Abstract

The c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) has been shown to be an important regulator of neuronal cell death. Previously, we synthesized the sodium salt of 11H-indeno[1,2-b]quinoxalin-11-one (IQ-1S) and demonstrated that it was a high-affinity inhibitor of the JNK family. In the present work, we found that IQ-1S could release nitric oxide (NO) during its enzymatic metabolism by liver microsomes. Moreover, serum nitrite/nitrate concentration in mice increased after intraperitoneal injection of IQ-1S. Because of these dual actions as JNK inhibitor and NO-donor, the therapeutic potential of IQ-1S was evaluated in an animal stroke model. We subjected wild-type C57BL6 mice to focal ischemia (30 minutes) with subsequent reperfusion (48 hours). Mice were treated with IQ-1S (25 mg/kg) suspended in 10% solutol or with vehicle alone 30 minutes before and 24 hours after middle cerebral artery MCA) occlusion (MCAO). Using laser-Doppler flowmetry, we monitored cerebral blood flow (CBF) above the MCA during 30 minutes of MCAO provoked by a filament and during the first 30 minutes of subsequent reperfusion. In mice treated with IQ-1S, ischemic and reperfusion values of CBF were not different from vehicle-treated mice. However, IQ-1S treated mice demonstrated markedly reduced neurological deficit and infarct volumes as compared with vehicle-treated mice after 48 hours of reperfusion. Our results indicate that the novel JNK inhibitor releases NO during its oxidoreductive bioconversion and improves stroke outcome in a mouse model of cerebral reperfusion. We conclude that IQ-1S is a promising dual functional agent for the treatment of cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury.

Keywords: c-Jun N-terminal kinase, cerebral reperfusion, nitric oxide

1. Introduction

Reperfusion injury is a major clinical problem in several organs, including heart, liver, kidney, and brain. The important role of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) has been demonstrated in the pathogenesis of reperfusion injury and stroke [29, 51]. C-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) is a critical MAPK activated by various brain insults and is implicated in neuronal injury triggered by reperfusion-induced oxidative stress [13, 37]. Three distinct JNKs, designated as JNK1, JNK2, and JNK3, have been identified, and at least 10 different splicing isoforms exist in mammalian cells [23]. While JNK1 and JNK2 are ubiquitously expressed, JNK3 is found almost exclusively in the brain [56], but it is not dominant, as JNK3 knockout results only in a weak attenuation of the total JNK pool in brain tissue [6]. Increased JNK phosphorylation and JNK activity in the hippocampus have been reported after global cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury [20, 25, 36, 50]. Sustained JNK activation has been shown to be associated with neuronal death and apoptosis following ischemic stroke, and in animal models of cerebral ischemia, acute inhibition of JNK reduces infarction and improves outcomes [16, 22, 38]. Inhibition of the JNK pathway also improves behavioral outcome after neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury [39]. Because the inhibition of JNK isoforms has neuroprotective effects in animal models of stroke, it has been suggested that pan-JNK inhibitors may represent promising therapeutic agents for treatment of brain insults.

Increasing evidence suggests that the JNK signaling pathway is tightly coupled with nitric oxide (NO) production during ischemia and reperfusion [58]. The effects of NO on the ischemic brain are thought to be dependent on the sources of its production and the stage of the ischemic process [11, 15, 26, 34, 44, 45]. The low concentration of NO that is produced by endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) confers protective effects during cerebral ischemia [34], whereas the high concentrations of NO produced from neuronal NOS (nNOS) and inducible NOS (iNOS) are detrimental to the ischemic brain [11, 35]. Exogenous NO had a neuroprotective role in reperfusion-induced brain injury [26, 35, 44, 45]. Based on the coupling of NO and JNK pathways and the protective role of exogenous NO, we hypothesized that agents with dual functions as JNK inhibitors and NO donors could have protective effects against cerebral reperfusion injury. To date, some oxime derivatives have been demonstrated in vivo and ex vivo as NO donors [12, 18, 28, 42]. Recently, we described novel oxime-derived, specific JNK inhibitors based on the 11H-indeno[1,2-b]quinoxalin-11-one scaffold [46, 47]. One of these compounds, IQ-1S, was found to be active in vivo and had a higher affinity toward JNK3 over JNK1/JNK2 [46, 47]. Because the neutral form of IQ-1S has an oxime group, we suggest that, similar to other aryl oxime derivatives [1, 10, 12], this compound could release NO during its oxidoreductive bioconversion and, together with JNK inhibition by the parent molecule, will improve stroke outcome in a model of cerebral reperfusion. Here, we show that indeed, the JNK inhibitor IQ-1S releases NO during its enzymatic metabolism with liver microsomes, resulting in increased serum NO concentration in mice after IQ-1S injection. Moreover, mice treated with IQ-1S demonstrated markedly reduced infarct volume and neurological deficit after 48 hours of reperfusion.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Compounds

