Summary

Background

Carriage of Staphylococcus aureus is a risk for infections. Targeted decolonization reduces postoperative infections but depends on accurate screening.

Aim

To compare detection of S. aureus carriage in healthy individuals between anatomical sites and nurse- versus self-swabbing; also to determine whether a single nasal swab predicted carriage over four weeks.

Methods

Healthy individuals were recruited via general practices. After consent, nurses performed multi-site swabbing (nose, throat, and axilla). Participants performed nasal swabbing twice-weekly for four weeks. Swabs were returned by mail and cultured for S. aureus. All S. aureus isolates underwent spa typing. Persistent carriage in individuals returning more than three self-swabs was defined as culture of S. aureus from all or all but one self-swabs.

Findings

In all, 102 individuals underwent multi-site swabbing; S. aureus carriage was detected from at least one site from 40 individuals (39%). There was no difference between nose (29/102, 28%) and throat (28/102, 27%) isolation rates: the combination increased total detection rate by 10%. Ninety-nine patients returned any self-swab, and 96 returned more than three. Nasal carriage detection was not significantly different on nurse or self-swab [28/99 (74%) vs 26/99 (72%); χ2: P = 0.75]. Twenty-two out of 25 participants with first self-swab positive were persistent carriers and 69/71 with first self-swab negative were not, giving high positive predictive value (88%), and very high negative predictive value (97%).

Conclusion

Nasal swabs detected the majority of carriage; throat swabs increased detection by 10%. Self-taken nasal swabs were equivalent to nurse-taken swabs and predicted persistent nasal carriage over four weeks.

Keywords: Staphylococcus aureus, Carriage, Multi-site screening, spa typing

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is a widespread commensal organism, whose primary human reservoir is the nose.1 S. aureus nasal carriage (SANC) prevalence in adults is about 30% on cross-sectional studies.2 Carriage also occurs at other sites, and throat swabs are reported as more effective for detecting meticillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA).3, 4, 5

Population genomics suggest that SANC is usually founded as a single colonizing event, but mixed carriage can be demonstrated in a minority using relatively low-resolution methods such as spa typing.6, 7 Moreover, SANC exhibits complex dynamics within individuals, with acquisition and loss of S. aureus occurring.8 Classifications of carriage states differ widely. A longitudinal study of SANC in 571 adults over two years defined carriage loss as two or more negative swabs two months apart.8 One classification defines ‘persistent’ carriers as isolation of S. aureus from >80% of cultures, and another uses qualitative and quantitative cultures to identify as ‘truly persistent’ and ‘never’ carriers.9, 10

Identifying and understanding S. aureus carriage is important in clinical settings because S. aureus causes infections ranging from superficial boils to life-threatening septicaemia, pneumonia, and osteomyelitis, and SANC increases the risk of these infections.2, 11, 12, 13, 14 Infection prevention strategies such as decolonization successfully reduce the incidence of postoperative infection in carriers, and screening allows the targeting of these interventions and reduced antimicrobial use.15, 16 Screening with targeted decolonization has been integrated into some postoperative infection prevention guidelines, but the design of programmes for screening and targeted decolonization remains an unsolved challenge.17, 18

Both research studies and pre-admission screening to target preoperative decolonization require either extensive investigator or healthcare personnel time, or reliance on self-swabbing. There is growing evidence from large studies that self-swabbing is acceptable to study participants, but there is limited data on the accuracy of self-swabbing by patients.19, 20 One study compared investigator to participant swabs, but these study participants were nursing personnel, and may not have represented patients who are not healthcare professionals.21 Further, it is unclear how accurately samples taken weeks before admission predict carriage at admission.17

This study addressed these uncertainties by assessing S. aureus carriage in healthy individuals, sampling this cohort every three to four days over four weeks. Nasal swabs underwent culture for S. aureus and all isolates underwent spa typing. Our aims were: (i) to compare isolation rates from three different body sites; (ii) to compare the results of nurse and participant swabs; (iii) to consider the ability of single nasal swab to predict persistent carriage over the next four weeks; and (iv) to identify new acquisitions using spa typing. Collectively this study aimed to improve our understanding of what can be predicted about carriage by a single nasal swab.

