A number of genes are periodically transcribed during cell cycle progression. How the periodic transcription patterns of these genes are achieved is not completely understood. Cyclin C, a component of Mediator, plays an essential role in periodic transcription and the timing of cell cycle progression.

Abstract

The multiprotein Mediator complex is required for the regulated transcription of nearly all RNA polymerase II–dependent genes. Mediator contains the Cdk8 regulatory subcomplex, which directs periodic transcription and influences cell cycle progression in fission yeast. Here we investigate the role of CycC, the cognate cyclin partner of Cdk8, in cell cycle control. Previous reports suggested that CycC interacts with other cellular Cdks, but a fusion of CycC to Cdk8 reported here did not cause any obvious cell cycle phenotypes. We find that Cdk8 and CycC interactions are stabilized within the Mediator complex and the activity of Cdk8-CycC is regulated by other Mediator components. Analysis of a mutant yeast strain reveals that CycC, together with Cdk8, primarily affects M-phase progression but mutations that release Cdk8 from CycC control also affect timing of entry into S phase.

INTRODUCTION

A large number of genes are periodically transcribed during cell cycle progression in eukaryotic cells. These genes often encode cyclins—transcription factors and protein kinases with roles in normal cell cycle progression. The observed gene expression patterns are required for normal growth and may be perturbed in cancer cells (Wittenberg and Reed, 2005; Haase and Wittenberg, 2014). In fission yeast, ∼87 genes (denoted cluster 1) are activated at mitosis and repressed in G1 of the next cell cycle (Rustici et al., 2004), and periodic control of their transcription is linked to quantitative changes in cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1) activity (Banyai et al., 2016). Transcription of a subset of these genes is regulated by two forkhead transcription factors, Sep1 and Fkh2, which have opposing effects on cluster 1 expression. Whereas loss of Sep1 causes reduced transcription of mitotic genes, loss of Fkh2 elevates M-phase transcription levels. Further underscoring this Yin and Yang relationship, Sep1 is found associated with cluster 1 promoters during gene activation, whereas Fkh2 associates with repressed promoters (McInerny, 2011).

The multiprotein Mediator complex is a coregulator of RNA polymerase II (Pol II) transcription (Carlsten et al., 2013). Mediator forms a physical bridge that transduces regulatory information from gene-specific transcription factors (activators and repressors) to the Pol II transcription machinery as it assembles on the promoter (Conaway and Conaway, 2011). Mediator stimulates basal transcription, supports activated transcription, and enhances TFIIH-dependent phosphorylation of the C-terminal domain of Pol II (Myers et al., 1998; Björklund and Gustafsson, 2005; Esnault et al., 2008).

In fission yeast, Mediator consists of a core complex of 15 subunits, which can associate with a four-component Cdk8 module containing Med12, Med13, Cdk8, and cyclin C (CycC) to form a larger form of Mediator (L-Mediator). Whereas core Mediator can bind Pol II, Mediator associated with the Cdk8 module is always isolated in the free form, devoid of Pol II (Samuelsen et al., 2003; Elmlund et al., 2006; Bourbon, 2008). The Cdk8 module is targeted by a number of different intracellular signaling pathways, and the kinase activity has been shown to phosphorylate different molecular targets involved in transcription regulation (Szilagyi and Gustafsson, 2013). In contrast to the situation in many other eukaryotes, the conserved Med15 protein is not a stable component of fission yeast Mediator. Instead, Med15 forms a complex with Hrp1, a CHD1 ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling protein. The Med15–Hrp1 complex can associate with L-Mediator, and the subcomplex plays a role in the regulated transcription of some fission yeast genes (Khorosjutina et al., 2010).

In previous work, we demonstrated that Cdk8 is required for correct timing of mitotic entry in fission yeast (Szilagyi et al., 2012). The kinase phosphorylates Fkh2 in a cell cycle–dependent manner, which in turn prevents proteolysis and leads to oscillation of cellular Fkh2 levels. Inactivation of the Cdk8 kinase activity or mutation of the Fkh2 phosphorylation sites leads to delayed mitotic entry. In contrast, replacement of the targeted Fkh2 serine residues with glutamic acid—a mutation that mimics phosphorylation—causes premature mitotic entry. How Cdk8 is regulated is not well understood, but other Mediator components appear to influence its activities. Cdk8 is anchored to Mediator via Med12 and Med13, and loss of these anchoring proteins causes premature phosphorylation of Fkh2 and, as a consequence, early entry into mitosis (Banyai et al., 2014). In contrast to other Cdks, Cdk8 is not activated by T-loop phosphorylation because its putative T-loop lacks a phosphoacceptor site. In addition, the concentration of its cognate cyclin, CycC, does not change during cell cycle progression (Leopold and O’Farrell, 1991). Instead, CycC forms a stable complex with Med12, Med13, and Cdk8 (Borggrefe et al., 2002). The molecular mechanisms leading to temporal activation of Cdk8 remain unclear.

In contrast to Cdk8, a requirement for CycC for timing of M-phase progression has not been demonstrated. The cyclin was first identified in a search for mammalian and Drosophila genes that could rescue a yeast strain lacking G1 cyclins (Leopold and O’Farrell, 1991). A physiological role for CycC in G1 regulation, however, has been difficult to demonstrate. CycC contains a conserved surface groove, which forms interactions with the N-terminus of Med12. Oncogenic mutations in this region of Med12 uncouple CycC and Cdk8 from the core Mediator complex, leading to a reduction in CycC-dependent kinase activity (Turunen et al., 2014).

Here we address the importance of CycC for M-phase progression in fission yeast. Our data support direct interactions between Med12 and CycC and suggest that the Cdk8–CycC interaction is stabilized within the Mediator complex. We find that CycC is required for correct timing of mitosis. Finally, we use a fusion between Cdk8 and CycC to study how Cdk8–CycC affects cell cycle progression outside the context of Mediator.

