Abstract

Uterine fibroids, also known as uterine leiomyoma (UL), are monoclonal tumors of the smooth muscle tissue layer (myometrium) of the uterus. Although ULs are considered benign, uterine fibroids are the source of major quality-of-life issues for approximately 25% of all women, who suffer from clinically significant symptoms of UL. Despite the prevalence of UL, there is no treatment option for UL which is long term, cost-effective, and leaves fertility intact. The lack of understanding about the etiology of UL contributes to the scarcity of medical therapies available. Studies have identified an important role for sex steroid hormones in the pathogenesis of UL, and have driven the use of hormonal treatment for fibroids, with mixed results. Dysregulation of cell signaling pathways, miRNA expression, and cytogenetic abnormalities have also been implicated in UL etiology. Recent discoveries on the etiology of UL and the development of relevant genetically modified rodent models of UL have started to revitalize UL research. This review outlines the major characteristics of fibroids; major contributors to UL etiology, including steroid hormones; and available preclinical animal models for UL.

Keywords: uterine leiomyoma, uterine fibroids, cell signaling pathways

Uterine Leiomyoma

Uterine Leiomyoma Characteristics

Uterine leiomyomas (ULs), or uterine fibroids, are steroid hormone-responsive, benign monoclonal tumors of the smooth muscle compartment (myometrium) of the uterus.1 As the most common reproductive tract tumor in women, ULs present a major quality-of-life problem for a large fraction of the population. It is estimated that up to 77% of all women will develop UL in their lifetime and 15 to 30% of these women suffer from substantial symptoms, including pelvic discomfort, dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, anemia, urinary incontinence, recurrent pregnancy loss, preterm labor, and in some cases infertility.2,3 In 10 to 40% of pregnancies with UL present, complications occur and miscarriage is up to twofold higher in women with symptomatic UL.4

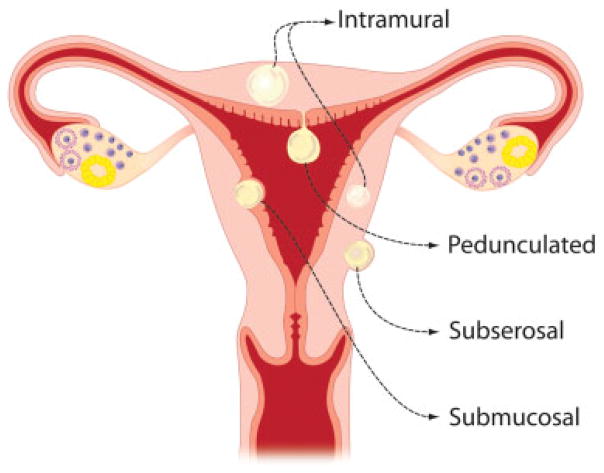

The location of UL within the uterus contributes to the symptoms presented. ULs are classified as subserosal, intramural, submucosal, or pedunculated depending on their location (Fig. 1).3 Submucosal ULs are most likely to cause menorrhagia, interfere with fertility, and can cause preterm birth or miscarriage.5 Large submucosal ULs can lead to pressure on adjacent organs resulting in pain, urinary symptoms, and constipation.6 Submucosal ULs also lead to lower pregnancy, implantation, and delivery rates in women undergoing in vitro fertilization.4,7 There is evidence of cross talk from UL to adjacent endometrial cells that can lead to decreased endometrial receptivity and poor blastocyst implantation.8 In addition, it has been suggested that submucosal UL may disrupt normal uterine peristaltic movements and contractility, impeding sperm arrival at the oviducts, embryo movement into the uterus, or causing increased contractions leading to preterm labor.4

Fig. 1.

Schematic showing location of uterine leiomyoma within uterus.

ULs are characterized by increased proliferation of disordered smooth muscle cells, altered extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition, and enhanced responsiveness to sex steroid hormones.3 A defining characteristic of UL is the overproduction and the disorganized fibrous nature of ECM.1 Compared with myometrial tissue, ECM protein profiles in UL include increased collagens, fibronectin, and proteoglycans.9,10 Several studies have also found increased activation of pathways involved in the production of ECM, including transforming growth factor-β3 (TGF-β3), CD24, and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) in UL.11–14 Interestingly, the ECM proteoglycan dermatopontin (DPT), an important organizer of collagens, is decreased in UL as well as in keloids, a fibrous lesion with disordered ECM similar to UL tissue.15 In addition to altering the organization of ECM collagens, the low levels of DPT in UL may also contribute to altered TGF-β signaling in UL.16 Normal myometrial smooth muscle cells in culture grow uniformly and in parallel with the cells’ major axis, whereas UL cells form ball-like aggregates or nodules in culture, contributing to the disorganized nature of UL cells.17 The excessive ECM in UL tissue may contribute to the disorganized cellular structure of UL cells.

Etiology of Uterine Leiomyoma

Risk Factors

Despite the distressing symptoms and prevalence of UL, very little is known about the etiology of these tumors. ULs are most often diagnosed in the perimenopausal years, but can become symptomatic much earlier in some women. The incidence of UL declines after menopause.1 UL incidence increases with age, peaking in the early 40s.18,19 However, this could be a result of previously asymptomatic UL becoming more noticeable after years of growth and exposure to endogenous steroid hormones, or greater likelihood of older women to seek fertility-ending UL treatment.20 After menopause, ULs are present in comparable numbers to premenopausal women; however, these tumors tend to be smaller and often asymptomatic.21 Age at menarche has also been suggested to be a risk factor for UL, with an earlier age indicating higher risk of developing UL.22 Parity is also a UL risk factor, with a decrease in UL incidence relative to the number of live births.20,22,23 Both age at menarche and parity as risk factors could be attributed to levels of lifetime exposure to sex steroid hormones, although the exact reason is still unclear.