Sodium salt of 11H-indeno[1,2-b]quinoxalin-11-one (IQ-1S) was synthesized, as described previously [43], and the structure of the compound was confirmed by NMR and mass spectroscopy [47]. For in vitro experiments, IQ-1S was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (EMD Chemicals, Darmstadt, Germany); for animal treatment, IQ-1S was suspended in 10% solutol HS15 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

2.2. Determination of NO in microsomal suspension and serum

Pooled liver microsomes from male CD-1 mice were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. IQ-1S was incubated for the indicated times with the microsomal suspension (2 mg/ml) and NADPH (2 mM) in potassium phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH 7.4; 37 °C). Control samples contained DMSO (up to 2 %). The incubation was ended by heating the reaction for 5 min at 100°C, and the mixture was centrifuged (10 min × 10,000 g). Aliquots from the reaction were directly mixed with Griess reagent (equal volumes of 1% sulfanilamide in 0.4 N HCl and 0.1% N-(1-naphtyl)ethylenediamine in 0.4 N HCl) to determine NO2− [10].

After single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of IQ-1S (50 mg/kg; the dose was selected based on the total amount received during treatment in the ischemia model, see below), C57BL6/J mice were bled, and sera were separated. NO production in murine serum was determined by measuring levels of nitrite plus nitrate by the Griess reaction after reduction of nitrate to nitrite by nitrate reductase using a Nitrite/Nitrate Colorimetric Assay Kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). Before the reaction, serum samples were ultrafiltered using 30 kDa molecular weight cut-off filters (Amicon).

2.3. Cerebral reperfusion model

The transient middle cerebral artery (MCA) occlusion (MCAO) model was performed on 10–12 week old male C57BL6/J mice under anesthesia (1.5% isoflurane in 30% O2 and 70% N2O). A fiberoptic probe was affixed to the skull over the area supplied by the MCA for relative cerebral blood flow measurements by laser Doppler flowmetry before, during, and 30 minutes after MCAO. Body temperature was monitored continuously, and temperature was maintained at 36.5°C to 37.5°C with a heating plate (FHC). MCAO was caused by inserting a nylon filament covered by silicon (Doccol) into the internal carotid artery and advancing it to the origin of the MCA for 30 minutes of ischemia with subsequent reperfusion for 48 hours [4]. All procedures were performed in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health and approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Subcommittee on Research and Animal Care.

2.4. Evaluation of neurological deficit

Mice were examined after 48 hours of reperfusion using a 4-point scale, as described previously [4]. Normal motor function was scored as 0, flexion of the contralateral torso and forearm on lifting the animal by the tail as 1, circling to the contralateral side as 2, leaning to the contralateral side at rest as 3, and no spontaneous motor activity as 4.

2.5. Measurement of infarct volume

After measurements of neurological deficit at 48 hr of reperfusion, brains were cut into 2-mm-thick coronal sections and stained with 2% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) for 1 hr at 37°C in the dark [3]. The area of infarction in each section was expressed as a fraction of the non-ischemic part of ipsilateral hemisphere (indirect volume of infarct) [3].

2.6. IQ-1S treatment

Mice were treated intraperitoneally with IQ-1S (25 mg/kg) suspended in 10% solutol (100 μl) or with vehicle (10% solutol, 100 μl) 30 min before and 24 hours after MCAO. This dosing of IQ-1S was selected based on previously published studies that used this compound to target JNK in mouse models in vivo [46, 47]. This dose regimen represents a combination of prophylactic (IQ-1S administration before ischemia-reperfusion) and therapeutic (after reperfusion) treatments. Because an acute (first minutes after stroke) and delayed treatment (5–7 days after stroke) with JNK inhibitors could have different outcomes after focal cerebral ischemia [38], 24 hours after stroke was used for the second administration of IQ-1S.

2.7. Molecular modeling

To evaluate the ability of IQ-1S to permeate the blood-brain barrier (BBB), we calculated parameters important for this permeation [48] using the structure of the neutral form of IQ-1S, which is the most abundant form at physiological pH [46]. The octanol-water partition coefficient aLogP was calculated according to the Ghose-Crippen additive scheme [17] with the use of HyperChem 7.0 software. Polar surface area (tPSA) was obtained by a summation of atomic increments [14]. Number of rotatable bonds (Nrot) was counted directly in the structural formula of the molecule. Based on calculated parameters (aLogP, tPSA, and Nrot) the prediction of BBB permeation for IQ-1S was obtained using previously reported classification trees [48].

