Abstract

Key points

Angiotensin II (AngII) is crucial in cardiovascular regulation in perinatal mammalians.

Here we show that AngII increases twitch Ca2+ transients of mouse immature but not mature cardiomyocytes by robustly activating CaV1.2 L‐type Ca2+ channels through a novel signalling pathway involving angiotensin type 1 (AT1) receptors, β‐arrestin2 and casein kinase 2.

A β‐arrestin‐biased AT1 receptor agonist, TRV027, was as effective as AngII in activating L‐type Ca2+ channels.

Our results help understand the molecular mechanism by which AngII regulates the perinatal circulation and also suggest that β‐arrestin‐biased AT1 receptor agonists may be valuable therapeutics for paediatric heart failure.

Abstract

Angiotensin II (AngII), the main effector peptide of the renin–angiotensin system, plays important roles in cardiovascular regulation in the perinatal period. Despite the well‐known stimulatory effect of AngII on vascular contraction, little is known about regulation of contraction of the immature heart by AngII. Here we found that AngII significantly increased the peak amplitude of twitch Ca2+ transients by robustly activating L‐type CaV1.2 Ca2+ (CaV1.2) channels in mouse immature but not mature cardiomyocytes. This response to AngII was mediated by AT1 receptors and β‐arrestin2. A β‐arrestin‐biased AT1 receptor agonist was as effective as AngII in activating CaV1.2 channels. Src‐family tyrosine kinases (SFKs) and casein kinase 2α’β (CK2α’β) were sequentially activated when AngII activated CaV1.2 channels. A cyclin‐dependent kinase inhibitor, p27Kip1 (p27), inhibited CK2α’β, and AngII removed this inhibitory effect through phosphorylating tyrosine 88 of p27 via SFKs in cardiomyocytes. In a human embryonic kidney cell line, tsA201 cells, overexpression of CK2α’β but not c‐Src directly activated recombinant CaV1.2 channels composed of C‐terminally truncated α1C, the distal C‐terminus of α1C, β2C and α2δ1 subunits, by phosphorylating threonine 1704 located at the interface between the proximal and the distal C‐terminus of CaV1.2α1C subunits. Co‐immunoprecipitation revealed that CaV1.2 channels, CK2α’β and p27 formed a macromolecular complex. Therefore, stimulation of AT1 receptors by AngII activates CaV1.2 channels through β‐arrestin2 and CK2α’β, thereby probably exerting a positive inotropic effect in the immature heart. Our results also indicated that β‐arrestin‐biased AT1 receptor agonists may be used as valuable therapeutics for paediatric heart failure in the future.

Keywords: angiotensin II, CaV1.2 Ca2+ channels, cardiomyocytes

Key points

Angiotensin II (AngII) is crucial in cardiovascular regulation in perinatal mammalians.

Here we show that AngII increases twitch Ca2+ transients of mouse immature but not mature cardiomyocytes by robustly activating CaV1.2 L‐type Ca2+ channels through a novel signalling pathway involving angiotensin type 1 (AT1) receptors, β‐arrestin2 and casein kinase 2.

A β‐arrestin‐biased AT1 receptor agonist, TRV027, was as effective as AngII in activating L‐type Ca2+ channels.

Our results help understand the molecular mechanism by which AngII regulates the perinatal circulation and also suggest that β‐arrestin‐biased AT1 receptor agonists may be valuable therapeutics for paediatric heart failure.

Abbreviations

- ACM

atrial cardiomyocyte

- AKAP

A‐kinase anchoring protein

- AngII

angiotensin II

- AT1

angiotensin type 1 receptor

- AT2

angiotensin type 2 receptor

- AVCM

adult ventricular cardiomyocyte

- CaV1.2 channel

L‐type CaV1.2 Ca2+ channel

- CaV1.2α1CΔ1821

CaV1.2α1c subunit devoid of its distal C‐terminus1822–2171

- CDK

cyclin‐dependent kinase

- CK2

casein kinase 2

- CSK

C‐terminal Src kinase

- DCRD

the distal C‐terminus regulatory domain

- DCT

the distal C‐terminus1822–2171

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- E

embryonic day

- Erev

reversal potential

- FL

full‐length

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- HA

hemagglutinin

- IB

immunoblotting

- IP

immunoprecipitation

- NVCM

neonatal ventricular cardiomyocyte

- PCRD

the proximal C‐terminal regulatory domain

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PKC

protein kinase C

- P

postnatal day

- p27

p27Kip1

- RAS

renin–angiotensin system

- RFP

red fluorescent protein

- SFK

Src‐family tyrosine kinase

- shRNA

small hairpin RNA

Introduction

The renin–angiotensin system (RAS) is an important regulator of the cardiovascular system and controls sodium balance, body fluid volumes and arterial pressure (Hall, 2003; Paul et al. 2006; Karnik et al. 2015). Classically, RAS was viewed as an endocrinological system (Hall, 2003). The enzyme renin secreted from juxtaglomerular cells in the kidney digests angiotensinogen produced by the liver to a decapeptide, angiotensin I, in the plasma. Angiotensin I is then converted to an octapeptide, angiotensin II (AngII), by the angiotensin‐converting enzyme in the pulmonary circulation. AngII is a major player in this system and activates two specific G‐protein‐coupled receptors, angiotensin type 1 (AT1) and angiotensin type 2 (AT2) receptors (Hunyady & Catt, 2006; Karnik et al. 2015). AT1 receptors mediate most of the known effects of AngII, whereas the functional role of AT2 receptors is still under extensive investigation. AT1 receptors activate various heterotrimeric G proteins (Gq/11, G12/13 and Gi) and β‐arrestins. Although β‐arrestins were originally discovered to desensitize activated G‐protein‐coupled receptors, it is now well established that β‐arrestins mediate G‐protein‐independent signals on their own right (Shukla et al. 2011). In addition to the plasma RAS, many tissues, including the heart, possess many components of RAS and produce AngII in situ to regulate their own functions (local RAS) (Paul et al. 2006; Bader, 2010). RAS also plays significant roles in cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension, atherosclerosis, and cardiac hypertrophy and failure as evidenced by the fact that inhibitors of the angiotensin‐converting enzyme and AT1 receptors significantly improve the outcome of these diseases (Jong et al. 2003; Pfeffer et al. 2003).

In fetal and postnatal development, the plasma and local RAS are extremely important (Heymann et al. 1981; Paul et al. 2006). In general, all components of RAS begin to be expressed early in fetal development, and their amounts culminate at the perinatal period. Indeed, the plasma renin concentration and activity are higher in newborns than adults in various animals, including humans (Wallace et al. 1980; Varga et al. 1981). At the time of birth, neonates experience major haemodynamic changes such as rapid increase in pulmonary blood flow, removal of placental circulation, closure of several sites of shunting within the heart and great vessels, and changes in cardiac output and its distribution (Hooper et al. 2015). Left ventricular output increases as much as ∼3 times at birth, and the systemic blood pressure increases immediately after birth and continues to rise for several weeks, concomitant with an increase in systemic vascular resistance. RAS together with the sympathetic nervous system is thought to play a critical role in these changes (Heymann et al. 1981). Furthermore, infants born vaginally have higher circulating concentrations of AngII than those delivered by caesarean section (Lumbers & Reid, 1977), and a minor degree of haemorrhage results in a marked increase in plasma AngII concentration (Broughton Pipkin et al. 1974), indicating that RAS is critical for newborns’ response to haemodynamic insults. Indeed, mice deficient of angiotensinogen or AT1 receptors exhibit ∼50% perinatal lethargy (Kim et al. 1995; Oliverio et al. 1998).

Although it is well established that AngII causes vascular contraction, little is known about the effect of AngII on contraction of the immature heart. Herein, we have highlighted that AngII markedly increases twitch Ca2+ transients of immature but not mature cardiomyocytes by robustly increasing L‐type CaV1.2 Ca2+ (CaV1.2) channel currents through a novel pathway composed of AT1 receptors, β‐arrestin2 and casein kinase 2 (CK2). Thus, β‐arrestin‐biased AT1 receptor agonists, which have not only a positive inotropic effect but also an anti‐apoptotic effect on cardiomyocytes, may be used as valuable therapeutics for paediatric heart failure in the future (Kim et al. 2012).

Methods

Ethical approval

All animals used in this study received humane care in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health. All experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with the Guidelines for Animal Experimentation of Shinshu University and approved by the Committee for Animal Experimentation (Approval numbers 250062 and 280035). All mice were given free access to water and standard diet throughout the study, and maintained in a temperature‐ (21–26°C) and humidity‐ (50–60%) controlled room with a 12 h light/dark cycle. All experimental mice were deeply anaesthetized with 0.3 mg kg–1 medetomidine (Domitor, Nippon Zenyaku Kogyo Co., Fukushima, Japan), 4.0 mg kg–1 midazolam (Midazolam Sandoz, Novartis, Tokyo, Japan) and 5.0 mg kg–1 butorphanol (Vetorphale, Meiji Seika Pharma Co., Tokyo, Japan), i.p., or isoflurane (Escain, Mylan Seiyaku, Osaka, Japan) inhalation (mouse pups). We conform to the principles and standards for reporting animal experiments in The Journal of Physiology and Experimental Physiology (Grundy, 2015). All C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Japan SLC Inc.

Isolation of cardiomyocytes

Cardiomyocytes from male C57BL/6 mice at postnatal days (P) 10, P28–34 and P56–62 were enzymatically isolated as previously described (Horiuchi‐Hirose et al. 2011). Briefly, the hearts were removed from anaesthetized mice, mounted on the Langendorff apparatus with modified Tyrode solution containing (mm) 136.5 NaCl (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan), 5.4 KCl (Wako), 1.8 CaCl2 (Wako), 0.53 MgCl2 (Wako), 5.5 Hepes (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) and 5.5 glucose (Wako) (pH 7.4 with NaOH), and digested with Ca2+‐free Tyrode solution containing 0.80 mg ml–1 collagenase (Nitta Gelatin Inc., Osaka, Japan), 0.06 mg ml–1 protease (Sigma‐Aldrich, Tokyo, Japan), 1.20 mg ml–1 hyaluronidase (Sigma‐Aldrich), 0.03 mg ml–1 DNase I (Roche, Tokyo, Japan) and 0.50 mg ml–1 BSA (Wako) at 37°C for 2 min. Isolated cardiomyocytes were suspended in Ca2+‐free Tyrode solution containing 1 mg ml–1 BSA at room temperature, and the Ca2+ concentration was gradually increased to 1.8 mm. After that, cardiomyocytes were treated with vehicle (deionized water) or AngII (Sigma‐Aldrich).

Cell cultures and preparations

Anaesthetized neonatal (P0 or P1) C57BL/6 mice were decapitated and hearts were then removed aseptically. Primary cultures of cardiomyocytes were prepared from the hearts by using the Neonatal Cardiomyocyte Isolation System (Worthington Biochemical Corp., Lakewood, NJ, USA). To enrich cardiomyocytes, the collected cells were plated onto plastic culture dishes in low‐glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) plus GlutaMAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units ml–1 penicillin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 100 μg ml–1 streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 60 min and then plated onto gelatin‐ (Difco, Becton, Dickinson Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and fibronectin‐ (Sigma‐Aldrich) coated glass bottom dishes or coverslips. After culture in serum‐free medium for 24 h, the cardiomyocytes were treated with vehicle (deionized water) or AngII. We confirmed that these cardiomyocytes soon after isolation and those cultured for a few days exhibited almost the same degree of response of L‐type Ca2+ channels to AngII.

