Abstract

BACKGROUND. The risk of advanced fibrosis in first-degree relatives of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and cirrhosis (NAFLD-cirrhosis) is unknown and needs to be systematically quantified. We aimed to prospectively assess the risk of advanced fibrosis in first-degree relatives of probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis.

METHODS. This is a cross-sectional analysis of a prospective cohort of 26 probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis and 39 first-degree relatives. The control population included 69 community-dwelling twin, sib-sib, or parent-offspring pairs (n = 138), comprising 69 individuals randomly ascertained to be without evidence of NAFLD and 69 of their first-degree relatives. The primary outcome was presence of advanced fibrosis (stage 3 or 4 fibrosis). NAFLD was assessed clinically and quantified by MRI proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF). Advanced fibrosis was diagnosed by liver stiffness greater than 3.63 kPa using magnetic resonance elastography (MRE).

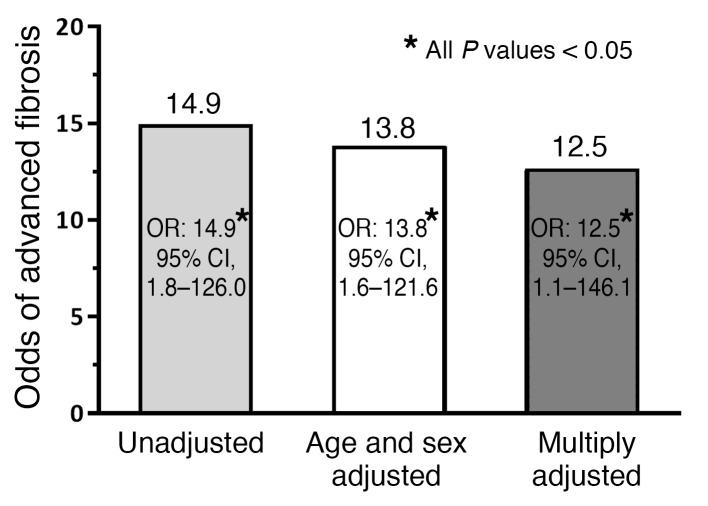

RESULTS. The prevalence of advanced fibrosis in first-degree relatives of probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis was significantly higher than that in the control population (17.9% vs. 1.4%, P = 0.0032). Compared with controls, the odds of advanced fibrosis among the first-degree relatives of probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis were odds ratio 14.9 (95% CI, 1.8–126.0, P = 0.0133). Even after multivariable adjustment by age, sex, Hispanic ethnicity, BMI, and diabetes status, the risk of advanced fibrosis remained both statistically and clinically significant (multivariable-adjusted odds ratio 12.5; 95% CI, 1.1–146.1, P = 0.0438).

CONCLUSION. Using a well-phenotyped familial cohort, we demonstrated that first-degree relatives of probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis have a 12 times higher risk of advanced fibrosis. Advanced fibrosis screening may be considered in first-degree relatives of NAFLD-cirrhosis patients.

TRIAL REGISTRATION. UCSD IRB: 140084.

FUNDING. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, NIH.

Keywords: Gastroenterology, Hepatology

Introduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common cause of liver disease in the United States (1, 2). Recent studies have suggested that presence of fibrosis portends a worse prognosis in NAFLD (3–5). The risk of death from liver disease is substantially increased in patients with advanced fibrosis who have either bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis–related cirrhosis represents the pathologic endpoint of NAFLD, characterized by extensive fibrosis with regenerative nodule formation (6, 7), and it is currently the second most common indication for liver transplantation in the United States (8–10).

Previous seminal studies have suggested that there is familial clustering of NAFLD. Abdelmalek and colleagues compared 20 patients with NAFLD and 20 controls and obtained history of NAFLD and other metabolic traits and found that there was familial clustering of insulin resistance within families with NAFLD (11). Willner and colleagues conducted a retrospective chart review of 90 patients with NAFLD and documented familial clustering that was seen in 18% of patients in this cohort, suggesting that it may be heritable (12). NAFLD has been shown to be a heritable trait (13–15). More recently, using twin-study design, we demonstrated that both hepatic steatosis and hepatic fibrosis are heritable traits, and also showed that hepatic steatosis and fibrosis have significant shared gene effects (16, 17). The emerging familial association with NAFLD suggests a plausibility that cirrhosis related to NAFLD may also have a strong familial association.

The presence of advanced fibrosis in NAFLD is significantly associated with overall mortality, liver transplantation, and liver-related events in long-term longitudinal studies (3, 5). However, there are limited prospective data regarding the quantitative risk of advanced fibrosis in first-degree relatives of probands with NAFLD and cirrhosis (NAFLD-cirrhosis) (18). The risk of advanced fibrosis in the first-degree relatives of patients with NAFLD-cirrhosis is unknown and needs to be systematically quantified.

The aim of this study was to prospectively assess the risk of advanced fibrosis in first-degree relatives of probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis. We hypothesized that the prevalence of advanced fibrosis is higher in the first-degree relatives of probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis compared with a control population. Systematic screening for advanced fibrosis in first-degree relatives of probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis may impact future screening guidelines for advanced NAFLD.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the familial NAFLD-cirrhosis cohort.

