Abstract

Bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) is a globally-distributed agent responsible for numerous clinical syndromes that lead to major economic losses. Two species, BVDV-1 and BVDV-2, discriminated on the basis of genetic and antigenic differences, are classified in the genus Pestivirus within the Flaviviridae family and distributed on all of the continents. BVDV-1 can be segregated into at least twenty-one subgenotypes (1a–1u), while four subgenotypes have been described for BVDV-2 (2a–2d). With respect to published sequences, the number of virus isolates described for BVDV-1 (88.2%) is considerably higher than for BVDV-2 (11.8%). The most frequently-reported BVDV-1 subgenotype are 1b, followed by 1a and 1c. The highest number of various BVDV subgenotypes has been documented in European countries, indicating greater genetic diversity of the virus on this continent. Current segregation of BVDV field isolates and the designation of subgenotypes are not harmonized. While the species BVDV-1 and BVDV-2 can be clearly differentiated independently from the portion of the genome being compared, analysis of different genomic regions can result in inconsistent assignment of some BVDV isolates to defined subgenotypes. To avoid non-conformities the authors recommend the development of a harmonized system for subdivision of BVDV isolates into defined subgenotypes.

Keywords: bovine viral diarrhea virus, epidemiology, global distribution, genetic diversity, subgenotyping

1. Introduction

Bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) is an important pathogen of cattle with a global distribution and causes major economic losses [1]. The two species BVDV-1 and BVDV-2 are members of the Pestivirus genus within the family Flaviviridae. Currently, the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) recognizes four approved Pestivirus species: BVDV-1, BVDV-2, Classical swine fever virus (CSFV), and Border disease virus (BDV) [2]. Moreover, a growing number of additional tentative Pestivirus species from various domestic and wildlife animal species has been described: (i) “Giraffe” virus, comprising an isolate obtained from a giraffe in Kenya, that caused mucosal disease-like symptoms, as well as one bovine isolate [3,4]; (ii) “Pronghorn” virus, isolated from a blind pronghorn antelope in the USA [5]; (iii) “Bungowannah” virus, that was isolated from pigs in Australia [6]; and (iv) atypical “HoBi-like” pestiviruses detected in the serum and other samples from bovine and buffalo [7,8,9]. Recently, additional putative new pestivirus species have been described, including Aydin-like viruses isolated from sheep and goats in Turkey [10], atypical porcine pestivirus causing congenital tremor in piglets [11,12], a pestivirus from a bat [13], and a pestivirus from rats [14]. In contrast to the approval and classification of Pestivirus species, subdivision of BVDV-1 and BVDV-2 into genetic groups is not an issue of the ICTV, but widely used in studies characterizing BVDV isolates.

Although pestiviruses were initially designated according to their host of origin, infections with BVDV have been detected in diverse domestic and wildlife animal species, including cattle, sheep, goat, pig, deer, buffalo, bison, and alpaca [15,16,17]. In addition to its respiratory, gastroenteric and reproductive clinical consequences, intrauterine infection of the fetus with BVDV can result in the birth of immunotolerant, persistently infected (PI) animals. These PI animals shed large amounts of virus during their life and are the main source of virus transmission to susceptible animals. Thus, identification and elimination of PI animals, together with the implementation of biosecurity measures, are crucial for control and prevention of the disease. Vaccination can represent an accompanying tool to prevent BVDV, but without removing PI animals it does not enable the elimination of the virus in a susceptible population. The genetic variations described for BVDV-1 and BVDV-2 may be implicated in disease control as diagnostics and vaccines that work well against homologous strains can be less efficacious for genetically-distinct viruses [18,19,20,21].

2. Genomic Organization

The genome of BVDV consists of a positive-stranded RNA molecule approximately 12.3 kb in length [22]. For most cytopathogenic BVDV strains considerably larger genomes have been described [23]. The single open reading frame (ORF) of the BVDV genome is flanked by untranslated regions (UTRs). The ORF encodes one large polyprotein, which is processed by cellular and viral proteases into four structural, and eight nonstructural, proteins ([24] and references therein). These mature proteins are Npro, C, Erns, E1, E2, p7, NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B. The first protein in the polyprotein, Npro, is a nonstructural viral autoprotease producing its own C-terminus. The nucleocapsid protein C and the three envelope glycoproteins Erns, E1, and E2 represent the structural proteins of BVDV. E2 is a highly-variable, immunologically-dominant glycoprotein in pestiviruses and the main target of neutralizing antibodies. The remaining mature proteins are nonstructural. The 5′UTR is a highly-conserved part of the viral genome and comprises an internal ribosome entry site essentially implicated in the translation of the viral polyprotein. The characteristics and functions of the individual pestivirus proteins, properties of the 5′ and 3′UTR, as well as molecular aspects of viral replication and cytopathogenicity of BVDV have been recently reviewed [23,24].

3. Mechanisms of Genetic Changes in BVDV Genomes

Genetic changes in pestivirus genomes result from three different processes: (1) accumulation of point mutations resulting from the error-prone nature of the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase; (2) non-homologous RNA recombination; and (3) homologous RNA recombination. Assuming that the mutation rate of pestiviruses is similar to those reported for other RNA viruses, it can be roughly estimated that one point mutation is introduced into the pestivirus genome per replication cycle [25,26]. For BVDV-1, different evolutionary rates have been published. Analysis of 5′UTR sequences of BVDV revealed a mean evolutionary rate of 9.3 × 10−3 substitutions/site/year for the investigated sequences [27]. Moreover, evolutionary rates of 5.9 × 10−4 and 1.26 × 10−3 substitutions/site/year have been reported for the 5′UTR and E1–E2 regions, respectively [28]. In addition, non-homologous RNA recombination can lead to the generation of cytopathogenic (cp) BVDV variants and a large variety of different genomic alterations have been described for cp pestiviruses ([23] and references therein). The emergence of cp BVDV in persistently-infected animals is crucial for the induction of fatal mucosal disease. Accordingly, RNA recombination, the emergence of cp BVDV, and pathogenesis of lethal mucosal disease are closely-linked processes [23]. Furthermore, homologous RNA recombination in pestivirus populations including BVDV-1 and BVDV-2 has been described [29,30,31]. Analysis of 125 complete pestivirus sequences provided evidence that the genomes of two BVDV-1, one BVDV-2, and four CSFV strains evolved from homologous recombination [30]. Depending on the genomic region used for phylogenetic analysis, the two recombinant BVDV-1 strains, ILLNC and 3156, are classified as either BVDV-1a or BVDV-1b, while the genome of the BVDV-2 strain JZ05-1 resulted from a recombination event between BVDV-2a and BVDV-2b. A recent in silico study on the evolution of BVDV identified five recombinants among 61 available complete BVDV-1 genomic sequences and confirmed that recombination in BVDV is not rare and can occur among viruses belonging to the same subgenotype or between different subgenotypes [31]. In addition, RNA recombination can occur even between the two species BVDV-1 and BVDV-2 [32]. The existence of recombinant pestiviruses represents a challenge for phylogenetic analysis and classification of virus isolates. In this context, it has been concluded that genotyping of pestivirus isolates should not be based on the analysis of a single genomic fragment [30]. While non-homologous RNA recombination is the major driving force for the generation of various cp virus variants, the existence of a growing number of BVDV subgenotypes is the result of point mutations accumulating over time, also known as genetic drift. In addition, homologous recombination contributes to the genetic diversification of BVDV. The genetic changes can hamper diagnosis of BVDV and may cause failure of protection provided by the established BVDV vaccines [33,34].

4. BVDV Variability

Variations among BVDV strains can be evaluated by different methods, including monoclonal antibody reactions, cross-neutralization tests, and a comparison of nucleotide sequences. Phylogenetic analyses of partial and complete genomic sequences provide more detailed information than studies based on reactions with antibodies and allow the rapid detection and discrimination of BVDV-1 and BVDV-2 subgenotypes, as well as the identification of novel subgenotypes. More than two decades ago BVDV isolates were segregated into BVDV-1 and BVDV-2 based on phylogenetic analysis of partial sequences [35,36]. Subsequent studies showed the existence of a growing number of BVDV-1 and BVDV-2 subgenotypes which are described in detail below. Today, it is well known that pestiviruses are genetically highly heterogeneous, even within the individual subgenotypes.

Different genomic regions, i.e., 5′UTR [7,21,35,36,37,38,39], Npro [3,16,17,35,39,40], E2 [3,16,37,41,42,43,44], NS2-3 [45,46], and NS5B-3′UTR [45,47] have been used for genotyping and classification of BVDV and other pestiviruses. Partial 5′UTR sequences have been most frequently used for phylogenetic analyses and genotyping of BVDV isolates, followed by Npro and E2 coding sequences, and almost all subgenotypes described so far have been classified according to these genomic regions (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5). In general, sequence data obtained from one of these genomic regions allow for comparisons with other virus strains only when sequence data of the same genomic region are available. Analyses of complete Npro and E2 coding sequences provide high confidence levels for the allocation of BVDV isolates into established and newly-identified subgenotypes. While the analysis of short partial 5′UTR sequences usually allows correct allocation of virus isolates to the established pestivirus species (e.g., BVDV-1) and, in many cases, also to defined subgenotypes, some of the observed BVDV-1 subgenotypes are supported by only low statistical values; consequently, several publications have indicated limitations of inferring BVDV phylogenies using the 5′UTR alone [17,28,30,46]. The main disadvantages of the 5′UTR with regard to its use for phylogenetic analyses are the restricted sequence length and lack of diversity. Consequently, the lack of information does not allow to clearly infer relationships within the major clades, and some branches and BVDV-1 subgenotypes are poorly supported by statistical values. The limited resolution and statistical support observed for phylogenetic analyses of 5′UTR sequences can be significantly improved by analyses of longer sequences and, therefore, it has been recommended to use, e.g., the complete Npro and E2 coding regions, or even the complete polyprotein coding region, for inferring phylogenies and genotyping of pestivirus isolates [17,28].