RESULTS

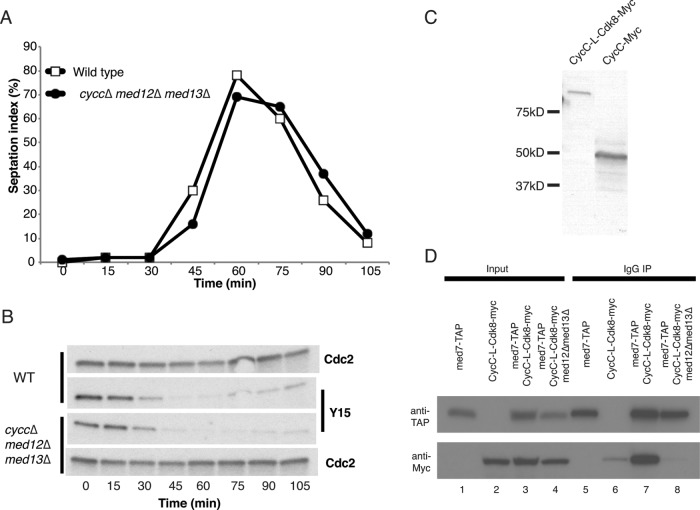

CycC interacts with L-Mediator independently of Cdk8

We first characterized interactions between CycC and the Mediator. To this end, we used strains expressing TAP-tagged Med7 or CycC (Figure 1). With TAP-Med7, we could isolate a mixture of L-Mediator and core Mediator in complex with Pol II, whereas TAP-CycC allowed us to isolate L-Mediator devoid of Pol II from a wild-type yeast background (Figure 1, lane 2). We also isolated TAP-CycC from med12, Δmed13, and Δcdk8 cells. TAP-CycC protein isolated from Δmed12 and Δmed13 did not associate with other Mediator components tested (Figure 1, lanes 3–5), demonstrating that Med12 and Med13 are required for stable interactions between CycC and the Mediator complex. We observed no Cdk8 associated with the free TAP-CycC, suggesting that the Cdk8–CycC pair is unstable outside the context of the Mediator. Of interest, when purified from Δcdk8 cells, some TAP-CycC remained associated with Mediator, demonstrating that CycC can interact with Mediator even in the absence of its kinase partner (Figure 1, lane 4).

FIGURE 1:

CycC interacts with L-Mediator independently of Cdk8. Mediator complexes were purified with TAP-Med7 or TAP-CycC. Purified complexes were separated on 12% SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies directed against the proteins indicated.

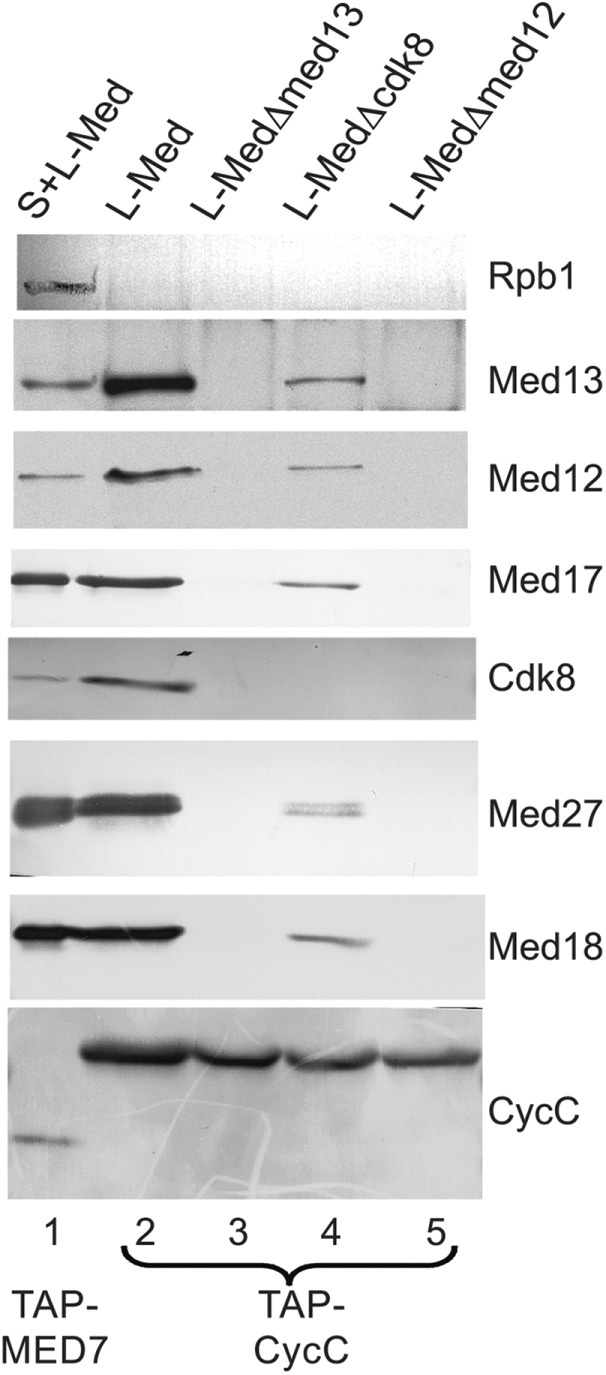

CycC binds to the mitotic ace2 promoter

To investigate whether CycC associates in a periodic manner with mitotic promoters, we synchronized cells by cdc25-22 block release and analyzed Myc-tagged CycC recruitment by time-resolved chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis. At 36°C (nonpermissive temperature), the cdc25-22 mutation arrests cells in G2, which allows synchronized entry into mitosis when the cells are shifted back to 25°C (permissive temperature). We analyzed protein binding with quantitative real-time PCR and found that CycC interacted with the mitotic ace2 promoter in a periodic manner. The peak of binding (Figure 2) coincided with the peak of core Mediator recruitment to the same promoter (Med7-myc in Figure 2). We can therefore conclude that CycC is recruited together with Mediator to mitotic promoters.

