Abstract

Objective To establish whether an association exists between use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and suicide attempts.

Design Systematic review of randomised controlled trials.

Data sources Medline and the Cochrane Collaboration's register of controlled trials (November 2004) for trials produced by the Cochrane depression, anxiety, and neurosis group.

Selection of studies Studies had to be randomised controlled trials comparing an SSRI with either placebo or an active non-SSRI control. We included clinical trials that evaluated SSRIs for any clinical condition. We excluded abstracts, crossover trials, and all trials whose follow up was less than one week.

Results Seven hundred and two trials met our inclusion criteria. A significant increase in the odds of suicide attempts (odds ratio 2.28, 95% confidence 1.14 to 4.55, number needed to treat to harm 684) was observed for patients receiving SSRIs compared with placebo. An increase in the odds ratio of suicide attempts was also observed in comparing SSRIs with therapeutic interventions other than tricyclic antidepressants (1.94, 1.06 to 3.57, 239). In the pooled analysis of SSRIs versus tricyclic antidepressants, we did not detect a difference in the odds ratio of suicide attempts (0.88, 0.54 to 1.42).

Discussion Our systematic review, which included a total of 87 650 patients, documented an association between suicide attempts and the use of SSRIs. We also observed several major methodological limitations in the published trials. A more accurate estimation of risks of suicide could be garnered from investigators fully disclosing all events.

Introduction

Worldwide, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are prescribed for the treatment of depression and an expanding list of additional conditions. SSRIs rank among the most commonly prescribed medications in the world, in large part because they have been marketed as safe and effective in treating common conditions.1-3 Concerns related to safety were raised in the early 1990s, with reports describing a possible association with suicidality.4-6 However, inferences regarding the plausibility and strength of the association between suicidality and the use of SSRIs have been divergent.7-9 An early meta-analysis showed that SSRIs potentially decreased suicidal ideation as measured by a single question on the Hamilton depression score.7 A more recent review of data from 77 trials submitted to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) found a non-significant increase in suicide rates between patients allocated to SSRIs and those allocated to placebo or other antidepressants.8 Because suicides and suicide attempts are rare events, the inability to document an important difference may be a function of the small number of patients in single studies and meta-analyses published to date. Nevertheless, the UK Committee on Safety of Medicines and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have issued public health advisories concerning the use of antidepressants and suicidality.10,11

Given the controversy, we undertook a systematic review of all published randomised controlled trials regardless of treatment indication, to evaluate the association between suicide attempts and the use of SSRIs.

Methods

Literature search strategy

We conducted a systematic literature search to identify all randomised controlled trials of SSRIs indexed on Medline between 1967 and June 2003. The search strategy combined the text terms “SSRI”, “serotonin uptake inhibitors”, “fluoxetine”, “Prozac”, “sertraline”, “Zoloft”, “paroxetine”, “Paxil”, “fluvoxamine”, “Luvox”, “Citalopram”, and “Celexa” with the Dickersin filter for randomised controlled trials.12 In addition, we searched the Cochrane Collaboration's register of controlled trials (November 2004) for trials produced by the Cochrane depression, anxiety, and neurosis group with the same strategy. We also reviewed the bibliographies of three systematic reviews13-15 and identified trials to identify relevant reports. Three authors (SD, BH, and DF) independently reviewed all citations retrieved from the electronic search to identify potentially relevant trials. Each citation was reviewed by at least two individuals. When a unanimous decision could not be reached, a third reviewer was consulted to resolve the difference.

Identification of articles and abstraction of data

To be eligible for inclusion, studies had to be randomised controlled trials comparing an SSRI with either placebo or an active non-SSRI control. We included clinical trials that evaluated SSRIs for any clinical condition. We excluded abstracts, crossover trials, and all trials whose follow up was less than one week. Crossover trials were excluded because of the difficulty in appropriately attributing an outcome to treatment and the poor reporting of the relation between adverse events and treatment.