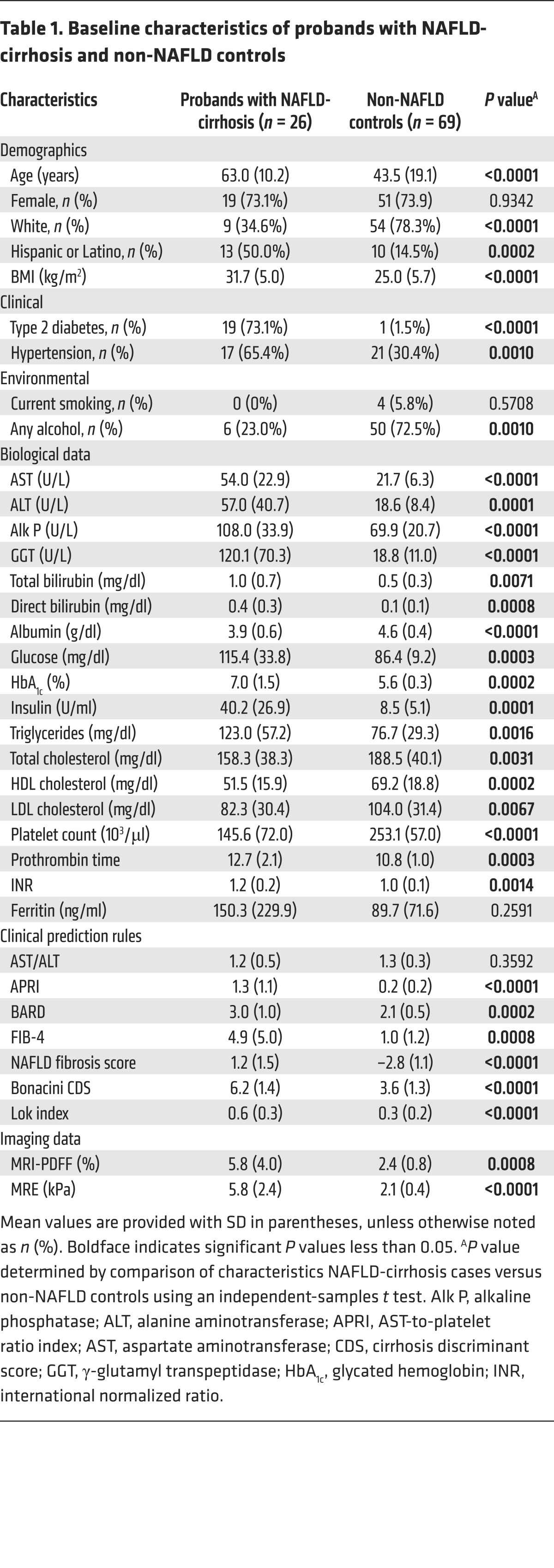

This prospective study included 26 probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis and 39 of their first-degree relatives. Twenty probands had biopsy-proven cirrhosis, and 6 probands had cirrhosis by imaging criteria. The detailed derivation of the study cohort is shown in Supplemental Figure 1 (supplemental material available online with this article; https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI93465DS1). The probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis had a mean age (±SD) of 63.0 (±10.2) years and a mean BMI (±SD) of 31.7 (±5.0) kg/m2, and 73.1% had type 2 diabetes. The detailed demographic, biochemical, and imaging data of probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis compared with non-NAFLD controls are provided in Table 1. The first-degree relatives of the probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis had a mean age (±SD) of 48.2 (±16.9) years and a BMI (±SD) of 31.0 (±5.9) kg/m2, and 15.4% had type 2 diabetes.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis and non-NAFLD controls.

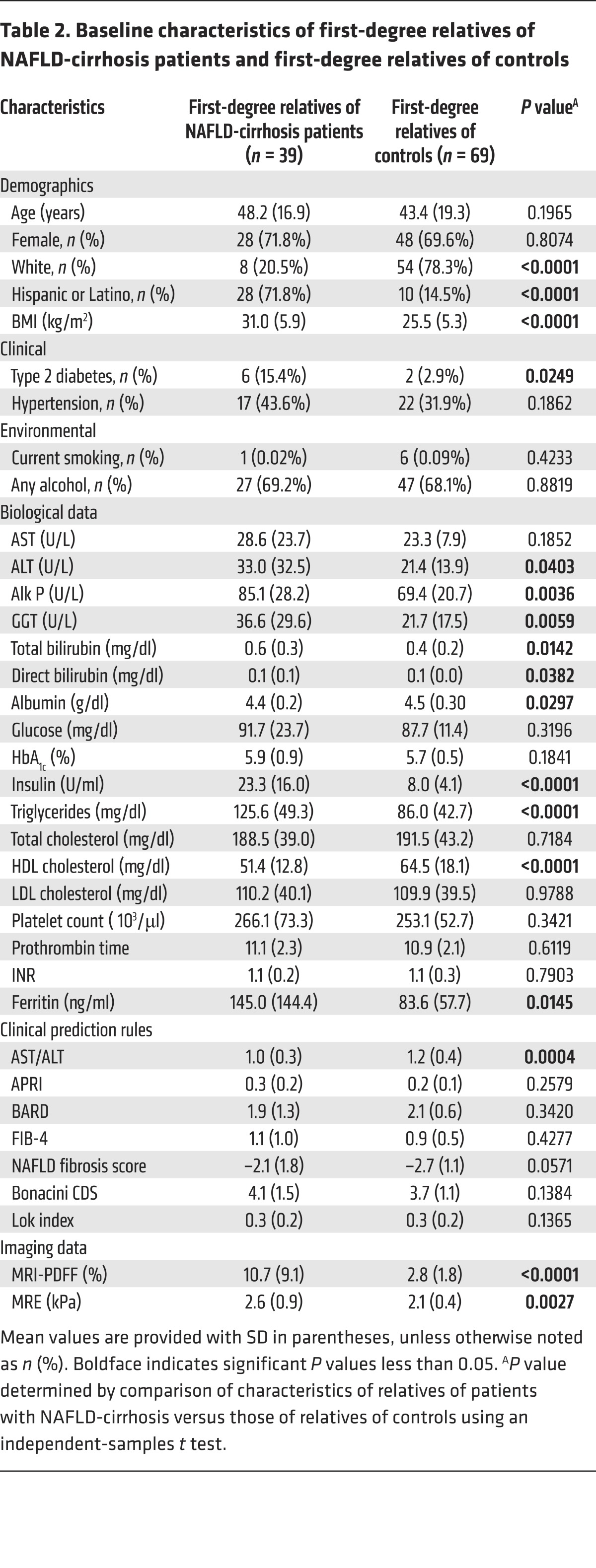

The demographic, biochemical, and imaging data of first-degree relatives of probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis compared with those of non-NAFLD controls are detailed in Table 2. Compared with first-degree relatives of controls, first-degree relatives of probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis had a higher BMI (31.0 kg/m2 vs. 25.5 kg/m2, P < 0.0001), and were more likely to be diabetic (15.4% vs. 2.9%, P < 0.0249). As expected, the first-degree relatives of probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis had also a higher liver fat content on MRI proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF) (10.7% vs. 2.8%, P < 0.0001) than first-degree relatives of controls.

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of first-degree relatives of NAFLD-cirrhosis patients and first-degree relatives of controls.

Prevalence of NAFLD and advanced fibrosis in the familial NAFLD-cirrhosis cohort.

