Abstract

Substantial preclinical and clinical research into chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) has come to fruition in the last five years, generating a clear understanding of a complex cytokine-driven cellular network. cGVHD is mediated by naive T cells differentiating within IL-17–secreting T cell and follicular Th cell paradigms to generate IL-21 and IL-17A, which drive pathogenic germinal center (GC) B cell reactions and monocyte-macrophage differentiation, respectively. cGVHD pathogenesis includes thymic damage, impaired antigen presentation, and a failure in IL-2–dependent Treg homeostasis. Pathogenic GC B cell and macrophage reactions culminate in antibody formation and TGF-β secretion, respectively, leading to fibrosis. This new understanding permits the design of rational cytokine and intracellular signaling pathway–targeted therapeutics, reviewed herein.

Introduction

Allogeneic stem cell or bone marrow transplantation (hereafter referred to as BMT) remains a cornerstone curative therapy for high-risk hematological malignancy and severe immune deficiencies (1). Chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) is a multisystem inflammatory disease characterized by tissue fibrosis and mucosal lichenoid plaques that develop late after BMT and now represents the major cause of procedural morbidity and nonrelapse mortality (2, 3). While cGVHD has been historically defined by its time of onset (more than 100 days after BMT), it is now classified on the basis of clinical diagnostic features that typically involve cutaneous and/or pulmonary fibrosis (scleroderma and bronchiolitis obliterans [BO], respectively), oral lichenoid lesions, and myofascial manifestations, although it can affect virtually any organ in the recipient (4, 5). These changes to diagnosis and severity criteria have been generated in the last decade in an attempt to address difficulties with reproducible clinical staging and response criteria (6, 7) that have previously hindered the testing of therapeutics in appropriate controlled clinical trials.

Our understanding of cGVHD has improved dramatically in the last five years and is now conceptualized as a complex immunological process incorporating multiple facets of adaptive and innate immunity, including B cells, T cells, and macrophages together with their interactions with target tissues. Cytokines can be secreted by most cell lineages and orchestrate cellular responses that include migration, activation, and growth. This Review focuses on the cytokines that coordinate the cellular and molecular determinants of cGVHD, outlining the pivotal soluble and surface-expressed mediators controlling disease at a cellular and extracellular level. Given the complexity of cGVHD, we will discuss cytokine effects in the context of relevant cellular mediators of disease and outline potential therapeutic approaches based on insights gained in preclinical models.

Since this Review cannot cover all aspects of the pathogenesis of GVHD, there are multiple additional reviews, both within this series in the JCI and elsewhere, focused on acute (8, 9) and chronic GVHD (10–12) that can provide a broad overview of the GVHD disease process. It should be noted that most of our recent understanding of cGVHD pathogenesis, particularly in relation to cytokine biology, has been developed in murine systems, and recent reviews have highlighted the pros and cons of these studies (1, 13). Where information exists, these broad pathogenic principles have been confirmed in patients undergoing BMT, and thus, this Review will focus on cytokine-dependent regulation of disease in mice and patients.

Modeling cGVHD clinical manifestations in mice

The incidence of moderate to severe cGVHD has increased over the last two decades because of the widespread use of granulocyte CSF–mobilized peripheral blood stem cells (G-PBSCs) over unmanipulated BM grafts. It is now clear that the enhanced and accelerated engraftment seen with G-PBSCs versus BM is countered by higher levels of cGVHD (14, 15). Other risk factors for cGVHD include the use of HLA-mismatched and unrelated donors, recipient age, and absence of antithymocyte globulin in conditioning (16). The increasing use of G-PBSC–mismatched donors and the routine transplantation of patients over 60 years old have led to a dramatic increase in the burden of cGVHD (14).

It is notable that cGVHD may develop in the context of preceding acute GVHD (aGVHD), whether effectively treated or developing as a continuum from acute disease (17). Indeed, prior aGVHD is a powerful and important risk factor for subsequent cGVHD (18). Furthermore, it has recently been appreciated that GVHD “breaking through” prophylaxis (usually immune suppression with calcineurin inhibitors) may have distinct immunological features from GVHD that develops in the absence of calcineurin inhibitors (19); this is an important potential consideration for therapy.

Historically, mouse cGVHD studies were often generated in the absence of conditioning therapy by infusion of parental splenocytes into semiallogeneic F1 hosts, resulting in a lupus-like reaction (reviewed in refs. 20, 21). However, these models did not well simulate the wider spectrum of clinical cGVHD, and, since no conditioning or donor hematopoietic cells were infused, host immune elements were major contributors to disease pathogenesis. The dominant disease manifestations were glomerulonephritis with scleroderma that was associated with single-stranded DNA autoantibodies. Today, mouse models of BMT typically use total-body irradiation–based conditioning and BM grafts together with purified splenic and/or lymph node–derived T cells to induce GVHD (22). More recently, granulocyte CSF–mobilized (G-CSF–mobilized) splenocytes have been used to model G-PBSCs, which generally results in more severe cGVHD compared with models using unstimulated splenocytes (23).

While models are characteristically defined as giving rise to aGVHD or cGVHD, in practice, it is not always possible to clearly distinguish the two pathologies. Indeed, donor T cell dose, donor/recipient strain combinations, and environmental conditions dictate the extent to which the recipient experiences aGVHD and/or cGVHD. Thus, early mortality (in the first 2 weeks) after BMT with high T cell doses is typically a result of CD4-dependent aGVHD of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (1), whereas disease features typical of cGVHD occur 4–8 weeks after BMT with low T cell doses that avoid early mortality and cause chronic T cell stimulation and subsequent antibody production (23–28). We believe that clinically relevant cGVHD is not unique to models of GVHD in response to minor histocompatibility antigens but rather reflects the nature of the immune response in the model, e.g., CD4 versus CD8 T cells and their respective differentiation and cytokine/chemokine expression patterns. Nevertheless, as in clinical practice, features of aGVHD in the GI tract and liver and cGVHD in skin and lung often coexist, reflected by the current NIH criteria (5). Clinical cGVHD can affect almost any target tissue, making modeling in preclinical systems challenging. Nevertheless, the predominant and diagnostic organ pathologies that develop are usually scleroderma or BO, although, for potentially important reasons that are yet to be defined, disease seldom coexists in these two organs within animal systems. Additional features of cGVHD have been described in the tongue, salivary and lacrimal glands, and eye; such pathology requires histological confirmation and grading in severity (29–31). Pulmonary function tests are also particularly informative for determining the severity of BO; however, these tests are technically challenging and available in a limited number of laboratories (27, 28). To date, reliable models and functional determinants of manifestations of cGVHD such as Sjögren’s syndrome are generally lacking and represent an important unmet need in the field.

aGVHD: setting the stage for cGVHD

As noted, aGVHD is often a portent of cGVHD, suggesting that the pathophysiology of the two processes is linked. Recent lessons from the translation of preclinical approaches to prevent GVHD, predominantly post-transplant cyclophosphamide (32), which depletes alloreactive T cells while sparing Tregs, and selective ex vivo naive T cell depletion (33), have resulted in dramatic reductions in cGVHD, but not aGVHD (34, 35). These data indicate that the expansion and differentiation of naive T cells in the donor graft are central to cGVHD pathogenesis. The initial stages of T cell differentiation occur in an inflammatory and lymphopenic environment, a result of the chemoradiotherapy used in conditioning (36). Thus, elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines, particularly IL-6 and to a lesser extent IL-1 and TNF (37), act in concert with products of luminal damage-associated and pathogen-associated molecular patterns to modify and augment both alloantigen presentation and T cell differentiation (38, 39). While this inflammatory storm favors differentiation of IFN-γ–secreting CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Th1 and Tc1, respectively) and IL-17–secreting CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Th17 and Tc17, respectively) (Figure 1), and resultant target organ apoptosis (36, 40–43), in the clinic this process is highly modified by pharmacological immune suppression (37). Thus, the process is modulated and can be delayed relative to that seen in preclinical systems where pharmacological immune-suppressive agents are seldom given after BMT (44). Indeed, the intense early post-BMT TNF/IL-1/IFN-γ dysregulation seen in animal systems is not fully recapitulated in the clinic; therefore it is possible that murine systems may overestimate the Th1/Tc1 dominance of aGVHD.

Figure 1. Cytokines and signaling pathways associated with the effector populations of cGVHD.