Methods

Eligible participants were adults aged ≥16 years, who were invited when attending two general practices between October and December 2011 (Oxfordshire Ethics Committee B, reference 08/H0605/102). Written consent was obtained from all participants. The recruiting nurse took multi-site swabs from nose, axilla, and throat. Participants were trained to sample both anterior nares with a dry swab and given a leaflet demonstrating the technique. Packs with numbered swabs and return envelopes were provided and individuals took subsequent nose swabs themselves, returning them by mail to the John Radcliffe Hospital. Swabs were taken twice weekly for four weeks.

Swabs were returned in charcoal media within a week from sample collection and were stored at 4°C before processing (within four days). Swabs were incubated in 5% saline enrichment broth (Oxoid Ltd, Basingstoke, UK) overnight at 37°C before subculture on to SaSelect chromogenic agar (Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd, Watford, UK) for 24 h. Confirmation of S. aureus isolates was by DNase and Prolex Staph Xtra Latex kit (Pro-Lab Diagnostics, Wirral, UK). Meticillin resistance was tested on Columbia agar with 5.0% salt (Oxoid Ltd) with BBL™ Sensi-Disc™ 1 μg Oxacillin discs (BD, Oxford, UK). A mixture of isolates taken from a sweep of the culture plate was stored at –80°C in 15% glycerol. Extraction of crude DNA and spa typing of isolates was performed as previously described with chromatograms analysed using the software Ridom StaphType v2.0.3 (Ridom GmbH, Münster, Germany).22 Where mixed chromatograms were found, spa typing was repeated using 12 individual colonies.

Carriage was defined as a nose, throat, or axilla swab positive for growth of S. aureus. Persistent carriage was assessed in those returning more than three self-swabs and was defined as the presence of S. aureus in all nose self-swabs returned in the study period, or at most one nose self-swab negative. Nasal carriage loss was defined as ≥2 consecutive post-baseline nasal swabs negative after previous nasal carriage detection. A single negative nose swab was not considered carriage loss, due to the limited sensitivity of swabbing.

Data were analysed using R (3.2.0). Proportions were compared using χ2-test or Fisher’s exact test (depending upon cell size).

Results

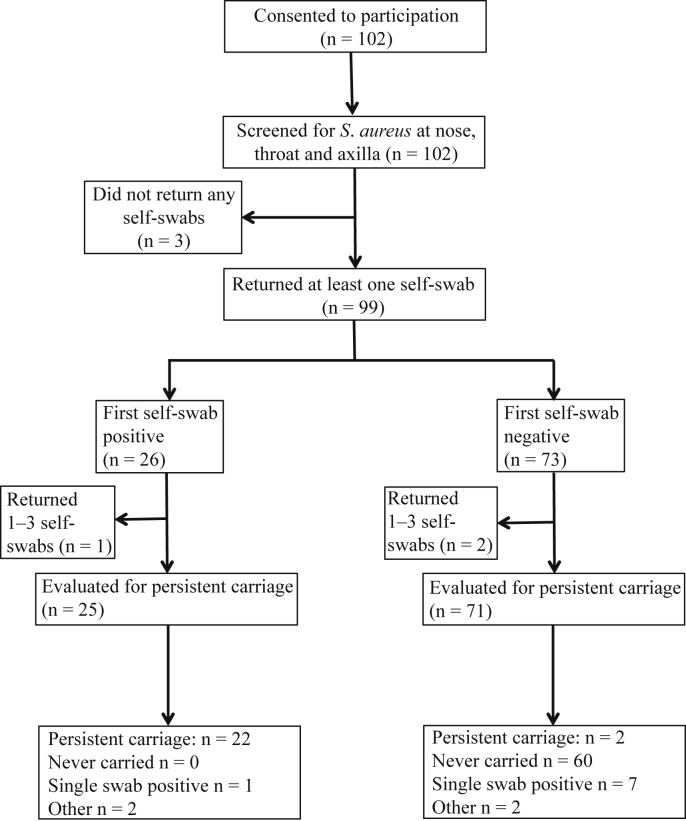

A total of 102 individuals [mean age: 60 years (SD: 15.2), 39% male] were recruited between October and December 2011. Of these, 99 returned at least one self-swab and 96 returned more than three self-swabs (Figure 1). The median time between nurse swab and arrival of first self-swab was six days.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patient participation from recruitment, through nurse swabbing, first self-swab, and repeated self-swabs. Numbers of patients included and excluded at each stage are shown, along with the patterns detected on multiple self-swabs.