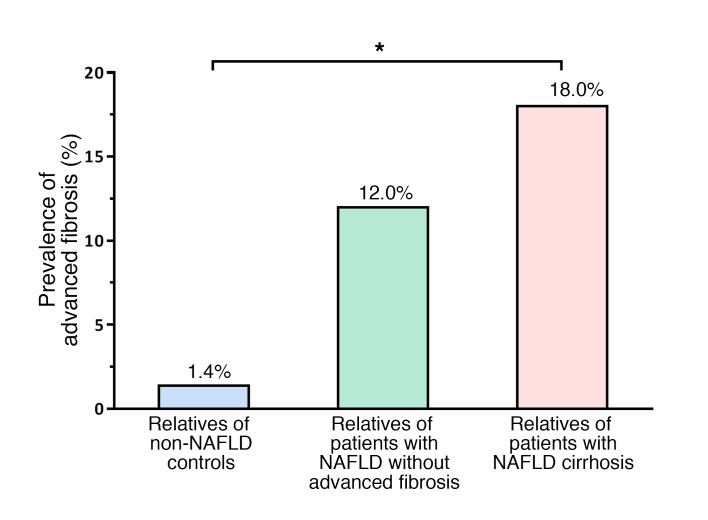

The prevalence of NAFLD was significantly higher in first-degree relatives of probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis versus first-degree relatives of controls: 74% versus 8.7% (P < 0.001), respectively. Among 39 first-degree relatives of probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis, 29 (74%) were found to have NAFLD, and 7 (18%) had advanced fibrosis. The prevalence of advanced fibrosis increased in a dose-dependent manner based on the phenotype of the probands. The prevalence of advanced fibrosis in the first-degree relatives of probands with non-NAFLD versus NAFLD without advanced fibrosis versus NAFLD with cirrhosis was 1.4% versus 12% versus 18%, respectively, which was both clinically and statistically significant (P for trend less than 0.003 determined using a Cochran-Armitage test) (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) measurements illustrating the distribution of liver stiffness in the first-degree relatives of patients with NAFLD-cirrhosis and in the first-degree relatives of non-NAFLD controls are represented in Supplemental Figure 2.

Figure 1. Prevalence of advanced fibrosis in first-degree relatives of patients with NAFLD-cirrhosis and NAFLD without advanced fibrosis and non-NAFLD controls.

The prevalence of advanced fibrosis assessed by MRE (>3.63 kPa), expressed as percentage of individuals with advanced fibrosis among the first-degree relatives of probands with non-NAFLD (total n = 69; blue bar), NAFLD without advanced fibrosis (total n = 25; green bar), and NAFLD with cirrhosis (total n = 39; pink bar), was 1.4%, 12%, and 18%, respectively, which was both clinically and statistically significant (*P < 0.003 by Cochran-Armitage test for trend).

Odds of advanced fibrosis in first-degree relatives with NAFLD-cirrhosis.

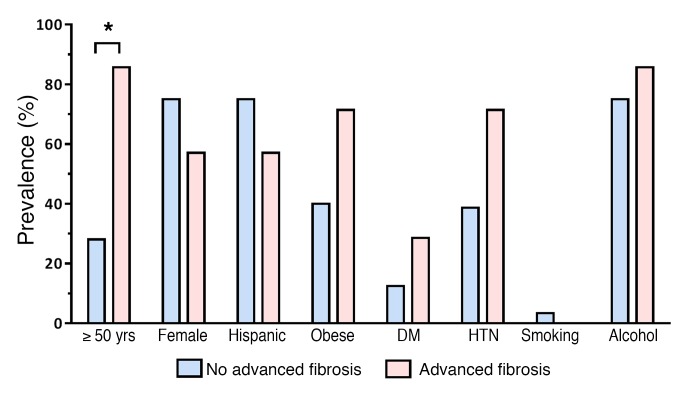

Compared with the control population, the odds ratio (OR) of having advanced fibrosis among first-degree relatives of probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis was 14.9 (95% CI, 1.8–126.0, P = 0.0133). The detailed differences between factors associated with NAFLD as well as fibrosis (age, sex, Hispanic ethnicity, BMI, and diabetes status) in the first-degree relatives of patients with NAFLD-cirrhosis are represented in Figure 2. The risk of advanced fibrosis remained both statistically and clinically significant even after adjustment for age, sex, Hispanic ethnicity, BMI, and diabetes status with a multivariable-adjusted OR of 12.5 (95% CI, 1.1–146.1, P = 0.0438) (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Distribution of factors associated with NAFLD and fibrosis in first-degree relatives of patients with NAFLD-cirrhosis.

The prevalence of each factor is expressed as percentage of first-degree relatives of patients with NAFLD-cirrhosis and without advanced fibrosis (blue bars; total n = 32) and percentage of first-degree relatives of patients with NAFLD-cirrhosis and advanced fibrosis (pink bars; total n = 7). DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension. *P < 0.05 by χ2 test.

Figure 3. Risk of advanced fibrosis in first-degree relatives of NAFLD-cirrhosis patients.

Compared with non-NAFLD controls (n = 69), the OR of cirrhosis in first-degree relatives of NAFLD-cirrhosis patients (n = 39) was 14.9 (95% CI, 1.8–126.0, P = 0.0133). The cirrhosis risk remained statistically and clinically significant after adjustment for age, sex, Hispanic ethnicity (no/yes), BMI, and diabetes, with a multivariable-adjusted OR of 12.5 (95% CI, 1.1–146.1, P = 0.0438). ORs were assessed by unadjusted and multivariable-adjusted logistic regression analyses.

