Abstract

Cold stress is very detrimental to crop production. However, only a few genes in rice have been identified with known functions related to cold tolerance. To meet this agronomic challenge more effectively, researchers must take global approaches to select useful candidate genes and find the major regulatory factors. We used five Gene expression omnibus series data series of Affymetrix array data, produced with cold stress-treated samples from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), and identified 502 cold-inducible genes common to both japonica and indica rice cultivars. From them, we confirmed that the expression of two randomly chosen genes was increased by cold stress in planta. In addition, overexpression of OsWRKY71 enhanced cold tolerance in ‘Dongjin,’ the tested japonica cultivar. Comparisons between japonica and indica rice, based on calculations of plant survival rates and chlorophyll fluorescence, confirmed that the japonica rice was more cold-tolerant. Gene Ontology enrichment analysis indicate that the ‘L-phenylalanine catabolic process,’ within the Biological Process category, was the most highly overrepresented under cold-stress conditions, implying its significance in that response in rice. MapMan analysis classified ‘Major Metabolic’ processes and ‘Regulatory Gene Modules’ as two other major determinants of the cold-stress response and suggested several key cis-regulatory elements. Based on these results, we proposed a model that includes a pathway for cold stress-responsive signaling. Results from our functional analysis of the main signal transduction and transcription regulation factors identified in that pathway will provide insight into novel regulatory metabolism(s), as well as a foundation by which we can develop crop plants with enhanced cold tolerance.

Keywords: abiotic stress, cold stress, MapMan analysis, meta-expression analysis, Gene Ontology enrichment analysis, transcriptomics, rice, microarray

Introduction

Agronomic productivity is declining due to various environmental problems, including cold stress. Crop yields are not sustainable when threatened by either chilling or freezing. The typical physiological response of a rice (Oryza sativa) plant exposed to such conditions is inhibited germination, followed by retarded seedling growth and restricted photosynthesis. Long periods of stress lead to chlorosis and tissue necrosis. Therefore, it is important that researchers improve their understanding of the regulatory mechanisms that can enhance cold tolerance.

The process of stress responses comprises perception of the low temperature, signal transduction, activation of TFs and stress-responsive genes, detoxification of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and initiation of repair systems. These steps make plants more tolerant to cold stress. Genetic and molecular studies have elucidated the functions of 59 such genes, for which information is now well-summarized in the OGRO database1 (Yamamoto et al., 2012). Many important crops, including rice, are sensitive to low temperatures and do not easily acclimatize during periods of cold stress. At the seedling stage, rice is more vulnerable, even to mild chilling. This can reduce overall growth and disrupt and delay the cycle of crop maturation, eventually decreasing yields (Zhang et al., 2014). The challenge of global warming means that crop plants, including rice, will be more exposed to extreme growing environments, e.g., low and high temperatures. Although the response by rice to cold stress has been described (Zhi-guo et al., 2014; Wang D. et al., 2016; Shakiba et al., 2017), we still need to identify more effective genes that can regulate this response.

Transcriptome analysis is a very powerful tool that provides the global view of a phenomenon and frequently suggests novel candidate genes for further study. Such analyses have been conducted to improve our understanding about the cold-stress response in rice. For example, (Zhang T. et al., 2012) have found more than 500 candidate genes that are significantly up-regulated under low temperatures. Moreover, 183 DEGs related to cold stress have been identified by Chawade et al. (2013), 383 DEGs by Yang et al. (2015), and more than 2000 DEGs by Zhao et al. (2014). Nevertheless, it has been difficult to determine from publicly available transcriptome data which of these candidate genes show consistent expression patterns under stress as well as across a range of cultivars.

Here, we focused on genes that are consistently up-regulated between japonica and indica cultivars under cold stress at the seedling stage. Our investigation utilized a large set of transcriptome data consisting of 27 japonica and 36 indica comparisons under low-temperature conditions, as obtained from the NCBI GEO (Barrett et al., 2011). From this, we identified 502 candidate genes that we further analyzed for their biological significance using GO term enrichment analysis and functional classifications via MapMan analysis2. We also selected two genes and confirmed their cold-inducible expression patterns using promoter-GUS trap systems. Based on those results, we proposed a novel promoter for further research applications to enhance cold tolerance. We then developed a hypothetical model to describe the signaling and transcriptional regulatory pathways that process the response to cold stress in rice.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Stress Treatments

Plants of japonica rice cv. Dongjin (‘DJ’) and indica rice ‘IR64’ (‘IR64’) were grown in a walk-in chamber (Koencon, Hanam, South Korea) under conditions of 30°C [200 μmol m-2 s-1 (day)]/22°C (night) and a 12-h photoperiod for 10 days in plastic boxes containing 100 g of soil used in growing rice (Punong, Kyung-Ju, Korea) (Kumar et al., 2017). The effects of cold stress (exposure at 4°C) on the light intensity 110 μmol m-2 s-1 were examined after exposure to cold stress for 0, 24 h/1 day, 48 h/2 days, 72 h/3 days, 96 h/4 days, 120 h/5 days, and 144 h/6 days using chlorophyll fluorescence. Our mock treatment comprised a group of plants that remained at the normal growing temperature (28°C) throughout the experimental period. To observe the physiological features of these seedlings, we used samples collected before cold stress was induced, as well as from plants after 4 days of stress, and then after recovery under normal conditions for 5 days. Fresh weights (FWs) were recorded after recovery from cold stress, and dry weights (DWs) were measured after the samples were dried at 80°C for 2 days.

RT and qRT-PCR Analysis

For monitoring the expression of cold-inducible marker genes, seedlings (selected at 10 DAG, or 10 DAG) were hydroponically cultured in Yoshida solution and exposed to 4°C for 0, 1, 3, 6, 12, or 24 h. Primers of OsZFP182/LOC_Os03g60560 and OsWYRKY71/LOC_Os02g08440 were used for RT and qRT-PCR analyses at a final concentration of 10 pmol, with 3 μL (equivalent to 30 ng of total RNA) of cDNA as template (Supplementary Table S1). The internal controls were primers of rice ubiquitin 5 (OsUbi5) and rice actin 1 (RAc1) (Supplementary Table S1). An RNeasy Mini Plant Kit (Qiagen, Germany) was used for total RNA isolation and an RT Complete Kit (Biofact, Korea) was used for cDNA synthesis according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Primers were designed with Gene Runner software3 and NCBI primer blast4. The amplified products were resolved on a 1% agarose gel.

Measurement of H2O2

An uptake assay was conducted to determine the relative concentration of H2O2, using Amplex® Red reagent (10-acetyle-3, 7dihydroxyphenoxazine; Molecular Probes/Invitrogen, United States) (Mohanty et al., 1997). Leaf tissues (0.1 mg μL-1) were homogenized in a standard MS medium (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) and then incubated under darkness for 30 min with horseradish peroxidase (0.2 U mL-1) and Amplex® Red reagent (1 μM). The H2O2 released from these tissues was detected by a SpectraMax 250 Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices Inc., United States) with absorbance measured at 560 nm (Kumar et al., 2014).

Meta-Expression Analysis

We downloaded raw data for five GSE data series (i.e., GEO accession number GSE6901, GSE33204, GSE37940, GSE38023, and GSE31077) that are related to cold-stress responses, as indicated from the NCBI GEO5 (Barrett et al., 2011). Details are presented in Supplementary Table S2. The data were normalized using an Affy Package encoded by R language, and the intensity values were transformed into the log2 scale as we have previously described (Cao et al., 2012). This allowed us to generate log2 fold-change values for cold-stressed samples. Similar fold-changes were revealed for other stress conditions. For each data series, we used those fold-change data to perform a KMC analysis to identify genes that were consistently up-regulated under all cold-stress conditions. The KMC analysis of meta-expression data for abiotic stresses – salt, drought, cold, heat, submergence, and anaerobic conditions – grouped all of the candidate genes into 12 clusters. From these, we selected 502 genes that were up-regulated by cold-stress treatment but not during the recovery period. Heatmap images were produced using Mev software (Chu et al., 2008).

GUS Assays and Co-segregation Test of Promoter Trap Lines

To examine GUS expression patterns, we germinated seeds from two promoter trap lines in an MS medium for 7 days. These lines were obtained from a mixed pool of PFG T-DNA tagging lines from POSTECH in Korea (Lee et al., 2004; Jung et al., 2005, 2006, 2015; Hong et al., 2017; Wei et al., 2017). The resultant plantlets were then exposed to cold stress (4°C) for 0 or 24 h. Afterward, whole seedlings from all treatment groups were soaked for 8 h in a GUS-staining solution before their roots were photographed with a camera (Canon EOS 550D; Cannon, Tokyo, Japan).

Analysis of Cis-Regulatory Elements

To identify any consensus CREs in the promoters of our cold-inducible genes, we extracted 2-kb upstream sequences of ATG for LOC_Os01g31370 and LOC_Os03g49830, which were validated in our current GUS assays. We also used the sequence for LOC_Os10g41200, which was previously reported to be a cold-inducible promoter based on the promoter-GUS system (Rerksiri et al., 2013; Jeong and Jung, 2015) from PLANTPAN6 (Chang et al., 2008). Several MEME searches were performed with those sequences in the FASTA format via the Web server hosted by the National Biomedical Computation Resource7. We looked for up to five CREs with an option of 12 maximum motif widths. Using the MAST, we then searched DNA sequences for matches to the putative TOMTOM within a set of promoter sequences (Bailey et al., 2006).

Analysis of Gene Ontology Enrichment

To analyze the biological significance of selected candidate genes, we employed the GO enrichment tool installed in the Rice Oligonucleotide Array Database8 (Jung et al., 2008a; Cao et al., 2012). For this, we uploaded 502 genes showing upregulation in both japonica and indica cultivars under cold stress. A fold-enrichment value higher than the standard (‘1’) meant that the selected GO term was over-represented more than was expected. Terms with >2-fold enrichment values and p-values < 0.05 were also used as criteria for choosing the most significant GO terms in the ‘Biological Process’ category.

MapMan Analysis

The rice MapMan classification system covers 36 BINs, each of which can be extended in a hierarchical manner into subBINs (Usadel et al., 2005; Urbanczyk-Wochniak et al., 2006). By applying diverse MapMan tools, a significant gene list selected from high-throughput data analysis can be integrated to diverse overviews. Here, we uploaded locus IDs from the RGAP for 502 DEGs with a value of ‘3,’ which indicated upregulation under cold stress. Finally, we used four overviews – Metabolism, Regulation, Transcription, and Proteasome – installed in the MapMan toolkit.

Analysis of Rice Genes with Known Functions

To evaluate the functional significance of our candidate genes, we compared our list with the one from OGRO, which summarizes rice genes with known functions (Table 1; Yamamoto et al., 2012).