Multi-site swabbing by study personnel

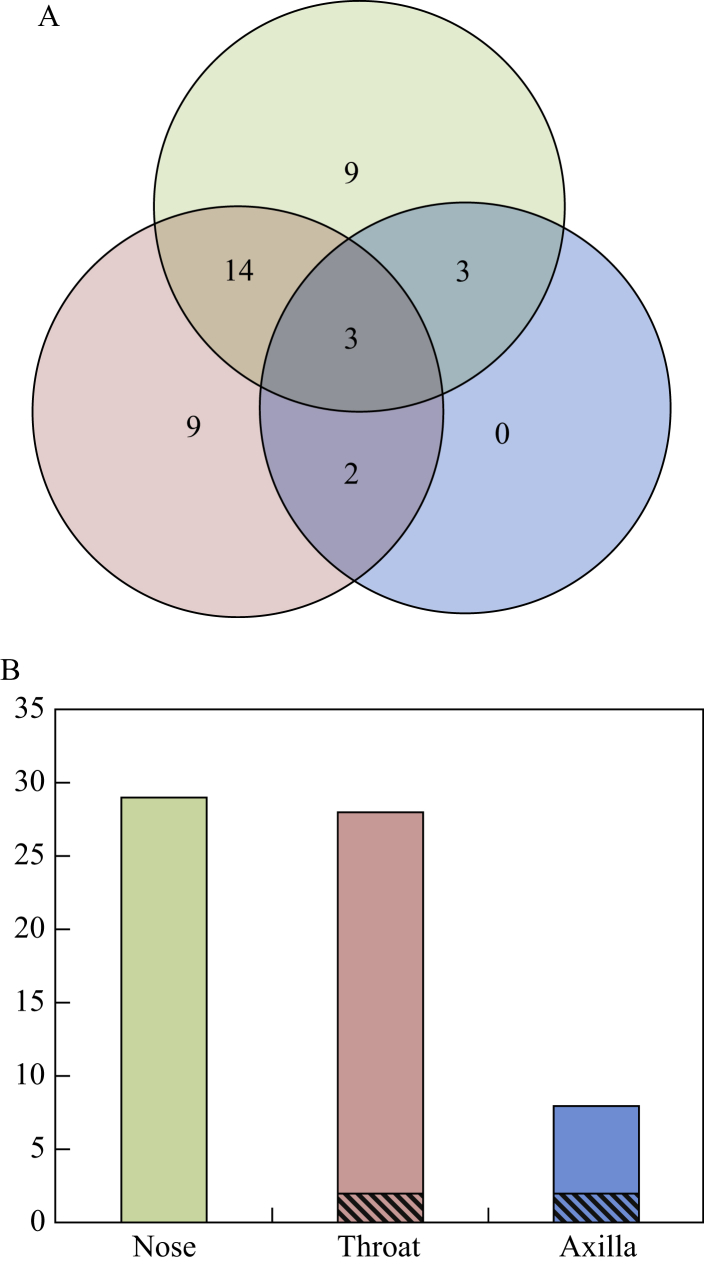

A total of 102 individuals underwent multi-site swabbing, and S. aureus carriage was detected from at least one site in 40 individuals, an overall carriage rate of 39%. There was no difference in the isolation rate between nose (29/102, 28%) and throat (28/102, 27%) (χ2: P = 0.88). Axilla swabs were positive in 8% (8/102), significantly lower than both nose (exact P = 0.0002) and throat (exact P = 0.0004). S. aureus was detected at multiple sites in 22 participants (22%) (Figure 2A). Whereas 18% of participants had only nose or throat carriage (9% each), there were no participants with carriage in the axilla only. All S. aureus isolates were meticillin susceptible.

Figure 2.

(A) A total of 102 patients underwent swabbing of three sites by a study nurse. Numbers in circles are the numbers of participants with S. aureus cultured from nose only (green), throat only (red) or axilla only (blue), and number of people with multiple S. aureus cultured from each combination of anatomical sites. (B) Number of patients with S. aureus cultured from a swab from each anatomical site with a single spa type (solid colours) or a mixture of spa types (hatched).