Lifestyle choices can have a significant impact on risk of UL development. Obesity, diet, lack of exercise, and smoking have been correlated with UL incidence. Several studies have shown that high body mass index (BMI) correlates with increased UL incidence.18,23–25 Notably, a study by Ross et al showed more than 20% increase in UL risk for every 10 kg increase in body weight,18 and Lumbiganon et al found a 6% increase of UL for each BMI unit increase.23 Diet and exercise have also been linked to UL incidence, although it is not well established whether these contribute to body weight or constitute a risk factor alone. A study by Chiaffarino et al showed a relationship between higher UL risk in women with diets high in red meat and lower incidence in those with a diet high in green vegetables.26

Race

ULs disproportionately appear in higher percentage in women of African American descent. Even after controlling for BMI, parity, socioeconomic status, and other risk factors, African American women have higher incidence, larger tumors at diagnosis, more severe symptoms, and earlier age at diagnosis than white, Hispanic, or Asian American women.19,27 The incidence of UL by age 50 is more than 80% among African American women, compared with 70% in Caucasian women.28 Women of African American descent seek treatment for fibroids more often than other ethnic groups in the United States. African American women are 2.4 times more likely to have a hysterectomy for treatment of fibroids and have a 6.8-fold higher rate of myomectomy treatment for removal of fibroids compared with Caucasian women.29 A study by Huyck et al looked at racial differences in UL severity in a study which included African American and Caucasian women who have a sister previously diagnosed with UL. Black women who participated in the study exhibited higher likelihood for some known UL risk factors, including earlier age at menarche and higher likelihood of being obese. However, black women participants also scored lower on other UL risk factors, including history of smoking and less consumption of red meat. Nevertheless, when other risk factors were controlled for, this study showed that African American women had a significantly younger age at diagnosis of UL, more severe pain associated with UL, and a higher UL rate compared with Caucasian women.30 African American women are also more likely to report that ULs interfere with relationships between significant others, family and friends, and report a higher negative impact on self-esteem and emotional issues.31 In a self-reporting study, African American women in the United States were 77% more likely to miss work due to severe UL symptoms than Caucasian women.31 Despite the disproportionate severity and incidence of UL in African American women, the underlying cause for the discrepancy is not well understood. More studies on the etiology of UL are needed to discover the reason for racial risk factors in UL.

Steroid Hormones

It is well established that ULs are sensitive to sex steroid hormones. UL in vivo and UL cells in culture are dependent on stimulation from hormones, especially estrogen, for growth and development.32 UL can become symptomatic starting after puberty, when endogenous estrogen levels rise, and ULs regress after menopause.33 Local uterine tissue concentrations of hormones and hormone receptors differ between UL and healthy myometrial tissue. ULs have higher concentrations of estradiol, aromatase, progesterone receptor (PR), and estrogen receptor-α (ER-α).28 Increased expression of ER-α and PR is independent of tumor size, can be heterogeneous within tumors of one patient, and is consistent throughout all the menstrual cycle phases.6 As such, ULs seem to have a hypersensitivity to sex steroid hormones, distinct from the normal myometrial response to estrogen and progesterone. While the normal myometrium has a limited response to estrogen, and becomes quiescent in the luteal phase, UL tissue shows an increase in estrogen-regulated genes in the luteal phase.34 In addition to this loss of temporal/cyclical regulation by estrogen, UL also grows in response to progesterone, which typically has a suppressive effect on the myometrium.35 It is not yet understood when this change in sensitivity to sex steroid hormones occurs in UL. Serum levels of estrogen and progesterone are similar in women with and without UL.28 However, African American women have 18% higher estradiol levels compared with Caucasians and no difference in progesterone levels.6

Although the growth of UL has been shown to be highly dependent on steroid hormones, the exact role of progesterone in UL pathogenesis is still poorly understood. Although estrogen has been shown to be essential for UL cell growth,36 progesterone treatment in vitro has been shown to be supporting of growth36,37 and also inhibitory.34 In addition, estrogen stimulation increases fibroid growth in the most commonly used UL animal model, the Eker rat, while progesterone does not stimulate growth in this mutant rodent model.38 However, studies in a xenograft mouse model with human UL inserted under the kidney capsule demonstrated that progesterone is necessary for UL growth.39 Despite conflicting results in cell culture and animal studies of progesterone action in UL, a strong support for progesterone involvement in UL growth comes from antiprogestin therapies. The antiprogestine drugs, such as RU-486, Proellex (CDB4124), ulipristal acetate (CDB2914), and mifepristone, cause regression of UL tumor size and symptoms as well as a decrease in ECM formation in UL.40–43 The selective PR modulator, asoprisnil, is also used as a short-term effective treatment for UL tumor symptoms and size.43–45 Low circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D among African American women has been associated with higher incidence of UL. Hence, supplementation of vitamin D3 has been suggested as a potential long-term therapeutic option for UL prevention and treatment.46–48

Environmental Estrogens and Uterine Leiomyoma

One of the major risk factors for the development of UL is prepubertal exposure to environmental estrogens, likely resulting in developmental reprogramming of the uterus.33 Also referred to as estrogen-like endocrine disrupting chemicals (EEDC), these environmental estrogens can alter the function of the endocrine system by binding hormone receptors, or by altered hormone synthesis and metabolism.49 The structural similarity with estrogen of many EEDCs, including dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), bisphenol-A (BPA), diethylstilbestrol (DES), genistein, dioxin, and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), can cause symptoms of developmental reprogramming, such as early age of menarche in girls.49 A prominent concern for both increased UL incidence and higher incidence of hormone-responsive breast cancer is the declining average age of menarche in recent years.50,51 This early onset of puberty increases the overall lifetime exposure to estrogen, which increases risk of UL development and can also lead to adverse health problems later in life, such as depression and obesity.52,53

Early exposure to the environmental estrogen DES can result in hyperresponsiveness to normal levels of estrogen hormone as an adult, and can result in higher UL risk.54,55 DES was first produced in the 1930s as a synthetic estrogen prescribed to pregnant women through the 1970s to prevent miscarriage and to ease morning sickness. DES daughters, exposed in utero to DES, present with clear cell adenocarcinomas, uterine structural difference, higher chance of preterm labor or ectopic pregnancy, infertility, and increased incidence of UL.54,55 Studies in rodent models show perinatal exposure to DES can cause developmental reprogramming of the female rat reproductive tract.56

