Abstract

Objective

To report the use of a stent-retriever in the management of vasospasm secondary to craniopharyngioma resection. Postoperative improvement was seen both clinically and on perfusion imaging.

Methods

A patient was admitted for resection of a large craniopharygioma. On day 6 postoperatively the patient had an acute hemiparesis. A computed tomography angiogram and perfusion scan demonstrated acute right-sided cerebral vasospasm and a perfusion defect in the territory of the middle cerebral artery (MCA).

Results

A pREset 4 × 20 mm stent-retriever was used to dilate the M1 and proximal M2 segments of the right MCA mechanically. This resulted in immediate dilatation of the spastic segment and improvement in the transit time on the angiogram. There was an improvement in the clinical status post-procedure and a computed tomography perfusion performed 24 hours after the procedure showed symmetrical perfusion. A computed tomography angiogram and magnetic resonance imaging performed 1 week later showed a symmetrical appearance to the MCA and no evidence of restricted diffusion.

Conclusion

The use of commercially available stent-retrievers can cause mechanical dilatation of vasospastic vessels. The stents do not need to be deployed for a prolonged period nor do they need to be implanted to have a prolonged dilatory effect on the spastic vessels.

Keywords: Cerebral vasospasm, stent-retriever, computed tomography perfusion, tumour

Introduction

Cerebral vasospasm is well known to occur after tumour resections as well as after aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. In the latter case it is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality for patients admitted to specialist neurosurgical units.1,2 Subarachnoid haemorrhage following tumour resection has also been well described although the literature on iatrogenic cerebral vasospasm is relatively sparse. A higher incidence of cerebral vasospasm has been correlated with increasing tumour size, total operative time, vessel encasement, vessel narrowing/compression and preoperative embolization.3 The mainstay of treatment for patients who develop symptomatic cerebral vasospasm from either cause is hypertension, hypervolaemia and haemodilution (HHH therapy) and for those who do not respond endovascular treatment options should be considered. These have traditionally included intra-arterial vasodilators such as nimodipine or verapamil and balloon angioplasty. Recently, a case series of patients treated with stent-retrievers was published.4 They showed good angiographic results and no complications. Here we present our case of post-craniopharyngioma resection cerebral vasospasm successfully treated with a stent-retriever with pre and postoperative computed tomography (CT) perfusion imaging to demonstrate the improvement in flow. This is the first published case to demonstrate CT perfusion changes after the treatment of cerebral vasospasm with stent-retrievers.

Case report

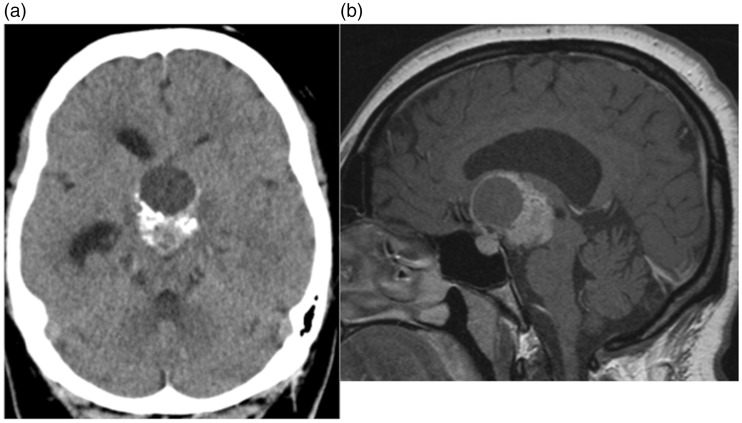

A 28-year-old female patient with no past medical history underwent routine CT imaging of the head for chronic headaches, which had been gradually increasing in frequency over the last 12–18 months. She reported occasionally blurring of her vision and that she kept ‘bumping into things’ but no other neurological symptoms. The clinical examination revealed a temporal field defect and undiagnosed diabetes insipidus but no other clinical signs. A routine CT scan of the head demonstrated a large partially solid, partially cystic and part calcified mass in the suprasellar region (Figure 1(a)). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed the mass lesion to be partially enhancing (Figure 1(b)) consistent with a likely craniopharyngioma. After a multidisciplinary team meeting and discussion with the patient, resection of the tumour was planned.

Figure 1.

A solid/cystic mass that demonstrates partial calcification can be seen in the midline (a). On magnetic resonance imaging enhancement can be seen as can the relationship of the mass to the sella turcica (b).

