Abstract

Specific phobias (SPs) are characterized by excessive fear or anxiety regarding an object or situation. SPs often result in a host of negative outcomes in childhood and beyond. Children with SPs are broadly assumed to show dispositional over-regulation and fearfulness relative to children without SPs, but there are few attempts to distinguish dispositional patterns among children with SPs. In the present study, we examined trajectories of differing temperamental profiles for youth receiving a CBT-based treatment for their SP. Participants were 117 treatment seeking youth (M Age = 8.77 years, Age Range = 6 – 15 years; 54.7% girls) who met criteria for a SP and their mothers. Three temperament profiles emerged and were conceptually similar to previously supported profiles: well-adjusted; inhibited; and under-controlled. While all groups showed similarly robust reductions in SP severity following treatment, differences among the three groups emerged in terms of broader internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms, and global outlook. The well-adjusted group was higher in functioning initially than the other two groups. The inhibited group had initial disadvantages in initial internalizing symptoms. The under-controlled group showed greatest comorbidity risks and had initial disadvantages in both internalizing and externalizing symptoms. These distinct clusters represent considerable heterogeneity within a clinical sample of youth with SP who are often assumed to have homogenous behavior tendencies of inhibition and fearfulness. Findings suggest that considering patterns of temperament among children with phobias could assist treatment planning and inform ongoing refinements to improve treatment response.

Keywords: Specific Phobias, Temperament, Children and Adolescents, Person-Level Analysis, Growth Models

Specific Phobias among Youth

Specific phobias (SPs) are the most common anxiety disorders (ADs) in children and adolescents (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013; Merikangas et al., 2010). These disorders are often characterized by marked and unreasonable fear or anxiety concerning a specific object or situation (APA, 2013). Hallmark characteristics of SPs include behavioral avoidance as well as physiological hyperarousal and distorted cognitions when in the presence of the feared stimulus. SPs are categorized into five major subtypes: natural environment; blood-injection-injury; animal; situational; and other. Furthermore, SPs serve as risk factors for the development of later anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders (Kagan & Snidman, 1999; Kendall, Safford, Flannery-Schroeder, & Webb, 2004) and often result in academic and social difficulties (Essau, Conradt, & Petermann, 2000; Ollendick, King, & Muris, 2004). Currently, one-session treatment (OST) - a single session therapy based on cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) - is regarded as a rapid and effective intervention to treat youth with SPs across these subtypes (Ollendick & Davis, 2013). These treatments have shown a 50 – 70% response rate in various studies (Ollendick et al., 2009; 2015; Silverman et al., 1999). Although such findings suggest OST is an efficacious treatment approach, they also indicate that a substantial number of youth do not fully respond and that additional factors may be important to achieve a full treatment response.

Given the high prevalence of SPs during development and the implications of SPs for daily functioning and later adjustment, it is timely to consider factors that may increase or buffer risks of SP among youth and their subsequent treatment. Here, we suggest that temperament and patterns of temperamental response are promising candidates to further understand clinical outcomes for children receiving treatment for SPs.

Temperament

There is general agreement that temperament is an important factor in better understanding normal development as well as the multiple forms of psychopathology that might result (Calkins & Fox, 2002; Lonigan & Phillips, 2001; Muris & Ollendick, 2005; Nigg, 2006; Vervoort et al., 2011). Temperament involves patterns of behavioral tendencies with biological underpinnings and children’s attempts to regulate these tendencies given their environmental surroundings (see Goldsmith et al., 1987). These individual differences involve relatively persistent patterns of regulation and reactivity (Kagan & Snidman, 1999; Kagan, Snidman, Kahn, & Towsley, 2007; Rothbart & Bates, 2006; Vervoort et al., 2011).

Extant findings support multiple temperament dimensions (e.g., Thomas & Chess, 1977). Of current interest, Rothbart and colleagues (Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey, & Fisher, 2001; Rothbart & Bates, 2006) have shown support for nine temperament dimensions pertinent to childhood, with three underlying latent factors labeled effortful control (higher attention control, inhibitory control, and sensitivity to perceptual cues), negative affectivity (higher frustration, anger, and depressive mood), and surgency (i.e., higher pleasure-seeking; limited fear; limited shyness). These temperamental factors may provide further nuance in understanding SPs, as these factors have been linked to increased risks for internalizing problems among community children when surgency is lower but effortful control and negative affectivity are higher (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2001; Oldehinkel, Hartman, De Winter, Veenstra, & Ormel, 2004).

Temperament and anxiety disorders

Variable-centered analyses—considering whether specific temperament factors robustly predict child outcomes—indicate that negative affectivity predicts increased risks for internalizing symptoms, whereas effortful control appears to buffer children from these internalizing symptoms (Vervoort et al., 2011). Similarly, Festen and colleagues (2013) showed that children seeking treatment for anxiety disorders were more responsive when they were reported to have higher initial manifestations of surgency. Person-centered patterns of temperament—considering the ways groups of children with different dispositional patterns across multiple temperament factors vary in outcomes—have also shown implications for child psychopathology. McClowry (2002) used temperamental factors of activity control, negative reactivity, task persistence, and approach/withdrawal among community children and found that groups of children in this sample met well-adjusted and challenging profiles of temperament. Challenging profiles included high maintenance children who were highly active and higher in negative affectivity and slow to warmup children who were lower in activity, higher in avoidance, and higher in negative affectivity. Boys disproportionately met the high maintenance pattern, whereas girls disproportionately met the slow to warmup pattern. Similar patterns of concern were found by Eisenberg and colleagues (2001) and labeled as under-controlled (low attentional control, low inhibitory control, high impulsivity) and over-controlled (low attentional control, high inhibitory control, low impulsivity). Children who were diagnosed with internalizing disorders were more likely to show over-controlled patterns of adjustment than under-controlled or well-adjusted patterns.

Further, Caspi and colleagues (Caspi, Henry, McGee, Moffitt, & Silva, 1995; Caspi et al., 2003; Caspi & Silva, 1995) matched temperament patterns from young children with ongoing personality profiles in adulthood. Variable-centered analyses found that effortful control and low surgency at age five was associated with more fear and anxiety across later childhood and adolescence (Caspi et al., 1995). Person-centered analyses found support for five temperament groups (i.e., Under-Controlled, Inhibited, Confident, Reserved, Well-Adjusted) based on observed behaviors at age three and factors of negative affectivity, surgency, and positive affectivity. These factors predicted personality at age 18 (e.g., inhibited individuals were reported minimal impulsivity, danger seeking, and social confidence; Caspi & Silva, 1995) and age 26 (e.g., inhibited individuals reported minimal extraversion; Caspi et al., 2003). We were interested in building on these past efforts to clarify the implications of temperamental patterns on longitudinal, clinical adjustment in a treatment-seeking sample of children with SPs. Within a sample of children seeking treatment for phobias, we expected broad patterns to emerge resembling archetypes of well-adjusted, inhibited, and under-controlled temperament.