Table 1.

Distribution of Bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) subgenotypes in the Americas.

| Country | Genomic Region | Year of Isolation | BVDV-1 | BVDV-2 | Reference | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | s | t | u | ? | a | b | c | d | ? | ||||

| Argentina | 5′UTR, Npro, E2 | 1984–2010 | 23 | 36 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | (I) |

| Brazil | 5′UTR, Npro, E2 | 1994–2016 | 54 | 20 | 4 | 24 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | 2 | 50 | - | - | 3 | (II) |

| Peru and Chile | 5′UTR | 1993–2004 | 3 | 29 | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 5 | (III) |

| USA | 5′UTR, Npro, E2 | 1971–2015 | 184 | 652 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | 129 | 4 | - | - | 125 | (IV) |

| Canada | 5′UTR | 1990–1993 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | - | - | - | - | (V) |

| Uruguay | 5′UTR, Npro | 2014 | 12 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | (VI) |

| Total number | 277 | 738 | 6 | 24 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 139 | 59 | 1 | 1 | 137 | ||||||||||||||||||

Table 2.

Distribution of BVDV subgenotypes in Australia.

| Country | Genomic Region | Year of Isolation | BVDV-1 | BVDV-2 | Reference | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | s | t | u | a | b | c | d | ||||

| Australia | 5′UTR, Npro | 1971–2005 | 13 | 1 | 425 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | - | - | - | (I) |

| Total number | 13 | 1 | 425 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 3.

Distribution of BVDV subgenotypes in Africa.

| Country | Genomic Region | Year of Isolation | BVDV-1 | BVDV-2 | Reference | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | s | t | u | ? | a | b | c | d | ? | ||||

| Egypt | 5′UTR, Npro | 1994–2004 | - | 4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (I) |

| Tunisia | 5′UTR, Npro | 2001–2002 | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | - | - | - | - | (II) |

| South Africa | 5′UTR | 1990–2009 | 31 | 13 | 20 | 20 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 20 | - | - | - | - | - | (III) |

| Total number | 31 | 19 | 20 | 20 | 1 | 20 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 4.

Distribution of BVDV subgenotypes in Asia.

| Country | Genomic Region | Year of Isolation | BVDV-1 | BVDV-2 | Reference | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | s | t | u | ? | a | b | c | d | ? | ||||

| China | 5′UTR, Npro, E2 | 2005–2013 | 15 | 113 | 17 | 13 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 116 | - | 5 | 9 | 14 | - | - | - | 22 | 10 | 2 | 1 | - | - | 12 | (I) |

| India | 5′UTR, Npro, Erns-E1, E2, NS5B | 2000–2010 | - | 23 | 6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | 1 | - | - | - | (II) |

| Philippine | E2 | - | - | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (III) |

| Japan | 5′UTR, Npro | 1975–2006 | 216 | 558 | 226 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | - | - | 1 | 2 | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | 315 | - | - | - | 2 | (IV) |

| Korea | 5′UTR | 2005–2015 | 21 | 6 | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 18 | - | - | - | 1 | (V) |

| Mongolia | 5′UTR | 2014 | 4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | - | - | - | - | (VI) |

| Total number | 256 | 703 | 251 | 13 | 4 | 117 | 3 | 7 | 9 | 14 | 22 | 12 | 342 | 2 | 15 | |||||||||||||||

?: genotyping was not performed. References (I): [80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99]; (II): [47,100,101,102,103,104]; (III): [49]; (IV): [37,49,105,106,107,108,109]; (V): [110,111,112]; (VI): [113]. In [49], [83], [85] and [89] the year of virus isolation was not displayed in the study.

Table 5.

Distribution of BVDV subgenotypes in Europe.

| Country | Genomic Region | Year of Isolation | BVDV-1 | BVDV-2 | Reference | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | s | t | u | ? | a | b | c | d | ? | ||||

| Austria | 5′UTR, Npro | 1997–2006 | 4 | 52 | - | 33 | 6 | 142 | 7 | 154 | - | - | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 3 | (I) |

| Belgium | E2 | 1991–2002 | 1 | 19 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | 6 | - | - | - | 7 | (II) |

| Croatia | 5′UTR, Npro | 2007–2011 | - | 11 | - | - | - | 7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (III) |

| Czech Republic | 5′UTR, Npro | 2004–2007 | - | 16 | - | 16 | 2 | 7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (IV) |

| Denmark | 5′UTR, E2 | 1962–2012 | - | 16 | - | 32 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (V) |

| Finland | 5′UTR, Npro | 1994–2004 | - | - | - | 5 | - | 1 | - | - | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (VI) |

| France | 5′UTR, Npro | 1993–2005 | 3 | 15 | - | 3 | 46 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3▲ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | - | - | - | 3 | (VII) |

| Germany | 5′UTR, E2 | 1960–2014 | 1 | 31 | - | 24 | 24 | 65 | 3 | 17 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 11 | - | 16 | - | - | (VIII) |

| Hungary | 5′UTR, Npro | 1971–1998 | - | 2 | - | - | - | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (IX) |

| Ireland | 5′UTR | 1968–2014 | 428 | 19 | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 12 | - | - | (X) |

| Italy | 5′UTR, Npro | 1966–2016 | 16 | 193 | 2 | 27 | 141 | 55 | 8 | 20 | - | - | 3 | 1▲ | - | - | - | - | - | 2▲ | 1 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 10 | - | - | - | 5 | (XI) |

| Kosovo | 5′UTR | 2011 | - | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (XII) |

| Poland | 5′UTR, Npro | 2004–2011 | - | 31 | - | 24 | - | 8 | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | - | - | - | - | (XIII) |

| Portugal | 5′UTR | - | 6 | 19 | - | 3 | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 2 | - | - | - | (XIV) |

| Slovakia | 5′UTR, Npro | 1994–2004 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | (XV) |

| Slovenia | 5′UTR, Npro, C | 1997–2006 | - | 4 | - | 17 | 1 | 21 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (XVI) |

| Spain | 5′UTR, Npro | 1989–2015 | 3 | 162 | 2 | 9 | 8 | 2 | - | 2 | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | 6 | - | - | - | (XVII) |

| Sweden | 5′UTR, Npro | 2002–2004 | 7 | 28 | - | 77 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (XVIII) | |

| Switzerland | 5′UTR, Npro | 2008–2012 | - | 35 | - | - | 137 | 1 | - | 114 | - | - | 71 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | (XIX) |

| Turkey | 5′UTR, Npro, C, Erns, E2 | 1997–2012 | 7 | 11 | - | 7 | - | 20 | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | 34▲ | - | - | - | - | - | 3▲ | - | - | - | 7 | 5 | 1 | - | - | 14 | (XX) |

| United Kingdom | 5′UTR, Npro | 1966–2011 | 390 | 65 | - | 2 | 5 | 1 | - | - | 23 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | 7 | - | - | - | - | (XXI) |

| Total number | 866 | 732 | 4 | 281 | 376 | 334 | 21 | 309 | 24 | 3 | 79 | 39 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 24 | 50 | 9 | 28 | 32 | |||||||||

?: genotyping was not performed. ▲: Isolates from different clusters, but given the same name. References (I): [21,49,114,115,116]; (II): [41,49]; (III): [117]; (IV): [118]; (V): [119,120]; (VI): [52]; (VII): [21,49,121]; (VIII): [122,123,124,125,126]; (IX): [21]; (X): [127,128,129]; (XI): [21,49,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140]; (XII): [141]; (XIII): [142,143]; (XIV): [144]; (XV): [21,49,52]; (XVI): [145,146]; (XVII): [21,40,147,148,149,150,151,152]; (XVIII): [153]; (XIX): [9,154,155,156]; (XX): [157,158,159,160,161,162]; (XXI): [21,49,163,164,165,166]. In [9], the complete values were closest to the integral numbers, while the proportional values given in the related study are transformed into numerical data. In [125], certain number of the isolates segregated into subgenotypes 1b, 1d, 2a, and 2c are not indicated. In [144] and [166], the year of virus isolation was not displayed in the study. In [162] and [163] different typing regions were used. Samples are included into the unknown subgenotype category in case of ambiguous typing results reported for different regions.