FIGURE 2:

Cyclin C binds to the mitotic ace2 promoter together with the Mediator complex. Time-resolved ChIP of C-terminally tagged CycC-Myc and Med7-Myc proteins. Samples were collected at the indicated time points.

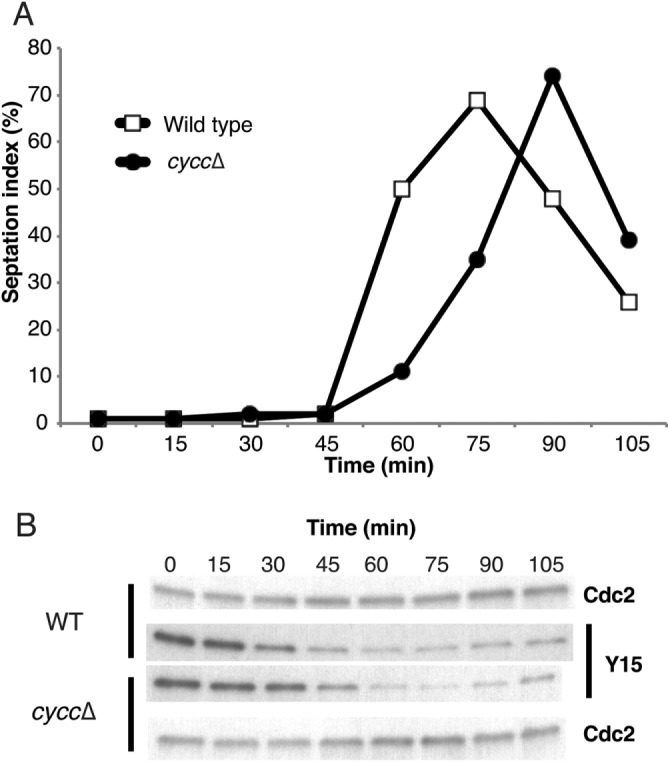

Deletion of cycc delays mitotic entry

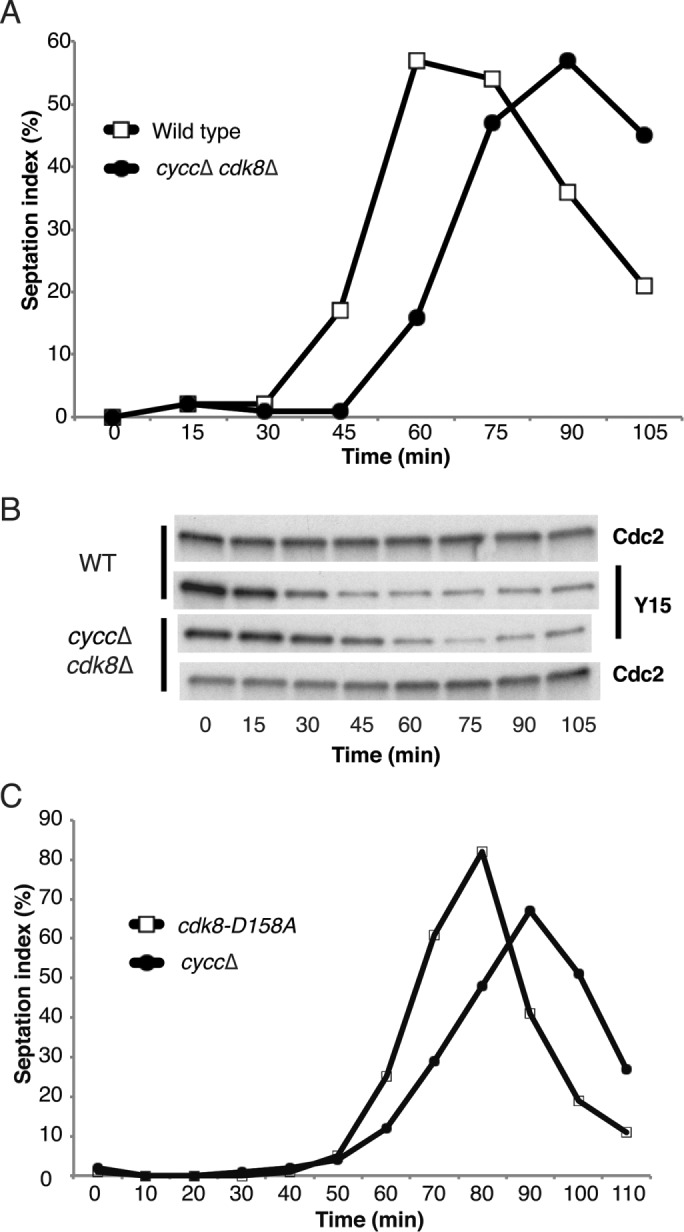

Next we investigated whether loss of CycC affects cell cycle progression. Using cells synchronized by cdc25-22 block release, we compared septation indices for wild-type and cyccΔ cells. The mutant cells displayed delayed septation (Figure 3A). We also analyzed the phosphorylation status of Tyr-15 on Cdk1 (the product of the cdc2+ gene in fission yeast), which is a key event during mitotic entry. Cdk1–Tyr-15 dephosphorylation was delayed ∼15 min in cyccΔ mutant cells compared with a wild-type (wt) control (Figure 3B). The observed delay in cell cycle progression in cyccΔ cells was similar to what we observed in cdk8-D158A kinase mutant (Szilagyi et al., 2012) and cdk8Δ cells (unpublished data). Our data thus indicated that Cdk8 and CycC act in concert to promote cell cycle progression. In support of this notion, we observed no additive effects when both cdk8 and cycc were deleted. The cdk8Δ/cyccΔ mutant displayed a delay in cell septation and Cdk1–Tyr-15 dephosphorylation (Figure 4, A and B) similar to what we observed in cyccΔ, cdk8Δ, and cdk8-D158A cells (Szilagyi et al., 2012), suggesting that they affect cell cycle progression via the same genetic pathway. In fact, a direct comparison revealed that the delay in septation was even more pronounced in cyccΔ than in cdk8-D158A kinase mutant cells (Figure 4C).