The need to address temperament among children with SPs

Given heterogeneity across the childhood anxiety disorders (Higa-McMillan, Smith, Chorpita, & Hayashi, 2008; Rapee & Coplan, 2010), we argue that current research regarding patterns and implications of temperament across other ADs might not readily generalize to SPs. Despite the considerable literature base on temperament influences within ADs, few studies have examined specific patterns of temperament in youth with SP or how patterns of temperament may promote or hinder treatment and clinical outcomes in such youth. Understanding these patterns might clarify an important contributor to different patterns of treatment response for SP (Festen et al., 2013; Ollendick & Davis, 2013). Although OST is an effective treatment for SPs, as noted earlier, a subset of children with SPs do not respond to OST. As such, research addressing possible impeding factors is imperative.

The Present Study

The current study addresses children’s patterns across three temperamental factors: negative affectivity; effortful control; and surgency. We were interested in the ways groups of children who show particular patterns of temperament would also show different trajectories of clinical response following treatment for SPs. While all of the children entered the study with a clinically severe phobia, we aimed to differentiate multiple patterns of temperament within the sample, akin to patterns conceptualized and supported in previous studies by Caspi and Silva (1995) and early on by Thomas and Chess (1977). We also sought to examine how temperament patterns predicted longitudinal trends in clinician- and mother-reported treatment outcomes. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine temperamental profiles specific to youth with SPs and their relations to treatment outcomes. Our first aim was to test whether temperament patterns, akin to patterns previously supported in community samples (Caspi et al., 2003; Caspi & Silva, 1995), would emerge within a sample of youth with an SP. Our second aim was to determine whether temperamental patterns would predict differing outcomes for children in line with previous findings for other ADs.

We expected archetypes that would vary in levels of effortful control, negative affect and surgency which we labeled well-adjusted, behaviorally inhibited, and under-controlled. Children with relatively well-adjusted manifestations of temperament (i.e., higher levels of surgency and effortful control along with lower levels of negative affectivity) were expected to show less severe initial internalizing and externalizing symptoms, as well as SP severity. These children were also expected to show better global functioning and the strongest improvements in these areas over time. Children with inhibited manifestations (i.e., lower surgency, moderate effortful control, and moderate negative affect) were expected to show most severe phobia symptoms and be least responsive to improvements in phobia severity and general internalizing symptoms. Children with under-controlled manifestations (i.e., moderate surgency, lower effortful control, and higher negative affect) were expected to show more severe internalizing and externalizing symptoms and poorer improvement in externalizing symptoms.

Method

Participants

Families seeking treatment for children with SPs were recruited into a randomized clinical control trial (RCT), which examined the relative effectiveness of the standard child-focused one session treatment (OST) and an augmented one-session exposure treatment (A-OST; Ollendick et al., 2015) for children and adolescents with SPs (n = 125; M Age = 8.86 years, Age Range = 6 – 15 years; 52.8% girls). To be eligible to participate, participants had to meet the following criteria: between 6–15 years of age; DSM-IV criteria for a SP (APA, 1994); the SP needed to cause significant interference or distress in the child’s life and be clinical in nature, as established by the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV- Child and Parent Version (ADIS-IV-C/P; Silverman & Albano, 1996); the duration of the phobia needed to be at least 6 months; and the participant was required to discontinue other forms of treatment and be stable on medications for the duration of the RCT. Phobia subtypes included situational (41.4%), environmental (17.6%), animal (38.4%), and other (2.4%). Youth with blood-injection-injury (BII) phobias were specifically excluded from this RCT due to qualitative differences which exist between the BII and other major subtypes (Oar, Farrell, Waters, & Ollendick, 2016). Exclusion criteria for the study also included a primary diagnosis of major depression with suicide intent, pervasive developmental disorder, drug or alcohol abuse, and/or psychosis. A majority of children were European American (84%), 11 children were African American (8.8%), one child was Asian (0.8%), one child was Latino (0.8%), and three children were multiracial (2.4%). All diagnoses were assigned based on criteria outlined by the ADIS-IV-C/P (Silverman & Albano, 1996). Fifty-one children (40.8%) had a comorbid anxiety diagnosis (i.e., generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder), 34 (27.2%) had a comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), 14 (11.2%) had comorbid oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and 2 (1.6%) had comorbid major depressive disorder. SP was the reason for referral in all cases.

Procedure

The study was approved by the institutional review board for human subject research. Participants were recruited through university-affiliated clinics, print advertisements, school health services, pediatricians, and child psychiatric services. Upon initial contact, potential participants’ parents completed a brief phone screener to determine eligibility. Following the phone screen, eligible families were asked to participate in a pre-assessment session. All parents provided informed written consent and all children provided informed assent during the start of the pre-assessment. During the pre-assessment, parents and children completed a clinical intake which consisted of a semi-structured diagnostic interview (see below). Parents and children also completed questionnaires, some of which were not analyzed in the present study. After the assessment, eligibility and diagnoses were determined during a consensus meeting with the parent and child clinicians as well as the project’s doctoral-level clinical supervisor. Subsequent assessment sessions were conducted 1 week, 1 month, and 6 months following treatment. At all of the follow-up assessment sessions, the diagnostic modules endorsed at pre-treatment as well as a battery of questionnaires were administered (see Ollendick et al., 2015, for further details).

Treatments

The child focused OST treatment condition was based on the guiding principles established by Öst (1989, 1997) for adults and subsequently adapted for the treatment of SPs in youth (Ollendick et al., 2009). OST consisted of a three-hour treatment session with the child alone and with limited parent involvement. Within the three-hour session, therapist engaged the child in gradual in-vivo exposure with the primary aim being to challenge and correct distorted beliefs associated with the phobic object or situation. The A-OST treatment condition included the primary caregiver throughout treatment. Following the principles of the child focused OST, the clinician assigned to work with the child engaged the child in gradual in-vivo exposures and challenged the child’s distorted cognitions. The parent observed the treatment session with a second clinician. The second clinician coached the parent on how to conduct exposures and how to reduce reinforcement of avoidance behaviors. Differences between the child focused OST and the augmented OST were not observed (see Ollendick et al., 2015, for details). Consequently, data were combined across the two treatment conditions for purposes of this study.