HL‐1 cardiomyocytes were kindly provided by Dr William C. Claycomb (Louisiana State University Health Science Centre, New Orleans, LA, USA) and were cultured in Claycomb Medium (Sigma‐Aldrich) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma‐Aldrich), 100 units ml–1 penicillin, 100 μg ml–1 streptomycin, 2 mm l‐glutamine (Sigma‐Aldrich) and 100 μm noradrenaline (Sigma‐Aldrich) at 37°C and 5% CO2 on gelatin/fibronectin‐coated flasks (Claycomb et al. 1998). HL‐1 cardiomyocytes spontaneously beating were passaged when they reached 100% confluency. For electrophysiological experiments, HL‐1 cardiomyocytes were plated onto gelatin/fibronectin‐coated coverslips at low density. After culture in noradrenaline‐ and serum‐free Claycomb medium for 24 h, HL‐1 cardiomyocytes were treated with vehicle (deionized water) or AngII.

For introduction of small hairpin (sh) RNAs with red fluorescent protein (RFP) or cDNA of C‐terminal Src kinase (CSK) with green fluorescent protein (GFP) in HL‐1 cardiomyocytes, lentiviral stocks were produced in HEK293T cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) by cotransfection of the packaging plasmids pMD.G (VSVG envelope), pMDLg/pRRE (gag‐pol plasmid) and pRSV‐Rev (rev plasmid) with corresponding lentiviral constructs using polyethylenimine (Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, PA, USA) and concentrated by polybrene (Sigma‐Aldrich) (Kojima et al. 2014). Whole‐cell patch‐clamp recordings were performed with RFP‐ or GFP‐positive cells.

TsA201 human embryonic kidney cells (European Collection of Authenticated Cell, Salisbury, UK) were cultured in low‐glucose DMEM plus GlutaMAX, 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units ml–1 penicillin and 100 μg ml–1 streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2. TsA201 cells were grown to ∼70% confluency in plastic dishes and transiently transfected with an equimolar ratio of cDNA encoding CaV1.2 α1c, β2c and α2δ1 subunits (1.0, 0.7, and 0.8 μg of plasmid DNA per 35 mm dish, respectively) and other proteins by the calcium phosphate method. For electrophysiological experiments, a 10‐fold lower ratio of cDNA encoding enhanced GFP (EGFP) was added to each transfection mixture as an indicator of successful transfection, and 30 h after transfection, cells were plated onto collagen‐ (Nitta gelatin) coated coverslips at low density. Experiments were performed with 48–56 h post‐transfection cells.

Plasmid construction

The cDNA encoding rabbit α1C was generously given by Dr William A. Catterall (University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA). CaV1.2α1CΔ1821 [CaV1.2α1c subunit devoid of its distal C‐terminus1822–2171 (DCT)] was generated by PCR using antisense primers containing a stop codon and SalI restriction site. All primer sequences used in this study are listed in Table 1. The PCR products were subcloned into a blunt‐ended pBlueScript SK‐ vector and again subcloned into the EcoRV/SalI site of the CaV1.2α1C subunit. For immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation assays, hemagglutinin (HA)‐tagged CaV1.2α1C and HA‐CaV1.2α1CΔ1821 were used. An HA‐epitope was inserted into the extracellular loop between S5 and S6 in domain II as previously described (Nakada et al. 2012). To generate HA‐CaV1.2α1CDCT and 3xFLAG‐tagged CaV1.2α1CDCT, the cDNA encoding amino acids 1822–2171 of CaV1.2α1C was amplified by PCR and then subcloned into pCMV‐HA (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) or p3xFLAG‐CMV‐10 (Sigma‐Aldrich).

Table 1.

List of oligonucleotides used in this study

| Construct | Backbone | Direction | Sequence (5’→3’) | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaV1.2α1CΔ1821 | pcDNA3 | S | AATCCAGCTGAACATACCCAATGCT | EcoRV/SalI*1 |

| AS | AGGTCGACCTACACAGTGCTGACTGTGCTG | |||

| CaV1.2α1CΔ1821T1704A | pcDNA3 | S | TCTCCGGAGACCTGGCAGCTGAGGAAGAG | Mutagenesis*2 |

| AS | CTCTTCCTCAGCTGCCAGGTCTCCGGAGA | |||

| FLAG‐CaV1.2α1CDCT | p3xFLAG‐CMV‐10 | S | CGAATTCCGTGGAGGGCCACGGGTCCCCC | EcoRV/BamHI*1 |

| AS | GGATCCCGCTACAGGCTGCTGACGCCGGC | |||

| HA‐CaV1.2α1CDCT | pCMV‐HA | S | CAGTCGACTGTGGAGGGCCACGGGTCCCCC | SalI/NotI*1 |

| AS | GGCGGCCGCCTACAGGCTGCTGACGCCGGC | |||

| CaVβ2c | pcDNA3.1 | S | CACTGAGAACCTCCGATCGT | |

| AS | GCTTGTACTAGGCCAATTTCTGT | |||

| CaVα2δ1 | pcDNA3.1 | S | TGATCTTCGATCGCGAAGATGG | |

| AS | AGGGCATGGAATTAAGTTGCAGA | |||

| Myc‐c‐Src | pCMV‐Myc | S | TAGCCCGGGCGGATCCAGCCAGGACCATGGGCAG | In fusion*3 |

| AS | GCTTGATATCGAATTCTAGGTTCTCCCCGGGCTG | |||

| CK2α | pcDNA3.1 | S | AAGTTCAGCTTTGTCTGTCAAC | |

| AS | CTGCTCAGGCATCAGAAGG | |||

| CK2α′ | pcDNA3.1 | S | CGTCCCTCCGGCAGCCGAA | |

| AS | ACGTGATCTCGCTACACGCGTTAAGAC | |||

| CK2β | pcDNA3.1 | S | TTTTGCGCTGTAGTGGTCTC | |

| AS | CCATAGACTTCCTGAAAGGGTG | |||

| FLAG‐CK2α′ | p3xFLAG‐CMV‐10 | S | CGGTACCGCCCGGCCCGGCCGCGGGCAGTC | KpnI/BamHI*1 |

| AS | TGGATCCACAGACCGTCGATTCCCCAGGCT | |||

| FLAG‐CK2β | p3xFLAG‐CMV‐10 | S | CGGTACCGAGTAGCTCTGAGGAGGTGTCCT | KpnI/BamHI*1 |

| AS | GGGATCCCAGAGGGAGAGGTGGGTGGGCAA | |||

| Myc‐p27 WT | pCMV‐Myc | S | CAGAATTCTGTCAAACGTGAGAGTGTCTAA | EcoRI/XhoI*1 |

| AS | AACTCGAGTTACGTCTGGCGTCGAAGGCCG | |||

| Myc‐p27 Y88F | pCMV‐Myc | S | TTGCCCGAGTTCTTCTACAGGCCCCCG | Mutagenesis*2 |

| AS | CGGGGGCCTGTAGAAGAACTCGGGCAA | |||

| Myc‐p27 Y88E | pCMV‐Myc | S | CTTGCCCGAGTTCGAGTACAGGCCCCCGC | Mutagenesis*2 |

| AS | GCGGGGGCCTGTACTCGAACTCGGGCAAG | |||

| sh‐Gq#1 | pRSI9‐U6‐(sh)‐UbiC‐TagRFP‐2A‐Puro | S | ACCGGGCCCTCTTGTAGTTTCTTTATGTTAATATTCATAGCATAAAGAAGCTACAAGAGGGCTTTTTTG | shRNA*4 |

| AS | CGAACAAAAAAGCCCTCTTGTAGCTTCTTTATGCTATGAATATTAACATAAAGAAACTACAAGAGGGCC | |||

| sh‐Gq#2 | pRSI9‐U6‐(sh)‐UbiC‐TagRFP‐2A‐Puro | S | ACCGGCCTTCCTATCTGTCTACATAAGTTAATATTCATAGCTTGTGTAGGCAGATAGGAAGGTTTTTTG | shRNA*4 |

| AS | CGAACAAAAAACCTTCCTATCTGCCTACACAAGCTATGAATATTAACTTATGTAGACAGATAGGAAGGC | |||

| sh‐G11#1 | pRSI9‐U6‐(sh)‐UbiC‐TagRFP‐2A‐Puro | S | GCACCGGGCTCAAGATCCTCTATAAGTAGTTAATATTCATAGCTACTTGTAGAGGATCTTGAGCTTTTT | shRNA*4 |

| AS | CGAACAAAAAAGCTCAAGATCCTCTACAAGTAGCTATGAATATTAACTACTTATAGAGGATCTTGAGCC | |||

| sh‐G11#2 | pRSI9‐U6‐(sh)‐UbiC‐TagRFP‐2A‐Puro | S | ACCGGCCTCTACAAGTATGAGTAGAAGTTAATATTCATAGCTTCTGCTCATACTTGTAGAGGTTTTTTG | shRNA*4 |

| AS | CGAACAAAAAACCTCTACAAGTATGAGCAGAAGCTATGAATATTAACTTCTACTCATACTTGTAGAGGC | |||

| sh‐β‐arrestin1#1 | pRSI9‐U6‐(sh)‐UbiC‐TagRFP‐2A‐Puro | S | ACCGGCCTTGAGGTATCATTGGATAAGTTAATATTCATAGCTTATCCAGTGATGCCTCAAGGTTTTTTG | shRNA*4 |

| AS | CGAACAAAAAACCTTGAGGCATCACTGGATAAGCTATGAATATTAACTTATCCAATGATACCTCAAGGC | |||

| sh‐β‐arrestin1#2 | pRSI9‐U6‐(sh)‐UbiC‐TagRFP‐2A‐Puro | S | ACCGGCCAATGATGACGATATTGTATGTTAATATTCATAGCATACAATGTCGTCATCATTGGTTTTTTG | shRNA*4 |

| AS | CGAACAAAAAACCAATGATGACGACATTGTATGCTATGAATATTAACATACAATATCGTCATCATTGGC | |||

| sh‐β‐arrestin2#1 | pRSI9‐U6‐(sh)‐UbiC‐TagRFP‐2A‐Puro | S | ACCGGCGGCTTATCATTAGAAAGGTAGTTAATATTCATAGCTACCTTTCTGATGATAAGCCGTTTTTTG | shRNA*4 |

| AS | CGAACAAAAAACGGCTTATCATCAGAAAGGTAGCTATGAATATTAACTACCTTTCTAATGATAAGCCGC | |||

| sh‐β‐arrestin2#2 | pRSI9‐U6‐(sh)‐UbiC‐TagRFP‐2A‐Puro | S | ACCGGGACTATTTGAAGGACTGGAAAGTTAATATTCATAGCTTTCCGGTCCTTCAAGTAGTCTTTTTTG | shRNA*4 |

| AS | CGAACAAAAAAGACTACTTGAAGGACCGGAAAGCTATGAATATTAACTTTCCAGTCCTTCAAATAGTCC | |||

| sh‐CK2α#1 | pRSI9‐U6‐(sh)‐UbiC‐TagRFP‐2A‐Puro | S | ACCGGGCCAATATGATGTTAGGGATTGTTAATATTCATAGCAATCCCTGACATCATATTGGCTTTTTTG | shRNA*4 |

| AS | CGAACAAAAAAGCCAATATGATGTCAGGGATTGCTATGAATATTAACAATCCCTAACATCATATTGGCC | |||

| sh‐CK2α#2 | pRSI9‐U6‐(sh)‐UbiC‐TagRFP‐2A‐Puro | S | ACCGGCCGAGTTGCTTCTTGATATTTGTTAATATTCATAGCAAATATCGAGAAGCAACTCGGTTTTTTG | shRNA*4 |