Table 1.

Rice genes functionally characterized as cold-inducible.

| Gene | Major_F | Minor_F | RAP-DB_ID | MSU_ID | Method | Detailed functions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OsDREB1C | R/T | Cold T | Os06g0127100 | LOC_Os06g03670.1 | OX | Cold, drought, and salinity T. | Ito et al., 2006 |

| ZFP182 | R/T | Cold T | Os03g0820300 | LOC_Os03g60560.1 | OX | Cold, drought, and salinity T. | Huang et al., 2012 |

| OsDREB1B | R/T | Cold T | Os09g0522000 | LOC_Os09g35010.1 | OX | Cold, drought, and salinity T. | Ito et al., 2006 |

| OsDREB1A | R/T | Cold T | Os09g0522200 | LOC_Os09g35030.1 | OX | Cold, drought, and salinity T. | Ito et al., 2006 |

| OsWRKY45 | R/T | Cold T | Os05g0322900 | LOC_Os05g25770.1 | Kd OX | Cold, drought, and salinity T; ABA sensitivity. | Tao et al., 2011 |

| OsWRKY71 | R/T | Cold T | Os02g0181300 | LOC_Os02g08440.1 | OX | Cold T | Kim et al., 2016 |

| OsTPP1 | R/T | Cold T | Os02g0661100 | LOC_Os02g44230.1 | OX | Cold and salinity T. | Ge et al., 2008 |

| OsWRKY76 | R/T | Cold T | Os09g0417600 | LOC_Os09g25060.1 | OX | R to Magnaporthe oryzae; cold T. | Yokotani et al., 2013 |

| OsMYB2 | R/T | Cold T | Os03g0315400 | LOC_Os03g20090.1 | OX | Cold, drought, and salinity T; ABA sensitivity. | Yang et al., 2012 |

| OsCAF1B | R/T | Cold T | Os04g0684900 | LOC_Os04g58810.1 | Others | Cold T | Chou et al., 2014 |

| OsMAPK5 | R/T | Cold T | Os03g0285800 | LOC_Os03g17700.1 | OX | R to Magnaporthe grisea and Burkholderia glumae; cold, drought, and salinity T. | Xiong and Yang, 2003 |

| OsbZIP52/RISBZ5 | R/T | Cold T | Os06g0662200 | LOC_Os06g45140.1 | OX | Cold and drought T. | Liu et al., 2012 |

| OsSPX1 | R/T | Cold T | Os06g0603600 | LOC_Os06g40120.1 | Kd | Cold and oxidative stresses T. | Wang C. et al., 2013 |

| OsDREB1C | R/T | Drought T | Os06g0127100 | LOC_Os06g03670.1 | OX | Cold, drought, and salinity T. | Ito et al., 2006 |

| ZFP182 | R/T | Drought T | Os03g0820300 | LOC_Os03g60560.1 | OX | Cold, drought, and salinity T. | Huang et al., 2012 |

| OsSRO1c | R/T | Drought T | Os03g0230300 | LOC_Os03g12820.1 | Mutant | Stomatal control; oxidative stress R. | You et al., 2013 |

| OsDREB1B | R/T | Drought T | Os09g0522000 | LOC_Os09g35010.1 | OX | Cold, drought, and salinity T. | Ito et al., 2006 |

| OsDREB1A | R/T | Drought T | Os09g0522200 | LOC_Os09g35030.1 | OX | Cold, drought, and salinity T. | Ito et al., 2006 |

| OsWRKY45 | R/T | Drought T | Os05g0322900 | LOC_Os05g25770.1 | Kd OX | Cold, drought, and salinity T; ABA sensitivity. | Tao et al., 2011 |

| OsMYB2 | R/T | Drought T | Os03g0315400 | LOC_Os03g20090.1 | OX | Cold, drought, and salinity T; ABA sensitivity. | Yang et al., 2012 |

| OsbHLH148 | R/T | Drought T | Os03g0741100 | LOC_Os03g53020.1 | OX | Drought T. | Seo et al., 2011 |

| OsCAF1B | R/T | Drought T | Os04g0684900 | LOC_Os04g58810.1 | Others | Drought T | Chou et al., 2014 |

| OsMAPK5 | R/T | Drought T | Os03g0285800 | LOC_Os03g17700.1 | Kd OX | R to Magnaporthe grisea and Burkholderia glumae; cold, drought, and salinity T. | Xiong and Yang, 2003 |

| OsbZIP52/RISBZ5 | R/T | Drought T | Os06g0662200 | LOC_Os06g45140.1 | OX | Cold and drought T. | Liu et al., 2012 |

| ONAC045 | R/T | Drought T | Os11g0127600 | LOC_Os11g03370.1 | OX | Drought and salinity T. | Zheng et al., 2009 |

| OsCDPK7 | R/T | Drought T | Os04g0584600 | LOC_Os04g49510.1 | OX | Drought and salinity T. | Saijo et al., 2000 |

| OsCPK4 | R/T | Drought T | Os02g0126400 | LOC_Os02g03410.1 | Kd | Protection of cellular membrane from drought stress. | Campo et al., 2014 |

| OsERF3 | R/T | Drought T | Os01g0797600 | LOC_Os01g58420.1 | OX | Drought T by controlling ethylene biosynthesis. | Wan et al., 2011 |

| OsAP2-39 | R/T | Drought T | Os04g0610400 | LOC_Os04g52090.1 | OX | Dwarfism; fertility; and drought T. | Yaish et al., 2010 |

| OsDREB1C | R/T | Salinity T | Os06g0127100 | LOC_Os06g03670.1 | OX | Cold, drought, and salinity T. | Ito et al., 2006 |

| OsEATB | R/T | Salinity T | Os09g0457900 | LOC_Os09g28440.1 | OX | Internode elongation; panicle branching; tillering; salinity T. | Qi et al., 2011 |

| ZFP182 | R/T | Salinity T | Os03g0820300 | LOC_Os03g60560.1 | OX | Cold, drought, and salinity T. | Huang et al., 2012 |

| ZFP179 | R/T | Salinity T | Os01g0839100 | LOC_Os01g62190.1 | OX | Salinity and oxidative stress T. | Sun et al., 2010 |

| OsDREB1B | R/T | Salinity T | Os09g0522000 | LOC_Os09g35010.1 | OX | Cold, drought, and salinity T. | Ito et al., 2006 |

| OsDREB1A | R/T | Salinity T | Os09g0522200 | LOC_Os09g35030.1 | OX | Cold, drought, and salinity T. | Ito et al., 2006 |

| OsWRKY45 | R/T | Salinity T | Os05g0322900 | LOC_Os05g25770.1 | Kd OX | Cold, drought, and salinity T; ABA sensitivity. | Tao et al., 2011 |

| OsTPP1 | R/T | Salinity T | Os02g0661100 | LOC_Os02g44230.1 | OX | Cold and salinity T. | Ge et al., 2008 |

| OsMYB2 | R/T | Salinity T | Os03g0315400 | LOC_Os03g20090.1 | OX | Cold, drought, and salinity T; ABA sensitivity. | Yang et al., 2012 |

| OsMAPK5 | R/T | Salinity T | Os03g0285800 | LOC_Os03g17700.1 | Kd OX | R to Magnaporthe grisea and Burkholderia glumae; cold, drought, and salinity T. | Xiong and Yang, 2003 |

| ONAC045 | R/T | Salinity T | Os11g0127600 | LOC_Os11g03370.1 | OX | Drought and salinity T. | Zheng et al., 2009 |

| OsCDPK7 | R/T | Salinity T | Os04g0584600 | LOC_Os04g49510.1 | OX | Drought and salinity T. | Saijo et al., 2000 |

| OsCPK4 | R/T | Salinity T | Os02g0126400 | LOC_Os02g03410.1 | Kd | Protection of cellular membrane from salt stress. | Campo et al., 2014 |

| OsPLDbeta1 | R/T | Blast R | Os10g0524400 | LOC_Os10g38060.1 | Kd | R to Pyricularia grisea and Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. | Yamaguchi et al., 2009 |

| OsWRKY45 | R/T | Blast R | Os05g0322900 | LOC_Os05g25770.1 | Kd OX | R to Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae, pv. oryzicola, and Magnaporthe grisea. | Tao et al., 2011 |

| OsAOS2 | R/T | Blast R | Os03g0225900 | LOC_Os03g12500.1 | OX | R to Magnaporthe grisea. | Mei et al., 2006 |

| OsWRKY76 | R/T | Blast R | Os09g0417600 | LOC_Os09g25060.1 | OX | R to Magnaporthe oryzae; cold T. | Yokotani et al., 2013 |

| OsMAPK5 | R/T | Blast R | Os03g0285800 | LOC_Os03g17700.1 | Kd OX | R to Magnaporthe grisea and Burkholderia glumae; cold, drought, and salinity T. | Xiong and Yang, 2003 |

| OsbHLH65 | R/T | Blast R | Os04g0493100 | LOC_Os04g41570.1 | Others | Defense R against rice blast. | Shin et al., 2014 |

| OsWRKY45 | R/T | Bacterial blight R | Os05g0322900 | LOC_Os05g25770.1 | Kd OX | R to Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae, pv. oryzicola, and Magnaporthe grisea. | Tao et al., 2011 |

| OsWRKY76 | R/T | Bacterial blight R | Os09g0417600 | LOC_Os09g25060.1 | OX | R to Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. | Yokotani et al., 2013 |

| OsMAPK5 | R/T | Bacterial blight R | Os03g0285800 | LOC_Os03g17700.1 | Kd OX | R to Magnaporthe grisea and Burkholderia glumae; cold, drought, and salinity T. | Xiong and Yang, 2003 |

| OsNAC4 | R/T | Bacterial blight R | Os01g0816100 | LOC_Os01g60020.1 | Kd | Bacterial blight R; HR cell death. | Kaneda et al., 2009 |

| OsWRKY71 | R/T | Bacterial blight R | Os02g0181300 | LOC_Os02g08440.1 | OX | R to Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. | Liu et al., 2007 |

| OsHI-LOX | R/T | Insect R | Os08g0508800 | LOC_Os08g39840.1 | Kd | R to rice striped stem borer and rice brown planthopper. | Zhou et al., 2009 |

| OsWRKY45 | R/T | Sheath blight R | Os05g0322900 | LOC_Os05g25770.1 | Kd OX | R to Xanthomonas oryzae, Magnaporthe grisea and Rhizoctonia solani. | Tao et al., 2011 |

| OsMAPK5 | R/T | Other disease R | Os03g0285800 | LOC_Os03g17700.1 | Kd OX | R to Magnaporthe grisea and Burkholderia glumae; cold, drought, and salinity T. | Xiong and Yang, 2003 |