FIGURE 3:

Cyclin C can regulate cell cycle progression. Deletion of the cycc gene results in (A) delayed septation and (B) delayed Cdc2-Tyr15 dephosphorylation.

FIGURE 4:

Cyclin C and Cdk8 regulate cell cycle progression in the same genetic pathway. A cdk8 cycC double-deletion strain displays delayed septation (A) and delayed Cdc2–Tyr-15 dephosphorylation (B) similar to the single mutations (Figure 3). (C) The delay in septation is more pronounced in cyccΔ than in cdk8-D158A cells.

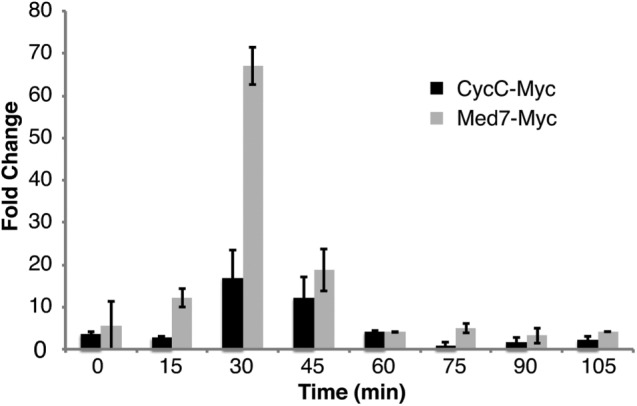

A CycC–L-Cdk8 fusion protein and its effect on cell cycle progression

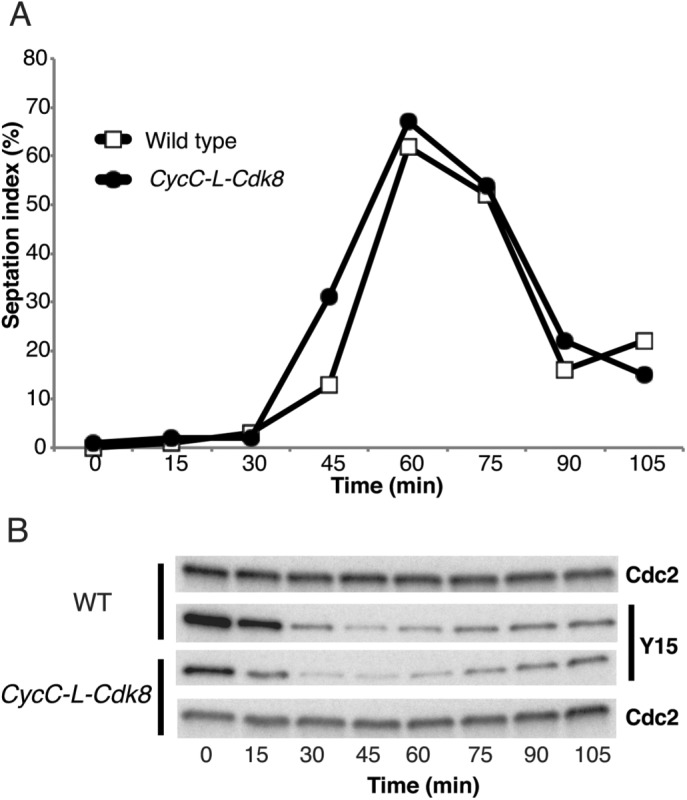

Our data suggested that CycC together with Cdk8 controls mitotic entry and that the interaction between these two proteins is stabilized within the context of the Mediator. We previously showed that deletion of med12+ and med13+ can suppress the effects of cdk8Δ on cell cycle progression (Banyai et al., 2014). We now observed that deletion of med12+ and med13+ also suppressed the effects of cyccΔ on septation and Tyr-15 dephosphorylation (Figure 5, A and B). The basis for the observed suppression is not clear, but we know that Cdk8 forms an active free pool when released from the Mediator by deletion of both med12+ and med13+ (Banyai et al., 2014). On the basis of our biochemical characterization of L-Mediator (Figure 1), we cannot exclude that deletion of med12+ and/or med13+ also leads to the formation of a free pool of CycC, raising the intriguing possibility that free Cdk8 or CycC may associate with other cyclins or Cdks and thereby affect cell cycle progression. To address this possibility, we restricted CycC interactions to Cdk8 by physically fusing the two proteins in vivo. The fusion gene, which also encoded 13-mer Myc-tag at the C-terminus, was used to replace the endogenous cycc+ gene. We also deleted cdk8+ in the strain expressing CycC–L-Cdk8, so that only one copy of the cdk8+ gene would be present in the genome. We verified that the fusion protein was expressed as a full-length protein by immunoblot analysis (Figure 5C). To ensure that the CycC–L-Cdk8 fusion protein could be incorporated into the Mediator, we used TAP-tagged Med7 to pull down Mediator complexes from wt and mutant strains using immunoglobulin G (IgG) beads (Figure 5D). The CycC–L-Cdk8 fusion protein was associated with other Mediator components, and, as expected, it was lost in the med12Δ med13Δ mutant background. We also analyzed the timing of septation and Cdk1 Tyr-15 dephosphorylation and found that the CycC-L–Cdk8 fusion strain behaved like the wt control (Figure 6, A and B).

