Abstract

Background

Proper monitoring of labor and childbirth prevents many pregnancy-related complications. However, monitoring is still poor in many places partly due to the usability concerns of support tools such as the partograph. In 2011, the World Health Organization (WHO) called for the development and evaluation of context-adaptable electronic health solutions to health challenges. Computerized tools have penetrated many areas of health care, but their influence in supporting health staff with childbirth seems limited.

Objective

The objective of this scoping review was to determine the scope and trends of research on computerized labor monitoring tools that could be used by health care providers in childbirth management.

Methods

We used key terms to search the Web for eligible peer-reviewed and gray literature. Eligibility criteria were a computerized labor monitoring tool for maternity service providers and dated 2006 to mid-2016. Retrieved papers were screened to eliminate ineligible papers, and consensus was reached on the papers included in the final analysis.

Results

We started with about 380,000 papers, of which 14 papers qualified for the final analysis. Most tools were at the design and implementation stages of development. Three papers addressed post-implementation evaluations of two tools. No documentation on clinical outcome studies was retrieved. The parameters targeted with the tools varied, but they included fetal heart (10 of 11 tools), labor progress (8 of 11), and maternal status (7 of 11). Most tools were designed for use in personal computers in low-resource settings and could be customized for different user needs.

Conclusions

Research on computerized labor monitoring tools is inadequate. Compared with other labor parameters, there was preponderance to fetal heart monitoring and hardly any summative evaluation of the available tools. More research, including clinical outcomes evaluation of computerized childbirth monitoring tools, is needed.

Keywords: childbirth, obstetric labor, fetal monitoring, medical informatics applications, systematic review

Introduction

In 2015, an estimated 303,000 women died from pregnancy-related complications such as excessive bleeding, obstructed labor, and infections [1,2]. The obstructed labor complex directly contributes to 6-10% of the maternal deaths, in addition to contributing to other diseases for the mother and the baby [3,4].

Proper monitoring of the labor and delivery process with appropriate action based on findings is one of the keys to the prevention of pregnancy-related diseases and deaths [5,6]. Labor monitoring includes three main areas, namely fetal conditions, labor progress, and maternal conditions. The fetal parameters include fetal heart rate and amniotic fluid color, whereas labor progress is tracked through cervical dilation, uterine contractions, and fetal descent. The parturient’s condition is monitored by her blood pressure, temperature, urine, and mental state. The monitoring in many low-resource settings is hampered by the lack of user-friendly tools for labor management, limited access to evidence-based clinical guidelines for the providers of maternal health services, maternity provider factors, weak referral networks, and limited health financing [7].

Since 1994, the paper partograph has been promoted by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the standard labor monitoring tool [8], but to date its use is still poor in many low-resource settings due to many user and usability challenges [1,9-11]. To address these challenges, scientists in maternal health called for improvements of the partograph [1,12,13]. The WHO called for the development and evaluation of pragmatic electronic health (eHealth) solutions to health challenges [14].

Noteworthy, mobile health (mHealth) was embraced in many settings, especially chronic conditions with concomitant improvement in medical care [15,16]. It was hoped that next-generation system innovations could improve the quality of care during childbirth and reduce maternal deaths [17,18]. However, there seems to be a paucity of papers on computerized labor monitoring tools as is with mHealth in general.

We had a notion that the responses to various calls for better labor monitoring tools are still poor. Therefore, we set out to determine the volume and scope of research on computerized monitoring tools that can be used by health care providers in childbirth management.

Methods

We undertook a scoping review, as defined elsewhere [19,20], to assess the reactions to the WHO call for labor monitoring tools (computerized or otherwise) with the potential of being more acceptable to the stakeholders in maternity services. Tricco et al (2016) reiterate the purpose of scoping reviews as, “…to present a broad overview of the evidence pertaining to a topic, irrespective of study quality, and are useful when examining areas that are emerging, to clarify key concepts and identify gaps” [19]. In June and July 2016, we searched PubMed and Google Scholar databases for peer-reviewed and gray literature. The search was supplemented by manual searches in Google search engine and ResearchGate online repositories for other papers meeting the selection criteria.