| AS | CGAACAAAAAACCGAGTTGCTTCTCGATATTTGCTATGAATATTAACAAATATCAAGAAGCAACTCGGC | |||

| sh‐CK2α′#1 | pRSI9‐U6‐(sh)‐UbiC‐TagRFP‐2A‐Puro | S | ACCGGCGTGGTGGAACAAATATTATTGTTAATATTCATAGCAATGATATTTGTTCCACCACGTTTTTTG | shRNA*4 |

| AS | CGAACAAAAAACGTGGTGGAACAAATATCATTGCTATGAATATTAACAATAATATTTGTTCCACCACGC | |||

| sh‐CK2α′#2 | pRSI9‐U6‐(sh)‐UbiC‐TagRFP‐2A‐Puro | S | ACCGGAGACCTAGATCCACATTTCAAGTTAATATTCATAGCTTGAAGTGTGGATCTAGGTCTTTTTTTG | shRNA*4 |

| AS | CGAACAAAAAAAGACCTAGATCCACACTTCAAGCTATGAATATTAACTTGAAATGTGGATCTAGGTCTC | |||

| sh‐CK2β#1 | pRSI9‐U6‐(sh)‐UbiC‐TagRFP‐2A‐Puro | S | ACCGGTGGTTTCCCTTACATGTTCTTGTTAATATTCATAGCAAGAGCATGTGAGGGAAACCATTTTTTG | shRNA*4 |

| AS | CGAACAAAAAATGGTTTCCCTCACATGCTCTTGCTATGAATATTAACAAGAACATGTAAGGGAAACCAC | |||

| sh‐CK2β#2 | pRSI9‐U6‐(sh)‐UbiC‐TagRFP‐2A‐Puro | S | ACCGGCACATGCTCTTTATGGTGTATGTTAATATTCATAGCATGCACCATGAAGAGCATGTGTTTTTTG | shRNA*4 |

| AS | CGAACAAAAAACACATGCTCTTCATGGTGCATGCTATGAATATTAACATACACCATAAAGAGCATGTGC | |||

| sh‐p27#1 | pRSI9‐U6‐(sh)‐UbiC‐TagRFP‐2A‐Puro | S | ACCGGCGCAAGTGGAGTTTCGGCTTTGTTAATATTCATAGCAAAGTCGAAATTCCACTTGCGTTTTTTG | shRNA*4 |

| AS | CGAACAAAAAACGCAAGTGGAATTTCGACTTTGCTATGAATATTAACAAAGCCGAAACTCCACTTGCGC | |||

| sh‐p27#2 | pRSI9‐U6‐(sh)‐UbiC‐TagRFP‐2A‐Puro | S | ACCGGCCGGTATTTGGTGGACTAAATGTTAATATTCATAGCATTTGGTCCACCAAATGCCGGTTTTTTG | shRNA*4 |

| AS | CGAACAAAAAACCGGCATTTGGTGGACCAAATGCTATGAATATTAACATTTAGTCCACCAAATACCGGC | |||

| CSK (lentivirus) | CSII‐EF‐MCS‐IRES‐hrGFP | S | GCAGAAGATGTCGGCAATACAG | |

| AS | GCCGGCTGGGGCTCAGTTCAA |

* 1PCR products were subcloned into the expression vectors after digestion with the restriction enzymes indicated. * 2Primers used for the quickchange site‐directed mutagenesis system. * 3PCR products were subcloned into the expression vectors by an in‐fusion cloning system. * 4Sense and antisense oligonucleotides were annealed and subcloned into the shRNA lentivector linearized with BbsI.

The cDNAs of CaVβ2c and CaVα2δ1 subunits were isolated with RT‐PCR from a rat heart cDNA library. The cDNAs of CK2α, CK2α’, CK2β, p27Kip1 (p27), c‐Src and CSK were isolated with RT‐PCR from a mouse heart cDNA library. These cDNAs were subcloned into pcDNA3.1, pCMV‐HA, pCMV‐Myc (Clontech) or p3xFLAG‐CMV‐10. Single amino acid substitution mutants [CaV1.2α1CΔ1821T1704A (Thr1704 of α1C was substituted with alanine), Myc‐p27Y88F (Tyr88 of p27 was substituted with phenylalanine, Y88F), and Myc‐p27Y88E (Tyr88 of p27 was substituted with glutamic acid)] were generated with the QuickChange Site‐Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, Agilent Technologies, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The cDNAs of CSK were isolated with RT‐PCR from a mouse heart cDNA library and then subcloned into lentiviral transfer plasmid CSII‐EF‐MCS‐IRES‐hrGFP [kindly provided by Dr Hiroyuki Miyoshi (RIKEN BRC, Tsukuba, Japan)]. To prepare the shRNA expression vectors for p27, Gq, G11, β‐arrestin1, β‐arrestin2, CK2α, CK2α’ and CK2β, the double stranded DNA oligo encoding a sense–loop–antisense sequence to the targeted genes was inserted into lentiviral shRNA expression vector pRSI9‐U6‐(sh)‐UbiC‐TagRFP‐2A‐Puro (Addgene, Cambridge, MA, USA). All DNA oligo sequences used in this study are listed in Table 1.

Antibodies

Antibodies against the following proteins were used: CaV1.2α1c (1:2000, ACC‐003, Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel), α‐tubulin (1:3000, T5168, Sigma‐Aldrich), Gq/11 (1:500, sc‐392, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), β‐arrestin1 (1:1000, 610550, BD Transduction Laboratories, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), β‐arrestin2 (1:2000, ab167047, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), CSK (1:1000, H00001445‐M01, Abnova, Taipei, Taiwan), CK2β (1:1000, MAB0817, Abnova), HA (1:10 000, M180‐3, MBL, Nagoya, Japan), Myc (1:10 000, M192‐3, MBL), control mouse IgG2b (M077‐3, MBL), FLAG (1:5000, F1804, Sigma‐Aldrich), p27 (1:5000, 610241, BD Transduction), p27‐pTyr88 (1:2000, AP20721b, Abgent, San Diego, CA, USA), mouse or rabbit IgG (1:30 000, 715‐036‐150 or 111‐035‐006, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA), and mouse IgG TrueBlot Ultra (1:2000, 18‐8817‐31, Rockland, Limerick, PA, USA). Antibodies against the CK2α and CK2α’ subunits were kindly provided by Dr David W. Litchfield (University of Western Ontario, Ontario, Canada).

Ca2+ imaging

The imaging of twitch Ca2+ transients was performed as previously described (Nakada et al. 2012). Briefly, cardiomyocytes in glass bottom dishes were incubated with 6 μm Fluo 4/AM (Dojindo) plus 0.01% Cremophore EL (Sigma‐Aldrich) and 0.02% BSA in serum‐free DMEM for 45 min at 37°C and 5% CO2 followed by de‐esterification. Cardiomyocytes were superfused with modified Tyrode solution at room temperature and paced with 1 ms pulses of 50 V at 0.3 Hz across the 20 mm incubation chamber. Fluorescence images were acquired with an LSM 7 LIVE laser‐scanning microscope with a 20×/0.8 plan apochromatic objective (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Each image was taken with 128 pixels × 128 pixels every 2.8 ms. The time course of Ca2+ transients was assessed from the fluorescence change in individual cardiomyocytes selected by the ROI tool. An increment in fluorescence intensity from baseline was measured and normalized to baseline intensity (ΔF/F 0).

Electrophysiology

Ionic and gating currents of CaV1.2 channels were recorded in the whole‐cell configuration of the patch‐clamp technique at 35–36°C with a patch‐clamp amplifier (Axopatch 200B, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and sampled at 10 kHz after low‐pass filtering at 5 kHz (Horiuchi‐Hirose et al. 2011). Patch pipettes (2–3 MΩ) were fabricated from borosilicate glass capillaries (Kimax‐51, Kimble Glass, Vineland, NJ, USA) and coated with Sylgard 184 (Dow Corning Toray Co., Tokyo, Japan). Series resistance was always kept less than 7 MΩ and routinely compensated for with the amplifier by ∼75%. CaV1.2 channel currents of cardiomyocytes were measured with the intracellular solution containing (mm): 20 TEA‐Cl (Tokyo Chemical Industry, Tokyo, Japan), 100 CsCl, 10 EGTA (Dojindo), 10 Hepes, 1 MgCl2, 5 MgATP and 0.5 MgGTP [pH 7.2 with CsOH (Sigma‐Aldrich)]. The extracellular bath solution contained (mm): 150 TEA‐Cl, 5 CsCl, 5 BaCl2 (Wako), 5 Hepes, 1.2 MgCl2 and 5.5 glucose (pH 7.4 with CsOH). The membrane potential was stepped from the holding potential –80 mV to –45 mV for 1000 ms (to inactivate voltage‐gated Na+ channels and T‐type Ca2+ channels) and then for 300 ms to potentials between –40 and +70 mV with a 10 mV increment every 5 s. Coupling efficiency for recombinant CaV1.2 channels in tsA201 cells was assessed with the intracellular solution containing (mm): 135 CsCl, 10 EGTA, 1 MgCl2, 4 MgATP (pH 7.3 with CsOH). The extracellular bath solution contained (mm): 150 Tris (Wako), 10 BaCl2, 1 MgCl2 and 10 glucose (pH 7.4 with HCl) (Hulme et al. 2006). Gating charge movement was measured by applying a series of test pulses from the holding potential of –80 mV to potentials between +60 mV and +80 mV with a 2 mV increment every 5 s and integrating the ON gating charge for 2 ms from the beginning at the reversal potential of CaV1.2 channels. Ba2+ tail currents were recorded after repolarization to –50 mV from each test pulse.

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation

Cells were lysed with ice‐cold lysis buffer composed of 10 mm Tris pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA (Dojindo), 1% Triton‐X (Sigma‐Aldrich) and 10% glycerol (Wako) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Nacalai tesque, Kyoto, Japan). For analysis of Tyr88 phosphorylation of p27, the lysis buffer with the phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Nacalai tesque) and without EDTA was used. After sonication for 5 s and gentle rocking at 4°C for 30 min, lysates were centrifuged at 10 000 g at 4°C for 30 min in order to remove insoluble materials. In experiments shown in Fig. 7 C, lysates were ultracentrifuged at 100 000 g at 4°C for 1 h to further remove insoluble materials. The protein concentrations of samples were measured by a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For immunoprecipitation, lysates (250 μg) were incubated with antibodies (2 μg) covalently linked to Protein A‐Sepharose or Protein G‐Sepharose (17‐6002‐35, GE Healthcare Japan, Tokyo, Japan) at 4°C for 2 h, and the immunoprecipitates were then extensively washed with lysis buffer.

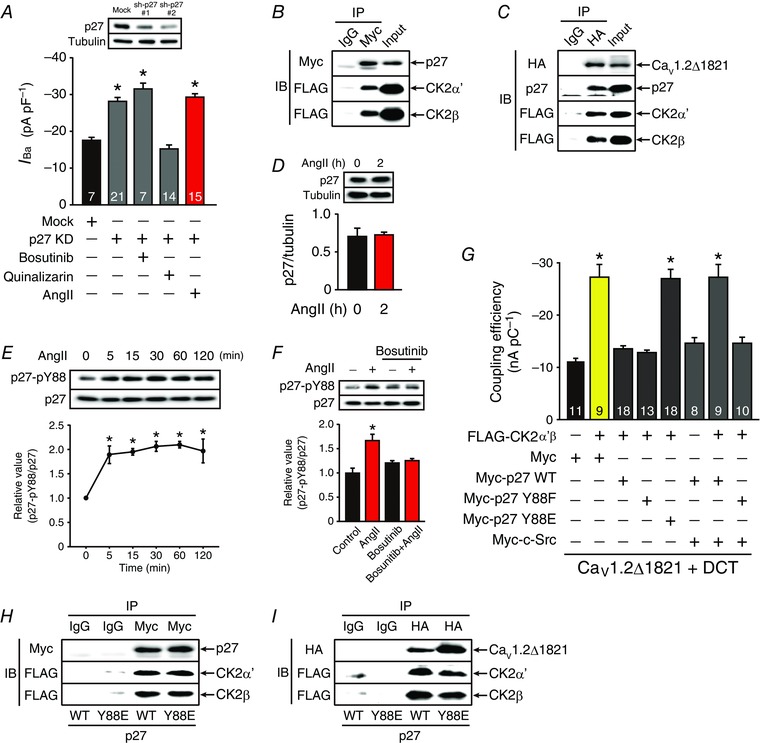

Figure 7. AngII removes the inhibitory effect of p27 on CK2α’β through SFKs and activates CaV1.2 channels.