Due to the lack of standardization and the use of different genomic regions for subgenotyping, inconsistent results have been reported with regard to allocation of some BVDV isolates into subgenotypes [104,162]. For example, the Japanese isolates “IS7NCP/97”, “IS8NCP/97”, and “IS14NCP/99” were placed in the BVDV-1a group according to their 5′UTR regions, but they were placed in the BVDV-1c group when the Npro and E2 coding regions were analyzed [38,45,47]. The same authors reported additional inconsistent results for two other virus isolates. Although Sakoda et al. [167] reported that the “190CP” and “190NCP” isolates belong to the BVDV-1a group according to their 5′UTR sequences, the same isolates were classified in the BVDV-1c group when the same genomic region was analyzed in another study [38,45]. Finally, these isolates were grouped as BVDV-1e when the Npro and E2 coding regions were studied [45,46]. Furthermore, Aguirre et al. [15] described BVDV isolates from llama and alpaca as BVDV-1j using 5′UTR sequences, but based on analysis of E2 coding sequences the same isolates were classified as BVDV-1e. The “So CP/75” isolate was first reported to represent a unique virus belonging to BVDV-1 [38,45] and later classified in the BVDV-1n group by the same authors with another isolate, “Shitara/02/06” [106]. However, their findings conflicted with the results of Xia et al. [46].

Another parameter, which may affect the results of phylogenetic analyses, is the use of various methods, i.e., neighbor-joining, maximum likelihood, or Bayesian methods [46]. While various methods resulted in consistent segregation of BVDV isolates into subgenotypes when the Npro and E2 coding regions were used, analysis of short nucleotide sequences from the 5′UTR can provide conflicting results for some BVDV isolates.

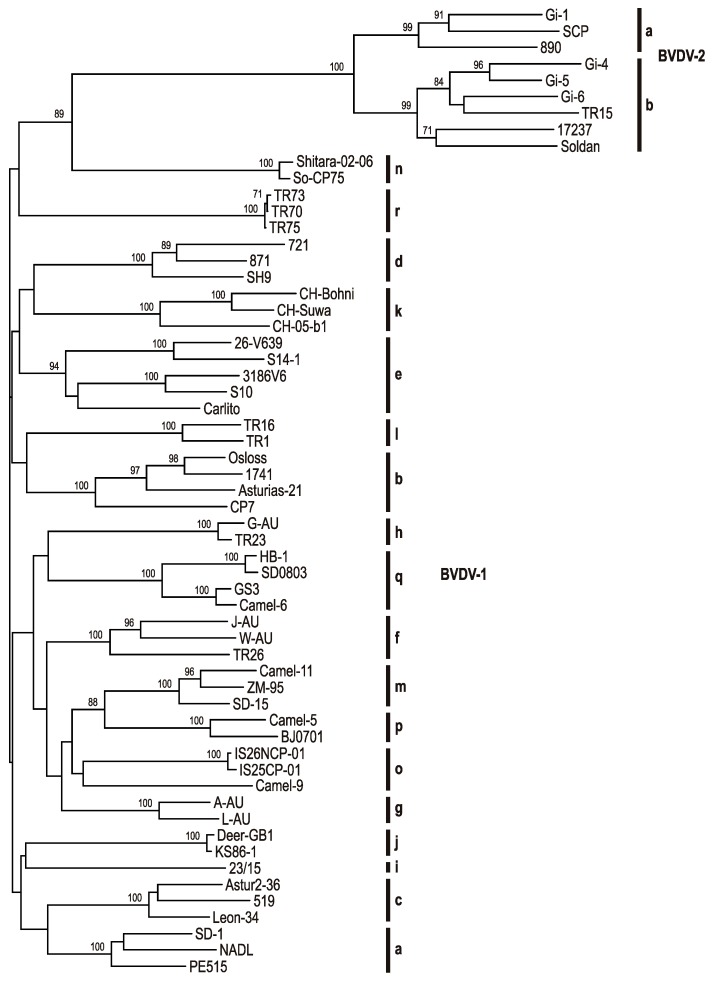

After the description of two BVDV-1 subgenotypes in the early 1990s [39], at least twenty-one BVDV-1 subgenotypes (BVDV-1a to -1u) and four BVDV-2 subgenotypes (BVDV-2a to -2d) have been described to date [21,81,49,90,106,121,136,160,161]. The phylogenetic tree based on the Npro coding sequences includes 18 BVDV-1 and two BVDV-2 subgenotypes; for the remaining BVDV-1 and BVDV-2 subgenotypes, complete Npro coding sequences are not available (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree based on full-length Npro encoding sequences of BVDV-1 and BVDV-2 isolates. Phylogenetic analysis of full-length Npro encoding sequences (504 nt) of fifty BVDV-1 and nine BVDV-2 isolates was performed using the neighbor joining method [168,169]. Genetic distances were calculated by the Kimura 2-parameter model [170]. Bootstrap values were calculated for 1000 replicates [171] and are indicated only for statistically significant values (≥70%). The vertical bars and letters indicate the subgenotypes of BVDV-1 (a–r) and BVDV-2 (a and b). GenBank accession numbers of sequence data used for phylogenetic analysis are: Gi-1:AF104030, SCP: U17149, 890:U18059, Gi-4:AF144468, Gi-5:AF144469, Gi-6:AF144470, TR15:EU163979, 17237:EU747875, Soldan:AY735495, Shitara-02-06:AB359930, So-CP75:AB359929, TR73:KF154777, TR70:KF154779, TR75:KF154778, 721:AF144463, 871:AF144462, SH9:AF144473, CH-Bohni:AY894997, Suwa:AY894998, CH-05-b1:EU180037, 26-V639:AF287281, S14-1:AY735490, 3186V6:AF287282, S10:AY735489, Carlito:KP313732, TR16:EU163964, TR1:EU163950, Osloss:M96687, 1741:AF321453, Asturias-21:AY182155, CP7:U63479, G-AU:AF287285, TR23:EU163971, HB-1:KC695812, SD0803:JN400273, GS3:KC695811, 6:KC695810, J:AF287286, W:AF287290, TR26:EU163974, 11:KC207075, ZM-95:AF526381, SD-15:KR866116, 5:KC207071, BJ0701:GU120259, IS26NCP-01:AB359932, IS25CP-01:AB359931, 9:KC207073, A-AU:AF287283, L-AU:AF287287, Deer-GB1:U80902, KS86-1:AB078950, 23-15:AF287279, Astur2-36:AY182162, 519:AF144464, Leon-34:AY182160, SD-1:M96751, NADL:M31182, PE515:EU180034.

According to the literature, a few BVDV isolates could not be allocated into one of the known subgenotypes and, in rare cases, the same subgenotype name was used in different studies for the designation of various BVDV-1 subgenotypes [121,136,160,161]. Apparently, the main reason for this confusing situation is the lack of a harmonized system for segregation of BVDV strains into subgenotypes. Moreover, concurrent submission of articles from different research groups for publication may constitute another reason for duplications in the designation of subgenotypes.

Currently, at least twenty-one BVDV-1 subgenotypes are either commonly accepted or have been recently suggested. Due to the highly variable structure of pestivirus genomes, it is very likely that additional subgenotypes will be reported. After BVDV-1v to BVDV-1z, we suggest to use two letters or a combination of letters and numbers for the designation of novel subgenotypes. Such a consensus classification system will keep the traditional names used for the established BVDV-1 subgenotypes and will facilitate the segregation of BVDV isolates in the future.

5. Global Distribution of BVDV Subgenotypes

Epidemiological studies have shown that various BVDV subgenotypes predominate in different countries. The segregation of BVDV isolates into subgenotypes is shown in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 for the individual continents. Viruses from the established subgenotypes have been detected not only in cattle, but also in pigs and a wide range of ruminant hosts, including sheep, goat, yak, buffalo, llama, alpaca, camel, deer, and bongo [15,16,17,35,42,47,67,80,86,88,103,172].

As noted above, different genomic regions were used for genetic typing of BVDV isolates [3,7,16,17,21,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,100,119,145,160,161] and, hence, it is not possible to create a comprehensive table of BVDV-1 and BVDV-2 subgenotypes on the basis of one single genomic region. Overall, the time periods for sampling vary considerably among the individual studies (summarized in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5). Therefore, it was virtually impossible to monitor temporal changes concerning the presence of subgenotypes in various countries. According to the literature, some consecutive studies analyzed the same BVDV isolates and provided consistent results with regard to segregation into subgenotypes. In contrast, for a few other BVDV isolates conflicting results have been reported when different genomic regions were used for genotyping ([38,45,46,105,106], for details see Section 4). Therefore, BVDV isolates with ambiguous segregation to BVDV subgenotypes were excluded from the tables.

With regard to the available published data, 31.6% (2193:6939) of the corresponding BVDV isolates addressed in this study belong to BVDV-1b, while BVDV-1a comprises 20.8% (1443:6939) of the classified isolates, as well as the majority of BVDV vaccine strains. While this analysis of published sequences probably does not reflect the precise distribution of BVDV subgenotypes in individual countries and continents, the calculated percentages provided in the present study can serve as a rough estimate for the presence and frequency of various BVDV subgenotypes. The present collection of data confirms that BVDV-1b is the predominant subgenotype worldwide, followed by BVDV-1a and -1c (Table 6). Considering the individual continents, BVDV-1b is the predominant subgenotype in the Americas, Asia and Europe. In contrast, according to the published data, almost all (95.9%) of the field isolates from Australia have been classified as BVDV-1c (Table 2 and Table 6). Although the total number of analyzed virus isolates from Africa is rather low and not representative for the whole continent, the limited set of data suggests that at least in South Africa BVDV-1a has been detected more frequently than other subgenotypes. The limited number of characterized virus isolates from Africa can be considered as one reason for the lower number of BVDV subgenotypes reported for this continent.