An increased risk of UL development has been linked to early-life exposure to genistein, a common source of dietary phytoestrogen.57–59 Genistein is best known as a tyrosine kinase inhibitor of EGFR; however, it can also activate ERs to influence gene expression.60,61 Infants fed with soy-based formula have a 6- to 11-fold higher exposure to genistein based on body weight than the levels known to cause hormonal effects in adults.57,62 This high concentration of phytoestrogens in infant formula has an estrogenic effect in the female reproductive tract during the critical window of sensitivity to environmental estrogens, including re-estrogenization of vaginal cells at 6 months of age.63 Mice treated neonatally with genistein at 50 mg/kg/day, a level corresponding to serum concentrations in infants fed soy-based formula (6.8 μM), have disrupted cyclicity and ovulation and are infertile due to uterine and oviductal abnormalities.58 Rats treated prepubertally with genistein also show myometrial gene expression differences understood to prime the uterus for adverse consequences as adults.61

In addition to DES and genistein, there is evidence that phenolic environmental estrogens, including BPA, octylphenol (OP), and nonylphenol (NP), may be involved in UL pathogenesis. BPA is a synthetic estrogen used during manufacturing of plastic products and resins commonly found in packaging of foods.64 Differential levels of xenoestrogens in blood serum levels and urine concentrations of patients with and without UL show correlation between environmental estrogen exposures and UL incidence.65 In addition, UL cells in culture increase proliferation and show increased expression of genes involved in UL pathogenesis when treated with BPA.66 Studies on rodent models exposed to high levels of BPA have shown disrupted reproductive organ development, including delayed vaginal opening and delayed testicular descent,67,68 as well as hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal axis disruption69 and increased cancer risk.70 However, some studies show no effect of BPA on UL incidence at concentrations commonly found in adults.71 In summary, prepubertal exposure to environmental estrogenic compounds increase risk of UL and result in reprogramming of reproductive organs.

Cellular Etiology

Cytogenetic Abnormalities in Uterine Leiomyoma

Karyotypic abnormalities occur in 40 to 50% of ULs, and tumors from the same uterus often show different chromosomal changes.3 The most common abnormalities are translocations on chromosome 12; deletion on chromosomes 3q and 7q; trisomy 12; and rearrangements on chromosomes 6, 10, and 13.3 These chromosomal abnormalities may contribute to disruption of genes aberrantly expressed in UL, including HGMA2, ESR2, and RAD5.1 Recently, research on a somatic mutation (c.131G > A) in the mediator complex subunit 12 (MED12) has gained attention, as this is an important contributor to UL etiology. Mutations in exon 2 of MED12 are present specifically in approximately 70% of ULs, and not in surrounding myometrial tissue.72 MED12 is a highly conserved 250-kDa protein that is involved in the transcriptional regulation of the RNA polymerase II complex. MED12 is part of the CDK8 module, which, upon activation by cyclin C, phosphorylates the C-terminal domain of the large subunit of RNA polymerase II and inhibits formation of the transcriptional initiation complex.73 Mice expressing the c.131G > A MED12 mutation in the uterus show uterine hyperplasia, UL-like tumor formation, and genomic instability, demonstrating the importance of this mutation in UL etiology.74 However, the mechanisms that lead to MED12 mutations in the otherwise quiescent myometrial tissue is still unknown. In addition to MED12, a small percentage of ULs is due to familial genetic mutations in the Fumarate Hydrase (HLRCC) genes; however, these do not account for the vast majority of ULs. HRLCC mutations are present only in approximately 100 families worldwide.1

Dysregulation of microRNAs in Uterine Leiomyoma

Several miRNAs exhibit differential expression between normal myometrium and UL tissue. A study by Wang et al75 in 2007, revealed 45 miRNAs including the let-7 family, miR-21, miR-23b, miR-29b, and miR-197 were significantly dysregulated in UL compared with healthy myometrial tissue. In addition, a significant racial difference in miRNA expression between ULs from Caucasian and African American women, specifically miR-21, miR-23b, and miR-197, was found.75 A study by Marsh et al also identified 46 miRNAs differentially expressed between UL and myometrium, many of which were also dysregulated in other tumors.76 Since ULs are steroid hormone–sensitive tumors, of particular interest were miRNAs associated with sex-steroid hormones in breast and prostate cancers that were also found to be increased in UL, including miR-21, miR-34a, miR-125b, and miR-150. A study by Luo and Chegini77 identified 91 miRNAs differentially expressed in UL and found that 27 of those were similarly dysregulated in at least one of two studies by Marsh et al or Wang et al described earlier. Crucial in vivo evidence for the tumor suppressor function of miR29b was provided recently by Qiang et al using kidney capsule transplant model of UL.78

Cell Signaling Pathways in Uterine Leiomyoma

PI3K/AKT-mTOR Pathway

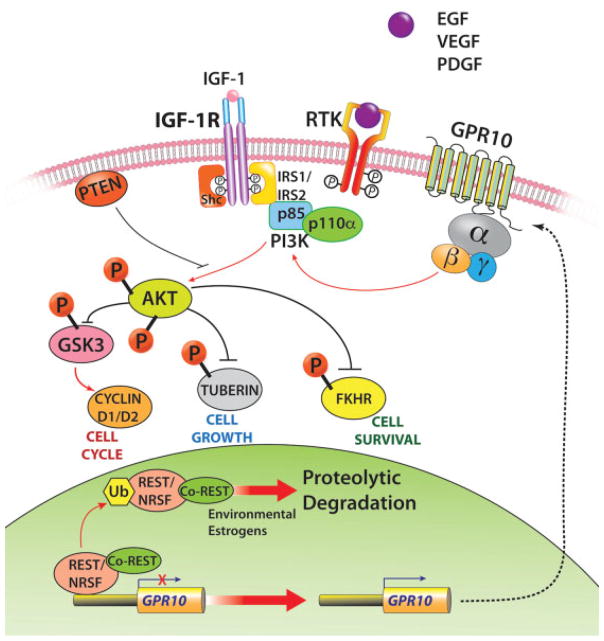

The PI3K/AKT-mTOR pathway has been identified as one of the most upregulated signaling pathways in UL, based on evidence from protein and transcriptional profiling of human UL, as well as in the Eker rat animal model.79 At the protein level, increased activation of PI3K/AKT pathway proteins and targets, including PTEN, p-AKT, p-GSK3, and CD2 proteins, in UL compared with myometrium shows involvement of PI3K/AKTsignaling in UL pathogenesis.80,81 In addition, there is evidence that PI3K and mTOR are necessary for estrogen-dependent cell growth in UL and myometrial cell cultures.82 Our studies indicated that the loss of tumor suppressor NRSF/REST and the ensuing expression of GPR10, a neuron-specific G-protein–coupled receptor, activates PI3K/AKT-mTOR pathway in UL (Fig. 2).83

Fig. 2.