The inclusion criteria were a paper written in English language, addressing an aspect of a computerized or mobile labor monitoring tool, for use by maternity service providers, and written between January 1, 2006 to May 31, 2016. We excluded literature on tools for use primarily by expectant parents and the numerous apps for nonprofessional use such as contraction monitoring at home or fetal growth monitoring.

Our key terms in the search included “labor,” “monitoring,” “computer,” “mobile,” “tool,” “provider,” “delivery,” and “birth.” We combined them in various ways to get search strings. An example of such a string is “With all ‘labor monitoring’ + plus at least one of ‘computer$ tool$ mobile provider$ delivery birth - consumer’ (anywhere in article).” At the title review stage, we combined the term “labor” with one or more of the other terms to get relevant papers.

Data collection started with the individual researcher or research assistant identifying and screening papers for allocated years. We then entered the search terms and filtered the results according to the desired years of publication. We sorted the results in ascending years to ease tracking of the viewed Web pages. Each collector exported the identified papers into Mendeley-1.16.1 reference manager (by Elsevier) and used it to remove duplicates.

The data collector imported the Mendeley (by Elsevier) output into Google Scholar or PubMed and applied more specific filters to the titles. The filters helped eliminate the nonhuman birth-related and non-computer tools. The subsequent titles were saved to an online library for further screening. Abstracts to the saved titles were downloaded and qualitatively analyzed to determine the target users. Uncertainty about the eligibility of an article was consensually resolved based on the selection criteria.

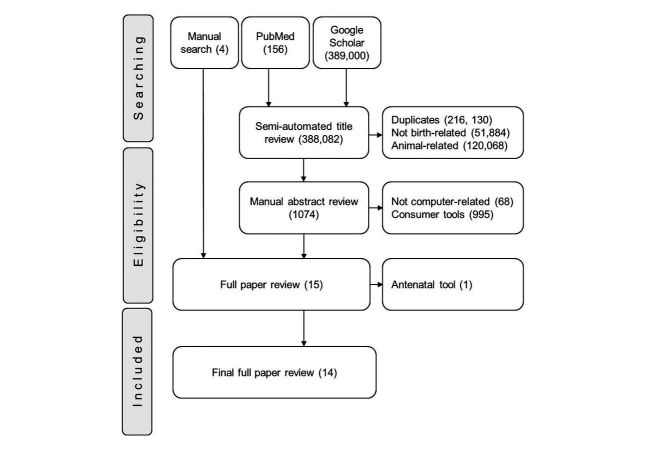

Full papers to abstracts with all eligibility criteria were retrieved. Manually identified abstracts or papers that were not part of the controlled search were added to the pool. All papers were scrutinized against all selection criteria. The remaining papers were included in the quantitative final analysis. These steps are summarized, as shown in Figure 1 , to mimic the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA). Each paper was read to decipher the focus, developmental stage, and computing platform of the labor monitoring tool.

Figure 1.

The steps of paper selection depicted in a PRISMA flow diagram. The number of articles included or excluded at each step is shown in brackets.

Results

Volume of Relevant Research

In the preliminary literature search, we retrieved 389,000 titles from Google Scholar and 156 from PubMed (Figure 1). These were imported into Mendeley 1.16.1 (by Elsevier) and duplicates removed. The titles were semiautomatically reviewed to remove papers about nonhuman or nonbirth related tools, which resulted in the exclusion of 388,082 entries. During the screening of abstracts for the remaining 1074 papers, we eliminated papers about tools that did not incorporate computers during labor monitoring use to leave 11 abstracts. Four abstracts identified in the manual literature search were added to the remaining 11 to get 15 abstracts used to identify papers for full review. At the full paper review stage, one paper (the Bacis program study by Horner in South Africa) was excluded because its subject tool was not designed for use during labor, which left 14 papers with all inclusion criteria for final analysis, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of papers included in the final analysis and the name of study tools.