(A) T effector cells respond to MHC/peptide on antigen presenting cells (APC) and, in the context of IL-6–, IL-23–, and IL-21–stimulated STAT3 phosphorylation, transcribe RORC to drive Th17 and Tc17 differentiation with secretion of IL-17 and related cytokines. IL-12 stimulation promotes T cell–specific T-box transcription factor (TBET) transcription and IFN secretion that signals in an autocrine fashion to enhance Th1 differentiation. Tbet expression and IFN-γ secretion are also characteristic of Th17/Tc17 cells after BMT. (B) Tregs respond to antigen within MHC class II and concurrent TGF-β and IL-2 signaling, which promotes STAT5 phosphorylation, SMAD signaling, and subsequent FOXP3 transcription. Immune regulation by secreted IL-10 and TGF-β ensues. (C) Tfh, identified by ICOS, CXCR5, and PD-1 expression, respond to antigen presented within MHC class II in the context of IL-6, IL-27, and IL-21 stimulation to drive STAT3 phosphorylation and BCL6 transcription, with subsequent secretion of IL-21. (D) BAFF and IL-21 drive GC B cell expansion and, in the context of B cell receptor signaling, subsequent SYK and BTK transcription promotes survival and allo- and autoantibody secretion. BLNK, B cell linker; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T-cells; BCR, B cell receptor; PLC, phospholipase C.

Although aGVHD and cGVHD impair donor B cell differentiation in the BM and aGVHD causes peripheral B cell depletion (1, 45–47), it is also now clear that aberrant B cell expansion is a feature of cGVHD (28, 29). In addition to B cell depletion, the thymus is a primary target of aGVHD (48), setting the scene for aberrant T cell selection and differentiation later after BMT (30). In cGVHD it is therefore possible that donor T cells may be both auto- and alloreactive (25); indeed, T cells from animals with cGVHD can induce disease in syngeneic recipients (30).

Adaptive immunity: cytokine-dependent T and B cell differentiation

IL-6 and Th17/Tc17.

T cell differentiation after BMT is characterized by a number of pathogenic and protective paradigms. Unlike other proinflammatory cytokines, IL-6 dysregulation after BMT occurs in response to conditioning and is largely independent of immune suppression (37, 44). IL-6 is a pleiotropic cytokine that can be produced by most cells; production by monocytes and macrophages dominates (49). The cytokine signals through a trimer receptor complex that involves IL-6R and gp130 (50). IL-6R expression is relatively limited in distribution to some T cells, monocyte-macrophages, and hepatocytes, while gp130 is ubiquitously expressed (49). Classical IL-6 signaling through this receptor complex results in phosphorylation of STAT3, which is critical for the generation of cGVHD (51, 52). In T cells, this pathway drives expression of the transcription factor (TF) RAR-related orphan receptor-γt (RORγt) and the generation of cytokine gene products characteristic of Th17/Tc17 differentiation (41, 53). This differentiation pattern appears to be augmented by stem cell mobilization with G-CSF, which provides a link between cGVHD predilection and G-PBSC grafts (23). Recently, the use of cell fate–reporter systems has made it clear that Th17/Tc17 differentiation after BMT is highly promiscuous and plastic in nature (41). In particular, IL-17 secretion is transient, and, despite continuously elevated RORγT expression, the dominant cytokine signature over time is IFN-γ and TNF (Th1 cytokines). Importantly, the Tc17 lineage appears to have limited capacity for cytolysis with low levels of granzyme B production and minimal capacity to mediate graft-versus-leukemia effects (41, 54). Tc17 also express high levels of T-bet and, over time, after both preclinical and clinical BMT (37), exhibit concurrent dysregulation of both IFN-γ and IL-17, consistent with a role for this lineage in cGVHD. Indeed both scleroderma and BO fail to develop in animals in the absence of IL-17A and/or RORC (23, 24), consistent with a central role for this pathway in disease.

In the clinic, the nature of cells infiltrating target organs remains poorly defined, likely reflecting differences over time and within individual organs. Nevertheless, Th1/Tc1, Th17/Tc17, and RORγT are all seen at cGVHD sites (55–57), as well as STAT3 phosphorylation, which has been suggested to predict GVHD (37, 57, 58). Recently, nonhuman primate systems demonstrated the dominance of the Th17/Tc17 differentiation pattern in animals developing GVHD that breaks through immune suppression (19), akin to the breakthrough observed in patients. A number of studies have demonstrated the importance of IFN-γ in sclerodermatous cGVHD, with or without IL-17A (59–62). In contrast, a protective role for Th1 cytokines has been described in lung disease, including BO (42, 44, 63). Other Th17/Tc17 cytokines include granulocyte-macrophage CSF (GM-CSF) and CSF-1, both of which play critical roles in monocyte-macrophage biology (64, 65) (their role in cGVHD is described below), and IL-22, a cytokine known to be important in the protection of the GI tract from GVHD when secreted by recipient innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) (66, 67). Whether IL-22 within the GI tract is from ILCs or from Th17 or a divergent Th22 lineage has yet to be determined. IL-22 also has proinflammatory properties (68, 69), and a pathogenic role of donor T cell–secreted IL-22 has been described in GVHD. This function is related, at least in part, to the suppression of Tregs and host type I IFN/STAT1 signaling (70, 71). Ongoing clinical trials of exogenous IL-22 IgG2-Fc fusion protein to treat patients with lower-GI aGVHD (NCT02406651, ClinicalTrials.gov) will determine the extent to which the intestinal reparative effects might outweigh potential pathogenic proinflammatory effects of IL-22.

The inhibition of IL-6 has shown impressive protection from aGVHD in preclinical models in association with inhibition of Th17 differentiation, Treg expansion (72), and direct inhibition of target cell apoptosis (73). Promising clinical data have also suggested an effect in patients, with low incidence of aGVHD seen in those receiving IL-6R inhibition for 3–4 weeks after BMT. In this setting, protection was associated with modification of myeloid and T cell responses (37). Importantly, short-term IL-6 inhibition did not seem to influence the development of cGVHD, suggesting that long-term IL-6 inhibition would be required to prevent cGVHD. Alternatively, these findings indicate that IL-17 differentiation late after BMT is independent of IL-6 (see below).

IL-21 and Tfh.

The differentiation of Tfh is defined by the BCL6 TF and surface expression of CXCR5 and programmed death-1 (PD1) (74). Tfh cells express high levels of IL-21, which drives germinal center (GC) B cell formation and antibody secretion (28, 74). While autoantibodies are widely seen in patients with cGVHD, their role (i.e., cause versus effect) in disease remains unclear. In contrast, alloantibody generation in conjunction with GC B cell expansion has been observed in cGVHD models (28, 29, 75). Inhibition of IL-21/IL-21R signaling prevented GC expansion and alloantibody formation, as well as disease (23, 28). Furthermore, serum transfer experiments confirmed the ability of alloantibody to induce cGVHD (76), and H-Y alloantibodies correlated with disease in clinical sex-mismatched donor/recipient pairs (77, 78). Whether alloantibody is present in all patients and involved in disease universally is currently unclear. Likewise, whether the major pathogenic sources of IL-21 are Tfh, Th17, or a recently described IL-6–dependent CD8+ T cell lineage also is unclear (79).

B cells.

B cell generation is disrupted during GVHD, leading to elevations in immature and transitional B cells and defects in memory populations, which exhibit enhanced sensitivity to B cell activating factor (BAFF) (80, 81). BAFF is produced primarily by myeloid cells, stromal cells, and some lymphoid cells and is a transmembrane protein that can be cleaved into a soluble form. The BAFF receptor (BAFFR) is expressed by B cells and plasma cells and determines immature B cell survival and maturation (82). BAFF/B cell ratios are elevated in patients with active cGVHD (83–85), and this elevation is associated with alterations in GC B cells and the presence of plasma cell–like populations, consistent with a state of B cell hyperactivation (84). Given that inhibitors of this pathway are in clinical use, it is important to study this pathway in depth in relevant preclinical models. Moreover, since plasmablasts and plasma cells produce copious amounts of antibodies, strategies described below to target these cell populations may be useful in overcoming BAFF-mediated signaling events.

IL-2 and Tregs.

The differentiation of T cell lineages with regulatory capacity has been widely described and has focused principally on FoxP3+ Tregs (86), but also more recently on FoxP3–IL-10+ Treg type 1 (Tr1) cells (87). Tregs may be generated centrally in the thymus (tTregs) or induced peripherally (iTregs) under the influence of TGF-β and antigen presentation within MHC class II. FoxP3 expression appears to be much more stable in tTregs, but both Treg subtypes are characterized by expression of the high-affinity IL-2 receptor CD25 (88). Thymic Treg production (26, 30) and peripheral Treg homeostasis are perturbed, and Treg numbers are reduced in cGVHD (89, 90). In preclinical BMT models, Treg depletion induces cGVHD, and adoptive Treg transfer can ameliorate disease (25, 91). Donor DCs are essential for maintaining donor Treg homeostasis after BMT (25, 92). Importantly, aGVHD profoundly impairs antigen presentation within MHC class II (93), providing a causal link between aGVHD and the development of Treg deficiency and subsequent cGVHD (25).

