Abstract

A randomized dietary intervention trial over 4 years examined diet, weight, and obesity incidence (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) differences between study groups. Participants were 1510 breast cancer survivors with BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 at entry. Dietary intake was assessed yearly by telephone; weight and height were measured at clinic visits. Intervention participants consumed more fruit, vegetables, and fiber, and less energy from fat than control participants during follow-up—cross-sectionally (p<.0001) and longitudinally (p<.0001); weight did not differ between study groups at any follow-up visit; significant weight change difference was observed between groups only in the first year (p<.0001). Diet and weight results remained unchanged after stratifying by age and BMI. No difference in obesity incidence was found during follow-up (p> 0.1) among overweight members of either study group. Without specific efforts to reduce total energy intake, dietary modification does not reduce obesity or result in long-term weight loss.

Keywords: Fruit, vegetables, total fiber, energy from fat, body weight, clinical trial

INTRODUCTION

As the prevalence of obesity among Americans continues to rise (Swinburn, Caterson, Seidell, & James, 2004) the impetus to promote weight loss among the overweight and obese is increasingly important, because obesity is associated with greater risk for chronic diseases, mortality (Calle, Rodriguez, Walker-Thurmond, & Thun, 2003), and psychological distress (Paeratakul, White, Williamson, Ryan, & Bray, 2002). Weight control is particularly of clinical relevance among breast cancer survivors, where co-morbidities such as elevated glucose, insulin, and cardiovascular diseases are common (Goodwin et al., 2002).

Manipulating dietary energy density has been an area of intensive interest: studies have examined replacing energy-dense high-fat food with fiber-rich food, such as fruit vegetables, and whole grains, as an approach to reduce the risk of both chronic disease and obesity (Rolls, Ello-Martin, & Tohill, 2004). Current data suggest that people typically eat a consistent amount (volume) of food on a day-to-day basis (Kral, Roe, & Rolls, 2002). Hence, reducing a dietary energy density should theoretically reduce total energy intake, which in turn should help maintain an energy balance that is favorable to weight loss. However, whether such dietary modification can promote weight loss in an ad-libitum conditions remains inconclusive: weight change among intervention participants in these studies range from ‘weight loss’(Howard et al., 2006; Lanza et al., 2001) to ‘no change’ (Rock et al., 2001) to ‘weight gain’ (Djuric et al., 2002). The variation in weight change observed was likely the product of variations in dietary intake and physical activity. But it is also possible that some of that variation was due to the difference in the age and body mass index (BMI) distribution of the participating cohorts. Current age and BMI are strong predictors of weight change during adulthood (Ball, Crawford, Ireland, & Hodge, 2003), yet none of these studies reported age and BMI specific results.

A number of large-scale cohort studies with long-term follow up data have suggested that a diet high in fruit and vegetables might reduce the incidence of obesity (He et al., 2004; Newby et al., 2003). The generalizability of clinical trials (Epstein et al., 2001; Singh, Niaz, & Ghosh, 1994) that reported similar findings is limited for a number of reasons, including restriction of energy intake in intervention participants, choice of a vegetarian population, and short duration of follow-up.

This report investigates dietary intake and body weight in a subgroup of participants in the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) Study, a large-scale clinical trial designed to test the effect of a diet high in vegetables, fruit, and fiber and low in fat on risk for recurrence and survival in women with a history of breast cancer. Energy intake and weight loss were not WHEL Study objectives. This report considers WHEL participants who were either overweight or obese at study entry, and investigates the relationship between dietary intake and body weight for up to 4 years of follow-up. This study compares the intervention and control groups at baseline and follow-up periods for the following variables (1) mean consumption of fruit and vegetables, fiber, and percent energy from fat, total energy intake, physical activity, as well as body weight; (2) mean dietary intakes and body weight after stratifying by baseline age and BMI, (3) changes in dietary intake and body weight, and (4) the incidence of obesity in overweight control and intervention group participants.

Materials and Methods

Population

This study investigates a subgroup of participants in the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) Study—a multi-site clinical trial designed to determine the efficacy of a dietary intervention on reducing breast cancer recurrence and death. The WHEL Study protocol has been described in detail elsewhere (Pierce et al., 2002).

WHEL Study participants who were either overweight (BMI=25–29.9 kg/m2) or obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) at baseline (n=1760) were eligible for inclusion in the present study. Of this sample, 250 participants (14%) lacked data on body weight beyond baseline because of recurrence, death, or voluntary non-participation. The present analyses considers the remaining 1510 women (control=760, intervention=750) for whom dietary intake and weight data were available at 4 years post-randomization.

Of 1510 women, 838 were overweight (BMI=25–29.9 kg/m2) at study entry (control=423, intervention=415), and formed the sample for examining obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) incidence during follow-up periods (years 1, 2 or 3, and 4).