A, effect of sh‐p27#2 on peak CaV1.2 channel current density at 0 mV in HL‐1 cardiomyocytes in the presence of bosutinib (2 μm), quinalizarin (3 μm) or AngII (3 μm, 2 h). * P < 0.01 versus basal of mock. B and C, p27 bound to CK2α’β with (C) or without (B) CaV1.2Δ1821 channels in tsA201 cells. B, Myc‐p27, FLAG‐CK2α’ and FLAG‐CK2β were expressed in tsA201 cells. C, HA‐CaV1.2Δ1821 channels, Myc‐p27, FLAG‐CK2α’ and FLAG‐CK2β were expressed in tsA201 cells. D, AngII (3 μm, 2 h) did not alter the expression level of p27; n = 3 independent blots. * P < 0.05 versus AngII 0 h group. E, time‐dependent effect of AngII (3 μm) on Tyr88 phosphorylation of p27 (p27‐pY88) in HL‐1 cardiomyocytes; n = 3 independent blots. * P < 0.01 versus AngII 0 min group. F, effect of bosutinib on AngII‐ (3 μm, 2 h) dependent Tyr88 phosphorylation in HL‐1 cardiomyocytes. HL‐1 cardiomyocytes were treated with vehicle or AngII (3 μm) for 2 h in the presence or absence of bosutinib (2 μm) before extraction; n = 4 independent blots. * P < 0.01 versus control in the absence of bosutinib. G, coupling efficiency of CaV1.2Δ1821 + DCT channels in tsA201 cells overexpressing indicated proteins. * P < 0.01 versus CaV1.2Δ1821 + DCT with Myc. The number of observed cells is indicated in the graph (A and G). H and I, effect of p27Y88E on interaction between CK2α’β and p27 (H) and CaV1.2Δ1821 channels (I) in tsA201 cells. H, Myc‐p27 (WT or Y88E), FLAG‐CK2α’ and FLAG‐CK2β were expressed in tsA201 cells. I, HA‐CaV1.2Δ1821 channels, Myc‐p27 (WT or Y88E), FLAG‐CK2α’ and FLAG‐CK2β were expressed in tsA201 cells. IB and IP were performed with indicated antibodies and data are representative of three independent blots (A–F, H and I). In each panel contrast and brightness were adjusted to the whole image to make the features of interest clearer.

For immunoblotting, samples (10–50 μg per lane) were separated on 7.5% or 10% SDS‐PAGE and electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Non‐specific binding was blocked with Blocking One (Nacalai tesque) or Blocking One‐P (Nacalai tesque) for 30 min at room temperature. Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. After being washed with TBST, membranes were reacted with HRP‐conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. The bound secondary antibody was visualized with Immobilon Western (Sigma‐Aldrich) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Signal intensities of bands were quantified with the Gel analysis program of the ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Statistics

All data are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical significance was evaluated using the unpaired Student's t test. For multiple comparisons of data, ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test was used unless otherwise indicated. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS version 23 software (SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

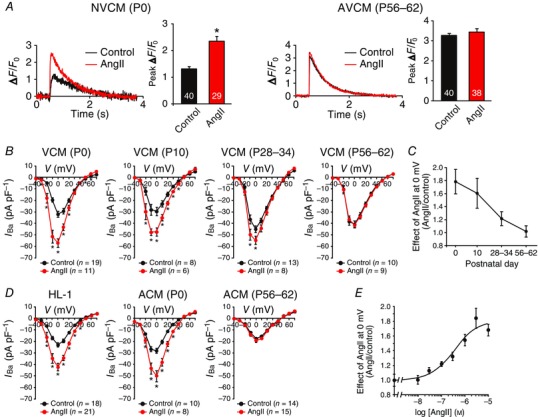

AngII increases twitch Ca2+ transients in neonatal but not adult ventricular cardiomyocytes

It is of debate whether AngII augments cardiac contractility (Allen et al. 1988; Ikenouchi et al. 1994; Petroff et al. 2000; Aiello & Cingolani, 2001; Bkaily et al. 2005; Gassanov et al. 2006). We hypothesized that this is partly because AngII differentially regulates cardiac contractility at distinct developmental stages. Thus, we first compared the effects of AngII on twitch Ca2+ transients in mouse neonatal and adult ventricular cardiomyocytes (NVCMs and AVCMs, respectively). In NVCMs, 2 h treatment of AngII (3 μm) significantly increased the peak of Ca2+ transients (Fig. 1 A). However, AngII had no significant effect on Ca2+ transients in AVCMs (Fig. 1 A). These results suggested that AngII may exert a positive inotropic effect in immature cardiomyocytes.

Figure 1. AngII increases twitch Ca2+ transients and L‐type Ca2+ channel currents in immature cardiomyocytes.

A, effect of AngII on Ca2+ transients in Fluo‐4‐loaded NVCMs [postnatal day (P)0, left] and AVCMs (P56–62, right). Each left‐hand panel, representative Ca2+ transients of control cardiomyocytes (black lines) and cardiomyocytes treated with AngII (3 μm, 2 h) (red lines). Each right‐hand panel, the summary of peak ΔF/F 0. The number of observed cells is indicated in the graph (NVCMs from 15 mouse pups and AVCMs from 3 mice). * P < 0.01 versus each control. B, effect of AngII (3 μm, 2 h) on peak current density–voltage relationships of L‐type Ca2+ channels in VCMs (P0 from 12 mouse pups, P10 from 3 mice, P28–34 from 3 mice, and P56–62 from 3 mice). The number of observed cells is indicated in the graph. * P < 0.05 versus each control. C, age‐dependent effect of AngII on peak L‐type Ca2+ channel currents at 0 mV shown in B. D, effect of AngII (3 μm, 2 h) on peak current density–voltage relationship of L‐type Ca2+ channels in HL‐1 cardiomyocytes, neonatal (P0 from 15 mouse pups) and adult (P56–62 from 4 mice) atrial cardiomyocytes (ACMs). The number of observed cells is indicated in the graph. * P < 0.05 versus each control. E, concentration–response curve of AngII‐induced increase in peak L‐type Ca2+ channel currents at 0 mV in HL‐1 cardiomyocytes (n = 6–21 cells in each concentration). The curve was fit by the Hill equation.

Age‐dependent effect of AngII on cardiac L‐type Ca2+ channels

L‐type Ca2+ channel currents are crucial for the Ca2+‐induced Ca2+ release from the cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Thus, we next examined the effects of AngII on L‐type Ca2+ channel currents with Ba2+ as a charge carrier. Two hours of treatment of AngII (3 μm) almost doubled the amplitude of peak L‐type Ca2+ channel currents at 0 mV in immature cardiomyocytes such as NVCMs (P0) (Fig. 1 B), an atrial myocyte cell line, HL‐1 (Fig. 1 D), and mouse neonatal atrial cardiomyocytes (Fig. 1 D). This response to AngII, however, gradually decreased in an age‐dependent manner and was eventually abolished in adult ventricular and atrial cardiomyocytes (P56–62) (Fig. 1 B–D). AngII increased the amplitude of peak L‐type Ca2+ channel currents in HL‐1 cardiomyocytes in a concentration‐dependent manner with EC50 and Hill coefficient of 360 nm and 0.90, respectively (Fig. 1 E).

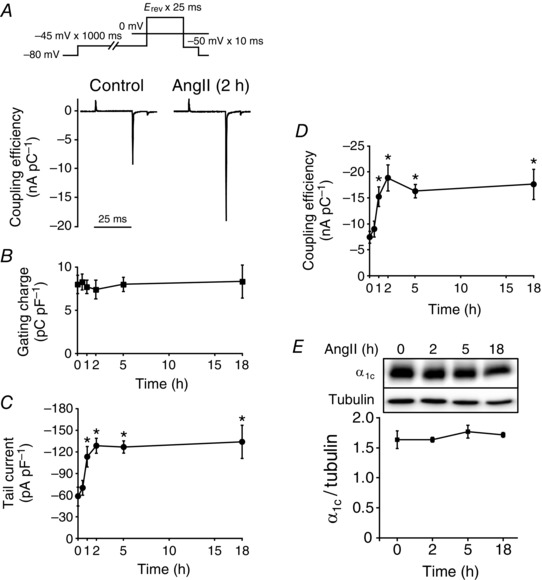

Mechanism employed by AngII to increase L‐type Ca2+ channel activity

To clarify the mechanisms by which AngII augments L‐type Ca2+ channel currents, we measured, in NVCMs, the gating charge upon depolarization to the reversal potential of L‐type Ca2+ channels (E rev) and the amplitude of peak tail currents after repolarization from E rev to –50 mV (Fig. 2 A). AngII did not increase gating charges but increased the amplitude of tail currents in a time‐dependent manner within 2 h (Fig. 2 B and C). As a result, AngII increased the ratio of the amplitude of tail currents to gating charges (Fig. 2 D), indicating that AngII increased the efficiency of the coupling between the voltage‐sensing domain and activation gate of L‐type Ca2+ channels. This response continued as long as 18 h. Consistent with this, immunoblotting revealed that AngII did not change the expression level of CaV1.2α1c subunits for 18 h in HL‐1 cardiomyocytes (Fig. 2 E). These results indicated that AngII activates L‐type Ca2+ channels by increasing the availability and/or open probability but not the number of single L‐type Ca2+ channels.

Figure 2. Mechanism underlying the activation of L‐type Ca2+ channels by AngII in NVCMs.

A, representative traces of gating charges and Ba2+ tail currents of L‐type Ca2+ channels in NVCMs (P0 or P1) in the presence or absence of AngII (3 μm, 2 h). Ordinate indicates the coupling efficiency (nA pC–1). Inset, voltage protocol. B–D, time‐dependent effect of AngII (3 μm) on gating charge density (B), peak Ba2+ tail current density (C) and the coupling efficiency (D) of L‐type Ca2+ channels in NVCMs (P0 or P1); n = 6–9 cells from 10–15 mouse pups in each time point. * P < 0.05 versus each control (0 h). E, AngII did not alter the expression level of CaV1.2α1c subunits in HL‐1 cardiomyocytes. HL‐1 cardiomyocytes were treated with AngII (3 μm) for the indicated duration. Whole‐cell lysates (α1c, 50 μg per lane; tubulin, 10 μg per lane) from these HL‐1 cardiomyocytes were immunoblotted with antibodies against CaV1.2α1c and tubulin. Tubulin was used as an internal control; n = 4 independent blots. * P < 0.05 versus control (0 h). In each panel contrast and brightness were adjusted to the whole image to make the features of interest clearer.