We developed a standardised data abstraction form that included the condition treated, modes of treatment compared, duration of treatment, the number of patients randomly assigned to each treatment group, the number of patients reported to have completed treatment, patients' demographics, and funding sources. Because our primary aim was to evaluate a rare, serious event and not effectiveness of treatment, we did not quantify the quality of individual study reports by using a formal quality scale. We limited eligibility to trials that were truly randomised and examined individual sources of clinical and methodological heterogeneity including clinical indication, trial duration, sex, age, sample size, and dropouts.

Outcomes

The primary outcome, suicide attempts, included both fatal and non-fatal acts of suicide. We documented rates of fatal and nonfatal suicide attempts separately. Fatal suicide attempts were self inflicted acts resulting in death, as reported in the primary studies. We made conservative assumptions to deal with the published reporting of non-fatal suicide attempts. The authors had literally to use the term “suicide.” The one exception was the use of the term “overdose.” If the authors explicitly reported that there were no adverse or serious adverse events, we recorded that there were no fatal or non-fatal suicide attempts. If no suicide attempts were mentioned but the authors accounted for all adverse events and reasons for discontinuation, we recorded zero suicide attempts. Subjects for which the authors did not indicate a reason for withdrawal or discontinuation we did not count as suicide attempts.

Methodological considerations

We documented how adverse events were reported, dropout rates, sample size, and the number of trials that did not report adverse events. To deal with poor reporting of adverse events, we included a “not reported” category. This category comprised trials that did not mention adverse events or reasons for discontinuation of therapy, provided an incomplete listing of all adverse events, or did not explicitly state that no serious adverse events had been observed. We also documented the proportion of trials that chose to report adverse events beyond percentage thresholds (for example, 5%) or occurring in more than a defined number of patients. We determined the proportion of studies with dropout rates exceeding 15% and 25% and reported the size of trials as the proportion of trials with a total number of patients less than 50, between 50 and 100, and exceeding 100.

Analysis

As an initial description of the risk of suicide overall and in major comparisons, we calculated the absolute risk per 1000 patients treated by dividing the number of events (suicide attempts) by individuals exposed to therapies and multiplying by 1000. To account for exposure time, we calculated the number of episodes of suicide attempts per 1000 person years of exposure by assuming a constant risk over the first year and using a weighted average of exposures.

To evaluate the association between suicide attempts and the use of SSRIs, we undertook three separate meta-analyses: SSRIs compared with placebo, with tricyclic antidepressants, and with other active forms of treatment excluding placebo and tricyclic antidepressants. Within each comparison, we tested the association between suicide attempts and the use of SSRIs by calculating odds ratios using fixed effects models. We used Peto's methods to calculate odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.16-18 An odds ratio greater than 1 implies greater risk in the SSRI group, and an odds ratio less than 1 implies greater risk in the non-SSRI group. We conducted separate meta-analyses for the number of fatal and non-fatal suicide attempts. We did not incorporate trials categorised as “not reported” into the analyses.

A priori subgroups of interest were based on age, the duration of the study follow up, proportion of women, and primary diagnosis of participants in the trials (major depression, depression, and other conditions). We examined the reported partial or total funding source (funded by, compared with not funded by, the pharmaceutical industry). We also conducted a cumulative meta-analysis to evaluate the temporal sequence of evidence of effect.

Results

The literature search identified a total of 3717 citations. After initial review by at least two authors (SD, BH, DF), 999 trials were deemed potentially eligible. Of these, we excluded 375 for the following reasons: duplicate publication (n = 125), not a randomised controlled trial (n = 118), SSRI control only (n = 62), no SSRI arm (n = 13), subgroup analysis (n = 20), foreign language other than French or English (n = 13), short trial duration (n = 12), incomplete or inaccessible data (n = 10), and population of suicidal patients (n = 2). We identified an additional 78 trials meeting eligibility criteria by the electronic search of the Cochrane Collaboration register of controlled trials (Cochrane depression, anxiety, and neurosis group) and the manual review of the bibliographies of three published systematic reviews and of all eligible trials (fig 1).13-15 The 702 trials comprised 411 comparisons between SSRIs and placebo, 220 comparisons between SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants, and 159 comparisons between SSRIs and active therapies other than placebos or tricyclic antidepressants. As some trials had more than one comparison arm, the total number of comparisons exceeds the number of published trials. Of the 159 comparisons, the most common comparative treatments were moclobemide (21 trials), psychotherapy (20), maprotiline (18), and mianserin (16).