Molecular pathways that promote uterine leiomyoma pathogenesis.

Targeting of the PI3K/AKT-mTOR pathway as a therapeutic option for UL is currently being explored by some laboratories.84,85 The AKT inhibitor, MK-2206, shows promise in the laboratory in limiting UL growth and increasing cell death.85 However, side effects of rash, diarrhea, fatigue, and mucositis in patients treated with MK-2206 are common due to the pervasive extent of AKT signaling in normal physiology.84 These side effects may limit the use of AKT inhibitor therapies for UL treatment.

Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK Pathway

The Ras/Raf/MEK (mitogen-activated protein kinase)/ERK (extracellular-signal–regulated kinase) pathway is involved in the regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation, and cell survival.86 Two members of the AP-1 family transcription factors activated by the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway, c-Fos and c-Jun, show lower levels of mRNA in UL compared with healthy myometrium.87,88 However, a role for increased Ras/Ref/MEK/ERK signaling in UL is likely, based on overexpression in UL of several proteins involved in the pathway. Shc, Grb2, and ERK and 15 distinct RTKs are more highly expressed in UL compared with healthy myometrium.89 In addition, a study by Nierth-Simpson et al showed that increased activation of ERK following estrogen treatment occurs in UL, but not in myometrial cells, again suggesting a possible role for the Ras/Ref/MEK/ERK signaling pathway in UL pathogenesis.90

WNT Signaling Pathway

There is some evidence of wingless-type (WNT) signaling in UL tumor etiology. In canonical WNT signaling, β-catenin accumulates in the nucleus and leads to activation of specific transcription factors.91 WNT signaling genes, including Wnt5b, are overexpressed in UL.92 WNT11 and WNT16 expression is increased specifically in UL cells after estrogen treatment.85 Studies by Ono et al91 have shown that inhibitors of WNT and β-catenin may block UL growth and proliferation, suggesting canonical WNT signaling may play a role in UL. Finally, studies by Tanwar et al have shown that constitutively active β-catenin drives UL-like tumors in the mouse uterus and may contribute to activation of TGF-β and mTOR signaling in these tumors.93

Growth Factors

Several growth factors appear to play a role in UL cell proliferation and tumor growth. Major growth factors overexpressed in UL include TGF-β, epidermal growth factor (EGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and IGF.28 Activation of TGF-β signaling has been identified as a major contributor to UL etiology, through smooth muscle cell proliferation and ECM deposition.85,94 Three distinct isoforms of TGF-β (TGF-β1, 2, and 3) occur in the myometrium. TGF-β1 and 2 are expressed at similar levels between the myometrium and UL tissue, whereas TGF-β3 is highly overexpressed in UL.94 A study by Arici and Sozen found a 3.5- to 5-fold higher expression of TGF-β3 in UL compared with myometrial cells, and treatment of cells with TGF-β led to increased fibronectin and cell proliferation in UL cells.13 Furthermore, treatment of the Eker rat, a UL animal model, with TGF-β inhibitors reduces severity and incidence of leiomyoma in these animals.95 Increased levels of phosphorylated SMAD 2/3 proteins in UL also suggest possible involvement of TGF-β in UL etiology.96 Interestingly, TGF-β expression in the uterus is sensitive to sex steroid hormones and acts downstream of environmental estrogen signaling, a prominent risk factor for UL development.97,98 TGF-β3 expression levels fluctuate during each phase of the menstrual cycle, peaking at the secretory phase, suggesting regulation by progesterone and estrogen.94

EGF, PDGF, and VEGF-A levels have been found at significantly higher levels in UL tissue compared with myometrial tissue, although the receptor for EGF (EGFR) is expressed at similar levels between the tissues.85,99 Overexpression of PDGF in UL has been linked to increased collagen α1 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), both of which are also increased in UL tissue.85 EGF stimulates DNA synthesis and increases mitogenesis through MAPK signaling pathways exclusively in UL tissue.28 Importantly, EGF expression seems to be highly regulated by steroid hormones, especially progesterone, and levels of EGF are drastically reduced upon GnRH-agonist treatment.20

Analysis of mRNA and protein of UL tissue shows that approximately one-third of UL patient samples have increased levels of IGF-1, which has been shown to stimulate mitogenesis by activating the MAPK signaling.28,85 Peng et al found a correlation between increased IGF-1 and increased activation of p-AKT in UL, levels of which also correlated with increased UL size.100 Studies in the Eker rat also indicate possible involvement of IGF-1 in UL pathogenesis. A study by Burroughs et al showed a sevenfold increase in IGF-1 levels in the Eker rat leiomyoma, as well as a significant increase of a protein downstream of IGF-1, insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) in UL.101 Finally, IGF-1 has also been shown to increase in UL-cultured cells after estrogen treatment.102 Thus, altered IGF-1 signaling may play a role in a considerable portion of UL.

Preclinical Animal Models for UL and the Future of Drug Discovery

The best characterized preclinical model for UL is the Eker rat. Eker rats have mutations in the tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (Tsc2) gene, involved in regulation of mTOR. These rats develop frequent spontaneous UL tumors in up to 65% of females at 15 months of age.103 Similar to human UL, Eker rat leiomyomas are highly estrogen sensitive and share biochemical and phenotypic profiles, including sex steroid hormone receptor expression, dysregulation of HMGA2, IGF-1, and the mTOR pathway, and histological features.1,79 In addition, a tumor cell line derived from the Eker rat, known as ELT3 cells, has been shown to retain their UL phenotype. These immortalized cells have been used extensively to explore possible therapeutic options for UL, including SERMs, antifibrotics, and antiprogestins.104 However, Eker rats also present with renal and liver cancers, which are often fatal and limit long-term studies.105 Similar to the Eker rat, a mouse model with mutations in the Tsc2 gene has been developed recently. This mouse model presents with UL, as well as myometrial tumors in the lungs.1,106 However, the Eker rat and Tsc2 null mice are not ideal preclinical models for UL, as the Tsc2 gene mutated in these animals is not affected in human UL.