All isolates underwent spa typing (Supplementary Table I). Of 22 individuals with carriage at multiple sites, 15 (68%) had identical spa profiles at all sites, and seven had discordant spa profiles (Table I). Three participants (5057, 5076, 5082) had a mixture at one site, with a matching single spa type at another site. Three participants (5001, 5031, 5046) had different spa types at two sites, with no overlap between sites. Participant 5067 had two spa types, with a different profile at each site (a mixture of two spa types in axilla, with each of the spa types found as single spa in the nose and throat). Axillary swabbing detected more mixed spa type carriage (Figure 2B), with the axillary swab significantly more likely to be mixed than nasal (2/8 mixed vs 0/29 mixed; exact P = 0.04).

Table I.

spa types recovered in individuals with carriage at multiple sites and discordant spa profiles

| Participant | Nose | Throat | Axilla |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5001 | t748 | t9725 | NG |

| 5031 | NG | t156 | t748 |

| 5046 | NG | t085 | t008 |

| 5057 | t3978 | t3978/t688 | NG |

| 5067 | t722 | t954 | t722/t954 |

| 5076 | t385 | NG | t385/t9974 |

| 5082 | t2643 | t2643/t521 | NG |

NG, S. aureus not grown at this site.

Nose swabbing by participants

Ninety-nine returned at least one self-swab (Figure 1); for these 99, self-collected nasal swabs were compared with nurse-collected nasal and throat swabs. Nurse-administered nasal swabs were similar to the first self-administered swabs in terms of carriage rates [28/99 (28%) vs 26/99 (26%) respectively; χ2: P = 0.75]. Considering carriage on either swab as positive, sensitivity was similar for nurse-administered and self-swabs [28/31 (90%) versus 26/31 (84%), exact P = 0.71]. For those with nasal carriage found by both, spa types showed high concordance: 22/23 (96%) had identical spa typing results. One individual had a multiple spa types in the self-swab with only one of the two spa types detected on nurse nose swab. In contrast, whereas nurse-administered throat swabs showed similar sensitivity to self-collected nose swabs [both finding 26/33 (79%), exact P = 1], spa types were concordant in only 11/16 (69%), significantly less than that seen between nurse nose swab and self nose swab (exact P = 0.03). Two out of 16 (12%) individuals showed a mixture of spa types on nurse-collected throat swab not found on the self-swab, and 3/16 (19%) showed unrelated spa types on each.

Twice weekly nose swabbing over one month

In the 96 participants who returned more than three self-administered swabs, the first swab predicted persistent carriage over the next four weeks (Figure 1). Twenty-five had an initial positive swab, and, of these, 20 (80%) were positive on all swabs throughout the study period and two participants (5039 and 5086) had just one swab negative from a series of positive swabs. Of the remaining three: participant 5031 had only one swab positive, participant 5024 lost carriage at swab 5, and participant 5048 showed both carriage loss (swab 4) and gain (swab 6) (Figure 3, Supplementary Table I).

Figure 3.

Ninety-nine patients returned self-swabs from the nose over a four-week period. Four participants were found to have carriage on multiple swabs without meeting the definition of persistent carriage and two showed changing spa type. spa types recovered are plotted against swab number; related spa types are enclosed in a dotted-line box.

Of the 71 individuals evaluated for persistent carriage whose first swab was negative, 60 (85%) had negative swabs throughout the next four weeks. Of the remaining 11, seven participants (5032, 5035, 5036, 5054, 5062, 5093, 5100) had a single swab positive; two participants (5077, 5098) had only the first swab negative and were otherwise positive, meeting the definition for persistent carriage. Participant 5091 showed gain (swab 3) and loss (swab 5), and participant 5042 showed multiple gains (swab 3, swab 7) and loss (swab 4) (Figure 3, Supplementary Table I).

Twenty-two out of 25 participants with first swab positive were classified as persistent carriers over the next four weeks and 69/71 with first swab negative were not, giving a high positive predictive value (88%), and a very high negative predictive value (97%).