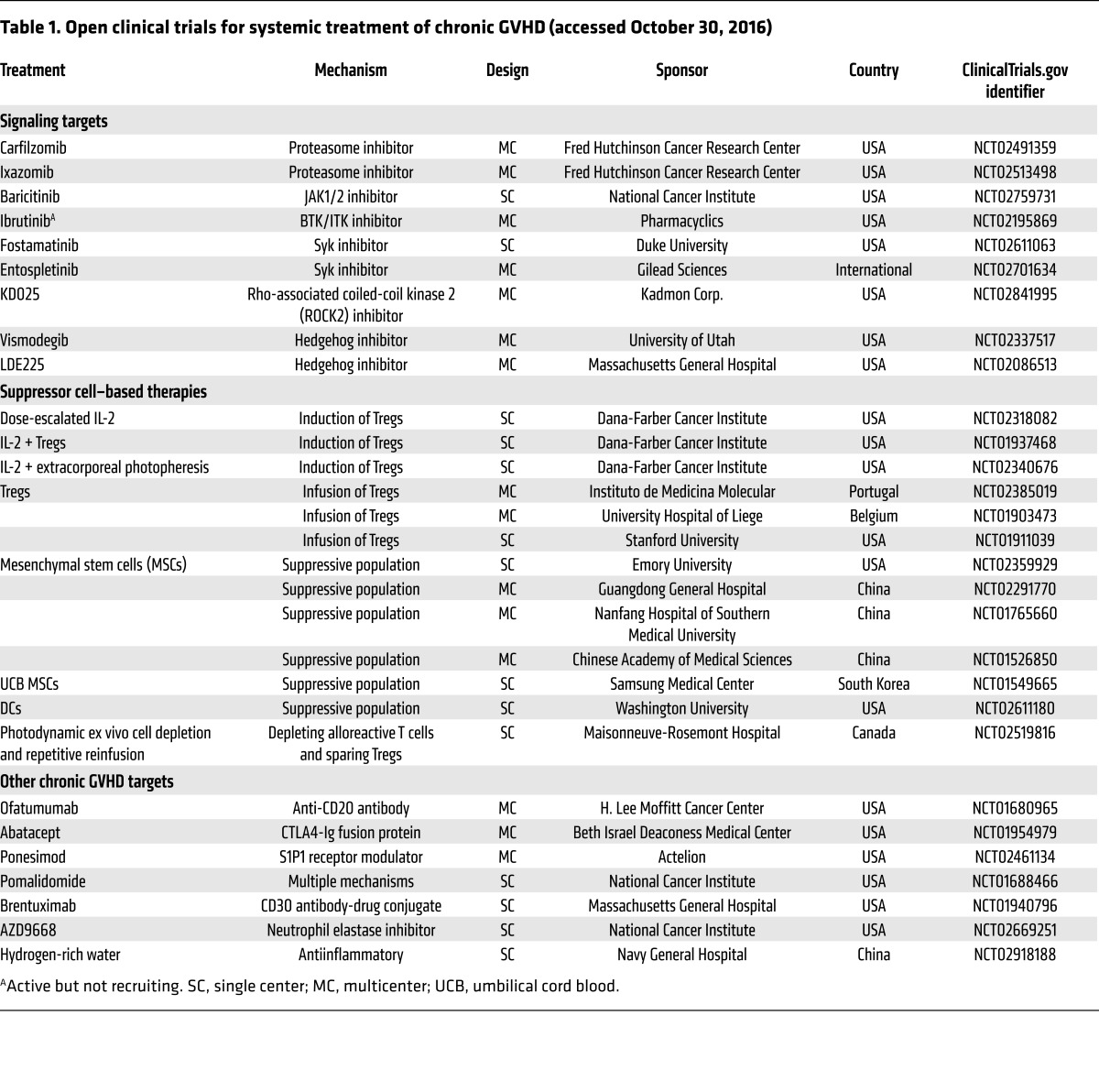

A number of elegant studies have demonstrated that exogenous IL-2 administration can enhance Treg numbers and induce responses in about half of patients with steroid-refractory cGVHD (94–97). It appears that ongoing treatment is necessary to maintain responses (96), yet it is currently unclear whether adoptive Treg transfer, with or without IL-2, can further improve response rates, which will be clarified by several ongoing worldwide clinical trials (Table 1). The ability of alternative cytokines (either long-acting IL-2 mutants or other common γ chain cytokines) to enhance regulatory responses remains a burgeoning area of interest.

Table 1. Open clinical trials for systemic treatment of chronic GVHD (accessed October 30, 2016).

IL-10.

The role of the Tr1 lineage in cGVHD is presently unclear, but these cells are known to regulate immune responses via IL-10, which is an important mechanism by which Tregs and B cells modulate GVHD (98–100). Whether the regulatory effects of IL-10 are principally from myeloid cells (101), Tr1 or Treg populations (102, 103), or so-called regulatory B cells (104, 105) is unclear and deserves further study. IL-10 signals through IL-10R, which is principally expressed on immune cells, and can promote Treg differentiation and licensing, regulate TNF secretion, and inhibit effector T cell proliferation, most likely owing to inhibitory effects on antigen-presenting cells (reviewed in ref. 106). IL-10 is also induced by nonhematopoietic cells following G-CSF–mediated stem cell mobilization (107, 108) and enhances Treg expansion early after BMT (109). Thus, IL-17 induction and IL-10 induction appear to be divergent mechanistic pathways by which the transplantation of G-PBSCs results in a profound augmentation of cGVHD but has relatively little effect on the incidence of aGVHD. Because IL-10R is also expressed on Th17 (110) and CD8+ T cells (111), and high-dose exogenous IL-10 (112), in striking contrast to low doses (113), can drive rather than protect mice against aGVHD lethality, it is possible that during aGVHD the immunoregulatory properties of IL-10 in some patients may be offset by effects on Th17 and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. Although progress has been made on Tr1 characteristic cell surface antigens (114), investigation of Tr1 in this process is currently limited by a lack of pivotal TFs required for lineage development and/or stable surface phenotypes. These are needed to analyze the role of these cells in the BMT setting in order to optimize the potential therapeutic benefits of IL-10 (115, 116).

Cytokine-driven effector pathways in cGVHD

CSF-1 and macrophages.

CSF-1 is the master regulator of the cells of the mononuclear phagocytic system. CSF-1 signaling controls the differentiation (117), proliferation (118), migration and survival (119) of tissue-resident macrophages and their precursors (120), and contributes to DC homeostasis (121). The CSF-1 receptor (CSF-1R), a class III RTK belonging to the PDGF family, is expressed at high levels on monocytes and macrophages. CSF-1R is also broadly expressed at low levels on multiple lineages, including hematopoietic (122) and neural stem cells (123), DCs, microglia (124), osteoclasts (125), and Paneth cells (126). As such, CSF-1 signaling contributes to embryonic development, homeostasis, innate and acquired immunity, and tissue repair. Consistent with these roles, impaired CSF-1 signaling is implicated in multiple disease states.

In macrophages, CSF-1R ligation leads to the autophosphorylation of the intracellular tyrosine residues and subsequent phosphorylation of several kinase signaling systems, including PI3K (127), MEK, and the Tek family kinases Tec and Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) (128). Other components of the CSF-1 signaling pathways include SHIP1, ERK1/2, AKT, p38, JNK, and ERK5, which together regulate diverse downstream functional decisions, including proliferation, differentiation, and survival (reviewed in ref. 129 and shown in Figure 2).