2.8. Statistical analysis

All results are expressed as mean ± S.D. Statistical analysis was performed with t-test or Kruskal-Wallis 1-way analysis of variance on ranks (neurological deficit). Differences of p<0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. IQ-1S releases NO

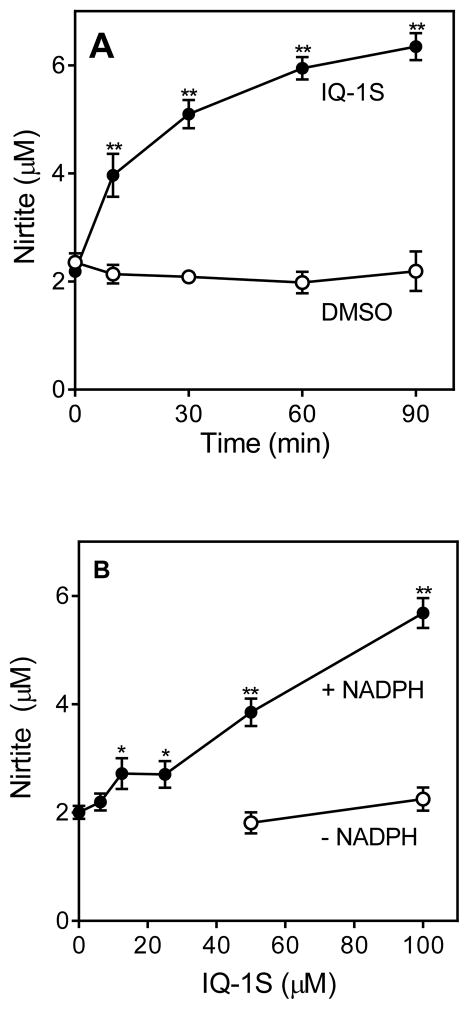

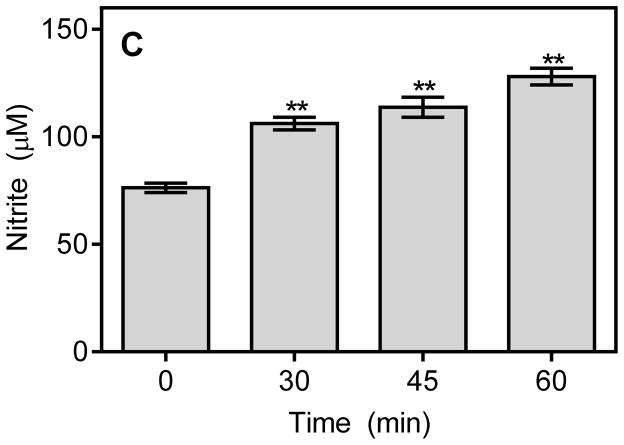

Previous publications reported that aryl oximes could be metabolized by cytochrome P450 and NO synthase to release NO [1, 10, 52]. Because of the biological effects of NO during reperfusion, we studied whether the aryl oxime IQ-1S could act as a NO precursor after an in situ oxidation catalyzed by endogenous enzymes under physiological conditions (liver microsomes with NADPH and O2). The results of our experiments indicate that the NADPH-dependent metabolism of IQ-1S by mouse liver microsomes resulted in accumulation of NO2−, which was formed via oxidation of NO radical (Fig. 1A and B). NO2− production increased linearly with increasing concentrations of IQ-1S but not reaching saturation at 100 μM of the compound. In contrast, incubation of the control DMSO with microsomes did not result in accumulation of NO2−. Production of NO2− was also not observed in the absence of NADPH (Fig. 1B) or with heat-inactivated microsomes (5 min at 100 °C; data not shown), indicating that the cytochrome P450 mixed-function oxidase system was involved in the oxidation IQ-1S, in accordance with the general mechanism of other aryl oximes [1, 10, 52]. Likewise, single administration of IQ-1S (50 mg/kg, i.p.) significantly increased serum nitrite/nitrate concentrations in vivo at 30–60 min after treatment (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

NO production by mouse liver microsomes and in serum.

Panel A. NO production during NADPH-dependent metabolism of IQ-1S by mouse liver microsomes. Compound IQ-1S (100 μM) was incubated with microsomes and 2 mM NADPH for the indicated times, and nitrite production was measured, as described. Panel B. Microsomes were incubated with the indicated concentrations of IQ-1S for 60 min without or with 2 mM NADPH, and nitrite production was measured. Panel C. NO production in serum after IQ-1S injection. IQ-1S was administrated i.p. (single dose 50 mg/kg), mice (n=3) were sacrificed after indicated time, and serum was collected. Serum nitrite levels were evaluated using a Nitrite/Nitrate Colorimetric Assay Kit, as described. For Panels A and B, values are the mean ± S.D. of triplicate samples from one experiment, which is representative of two independent experiments. Statistically significance differences (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01) between IQ-1S- and DMSO-incubated microsomes are indicated. For Panel C, the data are presented as means ± S.D. of triplicate samples from different mice and are representative of two independent experiments. Statistically significance differences (** p<0.01) between animals treated with IQ-1S and vehicle are indicated.