Recently, a mouse model for Med12 c.131G > A missense mutation, which is frequently found in UL, has been developed.74 This mouse model expresses the mutant Med12 gene in the reproductive tract under Med12 conditional null background, driven by Amhr2+/Cre.72,74 These mice develop myometrial tumors that mimic UL at the histological level, including development of nodules with increased ECM as well as chromosomal instability. Further characterization of this mouse model will be important for understanding the emerging role of the common MED12 mutations in UL pathogenesis. Mice overexpressing human GPR10 in the myometrium83 as well as a conditional Rest knockout model (McWilliams, PhD and Chennathukuzhi, PhD, 2017 unpublished data) that we have developed recently also recapitulate molecular changes that occur in UL.

Other UL models include xenografts of human UL tumors in immune-compromised mice,107 and renal capsule transplant model39 for UL. These approaches are useful for studying tumor formation in vivo but lack myometrial controls, as the matched human myometrial cells do not form xenografts easily in this system.107 The guinea pig has also been used as an alternative mammalian model for UL, which forms frequent leiomyoma after ovary removal and estrogen treatment.108 However, these leiomyomas show little similarity to human UL based on histological studies.105

Uterine fibroids continue to be the primary indication for hysterectomy in the United States and account for more than 200,000 hysterectomies annually.1 In the year 2010, the estimated annual cost of uterine fibroids in the United States was $5.9 to 34.4 billion.109 While the use of GnRH agonists, selective ER modulators, aromatase inhibitors, and PR modulators has been reported for the short-term management of fibroid symptoms prior to surgery,110–112 currently there is no approved drug to treat uterine fibroids on a long-term basis. This deficiency could be attributed to our poor understanding of the molecular mechanisms that initiate or promote the pathogenesis of UL and the lack of preclinical models that recapitulate the molecular milieu of the disease. Thus, there is an urgent need to understand the etiology of UL and to develop relevant preclinical animal models that could validate targets for drug discovery in the near future.