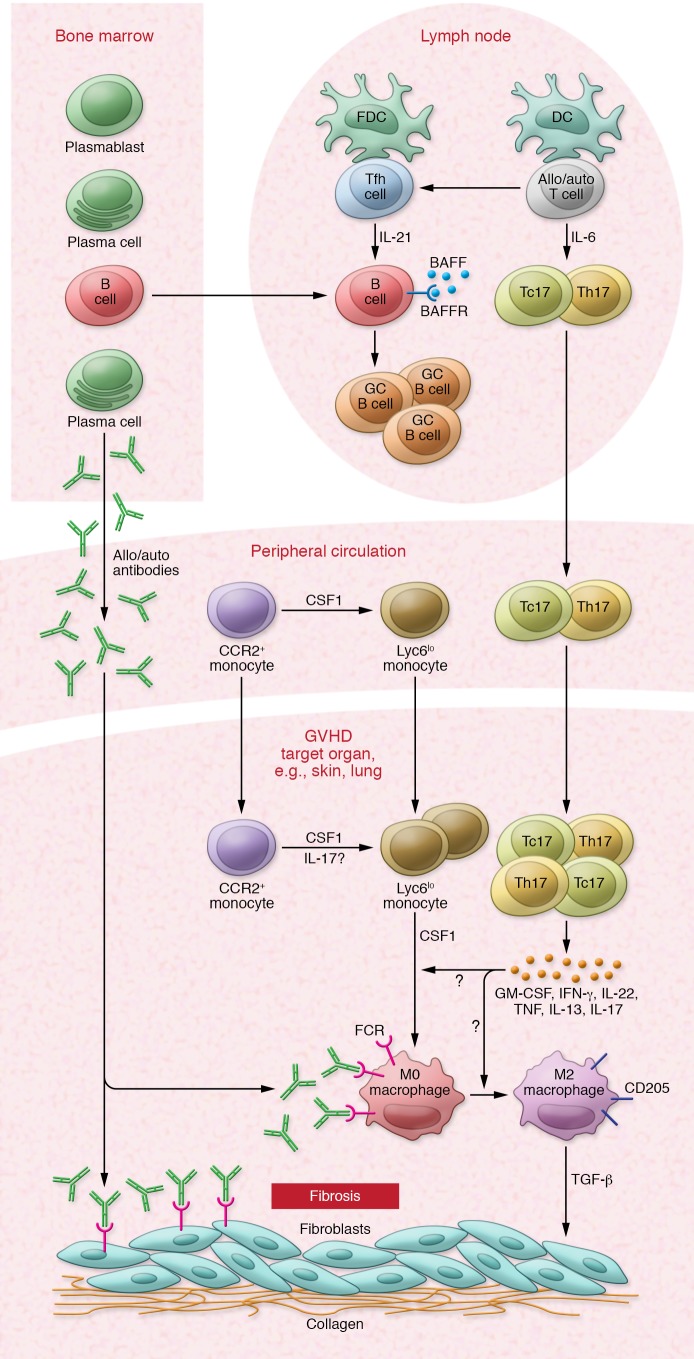

Figure 2. Overview of the cytokine-driven cellular network driving cGVHD.

cGVHD is now recognized as a Th17/Tc17- and Tfh-mediated disease. DC priming of naive allogeneic T cells in the setting of elevated IL-6 production after BMT drives RORγt expression and Th17/Tc17 differentiation and accumulation in target tissues. Increased Tfh, GC B cells, and antibody, which accumulate in target tissues, contribute to cGVHD pathology. Tfh express high levels of IL-21, which, together with elevated levels of BAFF, drive GC B cell formation and antibody secretion. CSF-1–dependent macrophages are late-phase mediators of cGVHD pathology. Th17/Tc17 are polyfunctional and coexpress high levels of multiple cytokines, including IFN-γ, TNF, IL-22, CSF-1, and GM-CSF, which are implicated in promoting the migration and differentiation of Ly6Clo monocytes into pathogenic M2 macrophages. Plasma cell–derived allo- and autoantibodies can bind to Fc receptors on macrophages, potentially contributing to their polarization. Through their secretion of TGF-β, Ly6Clo-derived macrophages promote fibroblast activation and collagen production, leading to tissue fibrosis. Adapted with permission from Blood (11).

Although some studies have shown that the pretransplant conditioning regimen leads to the release of inflammatory cytokines by host macrophages (36), others have demonstrated that host macrophages that persist after BMT can reduce GVHD by engulfing donor T cells (120, 130, 131) and pre-BMT CSF-1 can expand macrophages, thereby suppressing aGVHD lethality (131). In cGVHD, accumulating evidence demonstrates a critical role for CSF-1–dependent monocytes and macrophages in fibrogenesis. In most fibrotic tissues, including clinical cGVHD lesions, macrophages are abundant and are found in close proximity to collagen-producing myofibroblasts (55, 132). In multiple preclinical models of cGVHD, macrophage sequestration into GVHD target organs has been shown to be both IL-17– and CSF-1–dependent (23, 24). Critically, the disruption of CSF-1 signaling following BMT using an anti–CSF-1R mAb (M279) depleted tissue macrophages and attenuated cGVHD-associated cutaneous and pulmonary fibrosis. Importantly, CSF-1R blockade also specifically ablated Ly6Clo monocytes, the established tissue-resident macrophage precursors (120). The infiltrating macrophages, which were of donor origin, exhibited an antiinflammatory M2-skewed phenotype, and were capable of promoting fibrosis via their secretion of TGF-β and possibly other profibrogenic proteins (24).

IL-17 may contribute directly to myeloid cell sequestration and differentiation, as both monocytes and macrophages express high levels of the IL-17A receptor (133) and IL-17 signaling in these cells elicits multiple functions including chemotaxis and activation (134, 135). However, Tc17, which are implicated in mediating macrophage sequestration, also express other proinflammatory cytokines, including GM-CSF (41), which may contribute synergistically to macrophage differentiation/polarization at localized sites. The factors driving aberrant macrophage differentiation and the potential role of alloantibody in this process are unclear but require investigation. Notably, Tec and BTK are essential regulators of macrophage CSF-1 signaling (128), contributing to both survival and GM-CSFRα expression, thus representing a therapeutically targetable downstream pathway.

TGF-β.

The TGF-β family of growth factors controls proliferation, differentiation, and survival in many cell types. TGF-β is secreted by cells of multiple lineages, including cells of mesenchymal (136) and hematopoietic (137) origin. The relative contribution of TGF-β isoforms appears to be contextual, with TGF-β1 as the predominant isoform in the immune system (138). TGF-β is secreted in latent form and is unable to engage its receptors (139). The proteolytic degradation of the latent peptides renders TGF-β biologically active. Once activated, signaling is elicited through an oligomeric complex composed of type I and type II serine/threonine kinase receptors. TGF-β first binds to the constitutively phosphorylated TGF-RII, which in turn binds to and phosphorylates TGF-RI, leading to the activation of the cytoplasmic signaling molecules Smad2 and Smad3 (140, 141), which translocate to the nucleus to regulate target gene expression. Additionally, other noncanonical TGF-β–activated pathways, including MAP kinase, Rho-like GTPase, and PI3K/AKT pathways, collectively contribute to signaling outcomes (142). TGF-β signaling mediates diverse biological responses and plays a role in tissue regeneration (143) and the maintenance of immune tolerance (138). Aberrant TGF-β expression and signaling are implicated in the profound immune dysregulation that occurs after BMT and in cGVHD-associated fibrotic manifestations (144–147).

Following injury, TGF-β signaling promotes both the production and degradation of various extracellular matrix proteins and is therefore instrumental in tissue repair (143). In all tissues, fibroblasts are the primary producers of extracellular matrix. During injury, TGF-β signaling promotes fibroblast migration, proliferation, and differentiation into α-smooth muscle actin–expressing (α-SMA–expressing) myofibroblasts, which produce large amounts of collagen. Notably, profibrogenic PDGF synergizes with TGF-β, resulting in augmented expression of both α-SMA and collagen by myofibroblasts (148). In preclinical models and patients, cGVHD is associated with elevated TGF-β levels in the serum and target organs, and TGF-β is negatively correlated with survival (144, 147, 149, 150). Furthermore, cGVHD patients harbor elevated levels of agonistic PDGFR antibodies, although whether these are involved in disease pathogenesis remains contentious (151, 152). Myeloid lineages that accumulate within cGVHD target organs are the primary TGF-β–producing populations (24, 146). Importantly, TGF-β neutralization effectively prevents both skin and lung fibrosis in murine models (2, 146). Although TGF-β blockade has yet to be investigated clinically, dual blockade of TGF-β and PDGFR pathways using tyrosine kinase inhibitors has shown promising results in patients with steroid-refractory cGVHD (153, 154).