Table 6.

Continental distribution of BVDV subgenotypes *.

| Country | Genomic Region | Year of Isolation | BVDV-1 | BVDV-2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | s | t | u | ? | a | b | c | d | ? | |||

| Americas | 5′UTR, Npro, E2 | 1971–2010 | 277 | 738 | 6 | 24 | 1 | - | - | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 7 | 139 | 59 | 1 | 1 | 137 |

| Australia | 5′UTR, Npro | 1971–2005 | 13 | 1 | 425 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | - | - | - | - |

| Africa | 5′UTR, Npro | 1994–2004 | 31 | 19 | 20 | 20 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 20 | 3 | - | - | - | - |

| Asia | 5′UTR, Npro, Erns-E1, E2, NS5B | 1975–2012 | 256 | 703 | 251 | 13 | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | - | - | 117 | 3 | 7 | 9 | 14 | - | - | 22 | 12 | 342 | 2 | - | - | 15 | |

| Europe | 5′UTR, Npro, C, Erns, E2 | 1962–2012 | 866 | 732 | 4 | 281 | 376 | 334 | 21 | 309 | 24 | 3 | 79 | 39 | - | - | - | - | - | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 24 | 50 | 9 | 28 | - | 32 |

| Total number/individual subgenotype | 1443 | 2193 | 706 | 338 | 377 | 334 | 21 | 309 | 26 | 8 | 79 | 39 | 117 | 3 | 7 | 9 | 14 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 24 | 63 | 538 | 70 | 29 | 1 | 184 | ||

| Total number/species | 6117 | 822 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

* In order to avoid duplications, isolates from some consecutive studies which evaluated the isolates without identification were not included in the tables. ?: genotyping was not performed.

The results of the studies summarized in Table 6 suggest that the worldwide distribution of BVDV-1 including a total of 6117 isolates (88.2%) is significantly broader than the distribution of BVDV-2 isolates, including 822 isolates. The extensive genetic diversity of BVDV reflected by the number of detected subgenotypes has been described for several European countries, as well as for China and Turkey. It can be speculated that this high genetic variability could be related, at least to some extent, to the animal importation policies of these countries [109,173]. In contrast to many European (Table 5) and Asian countries (Table 4), BVDV-1 variation is considerably less developed in the Americas, Australia, and Africa (Table 6). Interestingly, BVDV-1m, -1n, -1o, -1p, and -1q subgenotypes have been detected so far exclusively in Asia. Similarly, the subgenotypes BVDV -1f, -1g, -1h, -1k, -1l, -1r, 1s, and -1t have not been reported to occur in countries outside Europe.

Unfortunately, identical letter codes were used for the designation of different BVDV-1 subgenotypes that were detected and first described at close intervals. After BVDV-1l was used for a newly recognized group of BVDV-1 isolates from Turkey in 2008 [160], the same subgenotype name was used for another distinct group of virus isolates reported in the same year [121]. Additionally, a similar conflict concerns the recently added subgenotype BVDV-1r which was initially used for the description of a distinct group of BVDV-1 isolates from Turkey in 2014 [161], but later the same designation was used for a group of different BVDV-1 isolates from Italy that was first described in 2015 [136].

BVDV-2 was first identified in Canada and the United States and the high prevalence reported in the 1990s did not significantly change during the past twenty years. Analyses over the past two decades showed the presence of BVDV-2 in a number of European countries, including Germany, Belgium, France, the United Kingdom, Slovakia, and Austria [174]. Further studies revealed an even broader distribution of BVDV-2, including virus isolates from all inhabited continents. BVDV-2a is the most prevalent subgenotype of BVDV-2 on all continents. BVDV-2c has been detected only in Europe and the Americas. One single contaminating BVDV strain from Argentina was classified as BVDV-2d, but additional members of this suggested subgenotype have not been detected since it was reported in 1995 [49].

6. Conclusions

Phylogenetic analyses of BVDV isolates can provide useful insights into the genetic relatedness among these viruses, which are either endemically present in an area for a longer time period or have been recently introduced, e.g., by animal imports. Accordingly, studies on molecular epidemiology of BVDV can assist in tracing virus isolates circulating in individual countries and globally. To date at least twenty-five different BVDV-1 and BVDV-2 subgenotypes have been described. However, a standardized and commonly-accepted system for genetic typing of BVDV isolates has not been established so far. Developing internationally-harmonized rules for discrimination and designation of BVDV subgenotypes will help to reduce inconsistencies in molecular typing of BVDV. Detailed knowledge about the variability of BVDV also provides useful information for evaluating the success of disease control programs. Moreover, different levels of cross-protection between highly variable BVDV-1 and BVDV-2 subgenotypes might be implicated in the success of vaccination programs.