| Paper (Reference number) | Yeara | Name of tool | |

| “Quality of prenatal and maternal care: Bridging the know-do gap” (QUALMAT study): an electronic clinical decision support system for rural sub-Saharan Africa [21] | 2013 | QUALMAT eCDSSb | |

| The Moyo fetal heart rate monitor [22] | 2014 | Moyo monitor | |

| mLabour: design and evaluation of a mobile partograph and labor ward management application [23] | 2016 | mLabour | |

| Continuous monitoring of cervical dilatation and fetal head station during labor [24] | 2007 | Computerized labor-monitor | |

| The design and implementation of the PartoPen maternal health monitoring system [25] | 2013 | PartoPen | |

| Improving maternal labor monitoring in Kenya using digital pen technology: a user evaluation [26] | 2012 | PartoPen | |

| Cost-effectiveness of a clinical decision support system in improving maternal health care in Ghana [27] | 2015 | QUALMAT eCDSS | |

| Impact of an electronic clinical decision support system on workflow in antenatal care: the QUALMAT eCDSS in rural health care facilities in Ghana and Tanzania [28] | 2015 | QUALMAT eCDSS | |

| A mobile multi-agent information system for ubiquitous fetal monitoring [29] | 2014 | Fetal IMAIS | |

| A study of an intelligent system to support decision making in the management of labour using the cardiotocograph–the infant study protocol [30] | 2016 | INFANT | |

| The development of a simplified, effective, labour monitoring-to-action (SELMA) tool for better outcomes in labour difficulty (BOLD): Study protocol [31] | 2015 | SELMA | |

| Life curve mobile application: an easier alternative to paper partograph [32] | 2015 | Life curve | |

| ePartogram: a mobile decision support tool to address labor complications [33] | 2013 | ePartogram | |

| Another set of eyes: Remote fetal monitoring surveillance aids the busy labor and delivery unit [34] | 2010 | ANGEL shield | |

aYear of publication.

beCDSS: electronic clinical decision support system.

Stage of Tool Development

As shown in Table 2, 4 out of 14 analyzed papers addressed labor monitoring tools still at the planning phase. We analyzed 7 papers about tools that had reached the implementation stage. The authors of the remaining 2 papers addressed the cost and impact on clinic workflow evaluation of one tool, QUALMAT eCDSS [21].

Table 2.

Stages of development for the computerized labor monitoring tools.

| Tool | Stage of developmenta | ||||

| Plan | Designing | Implementing | Formative evaluation | Summative evaluation | |

| QUALMAT eCDSSb | yc | y | y | y | z |

| Moyo monitor | y | y | zc | z | x |

| mLabour | y | y | z | y | x |

| Computerized labor-monitor | y | y | z | x | x |

| PartoPen | y | y | y | y | x |

| Fetal IMAIS | y | xc | x | x | x |

| INFANT | y | x | x | x | x |

| SELMA | y | x | x | x | x |

| Life curve | y | x | x | x | x |

| ePartogram | y | y | z | x | x |

| ANGEL shield | y | y | y | z | x |

aBased on the five stages of software development.

beCDSS: electronic clinical decision support system.

cx: stage not reached, y: completed stage, z: stage incomplete.

Five tools that were in the clinical trial or field testing [22-25] phase were classified under the implementation stage of development. Three tools had undergone formative assessment in form of user or cost evaluations [23,26,27]. We retrieved literature on a tool that was designed and tested in 2007, but we did not get publications on its advancement. One tool had a summative evaluation of its cost and impact on clinic workflow [28]. We did not get any tool with definitive summative evaluation, that is, pragmatic clinical outcomes (morbidity or mortality) studies.

Focus of Labor Monitoring Tool

The main parameters of focus in the analyzed papers were monitoring all labor parameters (7 papers) and fetal heart (3 papers). Four tools were designed to monitor one of three labor monitoring sections, whereas the rest could monitor multiple sections, as shown in Table 3. Authors addressing multiple labor monitoring sections were chiefly concerned with electronic versions of the partograph computing abilities. Therefore, their innovations potentially addressed the 15 parameters on a partograph. Those on fetal status focused on fetal heart monitoring with a cardiotocogram (CTG). The authors who addressed labor progress only specifically targeted cervical dilation and descent or station of a cephalic fetus.