Fig 1.

Identification and inclusion of trials

Four hundred and thirty seven trials (62.3%) randomised less than 100 patients. Forty nine trials (7.0%) went on for longer than six months. Of the 493 trials that reported dropout information, 227 (46.0%) had a dropout rate of more than 25%. One hundred and four trials (14.8%) reported adverse events beyond thresholds of 3%, 5%, or 10% of enrolled patients or occurring in more than a defined number of patients, without any detail of adverse events related to suicidality.

Of the 702 trials including 87 650 patients, 414 (59.0%) were conducted in patients with a diagnosis other than major depressive conditions. Sixty eight per cent of trials (n = 475) included more than 50% women, and 91% (n = 638) of trials were conducted in participants with an average age of less than 60 years.

A total of 345 trials representing 36 445 patients reported the number of suicide attempts (143 in total) and were included in the analysis. Of the 345 trials reporting suicide attempts as adverse events, 64 reported at least one suicide attempt. In comparing trial characteristics between trials that reported suicide attempts and those that did not, the only significant difference was that larger trials tended not to report (χ2 test, df = 2, P = 0.001). The overall rate of suicide attempts was 3.9 (95% confidence interval 3.3 to 4.6) per 1000 patients treated in clinical trials. When we used study duration as exposure time, we found an incidence of 18.2 suicide attempts per 1000 patient years. For the trials conducted in patients with depression, the overall rate of suicide attempts was 4.9 (95% confidence interval 4.2 to 5.6 per 1000 patients). Table 1 provides the reported numbers of fatal and non-fatal suicide attempts.

Table 1.

Fatal and non-fatal suicide attempts in the analysed trials

| No of trials* | No of patients | No of suicide attempts | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All trials | Trials that report | Fatal | Non-fatal | Total | ||||||||

| All trials | Trials that report | SSRI | Control | SSRI | Control | SSRI | Control | SSRI | Control | SSRI | Control | |

| SSRI v placebo | 411 | 189 | 28 803 | 21 767 | 10 557 | 7856 | 4 | 3 | 23 | 6 | 27 | 9 |

| SSRI v tricyclic antidepressants | 220 | 115 | 12 740 | 11 609 | 6126 | 5401 | 5 | 4 | 29 | 31 | 34 | 35 |

| SSRI v other | 159 | 83 | 8856 | 9059 | 4130 | 4233 | 3 | 5 | 24 | 13 | 27 | 18 |

SSRI=selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Represents the number of comparisons, as some trials had more than one comparison arm.