Using a right pteronial, subfrontal approach the tumour was partially resected. The tumour was dissected and resected through the interoptic space, the carotico-optic space and predominantly via the lamina terminalis. A small, anticipated amount of haemorrhage was noted during the operation and there was minimal spillage of tumour contents and no damage to the anterior circulation vessels. There were no intra-operative complications. The tumour was very adherent to the optic radiation, which limited the resection.

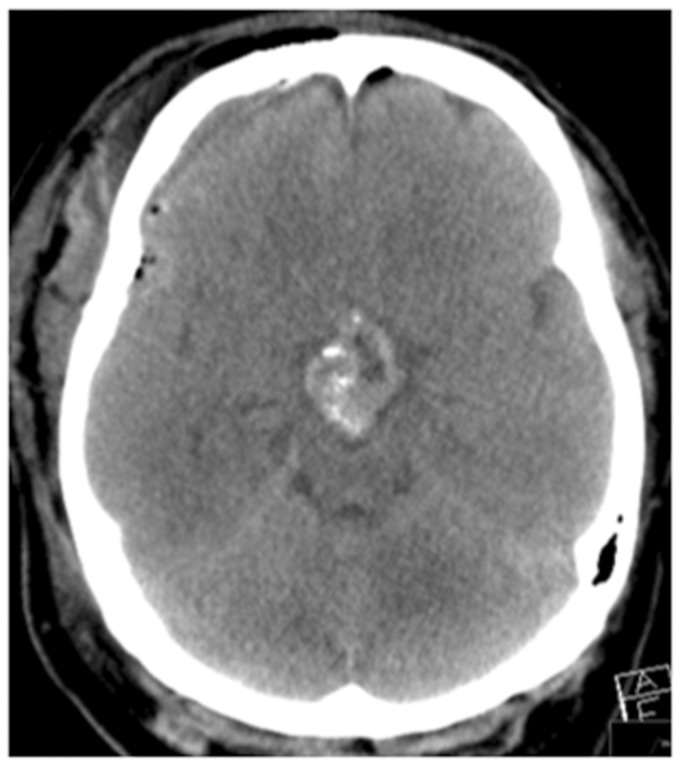

The patient was extubated without complication and there was no new neurological deficit initially. Postoperative MRI showed a considerable reduction in the volume of the tumour, with no evidence of infarction and haemorrhage in the Sylvian fissure on the right (Figure 2). The patient was started on oral nimodipine (60 mg every 4 hours) because of the subarachnoid haemorrhage seen on the postoperative MRI scan. On postoperative day 6 the patient developed an acute left hemiparesis principally of the upper limb. An emergency CT and CT angiogram were performed, which revealed severe cerebral vasospasm on the right that involved the middle cerebral artery (MCA) and anterior cerebral artery (ACA). The patient underwent perfusion imaging which showed a large hypoxic region within the territory of the MCA but no definite infarct core. There was no definite established infarction on the plain CT scan (Figure 3). The systolic blood pressure was increased (>160 mmHg); however, this did not result in symptomatic improvement and therefore endovascular treatment was decided on.

Figure 2.

The postoperative imaging showed a considerable decrease in the volume of tumour tissue. (a) T1-weighted sagittal and (b) T2-weighted coronal images, and no evidence of infarction. On the coronal T1-weighted sequence (c) haemorrhage was seen in the Sylvian fissure in the right and this was believed to be the cause of delayed spasm in our case.

Figure 3.

Severe vasospasm can be seen affecting the right middle cerebral artery (MCA) and right anterior cerebral artery (a), with decreased cerebral blood flow and prolonged transit time seen within the territory of the right MCA on the computed tomography perfusion scan (b).

