Abstract

Depression is a major issue in heart failure (HF). Depression is present in about one in five HF patients, with about 48 % of these individuals having significant depression. There is a wide variation in reported prevalences because of differences in the cohorts studied and methodologies. There are shared pathophysiological mechanisms between HF and depression. The adverse effects of depression on the outcomes in HF include reduced quality of life, reduced healthcare use, rehospitalisation and increased mortality. Results from metaanalysis suggest a twofold increase in mortality in HF patients with compared to those without depression. Pharmacological management of depression in HF has not been shown to improve major outcomes. No demonstrable benefits over cognitive behavioural therapy and psychotherapy have been demonstrated.

Keywords: Depression, heart failure, prevalence, management, outcomes

The prevalence of major depression in chronic heart failure (HF) is about 20–40 %, which is 4–5 % higher than in the normal population.[1–3] Depression in heart failure has become a major issue as the burden of heart failure has continued to increase, and many studies have suggested poorer outcomes in HF patients reporting depression.[4–8] The cost of managing HF has continued to escalate, and high rates of depression contribute to this.[9–13] The use of different methods for assessment (validated questionnaires and clinical interviews) and the effects of age, gender and race have contributed to variations in the prevalence figures reported. Antidepressant drug therapy has not yielded the desired outcomes. Even the use of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) has not shown a consistent improvement in outcomes, as demonstrated by two recent large trials.[14,15]

Prevalence

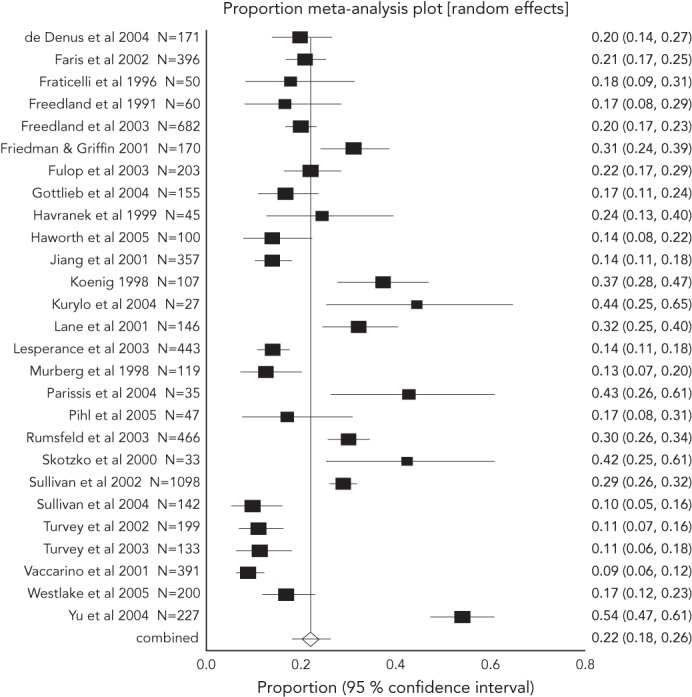

The aggregated point prevalence of depression in HF patients is about 21 %;[1] however, the figures reported in studies range from 9 to 60 %.[1] The aggregated prevalence for women is higher than for men, with 32.7 % (range 11–67 %) of women being depressed compared with 26.1 % (7–63 %) of men.[1] The prevalence of depression increases with New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, with the biggest difference seen between NYHA classes II and III (see Table 1).

Table 1: Prevalence of Depression in Patients with Heart Failure Based on New York Heart Association (NYHA) Functional Class.

| NYHA functional class | N* | Depression rate |

|---|---|---|

| I | 222 | 0.11 |

| II | 774 | 0.20 |

| III | 638 | 0.38 |

| IV | 155 | 0.42 |

Estimates compiled from five studies reporting depression rates specific to NYHA functional class. Adapted from Rutledge et al.[1] Permission to reproduce granted by Elsevier (© 2006).

