Abstract

We present a case of cryptococcosis with adrenal insufficiency and meningitis in a healthy host without any risk factors. Antifungal therapy did not reduce the cryptococcal antigen titers of the cerebrospinal fluid and serum or the bilateral adrenal gland enlargement. It was suggested that the adrenal glands were the focus of persistent fungemia. Removal of both adrenal glands brought about a response to antifungal therapy. We conclude that if antifungal therapy is ineffective, bilateral adrenalectomy is an effective measure for treatment of such patients. Cryptococcosis is a possible cause of primary adrenal insufficiency in immunocompetent patients.

Keywords: Primary adrenal insufficiency, Cryptococcus spp., fungemia, meningitis, immunocompetent, adrenalectomy

Introduction

Adrenal insufficiency is a disorder characterized by hypoactive adrenal glands, resulting in insufficient production of cortisol and aldosterone by the adrenal cortex. This disorder may develop due to primary failure of the adrenal cortex or secondary to an abnormality of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis (1-3). Patients with adrenal insufficiency often present with fatigue, weight loss, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, low blood pressure, and skin pigmentation. Primary adrenal insufficiency may be caused by autoimmune disease, infectious diseases, metastatic tumors, adrenal hemorrhaging or infarction, and pharmaceuticals. A variety of agents can infect the adrenal glands, leading to adrenal insufficiency. Disseminated tuberculosis, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and disseminated fungal infections are the major infectious causes. In most cases, tuberculosis is the main cause of primary adrenal insufficiency (2,3). However, cryptococcosis is also a possible cause, as seen in our case. This finding suggests that cryptococcosis should be borne in mind as a possible cause of primary adrenal insufficiency.

Cryptococcosis is a serious fungal disease with a higher morbidity and mortality than other fungal diseases (4-8). Meningitis or cryptococcal lung disease is the most common manifestation of cryptococcosis, as it rarely affects the adrenal glands; the infection is also more common in immunocompromised patients than in immunocompetent ones (4-8). Indeed, few reports exist of immunocompetent patients suffering from disseminated cryptococcosis (9-13).

Although adrenal gland involvement during cryptococcosis has been previously reported in immunocompetent patients (9-13), some cases have included diabetes mellitus, which increases a patient's susceptibility to infection.

We herein report the case of an immunocompetent patient with cryptococcal adrenal insufficiency and meningitis. In this patient, the surgical removal of the adrenal glands, which were thought to be a focus of the fungemia, led to successful treatment. To our knowledge, this is the first report of Cryptococcus spp. affecting both adrenal glands with meningitis and lung masses in an immunocompetent patient who had no other risk factors.

Case Report

A 49-year-old Japanese man had been in good health until 2 months prior to admission to the Japan Self Defense Forces Central Hospital, Tokyo, Japan, in July 2014. During those two months, he developed anorexia, weight loss, and increased skin pigmentation.

A physical examination at the time of admission revealed a dehydrated man with generalized pigmentation and hepatic enlargement without any skin changes, chest symptoms, or a stiff neck. He was 174 cm tall and weighed 66 kg. His blood pressure was 93/57 mmHg; pulse rate, 109 beats per minute; and temperature, 36.7°C. His other vital signs were normal. A neurological examination revealed no focal or lateralizing deficits.

The laboratory data on admission were as follows: sodium, 132 mEq/L; potassium, 5.6 mEq/L; chloride, 92 mEq/L; creatinine, 1.57 mg/dL; and urea nitrogen, 36 mg/dL. The BUN/creatinine ratio was 22, which suggested possible dehydration. His white blood cell count, hematocrit, liver function tests, albumin, total protein, calcium, and inorganic phosphate values were normal (Table 1). The plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) level and plasma renin activity (PRA) were elevated at 707.5 pg/mL (normal <63.3 pg/mL) and 51.3 ng/mL/h (normal <4.0 ng/mL/h), respectively. The plasma cortisol and plasma aldosterone levels were both lower than normal at 2.9 μg/dL (normal <21.1 μg/dL) and 3.5 ng/dL (normal <24.0 ng/mL). The tentative diagnosis on admission was adrenal gland insufficiency (Table 1).