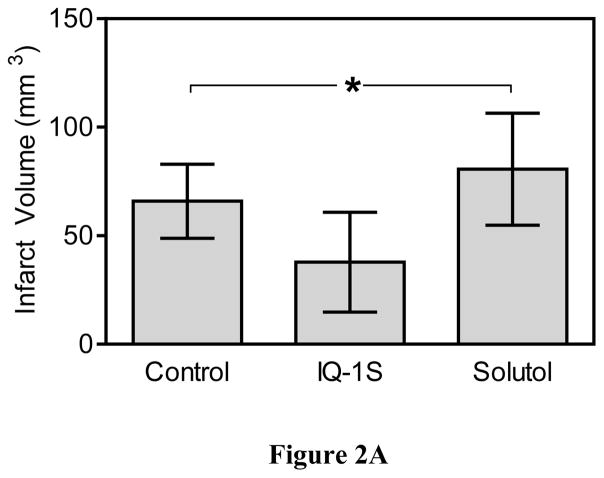

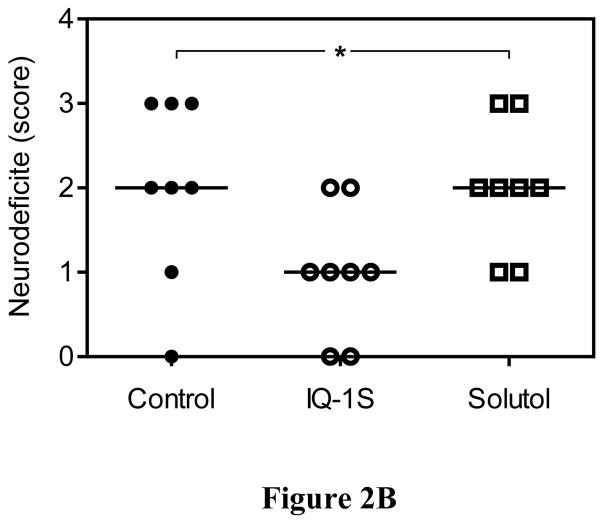

3.2. IQ-1S decreased reperfusion injury

After 30 minutes of MCAO and 48 hours of reperfusion, mice exhibited significant infarct damage (Fig. 2). To ensure that comparable ischemic insults were reproducibly induced, we used laser Doppler to monitor the decrease in cortical perfusion and confirmed no differences between mouse groups in cerebral blood flow during MCAO and the first 30 minutes of reperfusion. Compared to the control untreated and vehicle-treated mice, two injections of IQ-1S administered 30 minutes before and 24 hours after MCAO significantly reduced infarct volumes measured at 48 hours after reperfusion (Fig. 2A). Moreover, mice treated with IQ-1S demonstrated less severe neurological deficit after 48 hours of reperfusion, as compared to control untreated and vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 2B). In the course of these studies, 3 animals died in each of the control and vehicle-treated groups of mice, whereas 2 animals died in the IQ-1S-treated group. All deaths occurred during the first night after stroke surgery. These animals were excluded from statistical evaluation of infarct volume and neurological deficit.

Figure 2.

IQ-1S treatment improved stroke outcome.

Panel A. IQ-1S decreased infarct volume. Mice were treated with IQ-1S (i.p., 25 mg/kg) or with vehicle control (10% solutol), 30 minutes before and 24 hours after MCAO or without any treatment (control). After 48 hours of reperfusion, the animals were euthanized, and the area of infarction in stained brain sections was measured. The data are expressed as a fraction of the non-ischemic part of ipsilateral hemisphere. n=8 mice per group. *P<0.05 vs. control and vehicle. Panel B. IQ-1S treatment decreases neurological deficit. Mice were treated with IQ-1S (i.p., 25 mg/kg) or with vehicle control (10% solutol), 30 minutes before and 24 hours after MCAO or without any treatment (control). Mice were examined for neurological deficits after 48 hours of reperfusion using a 4-point scale, as described (see Methods). n=8 mice per group.

3.3. Computation of blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability of IQ-1S

Although NO has a good permeability via the BBB, intact IQ-1S is necessary for JNK inhibition in brain tissue. We used a modern machine learning algorithm to predict the BBB permeability-surface area (PS) product (logPS) [41] from physical-chemical descriptors [48]. The descriptors were calculated for the neutral form of IQ-1S (see Methods) [46]. The values of aLogP and tPSA were found to be 2.91 and 57.31, respectively. Using these descriptors, together with number of rotatable bonds (Nrot=1) for this molecule and implementation of classification and regression trees, we predict that IQ-1S has strong (CNSp+) BBB permeation.

