Abstract

We are the first to report a case of severe broad nose deformity caused by radical surgery on the maxillary sinus in childhood. We treated this broad nose deformity with closed rhinoplasty.

Keywords: Broad nose, maxillary sinus, radical surgery, nasal osteotomy

Introduction

Broad nose deformity during childhood is usually associated with various congenital diseases (e.g. facial cleft, meningocele and craniosynostosis) [1–4]. In general, trauma causes broad nose deformity [5].

We report a case of broad nose deformity caused by radical surgery on the maxillary sinus in childhood. Chronic sinusitis is a common disease in children for which radical surgeries on the maxillary sinus had previously been performed [6]. However, to the best of our knowledge, broad nose deformity caused by surgery on the maxillary sinus has never previously been reported. In our case, the patient had no nasal deformities until he underwent the surgery at 6 years of age. In addition, there were no congenital diseases or trauma that leads to the deformity. From his clinical course, it was believed that maxillary sinus surgery was the cause of the broad nose deformity. The patient was treated with closed rhinoplasty, and good results were obtained following a relatively simple operation.

Case report

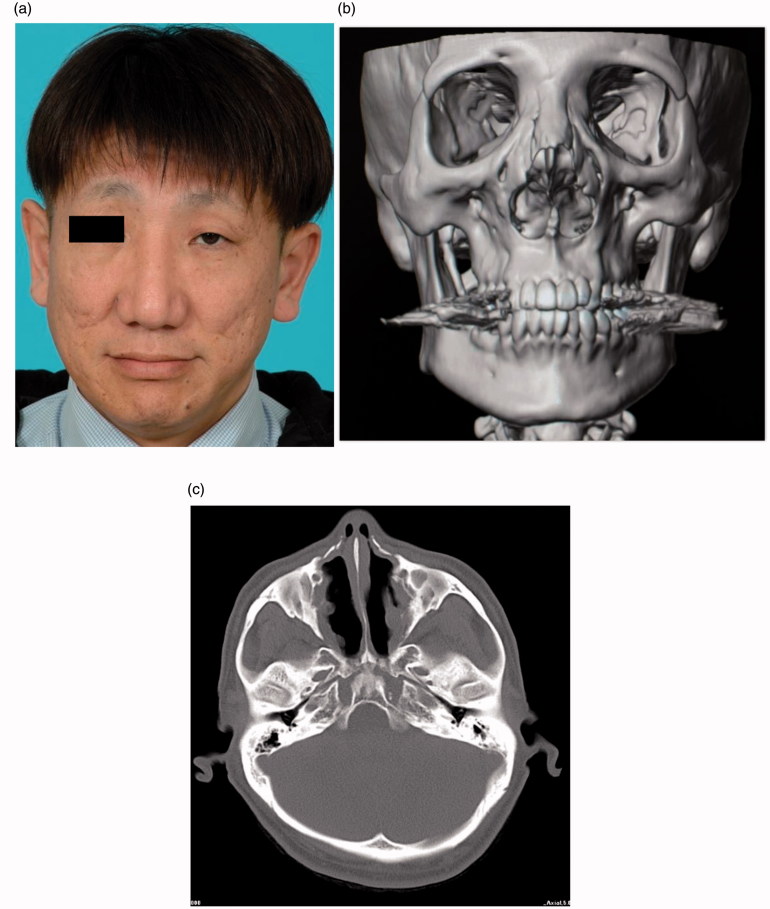

The subject was a 46-year-old male who had undergone surgery to the maxillary sinusitis at 6 years of age. Subsequently, broad nose deformity gradually appeared, and it worsened as he matured. The patient had become concerned about this deformity, so he visited our clinic. Significant broad nose deformity was evident, and the computed tomography (CT) images (Figure 1) revealed a collapsed maxillary sinus and a prominent expansion of the nasal cavity and piriform aperture. The patient had no abnormalities of the nose until after the first surgery. Furthermore, there were no congenital diseases or trauma that could have lead to nasal deformity. Therefore, we concluded that the deformity had resulted from this surgery. We decided to treat the deformity with closed rhinoplasty using medial-oblique osteotomies, low-curved lateral osteotomies and multiple lateral osteotomies [3]. Because of the severely expanded piriform aperture, narrowing rhinoplasty with a single lateral osteotomy would have created a large bone gap at the osteotomy site that would have eventually lead to relapse. Due to this concern, we decided to use multiple lateral osteotomies on the nasal sidewall in addition to the low-curved lateral osteotomies and the medial-oblique osteotomies (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Pre-operative view (a), 3D-CT image (b), axial CT image (c). Prominent broad nose deformity was identified and shrinkage of maxillary sinus and prominent expansion of nasal cavity and piriform aperture can be seen.

Figure 2.

Osteotomy lines. Central V lines: medial-oblique osteotomies. Most outside lines: low-curved lateral osteotomies. Lines between them: multiple lateral osteotomies.

All osteotomies were performed from an inter-cartilaginous (IC) incision and cheek stab-incision using a micro-osteotome. The planned osteotomies are shown in Figure 2. Pushing the skin over the nasal sidewall achieved the complete fractures and a narrowing of the nasal vault. The operative time was about an hour, and there was only a small amount of bleeding. After the surgery, a full-time lateral nasal splint was used for 6 weeks, followed by a night-only splint for 6 months. The results can be seen in Figure 3. The post-operative nose was aesthetically improved, and no recurrence was observed.