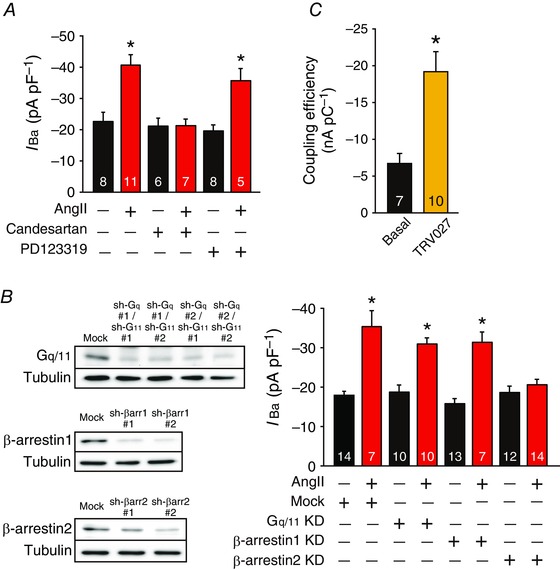

AngII activates L‐type Ca2+ channels through AT1 receptors and β‐arrestin2

We henceforth analysed the signal transduction system mediating the effect of AngII on L‐type Ca2+ channels in immature cardiomyocytes. We found that a selective AT1 receptor antagonist, candesartan (10 μm, AdooQ BioScience, Irvine, CA, USA), but not a selective AT2 receptor antagonist, PD123319 (3 μm, Wako), completely abolished the AngII‐induced increase in peak L‐type Ca2+ channel current densities in HL‐1 cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3 A), indicating the involvement of AT1 receptors in this response. Furthermore, knockdown of β‐arrestin2 but not Gq/11 or β‐arrestin1 significantly suppressed the effect of AngII (Fig. 3 B). Consistent with this, a β‐arrestin‐biased AT1 receptor agonist, TRV027 (customarily produced by Peptide Institute, Inc., Osaka, Japan), activated L‐type Ca2+ channels as efficaciously as AngII in NVCMs (Fig. 3 C). These results indicated that AngII activates L‐type Ca2+ channels through AT1 receptors and β‐arrestin2 in immature cardiomyocytes.

Figure 3. AngII activates L‐type Ca2+ channels through AT1 receptors and β‐arrestin2 in immature cardiomyocytes.

A, effect of candesartan (10 μm) or PD123319 (3 μm) on peak L‐type Ca2+ channel current density at 0 mV in HL‐1 cardiomyocytes in the presence or absence of AngII (3 μm, 2 h). HL‐1 cardiomyocytes were pretreated with antagonists for 30 min before treatment of AngII. The number of observed cells is indicated in the graph. * P < 0.05 versus control. B, left‐hand panel, representatives of three independent immunoblots of shRNA‐mediated knockdown (KD) of Gq/11, β‐arrestin1 and β‐arrestin2 in HL‐1 cardiomyocytes. Whole‐cell lysates (10–20 μg per lane) from these HL‐1 cardiomyocytes were immunoblotted with indicated antibodies. In each panel contrast and brightness were adjusted to the whole image to make the features of interest clearer. Right‐hand panel, effect of shRNA (sh)‐Gq#1/11#1, sh‐β‐arrestin1#2 or sh‐β‐arrestin2#2 on peak L‐type Ca2+ channel current density at 0 mV in HL‐1 cardiomyocytes in the presence or absence of AngII (3 μm, 2 h). The number of observed cells is indicated in the graph. * P < 0.01 versus basal of mock. C, effect of TRV027 (3 μm, 2 h) on the coupling efficiency of L‐type Ca2+ channels in NVCMs. * P < 0.01 versus basal. The number of observed cells is indicated in the graph (NVCMs from 14 mouse pups).

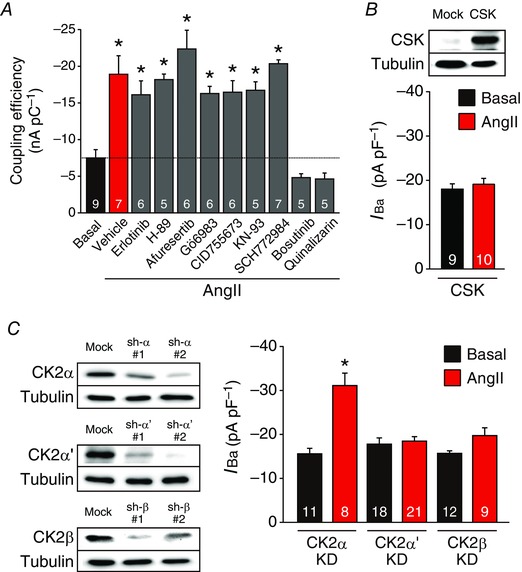

SFKs and CK2α’β are required for the effect of AngII on L‐type Ca2+ channels

The results described in Fig. 2 indicated that AngII post‐translationally modifies L‐type Ca2+ channels in immature cardiomyocytes. Thus, to elucidate possible involvement of protein kinases in the AngII‐induced response (Hunyady & Catt, 2006; Karnik et al. 2015), we examined, in NVCMs, the effects of an array of pharmacological inhibitors of kinases that are known to be activated by AngII and/or to regulate L‐type Ca2+ channels (Fig. 4 A). The effect of AngII was not affected by pretreatment of an epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor, erlotinib (0.1 μm, Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI, USA); a protein kinase A (PKA) inhibitor, H‐89 (1 μm, Sigma‐Aldrich); a protein kinase B inhibitor, afuresertib (1 μm, ChemScene, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA); a protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitor, Gö6983 (0.5 μm, Wako); a protein kinase D inhibitor, CID755673 (3 μm, Sigma‐Aldrich); a calcium/calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase II inhibitor, KN‐93 (1 μm, Sigma‐Aldrich); or an extracellular signal‐regulated kinase inhibitor, SCH772984 (1 μm, AdooQ). However, pretreatment of an Src‐family tyrosine kinase (SFK) and Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor, bosutinib (2 μm, Sigma‐Aldrich), or a CK2 inhibitor, quinalizarin (3 μm, Sigma‐Aldrich), completely inhibited the effect of AngII.

Figure 4. Requirement for SFKs and CK2α’β for the AngII‐mediated activation of L‐type Ca2+ channels in immature cardiomyocytes.

A, effects of pharmacological inhibitors on AngII‐mediated activation of L‐type Ca2+ channels in NVCMs. Ordinate indicates the coupling efficiency (nA pC–1) of L‐type Ca2+ channels. NVCMs were treated with vehicle, erlotinib (0.1 μm), H‐89 (1 μm), afuresertib (1 μm), Gö6983 (0.5 μm), CID755673 (3 μm), KN‐93 (1 μm), SCH772984 (1 μm), bosutinib (2 μm) or quinalizarin (3 μm) for 30 min before treatment of AngII (3 μm, 2 h). Dashed black line indicates the mean value in the basal condition. Twenty‐eight mouse pups were used. * P < 0.05 versus basal. B, upper panel, a representative immunoblot of three independent experiments overexpressing CSK in HL‐1 cardiomyocytes. Lower panel, peak L‐type Ca2+ channel current density at 0 mV in HL‐1 cardiomyocytes overexpressing CSK in the presence or absence of AngII (3 μm, 2 h). C, left‐hand panel, representatives of three independent experiments of shRNA‐mediated knockdown (KD) of CK2α, CK2α’ and CK2β in HL‐1 cardiomyocytes. Right‐hand panel, effect of sh‐CK2α#2, sh‐CK2α’#2 or sh‐CK2β#1 on peak L‐type Ca2+ channel current density at 0 mV in HL‐1 cardiomyocytes in the presence or absence of AngII (3 μm, 2 h). * P < 0.05 versus each basal. The number of observed cells is indicated in the graph (A–C). Whole‐cell lysates (10 μg per lane) from HL‐1 cardiomyocytes were immunoblotted with indicated antibodies (B and C). In each panel contrast and brightness were adjusted to the whole image to make the features of interest clearer.

We also found that overexpression of CSK, an endogenous inhibitor of SFKs (Okada, 2012), inhibited AngII‐induced activation of L‐type Ca2+ channels in HL‐1 cardiomyocytes (Fig. 4 B).

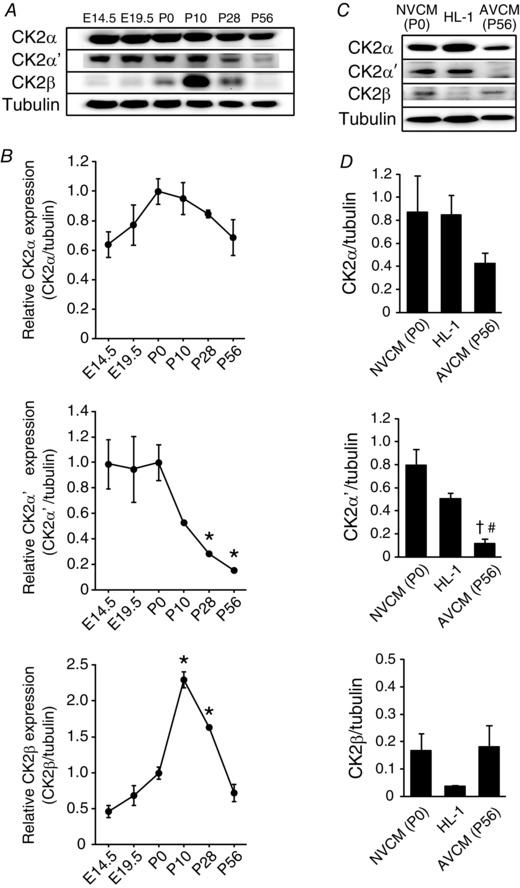

CK2 is a heterotetramer consisting of two catalytic subunits (α and/or α’) and two regulatory β subunits (Litchfield, 2003). Knockdown of CK2α’ or CK2β, but not CK2α, significantly suppressed the effect of AngII on L‐type Ca2+ channels in HL‐1 cardiomyocytes (Fig. 4 C), indicating a requirement of CK2α’β in this response. Immunoblotting revealed that the expression level of CK2α’ gradually decreased during maturation of the heart (Fig. 5 A and B), and it was 7 and 4.5 times higher in NVCMs (P0) and HL‐1 cardiomyocytes than in AVCMs (P56), respectively (Fig. 5 C and D).

Figure 5. Expression levels of CK2α, α’ and β during the development of mouse ventricular cardiomyocytes.

A and B, mouse VCMs [embryonic days (E) 14.5 from 3 pregnant mice, E19.5 from 3 pregnant mice, P0 from 5 pups in each sample, P10 from 3 mice, P28 from 3 mice and P56 from 3 mice] were extracted. These whole‐cell lysates (10 μg per lane) were immunoblotted with indicated antibodies. Data were normalized to each P0 group; n = 3 independent blots. * P < 0.05 versus each P0 group. C and D, expression levels of CK2α, α’ and β in NVCMs (P0) and HL‐1 cardiomyocytes and AVCMs (P56). Whole‐cell lysates (10 μg per lane) were immunoblotted with indicated antibodies. Data were normalized to tubulin; n = 3 independent blots. † P < 0.05 versus each NVCM (P0) group, # P < 0.05 versus HL‐1 cardiomyocytes group. Representative immunoblot (A and C) and summary of the data (B and D) are shown. In each panel contrast and brightness were adjusted to the whole image to make the features of interest clearer. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test (B) and Bonferroni correction (D).