4. Discussion

JNKs are involved in many neuropathological signaling events and play key roles in regulation of brain tissue survival [32]. For example, increased activity of JNK signaling pathways was observed after global and focal ischemia (for review [27]), including transient focal cerebral ischemia in rat and mouse brain [24]. A variety of small-molecule JNK inhibitors have been reported to date [30], and some have been shown to exhibit neuroprotective effects in animal models of stroke [9, 16, 22], suggesting that JNK inhibition could be a relevant strategy in the therapy of ischemic insult. For example, the most commonly used JNK inhibitor SP600125 demonstrated neuroprotective potential in various models [57], including cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury after an acute stroke [16, 21, 22, 38]. This JNK inhibitor decreased neuronal apoptosis, infarct volume, and stroke outcome [16, 21, 22, 38]. However, SP600125 is relatively nonspecific, and 13 of 28 tested kinases were inhibited with similar or greater potency as the JNKs [5]. In contrast, IQ-1S is one of most specific small-molecule, non-peptide JNK inhibitors known and does not inhibit other kinases [46] that play roles in ischemic brain pathological events, including glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) [31], phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) [59], and cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk) [40].

Previously, we found that intraperitoneal administration of IQ-1S led to a rapid rise in the serum concentration of this compound, with an AUC0–12h value of 7.4 μM × hr−1 [47]. Here, we calculated that IQ-1S likely has strong BBB permeation and showed that IQ-1S could be enzymatically converted to NO by liver microsomes (in vitro). Additionally, treatment with IQ-1S led to enhanced NO production in vivo. Thus, we suggest that the beneficial effects of IQ-1S on stroke outcome could be a combined result of JNK inhibition by the parent compound in brain tissue, as well as NO generation during its bioconversion.

JNK exacerbates stroke injury by provoking pro-inflammatory cellular signaling and ischemic cell death [13, 36, 53]. For example, high expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), was recently found in a model of focal cerebral ischemia injury [19]. Because IQ-1S decreases levels of these cytokines in cultures of monocytes and lymphoid cells and inhibits transcriptional activity of NF-κB/AP-1 [46, 47], this compound could protect against brain reperfusion injury via inhibition of the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Moreover, we recently found that IQ-1S can inhibit expression of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-1 and −3 in cultured fibroblast-like synoviocytes [46], and MMPs are known to cause neurovascular damage during early times after stroke injury [8]. Indeed, significant increases in MMP-1, −2, −9, −10, and −13 levels were observed during the acute stage of reperfusion following transient focal cerebral ischemia in mice [33]. Clearly, further work is important to evaluate additional JNK-dependent mechanisms involved in therapeutic effects of IQ-1S after focal ischemia.

While IQ-1S is a specific JNK inhibitor, we found here that its enzymatic bioconversion led to NO generation. There is a growing body of evidence that synthetic NO donors have efficacy in animal models of cerebral ischemia. For example, intraperitoneal injection of NO donor Rut-bpy prior to ischemia/reperfusion reduced brain infarct zone and improved viability of hippocampal neurons [7]. Another NO donor, NOC-18, protected brain mitochondria against ischemia-induced dysfunction [2]. Although the exact mechanisms of NO-induced protection against brain ischemic injuries are not yet clear, NO is known to inhibit the NF-κB pathway in endothelial cells [54]. Similarly, exogenous NO donors attenuated the S-nitrosylation of mixed lineage kinase 3 (MLK3) induced by reperfusion and inhibited activation of the JNK pathway [26]. It should be noted that NO donors could modulate BBB permeability [55], and many attempts have been made to capitalize on this NO mechanism to enhance drug delivery across the BBB [49]. Thus, we suggest that the dual functionality of IQ-1S could thereby potentially enhance neuroprotective activity of this compound during early times after ischemia and reperfusion.

In conclusion, we show here that IQ-1S protects against damage in a mouse model of cerebral reperfusion injury when administered before and during the reperfusion period. We also show that this compound exhibits NO donor activity, which together with previously reported JNK inhibitory activity may contribute to its protective effects. In addition, the known inhibitory effects of IQ-1S on inflammatory cytokine and MMP expression may also contribute to the beneficial therapeutic effects of this compound. Thus, future studies on the relative contributions of vascular and inflammatory mechanisms to the protection by this compound are warranted. In future studies, it will be also interesting to determine whether IQ-1S has a beneficial effect given either in a prophylactic manner, prior to induction of an ischemia, or as a therapeutic agent given during ischemia and reperfusion.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by American Heart Association Grant-in-Aid (13GRNT16930060), NIH IDeA Program Grant GM110732 (M.T.Q.), an equipment grant from the M.J. Murdock Charitable Trust, a United States Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture Hatch project, and the Montana State University Agricultural Experiment Station.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

There are no actual conflicts of interest for the authors.