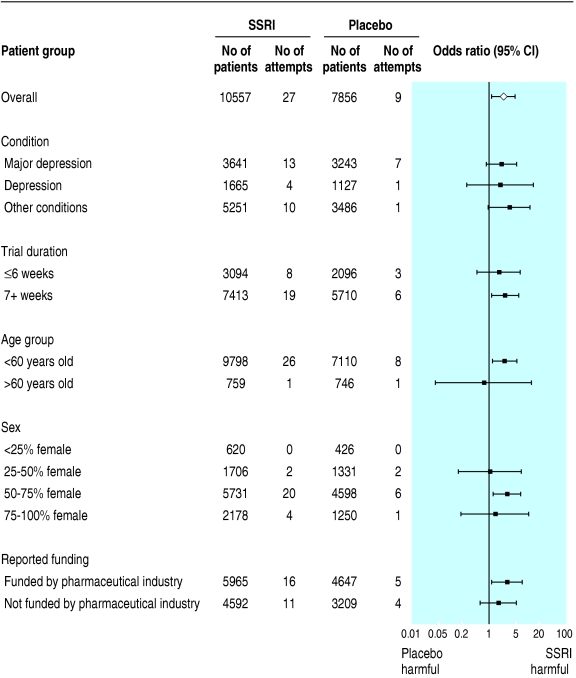

We found a significant increase in the odds of suicide attempts (odds ratio 2.28, 1.14 to 4.55, number needed to treat to harm 684; P = 0.02) for patients receiving SSRIs compared with placebo (fig 2). Given reduced sample sizes, our ability to detect significant differences within subgroups was limited. However, all odds ratios exceeded 1.0 except for trials whose participants had a mean age of over 60 (fig 2). In comparing non-fatal suicide attempts, a significant difference overall remained (2.70, 1.22 to 5.97; P = 0.01). In comparing fatal suicide attempts, we did not detect any differences between SSRIs and placebo (0.95, 0.24 to 3.78).

Fig 2.

Fatal and non-fatal suicide attempts in SSRI trials and placebo trials

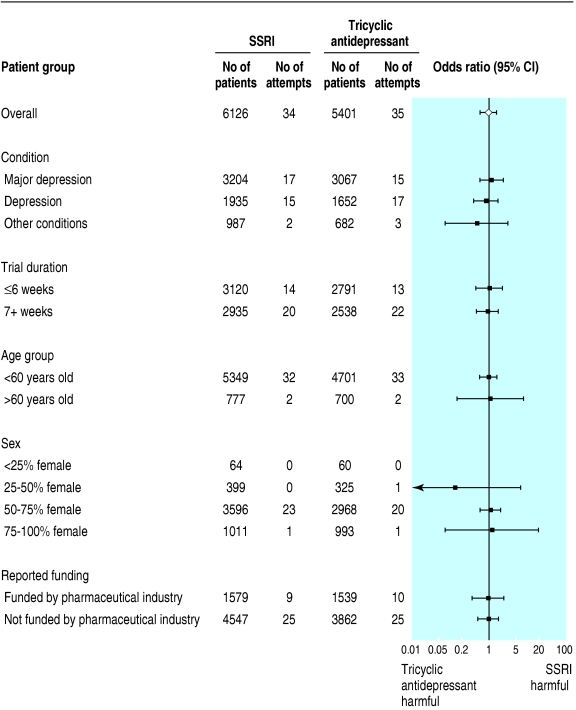

In the pooled analysis of SSRIs compared with tricyclic antidepressants, we did not detect differences in the odds of suicide attempts (0.88, 0.54 to 1.42; fig 3). We found no clinically or statistically important differences in any subgroup analyses. The odds ratio of non-fatal suicide attempts was 0.85 (0.51 to 1.43) and the odds ratio of fatal suicide attempts for SSRIs compared with tricyclic antidepressants was 7.27 (1.26 to 42.03).

Fig 3.

Fatal and non-fatal suicide attempts in SSRI trials and trials studying tricyclic antidepressants

We found an increase in the odds of suicide attempts when comparing SSRIs with therapeutic interventions other than tricyclic antidepressants (1.94, 1.06 to 3.57, number needed to treat to harm 239; fig 4). Again with smaller sample sizes, we found no subgroup specific differences that reached significance. All odds ratios exceeded 1.0, except for trials in which the proportion of women exceeded 75%. The odds ratio for fatal suicide attempts was 0.59 (0.16 to 2.24) and that for non-fatal suicide attempts 2.25 (1.16 to 4.35).

Fig 4.

Fatal and non-fatal suicide attempts in SSRI trials and trials studying other therapies