TGF-β is also a key immunoregulatory cytokine that contributes to the maintenance of peripheral tolerance, as evidenced by the multiorgan inflammation and autoimmunity that occur in TGF-β cytokine– or receptor–deficient mice (138, 155). TGF-β mediates immunosuppression through inhibition of lymphocyte proliferation, differentiation, and effector function. T cell–intrinsic TGF-β signaling dampens T cell expansion via multiple mechanisms, including the suppression of IL-2 production and promotion of apoptosis (156, 157). TGF-β also potently inhibits Th1 and Th2 differentiation via downregulation of the TFs T-bet and GATA3 (158, 159). In concert with IL-2, TGF-β promotes the conversion of naive CD4+ T cells into FoxP3-expressing iTregs. Consistent with the importance of this cytokine in the generation of and regulation by Tregs (160), TGF-β inhibition early after BMT promotes aGVHD (146). Thus, following BMT, TGF-β signaling elicits both protective antiinflammatory, immunosuppressive, and pathogenic profibrogenic responses in a temporal manner, indicating that carefully timed therapeutic targeting of this pathway will be required. Alternately, targeting the cellular source of TGF-β in inflamed tissues or specific downstream signaling pathways may provide a means of selective inhibition of some but not all of the cytokine responses; the use of canonical and noncanonical signaling pathways supports the feasibility of the latter approach. For example, although TGF-β signaling is critical for tTreg generation, Smad2 and Smad3 are not required (161), suggesting that targeting these signaling components could preferentially diminish fibrogenic responses while sparing Tregs.

Pharmacological therapeutics that target cytokine signaling pathways

Steroids continue to be the mainstay of first-line cGVHD therapy; however, steroids are associated with substantial morbidity and mortality, especially when given long-term as is typically required for cGVHD patients. Guided by both rodent studies and clinical biomarker analyses, new cGVHD-targeting pathways have been elucidated, leading to new pharmacological and cellular approaches to treat this disease. A particularly successful approach has been to reuse drugs known to have validated immunological and antiinflammatory properties as well as an acceptable safety profile in inflammatory disease. Similarly, cellular therapies useful in aGVHD are currently being tested in cGVHD. A tabular summary of active trials in cGVHD is provided in Table 1. Those and related completed trials involving pharmacological agents directly regulating cytokine production or responses will be discussed below.

Bortezomib (Velcade) is the first therapeutic proteosomal inhibitor to be tested in humans for treatment of multiple myeloma. Studies in murine aGVHD indicated that bortezomib and a related compound promoted alloantigen-specific T cell deletion and inhibited proinflammatory responses associated with NF-κB upregulation (162, 163). In a sclerodermatous minor histocompatibility antigen–mismatched model of cGVHD, bortezomib reduced serum and skin IL-6 levels and proved efficacious in treating skin manifestations of cGVHD in patients in preliminary studies (164). A phase II study of bortezomib combined with prednisone resulted in organ-specific complete response rates of 73% for skin, 53% for liver, 75% for the GI tract, and 33% for diseased joint, muscle, or fascia, and permitted a 60% median prednisone dose reduction by week 15 (165). Carfilzomib, a peptidylepoxyketone, and ixazomib, a peptide analog, both inhibit the 20S proteosomal subunit β type 5 and are being tested for efficacy in cGVHD therapy (Table 1). Ruxolitinib, which is approved for the treatment of myelofibrosis, and baricitinib are selective JAK1/2 inhibitors. JAK1/2 signaling regulates T cell activation and survival through the IL-2 common chain, a constituent of the receptor complexes for IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15, and IL-21; targeting JAK1/2 signaling ameliorated murine aGVHD and cGVHD (166). In a preclinical antibody-mediated, multiorgan system model of cGVHD that includes BO, ruxolitinib therapy reversed active cGVHD manifestations (167). In 41 patients with steroid-resistant cGVHD, the overall response rate to ruxolitinib was 85% (167).

Ibrutinib targets B cell malignancies by inhibiting BTK and IL-2–inducible tyrosine kinase (ITK). Ibrutinib has been approved to treat various types of lymphoid malignancies and is known to inhibit malignant B cell responses to soluble factors in the tumor environment, including BAFF, IL-6, IL-4, and TNF-α. In a preclinical sclerodermatous cGVHD model, ibrutinib delayed progression, improved survival, and ameliorated cGVHD manifestations. In the antibody-driven cGVHD model, ibrutinib treatment restored pulmonary function and reduced GC reactions and tissue immunoglobulin deposition; using knockout donor cells, it was established that both BTK and ITK were critical for cGVHD development (27). Moreover, ibrutinib treatment reduced activation of T and B cells from patients with active cGVHD. Based on positive phase Ib/II data, ibrutinib is entering phase III trials for treatment of steroid-dependent or refractory cGVHD (Table 1).

Spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) is an enzyme that regulates T and B cell signaling pathways and has been implicated in hematological malignancies, including those with ITK translocations. Fostamatinib is a prodrug inhibitor and entospletinib is an ATP-competitive inhibitor of Syk. In the BO model, Syk was necessary in donor B cells but not donor T cells for disease progression, and fostamatinib treatment reversed disease in both nonsclerodermatous and several sclerodermatous models (168). Syk upregulation was observed in B cells from cGVHD mice and patients, and Syk inhibition in vitro effectively induced apoptosis of human cGVHD B cells. Syk inhibitors are currently in both phase I and phase II double-blind randomized trials for treatment of cGVHD (Table 1).

Rho-associated coiled-coil kinase 2 (ROCK2) has been implicated in IL-21 and IL-17 regulation. Treatment with the selective ROCK2 inhibitor KD025 ameliorated cGVHD in multiple models. In an antibody-mediated cGVHD model, spleens of KD025-treated mice had decreased frequency of Tfh cells and increased frequency of T follicular regulatory cells along with both increased phospho-STAT3 and decreased phospho-STAT5 (52). In cGVHD patients with active disease, KD025 inhibited IL-21, IL-17, and IFN-γ secretion and phospho-STAT3. KD025 has entered phase IIa clinical trials for cGVHD therapy (Table 1).

Sonic hedgehog and its receptor patched are expressed on resting and activated human peripheral CD4+ T cells (169). In the absence of hedgehog proteins, patched-1 inhibits the coreceptor smoothened (Smo). Smo induces the TFs Gli-1 and Gli-2, which activate the SOCS1 promoter. Thus, Smo antagonists mimic hedgehog ligand absence and lead to reduced SOCS1 promoter activity and increases in IFN-γ and phospho-STAT1. Hedgehog signaling is activated in human and murine cGVHD (170). Treatment with LDE223, a highly selective small-molecule Smo antagonist, almost completely prevented sclerodermatous cGVHD development and was useful in cGVHD therapy (170). Vismodegib and LDE225 are Smo antagonists being tested in steroid-refractory chronic GVHD patients in ongoing studies. The direct targeting of a number of cytokines is now possible, and inhibition of IL-21, IL-17A, CSF-1R, or TGF-β appears to be a logical therapeutic strategy to move forward into well-designed phase I/II clinical trials.

Summary

Our understanding of the pathophysiology of cGVHD has dramatically improved over the last five years, as has our ability to undertake informative clinical trials in this setting. We are now in an exciting period in which a number of new and established therapeutics that focus on the elimination of the aberrant cytokine responses that drive fibrosis can be rapidly tested within the constraints of well-designed clinical trials to both prevent and treat cGVHD.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of our laboratories, our collaborators, and the scientific community for providing the foundation for this Review. We apologize to those investigators whose work we were unable to cite because of space restrictions. Importantly, we thank the patients who have participated in clinical studies that have fostered the advancement of the new therapies for this devastating disease. This work was supported by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NH&MRC) grant APP1031728 (to KPAM); and by National Cancer Institute grants P01-CA142106-06A1 and P01-CA047741-20, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grants P01-AI056299 and R01-AI11879, and Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Translational Research grants 6458-15 and 6462-15 (to BRB). GRH is an NH&MRC Senior Principal Research Fellow and Queensland Health Senior Clinical Research Fellow.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: G.R. Hill has received funding from Roche for clinical trials of IL-6 inhibition. B.R. Blazar declares a conflict of interest in patents submitted for methods of treating and preventing alloantibody-driven chronic graft-versus-host diseases with ibrutinib (US Provisional Application No. 14/558,297) and with the ROCK2 inhibitor KD025 (US Provisional Application No. 61/977,564).

Reference information:J Clin Invest. 2017;127(7):2452–2463.https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI90593.