| OsSRO1c | R/T | Other stress R | Os03g0230300 | LOC_Os03g12820.1 | Mutant | Apoplastic and chloroplastic oxidative stress T; temperature stress T. | You et al., 2013 |

| OsCAF1B | R/T | Other stress R | Os04g0684900 | LOC_Os04g58810.1 | Others | Wounding; ABA T. | Chou et al., 2014 |

| OsSPX1 | R/T | Other stress R | Os06g0603600 | LOC_Os06g40120.1 | Kd | Cold and oxidative stress T. | Wang C. et al., 2013 |

| ZFP179 | R/T | Other soil stress T | Os01g0839100 | LOC_Os01g62190.1 | OX | Salinity and oxidative stress T. | Sun et al., 2010 |

| OsSPX1 | R/T | Other soil stress T | Os06g0603600 | LOC_Os06g40120.1 | OX | Phosphate homeostasis. | Wang C. et al., 2013 |

| OsEATB | MT | Dwarf | Os09g0457900 | LOC_Os09g28440.1 | OX | Internode elongation; panicle branching; tillering; salinity T. | Qi et al., 2011 |

| OsPHI-1 | MT | Dwarf | Os02g0757100 | LOC_Os02g52040.1 | Kd | Dwarfism. | Aya et al., 2014 |

| OsMPS | MT | Dwarf | Os02g0618400 | LOC_Os02g40530.1 | Kd OX | Grain size; total biomass. | Schmidt et al., 2013 |

| RERJ1 | MT | Dwarf | Os04g0301500 | LOC_Os04g23550.1 | Kd OX | Dwarfism; JA sensitivity during seedling stage. | Kiribuchi et al., 2004 |

| GA2ox3 | MT | Dwarf | Os01g0757200 | LOC_Os01g55240.1 | Others | Dwarfism; gibberellin catabolism. | Lo et al., 2008 |

| TIFY11b | MT | Dwarf | Os03g0181100 | LOC_Os03g08330.1 | OX | Grain size; plant height. | Hakata et al., 2012 |

| OsDOG | MT | Dwarf | Os08g0504700 | LOC_Os08g39450.1 | OX | Dwarfism; cell elongation; regulation of gibberellin biosynthesis. | Liu et al., 2011 |

| OsBZR1 | MT | Dwarf | Os07g0580500 | LOC_Os07g39220.1 | Kd | Dwarfism; leaf angle; brassinosteroid sensitivity. | Bai et al., 2007 |

| gid1 | MT | Dwarf | Os05g0407500 | LOC_Os05g33730.1 | Mutant | Dwarfism; gibberellin sensitivity. | Ueguchi-Tanaka et al., 2005 |

| cZOGT1 | MT | Dwarf | Os04g0556500 | LOC_Os04g46980.1 | OX | Dwarfism; leaf senescence; crown root. | Kudo et al., 2012 |

| brd1 | MT | Dwarf | Os03g0602300 | LOC_Os03g40540.1 | Mutant | Dwarfism; brassinosteroid biosynthesis. | Mori et al., 2002 |

| OsCPK4 | MT | Dwarf | Os02g0126400 | LOC_Os02g03410.1 | Kd | Dwarfism. | Campo et al., 2014 |

| OsAP2-39 | MT | Dwarf | Os04g0610400 | LOC_Os04g52090.1 | OX | Dwarfism; fertility; drought T. | Yaish et al., 2010 |

| RERJ1 | MT | Shoot seedling | Os04g0301500 | LOC_Os04g23550.1 | Kd OX | Dwarfism; JA sensitivity during seedling stage. | Kiribuchi et al., 2004 |

| CYP85A1 | MT | Shoot seedling | Os03g0602300 | LOC_Os03g40540.1 | Others | Rice lamina bending and leaf unrolling by promoting castasterone (CS). | Asahina et al., 2014 |

| kch1 | MT | Shoot seedling | Os12g0547500 | LOC_Os12g36100.1 | Mutant | Coleoptile elongation. | Frey et al., 2010 |

| OsWRKY42 | MT | Culm leaf | Os02g0462800 | LOC_Os02g26430.1 | OX | Promotion of leaf senescence through ROS accumulation; plant death. | Han et al., 2014 |

| OsEATB | MT | Culm leaf | Os09g0457900 | LOC_Os09g28440.1 | OX | Internode elongation; panicle branching; tillering; salinity T. | Qi et al., 2011 |

| OsPHI-1 | MT | Culm leaf | Os02g0757100 | LOC_Os02g52040.1 | Kd | Cell size and number in culm (increased number of smaller parenchyma cells) | Aya et al., 2014 |

| OsBZR1 | MT | Culm leaf | Os07g0580500 | LOC_Os07g39220.1 | Kd | Dwarfism; leaf angle; brassinosteroid sensitivity. | Bai et al., 2007 |

| OsIAA23 | MT | Root | Os06g0597000 | LOC_Os06g39590.1 | Mutant | Root development; quiescent center identity; auxin sensitivity. | Ni et al., 2011 |

| MAIF1 | MT | Root | Os02g0671100 | LOC_Os02g44990.1 | OX | Seed germination; ABA sensitivity; root growth. | Yan et al., 2011 |

| EL5 | MT | Root | Os02g0559800 | LOC_Os02g35329.1 | Others | Maintenance of cell viability of root primordia. | Koiwai et al., 2007 |

| cZOGT1 | MT | Root | Os04g0556500 | LOC_Os04g46980.1 | OX | Dwarfism; leaf senescence; crown root. | Kudo et al., 2012 |

| OsCPK4 | MT | Root | Os02g0126400 | LOC_Os02g03410.1 | OX | Regulation of Na+ accumulation. | Campo et al., 2014 |

| Rdd1 | MT | Seed | Os01g0264000 | LOC_Os01g15900.1 | Kd OX | Grain length and width; 1000-grain weight; flowering time. | Iwamoto et al., 2009 |

| OsMPS | MT | Seed | Os02g0618400 | LOC_Os02g40530.1 | Kd OX | Grain size; total biomass. | Schmidt et al., 2013 |

| TIFY11b | MT | Seed | Os03g0181100 | LOC_Os03g08330.1 | OX | Grain size; plant height. | Hakata et al., 2012 |

| OsEATB | MT | Panicle flower | Os09g0457900 | LOC_Os09g28440.1 | OX | Internode elongation; panicle branching; tillering; salinity T. | Qi et al., 2011 |

| MSF1 | MT | Panicle flower | Os05g0497200 | LOC_Os05g41760.1 | Mutant | Spikelet determinacy; floral organ development. | Ren et al., 2016 |

| OsAP2-39 | PT | Sterility | Os04g0610400 | LOC_Os04g52090.1 | OX | Dwarfism; fertility; drought T. | Yaish et al., 2010 |

| OsCHR4 | PT | Source activity | Os07g0497000 | LOC_Os07g31450.1 | Mutant | Chloroplast development in adaxial mesophyll. | Zhao et al., 2012 |

| BE1 | PT | Source activity | Os06g0726400 | LOC_Os06g51084.1 | Others | Starch granule-binding, amylopectin structure. | Abe et al., 2014 |

| MAIF1 | PT | Germination dormancy | Os02g0671100 | LOC_Os02g44990.1 | OX | Seed germination; ABA sensitivity; root growth. | Yan et al., 2011 |

| PLDβ1 | PT | Germination dormancy | Os10g0524400 | LOC_Os10g38060.1 | Kd | Sensitivity to ABA during germination stage. | Li and Xue, 2007 |

| Rdd1 | PT | Flowering | Os01g0264000 | LOC_Os01g15900.1 | Kd OX | Grain length and width; 1000-grain weight; flowering time. | Iwamoto et al., 2009 |

| etr2 | PT | Flowering | Os04g0169100 | LOC_Os04g08740.1 | Mutant | Flowering time; ethylene sensitivity; stem starch content. | Wuriyanghan et al., 2009 |

| SPK1(SYG1) | PT | Others | Os06g0603600 | LOC_Os06g40120.1 | Kd OX | Pi-dependent inhibitor of Phosphate starvation response regulator 2 (PHR2). | Wang et al., 2014 |

| AFT | Others | Others | Os01g0185300 | LOC_Os01g09010.1 | Kd | Ester-linked ferulate content in cell walls. | Piston et al., 2009 |

| etr2 | Others | Others | Os04g0169100 | LOC_Os04g08740.1 | Mutant | Flowering time; ethylene sensitivity; stem starch content. | Wuriyanghan et al., 2009 |

| OsExo1 | Others | Others | Os01g0777300 | LOC_Os01g56940.1 | OX | Processing of double-strand break sites. | Kwon et al., 2012 |

R, resistant; T, tolerant; MT, morphological trait; OX, overexpression; Kd, knockdown.

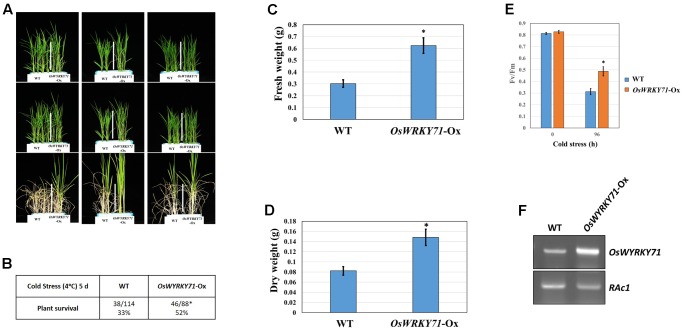

Evaluation of Cold Tolerance in a Line Over-Expressing OsWYRKY71

Plants from an Ox line for OsWYRKY71 (OsWYRKY71-Ox) under the control of CaMV35S promoter (Kim et al., 2016) and from the WT (Japonica cv. Dongjin) were grown for 10 days in plastic boxes containing soil. To test their tolerance, we then exposed them to cold stress (4oC) for 5 days and then returned them to normal growing conditions for 6 days of recovery. Survival rates were determined at the end of this experimental period. Cold stress analysis of OsWYRKY71-Ox lines was done with three replicates.