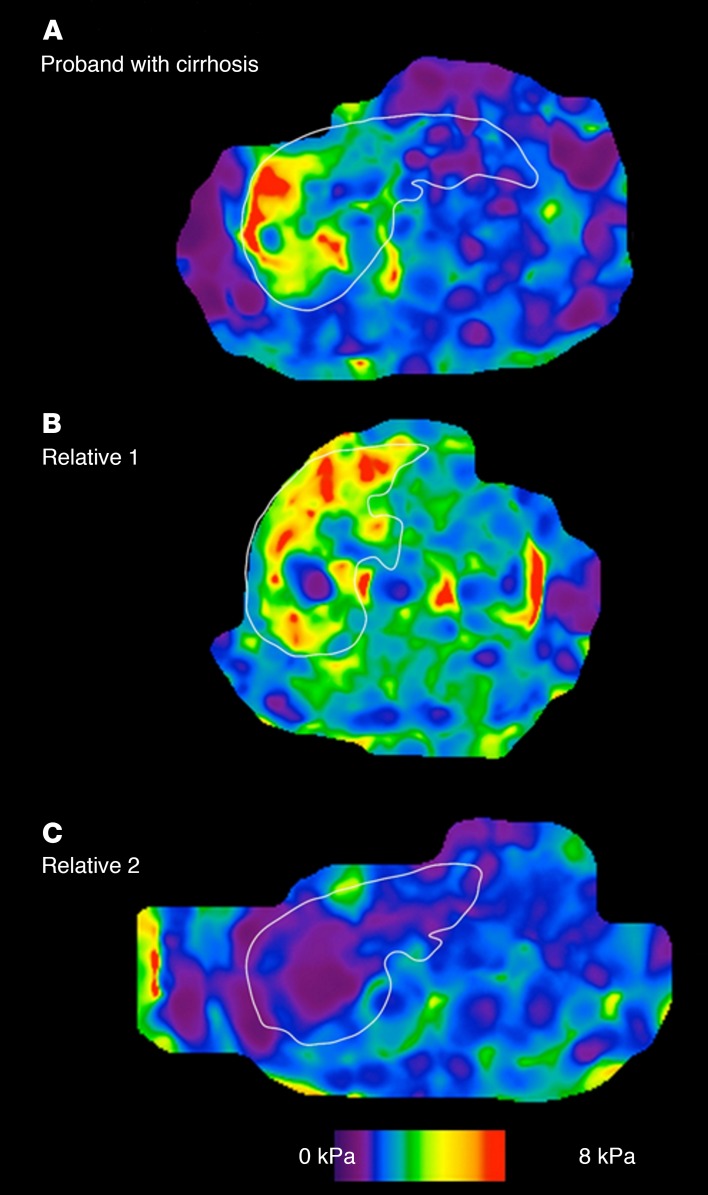

We show an example of a proband with NAFLD-cirrhosis (Figure 4A) and one of the first-degree relatives with NAFLD-cirrhosis (Figure 4B) as well as another first-degree relative without any fibrosis (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Representative MRE in a proband with NAFLD-cirrhosis and her first-degree relatives.

Representative MRE map of (A) a 73-year-old female with cirrhosis diagnosed with MRE of 4.36 kPa, (B) her 69-year-old brother with cirrhosis diagnosed with MRE of 4.3 kPa, and (C) her 66-year-old sister without cirrhosis excluded with MRE of 1.82.

Sensitivity analyses.

We conducted sensitivity analysis to further assess whether there was a consistent increased risk of cirrhosis in first-degree relatives of NAFLD-cirrhosis patients using the estimated prevalence of cirrhosis in the general population in the United States (19, 20). The risk of having cirrhosis among first-degree relatives of NAFLD-cirrhosis patients remained significant and was even higher with an OR of 80.85 (95% CI, 32.85–198.99, P < 0.0001) using a prevalence of cirrhosis of 0.27% reported by Shuppan et al. (20) and with an OR of 145.63 (95% CI, 55.65–381.06, P < 0.0001) using a prevalence of 0.15% reported by Scaglione et al. (19).

PNPLA3 p.I148M genotype.

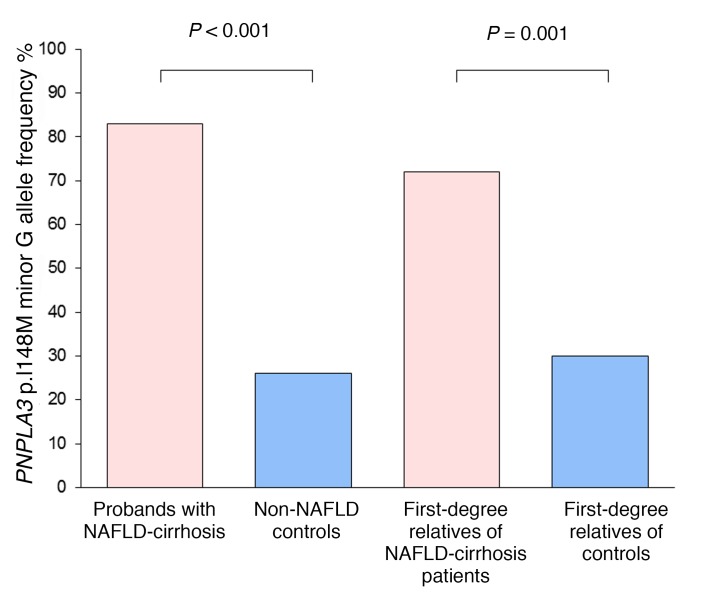

The allele frequency of patatin-like phospholipase domain–containing 3 (PNPLA3) p.I148M was analyzed in a subgroup of 119 patients of this cohort. The allele frequency of the minor variant G was significantly higher in the probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis group compared with non-NAFLD controls (0.83 vs. 0.26, P = 0.0002) (Figure 5). In addition, the allele frequency of the minor variant G in our non-NAFLD control group is similar to the allele frequency in the general population of 0.233 from the HapMap Project. The allele frequency of the minor variant G is also logically significantly overrepresented in the first-degree relatives of NAFLD-cirrhosis patients compared with first-degree relatives of controls (0.70 vs. 0.30, P = 0.0001) (Figure 5). However, the distribution of the minor variant G was not significantly different between first-degree relatives of NAFLD-cirrhosis patients with and without advanced fibrosis.

Figure 5. PNPLA3 p.I148M minor G allele frequencies.

The allele frequency of PNPLA3 p.I148M minor variant G is expressed as percentage of minor allele G in probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis (pink bar; total n = 12 alleles) compared with non-NAFLD controls (blue bar; total n = 92 alleles) and percentage of first-degree relatives of patients with NAFLD-cirrhosis (pink bar; total n = 46 alleles) compared with first-degree relatives of controls (blue bar; total n = 88 alleles). P value was determined using a Fisher exact test or a χ2 test when appropriate.

Discussion

Main findings.

Using a uniquely well-phenotyped familial cohort, we demonstrate that first-degree relatives of probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis have a 12 times higher risk of advanced fibrosis compared with the first-degree relatives of non-NAFLD controls. This cross-sectional analysis of a prospectively recruited cohort provides quantitative estimates of the risk of advanced fibrosis among family members of patients with NAFLD-cirrhosis. These data provide preliminary but high-quality evidence that screening for advanced fibrosis in first-degree relatives of patients with NAFLD-cirrhosis would be beneficial and thus may be considered. Further studies are needed if genetic factors or environmental risk factors or biomarkers are to be utilized to predict the risk of advanced fibrosis within first-degree relatives of probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis.