Table 1.

Laboratory Findings at Admission.

| Na | 132 | (mEq/dL) | WBC | 6,900 | (/μL) | IgA | 137 | (mg/dL) |

| K | 3.6 | (mEq/dL) | Seg | 52.5 | % | IgM | 1,290 | (mg/dL) |

| Cl | 92 | (mEq/dL) | Lym | 40.0 | % | C3 | 166 | (mg/dL) |

| BUN | 36 | (mg/dL) | Mon | 5.4 | % | C4 | 36 | (mg/dL) |

| Cre | 1.57 | (mg/dL) | Eos | 1.7 | % | ACTH | 707.5 | (pg/dL) |

| AST | 22 | (IU/L) | Bas | 0.4 | % | Cortisol | 2.9 | (µg/dL) |

| ALT | 21 | (IU/L) | Hb | 15.6 | (g/dL) | PRA | 5.3 | (ng/mL/h) |

| LDH | 128 | (IU/L) | Plt | 27.0 | (×104/μL) | Aldosterone | 3.5 | (ng/mL) |

| CRP | 3.48 | (mg/dL) | IgG | 822 | (mg/dL) |

Reference values: PRA 0.2-4.0 ng/mL/h, Aldosterone 3-24 ng/mL, ACTH 7.2-63.3 pg/dL, Cortisol: 4.0-21.1 µg/dL

Further examinations were performed to differentiate primary adrenal insufficiency from secondary adrenocortical insufficiency. An ACTH stimulation test (250 μg of intramuscular cosyntropin), which measures the response of the adrenal glands to adrenocorticotropic hormone, failed to induce a rise in the serum or urinary cortisol levels. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head demonstrated normal findings. No pituitary tumor was detected.

A diagnosis of primary adrenocortical insufficiency was made, and the patient was started on a daily dose of 15 mg hydrocortisone, according to the treatment for adrenal insufficiency (2). Additional tests were performed to determine whether his primary adrenal insufficiency was caused by an autoimmune disorder, tuberculosis, or metastasis of a malignant tumor. The QuantiFERON-TB Gold test (QIAGEN, Osaka, Japan) for tuberculosis was negative.

An abdominal ultrasonography showed bilateral adrenal enlargement, with the glands measuring approximately 55×33×14 mm (left side) and 56×25×49 mm (right side). No calcification was seen on either adrenal gland (Fig. 1). A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen also demonstrated bilateral adrenal enlargement. Tumors or metastases were not found on a CT or Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) scan. However, the CT scan showed nodular shadows around both lungs (right S1, left S1+2, left S6) (Fig. 2). The nodules were 9, 3, and 8 mm in diameter. The serum anti-nuclear antibody, anti-ds DNA antibodies, C3, C4, and rheumatoid factor, β-D-glucan levels were all within the normal range.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography image of the adrenal mass from the patient. Bilateral adrenal enlargement is seen in the contrast-enhanced computed tomography (arrows). An enhancing effect is seen at the margin and inside the adrenal mass. No calcification is seen in the mass.

Figure 2.

Computed tomography image of the lung nodules from the patient. The right S1, left S1+2, and left S6 nodules were 9, 3, and 8 mm in diameter, respectively.

Based on this evidence, tuberculosis, collagen diseases, and metastasizing tumors were excluded from the possible diagnosis. Subsequently, a CT-guided biopsy of the right adrenal gland was performed to obtain tissue for culture and a histologic evaluation. Cryptococcus spp. were identified within the necrotic adrenal tissue (Fig. 3). The tissue fragments were cultured for bacteria, fungi, and acid-fast organisms. None of the cultures yielded any growth. The adrenal gland cytology was class II.

Figure 3.

Histologic studies of the right adrenal gland by a fine-needle aspiration biopsy (periodic acid-Schiff stain ×100). Cryptococcosis is stained with the periodic acid-Schiff stain.

Ultimately, a diagnosis of primary adrenal insufficiency due to a cryptococcal infection was reached. Lumbar puncture yielded colorless cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) with a leukocyte count of 151/mm3. The CSF protein level was elevated to 72.3 mg/dL with a concurrent serum glucose level of 30 mg/dL. These findings suggested meningitis; Cryptococcus spp. were seen in the CSF on a smear culture (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

A cytological analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid (Grocott’s stain ×800). Yeast-like fungi are seen in the histological analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid.