Measures

The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV-Child and Parent Versions (ADIS-IV-C/P; Silverman & Albano, 1996)

Diagnoses were assigned using the ADIS-IV-C/P, a semi-structured clinical interview that assesses a range of DSM-IV disorders. Separate clinicians administered the ADIS-C and ADIS-P to the child and parent, respectively. During both the ADIS-P and ADIS-C interviews, clinicians assessed the severity of the child’s SP and other potential psychological problems. The two clinicians independently assigned severity ratings (CSR) on a 9-point scale, with a rating of ≥ 4 signifying a clinical level of interference and a diagnosis of the endorsed disorder. ADIS-IV interviews were administered at pre-treatment as well as at all subsequent assessments following treatment. Reliability for the primary and secondary diagnoses was conducted for 25% of the interviews. Reliability values were fair to acceptable (.48 to .96), as reported in Ollendick et al. (2015). Following all assessment sessions, consensus meetings were held where the parent and child clinicians, as well as the project director, discussed the outcomes of both interviews and assigned consensus diagnoses and CSRs. Consensus agreement of the child’s SP CSR at each time point was the primary dependent measure of treatment outcome.

Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS; Shaffer et al., 1983)

The CGAS served as an index of children’s overall functioning. Scores range from 0–100 with higher scores indicating better global functioning. The CGAS has been described as a reliable and valid tool to capture broader functioning in both clinical research and practice (Bird, Canino, Rubio-Stipec, & Ribera, 1987; Green, Shirk, Hanze, & Wanstrath, 1994). For the present study, clinicians used all available information, including ADIS diagnoses, to assign the CGAS rating at all time points.

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991; Achenbach, Dumenci, & Rescorla, 2003)

The CBCL is a standardized, parent-report measure which assesses children’s behavioral and emotional functioning. Using a 3-point scale, parents rated agreement with 113 items concerning their child’s behavior (ranging from 0 = not true to 2 = very true or often true). The CBCL is normed for children ages 6–18 years of age. The present study focuses on two composite scales: Externalizing Problems and Internalizing Problems. Internalizing Problems included Withdrawn, Anxious/Depressed, and Somatic Complaints whereas Externalizing Problems included Rule-Breaking Behavior and Aggressive Behavior. Higher t-scores indicate greater impairment. The CBCL was obtained at pre-treatment, 1-month follow-up, and 6-month follow-up. Internal consistencies were acceptable across time points for internalizing (internal consistency = .82 – .83) and externalizing (internal consistency = .82 – .87) symptom reports.

Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire-Revised (EATQ-R; Ellis & Rothbart, 2001; Putnam, Ellis, & Rothbart, 2001)

The EATQ-R is a parent-report rating scale designed to assess temperament factors related to affectivity, self-regulation, and reactivity. Parents report on 62 items with responses ranging on a 5-point scale (1 = Almost always untrue; 5 = Almost always true). The EATQ-R has been found to be a reliable index of temperament (Ellis & Rothbart, 2001) and has previously been used with school-age samples of children from age 6 onward (e.g., De Pauw & Mervielde, 2011; van Brakel & Muris, 2006). Factor analyses by Ellis and Rothbart (2001) yielded support for three superscales pertinent to childhood as indicated above: a surgency superscale consisting of high intensity pleasure, fear (reverse-scored), and shyness (reverse-scored); an effortful control superscale consisting of attention, inhibitory control, and activation control; and a negative affectivity superscale with frustration, depressive mood, and aggression. Mothers’ reports at pre-treatment were used for all youth in the sample. While the EATQ-R is most often used in reports for children nine years and older, internal consistencies for the superscales were comparable across younger (6 – 8 years) and older (9 and older) children (.81 – .92 for younger children; 79 – .91 for older children) in the current sample.

Data Analyses

Preliminary analyses

Missing data at post-treatment time points were imputed. Five data sets were formed, and the average scores were used for a final data set for analyses. Bivariate correlations were tested among study variables. A k-means cluster analysis was then tested to determine support for three temperament groups.

Hypothesis tests

Hierarchical linear models tested two growth models on reports from mothers (internalizing symptoms and externalizing symptoms) and clinicians (Phobia CSR and CGAS). Time was scored in approximate months since the baseline assessment (0 for baseline; 0.5 for the one-week follow-up to treatment; 1.5 for the one-month follow-up to treatment; and 6.5 for the six-month follow-up to treatment). A preliminary model tested the influence of age, gender, and comorbid status (Anxiety, ODD, ADHD) on the overall intercept. Significant demographic factors were retained in the primary model, which tested the added effects of temperament pattern on the overall intercept and effect of time. This model tested whether there was significant variance in initial mean scores of clinical outcomes given temperament group status, and whether there was significant variance in growth patterns given temperament group status. For these models, temperament group was treated as a factor, with dummy codes for the inhibited and under-controlled groups included in the model. The well-adjusted pattern was treated as the reference for the dummy-coded patterns. Effect sizes accounting for measurement error were tested (Raudenbush & Xiao-Feng, 2001). Lastly, ANOVAs and Tukey-family contrasts were used to determine whether temperament groups significantly differed in final outcomes at 6-month follow-up.

Analytical software

SPSS 23.0 (IBM, 2016) was used to compute imputations for missing data at follow-up assessments. The R computing program (R Core Team, 2016; RStudio Team, 2015) was used to compute clusters and hierarchical linear models. The cluster (Maechler, Rousseeuw, Struf, Hubert, & Hornik, 2016), lme4 (Bates, Maechler, Bolker, & Walker, 2015) lmerTest (Kuznetsova, Brockhoff, & Christensen, 2016), and lsmeans (Lenth, 2016), packages were used in computing results.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive analyses

Table 1 provides the descriptives for study variables at each time point. Eight children were missing baseline temperament scores and could not be included in ongoing analyses. Although these children were older (M age diff = 1.25 (.16), t(123) = 2.24, p = .027, they did not differ along the clinician- or mother-reports at the various assessment time points (ps > .167).

Table 1.

Descriptives of Study Variables

| Pre-Treatment | Post-Treatment | 1 Month Follow- Up |

6 Month Follow- Up |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgency | 3.20 (.57) | -- | -- | -- |

| Effortful Control | 3.25 (.69) | -- | -- | -- |

| Negative Affectivity | 2.55 (.51) | -- | -- | -- |

| Internalizing Symptoms | 58.28 (9.01) | -- | 51.36 (9.05) | 57.20 (11.00) |

| Externalizing Symptoms | 51.17 (9.43) | -- | 48.74 (7.74) | 53.50 (11.07) |

| Phobia Severity (CSR) | 6.68 (.97) | 4.45 (1.71) | 3.60 (1.88) | 2.78 (1.90) |

| CGAS | 61.80 (6.36) | 67.62 (6.88) | 68.84 (7.88) | 70.22 (8.48) |

Note. Internalizing symptom and externalizing symptom reports are T-scored. CSR = Clinician Severity Rating; CGAS = Children’s Global Assessment Scale.