Acknowledgments

The studies leading to the expertise to prepare this article have been financially supported by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TUBITAK) (project No.: 109 0 762), Uludag University Research Fund (project No: OUAP (V)-2014/19), and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Council; project No.: BE 2333/1 and 2). This publication was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, Foundation within the funding programme Open Access Publishing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Houe H. Epidemiological features and economical importance of bovine virus diarrhea virus BVDV infections. Vet. Microbiol. 1999;64:89–107. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(98)00262-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simmonds P., Becher P., Bukh J., Gould E.A., Meyers G., Monath T., Muerhoff S., Pletnev A., Rico-Hesse R., Smith D.B., et al. ICTV Report Consortium 2017. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile, Flaviviridae. J. Gen Virol. 2017;98:2–3. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becher P., Avalos-Ramirez R., Orlich M., Cedillo-Rosales S., König M., Schweizer M., Stalder H., Schirrmeier H., Thiel H.J. Genetic and antigenic characterization of novel pestivirus genotypes, implications for classification. Virology. 2003;311:96–104. doi: 10.1016/S0042-6822(03)00192-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becher P., Fischer N., Grundhoff A., Stalder H., Schweizer M., Postel A. Complete genome sequence of bovine pestivirus strain PG-2, a second member of the tentative pestivirus species Giraffe. Genome Announc. 2014;3:e00376-14. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00376-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vilcek S., Ridpath J.F., Van Campen H., Cavender J.L., Warge J. Characterization of a novel pestivirus originating from a pronghorn antelope. Virus Res. 2005;108:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirkland P.D., Read A.J., Frost M.J., Finlaison D.S. Bungowannah virus a probable new species of pestivirus what have we found in the last 10 years? Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2015;16:60–63. doi: 10.1017/S1466252315000031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cortez A., Heinemann M.B., De Castro Am M.G., Soares R.M., Pinto A.M.V., Alfieri A.A., Flores E.F., Leite R.C., Richtzenhain L.J. Genetic characterization of Brazilian bovine viral diarrhea virus isolates by partial nucleotide sequencing of the 5′UTR region. Pesq. Vet. Brasil. 2006;26:211–216. doi: 10.1590/S0100-736X2006000400005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schirrmeier H., Strebelow G., Depner K., Hoffmann B., Beer M. Genetic and antigenic characterization of an atypical pestivirus isolate. A putative member of a novel pestivirus species. J. Gen. Virol. 2004;8512:3647–3652. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stalder H.P., Meier P.H., Pfaffen G., Wageck-Canal C., Rüfenacht J., Schaller P., Bachofen C., Marti S., Vogt H.R., Peterhans E. Genetic heterogeneity of pestiviruses of ruminants in Switzerland. Prev. Vet. Med. 2005;72:37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Postel A., Schmeiser S., Oguzoglu T.C., Indenbirken D., Alawi M., Fischer N., Grundhoff A., Becher P. Close relationship of ruminant pestiviruses and classical swine fever virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015;21:668–672. doi: 10.3201/eid2104.141441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hause B.M., Collin E.A., Peddireddi L., Yuan F., Chen Z., Hesse R.A., Gauger P.C., Clement T., Fang Y., Anderson G. Discovery of a novel putative atypical porcine pestivirus in pigs in the USA. J. Gen. Virol. 2015;9610:2994–2998. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Postel A., Hansmann F., Bächlein C., Fischer N., Alawi M., Grundhoff A., Derking S., Tenhündfeld J., Pfankuche V.M., Herder V., et al. Presence of atypical porcine pestivirus APPV genomes in newborn piglets correlates with congenital tremor. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:27735. doi: 10.1038/srep27735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu Z., Ren X., Yang L., Hu Y., Yang J., He G., Zhang J., Dong J., Sun L., Du J., et al. Virome analysis for identification of novel mammalian viruses in bat species from Chinese provinces. J. Virol. 2012;86:10999–11012. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01394-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Firth C., Firth C., Bhat M., Firth M.A., Williams S.H., Frye M.J., Simmonds P., Conte J.M., Ng J., Garcia J., et al. Detection of zoonotic pathogens and characterization of novel viruses carried by commensal Rattus norvegicus in New York City. MBio. 2014;5:e01933-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01933-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aguirre I.M., Fuentes R., Celedón M.O. Genotypic characterization of Chilean llama (Lama glama) and alpaca (Vicugna pacos) pestivirus isolates. Vet. Microbiol. 2014;168:312–317. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Becher P., Orlich M., Kosmidou A., König M., Baroth M., Thiel H.J. Genetic diversity of pestiviruses, Identification of novel groups and implications for classification. Virology. 1999;262:64–71. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Becher P., Orlich M., Shannon AD., Horner G., König M., Thiel H.J. Phylogenetic analysis of pestiviruses from domestic and wild ruminants. J. Gen. Virol. 1997;78:1357–1366. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-6-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bauermann F.V., Ridpath J.F., Weiblen R., Flores E.F. HoBi-like viruses an emerging group of pestiviruses. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2013;251:6–15. doi: 10.1177/1040638712473103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peletto S., Zuccon F., Pitti M., Gobbi E., Marco L.D., Caramelli M., Masoero L., Acutis P.L. Detection and phylogenetic analysis of an atypical pestivirus, strain IZSPLV_To. Res. Vet. Sci. 2012;921:147–150. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ridpath J.F. Practical significance of heterogeneity among BVDV strains, impact of biotype and genotype on U.S. control programs. Prev. Vet. Med. 2005;721–722:17–30. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vilcek S., Paton D.J., Durkovic B., Strojny L., Ibata G., Moussa A., Loitsch A., Rossmanith W., Vega S., Scicluna M.T., et al. Bovine viral diarrhoea virus genotype 1 can be separated into at least eleven genetic groups. Arc. Virol. 2001;146:99–115. doi: 10.1007/s007050170194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collett M.S., Larson R., Belzer S.K., Retzel E. Proteins encoded by bovine viral diarrhea virus, the genomic organization of a pestivirus. Virology. 1988;1651:200–208. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90673-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Becher P., Tautz N. RNA recombination in pestiviruses, cellular RNA sequences in viral genomes highlight the role of host factors for viral persistence and lethal disease. RNA Biol. 2011;8:216–224. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.2.14514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tautz N., Tews B.A., Meyers G. The molecular biology of pestiviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 2015;93:47–160. doi: 10.1016/bs.aivir.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Domingo E., Martínez-Salas E., Sobrino F., De La Torre J.C., Portela A., Ortín J., López Galindez C., Pérez Breña P., Villanueva N., et al. The quasispecies extremely heterogeneous nature of viral RNA genome populations, biological relevance. Gene. 1985;40:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Becher P., Orlich M., König M., Thiel H.J. Nonhomologous RNA recombination in bovine viral diarrhea virus, molecular characterization of a variety of subgenomic RNAs isolated during an outbreak of fatal mucosal disease. J. Virol. 1999;73:5646–5653. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5646-5653.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luzzago C., Ebranati E., Sassera D., Lo Presti A., Lauzi S., Gabanelli E., Ciccozzi M., Zehender G. Spatial and temporal reconstruction of bovine viral diarrhea virus genotype 1 dispersion in Italy. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2012;122:324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chernick A., Godson D.L., van der Meer F. Metadata beyond the sequence enables the phylodynamic inference of bovine viral diarrhea virus type 1a isolates from Western Canada. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2014;28:367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones L.R., Weber E.L. Homologous recombination in bovine pestiviruses phylogenetic and statistic evidence. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2004;4:335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weber M.N., Streck A.F., Silveira S., Mósena A.C., Silva M.S., Canal C.W. Homologous recombination in pestiviruses, identification of three putative novel events between different subtypes/genogroups. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2015;30:219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kovago C., Hornyak A., Kekesi V., Rusvai M. Demonstration of homologous recombination events in the evolution of bovine viral diarrhoea virus by in silico investigations. Acta Vet. Hung. 2016;643:401–414. doi: 10.1556/004.2016.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ridpath J.F., Bolin S.R. Delayed onset postvaccinal mucosal disease as a result of genetic recombination between genotype 1 and genotype 2 BVDV. Virology. 1995;212:259–262. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fulton R.W., Ridpath J.F., Confer A.W., Saliki J.T., Burge L.J., Payton M.E. Bovine viral diarrhoea virus antigenic diversity, impact on disease and vaccination programmes. Biologicals. 2003;312:89–95. doi: 10.1016/S1045-1056(03)00021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zimmer G.M., Wentink G.H., Bruschke C., Westenbrink F.J., Brinkhof J., Goey I. Failure of foetal protection after vaccination against an experimental infection with bovine viral diarrhea virus. Vet. Microbiol. 2002;894:255–265. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(02)00203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Becher P., König M., Paton D.J., Thiel H.J. Further characterization of border disease virus isolates, evidence for the presence of more than three species within the genus pestivirus. Virology. 1995;209:200–206. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ridpath J.F., Bolin S.R., Dubovi E.J. Segregation of bovine viral diarrhea virus into genotypes. Virology. 1994;205:66–74. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abe Y., Tamura T., Torii S., Wakamori S., Nagai M., Mitsuhashi K., Mine J., Fujimoto Y., Nagashima N., Yoshino F., et al. Genetic and antigenic characterization of bovine viral diarrhea viruses isolated from cattle in Hokkaido, Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2016;781:61–70. doi: 10.1292/jvms.15-0186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagai M., Ito T., Sugita S., Genno A., Takeuchi K., Ozawa T., Sakoda Y., Nishimori T., Takamura K., Akashi H. Genomic and serological diversity of bovine viral diarrhea virus in Japan. Arch. Virol. 