Dietary assessment

Dietary intake was assessed through a set of four 24-hour dietary recalls. Trained dietary assessors conducted these recalls over the telephone on randomly selected days, stratified for weekend vs. weekdays, over a 3-week period. Dietary recalls were administered to the participants at study entry and then annually thereafter for 4 years (split sample (50%) at years 2 and 3). The Minnesota Nutritional Data System software was used to collect and estimate dietary intakes (NDS version 4.01, 2001, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN).

A number of strategies helped to maximize the accuracy of dietary recall data. Dietary assessors had completed a training program that included standardized data collection, proper interview technique, and efficient use of dietary analyses software. Participants were trained, before study enrollment, to estimate serving sizes with food models, measuring cups, and spoons, and were provided with two-dimensional food models for reference during recalls. In addition, NDS used a multi-pass method that improved recall accuracy by prompting assessors to obtain detail data about type, amount, and preparation method of food eaten.

Participants in the intervention group were encouraged to maintain a dietary pattern that included daily consumption of at least 5 vegetable servings, 16 ounces of vegetable juice (or equivalent vegetable servings), 3 fruit servings, 30 grams of fiber (18g/1000 kcal), and 15–20% energy from fat. Telephone counseling, monthly cooking classes and newsletters were the principal methods to promote dietary change in the intervention participants. Control group participants received print materials that included dietary guidelines from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDHHS, 1995) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI, 1995) and a bimonthly cohort maintenance newsletter that included general health and nutrition information unrelated to the intervention group’s dietary goal.

Exposure variables

Dietary intake servings were quantified as follows: (1) Intake of total fruit and vegetables (servings/day/1000kcal) – a vegetable serving was defined as ½ cup cut-up fresh or cooked vegetable or 1 cup raw leafy green vegetable or equivalent amounts provided by multi-ingredient dishes; a fruit serving was ½ cup of cut-up fresh or cooked fruit or ¼ cup of dried fruit or 1 medium piece fresh fruit; fruit juice, iceberg lettuce, white potatoes, and legumes were not included in the computation of daily total fruit and vegetable intake; (2) Intake of total fiber (grams/day/1000 kcal) – total fiber included both soluble and insoluble fiber; and (3) percent energy from fat/day – (energy obtained from daily intake of total fat / total daily energy intake) ×100.

Outcome variable

Weight and height were measured—with the participants wearing light clothing and no shoes—during clinic visits (baseline, years 1, 2 or 3, and 4) scheduled in the WHEL Study. BMI was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m2). A woman was considered obese if her BMI was ≥ 30 kg/m2.

Physical activity

Physical activity was determined using a 9-item measure from the Personal Habits questionnaire developed for Women’s Health Initiative (WHI, 1998), expressed as metabolic equivalents per week (MET-min/week), and completed at baseline and at follow-up visits. For the WHEL Study, this questionnaire was calibrated with the standard 7-Day Physical Activity Recall (PAR) and validated with an accelerometer reading (Johnson-Kozlow, Rock, Gilpin, Hollenbach, & Pierce, 2007).

Other variables

Information on age and stage of cancer at the time of diagnosis, and treatment modalities was obtained from patients’ medical records. Standard questionnaires administered at baseline ascertained demographic and weight history. BMI was categorized as overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2), obese class-I (30–34.9 kg/m2), and obese class-II (≥35 kg/m2). Other potential co-variables examined in this analysis included race/ethnicity, education, marital status, employment status, smoking status, alcohol intake, menstrual history, adult weight history (stable vs. not stable), and time elapsed between cancer diagnosis and study entry (in months).

Informed written consent from study participants was collected in the WHEL Study. The Human Subjects Committee of the University of California, San Diego, and all participating institutions approved the procedures for the present study.

Statistical Analyses

The control and the intervention group were compared for participants’ baseline characteristics to validate randomization. Demographic, behavioral, cancer, and treatment related variables, thought to be potential confounders of the relationship between dietary intake and weight, were examined in this respect.

Participants with missing weight data at all follow-up time points were identified and compared by study group for attrition frequency. Participants with missing data were also compared to participants with complete data on key variables such as age, BMI, and cancer stage.

Mean daily intake of fruit and vegetables, total fiber, and percent energy from fat, as well as mean body weight, were calculated and graphed for the control and intervention participants, both at baseline and at follow-up (years 1–4). Total caloric intake and physical activity were also calculated and compared between the study groups during the same points of time. Corresponding means at baseline and at specific follow-up times were compared against each other to discern group difference, if any. Daily total energy consumption was taken into account while calculating mean fruit and vegetable servings and total fiber intake. The same analyses were rerun after stratification by baseline age (<55 vs. ≥ 55 years) and BMI (overweight, obese class-I, and obese class-II). For stratified analyses, body weight at year 2 and 3 (split (50%) sample) were considered together to ensure adequate sample size.

Mixed effect models ascertained group by time interaction. Mixed effect models are the best option available for such analyses given the correlations among repeated measurements within a participant and the ability of this model to handle random missing values. To find a suitable covariance structure, correlations and variances over time were examined for each variable modeled. Although the correlation between any two time points varied little, and the variances over time remained steady, both of which favored compound symmetry as the choice of covariance structure, each model was run with the same fixed effect but different covariance structure such as toeplitz, unstructured, and autoregressive. ‘Unstructured’ covariance provided the smallest Akaike’s Criterion (AIC) value, and was used in the final mixed models.