References

- 1.Andronik-Lion V, Boucher JL, Delaforge M, Henry Y, Mansuy D. Formation of nitric oxide by cytochrome P450-catalyzed oxidation of aromatic amidoximes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;185:452–458. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arandarcikaite O, Jokubka R, Borutaite V. Neuroprotective effects of nitric oxide donor NOC-18 against brain ischemia-induced mitochondrial damages: role of PKG and PKC. Neurosci Lett. 2015;586:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atochin DN, Murciano JC, Gursoy-Ozdemir Y, Krasik T, Noda F, Ayata C, Dunn AK, Moskowitz MA, Huang PL, Muzykantov VR. Mouse model of microembolic stroke and reperfusion. Stroke. 2004;35:2177–2182. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000137412.35700.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atochin DN, Wang A, Liu VW, Critchlow JD, Dantas AP, Looft-Wilson R, Murata T, Salomone S, Shin HK, Ayata C, Moskowitz MA, Michel T, Sessa WC, Huang PL. The phosphorylation state of eNOS modulates vascular reactivity and outcome of cerebral ischemia in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1961–1967. doi: 10.1172/JCI29877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bain J, McLauchlan H, Elliott M, Cohen P. The specificities of protein kinase inhibitors: an update. Biochem J. 2003;371:199–204. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brecht S, Kirchhof R, Chromik A, Willesen M, Nicolaus T, Raivich G, Wessig J, Waetzig V, Goetz M, Claussen M, Pearse D, Kuan CY, Vaudano E, Behrens A, Wagner E, Flavell RA, Davis RJ, Herdegen T. Specific pathophysiological functions of JNK isoforms in the brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:363–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campelo MW, Oria RB, Lopes LG, Brito GA, Santos AA, Vasconcelos RC, Silva FO, Nobrega BN, Bento-Silva MT, Vasconcelos PR. Preconditioning with a novel metallopharmaceutical NO donor in anesthetized rats subjected to brain ischemia/reperfusion. Neurochem Res. 2012;37:749–758. doi: 10.1007/s11064-011-0669-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Candelario-Jalil E, Yang Y, Rosenberg GA. Diverse roles of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in neuroinflammation and cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience. 2009;158:983–994. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carboni S, Hiver A, Szyndralewiez C, Gaillard P, Gotteland JP, Vitte PA. AS601245 (1,3-benzothiazol-2-yl (2-[[2-(3-pyridinyl) ethyl] amino]-4 pyrimidinyl) acetonitrile): a c-Jun NH2-terminal protein kinase inhibitor with neuroprotective properties. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310:25–32. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.064246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caro AA, Cederbaum AI, Stoyanovsky DA. Oxidation of the ketoxime acetoxime to nitric oxide by oxygen radical-generating systems. Nitric Oxide. 2001;5:413–424. doi: 10.1006/niox.2001.0362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen XM, Chen HS, Xu MJ, Shen JG. Targeting reactive nitrogen species: a promising therapeutic strategy for cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2013;34:67–77. doi: 10.1038/aps.2012.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dantas BP, Ribeiro TP, Assis VL, Furtado FF, Assis KS, Alves JS, Silva TM, Camara CA, Franca-Silva MS, Veras RC, Medeiros IA, Alencar JL, Braga VA. Vasorelaxation induced by a new naphthoquinone-oxime is mediated by NO-sGC-cGMP pathway. Molecules. 2014;19:9773–9785. doi: 10.3390/molecules19079773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis RJ. Signal transduction by the JNK group of MAP kinases. Cell. 2000;103:239–252. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ertl P, Rohde B, Selzer P. Fast calculation of molecular polar surface area as a sum of fragment-based contributions and its application to the prediction of drug transport properties. J Med Chem. 2000;43:3714–3717. doi: 10.1021/jm000942e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fabian RH, Perez-Polo JR, Kent TA. Perivascular nitric oxide and superoxide in neonatal cerebral hypoxia-ischemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H1809–1814. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00301.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao Y, Signore AP, Yin W, Cao G, Yin XM, Sun F, Luo Y, Graham SH, Chen J. Neuroprotection against focal ischemic brain injury by inhibition of c-Jun N-terminal kinase and attenuation of the mitochondrial apoptosis-signaling pathway. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:694–712. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghose AK, Crippen GM. Atomic physicochemical parameters for three-dimensional-structure-directed quantitative structure-activity relationships. 2. Modeling dispersive and hydrophobic interactions. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 1987;27:21–35. doi: 10.1021/ci00053a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glover RE, Corbett JT, Burka LT, Mason RP. In vivo production of nitric oxide after administration of cyclohexanone oxime. Chem Res Toxicol. 1999;12:952–957. doi: 10.1021/tx990058v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gong G, Xiang L, Yuan L, Hu L, Wu W, Cai L, Yin L, Dong H. Protective effect of glycyrrhizin, a direct HMGB1 inhibitor, on focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion-induced inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in rats. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89450. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gu Z, Jiang Q, Zhang G. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase and c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase in ischemic tolerance. Neuroreport. 