emphasizing their experience of HIV stigma, on access to prevention, treatment, and care, with a very small part of the articles referring to the need to create valid and reliable measures on evaluating the stigma through psychological tests and methods to eliminate it.58–60 However, due to the nature of the aforementioned social stigma, evaluating and practical measuring of the multifaceted stigma have proven to be significantly difficult. It is evident and profound that not many methods have been introduced into health care systems for a direct measurement of the HIV-related stigma and its cognate parameters. Since socioeconomical issues are the main predisposing factors of low educational level and lack of university/social program funding, these methods are marginalized. The economic difficulties complicate data collection of the infected population, the governments avoid investing in the appropriate information of the citizens, and lack of adequate health support is dominating.58–60

The global HIV–AIDS response reported a great rise of the people infected with AIDS in the last few years, but a reduction of the newly infected and the people dying from HIV.61 This has to do not only with the new facilities providing therapy and the more people receiving it but also due to the increased information on the issue of pregnant women with HIV. Therefore, more women are tested and eventually receive therapy to avoid mother-to-child transition. These are the results of the difficult efforts of World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund, and The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, in collaboration with national and international partners, to monitor key components of the health sector response to the HIV epidemic.61

The basis of mass-media interventions is one of the main solutions on reducing stigma. The design of stigma elimination methods relies on behavior and social attitude. Electronic mass communication media, aimed at a wide audience, is a very efficient means of introducing new ideas, beliefs, and updated knowledge on AIDS through continuous and repetitive electronic messages. Digital technology and cultural exposure combined with the subject’s personal experiences can have a significant effect on people and society itself.

Prevention and possible solutions to eliminate the HIV stigma

The first and undisputable step in HIV prevention is the introduction of the childbearer’s HIV testing. Many subjects do not join group testing due to the fear of stigmatization and family rejection while the problem is promoted by the everlasting stigma. Infected people might feel inferior to others if it is disclosed that they have tested positive, they are inherently fragile, prone to panic and run, a dangerous situation not so much because of the damage they do to individuals, but due to being vulnerable to explosive emotions of anger, depression and anxiety that lead them to negative thoughts. The problem ends up being a vicious cycle.62–64

In a world of changing societies, increasing poverty problems, governmental conflicts, inequality as main parts of the main social problems, the HIV–AIDS stigma remains rooted. Although the main reasons for this stigma remain unclear, it is commonly accepted that they originate from within the core of society. The social stigma is a pervasive problem regarding the attempts of HIV prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. The social stigma is a pervasive problem regarding the attempts of HIV prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. People need to have access to prognosis, diagnosis, and treatment. The government, in accordance with institutions and communities, needs to create programs involving contacting people, providing legal interventions, training programs, self-help and support groups, homecare teams, rehabilitation programs, and educational projects so as not only to accept and help people living with AIDS but also to spread the idea of prevention. Assessment of the stigma elimination within a social group suggests the allocation of projects and the use of reliable parameters and mechanisms within the affected groups. Literacy is of vital importance in the battle against HIV–AIDS stigma annihilation. The presentation of facts on AIDS is a good start. It is important to take into consideration the fact that such research programs are limited by the small size of samples. Social lives are devastated and patients avoid participating in research projects. A new generation of analysts, an exceptional network of policymakers, thinkers, leaders, and scholars who fully acknowledge the range of the stigma, needs to be recruited to reverse this phenomenon. In addition, nongovernmental organizations, philanthropic groups, and individual donors, with the help of digital technology and media, interested in the future of our society need to have the appropriate support for their valuable effort of eliminating the stigma.58

The need for adequate public health care

The principle that human beings are entitled to adequate health care is found in various international documents. These reports focus on the role of nondiscrimination attitudes and behaviors in propagating and shielding the right to protect oneself against malnutrition, extreme weather conditions, and lack of basic health care conditions that could potentially cause high morbidity and mortality rates; it is a matter of life and death.7–9