References

- 1.Walker CL, Stewart EA. Uterine fibroids: the elephant in the room. Science. 2005;308(5728):1589–1592. doi: 10.1126/science.1112063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Catherino WH, Parrott E, Segars J. Proceedings from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development conference on the Uterine Fibroid Research Update Workshop. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(1):9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.08.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bulun SE. Uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(14):1344–1355. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1209993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cook H, Ezzati M, Segars JH, McCarthy K. The impact of uterine leiomyomas on reproductive outcomes. Minerva Ginecol. 2010;62(3):225–236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gambadauro P. Dealing with uterine fibroids in reproductive medicine. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;32(3):210–216. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2011.644357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stewart EA. Uterine fibroids. Lancet. 2001;357(9252):293–298. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03622-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pritts EA, Parker WH, Olive DL. Fibroids and infertility: an updated systematic review of the evidence. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(4):1215–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makker A, Goel MM. Uterine leiomyomas: effects on architectural, cellular, and molecular determinants of endometrial receptivity. Reprod Sci. 2013;20(6):631–638. doi: 10.1177/1933719112459221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barker NM, Carrino DA, Caplan AI, et al. Proteoglycans in leiomyoma and normal myometrium: abundance, steroid hormone control, and implications for pathophysiology. Reprod Sci. 2016;23(3):302–309. doi: 10.1177/1933719115607994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujisawa C, Castellot JJ., Jr Matrix production and remodeling as therapeutic targets for uterine leiomyoma. J Cell Commun Signal. 2014;8(3):179–194. doi: 10.1007/s12079-014-0234-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Catherino W, Salama A, Potlog-Nahari C, Leppert P, Tsibris J, Segars J. Gene expression studies in leiomyomata: new directions for research. Semin Reprod Med. 2004;22(2):83–90. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-828614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stewart EA, Friedman AJ, Peck K, Nowak RA. Relative overexpression of collagen type I and collagen type III messenger ribonucleic acids by uterine leiomyomas during the proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79(3):900–906. doi: 10.1210/jcem.79.3.8077380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arici A, Sozen I. Transforming growth factor-beta3 is expressed at high levels in leiomyoma where it stimulates fibronectin expression and cell proliferation. Fertil Steril. 2000;73(5):1006–1011. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(00)00418-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolańska M, Sobolewski K, Drozdzewicz M, Bańkowski E. Extracellular matrix components in uterine leiomyoma and their alteration during the tumour growth. Mol Cell Biochem. 1998;189(01/02):145–152. doi: 10.1023/a:1006914301565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Catherino WH, Leppert PC, Stenmark MH, et al. Reduced dermatopontin expression is a molecular link between uterine leiomyomas and keloids. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2004;40(3):204–217. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okamoto O, Fujiwara S, Abe M, Sato Y. Dermatopontin interacts with transforming growth factor beta and enhances its biological activity. Biochem J. 1999;337(Pt 3):537–541. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobayashi Y, Nikaido T, Zhai YL, et al. In-vitro model of uterine leiomyomas: formation of ball-like aggregates. Hum Reprod. 1996;11(8):1724–1730. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ross RK, Pike MC, Vessey MP, Bull D, Yeates D, Casagrande JT. Risk factors for uterine fibroids: reduced risk associated with oral contraceptives. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;293(6543):359–362. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6543.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marshall LM, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, et al. Variation in the incidence of uterine leiomyoma among premenopausal women by age and race. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90(6):967–973. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00534-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flake GP, Andersen J, Dixon D. Etiology and pathogenesis of uterine leiomyomas: a review. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111(8):1037–1054. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cramer SF, Patel A. The frequency of uterine leiomyomas. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990;94(4):435–438. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/94.4.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marshall LM, Spiegelman D, Goldman MB, et al. A prospective study of reproductive factors and oral contraceptive use in relation to the risk of uterine leiomyomata. Fertil Steril. 1998;70(3):432–439. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lumbiganon P, Rugpao S, Phandhu-fung S, Laopaiboon M, Vudhikamraksa N, Werawatakul Y. Protective effect of depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate on surgically treated uterine leiomyomas: a multicentre case–control study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;103(9):909–914. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1996.tb09911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marshall LM, Spiegelman D, Manson JE, et al. Risk of uterine leiomyomata among premenopausal women in relation to body size and cigarette smoking. Epidemiology. 1998;9(5):511–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato F, Nishi M, Kudo R, Miyake H. Body fat distribution and uterine leiomyomas. J Epidemiol. 1998;8(3):176–180. doi: 10.2188/jea.8.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiaffarino F, Parazzini F, La Vecchia C, Chatenoud L, Di Cintio E, Marsico S. Diet and uterine myomas. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94(3):395–398. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kjerulff KH, Langenberg P, Seidman JD, Stolley PD, Guzinski GM. Uterine leiomyomas. Racial differences in severity, symptoms and age at diagnosis. J Reprod Med. 1996;41(7):483–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parker WH. Etiology, symptomatology, and diagnosis of uterine myomas. Fertil Steril. 2007;87(4):725–736. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.01.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wechter ME, Stewart EA, Myers ER, Kho RM, Wu JM. Leiomyoma-related hospitalization and surgery: prevalence and predicted growth based on population trends. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(5):492.e1–492.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huyck KL, Panhuysen CI, Cuenco KT, et al. The impact of race as a risk factor for symptom severity and age at diagnosis of uterine leiomyomata among affected sisters. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(2):168.e1–168.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stewart EA, Nicholson WK, Bradley L, Borah BJ. The burden of uterine fibroids for African-American women: results of a national survey. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2013;22(10):807–816. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walker CL. Role of hormonal and reproductive factors in the etiology and treatment of uterine leiomyoma. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2002;57:277–294. doi: 10.1210/rp.57.1.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.D’Aloisio AA, Baird DD, DeRoo LA, Sandler DP. Early-life exposures and early-onset uterine leiomyomata in black women in the Sister Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(3):406–412. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maruo T, Ohara N, Wang J, Matsuo H. Sex steroidal regulation of uterine leiomyoma growth and apoptosis. Hum Reprod Update. 2004;10(3):207–220. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmh019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moravek MB, Yin P, Ono M, et al. Ovarian steroids, stem cells and uterine leiomyoma: therapeutic implications. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21(1):1–12. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmu048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barbarisi A, Petillo O, Di Lieto A, et al. 17-beta estradiol elicits an autocrine leiomyoma cell proliferation: evidence for a stimulation of protein kinase-dependent pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2001;186(3):414–424. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(2000)9999:999<000::AID-JCP1040>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoekstra AV, Sefton EC, Berry E, et al. Progestins activate the AKT pathway in leiomyoma cells and promote survival. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(5):1768–1774. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burroughs KD, Fuchs-Young R, Davis B, Walker CL. Altered hormonal responsiveness of proliferation and apoptosis during myometrial maturation and the development of uterine leiomyomas in the rat. Biol Reprod. 2000;63(5):1322–1330. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.5.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ishikawa H, Ishi K, Serna VA, Kakazu R, Bulun SE, Kurita T. Progesterone is essential for maintenance and growth of uterine leiomyoma. Endocrinology. 