AngII sequentially activates SFKs and CK2α’β

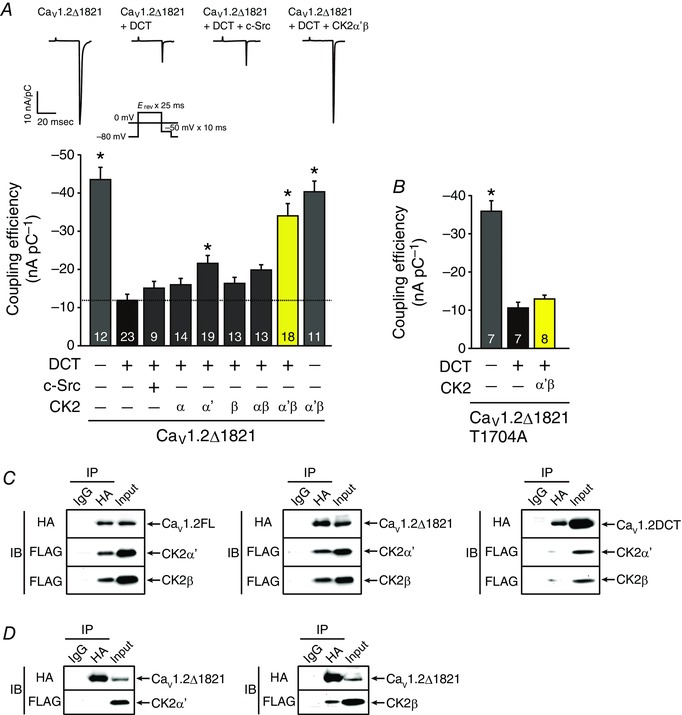

The C‐terminus of cardiac CaV1.2α1c subunit is proteolytically processed in vivo (De Jongh et al. 1996), and the cleaved distal C‐terminus non‐covalently rebinds through the distal C‐terminus regulatory domain (DCRD) to their proximal C‐terminal regulatory domain (PCRD), thereby autoinhibiting CaV1.2 channel activity (Fig. 6 A) (Gao et al. 2001; Hulme et al. 2006). To determine the order in which SFKs and CK2 mediate the effect of AngII to CaV1.2 channels, we examined whether these kinases could directly reverse the autoinhibition of recombinant CaV1.2 channels. We cotransfected cDNA encoding c‐Src or CK2 subunits with those encoding CaV1.2Δ1821, DCT, β2C and α2δ1 subunits in tsA201 cells. No increase in the coupling efficiency for CaV1.2Δ1821 + DCT channels was observed with coexpression of c‐Src (Fig. 6 A). Overexpression of CK2α’, but not CK2α, CK2β or CK2αβ, slightly but significantly increased the coupling efficiency of CaV1.2Δ1821 + DCT channels (Fig. 6 A). Overexpression of CK2α’β significantly increased the coupling efficiency of CaV1.2Δ1821 + DCT channels to a level similar to that of CaV1.2Δ1821 channels (Fig. 6 A). Moreover, it did not further increase the coupling efficiency of CaV1.2Δ1821 channels. Threonine 1704 (Thr1704) in the PCRD was reported to be the substrate of CK2 (Fuller et al. 2010). Indeed, CK2α’β failed to activate CaV1.2 channels composed of CaV1.2Δ1821T1704A, DCT, β2C and α2δ1 subunits (Fig. 6 B), further suggesting that CK2α’β directly activates CaV1.2 channels.

Figure 6. Activation of autoinhibited CaV1.2Δ1821 + DCT channels by CK2α’β but not c‐Src.

A, coupling efficiency for CaV1.2Δ1821 and CaV1.2Δ1821 + DCT channels in tsA201 cells overexpressing Myc‐c‐Src, CK2α, CK2α’, CK2β, CK2αβ and CK2α’β as indicated. Inset, representative traces of gating currents and Ba2+ tail currents of recombinant CaV1.2 channels and voltage protocol. * P < 0.01 versus CaV1.2Δ1821 + DCT channels. B, requirement of Thr1704 phosphorylation in CaV1.2 channels for CK2α’β‐mediated activation of CaV1.2Δ1821 + DCT channels. Coupling efficiency for CaV1.2Δ1821T1704A and CaV1.2Δ1821T1704A + DCT channels in tsA201 cells with or without overexpression of CK2α’β. * P < 0.01 versus CaV1.2Δ1821T1704A + DCT channels. The number of observed cells is indicated in the graph (A and B). C and D, CK2α’β bound to CaV1.2Δ1821 through CK2β subunits. HA‐CaV1.2 channels, FLAG‐CK2α’ and FLAG‐CK2β were expressed in tsA201 cells as indicated. Antibody‐tagged protein complexes were co‐immunoprecipitated (IP) with non‐immune IgG or antibody against HA from lysates and analysed by immunoblotting (IB) with antibodies against HA and FLAG as indicated. Data are representative from three independent experiments. C, co‐immunoprecipitation of HA‐CaV1.2 (FL, Δ1821 or DCT) channels with FLAG‐CK2α’ + FLAG‐CK2β. D, HA‐CaV1.2Δ1821 channels and either FLAG‐CK2α’ (left) or FLAG‐CK2β (right) were expressed in tsA201 cells. Co‐immunoprecipitation of HA‐CaV1.2Δ1821 channels with FLAG‐CK2α’ (left) or FLAG‐CK2β (right). In each panel contrast and brightness were adjusted to the whole image to make the features of interest clearer.

To test how CK2α’β interacts with CaV1.2 channels, we coexpressed cDNA encoding HA‐CaV1.2 [full‐length (FL), Δ1821, or DCT], β2C and α2δ1 subunits with FLAG‐CK2α’ and FLAG‐CK2β in tsA201 cells. FLAG‐CK2α’ and FLAG‐CK2β both co‐immunoprecipitated with HA‐FLCaV1.2 and HA‐CaV1.2Δ1821 channels but not HA‐DCT (Fig 6 C). Furthermore, when either FLAG‐CK2α’ or FLAG‐CK2β was individually coexpressed with HA‐CaV1.2Δ1821, FLAG‐CK2β but not FLAG‐CK2α’ co‐immunoprecipitated with HA‐CaV1.2Δ1821 channels (Fig. 6 D). Thus, it is likely that CK2α’β binds to CaV1.2 channels devoid of DCT through CK2β.

SFKs removes the inhibition of CK2α’β through p27

Although the effect of CK2α’β on CaV1.2 channels was tightly regulated by AngII in cardiomyocytes (Fig. 4), CK2α’β activated CaV1.2 channels constitutively in tsA201 cells (Fig. 6 A). Therefore, there may be a means of inhibiting CK2α’β in cardiomyocytes, and this inhibitor might be released by AngII. It was reported that a cyclin‐dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor, p27, inhibits CK2α’ in cardiomyocytes (Hauck et al. 2008). We found that knockdown of p27 indeed constitutively activated L‐type Ca2+ channels in HL‐1 cardiomyocytes (Fig. 7 A). This activity was almost completely inhibited by quinalizarin (3 μm) but not bosutinib (2 μm), consistent with direct activation of CaV1.2 channels by CK2α’β but not SFKs (Fig. 7 A). Knockdown of p27 occluded the effect of AngII on L‐type Ca2+ channel activity (Fig. 7 A). Furthermore, Myc‐p27 co‐immunoprecipitated with both FLAG‐CK2α’ and FLAG‐CK2β in tsA201 cells (Fig. 7 B). When HA‐CaV1.2Δ1821 was coexpressed with Myc‐p27, FLAG‐CK2α’ and FLAG‐CK2β, HA‐CaV1.2Δ1821 channels co‐immunoprecipitated with not only FLAG‐CK2α’β but also Myc‐p27 (Fig. 7 C). Thus, it is likely that CaV1.2 channels, CK2α’β and p27 form a macromolecular complex. AngII did not alter the expression level of p27 for 2 h in HL‐1 cardiomyocytes (Fig. 7 D).

We hypothesized that it is SFKs that remove the inhibitory effect of p27 on CK2α’β. A major phosphorylation site of p27 by SFKs is tyrosine 88 (Tyr88), which plays an important role in regulating inhibition of CDK by p27 (Jakel et al. 2012). AngII significantly increased Tyr88 phosphorylation of p27 in HL‐1 cardiomyocytes in a time‐dependent manner between 5 and 120 min (Fig. 7 E). Pretreatment of bosutinib (2 μm) almost completely inhibited Tyr88 phosphorylation of p27 by AngII in HL‐1 cardiomyocytes (Fig. 7 F). In tsA201 cells, CK2α’β‐mediated increase in the activity of CaV1.2 channels was completely inhibited by coexpression of wild‐type (WT) p27 or a phosphorylation‐resistant mutant of p27Y88F (Fig. 7 G). In contrast, a phosphomimetic mutant p27Y88E was unable to inhibit CK2α’β (Fig. 7 G). Furthermore, coexpression of c‐Src fully reversed the inhibitory effect of WT p27 but not p27Y88F on CK2α’β (Fig. 7 G). As assessed with immunoprecipitation, p27Y88E could bind to CK2α’β as efficiently as WT p27 in the presence (Fig. 7 H) or absence of CaV1.2Δ1821 channels (Fig. 7 I). These results suggested that AngII does not physically dissociate p27 from CK2α’β but impairs the ability of p27 to inhibit CK2α’β through Tyr88 phosphorylation by SFKs, thus leading to activation of CaV1.2 channels.

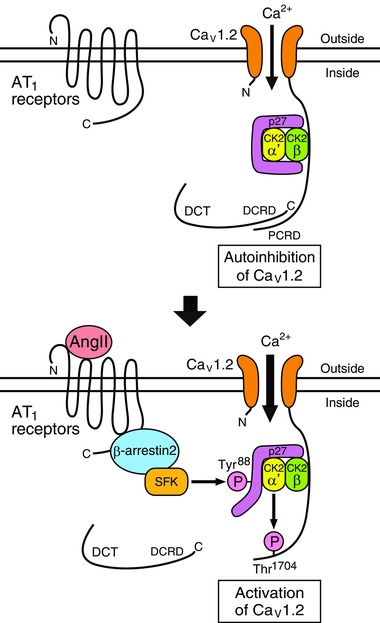

Discussion

We found that AngII augmented twitch Ca2+ transients by activating L‐type Ca2+ channels in immature but not mature cardiomyocytes (Fig. 8). AngII caused this effect through AT1 receptors and β‐arrestin2. β‐Arrestin2 activated SFKs, which removed the inhibitory effect of p27 on CK2α’β. Then, CK2α’β phosphorylated Thr1704 in the PCRD of CaV1.2α1c subunits and reversed the autoinhibition of CaV1.2 channels by the DCT (Gao et al. 2001; Hulme et al. 2006), thereby activating CaV1.2 channels. It was likely that CaV1.2 channels, CK2α’β and p27 formed a macromolecular complex. These results suggest that AngII may exert a positive inotropic effect through this novel signalling pathway in immature cardiomyocytes although we cannot exclude the possibility that other changes in Ca2+ signalling may also contribute to an increase in Ca2+ transients in response to AngII.

Figure 8. A signaling pathway revealed by this study.

Schematic illustration of the AngII‐mediated activation of CaV1.2 channels in immature cardiomyocytes.

It has been of debate whether AngII causes a positive inotropic effect on the heart (Lefroy et al. 1996; Watanabe & Endoh, 1998; Petroff et al. 2000; Palomeque et al. 2006; Rajagopal et al. 2006; Liang et al. 2010; Acharya et al. 2011) and/or activates L‐type Ca2+ channels (Allen et al. 1988; Ikenouchi et al. 1994; Petroff et al. 2000; Aiello & Cingolani, 2001; Bkaily et al. 2005; Gassanov et al. 2006). This controversy might have arisen at least in part because of the different ages of animals used in experiments. We found that the expression level of CK2α’ subunits age‐dependently decreased in the postnatal period (Fig. 5). The expression level of p27 in cardiomyocytes also increases with age (Torella et al. 2004). These facts may explain the age‐dependent inotropic effect of AngII. In a study using sheep perinatal fetuses (Acharya et al. 2011), administration of AngII significantly increased +dP/dt max of the left ventricle by ∼66%, consistent with our present observation. Lefkowitz and his colleagues reported that AT1 receptors have a positive inotropic effect in adult mouse cardiomyocytes through cooperative action of Gq/11/PKC and β‐arrestin2 (Rajagopal et al. 2006). Thus, the molecular mechanisms underlying inotropic effects of AngII on mature cardiomyocytes may be different from that on immature cardiomyocytes.