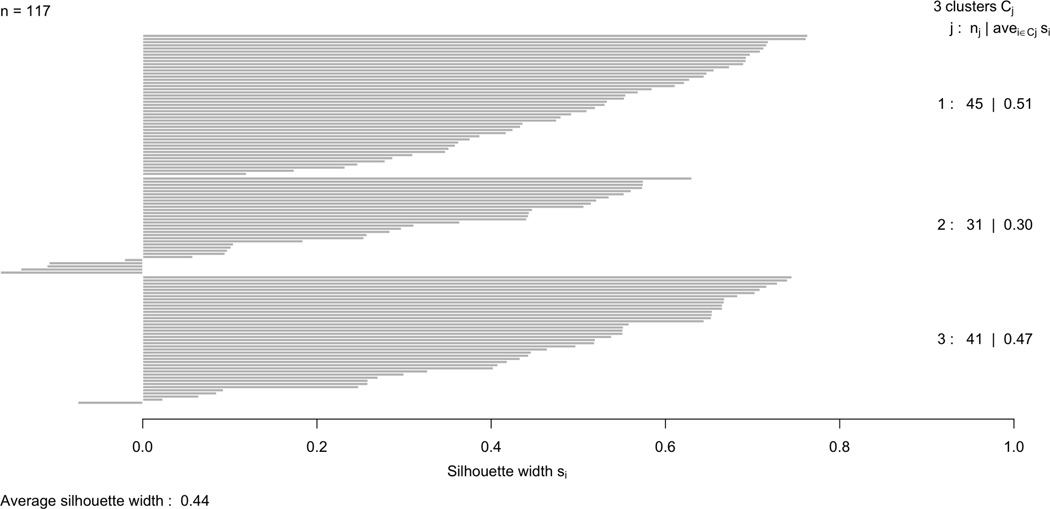

Cluster analysis

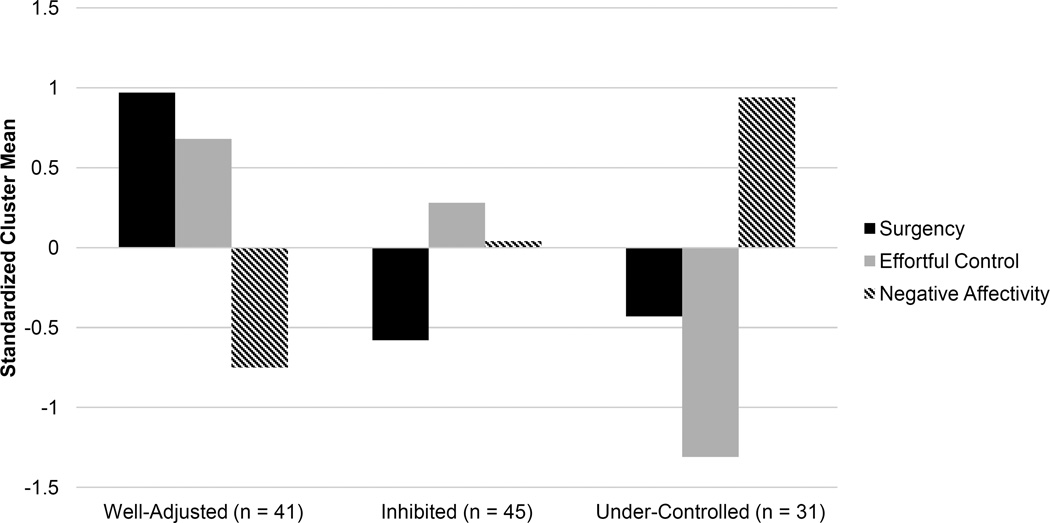

Two-solution, three-solution, and four-solution k-means cluster patterns were tested from the three superscales of the EATQ-R (surgency, effortful control, negative affect). The ratio of within-cluster to total variance accounted for by two-cluster solution was notably lower (37.9%) relative to the three-cluster (53.0%) and four-cluster (59.3%) solutions. Using silhouette plots (Roosseeuw, 1987), clusters were depicted to visually determine the robustness of patterns. The three-cluster solution depicted clusters with more consistent widths and wider average widths, indicating a more robust solution, such that clusters better discriminated and items were less likely to show exceeding distance from cluster centers. Figure 1 depicts this silhouette plot. The emergent clusters were conceptually similar to previous temperamental patterns identified by Caspi and Silva (1995): a well-adjusted group (higher surgency, higher effortful control, and lower negative affect); an inhibited group (lower surgency, moderate effortful control, and moderate negative affect); and an under-controlled group (lower surgency, lower effortful control, and higher negative affect). Figure 2 presents the standardized cluster means for these temperament groups.

Figure 1.

Silhouette Plots of Three-Cluster k-Means Solutions.

Figure 2.

Standardized Cluster Means of Temperament Superscales.

A one-way ANOVA did not find differences in child age, given temperament group (F(2, 114) = .79, p = .455, η2 = .014). However, a chi-square test did support an association between gender and temperament group (χ2(2) = 9.99, p = .007). A greater proportion of boys were in the under-controlled group and a greater proportion of girls were in the inhibited group. Similar proportions of girls and boys were in the well-adjusted group.

Chi-square tests also supported differences in comorbid diagnoses (ADs, ODD, ADHD) between temperament groups. Frequencies of comorbidity for each temperament profile are presented in Table 2. There was an association of temperament group and comorbid AD diagnosis (i.e., generalized anxiety, social anxiety, separation anxiety; χ2(2) = 14.13, p < .001): children in the well-adjusted group showed proportionally fewer comorbid AD diagnoses, children in the under-controlled group showed proportionally more comorbid AD diagnoses, and children in the inhibited group were intermediate. There was also an association of temperament group and ODD comorbid diagnoses (χ2(2) = 9.20, p = .010). The well-adjusted group showed proportionally fewer ODD diagnoses, whereas the under-controlled group showed a greater proportion of ODD comorbidity and the inhibited group was intermediate. Lastly, there was an association of temperament group and ADHD comorbid diagnosis (χ2(2) = 36.13, p < .001). Children in the well-adjusted and inhibited groups were proportionally less-likely to be diagnosed with ADHD, whereas children in the under-controlled group were proportionally more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD.

Table 2.