Table 3.

Parameters on modified WHO partograph noted in the capability of computerized tools.

| Parameter on WHO partograph | Computerized tool to monitor parameter | ||||||||||

| 21a | 22b | 23c | 24d | 25e | 29f | 30g | 31h | 32i | 33j | 34k | |

| Fetal heart | yl | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | |

| Cervix opening | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | |||

| Descent of leading part | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | |||

| Amniotic fluid | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | ||||

| Molding of head | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | ||||

| Uterine contractions | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | |||

| Maternal pulse | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | ||||

| Maternal blood pressure | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | ||||

| Maternal temperature | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | ||||

| Urine protein | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | ||||

| Urine acetone | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | ||||

| Urine volume | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | ||||

| Time of membrane rupture | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | ||||

| Drug given | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | ||||

| Clinical diagnosis suggestion | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | |||

aQUALMAT eCDSS.

bMoyo monitor.

cmLabour.

dComputerized labor-monitor.

ePartoPen.

fFetal IMAIS.

gINFANT.

hSELMA.

iLife curve.

jePartogram.

kANGEL shield.

lParameter can be monitored with the tool.

All tools were intended for clinical diagnosis support based on algorithms. The least basic was the capability to take measurements or give alerts and reminders to maternity care providers [24,29,34]. However, 8 of 11 tools could also provide diagnosis and action suggestions to the user. The proposed SELMA tool could use machine learning models to predict diagnosis and outcomes for different contexts of use.

Computing Platforms for the Labor Monitoring Tools

As shown in Table 4 , the tools were mostly usable on existing personal computer hardware, especially mobile gadgets such as phones, laptops, and desktop computers. Majority communicated through client-server networks, and 4 of 11 (36%) used stand-alone computers. Microsoft Windows was the most commonly used operating system in desktops, and Android was used in most mobile systems. One tool (PartoPen) uses custom-made software, whereas the application-based tools were developed in a Java environment. For half of the tools, the authors did not specify the software framework used in development. Of 11 tools, only 4 were reported as customizable to suit a user’s context of work.

Table 4.

Computing platforms and adaptability for the labor monitoring tools.

| Tools | Computing Platform | Adaptable | |||

| Portability | Network environment | Operating systems | Software base | ||

| QUALMAT | Laptop and desktop | Stand-alone | MS Windows | Java | Yes |

| Moyo monitor | Mobile | Stand-alone | Customized | Undisclosed | No |

| mLabour | Mobile | Client-server | Android | Application | Yes |

| Computerized labor-monitor | Mobile and desktop | Stand-alone | Nonspecific | Ultrasound waves | Unknown |

| PartoPen | Mobile | Stand-alone | Livescribe pen | LiveCode “Penlet” | No |

| Fetal IMAIS | Mobile & desktop | Client-server, wireless | MS Windows | Java | Yes |

| INFANT | Mobile and desktop | Offline | MS Windows | Undisclosed | Unknown |

| SELMA | Mobile and desktop | Offline | Not applicable | Undisclosed | Unknown |

| Life curve | Mobile | Client-server | Android | Application | Yes |

| ePartogram | Mobile | Client-server | Android | Undisclosed | Unknown |

| ANGEL shield | Desktop | Client-server | MS Windows | Undisclosed | Yes |

The authors of the analyzed papers planned for adaptable tools. The intended context of tool use was stated as low-resource settings apart from the ANGEL shield. This computer program was made for and operated in a university hospital, but there were plans of rolling it out to nearby rural health centers. For 5 of 11 tools, it was reported that they could be customized to different contexts of use and even more functions added, where necessary.

Discussion

Principal Findings

In this review, out of over 380,000 papers, 14 qualified for the final analysis. They represented studies of 11 computerized tools capable of aiding health workers in maternity care. All labor parameters could be monitored by 7 of the 11 tools upon implementation. Only one tool had summative evaluations, which included cost and indicator studies. We did not find evidence of morbidity or mortality evaluation for any tool. Most tools used open source software that was also adaptable to common computers.