FIGURE 5:

A CycC–L-Cdk8 fusion protein can associate with Mediator. The timing of (A) septation and (B) Cdc2-Tyr15 dephosphorylation is similar between a wt and a cyccΔ med12Δ med13Δ mutant strain. (C) The CycC–L-Cdk8 fusion protein (Myc-tagged) is expressed and migrates at the expected molecular weight. (D) CycC–L-Cdk8 associates with Mediator in wt cells (lane 7) but not in med12Δ med13Δ mutant cells (lane 8).

FIGURE 6:

The CycC–L-Cdk8 fusion protein is active and does not affect cell cycle progression. CycC–L-Cdk8 fusion protein in cdk8Δ background shows normal (A) septation timing and (B) Cdc2–Tyr-15 dephosphorylation.

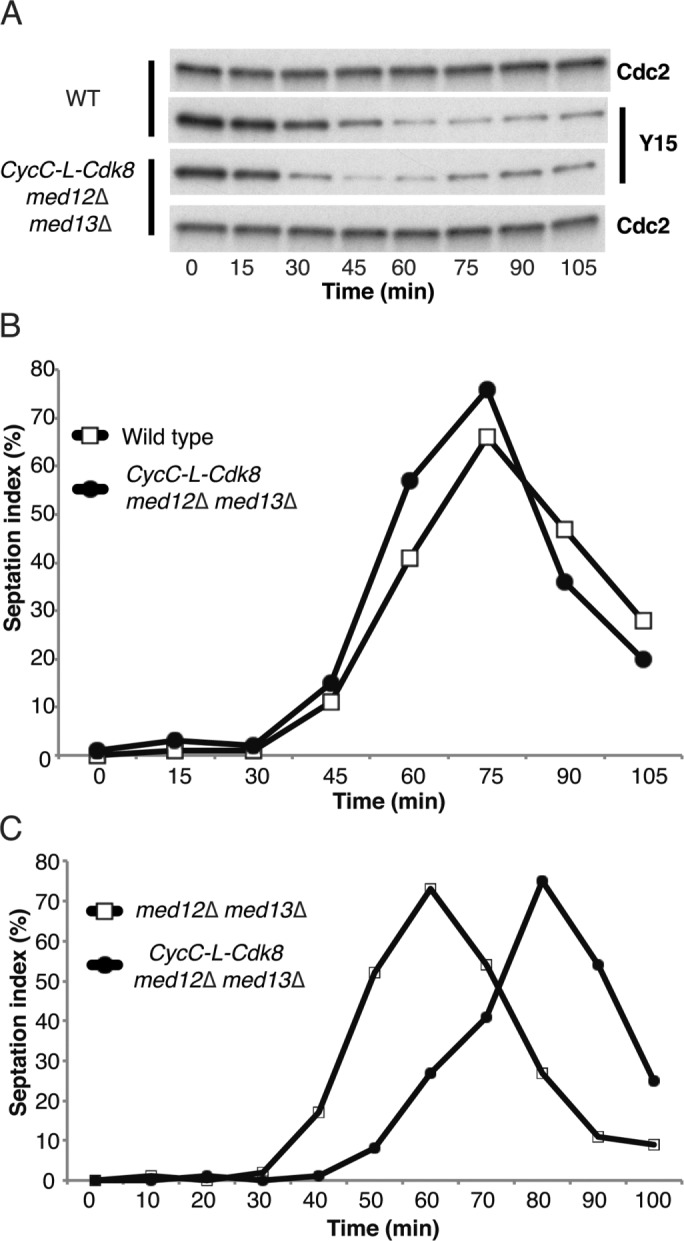

We next investigated how deletion of med12+ and med13+ affected the timing of mitotic entry in the CycC–L-Cdk8 fusion strain. We found that med12Δmed13Δ still resulted in early mitotic entry, as judged by Cdk1 Tyr-15 dephosphorylation (Figure 7A). Therefore the observed effect on mitotic progression cannot be explained by interactions between Cdk8 and/or CycC with other cyclins or Cdks. In contrast, the fusion between CycC and Cdk8 prevented the early septation observed in med12Δmed13Δ cells. Timing of septation was similar between wt and med12Δ med13Δ CycC-L-Cdk8 cells (Figure 7B). A direct comparison demonstrated that septation was ∼20 min earlier in med12Δ med13Δ than in med12Δ med13Δ CycC-L-Cdk8 cells (Figure 7C).

FIGURE 7:

The CycC–L-Cdk8 fusion restores wt timing of septation in med12Δ med13Δ cells. CycC–L-Cdk8 fusion in med12Δ med13Δ background leads to (A) early dephosphorylation of Cdc2–Tyr-15 as compared with wt. The timing of septation in CycC-L-Cdk8 med12Δ med13Δ cells is similar to wt (B) and ∼20 min later than observed in med12Δ med13Δ cells (C).