An inadequate standard of living is a threat to people with an immunocompromising comorbidity, such as HIV infection. A person with AIDS who lacks decent shelter, clothing, food, especially due to lack of health care access, will definitely face more difficulty even common diseases. Although health care is considered to be a basic human right in a civilized society, a good number of infected women live in poverty, experiencing high levels of stress caused by fatigue, fear, and lack of self-esteem, and have minimal access to the most fundamental health care services guaranteed and secured by every nation’s constitution. As a result, stigmatized women report depression, irritability, insomnia, and nervousness; it is a cluster of factors that creates extreme tension.11,13–14

As we have already discussed, mental health is the core of a healthy self-esteem. However, segregation, isolation, and other restrictions attached to the HIV status may trigger unjustified soaring discrimination. Combined with other stigmatizing conditions, several negative characteristics are attributed to pregnant women with HIV. These women are improperly blamed as the main hosts and the basic transmitters of the virus to other people and their children. Public health is the result of collaboration between society and science on preventing disease and promoting health and safety for people, guided by epidemiological data.65 However, the systematic maltreatment of women, in addition to slaughter and banishment of ethnic groups in Eastern Europe and Africa, demonstrates the abuse of human rights and the difficulty for public health to predominate. Medico-legal experts should focus on self-knowledge, self-improvement, social reform, and peace of mind.7–11

Stigma has a very true historical foundation. The increasing fragility of the social bonding has destabilized the social structure. All diseases possess a certain degree of a potentially active social stigma, which threatens social and personal interactions. In Western societies, where individual effort and achievement are highly valued, people suffering from permanent disabilities are frequently less likely to succeed, isolated in a dependent and weak position, and criminalized and negatively evaluated.66 For example, different types of physical deformities denote weakness in a world where physical strength and appearance are glorified. Being sick is both an individual experience and a social norm. Patients experience panic, discomfort, disorientation, and marginalization. The HIV-AIDS pandemic has caused enormous suffering throughout the world and presents a major challenge to society. It is society’s duty to accurately follow the development of the citizens, put an end to suffering, and eventually allow women to reengage organized social groups and structures. In times of rapid changes, where the world is more predictable than usual, subjects and organizations should be given the ability to innovate. One basic axiom should govern allowance of flexibility, instead of constraint enforcement. A radical societal reshaping will ultimately protect the vulnerable.

Discussion

As it was previously discussed, stigma devalues and diminishes the dignity of people who are subjected to it. Although HIV-AIDS has only been around for 40 years, its stigma is prominent and needs to be addressed and corrected, since the inevitable social consequences of being stigmatized lead to severely reduced opportunities, discrimination, and even rejection. One of the tragic consequences of discrimination is that it has a deep impact on vulnerable and sensitive groups. Discrimination against women in male-dominated societies can fundamentally threaten their social, economic, and family positions. Unfortunately, not too much progress has been made in annihilating the stigma throughout the years. Some years into the epidemic with no effective vaccine or permanent HIV cure, no solution has been given to the affected pregnant women that end up isolated. Discrimination and rejection guide people’s lives, associating this stigma with prolonged and severe psychological trauma. Stigma and discrimination are strong parameters in creating a hidden society that is extremely difficult to reach and reveal – a society governed by its own unique rules. Although striking differences in culture, mentality, social perspectives, language, and history of human rights exist within the societies, a total front should be created against the AIDS pandemic. Governments should review existing laws and enforce new ones that will repeal these legal frames that support discrimination.