Since a significant difference in weight change was observed between the control and intervention groups only in the first year of follow-up despite sustained dietary changes in the intervention group, secondary data analysis, using a linear regression model, was carried out to ascertain which dietary changes might be associated with weight change.

Finally, incidence of obesity at follow-up (years 1, 2 or 3, and 4) was calculated for those who were overweight at study entry, overall and by study group. The corresponding incidences of all specific follow-up visits were then compared by t-test to ascertain any difference by randomization status.

RESULTS

The mean age of the 1510 women who were either overweight or obese at baseline was 54.4 years (range 28–74 years, standard deviation [SD] = 9.0). The mean BMI was 30.9 (SD=5.2); 56% were overweight, 26% were obese class-I, and 18% were obese class-II. Although mostly non-Hispanic white (83%), the cohort also included a small but varied group of minority women (African American: 5%, Asian: 3%, Hispanic: 6%, and other ethnicities: <3%). Highly educated (48% college graduate) and predominantly employed (71%), 70% of the participants were also married. Fewer than 5% were diagnosed with stage IIIA cancer or were currently smoking. The mean energy intake was 1746 kcal/day (SD=426) and mean time between cancer diagnosis and study entry was 24.9 months (SD=12.2) (data not shown).

Comparison of demographic, behavioral, cancer, and treatment related characteristics between the control (n=760) and the intervention participants (n=750) showed that the randomization was successful. Tamoxifen use was marginally significantly higher in the intervention group (p=0.06) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics between the control and the intervention groups: The Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) Study; N=1510.

| Variables | Control (n=760) |

Intervention (n=750) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| mean ± sd | mean ± sd | ||

| Age (years) | 54.5 ± 8.4 | 54.4 ± 8.4 | 0.82 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 31.0 ± 5.5 | 30.7 ± 4.8 | 0.25 |

| % | % | ||

| Age categories | |||

| 20–44 | 12.5 | 11.3 | |

| 45–54 | 40.6 | 43.7 | 0.35 |

| 55–64 | 34.5 | 31.1 | |

| ≥ 65 | 12.4 | 13.9 | |

| Body mass index categories | |||

| 25–29.99 | 55.7 | 55.3 | |

| 30–34.99 | 24.7 | 27.5 | 0.32 |

| ≥ 35 | 19.6 | 17.2 | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 83.3 | 83.3 | |

| Black | 5.7 | 5.2 | |

| Asian | 2.1 | 2.9 | 0.86 |

| Hispanic | 6.3 | 5.9 | |

| Others | 2.6 | 2.7 | |

| Education (college graduate vs. non-graduate) | |||

| College graduate | 45.9 | 50.0 | 0.11 |

| Married (yes/no) | |||

| Yes | 70.0 | 69.6 | 0.87 |

| Employment (yes/no) | |||

| Yes | 70.7 | 70.6 | 0.95 |

| Smoking habit | |||

| Non smoker | 53.8 | 50.9 | |

| Past smoker | 48.5 | 51.5 | 0.45 |

| Current smoker | 4.5 | 4.1 | |

| Alcohol consumption | |||

| None | 33.2 | 33.5 | |

| 0–19 gm/d | 60.6 | 60.0 | 0.95 |

| ≥ 20 gm/d | 6.2 | 6.5 | |

| Menstrual history | |||

| Pre-menopausal | 7.8 | 9.6 | |

| Post-menopausal | 84.5 | 82.1 | 0.40 |

| Peri-menopausal | 7.8 | 8.3 | |

| Adult weight history (stable vs. unstable) | |||

| Stable | 8.2 | 10.0 | 0.21 |

| Stage of cancer | |||

| I | 40.1 | 37.7 | |

| II | 55.0 | 58.0 | 0.48 |

| IIIA | 4.9 | 4.3 | |

| Tamoxifen use | |||

| Never used | 33.6% | 29.1% | 0.06 |

| Using at study entry | 66.4% | 70.9% | |

| Time elapsed since cancer diagnosis | |||

| (months) | 25.3 ± 12.2 | 24.5 ± 12.2 | 0.20 |

Mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and frequency for categorical variables are presented