Nevertheless, a culture of the CSF revealed no growth of Cryptococcus spp., and the CSF and serum cryptococcal antigen titers were 1:8 and 1:4,096, respectively. Bronchial lavage fluid and sputum cultures for fungus were negative. We strongly suspected that this patient was suffering from disseminated cryptococcosis, which causes primary adrenal insufficiency and meningitis. Therefore, we evaluated the patient's immunological status. The results revealed that the serum IgG level was 822 mg/dL, IgM was 1,290 mg/dL, C3 was 166 mg/dL, and C4 was 36 mg/dL. Antibodies for HIV were not detected on either of two separate examinations approximately two months apart. The CD4 count was 1,324 cells/mm3. Additionally, a bone marrow aspiration sample showed a normal distribution with no amplifier plasma cells and an IgM level below 1,500 mg/dL, which led us to conclude that the patient was not immunocompromised. Based on the diagnosis of cryptococcal infection, intravenous liposomal amphotericin B (300 mg daily) and oral flucytosine (7,000 mg daily) were administered.

After five days of therapy, the combination of liposomal amphotericin B and flucytosine was discontinued because liposomal amphotericin B had an adverse effect on the patient's renal function. We started hydration and restarted the combination of intravenous liposomal amphotericin B and oral flucytosine at a daily dose of 200 mg and 6,000 mg, respectively. After two weeks of therapy, consolidation therapy was started with oral fluconazole at 800 mg daily. He was treated for 5 months, at the end of which his medication dosages were fluconazole, 11.2 g; amphotericin B, 3,600 mg; and flucystosine, 126 g in total. However, the serum cryptococcal antigen titers did not decrease, and the patient's symptoms did not improve. A repeat abdominal CT scan showed that the adrenal enlargement was unchanged.

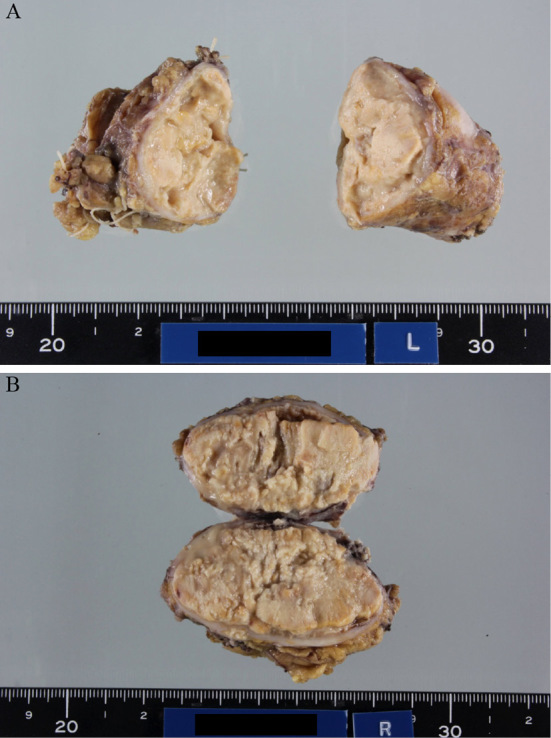

Due to the ineffectiveness of the therapy and the patient's deteriorated condition, bilateral adrenalectomy was performed. The glands were approximately 7.5×4.5×4.5 cm (left side) and 6.5×4.0×4.0 cm (right side) (Fig. 5). A histological analysis of the resected adrenal glands showed massive noncaseating necrosis containing yeast-like particles, which was diagnostic for a Cryptococcus spp. infection (Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

Gross appearance of the adrenal glands. (A) Left side (approximately 7.5×4.5×4.5 cm). (B) Right side (approximately 6.5×4.0×4.0 cm)

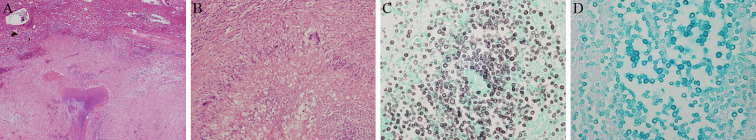

Figure 6.