2001;1464:685–696. doi: 10.1007/s007050170139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ridpath J.F., Fulton R.W., Kirkland P.D., Neil J.D. Prevalence and antigenic differences observed between bovine viral diarrhea virus subgenotypes isolated from cattle in Australia and feedlots in the southwestern United States. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2010;22:184–191. doi: 10.1177/104063871002200203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arias P., Orlich M., Prieto M., Cedillo Rosales S., Thiel H.J., Alvarez M., Becher P. Genetic heterogeneity of bovine viral diarrhoea viruses from Spain. Vet. Microbiol. 2003;96:327–336. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Couvreur B., Letellier C., Collard A., Quenon P., Dehan P., Hamers C., Pastoret P., Kerkhofs P. Genetic and antigenic variability in bovine viral diarrhea virus BVDV isolates from Belgium. Virus Res. 2002;85:17–28. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1702(02)00014-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mingala C.N., Konnai S., Tajima M., Onuma M., Ohashi K. Classification of new BVDV isolates from Philippine water buffalo using the viral E2 region. J. Basic Microb. 2009;49:495–500. doi: 10.1002/jobm.200800310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silveira S., Weber M.N., Mósena A.C., da Silva M.S., Streck A.F., Pescador C.A., Flores E.F., Weiblen R., Driemeier D., Ridpath J.F., et al. Genetic Diversity of Brazilian Bovine Pestiviruses Detected Between 1995 and 2014. Transbound Emerg. Dis. 2015;64:613–623. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tajima M., Dubovi E.J. Genetic and clinical analyses of bovine viral diarrhea virus isolates from dairy operations in the United States of America. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2005;17:10–15. doi: 10.1177/104063870501700104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nagai M., Hayashi M., Sugita S., Sakoda Y., Mori M., Murakami T., Ozawa T., Yamada N., Akashi H. Phylogenetic analysis of bovine viral diarrhea viruses using five different genetic regions. Virus Res. 2004;992:103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xia H., Liu L., Wahlberg N., Baule C., Belák S. Molecular phylogenetic analysis of bovine viral diarrhoea virus, a Bayesian approach. Virus Res. 2007;130:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mishra N., Dubey R., Rajukumar K., Tosh C., Tiwari A., Pitale S.S., Pradhan H.K. Genetic and antigenic characterization of bovine viral diarrhea virus type 2 isolated from Indian goats (Capra hircus) Vet. Microbiol. 2007;124:340–347. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Craig M.I., König G.A., Benitez D.F., Draghi M.G. Molecular analyses detect natural coinfection of water buffaloes Bubalus bubalis with bovine viral diarrhea viruses BVDV in serologically negative animals. Rev. Argent Microbiol. 2015;472:148–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ram.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Giangaspero M., Harasawa R., Weber L., Belloli A. Taxonomic and epidemiological aspect of the bovine viral diarrhoea virus 2 through the observation of the secondary structures in the 5′ genomic untranslated region. Vet. Ital. 2008;44:319–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones L.R., Zandomeni R., Weber E.L. Genetic typing of bovine viral diarrhea virus isolates from Argentina. Vet. Microbiol. 2001;814:367–375. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(01)00367-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pecora A., Malacari D.A., Ridpath J.F., Perez Aguirreburualde M.S., Combessies G., Odeón A.C., Romera S.A., Golemba M.D., Wigdorovitz A. First finding of genetic and antigenic diversity in 1b-BVDV isolates from Argentina. Res. Vet. Sci. 2014;961:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vilcek S., Durkovic B., Kolesárová M., Greiser-Wilke I., Paton D. Genetic diversity of international bovine viral diarrhoea virus BVDV isolates, identification of a new BVDV-1 genetic group. Vet. Res. 2004;35:609–615. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2004036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bianchi M.V., Konradt G., de Souza S.O., Bassuino D.M., Silveira S., Mósena A.C., Canal C.W., Pavarini S.P., Driemeier D. Natural Outbreak of BVDV-1d-Induced Mucosal Disease Lacking Intestinal Lesions. Vet. Pathol. 2016;542:242–248. doi: 10.1177/0300985816666610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Flores E.F., Ridpath J.F., Weiblen R., Vogel F.S., Gil L.H. Phylogenetic analysis of Brazilian bovine viral diarrhea virus type 2 BVDV-2 isolates, evidence for a subgenotype with in BVDV-2. Virus Res. 2002;87:51–60. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1702(02)00080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lunardi M., Headley S.A., Lisbôa J.A., Amude A.M., Alfieri A.A. Outbreak of acute bovine viral diarrhea in Brazilian beef cattle, clinicopathological findings and molecular characterization of a wild-type BVDV strain subtype 1b. Res. Vet. Sci. 2008;853:599–604. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mósena A.C., Weber M.N., Cibulski S.P., Silveira S., Silva M.S., Mayer F.Q., Canal C.W. Genomic characterization of a bovine viral diarrhea virus subtype 1i in Brazil. Arch. Virol. 2017;1624:1119–1123. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-3199-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Otonel R.A., Alfieri A.F., Dezen S., Lunardi M., Headley S.A., Alfieri A.A. The diversity of BVDV subgenotypes in a vaccinated dairy cattle herd in Brazil. Trop. Anim. Health. Prod. 2014;461:87–92. doi: 10.1007/s11250-013-0451-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weber M.N., Silveira S., Machado G., Groff F.H., Mósena A.C., Budaszewski R.F., Dupont P.M., Corbellini L.G., Canal C.W. High frequency of bovine viral diarrhea virus type 2 in Southern Brazil. Virus Res. 2014;191:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pizarro Lucero J., Celedón M.O., Aguilera M., De Calisto A. Molecular characterization of pestiviruses isolated from bovines in Chile. Vet. Microbiol. 2006;115:208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ståhl K., Benito A., Felmer R., Zuñiga J., Reinhardt G., Rivera H., Baule C., Moreno-López J. Genetic diversity of bovine viral diarrhoea virus BVDV from Peru and Chile. Pesq. Vet. Brasil. 2009;29:41–44. doi: 10.1590/S0100-736X2009000100006. (In Portuguese) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ahn C.B., Walz P.H., Kennedy G.A., Kapil S. Biotype Genotype and Clinical presentation associated with bovine viral diarrhea virus BVDV isolates from cattle. Int. J. Appl. Res. Vet. Med. 2005;34:319–325. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Campen H.V., Ridpath J., Williams E., Cavender J., Edwards J., Smith S., Sawyer H. Isolation of bovine viral diarrhea virus from a free-ranging mule deer in Wyoming. J. Wildlife Dis. 2001;372:306–311. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-37.2.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Darweesh M.F., Rajput M.K.S., Braun L.J., Ridpath J.F., Neill J.D., Chase C.C.L. Characterization of the cytopathic BVDV strains isolated from 13 mucosal disease cases arising in a cattle herd. Virus Res. 2015;195:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Evermann J.F., Ridpath J.F. Clinical and epidemiologic observations of bovine viral diarrhea virus in the northwestern United States. Vet. Microbiol. 2002;89:129–139. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(02)00178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fulton R.W., Ridpath J.F., Ore S., Confer A.W., Saliki J.T., Burge L.J., Payton M.E. Bovine viral diarrhoea virus BVDV subgenotypes in diagnostic laboratory accessions, distribution of BVDV1a, 1b, and 2a subgenotypes. Vet. Microbiol. 2005;111:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fulton R.W., d’Offay J.M., Landis C., Miles D.G., Smith R.A., Saliki J.T., Ridpath J.F., Confer A.W., Neill J.D., Eberle R., et al. Detection and characterization of viruses as field and vaccine strains in feedlot cattle with bovine respiratory disease. Vaccine. 2016;3430:3478–3492. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim S.G., Anderson R.R., Yu J.Z., Zylich N.C., Kinde H., Carman S., Bedenice D., Dubovi E.J. Genotyping and phylogenetic analysis of bovine viral diarrhea virus isolates from BVDV infected alpacas in North America. Vet. Microbiol. 2009;136:209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pogranichniy R.M., Schnur M.E., Raizman E.A., Murphy D.A., Negron M., Thacker H.L. Isolation and Genetic Analysis of Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus from Infected Cattle in Indiana. Vet. Med. Int. 2011;2011:925910. doi: 10.4061/2011/925910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Workman A.M., Harhay G.P., Heaton M.P., Grotelueschen D.M., Sjeklocha D., Smith T.P. Full-length coding sequences for 12 bovine viral diarrhea virus isolates from persistently infected cattle in a feedyard in Kansas. Genome Announc. 2015;3:e00487-15. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00487-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yan L., Zhang S., Pace L., Wilson F., Wan H., Zhang M. Combination of reverse transcription real-time polymerase chain reaction and antigen capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of animals persistently infected with Bovine viral diarrhea virus. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2011;231:16–25. doi: 10.1177/104063871102300103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Deregt D., Tessaro S.V., Baxi M.K., Berezowski J., Ellis J.A., Wu J.T., Gilbert S.A. Isolation of bovine viral diarrhoea viruses from bison. Vet. Rec. 2005;15715:448–450. doi: 10.1136/vr.157.15.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maya L., Puentes R., Reolón E., Acuña P., Riet F., Rivero R., Cristina J., Colina R. Molecular diversity of bovine viral diarrhea virus in Uruguay. Arch. Virol. 2016;1613:529–535. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2688-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mahony T.J., McCarthy F.M., Gravel J.L., Corney B., Young P.L., Vilcek S. Genetic analysis of bovine viral diarrhoea viruses from Australia. Vet. Microbiol. 2005;106:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2004.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Abdel-Latif A.O., Goyal S.M., Chander Y., Abdel-Moneim A.S., Tamam S.M., Madbouly H.M. Isolation and molecular characterisation of a pestivirus from goats in Egypt. Acta Vet. Hung. 2013;612:270–280. doi: 10.1556/AVet.2013.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Soltan M.A., Wilkes R.P., Elsheery M.N., Elhaig M.M., Riley M.C., Kennedy M.A. Circulation of bovine viral diarrhea virus-1 BVDV-1 in dairy cattle and buffalo farms in Ismailia Province, Egypt. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2015;9:1331–1337. doi: 10.3855/jidc.7259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thabti F., Bakkali Kassimi L., M’zah A., Ben Romdane S., Russo P., Ben Said M.S., Hammami S., Pepin M. First detection and genetic characterization of bovine viral diarrhoea viruses BVDV types 1 and 2 in Tunisia. Rev. Med. Vet-Toulouse. 2005;156:419–422. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Baule C., van Vuuren M., Lowings J.P., Belák S. Genetic heterogeneity of bovine viral diarrhoea viruses isolated in Southern Africa. Virus Res. 1997;522:205–220. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1702(97)00119-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kabongo N., Baule C., Van Vuuren M. Molecular analysis of bovine viral diarrhoea virus isolates from South Africa. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 2003;704:273–279. doi: 10.4102/ojvr.v70i4.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ularamu H.G., Sibeko K.P., Bosman A.B., Venter E.H., van Vuuren M. Genetic characterization of bovine viral diarrhoea BVD viruses, confirmation of the presence of BVD genotype 2 in Africa. Arch. Virol. 2013;1581:155–163. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1478-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Deng Y., Sun C.Q., Cao S.J., Lin T., Yuan S.S., Zhang H.B., Zhai S.L., Huang L., Shan T.L., Zheng H., et al. High prevalence of bovine viral diarrhea virus 1 in Chinese swine herds. Vet. Microbiol. 2012;159:490–493. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Deng M., Ji S., Fei W., Raza S., He C., Chen Y., Chen H., Guo A. Prevalence Study and Genetic Typing of Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus BVDV in Four Bovine Species in China. PLoS ONE. 2015;104:e0121718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gao S., Luo J., Du J., Lang Y., Cong G., Shao J., Lin T., Zhao F., Belák S., Liu L., et al. Serological and molecular evidence for natural infection of Bactrian camels with multiple subgenotypes of bovine viral diarrhea virus in Western China. Vet. Microbiol. 2013;163:172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gao S., Du J., Shao J., Lang Y., Lin T., Cong G., Zhao F., Belák S., Liu L., Chang H., et al. Genome analysis reveals a novel genetically divergent subgenotype of bovine viral diarrhea virus in China. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2014;21:489–491. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gao S., Du J., Tian Z., Xing S., Luo J., Liu G., Chang H., Yin H. Genome Sequence of a Subgenotype 1a Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus in China. Genome Announc. 2016;4:e01280-16. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01280-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gong X., Cao X., Zheng F., Chen Q., Zhou J., Yin H., Liu L., Cai X. Identification and characterization of a novel subgenotype of bovine viral diarrhea virus isolated from dairy cattle in Northwestern China. Virus Genes. 2013;462:375–376. doi: 10.1007/s11262-012-0861-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gong X., Liu L., Zheng F., Chen Q., Li Z., Cao X., Yin H., Zhou J., Cai X. Molecular investigation of bovine viral diarrhea virus infection in yaks (Bos gruniens) from Qinghai, China. Virol. J. 2014;11:29. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-11-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mao L., Li W., Yang L., Wang J., Cheng S., Wei Y., Wang Q., Zhang W., Hao F., Ding Y., et al. Primary surveys on molecular epidemiology of bovine viral diarrhea virus 1 infecting goats in Jiangsu province, China. BMC Vet. Res. 2016;12:181. doi: 10.1186/s12917-016-0820-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tao J., Wang Y., Wang J., Wang J.Y., Zhu G.Q. Identification and genetic characterization of new bovine viral diarrhea virus genotype 2 strains in pigs isolated in China. Virus Genes. 2013;46:81–87. doi: 10.1007/s11262-012-0837-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Xie Z., Fan Q., Xie Z., Liu J., Pang Y., Deng X., Xie L., Luo S., Khan M.I. Complete genome sequence of a bovine viral diarrhea virus strain isolated in southern China. Genome Announc. 2014;2:512–514. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00512-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Xue F., Zhu Y.M., Li J., Zhu L.C., Ren X.G., Feng J.K., Shi H.F., Gao Y.R. Genotyping of bovine viral diarrhea viruses from cattle in China between 2005 and 2008. Vet. Microbiol. 2010;143:379–383. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang W., Shi X., Chen C., Wu H. Genetic characterization of a noncytopathic bovine viral diarrhea virus 2b isolated from cattle in China. Virus Genes. 2014;49:339–341. doi: 10.1007/s11262-014-1067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wang W., Shi X., Tong Q., Wu Y., Xia M.Q., Ji Y., Xue W., Wu H. A bovine viral diarrhea virus type 1a strain in China, isolation, identification, and experimental infection in calves. Virol. J. 2014;11:8. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-11-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Weng X.G., Song Q.J., Wu Q., Liu M.C., Wang M.L., Wang J.F. Genetic characterization of bovine viral diarrhea virus strains in Beijing, China and innate immune responses of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in persistently infected dairy cattle. J. Vet. Sci. 2015;16:491–500. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2015.16.4.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhang J.J., Ma C., Li X.Z., Liu Y.X., Huang K., Cao J. Genetic diversity of bovine viral diarrhoea virus in Beijing region, China from 2009 to 2010. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2013;74:4934–4939. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang S., Tan B., Ding Y., Wang F., Guo L., Wen Y., Cheng S., Wu H. Complete genome sequence and pathogenesis of bovine viral diarrhea virus JL-1 isolate from cattle in China. Virol. J. 2014;11:67. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-11-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zhong F., Li N., Huang X., Guo Y., Chen H., Wang X., Shi C., Zhang X. Genetic typing and epidemiologic observation of bovine viral diarrhea virus in Western China. Virus Genes. 2011;42:204–207. doi: 10.1007/s11262-010-0558-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhu L.Q., Lin Y.Q., Ding X.Y., Ren M., Tao J., Wang J.Y., Zhang G.P., Zhu G.Q. Genomic sequencing and characterization of a Chinese isolate of Bovine viral diarrhea virus 2. Acta Virol. 2009;53:197–202. doi: 10.4149/av_2009_03_197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhu L.Q., Ren M., Lin Y.Q., Ding X.Y., Zhang G.P., Zhao X., Zhu G.Q. Identification of a bovine viral diarrhea virus 2 isolated from cattle in China. Acta Virol. 2009;53:131–134. doi: 10.4149/av_2009_02_131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhu L., Lu H., Cao Y., Gai X., Guo C., Liu Y., Liu J., Wang X. Molecular Characterization of a Novel Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus Isolate SD-15. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0165044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Behera S.P., Mishra N., Vilcek S., Rajukumar K., Nema R.K., Prakash A., Kalaiyarasu S., Dubey S.C. Genetic and antigenic characterization of bovine viral diarrhoea virus type 2 isolated from cattle in India. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2011;34:189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mishra N., Pattnaik B., Vilcek S., Patil SS., Jain P., Swamy N., Bhatia S., Pradhan H.K. Genetic typing of bovine viral diarrhoea virus isolates from India. Vet. Microbiol. 2004;10:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mishra N., Pitale S.S., Rajukumar K., Prakash A., Behera S.P., Nema R.K., Dubey S.C. Genetic variety of bovine viral diarrhea virus 1 strains isolated from sheep and goats in India. Acta Virol. 2012;56:209–215. doi: 10.4149/av_2012_03_209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mishra N., Rajukumar K., Vilcek S., Tiwari A., Satav J.S., Dubey S.C. Molecular characterization of bovine viral diarrhea virus type 2 isolate originating from a native Indian sheep (Ovies aries) Vet. Microbiol. 2008;130:88–98. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mishra N., Vilcek S., Rajukumar K., Dubey R., Tiwari A., Galav V., Pradhan H.K. Identification of bovine viral diarrhea virus type 1 in yaks (Bos poephagus grunniens) in the Himalayan region. Res. Vet. Sci. 2008;84:507–510. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2007.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Matsuno K., Sakoda Y., Kameyama K., Tamai K., Ito A., Kida H. Genetic and pathobiological characterization of bovine viral diarrhea viruses recently isolated from cattle in Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2007;68:515–520. doi: 10.1292/jvms.69.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nagai M., Hayashi M., Itou M., Fukutomi T., Akashi H., Kida H., Sakoda Y. Identification of new genetic subtypes of bovine viral diarrhea virus genotype 1 isolated in Japan. Virus Genes. 2008;36:135–139. doi: 10.1007/s11262-007-0190-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sato A., Tateishi K., Shinohara M., Naoi Y., Shiokawa M., Aoki H., Ohmori K., Mizutani T., Shirai J., Nagai M. Complete Genome Sequencing of Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus 1, Subgenotypes 1n and 1o. Genome Announc. 2016;4:e01744-15. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01744-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tajima M. Bovine viral diarrhea virus 1 is classified into different subgenotypes depending on the analyzed region within the viral genome. Vet. Microbiol. 2004;99:131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yamamoto T., Kozasa T., Aoki H., Sekiguchi H., Morino S., Nakamura S. Genomic analyses of bovine viral diarrhea viruses isolated from cattle imported into Japan between 1991 and 2005. Vet. Microbiol. 2008;127:386–391. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Han Y.J., Chae J.B., Chae J.S., Yu D.H., Park J., Park B.K., Kim H.C., Yoo J.G., Choi K.S. Identification of bovine viral diarrhea virus infection in Saanen goats in the Republic of Korea. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2016;48:1079–1082. doi: 10.1007/s11250-016-1042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Oem J.K., Hyun B.H., Cha S.H., Lee K.K., Kim S.H., Kim H.R., Park C.K., Joo Y.S. Phylogenetic analysis and characterization of Korean bovine viral diarrhea viruses. Vet. Microbiol. 2009;139:356–360. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yang D.K., Kim B.H., Kweon C.H., Park J.K., Kim H.Y., So B.J., Kim I.J. Genetic typing of bovine viral diarrhea viruses BVDV circulating in Korea. J. Bacteriol. Virol. 2007;37:147–152. doi: 10.4167/jbv.2007.37.3.147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ochirkhuu N., Konnai S., Odbileg R., Odzaya B., Gansukh S., Murata S., Ohashi K. Molecular detection and characterization of bovine viral diarrhea virus in Mongolian cattle and yaks. Arch. Virol. 2016;161:2279–2283. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-2890-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hornberg A., Fernández S.R., Vogl C., Vilcek S., Matt M., Fink M., Köfer J., Schöpf K. Genetic diversity of pestivirus isolates in cattle from Western Austria. Vet. Microbiol. 2009;135:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Krametter-Froetscher R., Duenser M., Preyler B., Theiner A., Benetka V., Moestl K., Baumgartner W. Pestivirus infection in sheep and goats in West Austria. Vet. J. 2010;186:342–346. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Vilcek S., Greiser-Wilke I., Durkovic B., Obritzhauser W., Deutz A., Köfer J. Genetic diversity of recent bovine viral diarrhoea viruses from the southeast of Austria (Styria) Vet. Microbiol. 