Discussion

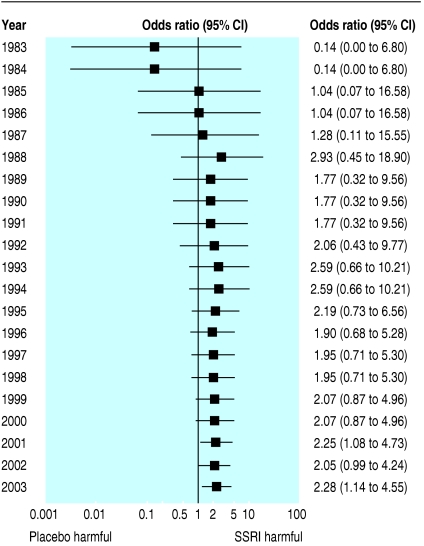

We documented a more than twofold increase in the rate of suicide attempts in patients receiving SSRIs compared with placebo or therapeutic interventions other than tricyclic antidepressants. Although many trials have documented the benefits of SSRIs in many forms of depression and other clinical indications, it has been difficult to document the relatively rare but very serious risk of suicide. We documented a difference in absolute risk of 5.6 suicide attempts per 1000 patient years of SSRI exposure compared with placebo. Although small, the incremental risk remains a very important population health issue because of the widespread use of SSRIs. In the United Kingdom, 1 million person years of SSRI treatment are provided annually by general practitioners.13 For the United States, the number of visits by patients for depression was 24.5 million in 2001, a 70% increase since 1987.1 In 2001, 69% of patient visits for depression resulted in prescriptions for SSRIs.1 Thus, a large number of patients were at risk for treatment induced suicidality. Cumulative metaanalysis reinforces concern with the potential trend towards harm over the past several years (fig 5). It is unclear whether regulatory authorities were aware of this or not.

Fig 5.

Cumulative meta-analysis of fatal and non-fatal suicide attempts in placebo controlled trials

Possible explanations for our findings

In this meta-analysis, the increase in the number of suicide attempts was not associated with a comparable increase in the risks of fatal suicide attempts. Several explanations are plausible. We observed non-significant divergent risks of suicide among different clinical conditions. Estimates for patients with major depression favoured a decrease in suicides with SSRIs, whereas patients with depression and other clinical indications may have as much as an eightfold increase in the rates of suicide, thus resulting in an overall null effect. In all instances, the number of events was too small to generate sufficiently narrow confidence intervals. If the mechanism of action thought responsible for inducing suicidality is true, the agitation and akathasia known to occur with this class of agents may have affected non-depressed and depressed patients differently, inducing more distress in patients with less severe clinical conditions than in those with severe depression. This may account for the greater number of suicide attempts in patients without severe depression. Another explanation could be that these trials do not reflect true practice and that treating more severely depressed patients with a higher inherent risk of suicide in a controlled environment may produce a more favourable ratio of risks to benefits. These explanations would reconcile the observed benefits attributed to SSRIs with the proposed risks associated with the induced agitation that accompanies initiation of treatment, missed doses, decreases of dosage, or discontinuation of treatment. One implication from our findings is that patients with mild illness who are being treated without supervision in the community may require closer monitoring by general practitioners, family, friends, or work colleagues.

A review of published and unpublished sources documented increased rates of suicide in patients with depression when records from the FDA were considered.19 Our review noted suicide attempts at a rate of 3.9 episodes per 1000 patients, whereas suicide attempts documented by Healey approximated 15.3 episodes per 1000 patients treated with SSRIs, a 3.9-fold difference in rates. The difference in rates implies that a substantial proportion of suicide attempts have gone unreported.8,20

Limitations

As additional evidence of difficulties in reporting, we were unable to find documentation confirming or refuting suicide attempts in 51 205 of the 87 650 patients. We conducted a survey of a random sample of 35 (10%) trials that did not report suicide attempts. Of the 17 responders, two reported suicide attempts, seven reported no suicide attempts, and eight confirmed that these data were not collected. Of the two responses that reported suicide attempts, one reported a non-fatal suicide attempt in the SSRI group and none in the placebo group, and the other reported a non-fatal suicide attempt in the SSRI group and two non-fatal attempts in the group taking tricyclic antidepressants. In our random sample of non-responders, 22.2% of trials (n = 2) therefore reported a suicide attempt compared with 18.6% of trials (n = 64) in our entire sample.