Adrenal histopathology. (A) Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining ×40. (B) H&E staining ×200. (C) Grocott’s staining ×800. (D) Alcian blue staining ×800. Widespread necrotizing granulomatous inflammation is seen. Epithelioid granuloma is seen along with lymphocytes, plasma cells, and multinucleated giant cells. The epithelioid granuloma is covered with fibrous connective tissue (A, B). In the necrotic tissue, a large number of class round fungal growths are seen that are stained positive with Grocott’s and Alcian blue staining (C, D).

Oral fluconazole at a dose of 800 mg daily was continued after adrenalectomy. At 10 months after adrenalectomy, the serum cryptococcal antigen titer had decreased to 1:128 (Fig. 7). Repeated lumbar punctures were performed, revealing no detected CSF cryptococcal antigen titer, and a CSF culture revealed no growth of Cryptococcus spp. The patient is currently taking 800 mg of daily oral fluconazole, and he is being followed up every 2-3 months to check for any relapse.

Figure 7.

Time course of the serum cryptococcal titer and CRP.

Discussion

Primary adrenal insufficiency is most likely to occur due to factors such as tuberculosis, HIV, or other infections. However, when trying to determine the differential diagnosis in patients with primary adrenal insufficiency who do not show any evidence of tuberculosis or other potential causes, it is important to keep cryptococcosis in mind, even though cryptococcosis rarely infects the adrenal glands in immunocompetent individuals.

Our patient was HIV-negative and did not have tuberculosis, liver cirrhosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, malignancies, or diabetes mellitus; had not undergone organ transplant; and had no history of contact with bird excrement. Given that chest CT revealed a few nodular shadows, we recommended a CT-guided biopsy to check if these were caused by cryptococcosis. However, the patient refused further evaluations. The bronchoalveolar lavage we performed showed normal findings and an absence of cryptococcosis. Although this case demonstrated high serum IgM and C3 levels, a bone marrow aspiration sample showed a normal distribution with no amplifier plasma cells and an IgM level below 1,500 mg/dL, which led us to conclude that the patient was not immunocompromised.

Serious defects in cell-mediated immune surveillance lead to dissemination. As dissemination occurs, the central nervous system is commonly involved. Although it is unclear how cryptococcosis infects the adrenal glands, and the CD4 count of the current case was within the normal range, we suspect that Cryptococcus spp. spread to the adrenal glands hematogenously, similar to the process in tuberculosis (7). These symptoms of dissemination correspond to the symptoms in our patient.

It is well known that Cryptococcus spp. live in the prostate, particularly in persons who are infected with HIV. However, the patient's prostate examination did not show any bogginess or tenderness, and his urine cultures were negative for Cryptococcus spp. On comparing the findings in our patient with previously reported cases of adrenal insufficiency with cryptococcal infections, we noted several differences. The available reports have been summarized in Table 2 (9-13). We compared each case with respect to the systemic condition, complications, surgery, and environmental factors, especially contact with birds. To our knowledge, this is the first report of cryptococcosis of both adrenal glands with systemic conditions such as meningitis and lung masses in an immunocompetent patient who had no history of contact with birds or diabetes mellitus (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of Prior Cases with Our Case.

| (11) | (9) | (10) | (12) | (13) | Ito et al. (Present study) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic conditions | liver mass | meningitis | meningitis | - | lung mass | lung mass, meningitis |

| Complications | DM | - | DM | - | DM | - |

| Surgery | unilateral | bilateral | bilateral | - | - | bilateral |

| Environment | bird | bird | unknown | unknown | - | - |

DM: diabetes mellitus

The initial therapy for cryptococcosis is liposomal amphotericin B plus flucytosine, followed by fluconazole (5). In refractory cases, bilateral adrenalectomy has been effective for controlling cryptococcal infections (9,10,13). The use of steroids before the diagnosis of cryptococcosis and an insufficient dose of antifungal drugs due to side effects may have contributed to making this case refractory to treatment. In our case, antifungal therapy did not reduce the size of the adrenal glands, nor did it normalize the serum cryptococcal antigen titers. In addition, our patient was revealed to have cryptococcal meningitis. Untreated cryptococcosis of the central nervous system (CNS) is fatal even if the patient is immunocompetent (6-8). We therefore decided to perform bilateral adrenalectomy.