Twenty-eight participants returned more than three positive swabs; 24 were persistent carriers and four had multiple changes from positive to negative results with the same spa type on each positive swab (Supplementary Table I). Twenty-two of 24 persistent carriers showed a single spa type throughout the study, indicating stable spa type carriage. Two persistent carriers had variable spa typing profiles (Figure 3): participant 5083 carried a mixture of two related spa types (t360 and t803) on five swabs, with spa type t360 found alone on the other four swabs; participant 5067 had two unrelated spa types (t772 and t954) found on four swabs each with the spa profile switching five times and with a mixture of the two found on the penultimate swab. The carried spa type was stable during the study period for 26/28 (93%) individuals with S. aureus on multiple swabs; a small minority (2/28) displayed mixed and changing spa profiles.

Discussion

Nasal swabs had the highest rate of detecting S. aureus, and did not differ significantly from throat swabs in the estimated rate of carriage. Other studies have identified higher rates of throat carriage; this may vary according to the study population.4, 5 Our results are consistent with other studies in which throat swabs detected around 10% additional carriers.23 Whereas no single site detects all S. aureus carriage, studies demonstrating that S. aureus carriage is a risk for infection have focused on SANC.5, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 23 This study supports the use of nasal swabs to detect S. aureus carriage, finding that throat swabbing is additive but not superior for detecting carriage, and that the spa types isolated from throat and nose show limited concordance.

In this study, spa typing indicated that the axilla swab was more likely to be mixed, but the clinical significance of this is unclear. Although the use of an axilla swab did not increase the detection of carriage, the greater diversity of spa types identified from this anatomical site suggests that the inclusion of axillary sampling may help detect carriers of a specific strain in outbreak investigations.

Self-administered swabs after education performed similarly well to nurse-administered swabs, adding to the existing evidence that self-swabbing is acceptable, and further indicating that it is a sensitive tool for larger epidemiological studies of SANC.19, 21 Several such studies have used self-administered swabs for cross-sectional and cohort studies, and this study, though limited in sample size, demonstrates the accuracy of self-swabbing by patients who are not healthcare professionals.8, 19, 20

Previous studies of SANC have conducted swabbing at intervals of one or two months, the latter study demonstrating that carriage gain and loss are frequent events.8, 20 Sampling nasal carriage more frequently, we demonstrated that an initial swab was highly predictive of carriage over the following month, complementing a previous finding that two positive nasal cultures a week apart predicted persistent carriage over 12 weeks.10 Our data also show that spa types were stable over the short term in most individuals. Both participants with changing spa types showed a mixture on at least one sample. These results may reflect mixed colonization with varying results due either to sampling or fluctuating population size. Alternatively they may represent repeated acquisitions from a close contact. These findings support the use of screening at four- to eight-week intervals in epidemiological studies of SANC dynamics.

Identifying SANC has several important implications in healthcare. Screening for MRSA has been the focus of infection control policies in order both to halt transmission and to prevent invasive infection.16, 23 For the prevention of invasive infection, detection of meticillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) is also important, as MSSA is responsible for many serious infections.24 S. aureus infection is usually related to SANC, and evidence suggests that S. aureus undergoes genetic modification in the transition from carriage to invasion.13, 14, 25 Decolonization treatment can reduce infections originating from SANC: targeted decolonization reduces surgical site infection; non-targeted decolonization reduces all bacteraemias in an ICU setting, and in the following year outside the ICU.15, 26, 27 Outside of the ICU, non-targeted use of antibiotics is unlikely to be supported amid increasing recognition of the impact of antimicrobial resistance.18 Our study raises the possibility of patient self-swabbing for effective and resource-efficient pre-admission screening for SANC and targeted preoperative decolonization.

In conclusion, this study found that nose and throat nurse swabs identified similar overall rates of carriage, and that self-administered nasal swabs were a reliable method of identifying carriage and of predicting the likelihood of carriage over a four-week period.

Acknowledgements

We thank the study participants; also C. Gordon, D. Wilson, D. Mant, and R. Bowden for comments on study design.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2017.01.015.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding sources

This study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre, Oxford. B. Young is funded by a Wellcome Trust Research Training Fellowship (Grant 101611/Z/13/Z).