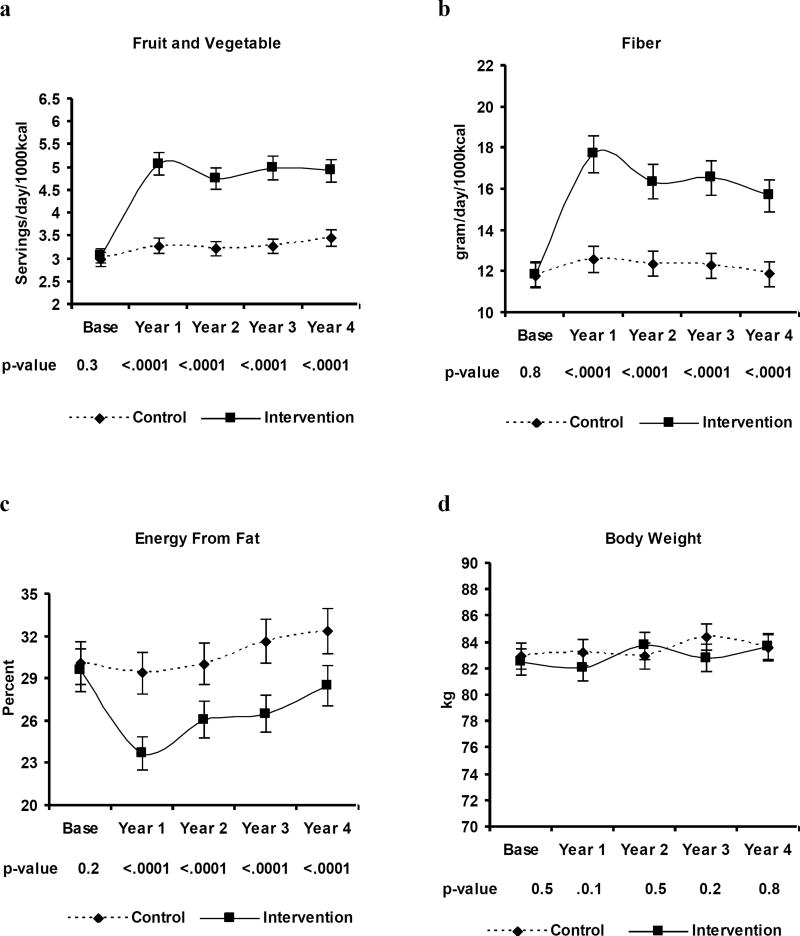

At baseline, consumption of fruit and vegetables, total fiber, and percent energy from fat was similar in both groups. The control group reported consuming approximately 5 servings of fruit and vegetables, 20 grams of fiber, and 30% energy from fat; these values remained relatively unchanged during follow-up. Intervention group participants were consuming significantly more fruit and vegetables, total fiber, and lower percent energy from fat during follow-up (p <0.0001) than they were at baseline (Figure 1a, 1b, and 1c). The study groups did not differ in their total caloric intake (kcal/day) at baseline (control = 1749 ± 16, intervention = 1743 ± 15, p = 0.65), at 1 year (control = 1592 ± 15, intervention = 1572 ± 13, p = 0.33), and at 2 year (control = 1596 ± 21, intervention = 1557 ± 19, p = 0.19) but differed slightly at 3 year (control = 1597 ± 22, intervention = 1500 ± 20, p = 0.002) and at 4 year (control = 1561 ± 16, intervention = 1513 ± 15, p = 0.03). The two groups also did not differ by physical activity (MET-min/week) at any of the study time points [control vs. intervention: baseline (775 ± 31 vs. 720 ± 30, p = 0.21), 1 year (834 ± 33 vs. 816 ± 33, p = 0.70), 2 year (787 ± 47 vs. 769 ± 51, p = 0.80), 3 year (855 ± 52 vs. 721 ± 44, p = 0.06), and 4 years (781 ± 33 vs. 779 ± 37, p = 0.97)] (data not shown). No difference in mean body weight was observed between the groups, either at baseline or at follow-up (Figure 1d).

Figure 1.

1a, 1b, 1c, and 1d

Mean consumption of fruit and vegetables, total fiber, and percent energy from fat and mean body weight in the control and in the intervention group over the study period: The Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) Study.

N=1510. Participants with baseline body mass index <25 kg/m2 or without weight data at all follow-up visits have been excluded.

The difference in mean dietary intakes between the study groups at follow-up remained significant, irrespective of baseline age and BMI categories, except for percent energy from fat in the obese class-II. In that category, percent energy from fat among the intervention participants declined significantly in the first year; but started to increase thereafter, and by the end of follow-up there was no difference between the groups. In the control group, mean weight increased monotonically with each follow-up measurement in younger women (<55 years, mean weight: 83.2 (base), 84.0 (year 1), 84.8(year 2/3), and 84.8(year 4)) and decreased in older women (≥55 years, mean weight: 82.7 (base), 82.4 (year 1), 82.3(year 2/3), and 82.1(year 4)). Among intervention participants, mean weight increased in younger women (<55 years, mean weight: 83.7 (base), 83.6 (year 1), 85.2 (year 2/3), and 85.6 (year 4)) and remained stable in older women (≥55 years, mean weight: 81.0 (base), 80.3 (year 1), 81.2 (year 2/3), and 81.5 (year 4)) by the end of follow-up (data not shown).

Significant differences were observed between the groups over time in their changes of reported fruit and vegetables, total fiber, and percent energy from fat intake (p for group by time interaction: <0.0001) (Table 2). Significant difference in change of body weight occurred between the groups in the first year of follow-up only (p for group by time interaction: 0.001), and not at subsequent follow-up times.

Table 2.