2001;12:3487–3491. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200111160-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guan QH, Pei DS, Liu XM, Wang XT, Xu TL, Zhang GY. Neuroprotection against ischemic brain injury by SP600125 via suppressing the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways of apoptosis. Brain Res. 2006;1092:36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.03.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guan QH, Pei DS, Zhang QG, Hao ZB, Xu TL, Zhang GY. The neuroprotective action of SP600125, a new inhibitor of JNK, on transient brain ischemia/reperfusion-induced neuronal death in rat hippocampal CA1 via nuclear and non-nuclear pathways. Brain Res. 2005;1035:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gupta S, Barrett T, Whitmarsh AJ, Cavanagh J, Sluss HK, Derijard B, Davis RJ. Selective interaction of JNK protein kinase isoforms with transcription factors. The EMBO journal. 1996;15:2760–2770. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayashi T, Sakai K, Sasaki C, Zhang WR, Warita H, Abe K. c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and JNK interacting protein response in rat brain after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion. Neurosci Lett. 2000;284:195–199. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu BR, Liu CL, Park DJ. Alteration of MAP kinase pathways after transient forebrain ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:1089–1095. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200007000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu SQ, Ye JS, Zong YY, Sun CC, Liu DH, Wu YP, Song T, Zhang GY. S-nitrosylation of mixed lineage kinase 3 contributes to its activation after cerebral ischemia. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:2364–2377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.227124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irving EA, Bamford M. Role of mitogen- and stress-activated kinases in ischemic injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:631–647. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200206000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jaros F, Straka T, Dobesova Z, Pinterova M, Chalupsky K, Kunes J, Entlicher G, Zicha J. Vasorelaxant activity of some oxime derivatives. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;575:122–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson GL, Nakamura K. The c-jun kinase/stress-activated pathway: regulation, function and role in human disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:1341–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koch P, Gehringer M, Laufer SA. Inhibitors of c-Jun N-Terminal Kinases: An Update. J Med Chem. 2015;58:72–95. doi: 10.1021/jm501212r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koh SH, Yoo AR, Chang DI, Hwang SJ, Kim SH. Inhibition of GSK-3 reduces infarct volume and improves neurobehavioral functions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;371:894–899. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuan CY, Whitmarsh AJ, Yang DD, Liao G, Schloemer AJ, Dong C, Bao J, Banasiak KJ, Haddad GG, Flavell RA, Davis RJ, Rakic P. A critical role of neural-specific JNK3 for ischemic apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15184–15189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336254100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lenglet S, Montecucco F, Mach F, Schaller K, Gasche Y, Copin JC. Analysis of the expression of nine secreted matrix metalloproteinases and their endogenous inhibitors in the brain of mice subjected to ischaemic stroke. Thromb Haemost. 2014;112:363–378. doi: 10.1160/TH14-01-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li ST, Pan J, Hua XM, Liu H, Shen S, Liu JF, Li B, Tao BB, Ge XL, Wang XH, Shi JH, Wang XQ. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase protects neurons against ischemic injury through regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2014;20:154–164. doi: 10.1111/cns.12182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu H, Li J, Zhao F, Wang H, Qu Y, Mu D. Nitric oxide synthase in hypoxic or ischemic brain injury. Rev Neurosci. 2015;26:105–117. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2014-0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Y, Wang D, Wang H, Qu Y, Xiao X, Zhu Y. The protective effect of HET0016 on brain edema and blood-brain barrier dysfunction after cerebral ischemia/reperfusion. Brain Res. 2014;1544:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mehta SL, Manhas N, Raghubir R. Molecular targets in cerebral ischemia for developing novel therapeutics. Brain Res Rev. 2007;54:34–66. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murata Y, Fujiwara N, Seo JH, Yan F, Liu X, Terasaki Y, Luo Y, Arai K, Ji X, Lo EH. Delayed inhibition of c-Jun N-terminal kinase worsens outcomes after focal cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci. 2012;32:8112–8115. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0219-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nijboer CH, van der Kooij MA, van BF, Ohl F, Heijnen CJ, Kavelaars A. Inhibition of the JNK/AP-1 pathway reduces neuronal death and improves behavioral outcome after neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24:812–821. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Osuga H, Osuga S, Wang F, Fetni R, Hogan MJ, Slack RS, Hakim AM, Ikeda JE, Park DS. Cyclin-dependent kinases as a therapeutic target for stroke. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10254–10259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.170144197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pardridge WM. Log(BB), PS products and in silico models of drug brain penetration. Drug Discov Today. 