The value of personal autonomy is deeply ingrained in our civilization; it is the intrinsic moral right of a person to follow their own plan, thoughts, and goals in life. The fight against HIV-AIDS should, therefore, aim towards women’s empowerment and decisive moves for solutions by society. Society should dare to attempt a shift in strategy with or without support from the governments. Only then, the stigma will be eliminated. HIV-positive women must be embraced as respected and indispensable members of our society.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all residents and staff at Democritus University of Thrace - Department of Medicine.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Lapointe N, Michaud J, Pekovic D, Chausseau JP, Dupuy JM. Transplacental transmission of HTLV-III virus. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(20):1325–1326. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198505163122012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Semprini AE, Vucetich A, Pardi G, Cossu MM. HIV infection and AIDS in newborn babies of mothers positive for HIV antibody. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987;294(6572):610. doi: 10.1136/bmj.294.6572.610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marte C, Anastos K. Women-the missing persons in the AIDS epidemic. Part II. Health PAC Bull. 1989;20(1):11–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simbayi LC, Kalichman S, Strebel A, Cloete A, Henda N, Mqeketo A. Internalized stigma, discrimination, and depression among men and women living with HIV/AIDS in Cape Town, South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(9):1823–1831. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar RM, Uduman SA, Khurrana AK. Impact of pregnancy on maternal AIDS. J Reprod Med. 1997;42(7):429–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooperman NA, Simoni JM. Suicidal ideation and attempted suicide among women living with HIV/AIDS. J Behav Med. 2005;28(2):149–156. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-3664-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall AJ. Public health trials in West Africa: logistics and ethics. IRB. 1989;11(5):8–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gostin LO. Health information privacy. Cornell L Rev. 1995;80:101–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gostin LO, Lazzarini Z, Neslund VS, Osterholm MT. The public health information infrastructure. A national review of health information privacy. JAMA. 1996;275(24):1921–1927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Craft MS, Delaney OR, Bautista TD, Serovich MJ. Pregnancy decisions among women with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(6):927–935. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9219-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orza L, Bewley S, Logie C, et al. How does living with HIV impact on women’s mental health? Voices from a global survey. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(Suppl 5):20289. doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.6.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Onono M, Kwena Z, Turan J, Bukusi EA, Cohen CR, Gray GE. You know you are sick, Why do you carry a pregnancy again? Applying the socio-ecological model to understand barriers to PMTCT service utilization in western Kenya. J AIDS Clin Res. 2015;6(6):467. doi: 10.4172/2155-6113.1000467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Bruyn M. Women, reproductive rights, and HIV/AIDS: issues on which research and interventions are still needed. J Health Popul Nutr. 2006;24(4):413–425. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kotzé M, Visser M, Makin J, Sikkema K, Forsyth B. Psychosocial factors associated with coping among women recently diagnosed HIV-positive during pregnancy. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(2):498–507. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0379-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohler PK, Ondenge K, Mills LA, et al. Shame, guilt, and stress: community perceptions of barriers to engaging in prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) programs in western Kenya. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2014;28(12):643–651. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toska E, Cluver DL, Hodes R, Kidia K. Sex and secrecy: how HIV-status disclosure affects safe sex among HIV-positive adolescents. AIDS Care. 2015;27(Suppl 1):47–58. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1071775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Enimil A, Nugent N, Amoah, et al. Quality of life among Ghanaian adolescents living with perinatally acquired HIV: a mixed methods study. AIDS Care. 2016;28(4):460–464. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1114997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pourmarzi D, Khoramirad A, Tehran HA, Abedini Z. Validity and reliability of Persian version of HIV/AIDS-related stigma scale for people living with HIV/AIDS in Iran. J Family Reprod Health. 2015;9(4):164–171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang CH, Li X, Liou Y, et al. Stigma against people living with HIV/AIDS in China: does the route of infection matter? PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0151078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meier BM, Gelpi A, Kavanagh MM, Forman L, Amon JJ. Employing human rights frameworks to realize access to an HIV cure. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18:20305. doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.1.20305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corrigan PW, Druss BG, Perlick DA. The impact of mental illness stigma on seeking and participating in mental health care. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2014;15(2):37–70. doi: 10.1177/1529100614531398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook RJ, Dickens BM. Reducing stigma in reproductive health. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2014;125(1):89–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mkwanazi NB, Rochat TJ, Bland RM. Living with HIV, disclosure patterns and partnerships a decade after the introduction of HIV programmes in rural South Africa. AIDS Care. 2015;27(1):65–72. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1028881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brickley DB, Hanh DLD, Nguyet LT, Mandel JS, Giang LT, Sohn AH. Community, family and partner-related stigma experienced by pregnant and postpartum women with HIV in Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(6):1197–1204. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9501-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van der Geest S. Wisdom and counselling: a note on advising people with HIV/AIDS in Ghana. Afr J AIDS Res. 2015;14(3):255–264. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2015.1055580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fatti G, Shaikh N, Eley B, Grimwood A. Effectiveness of community-based support for pregnant women living with HIV: a cohort study in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2016;28(Suppl 1):114–118. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1148112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rahangdale L, Banandur P, Sreenivas A, Turan J, Washington R, Cohen CR. Stigma as experienced by women accessing prevention of parent to child transmission of HIV services in Karnataka, India. AIDS Care. 2010;22(7):836–842. doi: 10.1080/09540120903499212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li MJ, Murray JK, Suwanteerangkul J, Wiwatanadate P. Stigma, social support, and treatment adherence among HIV-positive patients in Chiang Mai, Thailand. AIDS Educ Prev. 2014;26(5):471–483. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2014.26.5.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orza L, Bewley S, Chung C, et al. “Violence. Enough already”: findings from a global participatory survey among women living with HIV. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(Suppl 5):20285. doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.6.20285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alum AC, Kizza B, Osingada CP, Katende G, Kaye DK. Factors associated with early resumption of sexual intercourse among postnatal women in Uganda. Reprod Health. 2015;12:107. doi: 10.1186/s12978-015-0089-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strathdee SA, West BS, Reed E, Moazan B, Azim T, Dolan K. Substance Use and HIV among female sex workers and female prisoners: risk environments and implications for prevention, treatment, and policies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(Suppl 2):S110–S117. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mukolo A, Torres I, Bechtel RM, Sidat M, Vergara AE. Consensus on context-specific strategies for reducing the stigma of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in Zambézia Province, Mozambique. SAHARA J. 2013;10(3–4):119–130. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2014.885847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Csete J, Pearshouse R, Symington A. Vertical HIV transmission should be excluded from criminal prosecution. Reprod Health Matters. 2009;17(34):154–162. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(09)34468-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lenarsky M, Parr RL, Seanor HE. Epidemic poliomyelitis: Review of Five Hundred Twenty-Six Cases. Am J Dis Child. 1951;82(2):160–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Organization Number of women living with HIV. 2014. [Accessed April 20, 2017]. Available from: http://www.who.int/gho/hiv/epidemic_status/cases_adults_women_children/en/