Results and Discussion

Physiological Responses of Cold-Stressed Rice Seedlings

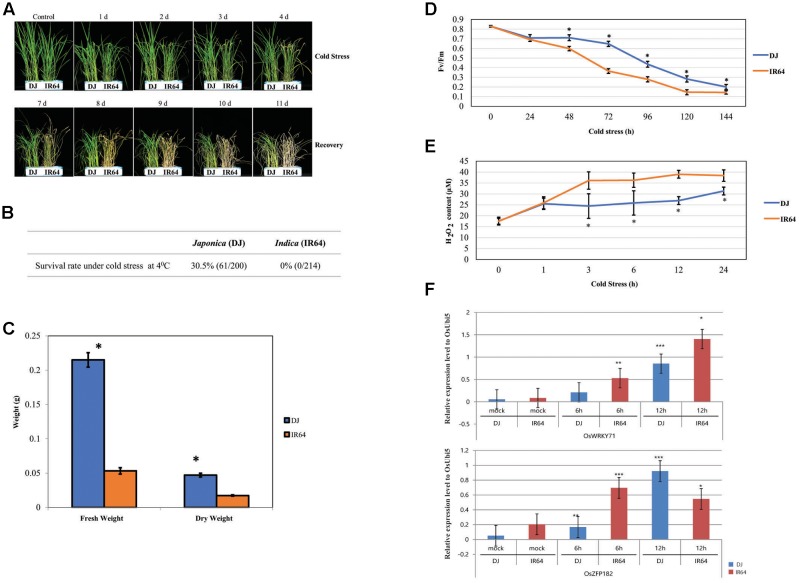

Cold stress adversely affects plant growth and yield, and rice isparticularly susceptible at the seedling stage (Zhang et al., 2014). Ouranalysis involved 10-day-old ‘DJ’ (japonica) and ‘IR64’(indica) plants exposed to 4°C for 4 days.Afterward, they recovered for 5 days at 28°C. Their phenotypes are shown in Figure 1A. At the end of this experimental period, the survival rate was 30.5% for ‘DJ’ versus 0.0% for ‘IR64,’indicating that the former was more old-tolerant (Figure 1B). The FW value was 162 mg higher for ‘DJ’ while its DW was 29 mg higher than for ‘IR64’ (Figure 1C). Prolonged cold stress also negatively affected photosynthetic efficiency, with both cultivars showing significant reductions after 24 h (Figure 1D). The decline in efficiency after 48 h was more severe for ‘IR64’ than for ‘DJ.’

FIGURE 1.

Analysis of cold stress responses by japonica and indica rice cultivars. (A) Phenotypes associated with cold-stress response by ‘DJ’ and ‘IR64’ rice seedlings observed during treatment for 4 days followed by 5 days of recovery. (B) Tolerance of seedlings based on survival rates. (C) Fresh and dry weights after recovery from cold stress. (D) Photosynthetic efficiency (Fv/Fm) after cold treatment for 4 days. (E) Determination of ROS concentrations (i.e., levels of H2O2) in seedlings after cold treatment for 24 h. (F) Expression of 2 marker genes (OsZFP182 and OsWRKY71) in stressed seedlings, using OsUbi5 as an internal control. ∗∗∗, p-value < 0.001, ∗∗, 0.001< p-value < 0.01; ∗, 0.01 < p-value < 0.05.

The accumulation of ROS, including H2O2, is a major indicator of the plant response to various abiotic stresses. We found that ‘IR64’ had higher H2O2 concentrations than did ‘DJ’ after 3 and 24 h of cold treatment (Figure 1E).

We also evaluated the expression patterns of two well-known cold stress-responsible genes, OsZFP182 and OsWRKY71 (Huang et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2016) and found that, as expected, their expression was significantly induced, and to nearly the same extent, in both cultivars (Figure 1F). This demonstrated that the tool of global transcriptome data can be broadly applied for determining and, ultimately, improving cold tolerance in rice.

Genome-Wide Identification of Cold Stress-Inducible Genes in Both japonica and indica Cultivars Using Meta-Expression Data Analysis

As a quantitative trait, tolerance to cold stress is governed by different sets of genes, and through diverse mechanisms. We used meta-expression analysis with transcriptome data and downloaded information about global candidate genes from the NCBI GEO for series GSE37940 and GSE38023 (Zhang F. et al., 2012; Zhang H. et al., 2012). After normalizing these data, we generated 63 comparisons for cold-stress treatment, as well as 49 comparisons for drought stress, 6 for high temperatures, and 4 for submergence (Supplementary Table S2). Our KMC analysis with the resultant fold-change data revealed 502 genes that were significant up-regulated upon cold stress but not under recovery conditions (Figure 2). From this, we prepared 27 comparisons with two japonica cultivars – ‘C418’ (a japonica restorer line for hybrid rice production and cold sensitive) and ‘Li-Jiang-Xin-Tuan-Hei-Gu’ (‘LTH,’ cold tolerant genotype) – and 36 comparisons with five indica cultivars – ‘IR24’ (photoperiod-insensitive, high yielding and cold sensitive variety), ‘IR64’ [variety with moderate tolerance toward toxicity in response to various molecules including salt, alkali, iron, and boron as well as deficiencies in phosphorus and zinc, but sensitivity to cold stress], ‘K354’ (a BC2F6 introgression line as a progeny of C418 and cold tolerant variety), ‘Huahui 1’ (’HH1,’ insect-resistant variety as a progeny of Minghui 63), and ‘Minghui 63’ (‘MH,’ heat tolerant variety and a parental line of HH1). Their upregulation was conserved between japonica and indica cultivars. All of these genes provide potential for a broader range of applications to enhance cold tolerance in rice. These 502 DEGs were used for further analysis of the cold-stress response (Supplementary Table S3).

FIGURE 2.

Heatmap of genes up-regulated under stress in both japonica and indica cultivars. Panel above heatmap indicates type of abiotic stress applied; parentheses indicate number of stress/control in each treatment. Panel below heatmap shows detailed information for “main target” samples under cold stress. Gray box, indica cultivars; black, japonica cultivars; blue, cold stress/control; and brown, recovery/control. Indica cultivars: ‘IR64,’ ‘Huahui 1’ (‘HH1’), ‘Minghui 63’ (‘MH’), ‘K354,’ and ‘IR24’; japonica cultivars: ‘C418’ and ‘Li-Jiang-Xin-Tuan-Hei-Gu’ (‘LTH’).

Validation of Cold-Inducible Genes in Rice Roots Using the GUS Reporter System and qRT-PCR

Promoter traps employing the GUS reporter gene system have been used to identify promoters involved in regulating tissue-specific and stress-responsive expression patterns (Jung et al., 2005, 2006). Our meta-expression analysis identified the top 50 genes showing >3.5-fold upregulation by cold stress when compared with the control (Supplementary Table S3). We then searched and identified 52 potential promoter trap lines of 43 candidate genes and examined GUS expression patterns in 7-day-old seedlings. The lines for two genes (PFG 3A-50649 for LOC_Os01g31370 and PFG 1C-08613 for LOC_Os03g49830) displayed GUS expression in the roots after plants were exposed to stress for 24 h (Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure S1). This cold-related expression was also verified by qRT-PCR (Supplementary Figure S1). Previous studies using a promoter-GUS vector or promoter trap system have confirmed the upregulation of LOC_Os10g41200 in response to cold stress (Su et al., 2010; Jeong and Jung, 2015). Our findings demonstrated that the promoter trap system, when combined with qualified genome-wide transcriptome data, is a very effective way for quickly identifying the activity of an endogenous promoter. This enables researchers to develop novel promoters for future applications.

FIGURE 3.

Validation of expression patterns for two cold stress-responsive genes using GUS reporter systems. Promoter trap lines using GUS reporter gene were selected and tested for GUS activity. Promoter trap line for LOC_Os01g31370, Line PFG 3A-50649 (right), and that of LOC_Os03g49830, Line PFG 1C-08613 (left) were confirmed through co-segregation test of GUS expression and T-DNA insertion through genotyping analysis. Upper panel, GUS-staining data from promoter trap lines under normal growing conditions; lower panel, lines under cold-stress conditions. Homozygous progeny of T-DNA insertion for each of two lines were used.

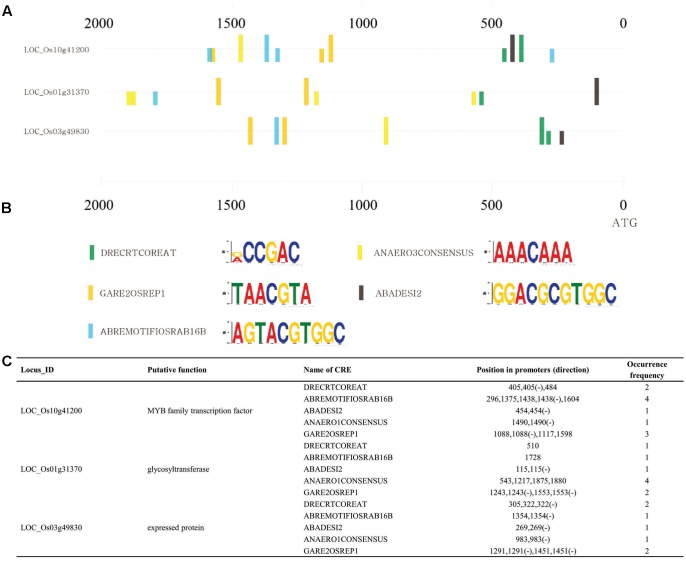

Analysis of Cis-Regulatory Elements Conserved in Promoters of Three Cold-Inducible Genes Confirmed by the GUS Reporter System

To identify the cis-regulatory regulatory elements (CREs) associated with the response to cold, we used promoter regions in 2-kb sequences upstream of ATG of the two cold-inducible genes (LOC_Os01g31370 and LOC_Os03g49830) that had been validated through GUS trap assays and also included the promoter region of LOC_Os10g41200, which have previously been reported as a cold-inducible gene using GUS reporter systems (Su et al., 2010; Rerksiri et al., 2013; Jeong and Jung, 2015). Through in silico analysis of CREs, we revealed the presence of common 51 CREs in the promoter regions from the PLANTPAN 2.0 database9 (Chow et al., 2016) and MEME tool10 (Bailey et al., 2006). Selected promoter regions and CREs are summarized in Supplementary Table S4. Of these, we have more interest in five unique CREs: DRECRTCOREAT (RCCGAC), ABREMOTIFIOSRAB16B (AGTACGTGGC), ABADESI2 (GGACGCGTGGC), GARE2OSREP1 (TAACGTA), and ANAERO3CONSENSUS (TCATCAC) (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table S4). DRECRTCOREAT is a core motif of dehydration-responsive element/C-repeat (DRE/CRT) found in the promoters of genes from various species. Previous studies reported that OsDREB1A, AtDREB1A and ZmDREB1A bound to (G/ACCGAC) with the different efficiency by competitive DNA binding assays (Sakuma et al., 2002; Dubouzet et al., 2003; Qin et al., 2004) and OsDREB gene encodes transcription activators that function in drought, salt and cold-responsive gene expression (Dubouzet et al., 2003). However, although the Aloe DREB1 can bind to the DRE, it may also bind to other CREs effectively, which can function in a new cold-induced signal transduction pathway (Wang and He, 2007). It has been known that phytohormones including ABA, auxin, gibberellic acid (GA), salicylic acid (SA) and ethylene are related to the cold responses positively or negatively (Miura and Furumoto, 2013; Verma et al., 2016). Among the ABA-responsive CREs, we found that ABREMOTIFIOSRAB16B and ABADESI2 earlier identified from rice Osrab16B promoter and wheat histone H3 promoter were related to ABA-regulated transcription (Terada et al., 1993; Ono et al., 1996; Busk and Pagès, 1998). In addition, GARE1OSREP1 is involved in Gibberellin-responsive element (GARE) found in rice OsREP-1 promoter (Ogawa et al., 2003; Sutoh and Yamauchi, 2003). ANAERO3CONSENSUS found in promoters of anaerobic genes is involved in the fermentative pathway and related to anaerobic response (Mohanty et al., 2005). In summary, DRECRTCOREAT might be related to cold-preferred expression, and ABREMOTIFIOSRAB16B, ABADESI2 and GARE1OSREP1 might be associated with crosstalk between phytohormones and cold stress-preferred expression. The other CREs not mentioned here might have novel roles in driving cold stress-preferred expression and further experiments will be required to clarify our estimation.