Unilateral adrenalectomy can be considered if the patient carries a risk of bleeding. Matsuda et al. reported that, despite the presence of bilateral adrenal masses in their patient, they chose to perform unilateral adrenalectomy because adhesion of the right adrenal mass to the liver was anticipated, which may have caused massive bleeding. Unilateral adrenalectomy led to remarkable decreases in the serum cryptococcal antigen titers and a reduction in the size of the remaining right adrenal mass (11). If the masses in the adrenal gland or liver start to become enlarged or the Cryptococcus antigen titer is elevated, unilateral adrenalectomy should be considered. In our case, the serum cryptococcal antigen titers began to decrease seven months after bilateral adrenalectomy (Fig. 7). A close association between his adrenal and meningeal involvement was thus apparent. Accordingly, hormone replacement therapy was mandatory due to the lack of hormone production after adrenalectomy (2,3).

Cryptococcosis commonly affects the lungs and CNS, particularly in patients with HIV infection. Although less frequent, cryptococcal infection also occurs in HIV-negative patients, including those with liver cirrhosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, malignancies, and diabetes mellitus, as well as in organ transplant recipients.

We treated a rare case of cryptococcosis with adrenal insufficiency and meningitis in an immunocompetent patient who did not have any risk factors, such as liver cirrhosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, malignancies, diabetes mellitus, organ transplant, or a history of contact with birds. Despite being initially refractory to antifungal therapy, the patient responded well to treatment after bilateral adrenalectomy. This case stresses the importance of keeping cryptococcosis in mind as a differential diagnosis in immunocompetent patients with primary adrenal insufficiency.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1.Paolo WF Jr, Nosanchuk JD. Adrenal infections. Int J Infect Dis 10: 343-353, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koetz K, Kienitz T, Quinkler M. Management of steroid replacement in adrenal insufficiency. Minerva Endocrinol 35: 61-72, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charmandari E, Nicolaides NC, Chrousos GP. Adrenal insufficiency. Lancet 383: 2152-2167, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kronstad JW, Attarian R, Cadieux B, et al. . Expanding fungal pathogenesis: Cryptococcus breaks out of the opportunistic box. Nat Rev Microbiol 9: 193-203, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saag MS, Graybill RJ, Larsen RA, et al. . Practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 30: 710-718, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bicanic T, Harrison TS. Cryptococcal meningitis. Br Med Bull 72: 99-118, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Subramanian S, Mathai D. Clinical manifestations and management of cryptococcal infection. J Postgrad Med 51 Suppl 1: S21-S26, 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Horst CM, Saag MS, Cloud GA, et al. . Treatment of cryptococcal meningitis associated with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group and AIDS Clinical Trials Group. N Engl J Med 337: 15-21, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takeshita A, Nakazawa H, Akiyama H, et al. . Disseminated cryptococcosis presenting with adrenal insufficiency and meningitis: resistant to prolonged antifungal therapy but responding to bilateral adrenalectomy. Intern Med 31: 1401-1405, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawamura M, Miyazaki S, Mashiko S, et al. . Disseminated cryptococcosis associated with adrenal masses and insufficiency. Am J Med Sci 316: 60-64, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuda Y, Kawate H, Okishige Y, et al. . Successful management of cryptococcosis of the bilateral adrenal glands and liver by unilateral adrenalectomy with antifungal agents: a case report. BMC Infect Dis 11: 340, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hung ZS, Lai YH, Hsu YH, Wang CH, Fang TC, Hsu BG. Disseminated cryptococcosis causes adrenal insufficiency in an immunocompetent individual. Intern Med 49: 1023-1026, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ranjan P, Jana M, Krishnan S, Nath D, Sood R. Disseminated cryptococcosis with adrenal and lung involvement in an immunocompetent patient. J Clin Diagn Res 9: OD04-OD05, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]