In this study, we chose to conduct a scoping review due to an ostensibly low volume of systematic evaluations and publications but with potentially more works on the subject. To this effect, many papers on pregnancy care applications were identified, although they were excluded from analysis for failure to meet other inclusion criteria. PubMed and Google Scholar formed the basis for the main search results due to their popularity among authors and a wide coverage of subjects. They were augmented with a manual search that indeed yielded more papers [22,23,32,33] included in the final analysis. The inclusion period of 2006 to 2016 was chosen to encompass the 5 years before and after the 2011 WHO call to evaluate all design and scale-up stages in eHealth [14], including e-labor monitoring tools.

Many papers were identified, which echo the findings of Kortteisto et al (2014), that is, mHealth is widespread [16]. However, similar to WHO and International Confederation of Midwives concerns in 2011 [13,14], only a handful addressed maternal labor and delivery monitoring. Moreover, as Hall et al found [17], the authors reported on tools that were in developmental stages, protocol preparation to field testing, without the definitive summative evaluation (pragmatic clinical outcomes studies) needed in health care research [35].

This state of affairs may be due to the human-intensive nature and high litigation potential of labor monitoring events that designing and testing a reliable computerized labor tool calls for more effort than is needed for an average medical condition. Another factor that could deter innovators is the difficulty in definitive summative evaluation of the tools in light of many confounders of labor outcomes. A similar situation in 2011 could have led the WHO to call for better research and evaluation of mHealth [14] such as labor monitoring tools. One should also be cognizant of the diverse labor monitoring contexts both within and without health facilities and communities, which were highlighted in the 2016 Lancet maternal health series [36,37]. However, the trend of research seems to be in a positive direction. From the works analyzed in this paper, the majority of the papers are authored after the WHO call to action, and all the documented evaluations were published after the call.

After the data collection for this review, another call to action on improving quality of maternity and newborn care was sounded through the Lancet maternal health series [37]. Furthermore, the potential of mHealth to help out is anticipated, with innovators urged not to be stifled by the fear of liability and litigation but to provide evidence-based tools for woman-centered care [18,38]. This series reinforced the findings of this review and stressed the need for further research for context-specific mobile childbirth monitoring tools.

Regarding the focus of the tools, it was obvious that the three main sections—fetal, labor progress, and maternal states—of labor monitoring received unequal attention. Monitoring the fetal condition, especially the fetal heart, was most researched, perhaps due to the discovery of cardiotocogram (CTG) that is efficacious in detecting fetal distress. CTG is sonoelectric and improving it through computerization was easier than inventing tools as was necessary for the labor progress. On the other hand, cervical dilation and maternal conditions are subjectively dependent on provider skills, and sociocultural or religious norms. Hence, the diversity of these conditions could hamper the design, testing, and development of widely acceptable tools to monitor labor progress and maternal conditions. With the recognition of the diversity of contexts of use but limited resources, it is prudent that generic tools are designed and developed or adapted for specific contexts [39].

The operating system platforms were generic in about half of the tools perhaps to cut development costs. This is also good for the diverse hardware that is increasingly portable. On the other hand, the programming software base was mostly undisclosed. This could be due to the early stages of development. Moreover, the authors were not yet committed to a specific program. However, the generic Java development environment was used in most specified cases. This would suggest that even the rest are more likely to use it in tool development.

Limitations

The sources of data for this review were not exhaustive of all literature (eg, papers not written in English), and as such, we could have omitted some papers on the computerized labor monitoring tools. This is a drawback, but the main sources are wide enough for an adequate sample and similar reviewers [17,20,40] increasingly adopt this approach. We also started the search with broad terms and narrowed them down as we saved different papers for subsequent analyses.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the scope and volume of research on computerized maternal labor monitoring tools is likely to be narrow and small. Fetal heart monitoring seems to dominate over other labor management parameters. Most tools are designed to use affordable computing platforms, but there is hardly any summative evaluation of the available tools. This may imply a slow response to the call for developing and evaluating computerized labor monitoring tools that could reduce labor-related disease. Further research, including clinical outcomes studies and publication of results, is needed on computerized tools for use in comprehensive childbirth monitoring.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Norwegian Agency for Development (NORAD) through the HITRAIN project and University of Bergen, UiB, for sponsoring this work. We thank the Association of Obstetricians & Gynecologists of Uganda secretariat for the support during the literature search and manuscript preparation. This work was supported by NORAD’s NORHED program through the HITRAIN project. However, the program had no role in determining the study design, data collection and analysis, or in the interpretation of results and writing of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CTG