FIGURE 4.

Identification of CREs conserved in three cold-inducible genes. Consensus CREs in promoters of cold-inducible genes were studied with GUS reporter systems, using 2-kb upstream sequences of ATG for LOC_Os01g31370, LOC_Os03g49830, and LOC_Os10g41200 to confirm cold induction in planta. (A) Distribution of five CREs conserved in promoters of three cold-inducible genes but not in those of randomly selected genes. (B) Names and conserved sequences presented using MEME suit. (C) Positions and frequency were determined for five CREs in promoters of above three genes.

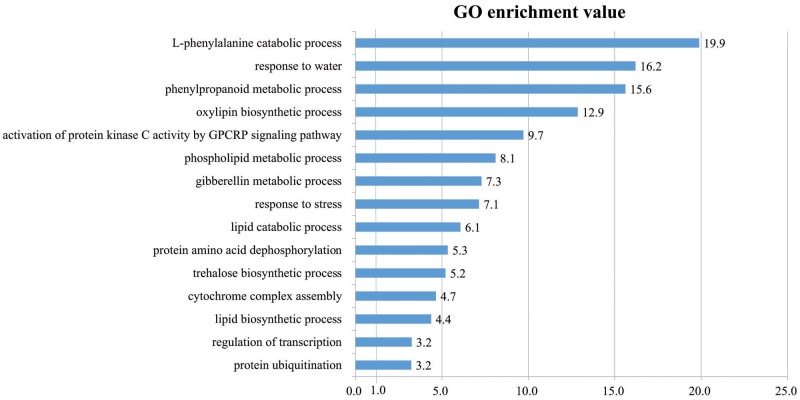

Analysis of GO Enrichment Reveals Biological Processes Associated with Cold Stress Responses in Rice Roots

To determine the functions of 502 DEGs up-regulated by cold stress in rice roots, we studied their GO terms within the ‘biological process’ category. In all, 15 terms were highly over-represented in our gene list, with p-values < 0.05 and fold-enrichment values of >2-fold (Figure 5 and Supplementary Table S5). We have also previously reported this (Jung et al., 2008b). The terms included ‘L-phenylalanine catabolic process’ (19.9-fold enrichment), ‘response to water’ (16.2), ‘phenylpropanoid metabolic process’ (15.6), ‘oxylipin biosynthetic process’ (12.9), ‘activation of protein kinase C activity by GPCRP signaling pathway’ (9.7), ‘phospholipid metabolic process’ (8.1), ‘gibberellin metabolic process’ (7.3), ‘response to stress’ (7.1), ‘lipid catabolic process ’ (6.1), ‘protein amino acid dephosphorylation’ (5.3), ‘trehalose biosynthetic process’ (5.2), ‘cytochrome complex assembly’ (4.7), ‘lipid biosynthetic process’ (4.4), ‘regulation of transcription’ (3.2), and ‘protein ubiquitination’ (3.2).

FIGURE 5.

Gene Ontology enrichment analysis in ‘Biological Process’ category for genes up-regulated in response to cold stress. In all, 15 GO terms were over-represented by >2-fold enrichment value, with p-values < 0.05. Details of GO assignment are presented in Supplementary Table S4.

Of these, ‘L-phenylalanine catabolic process’ was the most significantly enriched by cold stress while another critical component in that response was ‘phenylpropanoid metabolic process.’ Transcriptome profile analysis of maize (Zea mays) seedlings in response to cold stress has shown that 31 DEGs for phenylalanine metabolism are induced (Shan et al., 2013). Transcript and metabolic profiling of Arabidopsis thaliana (Charlton et al., 2008) has indicated that phenylpropanoids, along with Lys, Met, Trp, Tyr, Arg, Cys, and the polyamine biosynthetic pathway, are important metabolites that are highly accumulated in response to cold stress. Profiling of maize seedling transcripts by Shan et al. (2013) has also revealed the induction of 54 DEGs for phenylpropanoid metabolism. All of these results suggest that the phenylpropanoid metabolic pathway is activated when various plant species are exposed to cold stress.

Metabolic profiling of Camellia sinensis in response to cold (Wang X.C. et al., 2013) has shown that expression is increased for genes involved in the signal transduction mechanism. Three oxylipin biosynthetic-related genes and two trehalose biosynthetic genes are highly expressed in cold-tolerant Elymus nutans (Fu et al., 2016). Moreover, transcriptomics profiling of Lotus japonicus under cold stress has demonstrated that those conditions lead to the upregulation of the phospholipid metabolic process (Calzadilla et al., 2016).

Transcriptome profiling has presented the upregulation of GA metabolism in cold-stressed ‘Meyer’ zoysiagrass (Wei et al., 2015) and greater than threefold induction of gibberellin 2-beta-dioxygenase genes in cassava, which is also related to responses to abiotic and biotic stimuli (An et al., 2012). All of these reports indicate that the gibberellin metabolic pathway is activated during periods of cold stress.

Genes for ‘lipid catabolic process,’ ‘protein amino acid dephosphorylation,’ ‘cytochrome complex assembly,’ ‘regulation of transcription,’ and ‘protein ubiquitination’ also have important roles in the abiotic-stress response (see, e.g., data in Figure 5). For example, in A. thaliana, several lipid catabolism enzymes in rice (in particular, phospholipids A and D) are activated by low temperatures, as manifested by the heightened accumulation of fatty acids (Wang et al., 2006; Usadel et al., 2008). Serine phosphorylation or dephosphorylation is involved in cold activation signaling of Arabidopsis ICE1, and its Ox in Isatis tinctoria confers cold tolerance (Chinnusamy et al., 2003; Xiang et al., 2013). Campos et al. (2003) have reported that a cold-tolerant genotype of Coffea sp. copes with chilling through an enhanced lipid biosynthetic process. Regulation of transcription is also important for cold tolerance. For example, in Arabidopsis, ICE1 and an R2R3-type MYB control the transcriptional regulation of DREB TFs within the mechanism for cold tolerance (Agarwal et al., 2006; Miura et al., 2007). We also identified ‘Protein ubiquitination’ as another important GO term that is also linked with cold tolerance. For example, Arabidopsis HOS1 mediates the ubiquitination and degradation of ICE1 and negatively regulates the response to cold stress (Dong et al., 2006). In summary, the biological processes that we identified here as being closely associated with the cold-stress response provide novel and informative resources for improving our knowledge about regulatory factors involved in the molecular mechanism(s) that enable plants to cope in a low-temperature environment.

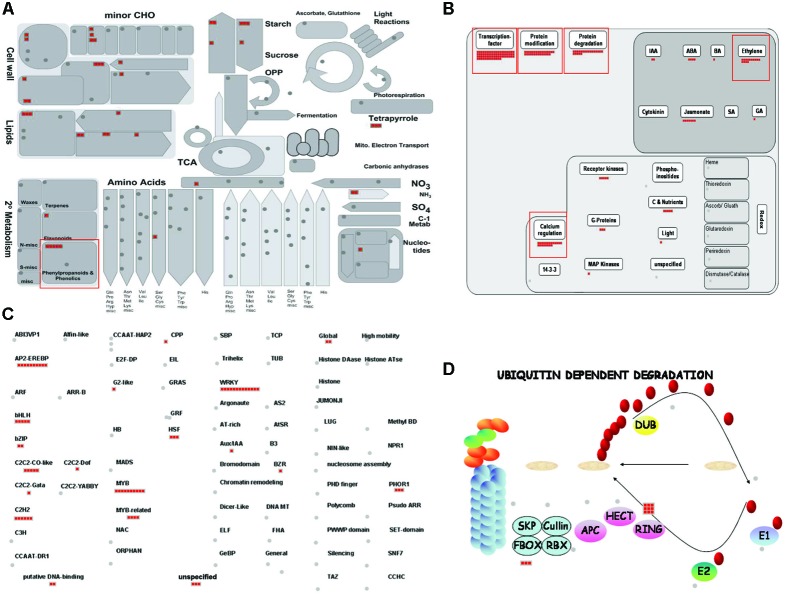

MapMan Analysis of Cold-Related Genes in Rice Roots

The MapMan program is very effective for visualizing diverse overviews associated with high-throughput transcriptome data (Jung and An, 2012). We uploaded Locus IDs for 502 DEGs for the cold-stress response (Supplementary Table S3) to various overviews installed in that program. Among them, 79 elements were assigned to the ‘RNA’ category, 58 to ‘protein,’ 36 to ‘signaling,’ 25 to ‘miscellaneous function’ (‘misc’), 22 to ‘hormone metabolism,’ 17 to ‘stress,’ 14 to ‘development,’ 13 to ‘transport,’ 10 each to ‘lipid metabolism’ and ‘cell wall,’ 7 to ‘secondary metabolism,’ and a smaller number to other functional groups (Supplementary Table S6). Another 154 genes did not have assigned MapMan terms. In particular, the identification of 17 cold stress-regulated elements supports our proposal that they have potential significance for enhancing tolerance when our candidate genes are expressed.

Analysis of Metabolism Overview Associated with the Cold-Stress Response in Rice

To investigate the significant metabolic pathways involved in the response to cold stress, we analyzed the Metabolism overview associated with 502 DEGs (Figure 6). Among the 44 elements found there, secondary metabolism included six for phenylpropanoids; nine for lipid metabolism, e.g., phospholipid biosynthesis and lipid degradation; 10 for cell wall metabolism, including cellulose synthase and modification; three for mitochondrial electron transport; seven for major carbohydrate (CHO) metabolism; four for minor CHO metabolism; as well as several others related to this stress, such as amino acid, nitrogen, and nucleotide metabolisms (Figure 6A and Supplementary Table S6). These results implied that a rice plant triggers those metabolic pathways as part of its stress response. Similar to our findings from the GO enrichment analysis, ‘L-phenylalanine catabolic process,’ ‘L-phenylalanine metabolic process,’ and category ‘secondary metabolism’ (including ‘phenylpropanoid metabolism’) were over-represented.