Cross-Tabulation of Temperament Group and Comorbid Diagnosis

| Anxiety Disorders | Oppositional Defiant Disorder |

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Comorbidity |

Comorbidity | Total | No Comorbidity |

Comorbidity | Total | No Comorbidity |

Comorbidity | Total | |

| Well-Adjusted | |||||||||

| Count | 33a | 8b | 41 | 40a | 1b | 41 | 38a | 3b | 41 |

| % within Group | 80.5% | 19.5% | 100.0% | 97.6% | 2.4% | 100.0% | 92.7% | 7.3% | 100.0% |

| % Within Diagnosis | 48.5% | 16.3% | 35.0% | 38.8% | 7.1% | 35.0% | 43.2% | 10.3% | 35.0% |

| % of Total | 28.2% | 6.8% | 35.0% | 34.2% | 0.9% | 35.0% | 32.5% | 2.6% | 35.0% |

| Inhibited | |||||||||

| Count | 23a | 22a | 45 | 40a | 5a | 45 | 39a | 6b | 45 |

| % within Group | 51.1% | 48.9% | 100.0% | 88.9% | 11.1% | 100.0% | 86.7% | 13.3% | 100.0% |

| % Within Diagnosis | 33.8% | 44.9% | 38.5% | 38.8% | 35.7% | 38.5% | 44.3% | 20.7% | 38.5% |

| % of Total | 19.7% | 18.8% | 38.5% | 34.2% | 4.3% | 38.5% | 33.3% | 5.1% | 38.5% |

| Under-controlled | |||||||||

| Count | 12a | 19b | 31 | 23a | 8b | 31 | 11a | 20b | 31 |

| % within Group | 38.7% | 61.3% | 100.0% | 74.2% | 25.8% | 100.0% | 35.5% | 64.5% | 100.0% |

| % Within Diagnosis | 17.6% | 38.8% | 26.5% | 22.3% | 57.1% | 26.5% | 12.5% | 69.0% | 26.5% |

| % of Total | 10.3% | 16.2% | 26.5% | 19.7% | 6.8% | 26.5% | 9.4% | 17.1% | 26.5% |

| Total Count | 68 | 49 | 117 | 103 | 14 | 117 | 88 | 29 | 117 |

| % within Group | 58.1% | 41.9% | 100.0% | 88.0% | 12.0% | 100.0% | 75.2% | 24.8% | 100.0% |

Note. Shared subscripts indicate there is not a significant difference in column proportions. Bonferroni-family corrections were incorporated in testing differences in column proportions.

Hypothesis Tests

Table 3 presents the fixed effects for HLM tests of mother-reported internalizing and externalizing symptoms on the CBCL and clinician-reported phobia severity and CGAS.

Table 3.

Growth Model Fixed Effects of Mother- and Clinician-Reported Outcomes

| Internalizing Symptoms (CBCL) | Externalizing Symptoms (CBCL) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | SE | 95% CI | β | Sig. | d | Est. | SE | 95% CI | β | Sig. | d | |||

| Intercept | 48.70 | 1.07 | 46.60 | 50.80 | -- | .000 | -- | 46.72 | .99 | 44.77 | 48.66 | -- | .000 | ---- |

| Anxiety Com. | 5.67 | 1.14 | 3.44 | 7.90 | .28 | .000 | .71 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| ODD Com. | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 9.56 | 1.94 | 5.75 | 13.36 | .32 | .000 | 1.19 |

| ADHD Com. | 4.17 | 1.31 | 1.60 | 6.73 | .18 | .002 | .52 | 4.35 | 1.45 | 1.50 | 7.19 | .19 | .003 | .54 |

| Inhibited | 4.44 | 1.70 | 7.17 | 1.40 | .22 | .002 | .56 | −.02 | 1.07 | −2.11 | 2.08 | −.00 | .988 | −.00 |

| Under-Controlled | 5.74 | 1.60 | 2.61 | 8.87 | .25 | .000 | .72 | 3.93 | 1.18 | 1.61 | 6.24 | .17 | .001 | .49 |

| Time (in Months) | 1.02 | .29 | .45 | 1.60 | .28 | .000 | .13 | 1.05 | .26 | .53 | 1.57 | .30 | .000 | .13 |

| Inhibited | −1.37 | .41 | −2.18 | −.56 | −.30 | .001 | −.17 | −.74 | .36 | −1.46 | −.03 | −.16 | .042 | −.09 |

| Under-Controlled | −1.11 | .47 | −2.04 | −.19 | −.20 | .020 | −.14 | −.84 | .41 | −1.65 | −.04 | −.15 | .042 | −.10 |

| Phobia Severity (CSR) | Global Assessment (CGAS) | |||||||||||||

| Est. | SE | 95% CI | β | Sig. | d | Est. | SE | 95% CI | β | Sig. | d | |||

| Intercept | 4.95 | .21 | 4.53 | 5.37 | -- | .000 | -- | 69.60 | .78 | 68.07 | 71.12 | -- | .000 | -- |

| Gender (Female) | .43 | .22 | −.01 | .87 | .10 | .056 | .24 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Anxiety Com. | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | −6.14 | .95 | −7.99 | −4.29 | −.37 | .000 | −.96 |

| ODD Com. | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | −3.28 | 1.48 | −6.17 | −.39 | −.13 | .028 | −.51 |

| ADHD Com. | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | −2.75 | 1.12 | −4.93 | −.56 | −.15 | .015 | −.43 |

| Inhibited | .01 | .25 | −.49 | .51 | .00 | .958 | .01 | −1.11 | .86 | −2.80 | .58 | −.07 | .200 | −.17 |

| Under-Controlled | .36 | .28 | −.19 | .91 | .07 | .204 | .20 | −.76 | .96 | −2.65 | 1.12 | −.04 | .427 | −.12 |

| Time (in Months) | −.48 | .05 | −.58 | −.37 | −.56 | .000 | −.27 | .86 | .17 | −2.65 | 1.12 | .27 | .000 | .13 |

| Inhibited | .13 | .07 | −.01 | .28 | .12 | .074 | .07 | −.09 | .24 | −.57 | .38 | −.02 | .699 | −.01 |

| Under-Controlled | .01 | .08 | −.16 | .18 | .01 | .895 | .01 | −.10 | .27 | −.63 | .44 | −.02 | .723 | −.02 |