cardiotocogram

- eCDSS

electronic clinical decision support system

- eHealth

electronic health

- mHealth

mobile health

- PRISMA

preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- WHO

World Health Organization

Footnotes

Authors' Contributions: All authors contributed to the review protocol. MB wrote the review protocol and participated in data collection and analysis. TT participated in data collection and analysis. All authors participated in manuscript preparation and approval of its final copy.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Graham W, Woodd S, Byass P, Filippi V, Gon G, Virgo S, Chou D, Hounton S, Lozano R, Pattinson R, Singh S. Diversity and divergence: the dynamic burden of poor maternal health. Lancet. 2016 Dec 29;388(10056):2164–2175. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31533-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, Tunçalp Ö, Moller A, Daniels J, Gülmezoglu AM, Temmerman M, Alkema L. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014 Jun;2(6):e323–33. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70227-X. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2214-109X(14)70227-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ollerhead E, Osrin D. Barriers to and incentives for achieving partograph use in obstetric practice in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014 Aug 16;14:281. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-281. https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2393-14-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balikuddembe MS, Byamugisha JK, Sekikubo M. Impact of decision to operation interval on pregnancy outcomes among mothers who undergo emergency caesarean section at Mulago hospital. J US China Med Sci. 2011 Sep;8(9):571–5. https://www.davidpublishing.com/DownLoad/?id=4488. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogwang S, Karyabakabo Z, Rutebemberwa E. Assessment of partogram use during labour in Rujumbura Health Sub District, Rukungiri District, Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2009 Aug 1;9(Suppl 1):S27–34. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/20589158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Windrim R, Seaward PG, Hodnett E, Akoury H, Kingdom J, Salenieks ME, Fallah S, Ryan G. A randomized controlled trial of a bedside partogram in the active management of primiparous labour. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2007 Jan;29(1):27–34. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)32367-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Bank Worldbank. 2012. Uganda makes progress on maternal health but serious challenges remain http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2012/10/23/uganda-makes-progress-on-maternal-health-but-serious-challenges-remain .

- 8.Lavender T, Hart A, Smyth RM. Effect of partogram use on outcomes for women in spontaneous labour at term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Aug 15;(8):CD005461. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005461.pub3. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22895950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fistula Care and Maternal Health Task Force . Bettercaretogether. New York: EngenderHealth/Fistula Care; 2012. Revitalizing the partograph: does the evidence support a global call to action? New YorkngenderHealth/Fistula Care 2012; http://www.bettercaretogether.org/sites/default/files/resources/EngenderHealth-Fistula-Care-Partograph-Meeting-Report-9-April-12.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okokon IB, Oku AO, Agan TU, Asibong UE, Essien EJ, Monjok E. An evaluation of the knowledge and utilization of the partogragh in primary, secondary, and tertiary care settings in calabar, South-South Nigeria. Int J Family Med. 2014;2014:105853. doi: 10.1155/2014/105853. doi: 10.1155/2014/105853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weerasekara D. Usefulness of a partograph to improve outcomes: scientific evidence. Sri Lanka J Obstet & Gynae. 2014;36(2):29–31. doi: 10.4038/sljog.v36i2.7449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orhue A, Ande A, Aziken M. Barriers to the universal application of the partograph for labour management: a review of the issues and proposed solutions. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011 Oct;28(1):32–42. [Google Scholar]