FIGURE 6.

MapMan analysis of rice genes associated with response to cold stress. Overviews of Metabolism (A), Regulation (B), Transcription (C), and Ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation pathway (D) were mapped with selected cold-inducible genes. Red boxes, groups of genes up-regulated by cold stress. Details are presented in Supplementary Table S6.

Analyses of Regulation, Transcription, and Ubiquitin-Dependent Proteasome Pathway Overviews Associated with the Cold-Stress Response in Rice

Our Regulation overview of 502 DEGs demonstrated that 73 TFs, 30 genes related to protein modification, 21 associated with protein degradation, and 22 related to hormone metabolism were up-regulated in rice during periods of cold stress (Figure 6B). Of these, the TFs were the most abundant, meaning that they are largely involved in regulating the response and tolerance of rice to such conditions. Therefore, those genes should be considered candidates for further study to regulate the cold-stress response in rice. Accordingly, we found 13 WRKY TFs, 10 MYB and four MYB-related TFs, 10 Apetala2/Ethylene Responsive Element Binding Proteins (AP2/EREBPs), five Basic Helix-Loop-Helix (bHLH) genes, five Constans (CO)-like zinc finger family TFs, five C2H2 zinc finger family TFs, and other TFs for this response (Figure 6C and Supplementary Table S6).

In plants, the WRKY TFs have been more actively studied than others, and most of them have positive roles in the cold-stress response in various plant species, including Ipomoea batatas, where the function of a WRKY TF was first described (Ishiguro and Nakamura, 1994). This TF contains a WYRKY domain and a zinc-finger motif. Marè et al. (2004) have reported the role of Hv-WRKY38 in the cold-stress response by Hordeum vulgare, and Ox of WYRKY76 and WYRKY71 has been shown to increase cold tolerance in rice (Yokotani et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2016). Likewise, Ox of CsWYRKY46 in Cucumis sativus regulates tolerance to chilling and freezing (Zhang et al., 2016), and the cold-inducible BcWYRKY46 from Brassica campestris enhances cold tolerance in transgenic tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) (Wang et al., 2012). In contrast, OsWYRKY45 and OsWRKY13 negatively regulate cold tolerance in rice (Qiu et al., 2008; Tao et al., 2011), while WYRKY34 mediates the cold sensitivity of mature pollen in A. thaliana (Zou et al., 2010) CsWRKY2, a novel WRKY gene from Camellia sinensis, is involved in cold stress responses (Wang Y. et al., 2016).

Like WRKY TFs, MYB TFs have important roles in cold tolerance. They include OsMYB4 OsMYB2 and MYBS3 in rice (Vannini et al., 2004; Su et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2012), MYB15 and HOS10 in Arabidopsis (Zhu et al., 2005; Agarwal et al., 2006), and GmMYBj1 in soybean (Su et al., 2014); and TaMYB3R1 in Triticum aestivum (Cai et al., 2015). Whereas all of those TFs have positive effects, MYBC1 in Arabidopsis negatively regulates cold tolerance (Zhai et al., 2010).

The AP2/EREBP TFs also enhance cold tolerance. They include JcDREB, JcCBF2, BnaERF-B3-hy15, DEAR1, ZmDREB1A, OsDREB1D, and ZmDBP4 analyzed in Arabidopsis (Qin et al., 2004; Tsutsui et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2010, 2014; Tang et al., 2011; Xiong et al., 2013); and JERF1, OsDREB1, and AtDREB1A in tobacco (Kasuga et al., 2004; Li et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2007).

A major TF family of other TFs involved in cold tolerance is bHLH. ICE1, ICE2, VabHLH1, and OrbHLH001 analyzed in Arabidopsis (Chinnusamy et al., 2003; Fursova et al., 2009; Li et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2014) and OsbHLH1 in rice (Wang et al., 2003) are involved in cold tolerance. Next, HOS1, a member of the CO-like zinc finger family, regulates cold tolerance in Arabidopsis via CONSTANS degradation (Jung et al., 2012), while OsZFP245, a member of the C2H2 zinc finger family, confers such tolerance in rice (Huang et al., 2009).

Related to protein degradation, signal transduction, and hormone metabolism, a few studies have been conducted. Therefore, future analyses of uncharacterized TFs and the regulatory elements associated with protein degradation, signal transduction, and hormone metabolism identified in this study might shed the light on the effective methods for improving cold tolerance in rice.

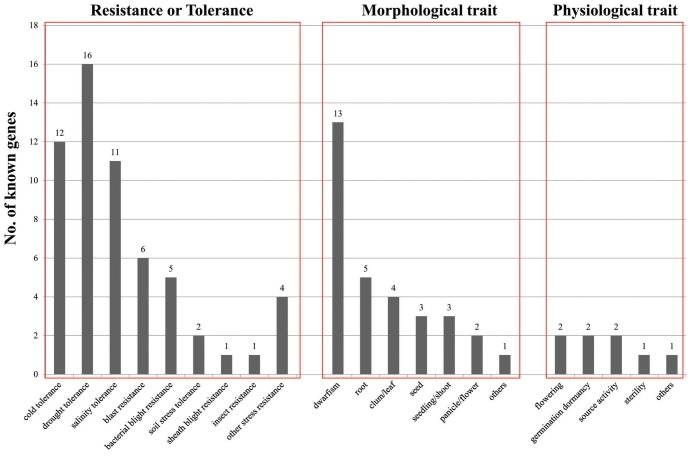

Evaluation of Candidate Genes Associated with Cold Stress Using Rice Genes with Known Functions

To evaluate the significance of our candidate genes, we searched the literature to determine if functions for them have been reported previously. This was accomplished with the online OGRO database, which provides a thorough summary of rice genes that have been characterized through molecular and genetic techniques (Yamamoto et al., 2012). That summary presents the roles of 49 genes according to three agronomic trait categories: morphological, physiological, and resistance/tolerance. The functional identification of genes related to resistance/tolerance traits is the most abundant, with 27 genes being part of that category, including 12 genes involved in cold tolerance; 16, drought tolerance; 11, salinity tolerance; six, blast resistance; five, bacterial blight resistance; two, soil stress tolerance; one each for sheath blight resistance and insect resistance; and four for other stress resistances (Figure 7). Of these, 17 genes are partially responsible for at least two traits in that resistance/tolerance category. OsMAPK5 and OsWRKY45 are involved in tolerance to both biotic stress (bacterial blight and blast) and abiotic stress (drought, salinity, and cold). Others include OsMYB2, ZFP182, OsDREB1A, OsDREB1B, and OsDREB1C, for responses to drought, salinity, and cold; OsbZIP52/RISBZ5 and OsCAF1B, cold and drought; OsTPP1, cold and salinity; and OsCPK4, OsCDPK7, and OsNAC045, drought and salinity. The results from our transcriptome analysis had also suggested that these last three are active in the cold-stress response. We found it interesting that genes induced by low temperatures also function in other abiotic-stress responses. This implies that regulation of those responses is very complex and that intensive crosstalk might occur among them.

FIGURE 7.

Distribution of functionally characterized genes according to three major agronomic categories. Y-axis, number of known genes; X-axis, minor functional categories in three major functional categories, presented in order of “Resistance or Tolerance,” “Morphological trait,” and “Physiological trait”.

Regarding morphological traits, 13 genes are related to dwarfism, five to rooting, four to culms/leaves, three to seeds, three to shoots/seedlings, two to panicles/flowers, and three to other plant components (Figure 7). These results indicate that the cold stress-responsive genes studied here might also affect various traits, e.g., dwarfism, that can inhibit or delay normal growth. Regarding physiological traits, we found that two genes each are related to flowering, germination dormancy, and source activity, while one is related to sterility, and one to other traits (Figure 7). Because our findings demonstrate an interaction between cold stress and diverse morphological/physiological traits, we suggest that future studies should screen mutants and focus on their morphological and physiological phenotypes while also screening phenotypes under cold-stress conditions.

Evaluating the Functional Significance of Cold-Inducible Genes Using a Gain-of-Function Mutant for OsWRKY71

Among the cold-inducible genes identified in our study,OsWRKY71 is induced by cold stress(Figure 1F). As we have reported previously(Kim et al., 2016), its Ox leads to cold tolerance(Figure 8). The survival rate is 19% higherfor OsWRKY71-Ox lines than for the WT, and the transgenics also have 30% higher FWs and 60% higher DWs. EstimatingFv/Fm values is a good way to depict photosynthetic efficiency under cold stress. Our data indicated that, after 96 h of chilling treatment, this efficiency in OsWRKY71-Ox lines decreased from 0.8 to 0.5 while that value in the WT declined from 0.8 to 0.3. Therefore, the Ox lines are 25% more efficient and OsWRKY71 confers cold tolerance.

FIGURE 8.

Cold-stress response mediated by OsWYRKY71 using Ox line. (A) Phenotype of response by OsWYRKY71-Ox line observed after 10-DAG rice seedlings were exposed to cold treatment for 5 days, followed by 6 days of recovery. (B) Cold tolerance of OsWYRKY71-Ox line, based on survival rates. (C) Fresh weights of OsWYRKY71-Ox line compared with WT after recovery. (D) Dry weights of OsWYRKY71-Ox line compared with WT after recovery. (E) Fv/Fm rates compared between OsWYRKY71-Ox line and WT during cold-stress period. (F) RT-PCR results for OsWYRKY71-Ox line and we used RAc1 as an internal control.∗, 0.01 < p-value < 0.05.

Hypothetical Model for Regulating the Cold-Stress Response that Is Conserved between japonica and indica Rice Cultivars

The response to low temperatures can be divided into four steps: perception of cold stress, signaling cascades for the response, regulation of gene expression, and protection from freezing damage. Our proposed model (Figure 9) is based on published physiological and biochemical aspects as well as reports of functions for genes involved in the relevant signaling and transcriptional pathways.

FIGURE 9.

Overview of regulatory pathway for cold-stress signaling in rice. Signaling and transcriptional regulatory pathways for cold tolerance have four steps: cold perception (blue boxes), signaling cascades (green boxes), gene expression cascades (brown boxes)/protein degradation (light-brown boxes), and protection from cold (tolerance) through activation of target genes (pink boxes). Cold-inducible candidate genes were mapped to individual boxes and are presented as locus IDs. Red-colored locus IDs are genes previously characterized for cold-stress responses, with each name indicated either on left side or below corresponding ID. Brown-colored locus IDs are genes previously characterized but not directly linked with cold-stress response.