The heterogeneity in the reported prevalence of depression is related to various factors, such as: the method of assessing depression (questionnaire versus structured interview); conservative versus liberal cut-offs for depression diagnosis; the severity of HF, mean patient age, ethnicity and gender; and inpatients versus outpatients.

The plethora of depression symptom inventories, including the Beck depression inventory,[16] Zung self-rating depression scale,[17] geriatric depression scale,[18] Center for Epidemiological Studies – depression scale,[19] hospital anxiety and depression scale,[20] inventory to diagnose depression,[21] Hamilton rating scale for depression,[22] Hopkins symptom checklist,[23] medical outcomes study – depression[24] and multiple affect adjective checklist,[25] has also contributed to the heterogeneity (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Prevalence of Depression in Heart Failure Patients and 95 % Confidence Intervals from 27 Studies.

Source: Rutledge et al.[1] Permission to reproduce granted by Elsevier (© 2006).

Pathophysiological Implications of Depression in Cardiovascular Disease

The adverse effects of depression on cardiovascular disease (CVD) are believed to be mediated by a shared pathophysiological mechanism. Natriuretic peptides in HF are altered in areas of the brain regulating blood pressure and fluid control in experimental animals.[26] Drugs used in the treatment of HF may reverse these changes.[27] Central natriuretic peptides have an antagonistic effect on blood pressure and fluid neurotransmitters in HF, and are associated with mental and emotional changes in HF.[28,29]

Depression may contribute to dysregulation of the autonomic system, with reduction in the parasympathetic and increase in the sympathetic tone and its attendant increase in heart rate, reduction in heart rate variability and lower threshold for myocardial ischaemia and adverse cardiac events in patients with CVD.[30,31] The heightened sympathetic tone is associated with increased levels of cortisol,[30] serotonin, renin, aldosterone, angiotensin and free radicals.[3] High levels of circulating catecholamines may also induce a procoagulant phase by increasing platelet activation[32,33] and inhibiting the synthesis of protective eicosanoids in response to the increased haemodynamic stress on the vascular wall.[34] Reduced inhibition of macrophage activation via the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway contributes to the elevation of pro-inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein and cytokines, such as interleukin-1beta, interleukin-6 and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha), in depression. TNF-alpha administration in healthy subjects has been shown to reduce serotonin levels and produce depressed mood, sleep disorders and malaise.[35,36]

A number of other mechanisms for poorer outcomes in depressed HF patients have been proposed in the literature. It has been suggested that inflammation may be responsible for worse outcomes in depressed HF patients.[37] High levels of inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6 and TNF-alpha, are independent predictors of HF-related deaths and exacerbations.[38–40] Despite this suggestion, however, the evidence linking outcomes in HF patients with depression to individual biomarkers is still debatable. Recently the effect of reduced blood flow to the hippocampus, which has an important role in emotion and memory, has been alluded to as a possible mechanism for depression and cognitive decline in patients with HF.[41] Experimentally there is strong evidence for the modulating role of the immune system on the relationship between depression and CVD via the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and the autonomic nervous system.[42]

Despite these interrelationships between depression and CVD, no causal relationship has yet been demonstrated. Most of the studies in this area were case-controlled or cross-sectional, but they did not control for behavioural mediators such as poor treatment adherence.

The Management of Depression in Heart Failure

There is still no consensus on the best way to treat HF patients with depression. Studies have shown improvement in depressive symptoms with the use of SSRIs;[14,15,43,44] however the large Setraline Against Depression and Heart Disease in Chronic Heart Failure (SADHART)[14] and Morbidity, Mortality and Mood in Depressed Heart Failure Patients (MOOD-HF)[15] trials failed to show any significant benefit over placebo. No clear benefits were shown between usual care (optimal HF treatment without antidepressants) and the use of SSRIs in SADHART or MOOD-HF.