References

- 1.Markey KA, MacDonald KP, Hill GR. The biology of graft-versus-host disease: experimental systems instructing clinical practice. Blood. 2014;124(3):354–362. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-514745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flowers ME, Martin PJ. How we treat chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2015;125(4):606–615. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-08-551994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin PJ, et al. Life expectancy in patients surviving more than 5 years after hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(6):1011–1016. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.6693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Filipovich AH, et al. National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and staging working group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11(12):945–956. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jagasia MH, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: I. The 2014 Diagnosis and Staging Working Group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(3):389–401.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shulman HM, et al. NIH Consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: II. The 2014 Pathology Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(4):589–603. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee SJ, et al. Measuring therapeutic response in chronic graft-versus-host disease. National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: IV. The 2014 Response Criteria Working Group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(6):984–999. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blazar BR, Murphy WJ, Abedi M. Advances in graft-versus-host disease biology and therapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(6):443–458. doi: 10.1038/nri3212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeiser R, Socié G, Blazar BR. Pathogenesis of acute graft-versus-host disease: from intestinal microbiota alterations to donor T cell activation. Br J Haematol. 2016;175(2):191–207. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Socié G, Ritz J. Current issues in chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2014;124(3):374–384. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-514752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacDonald KP, Hill GR, Blazar BR. Chronic graft-versus-host disease: biological insights from preclinical and clinical studies. Blood. 2017;129(1):13–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-06-686618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooke KR, et al. The Biology of Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: A Task Force Report from the National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23(2):211–234. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeiser R, Blazar BR. Preclinical models of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease: how predictive are they for a successful clinical translation? Blood. 2016;127(25):3117–3126. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-02-699082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stem Cell Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Allogeneic peripheral blood stem-cell compared with bone marrow transplantation in the management of hematologic malignancies: an individual patient data meta-analysis of nine randomized trials. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(22):5074–5087. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anasetti C, et al. Peripheral-blood stem cells versus bone marrow from unrelated donors. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(16):1487–1496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flowers ME, et al. Comparative analysis of risk factors for acute graft-versus-host disease and for chronic graft-versus-host disease according to National Institutes of Health consensus criteria. Blood. 2011;117(11):3214–3219. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-302109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sohn SK, et al. Risk-factor analysis for predicting progressive- or quiescent-type chronic graft-versus-host disease in a patient cohort with a history of acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;37(7):699–708. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lazaryan A, et al. Risk factors for acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation with umbilical cord blood and matched sibling donors. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(1):134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furlan SN, et al. Systems analysis uncovers inflammatory Th/Tc17-driven modules during acute GVHD in monkey and human T cells. Blood. 2016;128(21):2568–2579. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-07-726547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soloviova K, Puliaiev M, Foster A, Via CS. The parent-into-F1 murine model in the study of lupus-like autoimmunity and CD8 cytotoxic T lymphocyte function. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;900:253–270. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-720-4_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim J, Cho HR, Kwon B. CD137 in chronic graft-versus-host disease. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1155:95–108. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0669-7_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reddy P, Negrin R, Hill GR. Mouse models of bone marrow transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14(1 suppl 1):129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hill GR, et al. Stem cell mobilization with G-CSF induces type 17 differentiation and promotes scleroderma. Blood. 2010;116(5):819–828. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-256495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexander KA, et al. CSF-1-dependant donor-derived macrophages mediate chronic graft-versus-host disease. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(10):4266–4280. doi: 10.1172/JCI75935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leveque-El Mouttie L, et al. Corruption of dendritic cell antigen presentation during acute GVHD leads to regulatory T-cell failure and chronic GVHD. Blood. 2016;128(6):794–804. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-11-680876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen X, Vodanovic-Jankovic S, Johnson B, Keller M, Komorowski R, Drobyski WR. Absence of regulatory T-cell control of TH1 and TH17 cells is responsible for the autoimmune-mediated pathology in chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2007;110(10):3804–3813. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-091074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dubovsky JA, et al. Ibrutinib treatment ameliorates murine chronic graft-versus-host disease. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(11):4867–4876. doi: 10.1172/JCI75328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flynn R, et al. Increased T follicular helper cells and germinal center B cells are required for cGVHD and bronchiolitis obliterans. Blood. 2014;123(25):3988–3998. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-03-562231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Srinivasan M, et al. Donor B-cell alloantibody deposition and germinal center formation are required for the development of murine chronic GVHD and bronchiolitis obliterans. Blood. 2012;119(6):1570–1580. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-364414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakoda Y, et al. Donor-derived thymic-dependent T cells cause chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2007;109(4):1756–1764. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-042853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perez VL, et al. Novel scoring criteria for the evaluation of ocular graft-versus-host disease in a preclinical allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation animal model. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(10):1765–1772. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ganguly S, et al. Donor CD4+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells are necessary for posttransplantation cyclophosphamide-mediated protection against GVHD in mice. Blood. 2014;124(13):2131–2141. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-10-525873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anderson BE, et al. Memory CD4+ T cells do not induce graft-versus-host disease. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(1):101–108. doi: 10.1172/JCI17601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson TM, O’Donnell PV, Fuchs EJ, Luznik L. Haploidentical bone marrow and stem cell transplantation: experience with post-transplantation cyclophosphamide. Semin Hematol. 2016;53(2):90–97. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bleakley M, et al. Outcomes of acute leukemia patients transplanted with naive T cell-depleted stem cell grafts. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(7):2677–2689. doi: 10.1172/JCI81229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hill GR, Crawford JM, Cooke KJ, Brinson YS, Pan L, Ferrara JLM. Total body irradiation and acute graft versus host disease. The role of gastrointestinal damage and inflammatory cytokines. Blood. 1997;90(8):3204–3213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kennedy GA, et al. Addition of interleukin-6 inhibition with tocilizumab to standard graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis after allogeneic stem-cell transplantation: a phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(13):1451–1459. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hill GR, Ferrara JL. The primacy of the gastrointestinal tract as a target organ of acute graft-versus-host disease: rationale for the use of cytokine shields in allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2000;95(9):2754–2759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramadan A, Paczesny S. Various forms of tissue damage and danger signals following hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Front Immunol. 2015;6:14. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kappel LW, et al. IL-17 contributes to CD4-mediated graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2009;113(4):945–952. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-172155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gartlan KH, et al. Tc17 cells are a proinflammatory, plastic lineage of pathogenic CD8+ T cells that induce GVHD without antileukemic effects. Blood. 2015;126(13):1609–1620. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-01-622662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burman AC, et al. IFNgamma differentially controls the development of idiopathic pneumonia syndrome and GVHD of the gastrointestinal tract. Blood. 2007;110(3):1064–1072. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-063982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu Y, et al. Prevention of GVHD while sparing GVL effect by targeting Th1 and Th17 transcription factor T-bet and RORγt in mice. Blood. 2011;118(18):5011–5020. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-340315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Varelias A, et al. Lung parenchyma-derived IL-6 promotes IL-17A-dependent acute lung injury after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2015;125(15):2435–2444. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-07-590232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimabukuro-Vornhagen A, Hallek MJ, Storb RF, von Bergwelt-Baildon MS. The role of B cells in the pathogenesis of graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2009;114(24):4919–4927. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-161638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sánchez-García J, et al. The impact of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease on normal and malignant B-lymphoid precursors after allogeneic stem cell transplantation for B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2006;91(3):340–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Storek J, Wells D, Dawson MA, Storer B, Maloney DG. Factors influencing B lymphopoiesis after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2001;98(2):489–491. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.2.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weinberg K, et al. Factors affecting thymic function after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2001;97(5):1458–1466. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.5.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scheller J, Chalaris A, Schmidt-Arras D, Rose-John S. The pro- and anti-inflammatory properties of the cytokine interleukin-6. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813(5):878–888. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hirano T. Interleukin 6 and its receptor: ten years later. Int Rev Immunol. 1998;16(3–4):249–284. doi: 10.3109/08830189809042997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Radojcic V, et al. STAT3 signaling in CD4+ T cells is critical for the pathogenesis of chronic sclerodermatous graft-versus-host disease in a murine model. J Immunol. 