Longitudinal data analyses; the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) Study.

| Fruit & Vegetables (servings/day/1000kcal) |

Total Fiber (g/day/1000 kcal) |

Percent Energy from Fat |

Body Weight (kilogram) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| Group | ||||||||

| Int† | 0.09 | 0.33 | 0.06 | 0.77 | −0.49 | 0.16 | −0.46 | 0.55 |

| Time | ||||||||

| Year 1 | 0.30 | <.0001 | 0.81 | <.0001 | −0.68 | 0.02 | 0.35 | 0.04 |

| Year 2 | 0.26 | 0.002 | 0.45 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.002 |

| Year 3 | 0.26 | 0.002 | 0.51 | 0.01 | 1.45 | 0.0003 | 1.01 | 0.002 |

| Year 4 | 0.45 | <.0001 | −0.01 | 0.92 | 2.30 | <.0001 | 0.86 | 0.01 |

| Group*Time | ||||||||

| Int*Year 1 | 1.68 | <.0001 | 4.95 | <.0001 | −5.14 | <.0001 | −0.84 | 0.001 |

| Int*Year 2 | 1.50 | <.0001 | 4.15 | <.0001 | −3.86 | <.0001 | −0.05 | 0.90 |

| Int*Year 3 | 1.59 | <.0001 | 4.03 | <.0001 | −4.26 | <.0001 | −0.00 | 0.99 |

| Int*Year 4 | 1.40 | <.0001 | 3.77 | <.0001 | −3.30 | <.0001 | −.32 | 0.46 |

| Intercept | 2.97 | <.0001 | 11.81 | <.0001 | 30.09 | <.0001 | 82.95 | <.0001 |

N=1510, Participants with baseline body mass index <25 kg/m2 or without weight data at all follow-up visits have been excluded in the analyses.

Int: Intervention; β= Beta coefficient; p=p-value.

Group (ref= control); Time (ref=baseline)

Secondary analyses showed that weight change at 1-year follow-up was strongly but inversely associated with a change in total fiber (beta coefficient = −0.08, p <0.0001) and moderately but proportionately with a change in percent energy from fat (beta coefficient = 0.05, p <0.01); change in fruit and vegetable intake was not found to be associated with weight change (beta coefficient = −0.01, p <0.81) (Data not shown).

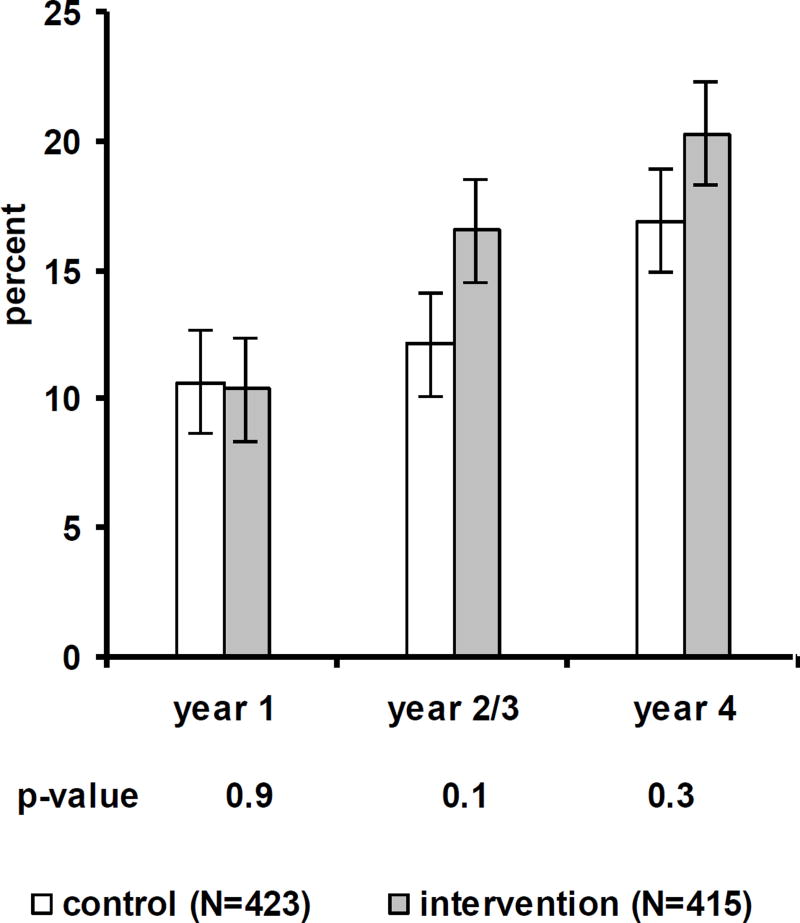

The incidence of subsequent obesity among women who were overweight at study entry was 10.6%, 14.3%, and 18.6% at year 1, 2 or 3, and 4 respectively. Obesity incidence did not vary by study group at any follow-up time (p for year 1, 2 and 3, and 4 were 0.9, 0.1, and 0.3 respectively) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Incidence of obesity in the control and in the intervention group over the study period. The Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) Study.