Psychotherapy has been shown to reduce the depressive symptoms in CVD but has no effect on the major outcomes of the disease.[45] A small study comparing Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy with a web-based discussion forum did not demonstrate a significant difference in the management of depression in HF. There was, Survival (%) 60 40 however, a significant improvement in depressive symptoms of the Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy group when compared with baseline.[46]

Outcomes in Depressed Heart Failure Patents

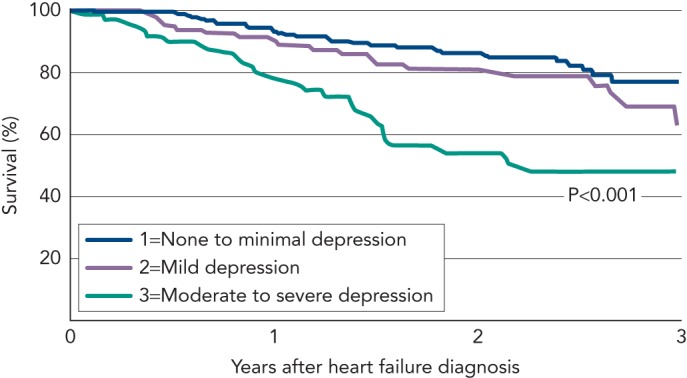

Studies have suggested a worse outcome in HF patients with depression across a broad range of events including mortality, healthcare use and associated clinical conditions, especially in more severely depressed patients (see Figure 2).[1,47] Depression was found to be an independent risk factor for mortality in HF, and this persists independent of NYHA class.[7]

Figure 2: All-cause Mortality in Heart Failure Patients by Severity of Depression.

Source: Adapted from Moraska et al.[47] Permission to reproduce granted by Wolters Kluwer Health (© 2013).

A recent large Danish study found depression to be related to all-cause mortality in patients with an ejection fraction ≤35 % but not in other types of HF.[48] There was no interaction between mortality and age, sex, HF cause, NYHA class or comorbidities. Depression in HF has also been shown to be the strongest predictor of short-term declines in health status, significant worsening of HF symptoms, physical and social functions, and quality of life.[8]

A meta-analysis of nine studies shows that the relationship between depression and mortality is dependent on the severity of depression: severe and not mild depression are associated with increased mortality.[49] The increased mortality related to depression in HF persists over a long period of time.[50] Depression is associated with death and readmission for HF, especially in patients with milder HF, a shorter duration of symptoms and lower blood pressures.[51]

There are a number of factors that could lead to the overestimation of the impact of depression on mortality. These include differences in the method of diagnosing depression, self-reported depression symptoms or antidepressant use, and inability to account for confounders such as smoking and alcohol use.[1,7,47]

Conclusion

Depression is a common finding in patients with HF and constitutes an additional burden on the management of these patients. Wide variations in reported prevalence rates are due to varied cohort characteristics and the multiplicity of instruments and methodologies used. The presence of depression, however, leads to poor outcomes, morbidity and mortality. Treatment with newer SSRIs, although effective, does not improve outcomes and is not superior to cognitive behavioural therapy and psychotherapy. There are still many knowledge gaps to fill and issues to be addressed.