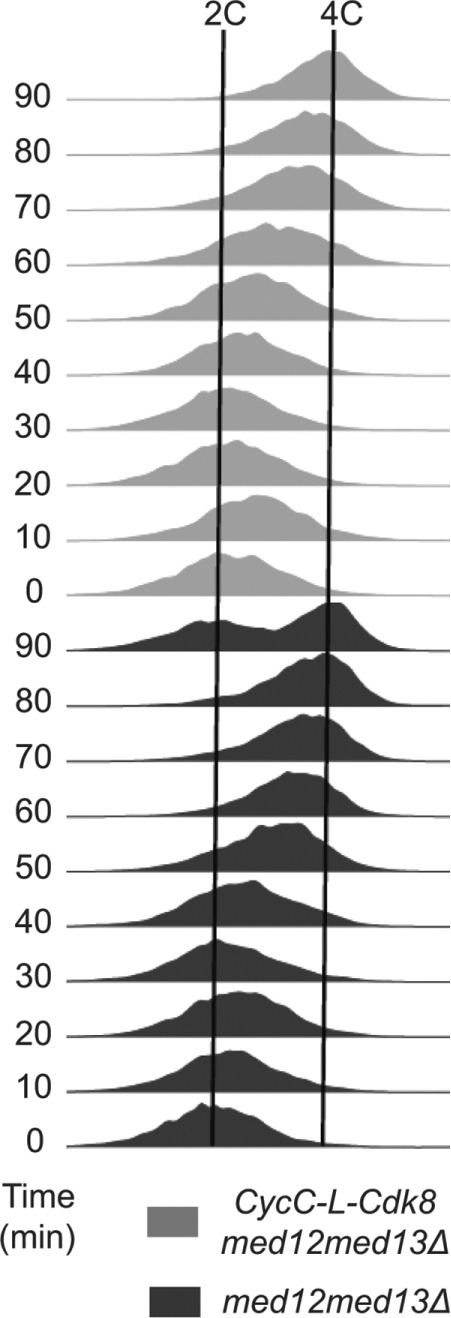

Septation coincides with S phase in synchronously dividing cells (Rustici et al, 2004). We therefore followed up the septation observations using flow cytometry analysis to monitor the timing of DNA synthesis. We compared S-phase entry in synchronously dividing med12Δ med13Δ cells with S-phase entry in med12Δmed13Δ cells expressing the CycC–L-Cdk8 fusion construct. This analysis revealed that S phase was earlier in med12Δmed13Δ than in med12Δ med13Δ CycC-L-Cdk8 cells (Figure 8). On the basis of these observations, we conclude that a CycC–L-Cdk8 fusion counteracts the early S-phase entry caused by med12Δ med13Δ. It is possible that the fusion prevents CycC and Cdk8 from interacting with other S phase–promoting cyclins and Cdks outside the context of the Mediator complex.

FIGURE 8:

The CycC–L-Cdk8 fusion restores wt timing of S-phase entry in med12Δmed13Δ cells. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis shows that CycC-L-Cdk8 med12Δ med13Δ cells do not display the early S-phase entry observed in med12Δmed13Δ cells.

DISCUSSION

In contrast to other cyclins involved in cell cycle progression, CycC does not oscillate. Instead, Cdk8/CycC activity appears to be regulated by other Mediator subunits. In line with a model previously suggested by others and us, we believe that Med12 and Med13 keep the Cdk8/CycC pair in a repressed state, which can be released when activators and/or signaling pathways induce structural changes in the Mediator complex (Szilagyi and Gustafsson, 2013). Loss of Med12 and/or Med13 may abolish this repressive effect, which explains the early entry into mitosis observed in med12Δ and med13Δ cells. In fact, loss of Med12 and Med13 leads to the release of CycC and Cdk8 from Mediator. We reasoned that a free pool of CycC and Cdk8 might affect cell cycle progression by interacting with alternative cyclins and Cdks. In support of this idea, a previous study of human CycC showed that the protein can interact with an alternative Cdk, namely CDK3 (Ren and Rollins, 2004). To address this possibility experimentally, here we fused CycC to Cdk8, thereby restricting interaction to the cognate partner and analyzed the effects of med12+ and med13+ deletion on cell cycle progression. As demonstrated here, the effects of med12Δmed13Δ on mitotic progression are identical in the Cdk8–L-CycC strain to the effects observed in wt cells, strongly suggesting that Cdk8 and CycC act in concert to regulate timing of mitosis. Loss of Med12 and Med13 also causes early entry into S phase. Of interest, this effect is not observed in CycC–L-Cdk8 cells. The data suggest that eliminating the possibility for Cdk8 and CycC to interact with alternative cyclins and Cdks can restrict the effects of med12+ and med13+ deletions on cell cycle progression. Both overproduction of Cdk8 and mutations in CycC are observed in human tumors. It is tempting to speculate that these mutagenic changes may cause the formation of a free Cdk8 pool in mammalian cells, which could result in spontaneous interactions with alternative cyclins and promote S-phase progression. Limited information is available on the role of Cdk8 and CycC in M-phase progression in mammalian cells. We hope that our findings will stimulate others to elucidate whether the effects we observe in fission yeast are also conserved in higher organisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, media, and genetic methods

Standard molecular biology and molecular genetics methods were used (Moreno et al., 1991). Table 1 lists the strains used in this study. Primer sequences and conditions are available upon request. Cell culturing was performed using yeast extract liquid (YEL) or yeast extract agar supplemented with Geneticin (G418) or nourseothricin if required. Cells were grown at 25°C unless otherwise stated.

TABLE 1.

: Yeast strains used in this study.

| Strain | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| CG-8 | med7+::TAP kanMX6 ade6-216 h- | This study |

| CG-15 | cdc25-22 h+ | M. Sipiczki (University of Debrecen) |

| CG-550 | CycC::13myc-NATMX6 cdc25-22 h+ | This study |

| CG-45 | cdc25-22 med7+::myc-kanMX6 h- | Szilagyi et al. (2012) |

| CG-43 | cdk8::ura4+ ura4-D18 h+ | This study |

| CG-406 | h− med12::natMX4 med13::kanMX4 cdc25-22 | Banyai et al. (2014) |

| CG-559 | CyCC:kanMX4 med13::kanMX4 med12::nat-MX4 cdc25-22 h+ | This study |

| CG-536 | CycC::kanMX4 cdc25-22 h+ | This study |

| CG-565 | CycC::kanMX4 cdk8::ura4+ cdc25-22 h+ | This study |

| CG-574 | CycC-L-Cdk8-13myc-NATMX6 cdk8::ura4+ cdc25-22 h- | This study |

| CG-575 | CycC-L-Cdk8-13myc-NATMX6 cdk8::ura4+ med13::kanMX4 med12::nat-MX4 cdc25-22 h- | This study |

| CG-589 | CycC-L-Cdk8-13myc-NATMX6 med7::TAP-kanMX6 cdk8::ura4+ h- | This study |