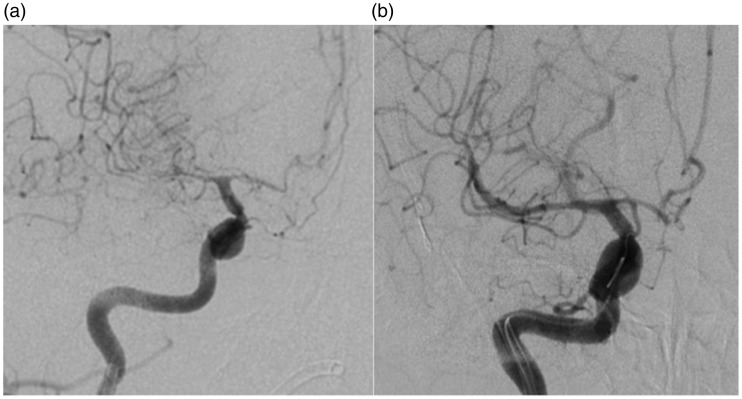

Under full anaesthesia and using a right common femoral approach a 6 Fr guide catheter was tracked into the right internal carotid artery after full heparinisation with a 5000 IU bolus. Angiography revealed severe vasospasm of the M1 and proximal M2 branches as well as further spasm in the A1 segment with a prolonged transit time (Figure 4(a)). A Prowler Select plus was carefully tracked into the M2 branch (angular artery) and a pREset 4 × 20 mm (phenox, Bochum) was deployed in the M2 and M1 segment for 3 minutes. The stent was then recaptured and angiography demonstrated a significant improvement in the calibre of the M1 and M2 segments where the stent had been deployed (Figure 4(b)). There was a concomitant improvement in the transit time. The calibre of the A1 segment also improved although the stent had not been deployed in this segment and intra-arterial vasodilators were not infused.

Figure 4.

Angiography of the right internal carotid artery revealed severe vasospasm of the right M1, A1 and M2 branches (a) with a prolonged transit time consistent with the findings of the computed tomography (CT) angiogram and CT perfusion study. Following stent deployment in the right M1 and M2 branches there was a significant improvement in the calibre of the vessels including the A1 segment (the stent was not deployed in the A1 segment and intra-arterial vasodilators were not infused) (b).

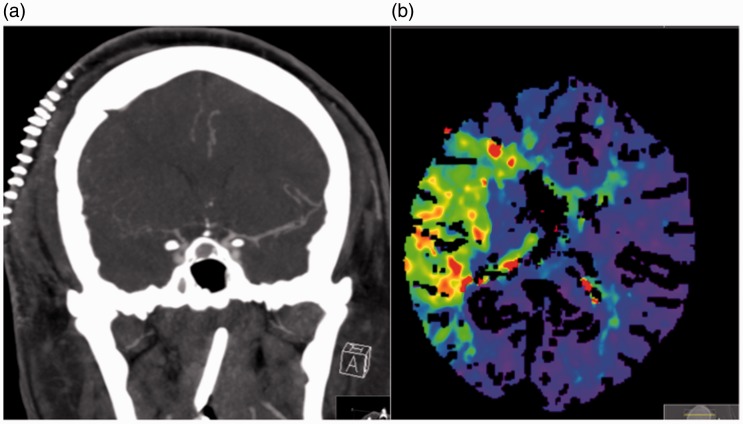

The patient woke and the hemiparesis had resolved. A CT perfusion scan performed 24 hours after the procedure revealed symmetrical perfusion and a CT angiogram performed 7 days (Figure 5) after the procedure showed normal vessel calibre bilaterally. There was no evidence of established infarction on the MRI scan. The patient was discharged with no new neurological deficits.

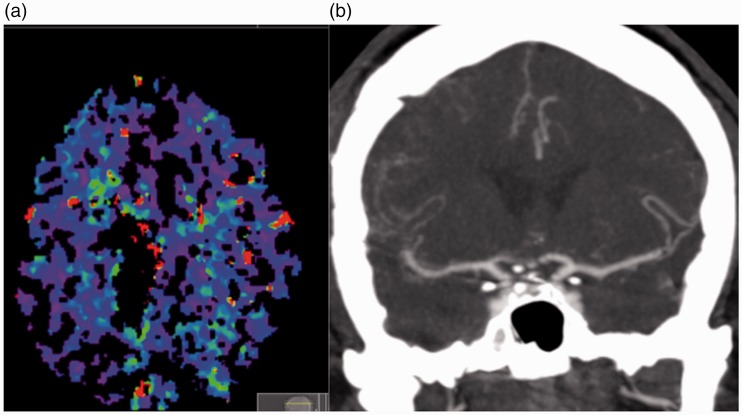

Figure 5.

A computed tomography (CT) perfusion scan (a) performed 24 hours after the stent-plasty procedure showed symmetrical perfusion (the image degradation was secondary to patient movement during the acquisition). A CT angiogram performed 7 days post-stent-plasty shows normal calibre to the M1 segment of the middle cerebral artery bilaterally.