References

- 1.Rutledge T, Reis VA, Link SE. Depression in heart failure: a meta-analytic review of prevalence, intervention effects and associations with clinical outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.055. 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konstram V, Moser DK, De Jong MJ. Depression and anxiety in heart failure. J Card Fail. 2005;11:455–463. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.03.006. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parissis JT, Fountoulaki K, Paraskedvaidis I et al. Depression in chronic heart failure: novel pathophysiological mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Expert Pin Investig Drugs. 2005;14:567–577. doi: 10.1517/13543784.14.5.567. 10.1517/13543784.14.5.567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD et al. ; Authors/Task Force Members. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2129–2200. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sullivan MD, Levy WC, Crane BA et al. Usefulness of depression to predict time to combined end point of transplant or death for outpatients with advanced heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:1577–1580. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.08.046. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.08.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang W, Alexander J, Christopher E et al. Relationship of depression to increased risk of mortality and rehospitalisation in patients with congestive heart failure. Arch Int Med. 2001;161:1849–1856. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.15.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Junger J, Schellberg D, Müller-Tasch T et al. Depression increasingly predicts mortality in congestive heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7:261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.05.011. 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rumsfield JS, Havranek E, Masoudi FA et al. ; Cardiovascular Outcome Research Consortium. Depressive symptoms are the strongest predictors of short-term declines in health status in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1811–1817. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sullivan M, Simon G, Spertus J et al. Depression-related costs in heart failure care. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1860–1866. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.16.1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cline CMJ, Israelsson BYA, Willenheimer RB et al. Cost effective management programme for heart failure reduces hospitalization. Heart. 1998;80:442–446. doi: 10.1136/hrt.80.5.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freedland KE, Rich MW, Skala JA et al. Prevalence of depression in heart failure patients. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:119–128. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000038938.67401.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mbakwem AC, Aina FO. Comparative study of depression in hospitalized and stable heart failure patients in an urban Nigerian teaching hospital. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:435–440. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.04.008. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gottlieb SS, Khatta M, Friedman E et al. The influence of age, gender and race on the prevalence of depression in heart failure patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1542–1549. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.10.064. 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.10.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Connor CM, Jiang W, Kuchibhatlla M et al. Safety and efficacy of sertraline for depression in patients with heart failure. Results of the SADHART-CHF (Setraline Against Depression and Heart Disease in Chronic Heart Failure) Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:692–699. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.068. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Angermann CE, Gelbrich G, Stork S et al. ; MOOD-HF Investigators. Rationale and design of a randomized, controlled, multicenter trial investigating the effects of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibition on morbidity, mortality and mood in depressed heart failure patients (MOOD-HF). Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9:1212–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.10.005. 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beck AT. Depression Inventory. Philadelphia, PA: Center for Cognitive therapy, 1978.

- 17.Zung WWK. A self-rating depression screening scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63–70. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yesavage JA, Brink TL et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982–1983;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radloff L. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–390. 10.1177/014662167700100306 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zigmond AS, Snath RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zimmereman M, Coryell M, Corenthal C et al. A self-report scale to diagnose major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:1076–1086. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800110062008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1967;6:278–246. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lipman RS, Covi L, Shapiro AK. The Hopkins symptom checklist (HSCL)-factors derived from the HSCL-90. J Affect Disord. 1979;1:9–24. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(79)90021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagel R, Lynch D, Tamburrino M. Validity of the medical outcomes study depression screener in family practice training centers and community settings. Fam Med. 1998;30:362–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zuckerman M, Lubin B. The Multiple Affect Adjective Check List. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Service, 1965.