Context of published literature.

Several studies have shown that NAFLD may be heritable (11, 15–17). Recently, hepatic fibrosis has also been shown to be a heritable trait, suggesting that NAFLD-related cirrhosis may also run in families. Previous seminal studies have shown that there is familial aggregation of NAFLD and insulin resistance. However, previous familial studies were retrospective in nature and were based on either chart review or self-report regarding family history status. However, to our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate a significantly increased risk of advanced fibrosis in first-degree relatives in a cohort of familial cirrhosis including well-phenotyped probands with proven cirrhosis and their first-degree relatives using accurate quantification of liver steatosis and liver fibrosis by advanced and accurate MRI-based imaging modalities.

The susceptibility traits of NAFLD are likely to be multifactorial, including environmental, lifestyle behavior, genetic, and epigenetic (21). While studying environment and nutritional behavior remains challenging, the genetic role of the variants located on the genes PNPLA3 (22–24) and transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2 (TM6SF2) (25) has been shown to modify the risks of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis. In addition, GWAS has identified other genetic variants associated with features of hepatic histology in patients with NAFLD (26). In addition, serum miRNA expression has been shown to correlate with liver steatosis in a twin study with a heritable trait (27) and could also account for familial cirrhosis. However, the causal fibrosis-related mechanism of these SNPs or miRNAs remains unknown, and other genetic or epigenetic pathways implicated in the development of fibrosis remain to be elucidated. Larger studies would be needed to better understand the role of these mechanisms in increasing the risk of advanced fibrosis in family members of NAFLD-cirrhosis patients.

Strengths and limitations.

There are several notable strengths of this study, including the prospectively recruited study cohort, systematic and standardized liver disease assessment of all participants and controls, and detailed advanced MRI of the liver. The use of MRI-PDFF allowed for an accurate, noninvasive, and quantitative assessment of hepatic steatosis, and the use of MRE allowed for an accurate, noninvasive, and quantitative assessment of hepatic fibrosis.

However, we acknowledge the following limitations of this study. This is a single-center study that was conducted at a tertiary care center using advanced MRI assessment that may not be routinely available at other sites. In addition, this is a cross-sectional study, and therefore long-term outcomes such as survival or development of hepatocellular carcinoma could not be assessed. Liver biopsy assessment could not be performed, and instead we used the most accurate noninvasive modalities for the assessment of hepatic steatosis and hepatic fibrosis (28, 29). This study screened asymptomatic first-degree relatives of patients with NAFLD-cirrhosis, and controls with no suspected liver disease. Exposing the study population to the risks associated with a liver biopsy assessment, including pain, bleeding, and, in rare cases, death, would not be justifiable and appropriate. We acknowledge that there are additional environmental risk factors that may be influencing disease penetrance but may not have been adequately examined in this proof-of-concept study. Finally, further studies are needed to dissect out the interplay between environmental risk factors and genetic risk factors of disease susceptibility in patients with a family history of NAFLD-cirrhosis. Despite these limitations, we believe that this study provides important data that require validation in larger studies to then change clinical practice guidelines to screen first-degree relatives of patients with NAFLD-cirrhosis.

Implications for clinical care and future research.

This pilot study attempts to provide a quantitative risk estimate of the prevalence of advanced fibrosis and potentially the need for screening of the first-degree relatives of patients with NAFLD-cirrhosis. Further longitudinal studies would be needed to assess the risk of long-term outcomes in patients who are diagnosed with advanced fibrosis using such screening strategies versus no screening. In addition, comparative cost-effectiveness studies are needed to compare the role of various modalities, such as MRE, ultrasound-based shear wave elastography, acoustic radiation force impulse imaging, and virtual contrast transient elastography, in screening for advanced fibrosis in multicenter settings. In addition, it would be noteworthy to further explore the role of environmental, genetic, or epigenetic factors in the risk of advanced fibrosis and long-term outcomes in patients with NAFLD.

Finally, these findings provide new evidence regarding the need for systematic screening for advanced fibrosis in the first-degree relatives of patients with NAFLD-cirrhosis in routine clinical practice. These data may impact and potentially change clinical practice in increasing awareness of advanced fibrosis in NAFLD in high-risk populations such as those with a first-degree relative with NAFLD-cirrhosis. Further studies are needed to determine the interval for surveillance after initial screening. The clinical implications of this study are potentially significant, as earlier detection of cirrhosis would perhaps lead to earlier initiation of hepatocellular carcinoma screening and surveillance. Once a small suspected hepatocellular carcinoma is recognized via these screening programs, more timely referrals for liver transplant could be done, and this possibly may improve survival. Future studies are needed to explore potential risks versus benefits of screening for advanced fibrosis in first-degree relatives of patients with NAFLD-cirrhosis.

Methods

Study participants and design.

This is a cross-sectional analysis of a prospectively recruited cohort of probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis and their first-degree relatives enrolled between February 2013 and March 2016. All patients were invited for a clinical research visit and underwent a standardized history, anthropometric examination, physical examination, and biochemical testing at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), NAFLD Research Center (16, 17, 27, 30–33). All participants underwent phenotyping based on advanced MRI. NAFLD was assessed clinically and quantified by MRI-PDFF, an accurate, reproducible, and highly precise quantitative imaging-based biomarker for liver fat assessment. The presence of advanced fibrosis was diagnosed by MRE, an accurate, reproducible, and highly precise quantitative imaging-based biomarker for liver fibrosis assessment. MRI-PDFF and MRE were performed at the UCSD MR3T Research Laboratory as previously described (29, 34, 35). Informed consent was obtained from all patients. This study was approved by the UCSD Institutional Review Board (approval number 140084).

Probands (or NAFLD-cirrhosis cases) had documented evidence of NAFLD and cirrhosis either proven by biopsy or meeting imaging criteria. Definition of NAFLD was based on NAFLD practice guidelines.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria for the familial cirrhosis cohort.