N=838. Only the overweight (24.99<BMI ≤ 29.99 kg/m2) at baseline were included in the analyses; error bar = standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

In this dietary intervention of women with a history of breast cancer, overweight or obese participants assigned to the intervention arm significantly changed their diets by increasing their fruit, vegetable, and fiber intake, and by decreasing their percent energy consumed from fat. Participants maintained these changes over the study follow-up period. The dietary intakes in the control group remained unchanged over the course of the study. Differences in dietary intake between the groups were shown to be independent of baseline age and BMI. Mean physical activity and body weight did not vary by the study groups, either at baseline or at follow-up time points; mean caloric intake was slightly lower in intervention participants at 3 and 4 year of follow-up. A significant difference in weight change was observed between the groups in the first year of follow-up only, but not afterwards. Secondary data analysis indicated that weight decrease in the first year was associated strongly with an increase in total fiber intake and moderately with a decrease in percent energy from fat but not with an increase in fruit and vegetable intake. Finally, significantly different dietary intakes between the overweight control and intervention participants did not translate into difference in the incidence of obesity.

The clinical trial with data most comparable to that in the present study is the Polyp Prevention Trial (PPT) (Lanza et al., 2001). Both of these trials were a multi-center randomized trial, had similar dietary goals (daily 5–8 servings of fruit and vegetables, <20% of energy from fat, and approximately 30 g/d of fiber for the PPT), had large enrollment, and followed their participants for the same length of time (4 years). The intervention participants of the present study, as in the PPT, significantly increased their fruit, vegetable, and total fiber intake and decreased their percent energy from fat compared to the control group, and maintained that difference throughout the study follow-up period. However, by the end of follow-up, weight differed between study groups in PPT, but it did not between the corresponding groups in the present analyses. Although the weight change among the control group in both trials was very similar (PPT: mean=0.31 kg, WHEL subgroup: mean=0.55 kg), the intervention participants in PPT lost a small amount of weight on average (mean= −0.65 kg) whereas their counterparts in the present study actually gained a small amount of weight over time (mean=1.3 kg).

The variations of results in body weight between these two trials may be explained by a number of factors. Unlike the WHEL Study, the PPT included men, but weight data were not presented separately for gender. Hence, it is not known whether women in the PPT experienced weight change that was any different from that in men. Hormonal differences and the onset of menopause in women may lead to different weight change patterns in adult men and women. A difference in age distribution between study cohorts might explain the difference in weight change between studies. Adult women generally gain weight until 55 years of age and typically lose weight thereafter (Williamson, 1993). PPT participants were considerably older than this WHEL Study subgroup (mean age: 61(PPT) vs. 54 years). Finally, differences in dietary intake may have played a role. The mean increase of total fiber intake and decrease of percent energy from fat were considerably higher in PPT (fiber: 7–8 g/kcal; fat: 10%) than in the WHEL subgroup (fiber: 4.6 g/kcal; fat: 3.4%).

In other diet trials (Djuric et al., 2002; Smith-Warner et al., 2000) that focused on increasing fruit and vegetable intake where weight loss was not a study objective, weight did not differ by study groups and intervention participants did not lose weight. In fact, in one trial (Djuric et al., 2002), participants in the high fruit and vegetable intake group actually gained an average of 6 pounds compared to a mean loss of 5 pounds in the low-fat intake group. If fruit and vegetable intake is increased without decreasing total energy intake, weight gain is a plausible result. Also, a fruit and vegetable rich diet is not always low in energy density: the form of fruit and vegetable, cooking method, and the additional foods consumed also influence energy density of the overall diet (Rolls et al., 2004).

The diet intervention trials that reported a change in weight associated with an increase in fruit and vegetable intake also reported a significant increase in total fiber intake and a decrease in percent energy from fat (Howard et al., 2006; Lanza et al., 2001). Hence it was not possible to partition the effect of each of these factors on the reported weight change. The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trial (Howard et al., 2006) followed 48,835 post-menopausal participants for 7.5 years and showed that an increase in total fiber intake and decrease in percent energy from fat were associated with weight loss, while fruit and vegetable intake did not influence weight loss. The WHEL Study subgroup showed a significant weight loss only in the first year of follow-up. As with the WHI, weight loss in the first year was associated strongly with an increase in total fiber intake and modestly but proportionately with a decrease in percent energy from fat, but not with an increase in fruit and vegetable intake (Data not shown). Indeed, weight change is much more commonly associated with total fiber intake than it is with fruit and vegetable intake (Howarth, Saltzman, & Roberts, 2001).