We theorize that the first reaction by a plant to chilling is to increase membrane rigidity. This is followed by the generation of ROS, then regulation of phosphate homeostasis and activation of calcium receptors and histidine kinases. The ensuing signal transduction cascades are coupled with signal perception. Examples include MAP kinase cascades and a two-component signaling system by histidine kinase. The former is more likely because the cascades of MAP kinase (OsMAPK5/LOC_Os03g17700.1), MAP kinase kinase (MAP2K; OsMKK4/LOC_Os02g54600.1), and MAP kinase kinase kinase (MAP3K, seven members in Figure 9), are stimulated in response to cold stress, making them the most probable candidates for this pathway. Of them, it has been known that OsMAPK5 positively regulates tolerance to cold temperatures and other sources of stress (Xiong and Yang, 2003).

For the latter possibility, the processes might be more complex. In response to cold, plants use Ca2+ as a signal. Although we did not yet identify the histidine kinase genes in rice showing significant induction under cold stress, the signal received by a Ca2+ channel might bind to a Ca2+ sensor, such as calmodulin (CaM), and CaM-like protein might stimulate Ca2+/CaM-dependent protein kinases as suggested in Figure 9. Thereafter, gene expression is regulated by TFs through a process that incorporates CBF/DREB-dependent or -independent pathways.

In the case of the CBF/DREB-dependent pathway, a signal from the map kinase cascades is recognized by ICE1, which encodes a bHLH TF that activates the expression of DREB genes in the downstream pathway by directly binding the promoter regions. This results in stimulation of cold stress-responsive genes that are required for altering cellular metabolism. OsbHLH148 or RERJ1 are probable candidate genes, having the same roles as ICE1 in Arabidopsis, i.e., OsbHLH148 is involved in drought tolerance and RERJ1 functions in normal plant growth and development (Seo et al., 2011). OsDREB1A, OsDREB1B, and OsDREB1C have roles in tolerance to cold, drought, and salinity by triggering the expression of target genes (Ito et al., 2006). Regarding the CRT/DREB-independent pathway, TFs such as OsWRKY71 (Kim et al., 2016), OsWRKY76 (Yokotani et al., 2013), OsbZIP52 (Liu et al., 2012), ZFP182 (Huang et al., 2012), and OsMYB2 (Yang et al., 2012) are components of the trait for cold stress response. For example, a rice line that over-expressor of OsbZIP52 displays a cold-sensitive phenotype (Liu et al., 2012) and the application of such stress induces the expression of OsbZIP52, which then negatively affects the extent of that tolerance.

Although the functions of most genes for cold tolerance have not yet been defined, other types of TFs identified in our meta-expression and MapMan analyses might also be important for regulating tolerance, as indicated by the TF overview presented by MapMan (Figure 6 and Supplementary Table S6).

Among other processes, HOS1, encoding the ring type E3 ligase, participates in the degradation process of ICE1 that is stimulated at low temperature, resulting in inactivation of the CRT/DREB-dependent transcription regulation pathway (Chinnusamy et al., 2003; Dong et al., 2006). Likewise, OST1, encoding the well-known Ser /Thr protein kinase, is activated in response to cold and phosphorylates ICE1, leading to its stability and transcriptional activity (Ding et al., 2015). However, OST1 also hinders the interaction between HOS1 and ICE1, subsequently leading to the degradation of ICE1 under cold stress when HOS1 is suppressed. OsCAF1B, with RNase D activity, functions in post-transcriptional regulation and may affect various pathways for cold tolerance (Chou et al., 2014). OsTPP1 has a role in resistance to abiotic stress. At low temperatures, it also positively regulates the expression of tolerance genes by participating in the glucose deprivation signaling pathway (Ge et al., 2008). Despite these numerous reports, however, all of these hypotheses must still be verified through further experiments.

Cold stress is one of the main environmental factors that adversely affect plant growth and yield. Thus, it is important that we understand this stress signaling and its regulatory network if we are to develop cultivars with greater tolerance. To this end, we have produced a hypothetical model that considers our current findings as well as data derived from earlier research.

Conclusion

Our study goal was to identify low-temperature-responsive genes that can be commonly used by rice researchers throughout the world. For this, we collected a broad range of genome-wide transcriptome data produced from plants under low-temperature conditions. This information included data deposited from published microarrays or re-processed from RNA-seq analyses. The 502 genes identified here are conserved between japonica and indica cultivars, two representative subspecies of rice. Results of bioinformatics analyses using GO enrichment and MapMan tools for these candidate genes was applied to reveal important biological processes and related metabolic and regulatory pathways. In addition, we constructed a possible regulatory network based on such information. Serving as a valuable foundation for future research, our proposed model can help in the discovery of key regulatory genes that confer cold tolerance. This can be accomplished by using a gene-indexed mutant collection or biotechnological approaches that are well-established in rice.

Author Contributions

K-HJ, MK, and S-RK design overall experimental schemes. MK and Y-SG performed experiments. MK and K-HJ wrote manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Next-Generation BioGreen 21 Program PJ01192701 to S-RK and Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2016R1D1A1A09919568 to K-HJ, the Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

Abbreviations

- CREs

cis-regulatory elements

- DAG

days after germination

- DEG

differentially expressed gene

- FASTA

Fast Alignment Search Tool

- GEO

gene expression omnibus

- GO

gene ontology

- GUS

ββ-glucuronidase

- KMC

K-means clustering

- MAST

Motif Alignment and Search Tool

- Mev

Multiple Experiment Viewer

- MS

Murashige and Skoog

- NCBI

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- OGRO

overview of functionally characterized genes in rice online database

- Ox

overexpression

- PPI

protein–protein interaction

- RGAP

Rice Genome Annotation Project

- TF

transcription factor

- TOMTOM

TF-binding site motifs found by the motif comparison tool

- WT

wild type.

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2017.01120/full#supplementary-material

Validation of expression patterns for three genes (LOC_Os03g49830, LOC_Os10g41200, and LOC_Os01g31370) under cold stress using qRT-PCR analysis. ∗∗∗, p-value < 0.001.

