John Hunter (1728-93), surgeon of St George's Hospital, was a brilliant observer, naturalist, and thinker, as well as being an innovative doctor. His philosophy of surgery and his teachings were based on his close observation of his patients, both in life and after death, and on a truly amazing study of the whole field of biology, from the artificial fertilisation of moths' eggs to dissection of the whale. He proudly claimed to pay little attention to the writings of his contemporaries or his predecessors. Although he cannot be said to have made a particular major advance in surgery, his fresh approach to the subject entitles him to be regarded as the father of scientific surgery in the United Kingdom.

Figure 1.

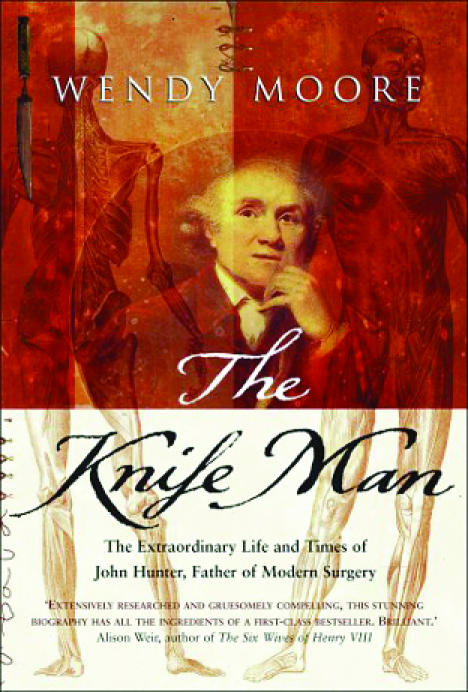

Wendy Moore

Bantam Press, £18.99, pp 482 ISBN 0593 052099

Rating: ★★★

Hunter's life is a biographer's dream. Born a farmer's son in a village outside Glasgow, he was slow in learning to read and write, disliked school, and preferred to wander through the countryside observing nature. At the age of 20, having failed to find any vocation, he joined his brother William, 10 years his senior, who had already established himself in London as a teacher of anatomy and a highly successful obstetrician—he was to deliver the children of Queen Charlotte, wife of George III. Here John proved to be a brilliant dissector and investigator. He studied surgery under Cheselden and Pott, became a student and then house surgeon at St George's, had three years' experience of war surgery on active service during the Seven Years War, and, in 1768, was appointed to the staff of St George's.

The range of his interests is staggering. He studied transplantation of tissues in animals and transplanted teeth in man—indeed, he wrote the first major monograph on the teeth. He carried out artificial insemination, elucidated the exact nature of the placental circulation by careful injection studies (including that of a woman and her child who died at term), pioneered controlled clinical trials by showing that pills made of bread were as “effective” as the conventional remedies of his day in the treatment of gonorrhoea, studied collateral circulation after vascular ligation, and described the operation of ligation of the femoral artery in the subsartorial (Hunter's) canal for popliteal aneurysm. He made important discoveries in the growth of bone, the descent of the testis (he described and named the gubernaculum), and wrote an extensive monograph on gunshot wounds. He was the first to describe the haematogenous spread of cancer, and his specimen of a sarcoma of the femur with secondaries in the thorax can be seen to this day in the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons of England.

But over and above these studies, he founded a school of scientific surgery, including among his disciples Henry Cline, John Abernethy, and, perhaps above them all, Astley Cooper. Edward Jenner was a pupil and became a lifelong friend. It was to Jenner that Hunter wrote the advice “But why think? Why not try the experiment?” which perhaps sums up his philosophy.

Hunter's lectures were like no others at the time. Not for him lists of anatomical facts or standard descriptions of surgical operations. His teaching ranged over the whole range of the “animal oeconomy.” He discussed the differences between living and inanimate matter, the physiology of the organs of the body and how this was disturbed by disease. His lectures were difficult to follow—many students dropped out—but part of the problem was that Hunter had to search for a new vocabulary to discuss these new and controversial topics. We need to remember that he was struggling to explain these phenomena in the days before effective microscopes, before the bacterial causes of wound infections and “fevers” had been discovered, and a century before Darwinism.

It is no wonder that this remarkable man should have had more books and articles written about him than any other British surgeon apart from Joseph Lister (with whom he shares the distinction of having the only public statues erected in their memories in the United Kingdom). Indeed, the first biography of Hunter, admittedly a scurrilous attack upon him, was written by Jesse Foote the year after Hunter's death.

Wendy Moore, a writer and journalist, is to be congratulated on this latest account of the life and times of John Hunter. As a good journalist, she makes excellent use of her material. She describes with gusto the unpleasant sights and smells of the 18th century dissecting rooms, with their putrefying body parts; the midnight forays of the “resurrection men” as they expertly reopened fresh graves and hauled out the corpses by means of a rope around the neck. She describes the agonies of surgery in those pre-anaesthetic days and the crude attempts to cure unpleasant diseases whose causes were still being explained by humoral theories dating back to the times of Galen. She has done her homework well; she has chosen her illustrations with care and her extensive research is demonstrated by her reference list and her 60 pages of notes on the text. She has produced an easy to read account of the life of this remarkable man which, although presumably designed with a lay audience in mind, will be read with pleasure by the professionals.

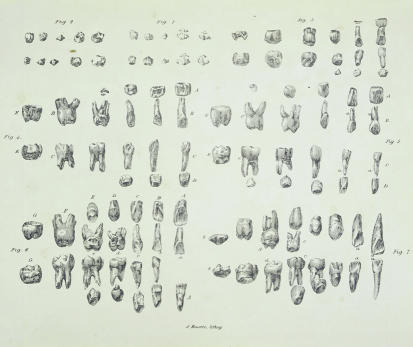

Figure 2.

Hunter's many achievements included the first major monograph on teeth

Credit: WELLCOME INSTITUTE

Here and there we can debate some of her conclusions. Hunter was interested in whether gonorrhoea and syphilis were two separate diseases or, as was commonly believed, were the early and later manifestations of the same infection. He investigated this in 1767 by inoculating “venereal matter from a gonorrhoea” into two puncture wounds on the glans and on the prepuce. The subject developed, firstly, the typical gleet of gonorrhoea, then went on to produce a chancre and then the manifestations of secondary syphilis. Of course, we now surmise that the donor must have had both conditions. These experiments are fully described in Hunter's monograph Treatise on Venereal Disease.

In 1925 Sir D'Arcy Power, in his Hunterian oration entitled “John Hunter, a Martyr to Science,” alleged that the subject of Hunter's experiment was Hunter himself and that he subsequently died from syphilitic disease of the arterial system. Wendy Moore, like many others, goes along with this hypothesis. However, the late George Qvist, in his biography of Hunter published in 1981, argues, I believe quite convincingly, that Power's opinion was “completely erroneous and irresponsible.” Hunter certainly used himself on many occasions as an experimental model, and his writings abound with the use of the personal pronoun in these studies. However, his venereal inoculation experiments are described in an impersonal manner and, moreover, there are other references in his works to deliberate inoculation of patients with venereal matter. Furthermore, the detailed account of the autopsy performed on Hunter by his brother in law, Everard Home, describes the classical appearances of arteriosclerotic disease with calcification of the coronary arteries and with no evidence of the late manifestations of syphilis.