Discussion

Krayenbühl was the first to describe cerebral vasospasm after a craniotomy for tumour resection in two patients – one with a pituitary adenoma and another with a vestibular schwannoma.5 Since then further reports have also been published although cerebral vasospasm remains a relatively uncommon complication after the resection of intracranial tumours. Bejjani et al.3 published their series of 470 consecutive patients with cranial base tumours and they showed an incidence of postoperative spasm of only 1.9%. The typical interval between tumour resection and the onset of symptomatic vasospasm is remarkably similar to that of aneurysmal delayed vasospasm and occurs typically at days 7–8 postoperatively,6 and it is not unreasonable to suspect a similar underlying mechanism is involved in the pathogenesis of the vasospasm in both these situations. This is similar in our case in which the patient developed cerebral spasm on day 6 postoperatively. The morbidity and mortality can be high in those patients who develop cerebral vasospasm, with almost 50% of patients having persistent neurological deficits and 30% mortality.3,7–25 The high morbidity and mortality associated with cerebral vasospasm secondary to tumour resection means that clinicians involved in the management of these patients must be vigilant for any neurological decline that could be attributed to vasospasm. The spasm can occur early as in our case and therefore imaging should be considered earlier rather than later, especially as the early management of vasospasm has been associated with outcomes.26 Multiple factors have been associated with the development of vasospasm following tumour resection and these are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Risk factors for developing vasospasm following tumour resection.

| • Intra-operative haemorrhage and subarachnoid haemorrhage |

| • Preoperative vessel encasement and vessel compression/narrowing |

| • Sellar location and supra-sellar extension |

| • Mechanical stretching and manipulation, particularly of the vasculature |

| • Hypothalamic dysfunction |

| • Spillage of tumour contents |

| • Vasoactive materials and antigens released by the tumour, e.g. platelet-derived growth factor |

| • Meningitis |

The initial management of patients with cerebral vasospasm involves HHH therapy (hypertension, hypervolaemia and haemodilution) although hypertension appears to be the most beneficial of these.27–29 Those patients that fail to improve with these measures should be considered for more invasive treatment options that have classically consisted of intra-arterial vasodilators and/or balloon angioplasty. More recently the use of stent-retrievers to treat cerebral vasospasm secondary to subarachnoid haemorrhage was described.4 Although a good angiographic response was seen the clinical outcome of the patients was not reported. In addition, advanced imaging techniques were not utilised to assess the physiological effects of the vasospasm or the treatment. Furthermore, in several of the cases intra-arterial nimodipine was also infused during the stent-plasty, which may have confounded the results. In our case we report not only an acute deterioration in the clinical status of the patient following the surgery but we also demonstrate the reduced perfusion within the territory of the vasospastic MCA. The stent deployment in our case lasted approximately 3 minutes as compared to 20 minutes, as was described in some of the previously published cases.4 Interestingly, the calibre of the A1 segment also improved following the stent-plasty and the exact mechanism of this is unknown; however, this was reported in the previous case series4 (case 3) and in animal studies30 and it is possible that this may be a flow-related phenomenon. In addition, no intra-arterial vasodilating compounds were injected during the procedure, which demonstrates that the vasodilatation and improved perfusion were secondary to the mechanical dilatation of the stent alone. The clinical symptoms of the patient resolved after the stent-plasty procedure and the CT perfusion scan was performed to confirm persistent symmetrical perfusion with longer-term persistent calibre change seen on the delayed CT angiogram performed 1 week postoperatively. These studies demonstrate the durability of the stent-plasty technique that avoids the need for repeat infusion of intra-arterial vasodilating compounds, which may otherwise be required in order to maintain vascular dilatation.