References

- Abe N., Asai H., Yago H., Oitome N. F., Itoh R., Crofts N., et al. (2014). Relationships between starch synthase I and branching enzyme isozymes determined using double mutant rice lines. BMC Plant Biol. 14:80 10.1186/1471-2229-14-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal M., Hao Y., Kapoor A., Dong C.-H., Fujii H., Zheng X., et al. (2006). A R2R3 type MYB transcription factor is involved in the cold regulation of CBF genes and in acquired freezing tolerance. J. Biol. Chem. 281 37636–37645. 10.1074/jbc.M605895200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An D., Yang J., Zhang P. (2012). Transcriptome profiling of low temperature-treated cassava apical shoots showed dynamic responses of tropical plant to cold stress. BMC Genomics 13:64 10.1186/1471-2164-13-64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahina M., Tamaki Y., Sakamoto T., Shibata K., Nomura T., Yokota T. (2014). Blue light-promoted rice leaf bending and unrolling are due to up-regulated brassinosteroid biosynthesis genes accompanied by accumulation of castasterone. Phytochemistry 104 21–29. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aya K., Hobo T., Sato-Izawa K., Ueguchi-Tanaka M., Kitano H., Matsuoka M. (2014). A novel AP2-type transcription factor, SMALL ORGAN SIZE1, controls organ size downstream of an auxin signaling pathway. Plant Cell Physiol. 55 897–912. 10.1093/pcp/pcu023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai M. Y., Zhang L. Y., Gampala S. S., Zhu S. W., Song W. Y., Chong K., et al. (2007). Functions of OsBZR1 and 14-3-3 proteins in brassinosteroid signaling in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 13839–13844. 10.1073/pnas.0706386104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey T. L., Williams N., Misleh C., Li W. W. (2006). MEME: discovering and analyzing DNA and protein sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 34 W369–W373. 10.1093/nar/gkl198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett T., Troup D. B., Wilhite S. E., Ledoux P., Evangelista C., Kim I. F., et al. (2011). NCBI GEO: archive for functional genomics data sets–10 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 39 D1005–D1010. 10.1093/nar/gkq1184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busk P. K., Pagès M. (1998). Regulation of abscisic acid-induced transcription. Plant Mol. Biol. 37 425–435. 10.1023/A:1006058700720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X., Cai M., Lou L. (2015). Identification of differentially expressed genes and small molecule drugs for the treatment of tendinopathy using microarray analysis. Mol Med Rep. 11 3047–3054. 10.1016/j.gene.2014.12.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzadilla P. I., Maiale S. J., Ruiz O. A., Escaray F. J. (2016). Transcriptome response mediated by cold stress in Lotus japonicas. Front. Plant. Sci. 7:374 10.3389/fpls.2016.00374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo S., Baldrich P., Messeguer J., Lalanne E., Coca M., San Segundo B. (2014). Overexpression of a calcium-dependent protein kinase confers salt and drought tolerance in rice by preventing membrane lipid peroxidation. Plant Physiol. 165 688–704. 10.1104/pp.113.230268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos P. S., Quartin V., Ramalho J. C., Nunes M. A. (2003). Electrolyte leakage and lipid degradation account for cold sensitivity in leaves of Coffea sp. plants. J. Plant Physiol. 160 283–292. 10.1078/0176-1617-00833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao P., Jung K. H., Choi D., Hwang D., Zhu J., Ronald P. C. (2012). The rice oligonucleotide array database: an atlas of rice gene expression. Rice (NY) 5 17 10.1186/1939-8433-5-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang W. C., Lee T. Y., Huang H. D., Huang H. Y., Pan R. L. (2008). PlantPAN: plant promoter analysis navigator, for identifying combinatorial cis-regulatory elements with distance constraint in plant gene groups. BMC Genomics 9:561 10.1186/1471-2164-9-561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton A. J., Donarski J. A., Harrison M., Jones S. A., Godward J., Oehlschlager S., et al. (2008). Responses of the pea (Pisum sativum L.) leaf metabolome to drought stress assessed by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Metabolomics 4 312–327. 10.1007/s11306-008-0128-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chawade A., Lindlöf A., Olsson B., Olsson O. (2013). Global expression profiling of low temperature induced genes in the chilling tolerant japonica rice Jumli Marshi. PLoS ONE 8:e81729 10.1371/journal.pone.0081729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnusamy V., Ohta M., Kanrar S., Lee B. H., Hong X., Agarwal M., et al. (2003). ICE1: a regulator of cold-induced transcriptome and freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 17 1043–1054. 10.1101/gad.1077503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou W. L., Huang L. F., Fang J. C., Yeh C. H., Hong C. Y., Wu S. J., et al. (2014). Divergence of the expression and subcellular localization of CCR4-associated factor 1 (CAF1) deadenylase proteins in Oryza sativa. Plant Mol. Biol. 85 443–458. 10.1007/s11103-014-0196-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow C. N., Zheng H. Q., Wu N. Y., Chien C. H., Huang H. D., Lee T. Y., et al. (2016). PlantPAN 2.0: an update of plant promoter analysis navigator for reconstructing transcriptional regulatory networks in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 D1154–D1160. 10.1093/nar/gkv1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu V. T., Gottardo R., Raftery A. E., Bumgarner R. E., Yeung K. Y. (2008). MeV+R: using MeV as a graphical user interface for Bioconductor applications in microarray analysis. Genome Biol. 9:R118 10.1186/gb-2008-9-7-r118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y., Li H., Zhang X., Xie Q., Gong Z., Yang S. (2015). OST1 kinase modulates freezing tolerance by enhancing ICE1 stability in Arabidopsis. Dev. Cell 32 278–289. 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong C. H., Agarwal M., Zhang Y., Xie Q., Zhu J. K. (2006). The negative regulator of plant cold responses, HOS1 is a RING E3 ligase that mediates the ubiquitination and degradation of ICE1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 8281–8286. 10.1073/pnas.0602874103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubouzet J. G., Sakuma Y., Ito Y., Kasuga M., Dubouzet E. G., Miura S., et al. (2003). OsDREB genes in rice, Oryza sativa L., encode transcription activators that function in drought-, high-salt- and cold-responsive gene expression. Plant J. 33 751–763. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01661.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey N., Klotz J., Nick P. (2010). A kinesin with calponin-homology domain is involved in premitotic nuclear migration. J. Exp. Bot. 61 3423–3437. 10.1093/jxb/erq164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J., Miao Y., Shao L., Hu T., Yang P. (2016). De novo transcriptome sequencing and gene expression profiling of Elymus nutans under cold stress. BMC Genomics 17:870 10.1186/s12864-016-3222-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fursova O. V., Pogorelko G. V., Tarasov V. A. (2009). Identification of ICE2 a gene involved in cold acclimation which determines freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Gene 429 98–103. 10.1016/j.gene.2008.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge L. F., Chao D. Y., Shi M., Zhu M. Z., Gao J. P., Lin H. X. (2008). Overexpression of the trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase gene OsTPP1 confers stress tolerance in rice and results in the activation of stress responsive genes. Planta 228 191–201. 10.1007/s00425-008-0729-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakata M., Kuroda M., Ohsumi A., Hirose T., Nakamura H., Muramatsu M., et al. (2012). Overexpression of a rice TIFY gene increases grain size through enhanced accumulation of carbohydrates in the stem. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 76 2129–2134. 10.1271/bbb.120545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M., Kim C. Y., Lee J., Lee S. K., Jeon J. S. (2014). OsWRKY42 represses OsMT1d and induces reactive oxygen species and leaf senescence in rice. Mol. Cells 37 532–539. 10.14348/molcells.2014.0128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong W. J., Yoo Y. H., Park S. A., Moon S., Kim S. R., An G., et al. (2017). Genome-wide identification and extensive analysis of rice-endosperm preferred genes using reference expression database. J. Plant Biol. 60 249–258. 10.1007/s12374-016-0552-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Sun S., Xu D., Lan H., Sun H., Wang Z., et al. (2012). A TFIIIA-type zinc finger protein confers multiple abiotic stress tolerances in transgenic rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Mol. Biol. 80 337–350. 10.1007/s11103-012-9955-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Sun S. J., Xu D. Q., Yang X., Bao Y. M., Wang Z. F., et al. (2009). Increased tolerance of rice to cold, drought and oxidative stresses mediated by the overexpression of a gene that encodes the zinc finger protein ZFP245. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 389 556–561. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Yang X., Wang M. M., Tang H. J., Ding L. Y., Shen Y., et al. (2007). A novel rice C2H2-type zinc finger protein lacking DLN-box/EAR-motif plays a role in salt tolerance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1769 220–227. 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2007.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro S., Nakamura K. (1994). Characterization of a cDNA encoding a novel DNA-binding protein, SPF1 that recognizes SP8 sequences in the 5’ upstream regions of genes coding for sporamin and β-amylase from sweet potato. Mol. Gen. Genet. 244 563–571. 10.1007/BF00282746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y., Katsura K., Maruyama K., Taji T., Kobayashi M., Seki M., et al. (2006). Functional analysis of rice DREB1/CBF-type transcription factors involved in cold-responsive gene expression in transgenic rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 47 141–153. 10.1093/pcp/pci230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto M., Higo K., Takano M. (2009). Circadian clock- and phytochrome-regulated Dof-like gene, Rdd1 is associated with grain size in rice. Plant Cell Environ. 3 592–603. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.01954.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H. J., Jung K. H. (2015). Rice tissue-specific promoters and condition-dependent promoters for effective translational application. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 57 913–924. 10.1111/jipb.12362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J. H., Seo P. J., Park C. M. (2012). The E3 ubiquitin ligase HOS1 regulates Arabidopsis flowering by mediating CONSTANS degradation under cold stress. J. Biol. Chem. 287 43277–43287. 10.1074/jbc.M112.394338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung K. H., An G. (2012). Application of MapMan and RiceNet drives systematic analyses of the early heat stress transcriptome in rice seedlings. J. Plant Biol. 55 436–449. 10.1007/s12374-012-0270-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jung K. H., An G., Ronald P. C. (2008b). Towards a better bowl of rice: assigning function to tens of thousands of rice genes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9 91–101. 10.1038/nrg2286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung K. H., Dardick C., Bartley L. E., Cao P., Phetsom J., Canlas P., et al. (2008a). Refinement of light-responsive transcript lists using rice oligonucleotide arrays: evaluation of gene-redundancy. PLoS ONE 3:e3337 10.1371/journal.pone.0003337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung K. H., Han M. J., Lee D. Y., Lee Y. S., Schreiber L., Franke R., et al. (2006). Wax-deficient anther1 is involved in cuticle and wax production in rice anther walls and is required for pollen development. Plant Cell 18 3015–3032. 10.1105/tpc.106.042044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung K. H., Han M. J., Lee Y. S., Kim Y. W., Hwang I., Kim M. J., et al. (2005). Rice Undeveloped Tapetum1 is a major regulator of early tapetum development. Plant Cell 17 2705–2722. 10.1105/tpc.105.034090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung K. H., Kim S. R., Giong H. K., Nguyen M. X., Koh H. J., An G. (2015). Genome-wide identification and functional analysis of genes expressed ubiquitously in rice. Mol. Plant 8 276–289. 10.1016/j.molp.2014.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneda T., Taga Y., Takai R., Iwano M., Matsui H., Takayama S., et al. (2009). The transcription factor OsNAC4 is a key positive regulator of plant hypersensitive cell death. EMBO J. 28 926–936. 10.1038/emboj.2009.39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasuga M., Miura S., Shinozaki K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. (2004). A combination of the Arabidopsis DREB1A gene and stress-inducible rd29A promoter improved drought- and low-temperature stress tolerance in tobacco by gene transfer. Plant Cell Physiol. 45 346 10.1093/pcp/pch037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C. Y., Vo K. T. X., Nguyen C. D., Jeong D. H., Lee S. K., Kumar M., et al. (2016). Functional analysis of a cold-responsive rice WRKY gene, OsWRKY71. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 10 13–23. 10.1007/s11816-015-0383-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kiribuchi K., Sugimori M., Takeda M., Otani T., Okada K., Onodera H., et al. (2004). RERJ1 a jasmonic acid-responsive gene from rice, encodes a basic helix-loop-helix protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 325 857–863. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koiwai H., Tagiri A., Katoh S., Katoh E., Ichikawa H., Minami E., et al. (2007). RING-H2 type ubiquitin ligase EL5 is involved in root development through the maintenance of cell viability in rice. Plant J. 51 92–104. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03120.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo T., Makita N., Kojima M., Tokunaga H., Sakakibara H. (2012). Cytokinin activity of cis-zeatin and phenotypic alterations induced by overexpression of putative cis-zeatin-O-glucosyltransferase in rice. Plant Physiol. 160 319–331. 10.1104/pp.112.196733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M., Choi J., An G., Kim S.-R. (2017). Ectopic expression of OsSta2 enhances salt stress tolerance in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 8:316 10.3389/fpls.2017.00316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M., Lee S. C., Kim J. Y., Kim S. J., Aye S. S., Kim S. R. (2014). Over-expression of dehydrin gene, OsDhn1 improves drought and salt stress tolerance through scavenging of reactive oxygen species in rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Plant Biol. 57 383–393. 10.1007/s12374-014-0487-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon Y. I., Abe K., Osakabe K., Endo M., Nishizawa-Yokoi A., Saika H., et al. (2012). Overexpression of OsRecQl4 and/or OsExo1 enhances DSB-induced homologous recombination in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 53 2142–2152. 10.1093/pcp/pcs155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.-C., Kim J.-Y., Kim S.-H., Kim S.-J., Lee K., Han S.-K., et al. (2004). Trapping and characterization of cold-responsive genes from T-DNA tagging lines in rice. Plant Sci. 166 69–79. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2003.08.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li F., Guo S., Zhao Y., Chen D., Chong K., Xu Y. (2010). Overexpression of a homopeptide repeat-containing bHLH protein gene (OrbHLH001) from Dongxiang wild rice confers freezing and salt tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 29 977–986. 10.1007/s00299-010-0883-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Xue H. W. (2007). Arabidopsis PLD zeta 2 regulates vesicle trafficking and is required for auxin response. Plant Cell 19 281–295. 10.1105/tpc.106.041426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P., Chen F., Quan C., Zhang G. Y. (2005). OsDREB1 gene from rice enhances cold tolerance in tobacco. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 10 478–483. 10.1016/S1007-0214(05)70103-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Wu Y., Wang X. (2012). bZIP transcription factor OsbZIP52/RISBZ5: a potential negative regulator of cold and drought stress response in rice. Planta 235 1157–1169. 10.1007/s00425-011-1564-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Bai X., Wang X., Chu C. (2007). OsWRKY71 a rice transcription factor, is involved in rice defense response. J. Plant Physiol. 164 969–979. 10.1016/j.jplph.2006.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Xu Y., Xiao J., Ma Q., Li D., Xue Z., et al. (2011). OsDOG, a gibberellin-induced A20/AN1 zinc-finger protein, negatively regulates gibberellin-mediated cell elongation in rice. J. Plant Physiol. 168 1098–1105. 10.1016/j.jplph.2010.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo S. F., Yang S. Y., Chen K. T., Hsing Y. I., Zeevaart J. A., Chen L. J., et al. (2008). A novel class of gibberellin 2-oxidases control semidwarfism, tillering, and root development in rice. Plant Cell 20 2603–2618. 10.1105/tpc.108.060913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]