AngII increased L‐type Ca2+ channel activity in a concentration‐dependent manner with an EC50 of 360 nm, an ∼100 times higher value than that for AngII‐induced contraction of mouse abdominal aorta (4.6 nm) (Zhou et al. 2003). However, when rat NVCMs in culture were incubated with prorenin and angiotensinogen, cell proliferation equivalent to that induced by 100 nm AngII was observed, although the concentration of AngII in the medium remained < 1 nm (Saris et al. 2002). Thus, the local RAS exposes cardiomyocytes to higher concentrations of AngII than those in the plasma. Therefore, the signalling system identified in this study may be driven by the local RAS in the heart.

The effect of AngII on L‐type Ca2+ channels was attenuated by inhibition of SFKs or CK2 (Fig. 4). Both SFKs and CK2 are included in the interactome of β‐arrestins (Xiao et al. 2007). However, we considered that SFKs work upstream to CK2α’β in this signalling system from the following three pieces of evidence. First, in tsA201 cells, overexpression of CK2α’β but not c‐Src significantly activated recombinant CaV1.2 channels (Fig. 6 A). Second, the effect of AngII was almost completely inhibited by the alanine substitution of Thr1704, a substrate of CK2 (Fuller et al. 2010) (Fig. 6 B). Finally, in HL‐1 cardiomyocytes, enhancement of L‐type Ca2+ channel activity by knockdown of p27 was inhibited by quinalizarin but not bosutinib (Fig. 7 A). However, because SFKs are also reported to directly phosphorylate and augment L‐type Ca2+ channel activity in native cells such as neurons, smooth muscle cells and cardiomyocytes (Hu et al. 1998; Bence‐Hanulec et al. 2000; Dubuis et al. 2006; Gui et al. 2006), AngII might upregulate L‐type Ca2+ channels not only through CK2α’β but also through SFKs.

Hauck et al. (2008) reported that AngII activated CK2α’ and thereby phosphorylated Ser83 and Thr187 of p27 in rat neonatal cardiomyocytes. These phosphorylations then impaired the ability of p27 to inhibit CK2α’. This is collectively suggestive of the existence of a positive feedback loop between p27 and CK2α’ that is regulated by CK2α’ itself. However, they did not identify what activated CK2α’ first. We propose that it is SFKs that first phosphorylate Tyr88 of p27 and impair its ability to inhibit CK2α’. This would then be followed by positive feedback between p27 and CK2α’. Indeed, SFKs significantly phosphorylated Tyr88 of p27 as early as 5 min after stimulation with AngII (Fig. 7 E). In addition, the phosphorylation‐resistant p27 mutant (Y88F) inhibited the effect of constitutively active CK2α’ on CaV1.2 channels, both in the presence and in the absence of c‐Src (Fig. 7 G). It was likely that physical dissociation of p27 from CK2α’ is not necessary for the disinhibition of CK2α’ (Fig. 7 H and I). Hauck et al. (2008) found that p27 knock‐out mice had significantly higher contractility of the left ventricle, especially in adulthood. We speculated that this was because CK2α’ activated CaV1.2 channels more strongly in the knock‐out compared with WT mice in adulthood when p27 expression level was high.

In the heart, the C‐terminus of most CaV1.2α1c subunits is truncated (Gao et al. 1997) and reassociated with the PCRD, and autoinhibits CaV1.2 channels (Gao et al. 2001; Hulme et al. 2006). PKA is bound to CaV1.2α1c subunits through A‐kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs) associated with the distal C‐terminus of the CaV1.2α1c subunit (Marshall et al. 2011). It phosphorylates Ser1700 in the PCRD, and thereby attenuates the autoinhibitory effect of the distal C‐terminus and activates CaV1.2 channels (Fuller et al. 2010). We found that CK2α’ was bound to CaV1.2α1c subunits devoid of DCT through CK2β (Fig. 6 C and D), phosphorylated Thr1704 (Fig. 6 B), and thereby activated CaV1.2 channels (Fig. 6 A). Thus, it can be posited that what CK2β is for CK2α’ is analogous to what AKAPs are for PKA. Because both Ser1700 and Thr1704 are located in close proximity at the interface between the DCRD and the PCRD (Fuller et al. 2010), CK2α’ may activate CaV1.2 channels in a manner similar to PKA. Indeed, CK2α’β like PKA increased the coupling efficiency between the voltage‐sensing domain and the activation gate of CaV1.2 channels (Fig. 2) (Fuller et al. 2010).

β‐Adrenergic stimulation increases cardiac L‐type Ca2+ channel currents by ∼100 to 200% within several minutes (McDonald et al. 1994). This response is transient and desensitized quickly. AngII was as efficacious as catecholamines in activating L‐type Ca2+ channel currents (Fig. 1), but its effect was slower and more sustaining (Fig. 2). This may be because catecholamines activate PKA through G proteins whereas AngII activates CK2α’ through β‐arrestin2 (Ahn et al. 2004; Shenoy et al. 2006). In the perinatal period of mammals, catecholamines secreted from the adrenal medulla and circulating and local AngII play a crucial role in pups’ response to circulatory stresses (Heymann et al. 1981). These two systems may be complementary in regulating cardiac function in this period by means of their different time course of actions. The action of AngII on cardiac L‐type Ca2+ channels continues as long as > 18 h and seems to be important for subacute maintenance of the circulatory system in the perinatal period. However, we do not know the exact molecular mechanisms underlying the slow response of L‐type Ca2+ channels to AngII. Because SFKs submaximally phosphorylated p27 at 5 min after AT1 receptor stimulation (Fig. 7 E), the rate‐limiting step in this signalling pathway may exist at the step of disinhibition of CK2 or phosphorylation of CaV1.2 by CK2. In this context, it is of note that CK2 usually requires negative charges near its target serine/threonine for effective phosphorylation (Litchfield, 2003). Thus, a negative charge added by coincident phosphorylation of Ser1700 by PKA could enable CK2α’β to phosphorylate Thr1704 more promptly.

We found that a β‐arrestin‐biased AT1 receptor agonist TRV027 was as effective as AngII in activating L‐type Ca2+ channels (Fig. 3 C). This agent activates β‐arrestins but inhibits Gq/11 proteins coupled to AT1 receptors and thus has an ideal profile for therapeutics against heart failure (Violin et al. 2010). However, this drug failed to meet either the primary or the secondary endpoints in the phase 2b BLAST‐AHF trial that enrolled adult patients (Felker et al. 2015; Greenberg, 2016). In this regard, TRV027 decreased mean atrial pressure and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure but only modestly increased cardiac output in a tachypacing‐induced heart failure model of adult canines (Boerrigter et al. 2012). We speculate that this was because of the age‐dependent effect of AT1 receptors on cardiac L‐type Ca2+ channels. Thus, if we can extrapolate the present observation to humans, we consider that TRV027 might be more suitable for paediatric than for adult heart failure. In the field of children's health care, the little progress that has been made over the past decades for treating adult heart failure has been sufficiently translated into treatments regarding paediatric heart failure (Hsu & Pearson, 2009). Thus, β‐arrestin‐biased AT1 receptor agonists, which have not only a positive inotropic effect but an anti‐apoptotic effect on cardiomyocytes, may be used as valuable therapeutics for paediatric heart failure in the future (Kim et al. 2012).

Additional information

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

All studies were performed in the Department of Molecular Pharmacology at Shinshu University School of Medicine, Matusmoto, Japan. Conception and design of the work: T.K., T.N. and M.Y. Collection, assembly, analysis and interpretation of data: T.K., T.N., K.K., T.T. and M.Y. Drafting and revising the manuscript: T.K., T.N., K.K., T.T. and M.Y. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All persons designated as authors qualify for authorship, and all those who qualify for authorship are listed.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 24790210, 26860145, and 16K08546 to T.K.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr William A. Catterall for providing CaV1.2α1C subunit cDNA, Dr Hiroyuki Miyoshi for providing the lentiviral vector CSII‐EF‐MCS, Dr David W. Litchfield for providing antibodies against CK2α and CK2α’ subunits, Dr. William C. Claycomb for providing the HL‐1 cardiomyocytes and Ms Reiko Sakai for secretarial assistance.

Linked articles This article is highlighted by a Perspective by Horne & Hell. To read this Perspective, visit https://doi.org/10.1113/JP274260.