| CG-595 | CycC-L-Cdk8-13myc-NATMX6 cdc25-22 med7::TAP-kanMX6 med13::kanMX4 med12::nat-MX4 cdk8::ura4+ h+ | This study |

| TP42 | h+ ade6-M210 med7+-CTAP::G418R | Samuelsen et al. (2003) |

| CGP101 | h- spCycC+-CTAP::G418R | This study |

| CGPV105 | h- Δmed12:: G418R _cycC+-CTAP::natMX | This study |

| CGPV106 | h- Δmed13::G418 R _ cycC+-CTAP::natMX | This study |

| CGPV107 | h+ cdk8::ura4+_cycC+-CTAP::natMX | This study |

C-terminally tagged CycC mutants were created using the pFA6-13myc-NATMX6 plasmid (Van Driessche et al., 2005). PCR fragments were amplified from wild-type genomic DNA and cloned into PvuII-PacI and SacI-EcoRV sites. The amplified plasmid was then digested by PvuII and EcoRV enzymes and transformed into wild-type cells using the protocol described in Van Driessche et al. (2005). The resulting colonies were then analyzed by PCR and immunoblotting.

CycC and Cdk8 were fused together via a linker region with the amino acid sequence GGGGSGGGGSGGGGS. The fused protein (CycC–L-Cdk8) was C-terminally tagged with a 13× Myc-tag. Briefly, cDNAs of the two genes and the linker sequence were amplified by standard PCR (KOD Hot Start DNA polymerase, 71086; Merck) and then fused together by overlap extension PCR. The resulting DNA fragment was cloned into the SalI, PacI site of the pFA6-13myc-NATMX6 plasmid. Sequences 500 base pairs long upstream and downstream of the wild-type cycc open reading frame were amplified by PCR and then fused together with the Myc-tagged CycC–L-Cdk8 construct by overlap extension PCR using the Expand Long Template PCR system (11681834001; Roche). The linear DNA was used to transform cdk8Δ cells following a previously described protocol (Van Driessche et al., 2005). Resulting colonies were analyzed by PCR, DNA sequencing, and immunoblotting.

Protein methods and purification

For purification of TAP-tagged Mediator, 15 l of yeast cell culture was grown to OD600 = 3.0–4.0 in YES (0.5% yeast extract, 3.0% glucose, 0.0225% adenine, 0.0225% histidine, 0.0225% leucine, 0.0225% uracil, and 0.0225% lysine) medium supplemented with 0.2 g/l adenine according to Spahr et al. (2001). Briefly, cells were collected by centrifugation (2500 rpm for 7 min at 4°C; JA-10, Beckman Coulter), washed once with ice-cold water, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Cells were broken in a Freezer/Mill 6850 (SPEX CertiPrep, NJ) using the following program: 10 min precooling and seven cycles with 2 min of beating and 2 min of rest at stringency 14. Broken cells were suspended in 0.5 ml of buffer A (200 mM KOH–4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid, pH 7.8, 15 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 15% glycerol, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], and protease inhibitors) per gram of cell pellet. After the supernatant was cleared by centrifugation (at 9000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C; JA-10), one-ninth volume of 2 M KCl was added and stirred for 15 min. After ultracentrifugation (at 42,000 rpm for 20 min at +4°C; Ti45, Beckman Coulter), 500 µl of IgG beads (1 ml of slurry; Amersham Biosciences) was added and incubated for 1 h at 4°C. IgG beads were collected by centrifugation (at 1000 rpm for 2 min at 4°C; JA-17, Beckman Coulter), loaded into a column, and washed with 30 ml of IgG buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM KOAc, or 150 mM NaCl, pH 8.0). After washing with 20 ml of tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavage buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.05% NP-40, pH 8.0), Mediator was eluted by incubation for 1 h at 16°C with 200 U of TEV protease in 2 ml of TEV buffer.

Immunoblot analysis for Med17, Med18, and Med27 was performed as described in Spahr et al. (2001). Recombinant Schizosaccharomyces pombe Cdk8 (amino acids [aa] 2–293), CycC (full length), and Med12 (aa 957–1148) and Med13 (aa 1–209) proteins fused to glutathione S-transferase (GST) was overproduced in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) pLysS cells (Stratagene) and purified from inclusion bodies as described (Cairns et al., 1994). The purified GST-Cdk8, GST-CycC, and GST-Med12 were used to immunize rabbits, and GST-Med13 was used to immunize chicken (AgriSera, Vännäs, Sweden). Antibodies to detect the c-Myc tag (9E10) and pol II (8WG16) were both from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Whole-cell extracts were produced from (1–4) × 108 nonsynchronous or synchronous cultures grown in YEL medium. Cells were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and immediately frozen at −20 or −80°C until further processing. Cells were lysed using a FastPrep machine for five cycles of 20 s of beating and 2 min of rest. We used the previously described lysis buffer for our experiments (Szilagyi et al., 2012). CycC–Cdk8 fusion was detected by anti-Myc antibody (1:1000; M4439, Sigma-Aldrich). CoIP of the fusion protein was performed by adding 60 µl of IgG beads to the total cell extract and slowly rotating at 4°C. The beads were then washed with lysis buffer three times, eluted by 1× SDS loading buffer, and heated to 95°C for 5 min. Peroxidase–antiperoxidase antibody (1:1000; P1291, Sigma-Aldrich) was used for detection of the TAP-Med7 protein. The antibodies and their concentrations were previously described (Szilagyi et al., 2012; Banyai et al., 2014).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

ChIP experiments were performed as described previously (Szilagyi et al., 2012). The ChIP DNA was analyzed with the Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-time PCR machine. All ChIP experiments were done at least twice and with two parallel IP repeats in each experiment. At least two PCR repeats were performed with all DNA samples. Fold change was calculated by comparing IP samples to no-antibody controls. Error bars indicate SD between IP repeats. For each cell cycle synchronization experiment, septation index was determined from counting at least 100 cells at each given time point.