Patients were included if they were adults at least 18 years old. Probands were required to have documented NAFLD based on AASLD guidelines (2) determined by hepatic steatosis of at least 5% assessed by MRI-PDFF (36) and cirrhosis determined by liver biopsy obtained for clinical care or quantified by MRE, with threshold reading greater than 3.63 kPa (29, 34, 35). First-degree relatives (sibling, child, or parent) with written informed consent who did not meet any exclusion criteria were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria included regular and excessive alcohol consumption within 2 years of recruitment (≥14 drinks per week for men or ≥7 drinks per week for women); use of hepatotoxic drugs or drugs known to cause hepatic steatosis; evidence of liver diseases other than NAFLD, including viral hepatitis (detected with positive serum hepatitis B surface antigen or hepatitis C viral RNA), Wilson’s disease, hemochromatosis, α1-antitrypsin deficiency, autoimmune hepatitis, and cholestatic or vascular liver disease; clinical or laboratory evidence of chronic illnesses associated with hepatic steatosis, including HIV infection, type 1 diabetes mellitus, celiac disease, cystic fibrosis, lipodystrophy, dysbetalipoproteinemia, and glycogen storage diseases; evidence of active substance abuse; significant systemic illnesses; contraindication(s) to MRI; pregnancy or trying to become pregnant; or any other condition that, in the investigator’s opinion, may affect the patient’s competence or compliance in completing the study.

Definition of NAFLD.

Participants were considered to have NAFLD if they had hepatic steatosis (MRI-PDFF ≥5%) and no secondary causes of hepatic steatosis due to factors including the use of steatogenic medications, other liver diseases, and significant alcohol intake (see exclusion criteria above for details).

Definition of cirrhosis and advanced fibrosis.

Participants were considered to have NAFLD-related cirrhosis if they had NAFLD according to the definition above and had biopsy-proven cirrhosis (histology fibrosis stage 4). We have previously validated that a liver stiffness cut point greater than 3.63 kPa on MRE provides an accuracy of 0.92 for the detection of advanced fibrosis, and it is the most accurate noninvasive test for the diagnosis of advanced fibrosis (29, 37–39). Advanced fibrosis among first-degree relatives was determined by either imaging evidence of nodularity and presence of intraabdominal varices or other imaging evidence of portal hypertension or liver stiffness assessment with MRE threshold ≥3.63 kPa (28, 29, 34).

Non-NAFLD control group.

The controls included 69 pairs (n = 138) of community-dwelling controls, either twin, sib-sib, or parent-offspring pairs: 69 individuals without any evidence of NAFLD randomly ascertained, paired with 69 of their first-degree relatives (51 twin pairs, 9 sib-sib pairs, and 9 parent-offspring pairs) (16, 17, 27). These twin, sib-sib, and parent-offspring pairs were prospectively recruited, and they resided in southern California. All participants underwent a standardized exhaustive clinical research visit including detailed medical history, physical examination, and testing to rule out other causes of chronic liver diseases (see inclusion and exclusion criteria for further details) and fasting laboratory tests at the UCSD NAFLD Research Center (16, 17, 27, 30–33), and then underwent an advanced magnetic resonance examination including MRI-PDFF and MRE at the UCSD MR3T Research Laboratory for the screening of NAFLD and advanced fibrosis (29, 34, 35). Research visits and MRI procedures for each twin pair were performed on the same day. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant, and the research protocol was approved by the UCSD Institutional Review Board (approval number 111282).

Twins without evidence of NAFLD (MRI-PDFF <5%) and advanced fibrosis (MRE <3.63 kPa) were considered as control, in a twin pair without NAFLD, non-NAFLD control twin and first-degree relative twin were randomly assigned to assess the risk of advanced fibrosis.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the controls.

Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria of the twin study are available in previously published references (16, 17, 27). Briefly, participants were included in the study if they were twins at least 18 years old who provided written informed consent. The zygosity of the majority of twin pairs as monozygotic or dizygotic had been confirmed through genetic testing before the participants enrolled in the study. Participants were excluded from the study if they met any of the following criteria: significant alcohol intake (>10 g/d in females or >20 g/d in males) for at least 3 consecutive months over the previous 12 months or inability to reliably ascertain the quantity of alcohol consumed; clinical or biochemical evidence of liver diseases other than NAFLD; chronic illnesses associated with hepatic steatosis; use of drugs known to cause hepatic steatosis; history of bariatric surgery; presence of systemic infectious illnesses; pregnancy or nursing at the time of the study; contraindications to MRI; or any other condition(s) that, based on the principal investigator’s opinion, may significantly affect the participant’s compliance, competence, or ability to complete the study.

Clinical assessments and laboratory tests.

All patients were carefully screened for other causes of liver diseases and secondary causes of hepatic steatosis. A detailed history was obtained from all patients. A physical examination, which included vital signs, height, weight, and anthropometric measurements, was performed by a trained clinical investigator. BMI was defined as the body weight (in kilograms) divided by height (in meters) squared. Alcohol consumption was documented in outside clinical visits and confirmed in the research clinic using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identifications Test and the Skinner questionnaire. A detailed history of medications was obtained, and no patient took medications known or suspected to cause steatosis or steatohepatitis. Other causes of liver disease were systematically ruled out using detailed history and laboratory data. Subjects underwent the following biochemical tests: aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, albumin, hemoglobin A1c, fasting glucose, insulin, prothrombin time, international normalized ratio, fasting lipid panel, platelet count, and ferritin.

Genotyping.

Whole-blood specimens collected during the research visit were used, and DNA was extracted. PNPLA3 genotyping was conducted, and its association in explaining the variance in hepatic steatosis and hepatic fibrosis was examined. The genotyping was performed by Human Longevity Inc.

MRI assessment.

MRI was performed at the UCSD MR3T Research Laboratory using the 3T research scanner (GE Signa EXCITE HDxt; GE Healthcare) with all participants in the supine position. MRI-PDFF was used to measure hepatic steatosis, and MRE was used to measure hepatic fibrosis. The details of the MRI protocol have been previously described in references (31, 40). The image analysts were blinded to all clinical and biochemical data, including the study group of the participants.

Justification for not using liver biopsy for assessment of liver fat and fibrosis in controls and first-degree relatives.

Liver biopsy was not used for liver fat and fibrosis assessment of controls and first-degree relatives, as they were asymptomatic with no suspected liver disease and therefore performing a liver biopsy would have been unethical. A noninvasive, accurate quantitative imaging method was used to estimate liver fat and fibrosis. We have previously shown that MRI-PDFF is a more precise marker of liver fat than liver biopsy (41), and previous studies suggest that MRE-stiffness is the most accurate currently available noninvasive quantitative biomarker of liver fibrosis (29, 34).