- 36.Shapiro R, Dryden-Peterson S, Powis K, Zash R, Lockman S. Hidden in plain sight: HIV, antiretrovirals, and stillbirths. Lancet. 2016;387(10032):1994–1995. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30459-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rael CT, Hampanda K. Understanding internalized HIV/AIDS-related stigmas in the Dominican Republic: a short report. AIDS Care. 2016;28(3):319–324. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1095277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joshi S, Kulkarni V, Gangakhedkar R, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a repeat HIV test in pregnancy in India. BMJ Open. 2015;5(6):e006718. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wood BR, Ballenger C, Stekler JD. Arguments for and against HIV self-testing. HIV AIDS (Auckl) 2014;6:117–126. doi: 10.2147/HIV.S49083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Madzimbamuto FD, Ray S, Mogobe KD. Integration of HIV care into maternal health services: a crucial change required in improving quality of obstetric care in countries with high HIV prevalence. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2013;13:27. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-13-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mofenson LM. Antiretroviral therapy and adverse pregnancy outcome: the elephant in the room? J Infect Dis. 2016;213(7):1051–1054. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schalock RL. (ed.)1997Quality of Life, Vol. 2 Application to Persons with Disabilities Washington, USA: American Association on Mental Retardation [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paudel V, Baral KP. Women living with HIV/AIDS (WLHA) battling stigma, discrimination and denial and the role of support groups as a coping strategy: a review of literature. Reprod Health. 2015;12:53. doi: 10.1186/s12978-015-0032-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Makin JD, Forsyth BWC, Visser MJ, Sikkema KJ, Neufeld S, Jeffery B. Factors affecting disclosure in South African HIV-positive pregnant women. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22(11):907–916. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Too W, Watson M, Harding R, Seymour J. Living with AIDS in Uganda: a qualitative study of patients’ and families’ experiences following referral to hospice. BMC Palliat Care. 2015;14:67. doi: 10.1186/s12904-015-0066-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mahajan AP, Sayles JN, Patel VA, et al. Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: a review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS. 2008;22(Suppl 2):S67–S79. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000327438.13291.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaljee LM, Green M, Riel R, Lerdboon P, Minh TT. Sexual stigma, sexual behaviors and abstinence among Vietnamese adolescents: implications for risk and protective behaviors for HIV, STIs, and unwanted pregnancy. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2007;18(2):48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turan JM, Bukusi EA, Onono M, Holzemer WL, Miller S, Cohen CR. HIV/AIDS stigma and refusal of HIV testing among pregnant women in rural Kenya: results from the MAMAS study. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(6):1111–1120. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9798-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taft TH, Keefer L. A systematic review of disease-related stigmatization in patients living with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016;9:49–58. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S83533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mkwanazi NB, Rochat TJ, Bland RM. Living with HIV, disclosure patterns and partnerships a decade after the introduction of HIV programmes in rural South Africa. AIDS Care. 2015;27(Suppl 1):65–72. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1028881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coleman JD, Tate AD, Gaddist B, White J. Social determinants of HIV-related stigma in faith-based organizations. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(3):492–496. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Siegler M. Confidentiality in medicine—a decrepit concept. N Engl J Med. 1982;307(24):1518–1521. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198212093072411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Treves-Kagan S, Steward WT, Ntswane L, et al. Why increasing availability of ART is not enough: a rapid, community-based study on how HIV-related stigma impacts engagement to care in rural South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:87. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2753-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fakoya I, Reynolds R, Caswell G, Shiripinda I. Barriers to HIV testing for migrant black Africans in Western Europe. HIV Med. 2008;9(Suppl 2):23–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reynes-Estrada M, Varas-Diaz N, Martinez-Sarson MT. Religion and HIV/AIDS stigma: considerations for the nursing profession. New School Psychol Bull. 2015;12(1):48–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Azim T, Bontell I, Strathdee SA. Women drugs and HIV. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(Suppl 1):S16–S21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gökengin D, Doroudi F, Tohme J, Collins B, Madani N. HIV/AIDS: trends in the Middle East and North Africa region. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;44:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Heijnders M, Van Der Meij S. The fight against stigma: an overview of stigma-reduction strategies and interventions. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11(3):353–363. doi: 10.1080/13548500600595327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brown L, Macintyre K, Trujillo L. Interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma: what have we learned? AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15(1):49–69. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.1.49.23844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ehiri JE, Anyanwu EC, Donath E, Kanu I, Jolly PE. AIDS-related stigma in sub-Saharan Africa: its contexts and potential intervention strategies. AIDS Public Policy J. 2004;20(1–2):25–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Global Hiv/Aids Response - Epidemic update and health sector progress towards Universal Access - Progress Report. 2011. [Accessed April 11, 2017]. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/progressreports/en/2017.

- 62.Webber GC. Chinese health care providers’ attitudes about HIV: a review. AIDS Care. 2007;19(5):685–691. doi: 10.1080/09540120601084340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Abell N, Rutledge SE, McCann TJ, Padmore J. Examining HIV/AIDS provider stigma: assessing regional concerns in the islands of the Eastern Caribbean. AIDS Care. 2007;19(2):242–247. doi: 10.1080/09540120600774297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Abadía-Barrero CE, Castro A. Experiences of stigma and access to HAART in children and adolescents living with HIV/AIDS in Brazil. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(5):1219–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marmot M, Bell R. Fair society, healthy lives. Public Health. 2012;126:S4–S10. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gannon B, Nolan B. The impact of disability transitions on social inclusion. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(7):1425–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]