Imaging methods

Native cell images for septation index experiments were taken with an Olympus CX41 microscope equipped with a DP70 camera.

Flow cytometry

Approximately 107 cells were harvested for each time point, resuspended in 70% ethanol, and stored at 4°C until use. Flow cytometry measurement was performed using a BD FACSAria cell sorting system and the propidium iodide staining method (www-bcf.usc.edu/~forsburg/yeast-flow-cytometry.html). Data analysis was done by using FlowJo (www.flowjo.com) cell cytometry software.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ulf Yrlid (University of Gothenburg) for help with flow cytometry experiments. We also thank Camilla Samuelsen and Steen Holmberg (University of Copenhagen) for providing yeast strains. Research was supported by Swedish Research Council Grant 2012-2583, Swedish Cancer Foundation CAN 2013/855, European Research Council Grant 268897, the IngaBritt and Arne Lundberg Foundation, and the Knut and Alice Wallenbergs Foundation.

Abbreviations used:

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- Pol II

RNA polymerase II

- wt

wild type.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBoC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E16-11-0787) on May 17, 2017.

REFERENCES

- Banyai G, Baidi F, Coudreuse D, Szilagyi Z. Cdk1 activity acts as a quantitative platform for coordinating cell cycle progression with periodic transcription. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11161. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyai G, Lopez M, Szilagyi Z, Gustafsson C. Mediator can regulate mitotic entry and direct periodic transcription in fission yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34:4008–4018. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00819-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björklund S, Gustafsson C. The yeast mediator complex and its regulation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:240–244. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borggrefe T, Davis R, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Kornberg R. A complex of the Srb8, -9, -10, and -11 transcriptional regulatory proteins from yeast. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44202–44207. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207195200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourbon H. Comparative genomics supports a deep evolutionary origin for the large, four-module transcriptional mediator complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:3993–4008. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns B, Kim Y, Sayre M, Laurent B, Kornberg R. A multisubunit complex containing the SWI1/ADR6, SWI2/SNF2, SWI3, SNF5, and SNF6 gene products isolated from yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1950–1954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsten J, Zhu X, Gustafsson C. The multitalented mediator complex. Trends Biochem Sci. 2013;38:531–537. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conaway R, Conaway J. Function and regulation of the mediator complex. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2011;21:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmlund H, Baraznenok V, Lindahl M, Samuelsen C, Koeck P, Holmberg S, Hebert H, Gustafsson C. The cyclin-dependent kinase 8 module sterically blocks mediator interactions with RNA polymerase II. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15788–15793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607483103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esnault C, Ghavi-Helm Y, Brun S, Soutourina J, Van Berkum N, Boschiero C, Holstege F, Werner M. Mediator-dependent recruitment of TFIIH modules in preinitiation complex. Mol Cell. 2008;31:337–346. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase S, Wittenberg C. Topology and control of the cell-cycle-regulated transcriptional circuitry. Genetics. 2014;196:65–90. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.152595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khorosjutina O, Wanrooij P, Walfridsson J, Szilagyi Z, Zhu X, Baraznenok V, Ekwall K, Gustafsson C. A chromatin-remodeling protein is a component of fission yeast mediator. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:29729–29737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.153858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leopold P, O’Farrell P. An evolutionarily conserved cyclin homolog from Drosophila rescues yeast deficient in G1 cyclins. Cell. 1991;66:1207–1216. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90043-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInerny C. Cell cycle regulated gene expression in yeasts. Adv Genet. 2011;73:51–85. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-380860-8.00002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno S, Klar A, Nurse P. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:795–823. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94059-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers L, Gustafsson C, Bushnell D, Lui M, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Kornberg R. The Med proteins of yeast and their function through the RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain. Genes Dev. 1998;12:45–54. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren S, Rollins B. Cyclin C/cdk3 promotes Rb-dependent G0 exit. Cell. 2004;117:239–251. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00300-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustici G, Mata J, Kivinen K, Lio P, Penkett C, Burns G, Hayles J, Brazma A, Nurse P, Bahler J. Periodic gene expression program of the fission yeast cell cycle. Nat Genet. 2004;36:809–817. doi: 10.1038/ng1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelsen C, Baraznenok V, Khorosjutina O, Spahr H, Kieselbach T, Holmberg S, Gustafsson C. TRAP230/ARC240 and TRAP240/ARC250 mediator subunits are functionally conserved through evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6422–6427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1030497100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spahr H, Samuelsen C, Baraznenok V, Ernest I, Huylebroeck D, Remacle J, Samuelsson T, Kieselbach T, Holmberg S, Gustafsson C. Analysis of Schizosaccharomyces pombe mediator reveals a set of essential subunits conserved between yeast and metazoan cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:11985–11990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211253898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szilagyi Z, Banyai G, Lopez M, McInerny C, Gustafsson C. Cyclin-dependent kinase 8 regulates mitotic commitment in fission yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:2099–2109. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06316-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szilagyi Z, Gustafsson C. Emerging roles of Cdk8 in cell cycle control. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1829:916–920. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turunen M, Spaeth J, Keskitalo S, Park M, Kivioja T, Clark A, Makinen N, Gao F, Palin K, Nurkkala H, et al. Uterine leiomyoma-linked MED12 mutations disrupt mediator-associated CDK activity. Cell Rep. 2014;7:654–660. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Driessche B, Tafforeau L, Hentges P, Carr A, Vandenhaute J. Additional vectors for PCR-based gene tagging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe using nourseothricin resistance. Yeast. 2005;22:1061–1068. doi: 10.1002/yea.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittenberg C, Reed S. Cell cycle-dependent transcription in yeast: promoters, transcription factors, and transcriptomes. Oncogene. 2005;24:2746–2755. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]