Rationale for using MRI-PDFF for hepatic steatosis quantification.

MRI-PDFF has been shown to be a highly precise, accurate, and reproducible noninvasive biomarker for the quantification of liver fat content (41, 42). It has been proven to correlate well with magnetic resonance spectroscopy (r2 = 0.99, P < 0.001) (30, 43) and histology-proven steatosis grade from contemporaneous liver biopsies (36, 40), and it is superior to ultrasound and CT for quantification of liver fat content (44).

Rationale for using MRE-stiffness for hepatic fibrosis quantification.

MRE has been shown to be a highly accurate, noninvasive biomarker to estimate hepatic fibrosis quantified by liver stiffness (29) and has been shown to be more accurate than clinical prediction rules (34) and ultrasound-based acoustic radiation force impulse imaging (39) for quantifying hepatic fibrosis with excellent diagnostic accuracy in differentiating between normal liver and mild fibrosis (stage 0–2) and between nonadvanced fibrosis and advanced fibrosis (stage 3–4) (45, 46).

Primary outcome.

The primary outcome was the assessment of advanced fibrosis in first-degree relatives of probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis.

Statistics.

Patients’ demographic, laboratory, and imaging data were summarized with mean and SD for continuous variables and numbers and percentages for categorical variables. For patient characteristics, a Student’s 2-tailed unpaired t test was used to compare continuous variables, and a χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables.

The prevalence of advanced fibrosis in the general population was derived from the risk of advanced fibrosis in the control non-NAFLD cohort by analysis of 69 individuals without evidence of NAFLD or advanced fibrosis from the twin study cohort and determination of whether their first-degree relatives had advanced fibrosis. Logistic regression analyses, unadjusted as well as multivariable-adjusted for age, sex, Hispanic ethnicity, BMI, and diabetes, were conducted to assess for the OR of presence of advanced fibrosis with a 2-tailed P value of ≤0.05 as statistically significant.

Sensitivity analyses.

Sensitivity analyses were also conducted using published estimates of cirrhosis in the general population in the United States ranging from 0.15% in 1998 (20) to 0.27% in 2010 (19). These estimates were used to derive the OR.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute), and a P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Sample size estimation.

We estimated that the prevalence of advanced fibrosis in the first-degree relatives of probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis would be approximately 18% based on prior estimates and the prevalence of advanced fibrosis in controls would be 1% or less. The power analysis estimated that a sample size of 30 first-degree relatives of NAFLD-cirrhosis patients would provide an 84% chance of detecting a significant difference in the prevalence of advanced fibrosis in the first-degree relatives of controls compared with the first-degree relatives of probands with NAFLD-cirrhosis with a significant α of 0.05 (2-tailed). Therefore, we had adequate power to detect an association between presence of cirrhosis due to NAFLD in a first-degree relative and presence of advanced fibrosis.

Study approval.

The study was approved by the UCSD Institutional Review Board (approval numbers 111282 and 140084). Written informed consent was obtained from each individual prior to his or her participation in the study.

Author contributions

RL designed the research study. RL, NS, MM, YK, IV, KM, JH, AH, BA, JS, LR, and DAB recruited the patients. SB, SC, MPG, and LR participated in the patients’ visit. SB, SC, MPG, MAI, CC, MS, and JC collected the data. CBS performed the imaging analysis. RB and CHC performed the statistical analysis. RL, CC, and MS performed the analysis and interpretation of data, drafted the manuscript. All coauthors revised the manuscript and approved the final submission.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

RL is supported in part by grants K23-DK090303 and R01-DK106419-01 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) National Institute of Heath. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the NIH under Award P42ES010337. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. CC is supported by grants from the Société Francophone du Diabète, the Philippe Foundation, and the Monahan Foundation.

Footnotes

Role of funding source: The funding sources had no role in the design of the conducted study.

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Reference information:J Clin Invest. 2017;127(7):2697–2704.https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI93465.

Contributor Information

Cyrielle Caussy, Email: ccaussy@ucsd.edu.

Meera Soni, Email: meerasoni6@gmail.com.

Jeffrey Cui, Email: cuijusc@gmail.com.

Ricki Bettencourt, Email: rbettencourt@ucsd.edu.

Nicholas Schork, Email: nschork@ucsd.edu.

Chi-Hua Chen, Email: chc101@ucsd.edu.

Shirin Bassirian, Email: sbassirian@ucsd.edu.

Sandra Cepin, Email: scepin11@gmail.com.

Michel Mendler, Email: mmendler@ucsd.edu.

Yuko Kono, Email: ykono@ucsd.edu.

Irine Vodkin, Email: ivodkin@ucsd.edu.

Kristin Mekeel, Email: kmekeel@ucsd.edu.

Alan Hemming, Email: ahemming@ucsd.edu.

Barbara Andrews, Email: bgandrews@ucsd.edu.

Joanie Salotti, Email: jsalotti@ucsd.edu.

Lisa Richards, Email: lrichards@ucsd.edu.

David A. Brenner, Email: dbrenner@ucsd.edu.

Rohit Loomba, Email: roloomba@ucsd.edu.