- 13.International Confederation of Midwives Partograph side meeting position statement. ICM Congress; 2014; Prague. 2014. http://www.mchip.net/sites/default/files/ICM%20Partograph%20Meeting%20Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amoroso C, Arango J, Bailey C, Blaya J, Fraser H, Gakuba R, Geissbuhler A, Israelski D, Khoja S, Labrique A, Lee B, Marcelo A, Mechael P, Mehl G, Murthy N, Orser R, Richards J, Schweitzer J, Sinha C, Were M, Wyatt J. A call to action on global eHealth evaluation. Bellagio eHealth Evaluation Meeting; 2011; Bellagio. 2011. https://www.ghdonline.org/uploads/The_Bellagio_eHealth_Evaluation_Call_to_Action-Release.docx. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blaya JA, Fraser HS, Holt B. E-health technologies show promise in developing countries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010 Feb;29(2):244–51. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0894. http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=20348068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kortteisto T, Raitanen J, Komulainen J, Kunnamo I, Mäkelä M, Rissanen P, Kaila M, EBMeDS (Evidence-Based Medicine electronic Decision Support) Study Group Patient-specific computer-based decision support in primary healthcare--a randomized trial. Implement Sci. 2014;9:15. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-9-15. http://www.implementationscience.com/content/9//15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall CS, Fottrell E, Wilkinson S, Byass P. Assessing the impact of mHealth interventions in low- and middle-income countries--what has been shown to work? Glob Health Action. 2014;7:25606. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.25606. http://www.globalhealthaction.net/index.php/gha/article/view/25606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kruk ME, Kujawski S, Moyer CA, Adanu RM, Afsana K, Cohen J, Glassman A, Labrique A, Reddy KS, Yamey G. Next generation maternal health: external shocks and health-system innovations. Lancet. 2016 Dec 05;388(10057):2296–2306. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31395-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien K, Colquhoun H, Kastner M, Levac D, Ng C, Sharpe JP, Wilson K, Kenny M, Warren R, Wilson C, Stelfox HT, Straus SE. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016 Feb 09;16:15. doi: 10.1186/s12874-016-0116-4. https://bmcmedresmethodol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12874-016-0116-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharafoddini A, Dubin JA, Lee J. Patient similarity in prediction models based on health data: a scoping review. JMIR Med Inform. 2017 Mar 03;5(1):e7. doi: 10.2196/medinform.6730. http://medinform.jmir.org/2017/1/e7/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blank A, Prytherch H, Kaltschmidt J, Krings A, Sukums F, Mensah N, Zakane A, Loukanova S, Gustafsson LL, Sauerborn R, Haefeli WE. “Quality of prenatal and maternal care: bridging the know-do gap” (QUALMAT study): an electronic clinical decision support system for rural Sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013 Apr 10;13:44. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-44. https://bmcmedinformdecismak.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1472-6947-13-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laerdal Laerdalglobalhealth. 2014. [2016-11-04]. Moyo fetal heart rate monitor http://www.laerdalglobalhealth.com/doc/2555/Moyo-Fetal-Heart-Rate-Monitor .