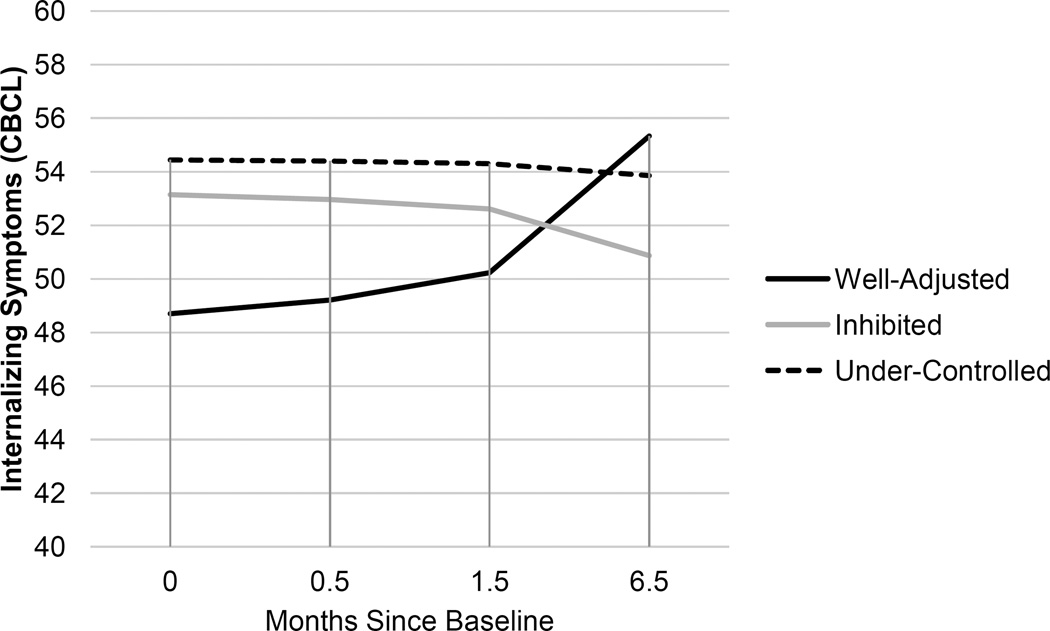

Internalizing symptoms

For mother reports of internalizing symptoms, the preliminary model supported significant effects of anxiety comorbidity and ADHD comorbidity on the intercept. Children with anxiety and ADHD comorbidities had higher initial internalizing symptoms. Across the sample, internalizing symptoms decreased over time. After accounting for comorbidity, the well-adjusted group showed an increase in internalizing symptoms over time. However, importantly, this increase in internalizing symptoms remained within the normal range. The inhibited group had higher initial values of internalizing symptoms than the well-adjusted group. This group showed greater declines over time, relative to the well-adjusted group. The under-controlled group also had higher initial values of internalizing symptoms than the well-adjusted group. This group also showed significantly greater declines in internalizing symptoms relative to the well-adjusted group. Figure 3 depicts these group trends.1

Figure 3.

Growth Trends of Internalizing Symptoms between Temperament Profiles. Depicted starting values assumed children were girls with no comorbid diagnoses.

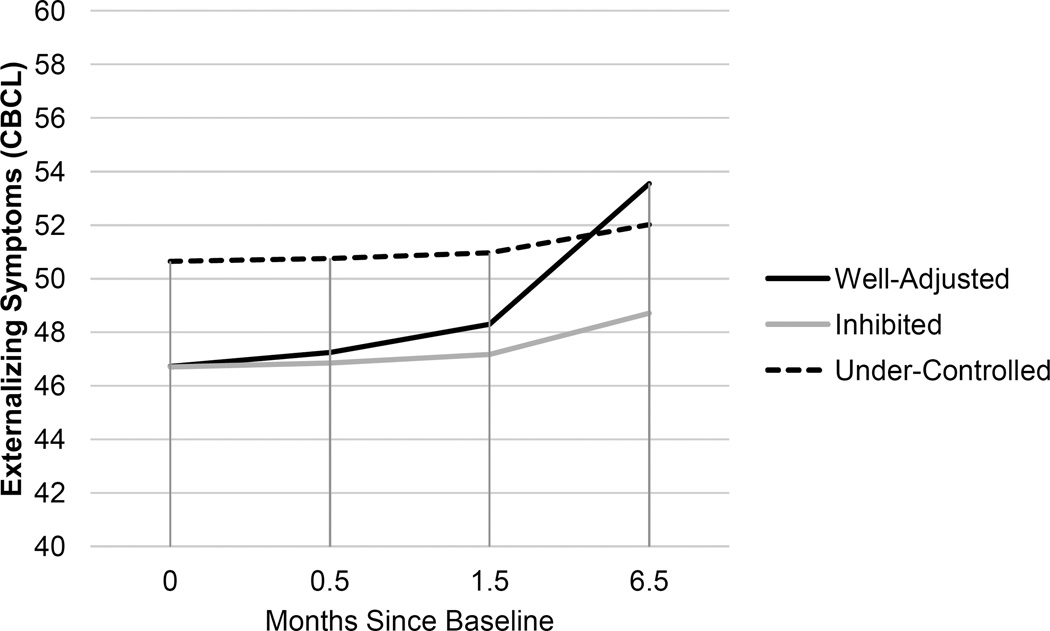

Externalizing symptoms

For mother reports of externalizing symptoms on the CBCL, the preliminary model supported significant effects of ODD and ADHD comorbidities on the intercept. There was not a significant decrease in symptoms across the sample as a whole. After accounting for comorbidity, the well-adjusted group increased in externalizing symptoms over time. However, as with internalizing symptoms, this increase in externalizing symptoms remained well within the normal range. The inhibited group did not significantly differ from the well-adjusted group in initial values. However, this group did show a significantly different and attenuated pattern of growth from the well-adjusted group. The under-controlled group had significantly higher values of externalizing symptoms than the well-adjusted group at baseline. This group also showed a significantly different and attenuated growth trend from the well-adjusted group. Figure 4 depicts these trends.

Figure 4.

Growth Trends of Externalizing Symptoms among Temperament Profiles. Depicted starting values assumed children were girls with no comorbid diagnoses.

Phobia clinical severity

For clinician reports of phobia severity, the preliminary model supported an initial gender effect that did not remain significant when temperament effects were included. There was a decrease in clinical severity across the entire sample over time. After accounting for demographics, all groups showed comparable starting values of severity and similarly decreased in severity.

Global assessment

For clinician reports of global outcomes, the preliminary model did not support age or gender effects on the intercept; however, each comorbid diagnosis predicted poorer initial CGAS. Across the sample, children showed improvements over time. After accounting for comorbidity, all three groups showed similar improvements over time.

ANOVAs of Group Differences at 6-Month Follow-Up

ANOVAs testing temperament group differences at 6-month follow-up did not find significant group differences for internalizing symptoms (F(2, 114) = 2.76, p = .068, η2 = .046), externalizing symptoms (F(2, 114) = 1.93, p = .149, η2 = .033), or phobia severity (F(2, 114) = .63, p = .543, η2 = .011). However, ANOVAs did support group differences for the CGAS (F(2, 114) = 22.32, p < .001, η2 = .282). Tukey-family contrasts were significant between each temperament group (ps < .004). The well-adjusted group (M = 75.07 (6.96)) had significantly higher scores than the other two groups. The under-controlled group (M = 63.61 (6.23)) had significantly lower scores than the other two groups. The inhibited group (M = 70.00 (8.00)) was between the other two groups, and showed significant differences from each.

Discussion

The present study considered the potential role of temperamental patterns on clinical outcomes following one-session treatments of SPs. This study was based on extant literature considering the implications of temperament on child and adolescent adjustment (Goldsmith et al., 1987), and extended consideration of person-level temperamental profiles on outcomes of adjustment (Caspi & Silva, 1995; Caspi et al., 2003; Thomas & Chess, 1977). We expected multiple temperamental groups to emerge within this phobic sample and for these groups to resemble those previously found in broader community samples (e.g., Caspi & Silva, 1995), with archetypes of well-adjusted, inhibited, and under-controlled group patterns. Finally, we expected groups with optimal reports across surgency, negative affect, and effortful control to show greater clinical outcomes than groups depicting deficiencies in one or more of these areas.