References

- 1.Loomba R, Sanyal AJ. The global NAFLD epidemic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10(11):686–690. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalasani N, et al. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Gastroenterological Association. Hepatology. 2012;55(6):2005–2023. doi: 10.1002/hep.25762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angulo P, et al. Liver fibrosis, but no other histologic features, is associated with long-term outcomes of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(2):389–97.e10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ekstedt M, et al. Fibrosis stage is the strongest predictor for disease-specific mortality in NAFLD after up to 33 years of follow-up. Hepatology. 2015;61(5):1547–1554. doi: 10.1002/hep.27368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loomba R, Chalasani N. The hierarchical model of NAFLD: prognostic significance of histologic features in NASH. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(2):278–281. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunt EM, Tiniakos DG. Histopathology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(42):5286–5296. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i42.5286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Udell JA, et al. Does this patient with liver disease have cirrhosis? JAMA. 2012;307(8):832–842. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charlton MR, Burns JM, Pedersen RA, Watt KD, Heimbach JK, Dierkhising RA. Frequency and outcomes of liver transplantation for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(4):1249–1253. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong RJ, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the second leading etiology of liver disease among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(3):547–555. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vernon G, Baranova A, Younossi ZM. Systematic review: the epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(3):274–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdelmalek MF, Liu C, Shuster J, Nelson DR, Asal NR. Familial aggregation of insulin resistance in first-degree relatives of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(9):1162–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Willner IR, Waters B, Patil SR, Reuben A, Morelli J, Riely CA. Ninety patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: insulin resistance, familial tendency, and severity of disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(10):2957–2961. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Struben VM, Hespenheide EE, Caldwell SH. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and cryptogenic cirrhosis within kindreds. Am J Med. 2000;108(1):9–13. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)00315-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loomba R, et al. Association between diabetes, family history of diabetes, and risk of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and fibrosis. Hepatology. 2012;56(3):943–951. doi: 10.1002/hep.25772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwimmer JB, et al. Heritability of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(5):1585–1592. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cui J, et al. Shared genetic effects between hepatic steatosis fibrosis: a prospective twin study. Hepatology. 2016;64(5):1547–1558. doi: 10.1002/hep.28674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loomba R, et al. Heritability of hepatic fibrosis and steatosis based on a prospective twin study. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(7):1784–1793. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chalasani N, et al. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guideline by the American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, and American College of Gastroenterology. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(7):1592–1609. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scaglione S, et al. The epidemiology of cirrhosis in the United States: a population-based study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(8):690–696. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schuppan D, Afdhal NH. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet. 2008;371(9615):838–851. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60383-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yki-Järvinen H. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease as a cause and a consequence of metabolic syndrome. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(11):901–910. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Romeo S, et al. Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40(12):1461–1465. doi: 10.1038/ng.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sookoian S, Pirola CJ. Meta-analysis of the influence of I148M variant of patatin-like phospholipase domain containing 3 gene (PNPLA3) on the susceptibility and histological severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2011;53(6):1883–1894. doi: 10.1002/hep.24283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rotman Y, Koh C, Zmuda JM, Kleiner DE, Liang TJ, NASH CRN The association of genetic variability in patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 (PNPLA3) with histological severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;52(3):894–903. doi: 10.1002/hep.23759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu YL, et al. TM6SF2 rs58542926 influences hepatic fibrosis progression in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4309. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chalasani N, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants associated with histologic features of nonalcoholic Fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(5):1567–1576. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zarrinpar A, Gupta S, Maurya MR, Subramaniam S, Loomba R. Serum microRNAs explain discordance of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in monozygotic and dizygotic twins: a prospective study. Gut. 2016;65(9):1546–1554. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar V, Shah AS, Singh D, Loomba PS, Singh H, Jagetia A. Ventriculoperitoneal shunt tube infection and changing pattern of antibiotic sensitivity in neurosurgery practice: Alarming trends. Neurol India. 2016;64(4):671–676. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.185408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loomba R, et al. Magnetic resonance elastography predicts advanced fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a prospective study. Hepatology. 2014;60(6):1920–1928. doi: 10.1002/hep.27362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le TA, et al. Effect of colesevelam on liver fat quantified by magnetic resonance in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a randomized controlled trial. Hepatology. 2012;56(3):922–932. doi: 10.1002/hep.25731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel NS, Peterson MR, Brenner DA, Heba E, Sirlin C, Loomba R. Association between novel MRI-estimated pancreatic fat and liver histology-determined steatosis and fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37(6):630–639. doi: 10.1111/apt.12237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neuschwander-Tetri BA, et al. Farnesoid X nuclear receptor ligand obeticholic acid for non-cirrhotic, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (FLINT): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9972):956–965. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61933-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tyagi A, et al. Intra- and inter-examination repeatability of magnetic resonance spectroscopy, magnitude-based MRI, and complex-based MRI for estimation of hepatic proton density fat fraction in overweight and obese children and adults. Abdom Imaging. 2015;40(8):3070–3077. doi: 10.1007/s00261-015-0542-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cui J, et al. Comparative diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance elastography vs. eight clinical prediction rules for non-invasive diagnosis of advanced fibrosis in biopsy-proven non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a prospective study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41(12):1271–1280. doi: 10.1111/apt.13196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loomba R, et al. Novel 3D magnetic resonance elastography for the noninvasive diagnosis of advanced fibrosis in NAFLD: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(7):986–994. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang A, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: MR imaging of liver proton density fat fraction to assess hepatic steatosis. Radiology. 2013;267(2):422–431. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dulai PS, Sirlin CB, Loomba R. MRI and MRE for non-invasive quantitative assessment of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in NAFLD and NASH: Clinical trials to clinical practice. J Hepatol. 2016;65(5):1006–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park CC, et al. Magnetic resonance elastography vs transient elastography in detection of fibrosis and noninvasive measurement of steatosis in patients with biopsy-proven nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(3):598–607.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cui J, et al. Magnetic resonance elastography is superior to acoustic radiation force impulse for the diagnosis of fibrosis in patients with biopsy-proven nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a prospective study. Hepatology. 2016;63(2):453–461. doi: 10.1002/hep.28337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Permutt Z, et al. Correlation between liver histology and novel magnetic resonance imaging in adult patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease — MRI accurately quantifies hepatic steatosis in NAFLD. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36(1):22–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05121.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noureddin M, et al. Utility of magnetic resonance imaging versus histology for quantifying changes in liver fat in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease trials. Hepatology. 2013;58(6):1930–1940. doi: 10.1002/hep.26455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reeder SB. Emerging quantitative magnetic resonance imaging biomarkers of hepatic steatosis. Hepatology. 2013;58(6):1877–1880. doi: 10.1002/hep.26543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Loomba R, et al. Ezetimibe for the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: assessment by novel magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance elastography in a randomized trial (MOZART trial) Hepatology. 2015;61(4):1239–1250. doi: 10.1002/hep.27647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reeder SB, Cruite I, Hamilton G, Sirlin CB. Quantitative assessment of liver fat with magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;34(4):729–749. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim D, Kim WR, Talwalkar JA, Kim HJ, Ehman RL. Advanced fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: noninvasive assessment with MR elastography. Radiology. 2013;268(2):411–419. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13121193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yin M, Glaser KJ, Talwalkar JA, Chen J, Manduca A, Ehman RL. Hepatic MR elastography: clinical performance in a series of 1377 consecutive examinations. Radiology. 2016;278(1):114–124. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015142141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.