2004;9:392–393. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03065-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pauwels B, Boydens C, Decaluwe K, Van de Voorde J. NO-donating oximes relax corpora cavernosa through mechanisms other than those involved in arterial relaxation. J Sex Med. 2014;11:1664–1674. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pearson BD. Indenoquinolines. III. Derivatives of 11H-Indeno-[1,2-b]quinoxaline and related indenoquinolines. J Org Chem. 1962;27:1674–1678. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pei DS, Song YJ, Yu HM, Hu WW, Du Y, Zhang GY. Exogenous nitric oxide negatively regulates c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation via inhibiting endogenous NO-induced S-nitrosylation during cerebral ischemia and reperfusion in rat hippocampus. J Neurochem. 2008;106:1952–1963. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qi SH, Hao LY, Yue J, Zong YY, Zhang GY. Exogenous nitric oxide negatively regulates the S-nitrosylation p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation during cerebral ischaemia and reperfusion. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2013;39:284–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2012.01284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schepetkin IA, Kirpotina LN, Hammaker D, Kochetkova I, Khlebnikov AI, Lyakhov SA, Firestein GS, Quinn MT. Anti-Inflammatory Effects and Joint Protection in Collagen-induced Arthritis Following Treatment with IQ-1S, a Selective c-Jun N-terminal Kinase Inhibitor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015;353:505–516. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.220251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schepetkin IA, Kirpotina LN, Khlebnikov AI, Hanks TS, Kochetkova I, Pascual DW, Jutila MA, Quinn MT. Identification and characterization of a novel class of c-Jun N-terminal kinase inhibitors. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;81:832–845. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.077446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suenderhauf C, Hammann F, Huwyler J. Computational prediction of blood-brain barrier permeability using decision tree induction. Molecules. 2012;17:10429–10445. doi: 10.3390/molecules170910429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thiel VE, Audus KL. Nitric oxide and blood-brain barrier integrity. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2001;3:273–278. doi: 10.1089/152308601300185223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tian H, Zhang QG, Zhu GX, Pei DS, Guan QH, Zhang GY. Activation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase 3 is mediated by the GluR6.PSD-95.MLK3 signaling module following cerebral ischemia in rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 2005;1061:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vassalli G, Milano G, Moccetti T. Role of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases in Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury during Heart Transplantation. Journal of transplantation. 2012;2012:928954. doi: 10.1155/2012/928954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Veras RC, Rodrigues KG, do Alustau MC, Araujo IG, de Barros AL, Alves RJ, Nakao LS, Braga VA, Silva DF, de Medeiros IA. Participation of nitric oxide pathway in the relaxation response induced by E-cinnamaldehyde oxime in superior mesenteric artery isolated from rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2013;62:58–66. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31829013ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vosler PS, Graham SH, Wechsler LR, Chen J. Mitochondrial targets for stroke: focusing basic science research toward development of clinically translatable therapeutics. Stroke. 2009;40:3149–3155. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.543769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Waldow T, Witt W, Weber E, Matschke K. Nitric oxide donor-induced persistent inhibition of cell adhesion protein expression and NFkappaB activation in endothelial cells. Nitric Oxide. 2006;15:103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Winter S, Konter J, Scheler S, Lehmann J, Fahr A. Permeability changes in response to NONOate and NONOate prodrug derived nitric oxide in a blood-brain barrier model formed by primary porcine endothelial cells. Nitric Oxide. 2008;18:229–239. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yamasaki T, Kawasaki H, Nishina H. Diverse Roles of JNK and MKK Pathways in the Brain. Journal of signal transduction. 2012;2012:459265. doi: 10.1155/2012/459265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yeste-Velasco M, Folch J, Casadesus G, Smith MA, Pallas M, Camins A. Neuroprotection by c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase inhibitor SP600125 against potassium deprivation-induced apoptosis involves the Akt pathway and inhibition of cell cycle reentry. Neuroscience. 2009;159:1135–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yu HM, Xu J, Li C, Zhou C, Zhang F, Han D, Zhang GY. Coupling between neuronal nitric oxide synthase and glutamate receptor 6-mediated c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling pathway via S-nitrosylation contributes to ischemia neuronal death. Neuroscience. 2008;155:1120–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zheng Y, Hou J, Liu J, Yao M, Li L, Zhang B, Zhu H, Wang Z. Inhibition of autophagy contributes to melatonin-mediated neuroprotection against transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats. J Pharmacol Sci. 2014;124:354–364. doi: 10.1254/jphs.13220fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]