- 23.Schweers J, Khalid M, Underwood H, Bishnoi S, Chhugani M. mLabour: design and evaluation of a mobile partograph and labor ward management application. Procedia Eng. 2016;159:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2016.08.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharf Y, Farine D, Batzalel M, Megel Y, Shenhav M, Jaffa A, Barnea O. Continuous monitoring of cervical dilatation and fetal head station during labor. Med Eng Phys. 2007 Jan;29(1):61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Underwood H, Sterling SR, Bennett JK. The design and implementation of the partopen maternal health monitoring system. ACM Digital Library; Proceedings of the 3rd ACM Symposium on Computing for Development; January 11 - 12, 2013; Bangalore, India. ACM; 2013. pp. 1–10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Underwood H, Sterling SR, Bennett JK. Improving maternal labor monitoring in Kenya using digital pen technology: a user evaluation. Global Humanitarian Technology Conference (GHTC), 2012 IEEE; Oct 21 - 24, 2012; Seattle, WA, USA. IEEE; 2012. Dec, http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6387062/ [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dalaba MA, Akweongo P, Aborigo RA, Saronga HP, Williams J, Blank A, Kaltschmidt J, Sauerborn R, Loukanova S. Cost-effectiveness of clinical decision support system in improving maternal health care in Ghana. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125920. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125920. http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0125920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mensah N, Sukums F, Awine T, Meid A, Williams J, Akweongo P, Kaltschmidt J, Haefeli WE, Blank A. Impact of an electronic clinical decision support system on workflow in antenatal care: the QUALMAT eCDSS in rural health care facilities in Ghana and Tanzania. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:25756. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.25756. http://www.globalhealthaction.net/index.php/gha/article/view/25756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Su C, Chu T. A mobile multi-agent information system for ubiquitous fetal monitoring. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014 Jan 02;11(1):600–25. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110100600. http://www.mdpi.com/resolver?pii=ijerph110100600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brocklehurst P. A study of an intelligent system to support decision making in the management of labour using the cardiotocograph - the INFANT study protocol. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016 Jan 20;16:10. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0780-0. https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-015-0780-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Souza JP, Oladapo OT, Bohren MA, Mugerwa K, Fawole B, Moscovici L, Alves D, Perdona G, Oliveira-Ciabati L, Vogel JP, Tunçalp Ö, Zhang J, Hofmeyr J, Bahl R, Gülmezoglu AM, WHO BOLD Research Group The development of a Simplified, Effective, Labour Monitoring-to-Action (SELMA) tool for Better Outcomes in Labour Difficulty (BOLD): study protocol. Reprod Health. 2015 May 26;12(1) doi: 10.1186/s12978-015-0029-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hasan J, Hossain T, Arafat Y, Karim G, Ahmed Z, Mafi MS. Mobile application can be an effective tool for reduction of maternal mortality. International Journal of Perceptions in Public Health. 2017 Mar;1(2):92–94. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dekel S, Mandel B. jhpiego. ePartogram: 2013. [2016-11-04]. A mobile decision support tool to address labour complications https://www.jhpiego.org/video/epartogram-a-mobile-decision-support-tool/ [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams D, Ivey T, Benton T, Rhoads S. Another set of eyes: Remote fetal monitoring surveillance aids the busy labor and delivery unit. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2010 Sep;39:S41. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2010.01119_30.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Day K, Kenealy TW, Sheridan NF. Should we embed randomized controlled trials within action research: arguing from a case study of telemonitoring. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016 Jun 08;16:70. doi: 10.1186/s12874-016-0175-6. https://bmcmedresmethodol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12874-016-0175-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell OMR, Calvert C, Testa A, Strehlow M, Benova L, Keyes E, Donnay F, Macleod D, Gabrysch S, Rong L, Ronsmans C, Sadruddin S, Koblinsky M, Bailey P. The scale, scope, coverage, and capability of childbirth care. Lancet. 2016 Dec 29;388(10056):2193–2208. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31528-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koblinsky M, Moyer CA, Calvert C, Campbell J, Campbell OMR, Feigl AB, Graham WJ, Hatt L, Hodgins S, Matthews Z, McDougall L, Moran AC, Nandakumar AK, Langer A. Quality maternity care for every woman, everywhere: a call to action. Lancet. 2016 Dec 05;388(10057):2307–2320. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31333-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaw D, Guise J, Shah N, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Joseph KS, Levy B, Wong F, Woodd S, Main EK. Drivers of maternity care in high-income countries: can health systems support woman-centred care? Lancet. 2016 Dec 05;388(10057):2282–2295. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31527-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.English LL, Dunsmuir D, Kumbakumba E, Ansermino JM, Larson CP, Lester R, Barigye C, Ndamira A, Kabakyenga J, Wiens MO. The paediatric risk assessment (para) mobile app to reduce postdischarge child mortality: design, usability, and feasibility for health care workers in Uganda. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016 Feb 15;4(1):e16. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.5167. http://mhealth.jmir.org/2016/1/e16/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Daudt HM, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team's experience with Arksey and O'Malley's framework. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-48. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/13/48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]