2010;184(2):764–774. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Flynn R, et al. Targeted Rho-associated kinase 2 inhibition suppresses murine and human chronic GVHD through a Stat3-dependent mechanism. Blood. 2016;127(17):2144–2154. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-10-678706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Serody JS, Hill GR. The IL-17 differentiation pathway and its role in transplant outcome. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18(1 suppl):S56–S61. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ferrara J. All pain, no gain: Tc17 phantoms in GVHD. Blood. 2015;126(13):1525–1526. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-08-661512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brüggen MC, et al. Diverse T-cell responses characterize the different manifestations of cutaneous graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2014;123(2):290–299. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-07-514372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Malard F, et al. Increased Th17/Treg ratio in chronic liver GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49(4):539–544. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Betts BC, et al. CD4+ T cell STAT3 phosphorylation precedes acute GVHD, and subsequent Th17 tissue invasion correlates with GVHD severity and therapeutic response. J Leukoc Biol. 2015;97(4):807–819. doi: 10.1189/jlb.5A1114-532RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lu SX, et al. STAT-3 and ERK 1/2 phosphorylation are critical for T-cell alloactivation and graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2008;112(13):5254–5258. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-147322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Clave E, et al. Tc1 clonal T cell expansion during chronic graft-versus-host disease-associated hypereosinophilia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20(5):739–742. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nishimori H, et al. Synthetic retinoid Am80 ameliorates chronic graft-versus-host disease by down-regulating Th1 and Th17. Blood. 2012;119(1):285–295. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-332478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fujiwara H, et al. Programmed death-1 pathway in host tissues ameliorates Th17/Th1-mediated experimental chronic graft-versus-host disease. J Immunol. 2014;193(5):2565–2573. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hakim FT, et al. Upregulation of IFN-inducible and damage-response pathways in chronic graft-versus-host disease. J Immunol. 2016;197(9):3490–3503. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gowdy KM, et al. Protective role of T-bet and Th1 cytokines in pulmonary graft-versus-host disease and peribronchiolar fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;46(2):249–256. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0131OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 64.Wicks IP, Roberts AW. Targeting GM-CSF in inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(1):37–48. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hume DA, MacDonald KP. Therapeutic applications of macrophage colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) and antagonists of CSF-1 receptor (CSF-1R) signaling. Blood. 2012;119(8):1810–1820. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-379214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hanash AM, et al. Interleukin-22 protects intestinal stem cells from immune-mediated tissue damage and regulates sensitivity to graft versus host disease. Immunity. 2012;37(2):339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lindemans CA, et al. Interleukin-22 promotes intestinal-stem-cell-mediated epithelial regeneration. Nature. 2015;528(7583):560–564. doi: 10.1038/nature16460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhao K, et al. Interleukin-22 aggravates murine acute graft-versus-host disease by expanding effector T cell and reducing regulatory T cell. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2014;34(9):707–715. doi: 10.1089/jir.2013.0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhao K, et al. IL-22 promoted CD3+ T cell infiltration by IL-22R induced STAT3 phosphorylation in murine acute graft versus host disease target organs after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016;39:383–388. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Couturier M, et al. IL-22 deficiency in donor T cells attenuates murine acute graft-versus-host disease mortality while sparing the graft-versus-leukemia effect. Leukemia. 2013;27(7):1527–1537. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lamarthée B, et al. Donor interleukin-22 and host type I interferon signaling pathway participate in intestinal graft-versus-host disease via STAT1 activation and CXCL10. Mucosal Immunol. 2016;9(2):309–321. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen X, et al. Blockade of interleukin-6 signaling augments regulatory T-cell reconstitution and attenuates the severity of graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2009;114(4):891–900. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-197178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tawara I, et al. Interleukin-6 modulates graft-versus-host responses after experimental allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(1):77–88. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ueno H, Banchereau J, Vinuesa CG. Pathophysiology of T follicular helper cells in humans and mice. Nat Immunol. 2015;16(2):142–152. doi: 10.1038/ni.3054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Patriarca F, et al. The development of autoantibodies after allogeneic stem cell transplantation is related with chronic graft-vs-host disease and immune recovery. Exp Hematol. 2006;34(3):389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jin H, et al. Antibodies from donor B cells perpetuate cutaneous chronic graft-versus-host disease in mice. Blood. 2016;127(18):2249–2260. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-09-668145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Miklos DB, et al. Antibody responses to H-Y minor histocompatibility antigens correlate with chronic graft-versus-host disease and disease remission. Blood. 2005;105(7):2973–2978. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zorn E, et al. Minor histocompatibility antigen DBY elicits a coordinated B and T cell response after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. J Exp Med. 2004;199(8):1133–1142. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yang R, et al. IL-6 promotes the differentiation of a subset of naive CD8+ T cells into IL-21-producing B helper CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2016;213(11):2281–2291. doi: 10.1084/jem.20160417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Greinix HT, et al. Elevated numbers of immature/transitional CD21– B lymphocytes and deficiency of memory CD27+ B cells identify patients with active chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14(2):208–219. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Allen JL, et al. B cells from patients with chronic GVHD are activated and primed for survival via BAFF-mediated pathways. Blood. 2012;120(12):2529–2536. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-438911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vincent FB, Morand EF, Schneider P, Mackay F. The BAFF/APRIL system in SLE pathogenesis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10(6):365–373. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fujii H, et al. Biomarkers in newly diagnosed pediatric-extensive chronic graft-versus-host disease: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Blood. 2008;111(6):3276–3285. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-106286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sarantopoulos S, et al. High levels of B-cell activating factor in patients with active chronic graft-versus-host disease. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(20):6107–6114. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sarantopoulos S, et al. Altered B-cell homeostasis and excess BAFF in human chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2009;113(16):3865–3874. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-177840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ohkura N, Kitagawa Y, Sakaguchi S. Development and maintenance of regulatory T cells. Immunity. 2013;38(3):414–423. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Roncarolo MG, Bacchetta R, Bordignon C, Narula S, Levings MK. Type 1 T regulatory cells. Immunol Rev. 2001;182:68–79. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065X.2001.1820105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhang P, et al. Induced regulatory T cells promote tolerance when stabilized by rapamycin and IL-2 in vivo. J Immunol. 2013;191(10):5291–5303. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Matsuoka K, et al. Altered regulatory T cell homeostasis in patients with CD4+ lymphopenia following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(5):1479–1493. doi: 10.1172/JCI41072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Alho AC, et al. Unbalanced recovery of regulatory and effector T cells after allogeneic stem cell transplantation contributes to chronic GVHD. Blood. 2016;127(5):646–657. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-10-672345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.McDonald-Hyman C, et al. Therapeutic regulatory T-cell adoptive transfer ameliorates established murine chronic GVHD in a CXCR5-dependent manner. Blood. 2016;128(7):1013–1017. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-05-715896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Coghill JM, et al. CC chemokine receptor 8 potentiates donor Treg survival and is critical for the prevention of murine graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2013;122(5):825–836. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-435735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Markey KA, et al. Immune insufficiency during GVHD is due to defective antigen presentation within dendritic cell subsets. Blood. 2012;119(24):5918–5930. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-398164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Koreth J, et al. Interleukin-2 and regulatory T cells in graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(22):2055–2066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Matsuoka K, et al. Low-dose interleukin-2 therapy restores regulatory T cell homeostasis in patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(179):179ra43. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Koreth J, et al. Efficacy, durability, and response predictors of low-dose interleukin-2 therapy for chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2016;128(1):130–137. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-02-702852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hirakawa M, et al. Low-dose IL-2 selectively activates subsets of CD4(+) Tregs and NK cells. JCI Insight. 2016;1(18):e89278. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.89278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Groux H, et al. A CD4+ T-cell subset inhibits antigen-specific T-cell responses and prevents colitis. Nature. 1997;389(6652):737–742. doi: 10.1038/39614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Morris ES, et al. Donor treatment with pegylated G-CSF augments the generation of IL-10-producing regulatory T cells and promotes transplantation tolerance. Blood. 2004;103(9):3573–3581. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rowe V, et al. Host B cells produce IL-10 following TBI and attenuate acute GVHD after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2006;108(7):2485–2492. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-016063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rutella S, et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor promotes the generation of regulatory DC through induction of IL-10 and IFN-α. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34(5):1291–1302. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tawara I, et al. Donor- but not host-derived interleukin-10 contributes to the regulation of experimental graft-versus-host disease. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;91(4):667–675. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1011510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.MacDonald KP, et al. Cytokine expanded myeloid precursors function as regulatory antigen-presenting cells and promote tolerance through IL-10-producing regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2005;174(4):1841–1850. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.de Masson A, et al. CD24(hi)CD27+ and plasmablast-like regulatory B cells in human chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2015;125(11):1830–1839. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-09-599159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Khoder A, et al. Regulatory B cells are enriched within the IgM memory and transitional subsets in healthy donors but are deficient in chronic GVHD. Blood. 