Figure 3.

Post-operative view (a), 3D-CT image (b), axial CT image (c) at 1 year after the surgery. The post-operative nose was aesthetically excellent and shrinkage of maxillary sinus and prominent expansion of nasal cavity and piriform aperture were improved.

Discussion

A broad nose is wider and larger than the average nose. The official US Government definition of a rare disease is one that affects 200,000 people or fewer [4]. Broad nose deformity during childhood is usually associated with various congenital diseases (e.g. facial cleft, meningocele, craniosynostosis and trisomy 8) [1–4]. Chronic sinusitis is a very common disease in childhood for which conservative treatment is generally selected in paediatric patients [6]. Prior to the 1980s, when endoscopic surgery became popular, maxillary sinus surgery was often performed in cases where the conservative course proved ineffective. Our patient underwent surgery to his maxillary sinusitis at 6 years old in the 1970s.

As for maxillary growth, it is generally considered to develop rapidly during early school years. The patient in this case had undergone surgery during this critical period. It has been reported that the size of the maxillary sinus is remarkably reduced after undergoing radical surgery, healing with the proliferation of connective and scar tissue, according to Hajek [7] or with proliferation of scar tissue and bones, according to Tonndorf [8]. In addition, Iinuma et al. reported a case in which the upper wall of the maxillary sinus dropped inside the maxillary sinus [9]. The reasons listed for these undesirable outcomes are as follows: (1) Traction by scar tissue in the maxillary sinus, (2) surgical removal of the maxillary sinus wall, (3) pressure imposed by tissues and (4) external force by muscles of mastication [9]. They reported that the first reason was the major cause.

In our case, the inside of the maxillary sinus was filled with scar tissue resulting from the maxillary surgery. Additionally, the upper wall and the inner wall of the maxillary sinus in particular were tractioned during the course of growth. As a result, it was thought that the angle from the nose to the maxillary sinus had widened, leading to the wide nose deformation. As is evident in our patient, it is necessary to take sufficient care when performing an operation on the maxillary sinus of young patients. Because of our findings, we believe that there may be cases of wide nose deformity due to a similar cause in currently middle-aged patients. Considering the treatments for broad nose deformity, relapse is one of the main problems: the relapse occurs as a result of a conventional surgical approach due to the development of bony defects between the maxilla and the nasal bone. We therefore treated the broad nose by folding the convex nasal walls in the other direction, effectively turning the convex wall into a concave one. This method prevents bony defects and a subsequent relapse. One key benefit of this technique is to preserve periosteum continuity in order to maintain blood flow and support the bone fragments so that they do not shrink. Percutaneous low-curved lateral osteotomies using micro-osteotome from cheek stab incisions not only facilitate curved osteotomies, but also preserve periosteal and mucosal continuity [10].

This approach is also considered an excellent technique in terms of minimising bleeding. We believe this is the first report describing a severe broad nose deformity caused by radical surgery on the maxillary sinus in childhood, even though some authors have made mention of similar cases. We have also shown that an excellent clinical outcome can be achieved with closed rhinoplasty that includes multiple lateral osteotomies.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Kenji Yamaguchi.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Kenji Yamaguchi is PhD student, Department of Plastic surgery at Tohoku University of Japan.

Dr. Yoshimichi Imai is Associate Professor, Department of Plastic surgery at Tohoku University.

Dr. Akimichi Sato is PhD student, Department of Plastic surgery at Tohoku University.

Masahiro Tachi is Professor, Department of Plastic surgery at Tohoku University.

References

- 1. Mulliken JB. Bilateral complete cleft lip and nasal deformity: an anthropometric analysis of staged to synchronous repair. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:9–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tang Chen YB, Chen HC, Randall P.. Reconstruction of a compound facial deformity involving the columella, nasal base, and upper lip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87:950–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Posnick JC, Lin KY, Jhawar BJ, et al. Apert syndrome: quantitative assessment by CT scan of presenting deformity and surgical results after first-stage reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93:489–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Right Diagnosis from Healthgrades [Internet] [cited 2015 Aug 13]. Available from: http://www.rightdiagnosis.com [Google Scholar]

- 5. Narumi S. Rhinoplasty. Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 2011;54:157–167. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Majima Y. Treatment and effect of chronic paranasal sinusitis. Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 1996;39:85–88. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hajek M. Pathologic und Therapie derentzundlichen Erkrankungen der Nebenhohlen der Nase [Pathology and therapy of the inflammatory diseases of nasal sinus]. S. 254, 5te Auful. vol. 5 Leipizig: Deuticke; 1926:105–108. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tonndorf D. Beitrag zur Ausheilung dernach LucCaldwell operierten Kieferhohle [Contribution to healing of maxillary sinus by Luc-Caldwell operation.]. HNO-Heilk. 1929;22:54–59. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Iinuma T. Post-operation of maxillary sinus. Pract Otolaryngol. 1982;75:931–938. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Imai Y. Rhinoplasties with osteotomies: nose cosmetic surgery, PEPARS. Tokyo: All Japan Hospital Publishing Association; 2015;(No105):65–74. [Google Scholar]