References

- Acharya G, Huhta JC, Haapsamo M, How OJ, Erkinaro T & Rasanen J (2011). Effect of angiotensin II on the left ventricular function in a near‐term fetal sheep with metabolic acidemia. J Pregnancy 2011, 634240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn S, Shenoy SK, Wei H & Lefkowitz RJ (2004). Differential kinetic and spatial patterns of β‐arrestin and G protein‐mediated ERK activation by the angiotensin II receptor. J Biol Chem 279, 35518–35525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiello EA & Cingolani HE (2001). Angiotensin II stimulates cardiac L‐type Ca2+ current by a Ca2+‐ and protein kinase C‐dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280, H1528–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen IS, Cohen NM, Dhallan RS, Gaa ST, Lederer WJ & Rogers TB (1988). Angiotensin II increases spontaneous contractile frequency and stimulates calcium current in cultured neonatal rat heart myocytes: insights into the underlying biochemical mechanisms. Circ Res 62, 524–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader M 2010). Tissue renin–angiotensin–aldosterone systems: targets for pharmacological therapy. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 50, 439–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bence‐Hanulec KK, Marshall J & Blair LA (2000). Potentiation of neuronal L calcium channels by IGF‐1 requires phosphorylation of the alpha1 subunit on a specific tyrosine residue. Neuron 27, 121–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bkaily G, Sculptoreanu A, Wang S, Nader M, Hazzouri KM, Jacques D, Regoli D, D'Orleans‐Juste P & Avedanian L (2005). Angiotensin II‐induced increase of T‐type Ca2+ current and decrease of L‐type Ca2+ current in heart cells. Peptides 26, 1410–1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerrigter G, Soergel DG, Violin JD, Lark MW & Burnett JC, Jr (2012). TRV120027, a novel β‐arrestin biased ligand at the angiotensin II type I receptor, unloads the heart and maintains renal function when added to furosemide in experimental heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 5, 627–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton Pipkin F, Lumbers ER & Mott JC (1974). Factors influencing plasma renin and angiotensin II in the conscious pregnant ewe and its foetus. J Physiol 243, 619–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claycomb WC, Lanson NA Jr, Stallworth BS, Egeland DB, Delcarpio JB, Bahinski A & Izzo NJ Jr (1998). HL‐1 cells: a cardiac muscle cell line that contracts and retains phenotypic characteristics of the adult cardiomyocyte. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95, 2979–2984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jongh KS, Murphy BJ, Colvin AA, Hell JW, Takahashi M & Catterall WA (1996). Specific phosphorylation of a site in the full‐length form of the alpha 1 subunit of the cardiac L‐type calcium channel by adenosine 3‧,5‧‐cyclic monophosphate‐dependent protein kinase. Biochemistry 35, 10392–10402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubuis E, Rockliffe N, Hussain M, Boyett M, Wray D & Gawler D (2006). Evidence for multiple Src binding sites on the α1c L‐type Ca2+ channel and their roles in activity regulation. Cardiovasc Res 69, 391–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felker GM, Butler J, Collins SP, Cotter G, Davison BA, Ezekowitz JA, Filippatos G, Levy PD, Metra M, Ponikowski P, Soergel DG, Teerlink JR, Violin JD, Voors AA & Pang PS (2015). Heart failure therapeutics on the basis of a biased ligand of the angiotensin‐2 type 1 receptor. Rationale and design of the BLAST‐AHF study (Biased Ligand of the Angiotensin Receptor Study in Acute Heart Failure). JACC Heart Fail 3, 193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller MD, Emrick MA, Sadilek M, Scheuer T & Catterall WA (2010). Molecular mechanism of calcium channel regulation in the fight‐or‐flight response. Sci Signal 3, ra70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao T, Cuadra AE, Ma H, Bunemann M, Gerhardstein BL, Cheng T, Eick RT & Hosey MM (2001). C‐terminal fragments of the α1C (CaV1.2) subunit associate with and regulate L‐type calcium channels containing C‐terminal‐truncated α1C subunits. J Biol Chem 276, 21089–21097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao T, Puri TS, Gerhardstein BL, Chien AJ, Green RD & Hosey MM (1997). Identification and subcellular localization of the subunits of L‐type calcium channels and adenylyl cyclase in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem 272, 19401–19407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassanov N, Brandt MC, Michels G, Lindner M, Er F & Hoppe UC (2006). Angiotensin II‐induced changes of calcium sparks and ionic currents in human atrial myocytes: potential role for early remodeling in atrial fibrillation. Cell Calcium 39, 175–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg B (2016). Novel therapies for heart failure‐ where do they stand? Circ J 80, 1882–1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy D (2015). Principles and standards for reporting animal experiments in The Journal of Physiology and Experimental Physiology . J Physiol 593, 2547–2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gui P, Wu X, Ling S, Stotz SC, Winkfein RJ, Wilson E, Davis GE, Braun AP, Zamponi GW & Davis MJ (2006). Integrin receptor activation triggers converging regulation of Cav1.2 calcium channels by c‐Src and protein kinase A pathways. J Biol Chem 281, 14015–14025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JE (2003). Historical perspective of the renin–angiotensin system. Mol Biotechnol 24, 27–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauck L, Harms C, An J, Rohne J, Gertz K, Dietz R, Endres M & von Harsdorf R (2008). Protein kinase CK2 links extracellular growth factor signaling with the control of p27(Kip1) stability in the heart. Nat Med 14, 315–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heymann MA, Iwamoto HS & Rudolph AM (1981). Factors affecting changes in the neonatal systemic circulation. Annu Rev Physiol 43, 371–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper SB, Te Pas AB, Lang J, van Vonderen JJ, Roehr CC, Kluckow M, Gill AW, Wallace EM & Polglase GR (2015). Cardiovascular transition at birth: a physiological sequence. Pediatr Res 77, 608–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi‐Hirose M, Kashihara T, Nakada T, Kurebayashi N, Shimojo H, Shibazaki T, Sheng X, Yano S, Hirose M, Hongo M, Sakurai T, Moriizumi T, Ueda H & Yamada M (2011). Decrease in the density of t‐tubular L‐type Ca2+ channel currents in failing ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300, H978–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu DT & Pearson GD (2009). Heart failure in children: part II: diagnosis, treatment, and future directions. Circ Heart Fail 2, 490–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu XQ, Singh N, Mukhopadhyay D & Akbarali HI (1998). Modulation of voltage‐dependent Ca2+ channels in rabbit colonic smooth muscle cells by c‐Src and focal adhesion kinase. J Biol Chem 273, 5337–5342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulme JT, Yarov‐Yarovoy V, Lin TW, Scheuer T & Catterall WA (2006). Autoinhibitory control of the CaV1.2 channel by its proteolytically processed distal C‐terminal domain. J Physiol 576, 87–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunyady L & Catt KJ (2006). Pleiotropic AT1 receptor signaling pathways mediating physiological and pathogenic actions of angiotensin II. Mol Endocrinol 20, 953–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikenouchi H, Barry WH, Bridge JH, Weinberg EO, Apstein CS & Lorell BH (1994). Effects of angiotensin II on intracellular Ca2+ and pH in isolated beating rabbit hearts and myocytes loaded with the indicator indo‐1. J Physiol 480, 203–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakel H, Peschel I, Kunze C, Weinl C & Hengst L (2012). Regulation of p27 (Kip1) by mitogen‐induced tyrosine phosphorylation. Cell Cycle 11, 1910–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jong P, Yusuf S, Rousseau MF, Ahn SA & Bangdiwala SI (2003). Effect of enalapril on 12‐year survival and life expectancy in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction: a follow‐up study. Lancet 361, 1843–1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnik SS, Unal H, Kemp JR, Tirupula KC, Eguchi S, Vanderheyden PM & Thomas WG (2015). International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. XCIX. Angiotensin Receptors: Interpreters of Pathophysiological Angiotensinergic Stimuli [corrected]. Pharmacol Rev 67, 754–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Krege JH, Kluckman KD, Hagaman JR, Hodgin JB, Best CF, Jennette JC, Coffman TM, Maeda N & Smithies O (1995). Genetic control of blood pressure and the angiotensinogen locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92, 2735–2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KS, Abraham D, Williams B, Violin JD, Mao L & Rockman HA (2012). β‐Arrestin‐biased AT1R stimulation promotes cell survival during acute cardiac injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 303, H1001–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima K, Amano Y, Yoshino K, Tanaka N, Sugamura K & Takeshita T (2014). ESCRT‐0 protein hepatocyte growth factor‐regulated tyrosine kinase substrate (Hrs) is targeted to endosomes independently of signal‐transducing adaptor molecule (STAM) and the complex formation with STAM promotes its endosomal dissociation. J Biol Chem 289, 33296–33310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefroy DC, Crake T, Del Monte F, Vescovo G, Dalla Libera L, Harding S & Poole‐Wilson PA (1996). Angiotensin II and contraction of isolated myocytes from human, guinea pig, and infarcted rat hearts. Am J Physiol 270, H2060–2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang W, Oudit GY, Patel MM, Shah AM, Woodgett JR, Tsushima RG, Ward ME & Backx PH (2010). Role of phosphoinositide 3‐kinase α, protein kinase C, and L‐type Ca2+ channels in mediating the complex actions of angiotensin II on mouse cardiac contractility. Hypertension 56, 422–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litchfield DW (2003). Protein kinase CK2: structure, regulation and role in cellular decisions of life and death. Biochem J 369, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumbers ER & Reid GC (1977). Effects of vaginal delivery and caesarian section on plasma renin activity and angiotensin II levels in human umbilical cord blood. Biol Neonate 31, 127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall MR, Clark JP, Westenbroek R 3rd, Yu FH, Scheuer T & Catterall WA (2011). Functional roles of a C‐terminal signaling complex of CaV1 channels and A‐kinase anchoring protein 15 in brain neurons. J Biol Chem 286, 12627–12639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald TF, Pelzer S, Trautwein W & Pelzer DJ (1994). Regulation and modulation of calcium channels in cardiac, skeletal, and smooth muscle cells. Physiol Rev 74, 365–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakada T, Flucher BE, Kashihara T, Sheng X, Shibazaki T, Horiuchi‐Hirose M, Gomi S, Hirose M & Yamada M (2012). The proximal C‐terminus of α1C subunits is necessary for junctional membrane targeting of cardiac L‐type calcium channels. Biochem J 448, 221–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada M (2012). Regulation of the SRC family kinases by Csk. Int J Biol Sci 8, 1385–1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliverio MI, Kim HS, Ito M, Le T, Audoly L, Best CF, Hiller S, Kluckman K, Maeda N, Smithies O & Coffman TM (1998). Reduced growth, abnormal kidney structure, and type 2 (AT2) angiotensin receptor‐mediated blood pressure regulation in mice lacking both AT1A and AT1B receptors for angiotensin II. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95, 15496–15501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palomeque J, Sapia L, Hajjar RJ, Mattiazzi A & Vila Petroff M (2006). Angiotensin II‐induced negative inotropy in rat ventricular myocytes: role of reactive oxygen species and p38 MAPK. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290, H96–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul M, Poyan Mehr A & Kreutz R (2006). Physiology of local renin‐angiotensin systems. Physiol Rev 86, 747–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petroff MG, Aiello EA, Palomeque J, Salas MA & Mattiazzi A (2000). Subcellular mechanisms of the positive inotropic effect of angiotensin II in cat myocardium. J Physiol 529, 189–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Granger CB, Held P, McMurray JJ, Michelson EL, Olofsson B, Ostergren J, Yusuf S & Pocock S (2003). Effects of candesartan on mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure: the CHARM‐Overall programme. Lancet 362, 759–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal K, Whalen EJ, Violin JD, Stiber JA, Rosenberg PB, Premont RT, Coffman TM, Rockman HA & Lefkowitz RJ (2006). α‐Arrestin2‐mediated inotropic effects of the angiotensin II type 1A receptor in isolated cardiac myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103, 16284–16289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saris JJ, van den Eijnden MM, Lamers JM, Saxena PR, Schalekamp MA & Danser AH (2002). Prorenin‐induced myocyte proliferation: no role for intracellular angiotensin II. Hypertension 39, 573–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy SK, Drake MT, Nelson CD, Houtz DA, Xiao K, Madabushi S, Reiter E, Premont RT, Lichtarge O & Lefkowitz RJ (2006). α‐Arrestin‐dependent, G protein‐independent ERK1/2 activation by the β2 adrenergic receptor. J Biol Chem 281, 1261–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla AK, Xiao K & Lefkowitz RJ (2011). Emerging paradigms of β‐arrestin‐dependent seven transmembrane receptor signaling. Trends Biochem Sci 36, 457–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torella D, Rota M, Nurzynska D, Musso E, Monsen A, Shiraishi I, Zias E, Walsh K, Rosenzweig A, Sussman MA, Urbanek K, Nadal‐Ginard B, Kajstura J, Anversa P & Leri A (2004). Cardiac stem cell and myocyte aging, heart failure, and insulin‐like growth factor‐1 overexpression. Circ Res 94, 514–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga F, Sulyok E, Nemeth M, Tenyi I, Csaba IF & Gyori E (1981). Activity of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system in full‐term newborn infants during the first week of life. Acta Paediatr Acad Sci Hung 22, 123–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Violin JD, DeWire SM, Yamashita D, Rominger DH, Nguyen L, Schiller K, Whalen EJ, Gowen M & Lark MW (2010). Selectively engaging β‐arrestins at the angiotensin II type 1 receptor reduces blood pressure and increases cardiac performance. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 335, 572–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace KB, Hook JB & Bailie MD (1980). Postnatal development of the renin‐angiotensin system in rats. Am J Physiol 238, R432–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe A & Endoh M (1998). Relationship between the increase in Ca2+ transient and contractile force induced by angiotensin II in aequorin‐loaded rabbit ventricular myocardium. Cardiovasc Res 37, 524–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao K, McClatchy DB, Shukla AK, Zhao Y, Chen M, Shenoy SK, Yates JR 3rd & Lefkowitz RJ (2007). Functional specialization of beta‐arrestin interactions revealed by proteomic analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 12011–12016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Dirksen WP, Babu GJ & Periasamy M (2003). Differential vasoconstrictions induced by angiotensin II: role of AT1 and AT2 receptors in isolated C57BL/6J mouse blood vessels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285, H2797–2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]