The present study offers a number of valuable insights by examining stratified diet and weight data by baseline age and BMI categories. Dietary change in intervention participants occurred in each level of age and BMI except for percent energy from fat in the obese class-II. Nevertheless, body weight did not differ between the groups in any of these instances. In both groups, older women (≥55 years) generally had a higher fruit and vegetable intake, higher total fiber intake, and lower intake of energy from fat than younger women (<55 years). Also, fruit and vegetable intake and total fiber intake were lower and percent energy from fat higher as the baseline BMI increased. Intervention participants, irrespective of age and BMI categories, changed their diet the most in the first year of follow-up. Afterwards, the dietary differences between the groups decreased as the follow-up time increased. Finally, the age-stratified weight among the control group corroborated known trends (Williamson, 1993): mean weight monotonically increased in the < 55 years age group and decreased in ≥ 55 years age group as follow-up time progressed (data not shown).

The notion that an increased fruit and vegetable consumption may reduce the incidence of obesity is based on data from both epidemiological studies (He et al., 2004; Newby et al., 2003) and clinical trials (Epstein et al., 2001; Singh et al., 1994). Despite the advantage of superiority in design, the results of the clinical trials in question may not be generalized to a broader U. S. population. One trial (Singh et al., 1994) was conducted in a population in which being a vegetarian is the norm. Participants were also required to restrict their daily energy intake (Epstein et al., 2001), were followed for short duration (6 months (Singh et al., 1994) to 1 year (Epstein et al., 2001)), and were small in number (Epstein et al., 2001) (n=27). Of the epidemiological studies (He et al., 2004; Newby et al., 2003) that examined the relationship between fruit and vegetable intake and obesity, the Nurses’ Health Study (He et al., 2004) is the largest. In that study, women in the highest quintile of fruit and vegetable intake change had a 24% lower risk of becoming obese in 12 years compared to women in the lowest quintile of change. It is possible, however, that these two groups of women were so dissimilar from one another, both in observed and unobserved attributes, that the difference in fruit and vegetable consumption (median: 9.3 vs. 2.6 servings/d) was simply a correlate of that dissimilarity. In the present study, with limited confounding due to study design, the incidence of obesity was similar in control and intervention groups. Other studies, both cohort (Togo, Osler, Sorensen, & Heitmann, 2004) and clinical trials (Rock et al., 2001), also support this finding.

This study has strengths as well as limitations. The first and foremost of the strengths is its clinical trial design, whereby randomization theoretically distributes all attributes of the study participants, both measured and unmeasured evenly between the groups. The only difference was that one group received a dietary intervention and the other did not. Hence the findings that the dietary differences between the groups were not associated with any difference in weight or obesity incidence were most probably un-confounded. Although tamoxifen usage was slightly higher in the intervention group, it is unlikely that it influenced body weight; most studies(Kumar et al., 1997) have found that tamoxifen use is not associated with weight change. Unlike many other studies that use self-reported weight and height (He et al., 2004; Newby et al., 2003), this study used measured body weight and height, assuring more accurate outcome measures. Although systematic underreporting of dietary intake is common among the obese; it should not be of concern in this WHEL Study subgroup, for the obese were distributed evenly between the groups due to randomization. Finally, although it is possible that intervention participants reported their diet differently than control participants, that is unlikely to account for the dietary difference reported between study groups because plasma levels of various carotenes, biomarkers of fruit and vegetables consumption, were also found to have increased significantly among intervention participants by one year of follow-up (Pierce et al., 2006)..

This WHEL Study subgroup differed in their dietary practices from their age and year matched cohort in the U.S. general population (GP) (USDHHS, 2000). For example, the proportion of participants that consumed three servings of fruit and vegetables (WHEL subgroup: 69% vs. GP: 49%) and <30% energy from fat (WHEL subgroup: 58% vs. GP: 33%) was higher among WHEL participants—indicators suggestive of greater health consciousness. In addition, WHEL participants were generally white, highly educated, and predominantly employed. Hence the results reported in this study may not be generalizable to the population at large. Finally, it is not known what impact missing follow-up data could have had on the study results. Participants whose data were missing were comparatively younger and heavier and were more likely to have stage IIIA cancer. This study was, however, about discerning group differences and so the concern was whether attrition rate varied between the groups, which it did not (control: 13%, intervention: 15%) (data not shown).

Implications for Practitioners

This study shows that with an appropriate intervention, people can modify their dietary habits and are capable of adhering to the newly adopted diet over time. This behavioral change of adopting a diet that is less energy dense (high in fiber and low in fat), however, does not result in a reduction of total energy intake in the ad libitum context, where people are free to choose both types and quantity of food. Hence the modification of diet alone, in the absence of concomitant reduction in total energy intake and/or increase in physical activity, is unlikely to produce weight loss. Given that, people should still be encouraged to adopt a diet high in fruits, vegetables, and fiber and low in fat, for a good body of evidence suggests that such a diet helps protects against cardiovascular diseases and diabetes(Harriss et al., 2007).

Acknowledgments

This study was initiated with the support of the Walton Family Foundation and continued with funding from NCI grant CA 69375. Some of the data were collected from General Clinical Research Centers, NIH grants M01-RR00070, M01-RR00079, and M01-RR00827. The authors thank Sheila Kealey and Christine Hayes for their editorial support.