Only one trial (0.14%) mentioned a potential association between suicidality or any aspect of self inflicted injuries and SSRIs in their background or discussion sections,21 despite repeated concerns about this adverse effect expressed in scientific discourse.4-6 One hundred and four of the 702 trials reported adverse events that occurred in excess of a prespecified threshold of either 3%, 5%, or 10% of patients or above a certain number of patients (for example, three patients). As a consequence, rare but lethal complications may have gone unreported or under-reported.

In addition to under-reporting, we documented other important limitations. Of 493 trials that reported dropout rates, 28.7% (n = 18 217) of the 63 478 patients dropped out. In most study areas, patients who are lost to follow up tend to be less compliant with treatment, do not derive comparable benefits, and have a greater frequency of adverse outcomes compared with other patients in trials.22 High rates of losses to follow up may therefore have hindered the ability to detect risks of suicide.

Trial size and duration of follow up are obstacles to detecting associations between SSRIs and rare adverse events. Clinical trials have focused largely on symptoms rather than long term outcomes, such as resolution of depression, prevention of relapse, and long term quality of life. As a consequence, 62.3% of trials (n = 437) enrolled fewer than 100 patients, which made rare events difficult to document in individual trials. In a comparable manner, the mean duration of treatment and follow up in published trials was 10.8 weeks with fewer than 6300 (7.0%) patients in 49 (6.6%) trials followed for more than six months. It is therefore impossible to infer rates of long term risks and benefits of treatment, especially in relation to other therapies. At best, we can make assumptions only on the basis of rates of events from short periods of follow up documented in systematic reviews.

Several study manoeuvres were introduced into clinical trials that may alter response to treatment and rates of suicide and suicide attempts. In 29 trials representing 4243 patients, investigators limited trial entry to those patients who were known to respond to and tolerate SSRIs. Restricting eligibility in this manner would effectively diminish adverse events during the conduct of the trial. In addition, some trials enrolled patients receiving SSRIs into a placebo arm without an adequate washout period, thereby potentially attributing adverse events associated with the discontinuation of treatment to the placebo or attributing adverse events to placebo in patients who were successfully treated by SSRIs.

Conclusions

Despite the limitations of the 702 primary reports we synthesised information by using conservative outcome definitions and documented an association between suicide attempts and the use of SSRIs. A more accurate estimation of the risks of suicide would be garnered from investigators fully and accurately disclosing all events. Our review also showed major limitations in the published medical literature. Doctors rely on published reports for their treatment decisions, making open and complete reporting scientifically and ethically essential.

What is already known on this topic

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are a widely prescribed medication

SSRIs are used to treat an expanding list of indications

Divergent studies exist on whether SSRIs are associated with an increase in suicidal events

What this study adds

Evidence from this study supports the association between the use of SSRIs and increased risk of fatal and non-fatal suicide attempts

While the incremental risk is low, the widespread use of SSRIs makes this a population health concern

A number of major methodological limitations of the published trials may have led to an underestimate of the risk of suicide attempts

We thank Michelle Grondin for her help in retrieving articles and abstracting data and Nancy Cleary for her administrative assistance. In addition, we thank all authors and investigators who responded to our survey of the non-reporting trials.

Contributors: DF conceived the study. DF, SD, KG, and SS designed the study. DF and SD collected, managed, and analysed the data. All authors interpreted the data and contributed to the writing of the paper. DF is the guarantor.

Funding: Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Competing interests: DH has had consultancies with, been a principal investigator or clinical trialist for, been a chairman or speaker at international symposia for, or been in receipt of support to attend foreign meetings from: Astra, Astra-Zeneca, Boots/Knoll, Eli Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Lorex-Synthelabo, Lundbeck, Organon, Pharmacia & Upjohn, PierreFabre, Pfizer, Rhone-Poulenc Rorer, Roche, SmithKline Beecham, Solvay, and Zeneca. DH has been an expert witness for the plaintiff in eight legalactions involving SSRIs and has been consulted on several cases of attempted suicide, suicide, and suicide-homicide after antidepressant medication, in most of which he has offered the view that the treatment was not involved. He has also been an expert witness for the defendants (the British NHS) in a large series of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) cases.