2010;151(6):2433–2442. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patel A, Malik M, Britten J, Cox J, Catherino WH. Mifepristone inhibits extracellular matrix formation in uterine leiomyoma. Fertil Steril. 2016;105(4):1102–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eisinger SH, Meldrum S, Fiscella K, le Roux HD, Guzick DS. Low-dose mifepristone for uterine leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(2):243–250. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02511-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murphy AA, Morales AJ, Kettel LM, Yen SS. Regression of uterine leiomyomata to the antiprogesterone RU486: dose-response effect. Fertil Steril. 1995;64(1):187–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim JJ, Kurita T, Bulun SE. Progesterone action in endometrial cancer, endometriosis, uterine fibroids, and breast cancer. Endocr Rev. 2013;34(1):130–162. doi: 10.1210/er.2012-1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chwalisz K, Larsen L, Mattia-Goldberg C, Edmonds A, Elger W, Winkel CA. A randomized, controlled trial of asoprisnil, a novel selective progesterone receptor modulator, in women with uterine leiomyomata. Fertil Steril. 2007;87(6):1399–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams AR, Critchley HO, Osei J, et al. The effects of the selective progesterone receptor modulator asoprisnil on the morphology of uterine tissues after 3 months treatment in patients with symptomatic uterine leiomyomata. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(6):1696–1704. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baird DD, Hill MC, Schectman JM, Hollis BW. Vitamin d and the risk of uterine fibroids. Epidemiology. 2013;24(3):447–453. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31828acca0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paffoni A, Somigliana E, Vigano’ P, et al. Vitamin D status in women with uterine leiomyomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(8):E1374–E1378. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu JL, Segars JH. Is vitamin D the answer for prevention of uterine fibroids? Fertil Steril. 2015;104(3):559–560. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roy JR, Chakraborty S, Chakraborty TR. Estrogen-like endocrine disrupting chemicals affecting puberty in humans–a review. Med Sci Monit. 2009;15(6):RA137–RA145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Herman-Giddens ME. Recent data on pubertal milestones in United States children: the secular trend toward earlier development. Int J Androl. 2006;29(1):241–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2005.00575.x. discussion 286–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Biro FM, Galvez MP, Greenspan LC, et al. Pubertal assessment method and baseline characteristics in a mixed longitudinal study of girls. Pediatrics. 2010;126(3):e583–e590. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Black SR, Klein DN. Early menarcheal age and risk for later depressive symptomatology: the role of childhood depressive symptoms. J Youth Adolesc. 2012;41(9):1142–1150. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9758-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jefferson WN, Patisaul HB, Williams CJ. Reproductive consequences of developmental phytoestrogen exposure. Reproduction. 2012;143(3):247–260. doi: 10.1530/REP-11-0369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patel SA, Sunde J. Primary non-clear-cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina in a diethylstilbestrol exposed woman. Mil Med. 2014;179(4):e461–e462. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mahalingaiah S, Hart JE, Wise LA, Terry KL, Boynton-Jarrett R, Missmer SA. Prenatal diethylstilbestrol exposure and risk of uterine leiomyomata in the Nurses’ Health Study II. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179(2):186–191. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Iguchi T, Kamiya K, Uesugi Y, Sayama K, Takasugi N. In vitro fertilization of oocytes from polyovular follicles in mouse ovaries exposed neonatally to diethylstilbestrol. In Vivo. 1991;5(4):359–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoey L, Rowland IR, Lloyd AS, Clarke DB, Wiseman H. Influence of soya-based infant formula consumption on isoflavone and gut microflora metabolite concentrations in urine and on faecal microflora composition and metabolic activity in infants and children. Br J Nutr. 2004;91(4):607–616. doi: 10.1079/BJN20031083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jefferson WN, Padilla-Banks E, Goulding EH, Lao SP, Newbold RR, Williams CJ. Neonatal exposure to genistein disrupts ability of female mouse reproductive tract to support preimplantation embryo development and implantation. Biol Reprod. 2009;80(3):425–431. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.073171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Adlercreutz H, Yamada T, Wähälä K, Watanabe S. Maternal and neonatal phytoestrogens in Japanese women during birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180(3 Pt 1):737–743. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70281-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cojocneanu Petric R, Braicu C, Raduly L, et al. Phytochemicals modulate carcinogenic signaling pathways in breast and hormone-related cancers. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:2053–2066. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S83597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Möller FJ, Ledwig C, Zierau O, et al. The rat prepubertal uterine myometrium and not the luminal epithelium is predominantly affected by a chronic dietary genistein exposure. Arch Toxicol. 2012;86(12):1899–1910. doi: 10.1007/s00204-012-0907-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Setchell KD, Zimmer-Nechemias L, Cai J, Heubi JE. Exposure of infants to phyto-oestrogens from soy-based infant formula. Lancet. 1997;350(9070):23–27. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)09480-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bernbaum JC, Umbach DM, Ragan NB, et al. Pilot studies of estrogen-related physical findings in infants. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116(3):416–420. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McGuinn LA, Ghazarian AA, Joseph Su L, Ellison GL. Urinary bisphenol A and age at menarche among adolescent girls: evidence from NHANES 2003–2010. Environ Res. 2015;136:381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shen Y, Xu Q, Ren M, Feng X, Cai Y, Gao Y. Measurement of phenolic environmental estrogens in women with uterine leiomyoma. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e79838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shen Y, Ren ML, Feng X, Cai YL, Gao YX, Xu Q. An evidence in vitro for the influence of bisphenol A on uterine leiomyoma. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;178:80–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ashby J, Tinwell H. Uterotrophic activity of bisphenol A in the immature rat. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106(11):719–720. doi: 10.1289/ehp.98106719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nagao T, Saito Y, Usumi K, Kuwagata M, Imai K. Reproductive function in rats exposed neonatally to bisphenol A and estradiol benzoate. Reprod Toxicol. 1999;13(4):303–311. doi: 10.1016/s0890-6238(99)00017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rasier G, Toppari J, Parent AS, Bourguignon JP. Female sexual maturation and reproduction after prepubertal exposure to estrogens and endocrine disrupting chemicals: a review of rodent and human data. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;254–255:187–201. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Betancourt AM, Eltoum IA, Desmond RA, Russo J, Lamartiniere CA. In utero exposure to bisphenol A shifts the window of susceptibility for mammary carcinogenesis in the rat. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(11):1614–1619. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pollack AZ, Buck Louis GM, Chen Z, et al. Bisphenol A, benzophenone-type ultraviolet filters, and phthalates in relation to uterine leiomyoma. Environ Res. 2015;137:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mäkinen N, Mehine M, Tolvanen J, et al. MED12, the mediator complex subunit 12 gene, is mutated at high frequency in uterine leiomyomas. Science. 2011;334(6053):252–255. doi: 10.1126/science.1208930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang H, Shen Q, Ye LH, Ye J. MED12 mutations in human diseases. Protein Cell. 2013;4(9):643–646. doi: 10.1007/s13238-013-3048-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mittal P, Shin YH, Yatsenko SA, Castro CA, Surti U, Rajkovic A. Med12 gain-of-function mutation causes leiomyomas and genomic instability. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(8):3280–3284. doi: 10.1172/JCI81534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang T, Zhang X, Obijuru L, et al. A micro-RNA signature associated with race, tumor size, and target gene activity in human uterine leiomyomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2007;46(4):336–347. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Marsh EE, Lin Z, Yin P, Milad M, Chakravarti D, Bulun SE. Differential expression of microRNA species in human uterine leiomyoma versus normal myometrium. Fertil Steril. 2008;89(6):1771–1776. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.05.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Luo X, Chegini N. The expression and potential regulatory function of microRNAs in the pathogenesis of leiomyoma. Semin Reprod Med. 2008;26(6):500–514. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1096130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Qiang W, Liu Z, Serna VA, et al. Down-regulation of miR-29b is essential for pathogenesis of uterine leiomyoma. Endocrinology. 