2003;91:285–291. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(02)00296-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Bedekovi T., Lojki I., Lemo N., Čač Ž., Cvetni Ž., Lojki M., Madi J. Genetic typing of Croatian bovine viral diarrhea virus isolates. Vet. Arch. 2012;82:449–462. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Robesova B., Kovarcik K., Vilcek S. Genotyping of bovine viral diarrhoea virus isolates from the Czech Republic. Vet. Med. 2009;54:393–398. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Nagy A., Fahnøe U., Rasmussen T.B., Uttenthal A. Studies on genetic diversity of bovine viral diarrhea viruses in Danish cattle herds. Virus Genes. 2014;48:376–380. doi: 10.1007/s11262-013-1020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Uttenthal Å., Stadejek T., Nylin B. Genetic diversity of bovine viral diarrhoea viruses BVDV in Denmark during a 10-year eradication period. Acta Path. Micro Im. 2005;113:536–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2005.apm_227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Jackova A., Novackova M., Pelletier C., Audeval C., Gueneau E., Haffar A., Petit E., Rehby L., Vilcek S. The extended genetic diversity of BVDV-1, Typing of BVDV isolates from France. Vet. Res. Commun. 2008;32:7–11. doi: 10.1007/s11259-007-9012-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Beer M., Wolf G., Kaaden O.R. Phylogenetic analysis of the 5′-untranslated region of German BVDV type II isolates. J. Vet. Med. B Infect. Dis. Vet. Public Health. 2002;49:43–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0450.2002.00536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Gethmann J., Homeier T., Holsteg M., Schirrmeier H., Saßerath M., Hoffmann B., Beer M., Conraths F.J. BVD-2 outbreak leads to high losses in cattle farms in Western Germany. Heliyon. 2015;21:e00019. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2015.e00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Jenckel M., Höper D., Schirrmeier H., Reimann I., Goller K.V., Hoffmann B., Beer M. Mixed triple, allied viruses in unique recent isolates of highly virulent type 2 bovine viral diarrhea virus detected by deep sequencing. J. Virol. 2014;88:6983–6992. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00620-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Schirrmeier H. Three years of mandatory BVDV control in Germany–lessons to be learned; Proceedings of the XXVIII World Buiatric Congress; Cairns, Australia. 27 July–1 August 2014; pp. 245–248. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Tajima M., Frey H.R., Yamato O., Maede Y., Moennig V., Scholz H., Greiser-Wilke I. Prevalence of genotypes 1 and 2 of bovine viral diarrhea virus in Lower Saxony, Germany. Virus Res. 2001;76:31–42. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1702(01)00244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Grahama D.A., Larena I.E.M.C., Brittaina D., O’reilly P.J. Genetic typing of ruminant pestivirus strains from Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. Res. Vet. Sci. 2001;71:127–134. doi: 10.1053/rvsc.2001.0499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Guelbenzu-Gonzalo M.P., Cooper L., Brown C., Leinster S., O’Neill R., Doyle L., Graham D.A. Genetic diversity of ruminant Pestivirus strains collected in Northern Ireland between 1999 and 2011 and the role of live ruminant imports. Ir. Vet. J. 2016;69:7. doi: 10.1186/s13620-016-0066-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.O’Brien E., Garvey M., Walsh C., Arkins S., Cullinane A. Genetic typing of bovine viral diarrhoea virus in cattle on Irish farms. Res. Vet. Sci. 2017;111:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2016.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Bazzucchi M., Bertolotti L., Giammarioli M., Casciari C., Rossi E., Rosati S., De Mia G.M. Complete Genome Sequence of a Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus Subgenotype 1h Strain Isolated in Italy. Genome Announc. 2017;5:e01697-16. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01697-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Cannella V., Giudice E., Ciulli S., Marco P.D., Purpari G., Cascone G., Annalisa G. Genotyping of bovine viral diarrhea viruses BVDV isolated from cattle in Sicily. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2012;21:1733–1738. doi: 10.1007/s00580-011-1358-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Cerutti F., Luzzago C., Lauzi S., Ebranati E., Caruso C., Masoero L., Moreno A., Acutis P.L., Zehender G., Peletto S. Phylogeography, phylodynamics and transmission chains of bovine viral diarrhea virus subtype 1f in Northern Italy. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2016;45:262–267. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ciulli S., Purpari G., Agnello S., Di Marco P., Di Bella S., Volpe E., Mira F., de Aguiar Saldanha Pinheiro A.C., Vullo S., Guercio A. Evidence for Tunisian-Like Pestiviruses Presence in Small Ruminants in Italy Since 2007. Transbound Emerg. Dis. 2016 doi: 10.1111/tbed.12498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Decaro N., Lucente M.S., Lanave G., Gargano P., Larocca V., Losurdo M., Ciambrone L., Marino P.A., Parisi A., Casalinuovo F., et al. Evidence for Circulation of Bovine Viral Diarrhoea Virus Type 2c in Ruminants in Southern Italy. Transbound Emerg. Dis. 2016 doi: 10.1111/tbed.12592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Falcone E., Cordioli P., Tarantino M., Muscillo M., Rosa G., Tollis M. Genetic Heterogeneity of Bovine Viral Diarrhoea Virus in Italy. Vet. Res. Commun. 2003;27:485–494. doi: 10.1023/A:1025793708771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Giammarioli M., Ceglie L., Rossi E., Bazzucchi M., Casciari C., Petrini S., De Mia G.M. Increased genetic diversity of BVDV-1, recent findings and implications thereof. Virus Genes. 2015;50:147–151. doi: 10.1007/s11262-014-1132-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Giammarioli M., Pellegrini C., Casciari C., Rossi E., Mia G.M. Genetic diversity of Bovine viral diarrhea virus 1, Italian isolates clustered in at least seven subgenotypes. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2008;20:783–788. doi: 10.1177/104063870802000611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Giangaspero M., Harasawa R., Zecconi A., Luzzago C. Genotypic characteristics of bovine viral diarrhea virus 2 strains isolated in northern Italy. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2001;63:1045–1049. doi: 10.1292/jvms.63.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Luzzago C., Bandi C., Bronzo V., Ruffo G., Zecconi A. Distribution pattern of bovine viral diarrhoea virus strains in intensive cattle herds in Italy. Vet. Microbiol. 2001;83:265–274. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(01)00429-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Luzzago C., Lauzi S., Ebranati E., Giammarioli M., Moreno A., Cannella V., Masoero L., Canelli E., Guercio A., Caruso C., et al. Extended Genetic Diversity of Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus and Frequency of Genotypes and Subtypes in Cattle in Italy between 1995 and 2013. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014;2014:147145. doi: 10.1155/2014/147145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Goga I., Berxholi K., Hulaj B., Sylejmani D., Yakobson B., Stram Y. Genotyping and phylogenetic analysis of bovine viral diarrhea virus BVDV isolates in Kosovo. Vet. Ital. 2014;50:69–72. doi: 10.12834/VetIt.1304.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Kuta A., Polak M.P., Larska M., Żmudziński J.F. Predominance of bovine viral diarrhea virus 1b and 1d subtypes during eight years of survey in Poland. Vet. Microbiol. 2013;166:639–644. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Polak M.P., Kuta A., Rybałtowski W., Rola J., Larska M., Zmudziński J.F. First report of bovine viral diarrhoea virus-2 infection in cattle in Poland. Vet. J. 2014;202:643–645. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Barros S.C., Ramos F., Paupério S., Thompson G., Fevereiro M. Phylogenetic analysis of Portuguese bovine viral diarrhoea virus. Virus Res. 2006;118:192–195. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Toplak I., Sandvib T., Barlič-Maganja D., Grom J., Paton D.J. Genetic typing of bovine viral diarrhoea virus, most Slovenian isolates are of genotypes 1d and 1f. Vet. Microbiol. 2004;99:175–185. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Toplak I., Kuhar U., Kušar D., Papić B., Koren S., Toplak N. Complete Genome Sequence of a Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus Subgenotype 1e Strain, SLO/2407/2006, Isolated in Slovenia. Genome Announc. 2016;17:e01310-16. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01310-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Aduriz G., Atxaerandio R., Cortabarria N. First detection of bovine viral diarrhoea virus type 2 in cattle in Spain. Vet. Rec. Open. 2015;2:e000110. doi: 10.1136/vetreco-2014-000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Diéguez F.J., Eiras C., Sanjuán M.L., Vilar M., Arnaiz I., Yus E. Variabilidad genética del virus de la diarrea vírica bovina BVDV en Galicia. Producción Animal. 2008;239:4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 149.Factor C., Yus E., Eiras C., Sanjuan M.L., Cerviño M., Arnaiz I., Diéguez F.J. Genetic diversity of bovine viral diarrhea viruses from the Galicia region of Spain. Vet. Rec. Open. 2016;3:e000196. doi: 10.1136/vetreco-2016-000196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Hurtado A., García-Pérez A.L., Aduriz G., Juste R.A. Genetic diversity of ruminant pestiviruses from Spain. Virus Res. 2003;92:67–73. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1702(02)00315-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Partida E.L., Fernández M., Gutiérrez J., Esnal A., Benavides J., Pérez V., de la Torre A., Álvarez M., Esperón F. Detection of Bovine Viral Diarrhoea Virus 2 as the Cause of Abortion Outbreaks on Commercial Sheep Flocks. Transbound Emerg. Dis. 2016;641 doi: 10.1111/tbed.12599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Rodríguez-Prieto V., Kukielka D., Rivera-Arroyo B., Martínez-López B., de las Heras A.I., Sánchez-Vizcaíno J.M., Vicente J. Evidence of shared bovine viral diarrhea infections between red deer and extensively raised cattle in south-central Spain. BMC Vet. Res. 2016;12:11. doi: 10.1186/s12917-015-0630-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Ståhl K., Kampa J., Baule C., Isaksson M., Moreno-Lopez J., Belak S., Alenius S., Lindberg A. Molecular epidemiology of bovine viral diarrhoea during the final phase of the Swedish BVD-eradication programme. Prev. Vet. Med. 2005;72:103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2005.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Bachofen C., Stalder H., Braun U., Hilbe M., Ehrensperger F., Peterhans E. Co-existence of genetically and antigenically diverse bovine viral diarrhoea viruses in an endemic situation. Vet. Microbiol. 2008;13:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Stalder H., Schweizer M., Bachofen C. Complete Genome Sequence of a Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus Subgenotype 1e Strain Isolated in Switzerland. Genome Announc. 2015;3:e00636-15. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00636-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]