2014;124(13):2034–2045. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-571125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gregori S, Goudy KS, Roncarolo MG. The cellular and molecular mechanisms of immuno-suppression by human type 1 regulatory T cells. Front Immunol. 2012;3:30. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pan L, Delmonte J, Jr, Jalonen CK, Ferrara JL. Pretreatment of donor mice with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor polarizes donor T lymphocytes toward type-2 cytokine production and reduces severity of experimental graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 1995;86(12):4422–4429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Arpinati M, Green CL, Heimfeld S, Heuser JE, Anasetti C. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor mobilizes T helper 2-inducing dendritic cells. Blood. 2000;95(8):2484–2490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.MacDonald KP, et al. Modification of T cell responses by stem cell mobilization requires direct signaling of the T cell by G-CSF and IL-10. J Immunol. 2014;192(7):3180–3189. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Huber S, et al. Th17 cells express interleukin-10 receptor and are controlled by Foxp3– and Foxp3+ regulatory CD4+ T cells in an interleukin-10-dependent manner. Immunity. 2011;34(4):554–565. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chen WF, Zlotnik A. IL-10: a novel cytotoxic T cell differentiation factor. J Immunol. 1991;147(2):528–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Blazar BR, Taylor PA, Smith S, Vallera DA. Interleukin-10 administration decreases survival in murine recipients of major histocompatibility complex disparate donor bone marrow grafts. Blood. 1995;85(3):842–851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Blazar BR, et al. Interleukin-10 dose-dependent regulation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell-mediated graft-versus-host disease. Transplantation. 1998;66(9):1220–1229. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199811150-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Gagliani N, et al. Coexpression of CD49b and LAG-3 identifies human and mouse T regulatory type 1 cells. Nat Med. 2013;19(6):739–746. doi: 10.1038/nm.3179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Roncarolo MG, Gregori S, Bacchetta R, Battaglia M. Tr1 cells and the counter-regulation of immunity: natural mechanisms and therapeutic applications. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2014;380:39–68. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-43492-5_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bacchetta R, et al. Immunological outcome in haploidentical-HSC transplanted patients treated with IL-10-anergized donor T cells. Front Immunol. 2014;5:16. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Bourette RP, Myles GM, Choi JL, Rohrschneider LR. Sequential activation of phoshatidylinositol 3-kinase and phospholipase C-gamma2 by the M-CSF receptor is necessary for differentiation signaling. EMBO J. 1997;16(19):5880–5893. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.19.5880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Munugalavadla V, Borneo J, Ingram DA, Kapur R. p85α subunit of class IA PI-3 kinase is crucial for macrophage growth and migration. Blood. 2005;106(1):103–109. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-4041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Mancini A, Koch A, Whetton AD, Tamura T. The M-CSF receptor substrate and interacting protein FMIP is governed in its subcellular localization by protein kinase C-mediated phosphorylation, and thereby potentiates M-CSF-mediated differentiation. Oncogene. 2004;23(39):6581–6589. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.MacDonald KP, et al. An antibody against the colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor depletes the resident subset of monocytes and tissue- and tumor-associated macrophages but does not inhibit inflammation. Blood. 2010;116(19):3955–3963. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-266296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.MacDonald KP, et al. The colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor is expressed on dendritic cells during differentiation and regulates their expansion. J Immunol. 2005;175(3):1399–1405. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sarrazin S, et al. MafB restricts M-CSF-dependent myeloid commitment divisions of hematopoietic stem cells. Cell. 2009;138(2):300–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wang ZE, Myles GM, Brandt CS, Lioubin MN, Rohrschneider L. Identification of the ligand-binding regions in the macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor extracellular domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13(9):5348–5359. doi: 10.1128/MCB.13.9.5348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Nandi S, et al. The CSF-1 receptor ligands IL-34 and CSF-1 exhibit distinct developmental brain expression patterns and regulate neural progenitor cell maintenance and maturation. Dev Biol. 2012;367(2):100–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Yagiz K, Rittling SR. Both cell-surface and secreted CSF-1 expressed by tumor cells metastatic to bone can contribute to osteoclast activation. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315(14):2442–2452. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Huynh D, et al. Colony stimulating factor-1 dependence of paneth cell development in the mouse small intestine. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(1):136–144. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Lee AW, States DJ. Colony-stimulating factor-1 requires PI3-kinase-mediated metabolism for proliferation and survival in myeloid cells. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13(11):1900–1914. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Melcher M, Unger B, Schmidt U, Rajantie IA, Alitalo K, Ellmeier W. Essential roles for the Tec family kinases Tec and Btk in M-CSF receptor signaling pathways that regulate macrophage survival. J Immunol. 2008;180(12):8048–8056. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.12.8048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Stanley ER, Chitu V. CSF-1 receptor signaling in myeloid cells. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6(6):a021857. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a021857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Blazar BR, et al. CD47 (integrin-associated protein) engagement of dendritic cell and macrophage counterreceptors is required to prevent the clearance of donor lymphohematopoietic cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194(4):541–549. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Hashimoto D, et al. Pretransplant CSF-1 therapy expands recipient macrophages and ameliorates GVHD after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Exp Med. 2011;208(5):1069–1082. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Melino M, et al. Spatiotemporal characterization of the cellular and molecular contributors to liver fibrosis in a murine hepatotoxic-injury model. Am J Pathol. 2016;186(3):524–538. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ge S, et al. Interleukin 17 receptor A modulates monocyte subsets and macrophage generation in vivo. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85461. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Shahrara S, Pickens SR, Dorfleutner A, Pope RM. IL-17 induces monocyte migration in rheumatoid arthritis. J Immunol. 2009;182(6):3884–3891. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Erbel C, et al. IL-17A influences essential functions of the monocyte/macrophage lineage and is involved in advanced murine and human atherosclerosis. J Immunol. 2014;193(9):4344–4355. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Goumans MJ, Liu Z, ten Dijke P. TGF-β signaling in vascular biology and dysfunction. Cell Res. 2009;19(1):116–127. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Grotendorst GR, Smale G, Pencev D. Production of transforming growth factor β by human peripheral blood monocytes and neutrophils. J Cell Physiol. 1989;140(2):396–402. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041400226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Shull MM, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-β1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature. 1992;359(6397):693–699. doi: 10.1038/359693a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Annes JP, Munger JS, Rifkin DB. Making sense of latent TGFbeta activation. J Cell Sci. 2003;116(pt 2):217–224. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Kang JS, Liu C, Derynck R. New regulatory mechanisms of TGF-β receptor function. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19(8):385–394. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Shi Y, Massagué J. Mechanisms of TGF-β signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell. 2003;113(6):685–700. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00432-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Zhang YE. Non-Smad pathways in TGF-β signaling. Cell Res. 2009;19(1):128–139. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Hocevar BA, Howe PH. Analysis of TGF-β-mediated synthesis of extracellular matrix components. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;142:55–65. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-053-5:55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.McCormick LL, Zhang Y, Tootell E, Gilliam AC. Anti-TGF-β treatment prevents skin and lung fibrosis in murine sclerodermatous graft-versus-host disease: a model for human scleroderma. J Immunol. 1999;163(10):5693–5699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Zhang Y, McCormick LL, Gilliam AC. Latency-associated peptide prevents skin fibrosis in murine sclerodermatous graft-versus-host disease, a model for human scleroderma. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121(4):713–719. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Banovic T, et al. TGF-β in allogeneic stem cell transplantation: friend or foe? Blood. 2005;106(6):2206–2214. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Wu JM, Thoburn CJ, Wisell J, Farmer ER, Hess AD. CD20, AIF-1, and TGF-β in graft-versus-host disease: a study of mRNA expression in histologically matched skin biopsies. Mod Pathol. 2010;23(5):720–728. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Chopra R, Anastassiades T. Specificity and synergism of polypeptide growth factors in stimulating the synthesis of proteoglycans and a novel high molecular weight anionic glycoprotein by articular chondrocyte cultures. J Rheumatol. 1998;25(8):1578–1584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Liem LM, Fibbe WE, van Houwelingen HC, Goulmy E. Serum transforming growth factor-β1 levels in bone marrow transplant recipients correlate with blood cell counts and chronic graft-versus-host disease. Transplantation. 1999;67(1):59–65. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199901150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Kyrcz-Krzemień S, Helbig G, Zielińska P, Markiewicz M. The kinetics of mRNA transforming growth factor β1 expression and its serum concentration in graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic hemopoietic stem cell transplantation for myeloid leukemias. Med Sci Monit. 2011;17(6):CR322–CR328. doi: 10.12659/MSM.881804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Svegliati S, et al. Stimulatory autoantibodies to PDGF receptor in patients with extensive chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2007;110(1):237–241. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-071043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Spies-Weisshart B, Schilling K, Böhmer F, Hochhaus A, Sayer HG, Scholl S. Lack of association of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor autoantibodies and severity of chronic graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;139(8):1397–1404. doi: 10.1007/s00432-013-1451-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Olivieri A, et al. Imatinib for refractory chronic graft-versus-host disease with fibrotic features. Blood. 2009;114(3):709–718. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-204156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Sanchez-Ortega I, et al. Dasatinib as salvage therapy for steroid refractory and imatinib resistant or intolerant sclerotic chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18(2):318–323. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Kulkarni AB, et al. Transforming growth factor beta 1 null mutation in mice causes excessive inflammatory response and early death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(2):770–774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Lucas PJ, Kim SJ, Melby SJ, Gress RE. Disruption of T cell homeostasis in mice expressing a T cell-specific dominant negative transforming growth factor beta II receptor. J Exp Med. 2000;191(7):1187–1196. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.7.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]