Findings were partly in line with our hypotheses regarding a) the existence of temperament patterns within a sample of children with SPs, and b) differing trajectories of CBT outcomes among temperament groups. Three patterns of temperament were supported within the current sample. These patterns resembled those previously identified in child temperament research (Caspi et al., 2003; Caspi & Silva, 1995; Eisenberg et al., 2001; McClowry, 2002). A well-adjusted group emerged, with relatively more effortful control and surgency, as well as less negative affectivity. This group was unlikely to have comorbid internalizing and externalizing diagnoses and showed benefits in clinician-reported global clinical outcomes relative to other groups, but did not show lasting differential benefits in mother-reported internalizing and externalizing symptoms. An inhibited group emerged with particularly low surgency and moderate reports of effortful control and negative affectivity. This group was reported to have more initial internalizing symptoms than the well-adjusted group and poorer global clinical outlook than the well-adjusted group at 6-month follow-up. Lastly, an under-controlled group emerged with low surgency and effortful control, as well as high negative affectivity. As with previous studies (Caspi & Silva, 1995), this group had disproportionate comorbidity with additional anxiety, ODD, and ADHD diagnoses. This group also had higher initial reports of internalizing and externalizing symptoms, and poorer average global clinical outcomes relative to the other groups at 6-month follow-up. The proportions of children placed in the inhibited and under-controlled groups were larger than in previous studies of non-referred children (Caspi et al., 2003). This was not surprising given the clinical nature of our sample.

These findings suggest there is considerable heterogeneity in temperament among youth with SPs. Although SPs have been traditionally classified within the inhibited, fear-subtype of internalizing disorders (Salum et al., 2013; Waters, Bradley, & Mogg, 2014), such disorders may present more complex profiles alongside classifications of elevated avoidance and fear responses. Hence, approaches which assume temperament is homogenous and characterized by elevated inhibition in such samples may not be totally accurate. Despite these temperament differences, our overall findings suggest that OST remains an effective treatment for childhood SPs.

However, the extent to which temperament profiles predicted expected outcomes was mixed, underscoring the utility of the different temperament profiles and important informant differences. Surprisingly, mothers—who were also the reporters of child temperament—reported greater long-term improvements for those outside of the well-adjusted temperament group, whereas clinicians reported consensus global outcome differences in favor of the well-adjusted group. Mothers’ reports of temperament did show acceptable internal consistency. It is possible that mothers’ expectations for children’s ongoing improvements were skewed by earlier perceptions of temperament, or that children with less adaptive temperamental styles were more responsive in ongoing internalizing and externalizing behaviors in the home setting. Additional work will be needed to clarify possible moderating factors pertinent to these children and their families.

Two interesting sex trends emerged in this sample. In regard to profile placement, girls were disproportionately placed in the inhibited temperamental group whereas boys were disproportionately placed in the under-controlled group. These trends resemble previous community-sample patterns (e.g., McClowry, 2002). The well-adjusted group was represented by similar numbers of girls and boys from the sample. The inhibited group was marked by lowest reports of surgency, indicating poorer pleasure-seeking, as well as greater fear and shyness. Surprisingly, this group was not diagnosed with comorbid anxiety disorders at a disproportionate rate, unlike the under-controlled group, which was disproportionately diagnosed with both internalizing and externalizing comorbid disorders. This finding is surprising in terms of internalizing symptoms, as girls are typically at higher risk for internalizing symptoms, whereas boys are typically at higher risk for externalizing symptoms (Zahn-Waxler, Shirtcliff, & Marceau, 2008). However, given that this was a treatment-seeking sample for severely impairing phobias who also possessed related anxiety disorders, boys may have shown marked concerns in internalizing symptoms that exceed those typically seen in non-referred samples of boys.

A primary limitation of the present study was the lack of diversity in regards to our sample. Participants and their mothers were predominantly Caucasian, which limits our ability to generalize our findings across diverse races and ethnicities. As such, future research should explore the role of temperament in relation to clinical and treatment outcomes for more culturally and ethnically diverse youth with SPs. Furthermore, only maternal reports of child’s temperament as well as internalizing and externalizing symptoms were examined. Children’s perceptions might have offered additional information regarding the role of temperament and its potential relations to treatment responsiveness. Given the relatively young mean age of our sample (under 11 years of age), we did not find it appropriate to assess the child’s report because the indices used are not normed for such children (Achenbach, 1991). Future research might also examine paternal reports of temperament as well to see if similar differences to those obtained with mothers exist.

Despite these limitations, this study is the first to longitudinally examine the role of temperamental patterns on clinical outcomes following treatment for SPs. Moreover, this study is novel in its person-centered conceptualization in youth with SPs. Importantly, our analyses used multiple informants (mothers and clinicians), reducing concerns of reporter bias. As we await more research to better understand the processes underlying varying responsiveness following CBT-based therapies, we suggest that more nuanced consideration of temperamental patterns may further inform pathways of treatment response for youth with SPs. While we know of no specific clinical recommendations for treatment in response to temperament profiles, longitudinal trends for these profiles have shown areas of risk for inhibited and under-controlled youth (Caspi et al., 2003). Inhibited youth have shown elevated risks for ongoing social withdrawal and limited pleasure-seeking. Youth with this profile may benefit from supplementary social competence and emotion regulation skill development. Alternatively, under-controlled youth show elevated risks for ongoing irritability and antagonistic behaviors. Youth with this profile may benefit from longer-term interventions to address under-regulation and emotional lability, such as approaches from traditional ODD-based interventions. At present, our findings suggest that more nuanced approaches might provide particular insight in anticipating additional needs for youth with an under-controlled profile, given the additional problems reported by mothers and clinicians in this group.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health, Grant R01 MH074777.

Footnotes

For the sake of simplicity, we do not present trendlines accounting for differences based on comorbidity with anxiety, ODD, and ADHD.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of Interest The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont; 1991. p. 288. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Dumenci L, Rescorla LA. DSM-oriented and empirically based approaches to constructing scales from the same item pools. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:328–340. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, (DSM-IV) Washington D.C: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM. Washington D.C: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software. 2015;67:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Canino G, Rubio-Stipec M, Ribera JC. Further measures of the psychometric properties of the Children’s Global Assessment Scale. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;44:821–824. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800210069011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Fox NA. Self-regulatory processes in early personality development: A multilevel approach to the study of childhood social withdrawal and aggression. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:477–498. doi: 10.1017/s095457940200305x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Harrington H, Milne B, Amell JW, Theodore RF, Moffitt TE. Children’s behavioral styles at age 3 are linked to their adult personality traits at age 26. Journal of Personality. 2003;71:495–514. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7104001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Henry B, McGee RO, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. Temperamental origins of child and adolescent behavior problems: From age three to age fifteen. Child Development. 1995;66:55–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Silva PA. Temperamental qualities at age three predict personality traits in young adulthood: Longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Child Development. 1995;66:486–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pauw SS, Mervielde I. The role of temperament and personality in problem behaviors of children with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39:277–291. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9459-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Reiser M, Guthrie IK. The relations of regulation and emotionality to children’s externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Development. 2001;72:1112–1134. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis LK, Rothbart MK. Revision of the early adolescent temperament questionnaire. Poster presented at the 2001 biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Minneapolis, Minnesota. 2001 Apr [Google Scholar]