Conclusion

In this case we demonstrate that cerebral vasospasm can occur after tumour resection and that this should be excluded in patients with deteriorating neurology. This is the first case to demonstrate improvements in perfusion following stent-plasty treatment.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: PB is consultant for phenox (Bochum, Germany) and co-inventor and patent holder of the Lumenate Stent. The other authors have no conflict of interest.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Kassell NF, Torner JC, Haley EC, et al. The International Cooperative Study on the Timing of Aneurysm Surgery. Part 1: Overall management results. J Neurosurg 1990; 73: 18–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kassell NF, Sasaki T, Colohan AR, et al. Cerebral vasospasm following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke J Cereb Circ 1985; 16: 562–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bejjani GK, Sekhar LN, Yost AM, et al. Vasospasm after cranial base tumor resection: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. Surg Neurol 1999; 52: 577–583. discussion 583–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhogal P, Loh Y, Brouwer P, et al. Treatment of cerebral vasospasm with self-expandable retrievable stents: proof of concept. J Neurointervent Surg 2016. Epub ahead of print 14 July 2014, DOI: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2016-012546. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Krayenbuehl H. [A contribution to the problem of cerebral angiospastic insult]. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1960; 90: 961–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oyama K, Criddle L. Vasospasm after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Crit Care Nurse 2004; 24: 58–60, 62, 64–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aoki N, Origitano TC, al-Mefty O. Vasospasm after resection of skull base tumors. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1995; 132: 53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aw D, Aldwaik MA, Taylor TR, et al. Intracranial vasospasm with delayed ischaemic deficit following epidermoid cyst resection. Br J Radiol 2010; 83: e135–e137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Almubaslat M, Africk C. Cerebral vasospasm after resection of an esthesioneuroblastoma: case report and literature review. Surg Neurol 2007; 68: 322–328. discussion 328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Camp PE, Paxton HD, Buchan GC, et al. Vasospasm after trans-sphenoidal hypophysectomy. Neurosurgery 1980; 7: 382–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang SD, Yap OW, Adler JR. Symptomatic vasospasm after resection of a suprasellar pilocytic astrocytoma: case report and possible pathogenesis. Surg Neurol 1999; 51: 521–526. discussion 526–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Almeida GM, Bianco E, Souza AS. Vasospasm after acoustic neuroma removal. Surg Neurol 1985; 23: 38–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ecker RD, Atkinson JL, Nichols DA. Delayed ischemic deficit after resection of a large intracranial dermoid: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery 2003; 52: 706–710. discussion 709–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman JA, Meyer FB, Wetjen NM, et al. Balloon angioplasty to treat vasospasm after transsphenoidal surgery. Case illustration. J Neurosurg 2001; 95: 353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hyde-Rowan MD, Roessmann U, Brodkey JS. Vasospasm following transsphenoidal tumor removal associated with the arterial changes of oral contraception. Surg Neurol 1983; 20: 120–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasliwal MK, Srivastava R, Sinha S, et al. Vasospasm after transsphenoidal pituitary surgery: a case report and review of the literature. Neurol India 2008; 56: 81–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LeRoux PD, Haglund MM, Mayberg MR, et al. Symptomatic cerebral vasospasm following tumor resection: report of two cases. Surg Neurol 1991; 36: 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macdonald RL, Hoffman HJ. Subarachnoid hemorrhage and vasospasm following removal of craniopharyngioma. J Clin Neurosci Off J Neurosurg Soc Australas 1997; 4: 348–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mawk JR. Vasospasm after pituitary surgery. J Neurosurg 1983; 58: 972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mawk JR, Ausman JI, Erickson DL, et al. Vasospasm following transcranial removal of large pituitary adenomas. Report of three cases. J Neurosurg 1979; 50: 229–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishioka H, Ito H, Haraoka J. Cerebral vasospasm following transsphenoidal removal of a pituitary adenoma. Br J Neurosurg 2001; 15: 44–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Origitano TC, al-Mefty O, Leonetti JP, et al. Vascular considerations and complications in cranial base surgery. Neurosurgery 1994; 35: 351–362. discussion 362–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Popugaev KA, Savin IA, Lubnin AU, et al. Unusual cause of cerebral vasospasm after pituitary surgery. Neurol Sci Off J Ital Neurol Soc Ital Soc Clin Neurophysiol 2011; 32: 673–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puri AS, Zada G, Zarzour H, et al. Cerebral vasospasm after transsphenoidal resection of pituitary macroadenomas: report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Neurosurgery 2012; 71(1 Suppl Operative): 173–180. discussion 180–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taussky P, Kalra R, Couldwell WT. Delayed vasospasm after removal of a skull base meningioma. J Neurol Surg Part Cent Eur Neurosurg 2012; 73: 249–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenwasser RH, Armonda RA, Thomas JE, et al. Therapeutic modalities for the management of cerebral vasospasm: timing of endovascular options. Neurosurgery 1999; 44: 975–979. discussion 979–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raabe A, Beck J, Keller M, et al. Relative importance of hypertension compared with hypervolemia for increasing cerebral oxygenation in patients with cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg 2005; 103: 974–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muench E, Horn P, Bauhuf C, et al. Effects of hypervolemia and hypertension on regional cerebral blood flow, intracranial pressure, and brain tissue oxygenation after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Crit Care Med 2007; 35: 1844–1851. quiz 1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tu YK, Kuo MF, Liu HM. Cerebral oxygen transport and metabolism during graded isovolemic hemodilution in experimental global ischemia. J Neurol Sci 1997; 150: 115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kobayashi H, Ide H, Aradachi H, et al. Histological studies of intracranial vessels in primates following transluminal angioplasty for vasospasm. J Neurosurg 1993; 78: 481–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]