References

- Ball K, Crawford D, Ireland P, Hodge A. Patterns and demographic predictors of 5-year weight change in a multi-ethnic cohort of men and women in Australia. Public Health Nutr. 2003;6:269–281. doi: 10.1079/PHN2002431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1625–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djuric Z, Poore KM, Depper JB, Uhley VE, Lababidi S, Covington C, et al. Methods to increase fruit and vegetable intake with and without a decrease in fat intake: compliance and effects on body weight in the nutrition and breast health study. Nutr Cancer. 2002;43:141–151. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC432_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Gordy CC, Raynor HA, Beddome M, Kilanowski CK, Paluch R. Increasing fruit and vegetable intake and decreasing fat and sugar intake in families at risk for childhood obesity. Obes Res. 2001;9:171–178. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin PJ, Ennis M, Pritchard KI, Trudeau ME, Koo J, Madarnas Y, et al. Fasting insulin and outcome in early-stage breast cancer: results of a prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:42–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harriss LR, English DR, Powles J, Giles GG, Tonkin AM, Hodge AM, et al. Dietary patterns and cardiovascular mortality in the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:221–229. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He K, Hu FB, Colditz GA, Manson JE, Willett WC, Liu S. Changes in intake of fruits and vegetables in relation to risk of obesity and weight gain among middle-aged women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:1569–1574. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard BV, Manson JE, Stefanick ML, Beresford SA, Frank G, Jones B, et al. Low-fat dietary pattern and weight change over 7 years: the Women's Health Initiative Dietary Modification Trial. Jama. 2006;295:39–49. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howarth NC, Saltzman E, Roberts SB. Dietary fiber and weight regulation. Nutr Rev. 2001;59:129–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2001.tb07001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Kozlow M, Rock CL, Gilpin EA, Hollenbach KA, Pierce JP. Validation of the WHI brief physical activity questionnaire among women diagnosed with breast cancer. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31:193–202. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kral TV, Roe LS, Rolls BJ. Does nutrition information about the energy density of meals affect food intake in normal-weight women? Appetite. 2002;39:137–145. doi: 10.1006/appe.2002.0498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar NB, Allen K, Cantor A, Cox CE, Greenberg H, Shah S, et al. Weight gain associated with adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in stage I and II breast cancer: fact or artifact? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1997;44:135–143. doi: 10.1023/a:1005721720840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza E, Schatzkin A, Daston C, Corle D, Freedman L, Ballard-Barbash R, et al. Implementation of a 4-y, high-fiber, high-fruit-and-vegetable, low-fat dietary intervention: results of dietary changes in the Polyp Prevention Trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:387–401. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCI. Action guide for healthy eating. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Newby PK, Muller D, Hallfrisch J, Qiao N, Andres R, Tucker KL. Dietary patterns and changes in body mass index and waist circumference in adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:1417–1425. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.6.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paeratakul S, White MA, Williamson DA, Ryan DH, Bray GA. Sex, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and BMI in relation to self-perception of overweight. Obes Res. 2002;10:345–350. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Faerber S, Wright FA, Rock CL, Newman V, Flatt SW, et al. A randomized trial of the effect of a plant-based dietary pattern on additional breast cancer events and survival: the Women's Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) Study. Control Clin Trials. 2002;23:728–756. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(02)00241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Natarajan L, Sun S, Al-Delaimy W, Flatt SW, Kealey S, et al. Increases in Plasma Carotenoid Concentrations in Response to a Major Dietary Change in the Women's Healthy Eating and Living Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1886–1892. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock CL, Thomson C, Caan BJ, Flatt SW, Newman V, Ritenbaugh C, et al. Reduction in fat intake is not associated with weight loss in most women after breast cancer diagnosis: evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2001;91:25–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls BJ, Ello-Martin JA, Tohill BC. What can intervention studies tell us about the relationship between fruit and vegetable consumption and weight management? Nutr Rev. 2004;62:1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh RB, Niaz MA, Ghosh S. Effect on central obesity and associated disturbances of low-energy, fruit- and vegetable-enriched prudent diet in north Indians. Postgrad Med J. 1994;70:895–900. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.70.830.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Warner SA, Elmer PJ, Tharp TM, Fosdick L, Randall B, Gross M, et al. Increasing vegetable and fruit intake: randomized intervention and monitoring in an at-risk population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:307–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinburn BA, Caterson I, Seidell JC, James WP. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of excess weight gain and obesity. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7:123–146. doi: 10.1079/phn2003585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Togo P, Osler M, Sorensen TI, Heitmann BL. A longitudinal study of food intake patterns and obesity in adult Danish men and women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:583–593. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDHHS. Home health and garden bulletin no. 232. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- USDHHS. Healthy People 2010 (Conference Edition, in Two Volumes) 2000 from http://www.healthypeople.gov/Publications/

- WHI. [Retrieved July 22, 2007];WHI Personal Habits Questionnaire. 1998 from http://www.whiscience.org/data/forms/F34v2.pdf.

- Williamson DF. Descriptive epidemiology of body weight and weight change in U.S. adults. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:646–649. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-7_part_2-199310011-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]