- 26.Hu K, Gaudron P, Bahner U et al. Changes of atrial natriuretic peptide in brain areas of rats with chronic myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:H312–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.1.H312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu K, Bahner U, Gaudron P et al. Chronic effects of ACE-inhibition (quinapril) and angiotensin-II-type receptor blockade (losartan) on atrial natriuretic peptide in brain nuclei of rats with experimental myocardial infarction. Basic Res Cardiol. 2001;96:258–266. doi: 10.1007/s003950170056. 10.1007/s003950170056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ertl G, Hu K, Gaudron P et al. Remodeling of the heart post myocardial infarction: focus on central ANF. Basic Res Cardiol. 1997;92:82–84. doi: 10.1007/BF00805567. 10.1007/s003950050024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hemman-Lingen C, Binder L, Klinge M et al. High plasma levels of N-terminal pro-atrial natriuretic peptide associated with low anxiety in severe heart failure. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:517–522. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000073870.93003.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hughes JW, Watkins L, Blumenthal JA et al. Depression and anxiety symptoms are related to increased 24h-hour urinary norepinephrine excretion among healthy middle-aged women . J Psychosom Res. 2004;57:353–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.02.016. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Craney RM, Freeland KE, Veith RC. Depression, the autonomic nervous system and coronary heart disease. Pschosom Med. 2005;67:S29–33. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000162254.61556.d5. 10.1097/01.psy.0000162254.61556.d5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Musselman DL, Tomer A, Mnatunga AK et al. Exaggerated platelet activity in major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1313–1317. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.10.1313. 10.1176/ajp.153.10.1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruce EC, Musselman DL. Depression alteration in platelet function and ischaemic heart disease. Psychosome Med. 2005;67:S34–6. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000164227.63647.d9. 10.1097/01.psy.0000164227.63647.d9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ross R. Atherosclerosis – an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Capuron L, Ravaid A, Miller AH et al. Baseline mood and psychosocial characteristics of patients developing depressive symptoms during interleukin-2 and/or interferon-alpha cancer therapy. Brain Behav Immun. 2004;18:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2003.11.004. 10.1016/j.bbi.2003.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiong GL, Prybol K, Boyle SH et al. ; SADHART-CHF Investigators. Inflammation markers and Major Depressive Disorder in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure: Results from the Sertraline against Depression and Heart Disease in Chronic Heart Failure (SADHART-CHF) study. Psychosom Med. 2015;77:808–815. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000216. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kop WJ, Synowski SJ, Gottlieb SS. Depression in heart failure: biobehavioral mechanisms. Heart Fail Clin. 2011;7:23–38. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2010.08.011. 10.1016/j.hfc.2010.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orus J, Roig E, Perez-Villa F et al. Prognostic value of serum cytokines in patients with congestive heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2000;19:419–425. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(00)00083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rauchhaus M, Doehner W, Francis DP et al. Plasma cytokine parameters and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2000;102:3060–3067. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.25.3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pasic J, Levy WC, Sullivan MD. Cytokines in depression and heart failure. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:181–193. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000058372.50240.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suzuki H, Matsumoto Y, Ota H et al. Hippocampal blood flow abnormality associated with depressive symptoms and cognitive impairment in patients with chronic heart failure. Circ J. 2016;80:1773–1780. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-16-0367. 10.1253/circj.CJ-16-0367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kop WJ, Gottdiener JS. The role of the immune system parameters in the relationship between depression and coronary artery disease. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:S37–41. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000162256.18710.4a. 10.1097/01.psy.0000162256.18710.4a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gottlieb SS, Kop WJ, Thomas SA et al. A double blind placebo controlled pilot study of controlled release paroxetine on depression and quality of life in chronic heart failure. Am Heart J. 2007;153:868–873. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.02.024. 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.02.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laspérance F, Frasure-Smith N, Laliberté MA et al. An open label study of nefazodone treatment of major depression in congestive heart failure. Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48:695–701. doi: 10.1177/070674370304801009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bechman LF, Blumenthal J, Burg M et al. ; Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients Investigators (ENRICHD). Effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction: the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289:3106–3116. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3106. 10.1001/jama.289.23.3106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lundgren JG, Dahlström O, Andersson G et al. The effect of guided web-based cognitive behavioral therapy on patients with depressive symptoms and heart failure: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:e194. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5556. 10.2196/jmir.5556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moraska AR, Chamberlain AM, Shah ND et al. Depression, healthcare utilization and death in heart failure: a community study. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:387–394. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.000118. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.000118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adelborg K, Schimidt M, Sundboll J et al. Mortality risk among heart failure patients with depression: A nationwide population-based cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e004137.. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004137. 10.1161/JAHA.116.004137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fan H, Yu W, Zhang Q et al. Depression after heart failure and risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2014;63:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.03.007. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adams J, Kuchibhatla M, Christopher EJ et al. Association of depression and survival in patients with chronic heart failure over 12 years. Psychosomatics. 2012;53:339–346. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2011.12.002. 10.1016/j.psym.2011.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Faris R, Purcell H, Henein MY et al. Clinical depression is common and significantly associated with reduced survival in patients with non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail. 2002;4:541–551. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(02)00101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]