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Williams R.E. Healthy carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: its prevalence and importance. Bacteriol Rev. 1963;27:56–71. doi: 10.1128/br.27.1.56-71.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kluytmans J., van Belkum A., Verbrugh H. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology, underlying mechanisms, and associated risks. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:505–520. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.3.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dancer S.J., Noble W.C. Nasal, axillary, and perineal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus among women: identification of strains producing epidermolytic toxin. J Clin Pathol. 1991;44:681–684. doi: 10.1136/jcp.44.8.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mertz D., Frei R., Periat N. Exclusive Staphylococcus aureus throat carriage: at-risk populations. Archs Intern Med. 2009;169:172–178. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bignardi G.E., Lowes S. MRSA screening: throat swabs are better than nose swabs. J Hosp Infect. 2009;71:373–374. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golubchik T., Batty E.M., Miller R.R. Within-host evolution of Staphylococcus aureus during asymptomatic carriage. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61319. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Votintseva A.A., Miller R.R., Fung R. Multiple-strain colonization in nasal carriers of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:1192–1200. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03254-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller R.R., Walker A.S., Godwin H. Dynamics of acquisition and loss of carriage of Staphylococcus aureus strains in the community: the effect of clonal complex. J Infect. 2014;68:426–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.VandenBergh M.F., Yzerman E.P., van Belkum A. Follow-up of Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage after 8 years: redefining the persistent carrier state. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3133–3140. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.10.3133-3140.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nouwen J.L., Ott A., Kluytmans-Vandenbergh M.F. Predicting the Staphylococcus aureus nasal carrier state: derivation and validation of a “culture rule”. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:806–811. doi: 10.1086/423376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wertheim H.F., Melles D.C., Vos M.C. The role of nasal carriage in Staphylococcus aureus infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:751–762. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70295-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kluytmans J.A., Mouton J.W., Ijzerman E.P. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus as a major risk factor for wound infections after cardiac surgery. J Infect Dis. 1995;1:216–219. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.1.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Eiff C., Becker K., Machka K. Nasal carriage as a source of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:11–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wertheim H.F., Vos M.C., Ott A. Risk and outcome of nosocomial Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia in nasal carriers versus non-carriers. Lancet. 2004;364:703–705. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16897-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bode L.G., Kluytmans J.A., Wertheim H.F. Preventing surgical-site infections in nasal carriers of Staphylococcus aureus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:9–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deeny S.R., Cooper B.S., Cookson B. Targeted versus universal screening and decolonization to reduce healthcare-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. J Hosp Infect. 2013;85:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson D.J., Podgorny K., Berríos-Torres Strategies to prevent surgical site infections in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35:605–627. doi: 10.1086/676022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Humphreys H., Becker K., Dohmen P.M. Staphylococcus aureus and surgical site infections: benefits of screening and decolonization before surgery. J Hosp Infect. 2016;94:295–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gamblin J., Jefferies J.M., Harris S. Nasal self-swabbing for estimating the prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus in the community. J Med Microbiol. 2013;62:437–440. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.051854-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akmatov M.K., Mehraj J., Gatzemeier A. Serial home-based self-collection of anterior nasal swabs to detect Staphylococcus aureus carriage in a randomized population-based study in Germany. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;25:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Cleef B.A., van Rijen M., Ferket M., Kluytmans J.A. Self-sampling is appropriate for detection of Staphylococcus aureus: a validation study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2012;1:34. doi: 10.1186/2047-2994-1-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Votintseva A.A., Fung R., Miller R.R. Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus protein A (spa) mutants in the community and hospitals in Oxfordshire. BMC Microbiol. 2014;14:63. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-14-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mertz D., Frei R., Jaussi B. Throat swabs are necessary to reliably detect carriers of Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:475–477. doi: 10.1086/520016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaasch A.J., Barlow G., Edgeworth J.D. Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection: a pooled analysis of five prospective, observational studies. J Infect. 2014;68:242–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young B.C., Golubchik T., Batty E.M. Evolutionary dynamics of Staphylococcus aureus during progression from carriage to disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:4550–4555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113219109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang S.S., Septimus E., Kleinman K. Targeted versus universal decolonization to prevent ICU infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2255–2265. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee B.Y., Bartsch S.M., Wong K.F. Beyond the intensive care unit (ICU): countywide impact of universal ICU Staphylococcus aureus Decolonization. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183:480–489. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.