References

- 1.Stafford RS, MacDonald EA, Finkelstein SN. National patterns of medication treatment for depression, 1987 to 2001. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2001;3: 232-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vanderhoff BT, Miller KE. Major depression: assessing the role of new antidepressants. Am Fam Physician 1997;55: 249-54, 259-60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guze BH, Gitlin M. New antidepressants and the treatment of depression. J Fam Pract 1994;38: 49-57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teicher MH, Glod C, Cole JO. Emergence of intense suicidal preoccupation during fluoxetine treatment. Am J Psychiatry 1990;147: 207-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rothschild AJ, Locke CA. Reexposure to fluoxetine after serious suicide attempts by three patients: the role of akathisia. J Clin Psychiatry 1991;52: 491-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masand P, Gupta S, Dewan M. Suicidal ideation related to fluoxetine treatment. N Engl J Med 1991;324: 420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baldwin D, Bullock T, Montgomery D, Montgomery S. 5-HT reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants and suicidal behaviour. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1991;6(suppl 3): 49-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan A, Khan S, Kolts R, Brown WA. Suicide rates in clinical trials of SSRIs, other antidepressants, and placebo: analysis of FDA reports. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160: 790-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jick H, Kaye JA, Jick SS. Antidepressants and the risk of suicidal behaviours. JAMA 2004;292: 338-43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, United States Food and Drug Administration. Worsening depression and suicidality in patients being treated with antidepressant medications. www.fda.gov/cder/drug/antidepressants/AntidepressanstPHA.htm (accessed 11 May 2004).

- 11.Committee on Safety of Medicines, Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, United Kingdom. Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in children and adolescents with major depressive disorder (MDD)—only fluoxetine (Prozac) shown to have a favourable balance of risks and benefits for the treatment of MDD in the under 18s. http://medicines.mhra.gov.uk/ourwork/monitorsafequalmed/safetymessages/cemssri_101203.pdf (accessed 30 June 2004).

- 12.Dickersin K, Scherer R, Lefebvre C. Systematic reviews: Identifying relevant studies for systematic reviews. BMJ 1994;309: 1286-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.North of England Evidence Based Guideline Development Project. Evidence based clinical practice guideline: the choice of anti-depressants for depression in primary care. Report 91. Newcastle upon Tyne: Centre for Health Services Research, 1998.

- 14.Barbui C, Hotopf M, Freemantle N, Boynton J, Churchill R, Eccles MP, et al. Treatment discontinuation with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) versus tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(4): CD002791. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Geddes JR, Freemantle N, Mason J, Eccles MP, Boynton J. SSRIs versus other antidepressants for depressive disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2): CD001851. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Alderson P, Green S, Higgins JPT, eds. Cochrane reviewers' handbook 4.2.2 [updated December 2003]. Cochrane Library, Issue 1, 2004. Chichester, UK: John Wiley.

- 17.Deeks J, Bradburn M, Bilker W, Localio R, Berlin J. Much ado about nothing: statistical methods for meta-analysis with rare events. Proceedings of the Sixth Cochrane Colloquium, Baltimore, USA, 1998: 50.

- 18.Sweeting MJ, Sutton AJ, Lambert PC. What to add to nothing? Use and avoidance of continuity corrections in meta-analysis of rare events. 4th Symposium on Systematic Reviews: Pushing the Boundaries. Oxford, July 2002

- 19.Healy D, Whitaker C. Antidepressants and suicide: risk-benefit conundrums. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2003;28: 331-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whittington CJ, Kendall T, Fonagy P, Cottrell D, Cotgrove A, Boddington E. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in childhood depression: systematic review of published versus unpublished data. Lancet 2004;363: 1341-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steiner M, Steinberg S, Stewart D, Carter D, Berger C, Reid R, et al. Fluoxetine in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoria. Canadian Fluoxetine/Premenstrual Dysphoria Collaborative Study Group. N Engl J Med 1995. 8;332: 1529-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haynes RB, Dantes R. Patient compliance and the conduct and interpretation of therapeutic trials. Control Clin Trials 1987;8: 12-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]