- Essau CA, Conradt J, Petermann F. Frequency, comorbidity, and psychosocial impairment of specific phobia in adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29:221–231. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp2902_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festen H, Hartman CA, Hogendoorn S, de Haan E, Prins PJ, Reichart CG, Nauta MH. Temperament and parenting predicting anxiety change in cognitive behavioral therapy: The role of mothers, fathers, and children. Journal of Anxiety, Disorders. 2013;27:289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH, Buss AH, Plomin R, Rothbart MK, Thomas A, Chess S, McCall RB. Roundtable: What is temperament? Four approaches. Child Development. 1987;58:505–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green B, Shirk S, Hanze D, Wanstrath J. The Children’s Global Assessment Scale in clinical practice: An empirical evaluation. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1994;33:1158–1164. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199410000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higa-McMillan CK, Smith RL, Chorpita BF, Hayashi K. Common and unique factors associated with DSM-IV-TR internalizing disorders in children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:1279–1288. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2016. Released. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Snidman N. Early childhood predictors of adult anxiety disorders. Biological Psychiatry. 1999;46:1536–1541. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Snidman N, Kahn V, Towsley S. The preservation of two infant temperaments through adolescence. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2007;72 doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2007.00436.x. Serial No. 287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Safford S, Flannery-Schroeder E, Webb A. Child anxiety treatment: Outcomes in adolescence and impact on substance use and depression at 7.4-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:276–287. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, Christensen RHB. lmerTest: Tests in linear mixed effects models. R package version 2.0–30. 2016 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lmerTest.

- Lenth RV. Least-squares means: The R package lsmeans. Journal of Statistical Software. 2016;69:1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lonigan CJ, Phillips BM. Temperamental influences on the development of anxiety disorders. In: Vasey MW, Dadds MR, editors. The developmental psychopathology of anxiety. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 60–91. [Google Scholar]

- Maechler M, Rousseeuw P, Struyf A, Hubert M, Hornik K. Cluster: Cluster analysis basics and extensions. R package version 2.0.4. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- McClowry SG. The temperament profiles of school-age children. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2002;17:3–10. doi: 10.1053/jpdn.2002.30929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Swendsen J. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent Supplement (NCSA) Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Ollendick TH. The role of temperament in the etiology of child psychopathology. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2005;8:271–289. doi: 10.1007/s10567-005-8809-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT. Temperament and developmental psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:395–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oar EL, Farrell LJ, Waters AM, Ollendick TH. Blood-injection-injury phobia and dog phobia in youth: Psychological characteristics and associated features in a clinical sample. Behavior Therapy. 2016;47:312–324. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldehinkel AJ, Hartman CA, De Winter AF, Veenstra R, Ormel J. Temperament profiles associated with internalizing and externalizing problems in preadolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:421–440. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick TH, Davis TE., III One-session treatment for specific phobias: A review of Öst’s single-session exposure with children and adolescents. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2013;42:275–283. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2013.773062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick TH, Halldorsdottir T, Fraire MG, Austin KE, Noguchi RJ, Lewis KM, Whitmore MJ. Specific phobias in youth: A randomized controlled trial comparing one-session treatment to a parent-augmented one-session treatment. Behavior Therapy. 2015;46:141–155. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick TH, King NJ, Muris P. Phobias in children and adolescents: A review. Phobias. 2004;7:245–302. [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick TH, Öst LG, Reuterskiöld L, Costa N, Cederlund R, Sirbu C, Jarrett MA. One-session treatment of specific phobias in youth: A randomized clinical trial in the United States and Sweden. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:504–516. doi: 10.1037/a0015158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öst L-G. One-session treatment for specific phobias. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1989;27:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(89)90113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öst L-G. Rapid treatment of specific phobias. In: Davey GCL, editor. Phobias: A handbook of theory, research and treatment. Oxford, England: Wiley; 1997. pp. 227–247. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam SP, Ellis LK, Rothbart MK. The structure of temperament from infancy through adolescence. In: Eliasz A, Anglietner A, editors. Advances in research on temperament. Lengerich, Germany: Pabst Science Publishers; 2001. pp. 164–182. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2016 URL https://www.R-project.org/

- Rapee RM, Coplan RJ. Conceptual relations between anxiety disorder and fearful temperament. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2010;2010:17–31. doi: 10.1002/cd.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Xiao-Feng L. Effects of study duration, frequency of observation, and sample size on power in studies of group differences in polynomial change. Psychological Methods. 2001;6:387–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseeuw PJ. Silhouettes: A graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics. 1987;20:53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Hershey KL, Fisher P. Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: The Children’s Behavior Questionnaire. Child Development. 2001;72:1394–1408. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Bates JE. Temperament. In: Eisenberg N, Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3, Social, emotional, and personality development. 6th. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2006. pp. 99–166. [Google Scholar]

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, Inc. Boston, MA: 2015. URL http://www.rstudio.com/ [Google Scholar]

- Salum GA, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Gadelha A, Pan P, Tamanaha AC, do Rosario MC. Threat bias in attention orienting: Evidence of specificity in a large community-based study. Psychological Medicine. 2013;43:733–745. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Fisher P, Bird H, Aluwahlia S. A children’s global assessment scale (CGAS) Archives of General Psychiatry. 1983;40:1228–1231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Albano AM. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (Child and Parent Versions) San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Kurtines WM, Ginsburg GS, Weems CF, Rabian B, Serafini LT. Contingency management, self-control, and education support in the treatment of childhood phobic disorders: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:675–687. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.5.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A, Chess S. Temperament and development. New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- van Brakel AML, Muris P. A brief scale for measuring “behavioral inhibition to the unfamiliar” in children. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2006;28:79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Vervoort L, Wolters LH, Hogendoorn SM, Prins PJ, de Haan E, Boer F, Hartman CA. Temperament, attentional processes, and anxiety: Diverging links between adolescents with and without anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40:144–155. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.533412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters AM, Bradley BP, Mogg K. Biased attention to threat in pediatric anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, separation anxiety disorder) as a function of ‘distress’ versus ‘fear’ diagnostic categorization. Psychological Medicine. 2014;44:607–616. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713000779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn-Waxler C, Shirtcliff EA, Marceau K. Disorders of childhood and adolescence: Gender and psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:275–303. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]