2014;155(3):663–669. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Crabtree JS, Jelinsky SA, Harris HA, et al. Comparison of human and rat uterine leiomyomata: identification of a dysregulated mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. Cancer Res. 2009;69(15):6171–6178. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kovács KA, Lengyel F, Környei JL, et al. Differential expression of Akt/protein kinase B, Bcl-2 and Bax proteins in human leiomyoma and myometrium. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;87(04/05):233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Karra L, Shushan A, Ben-Meir A, et al. Changes related to phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling in leiomyomas: possible involvement of glycogen synthase kinase 3alpha and cyclin D2 in the pathophysiology. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(8):2646–2651. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.03.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yin XJ, Wang G, Khan-Dawood FS. Requirements of phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase and mammalian target of rapamycin for estrogen-induced proliferation in uterine leiomyoma- and myometrium-derived cell lines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(2):176.e1–176.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Varghese BV, Koohestani F, McWilliams M, et al. Loss of the repressor REST in uterine fibroids promotes aberrant G protein-coupled receptor 10 expression and activates mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(6):2187–2192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215759110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lara PN, Jr, Longmate J, Mack PC, et al. Phase II study of the AKT inhibitor MK-2206 plus erlotinib in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer who previously progressed on erlotinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(19):4321–4326. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Borahay MA, Al-Hendy A, Kilic GS, Boehning D. Signaling pathways in leiomyoma: understanding pathobiology and implications for therapy. Mol Med. 2015;21:242–256. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2014.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kolch W. Meaningful relationships: the regulation of the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway by protein interactions. Biochem J. 2000;351(Pt 2):289–305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gustavsson I, Englund K, Faxén M, Sjöblom P, Lindblom B, Blanck A. Tissue differences but limited sex steroid responsiveness of c-fos and c-jun in human fibroids and myometrium. Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6(1):55–59. doi: 10.1093/molehr/6.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lessl M, Klotzbuecher M, Schoen S, Reles A, Stöckemann K, Fuhrmann U. Comparative messenger ribonucleic acid analysis of immediate early genes and sex steroid receptors in human leiomyoma and healthy myometrium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(8):2596–2600. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.8.4141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yu L, Saile K, Swartz CD, et al. Differential expression of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) and IGF-I pathway activation in human uterine leiomyomas. Mol Med. 2008;14(05/06):264–275. doi: 10.2119/2007-00101.Yu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nierth-Simpson EN, Martin MM, Chiang TC, et al. Human uterine smooth muscle and leiomyoma cells differ in their rapid 17beta-estradiol signaling: implications for proliferation. Endocrinology. 2009;150(5):2436–2445. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ono M, Yin P, Navarro A, et al. Inhibition of canonical WNT signaling attenuates human leiomyoma cell growth. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(5):1441–1449. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mangioni S, Viganò P, Lattuada D, Abbiati A, Vignali M, Di Blasio AM. Overexpression of the Wnt5b gene in leiomyoma cells: implications for a role of the Wnt signaling pathway in the uterine benign tumor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(9):5349–5355. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tanwar PS, Lee HJ, Zhang L, et al. Constitutive activation of Beta-catenin in uterine stroma and smooth muscle leads to the development of mesenchymal tumors in mice. Biol Reprod. 2009;81(3):545–552. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.075648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ciarmela P, Islam MS, Reis FM, et al. Growth factors and myometrium: biological effects in uterine fibroid and possible clinical implications. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17(6):772–790. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Laping NJ, Everitt JI, Frazier KS, et al. Tumor-specific efficacy of transforming growth factor-beta RI inhibition in Eker rats. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(10):3087–3099. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chegini N, Luo X, Ding L, Ripley D. The expression of Smads and transforming growth factor beta receptors in leiomyoma and myometrium and the effect of gonadotropin releasing hormone analogue therapy. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;209(01/02):9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shen Y, Wu Y, Lu Q, Zhang P, Ren M. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling pathway cross-talking with ERalpha signaling pathway on regulating the growth of uterine leiomyoma activated by phenolic environmental estrogens in vitro. Tumour Biol. 2015;23(8):1873–1883. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3813-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Di X, Andrews DM, Tucker CJ, et al. A high concentration of genistein down-regulates activin A, Smad3 and other TGF-β pathway genes in human uterine leiomyoma cells. Exp Mol Med. 2012;44(4):281–292. doi: 10.3858/emm.2012.44.4.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ren Y, Yin H, Tian R, et al. Different effects of epidermal growth factor on smooth muscle cells derived from human myometrium and from leiomyoma. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(4):1015–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Peng L, Wen Y, Han Y, et al. Expression of insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) and IGF signaling: molecular complexity in uterine leiomyomas. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(6):2664–2675. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.10.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Burroughs KD, Howe SR, Okubo Y, Fuchs-Young R, LeRoith D, Walker CL. Dysregulation of IGF-I signaling in uterine leiomyoma. J Endocrinol. 2002;172(1):83–93. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1720083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Swartz CD, Afshari CA, Yu L, Hall KE, Dixon D. Estrogen-induced changes in IGF-I, Myb family and MAP kinase pathway genes in human uterine leiomyoma and normal uterine smooth muscle cell lines. Mol Hum Reprod. 2005;11(6):441–450. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cook JD, Walker CL. The Eker rat: establishing a genetic paradigm linking renal cell carcinoma and uterine leiomyoma. Curr Mol Med. 2004;4(8):813–824. doi: 10.2174/1566524043359656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Arslan AA, Gold LI, Mittal K, et al. Gene expression studies provide clues to the pathogenesis of uterine leiomyoma: new evidence and a systematic review. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(4):852–863. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Everitt JI, Wolf DC, Howe SR, Goldsworthy TL, Walker C. Rodent model of reproductive tract leiomyomata. Clinical and pathological features. Am J Pathol. 1995;146(6):1556–1567. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Prizant H, Sen A, Light A, et al. Uterine-specific loss of Tsc2 leads to myometrial tumors in both the uterus and lungs. Mol Endocrinol. 2013;27(9):1403–1414. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Suo G, Sadarangani A, Lamarca B, Cowan B, Wang JY. Murine xenograft model for human uterine fibroids: an in vivo imaging approach. Reprod Sci. 2009;16(9):827–842. doi: 10.1177/1933719109336615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tsibris JC, Porter KB, Jazayeri A, et al. Human uterine leiomyomata express higher levels of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, retinoid X receptor alpha, and all-trans retinoic acid than myometrium. Cancer Res. 1999;59(22):5737–5744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Cardozo ER, Clark AD, Banks NK, Henne MB, Stegmann BJ, Segars JH. The estimated annual cost of uterine leiomyomata in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(3):211.e1–211.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Nieman LK, Blocker W, Nansel T, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of CDB-2914 treatment for symptomatic uterine fibroids: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase IIb study. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(2):767–72. e1, 2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.09.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Morris EP, Rymer J, Robinson J, Fogelman I. Efficacy of tibolone as “add-back therapy” in conjunction with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue in the treatment of uterine fibroids. Fertil Steril. 2008;89(2):421–428. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Loverro G, Nicolardi V, Selvaggi L. Depot GnRH analog treatment of uterine fibroids. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1993;43(2):199–201. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(93)90333-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]