Abstract

There are certain criteria to recommend surgical excision for lobular neoplasia diagnosed in mammographically detected core biopsy. The aims of this study are to explore the rate of upgrade of lobular neoplasia detected in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-guided biopsy and to investigate the clinicopathological and radiological features that could predict upgrade. We reviewed 1655 MRI-guided core biopsies yielding 63 (4%) cases of lobular neoplasia. Key clinical features were recorded. MRI findings including mass vs non-mass enhancement and the reason for biopsy were also recorded. An upgrade was defined as the presence of invasive carcinoma or ductal carcinoma in situ in subsequent surgical excision. The overall rate of lobular neoplasia in MRI-guided core biopsy ranged from 2 to 7%, with an average of 4%. A total of 15 (24%) cases had an upgrade, including 5 cases of invasive carcinoma and 10 cases of ductal carcinoma in situ. Pure lobular neoplasia was identified in 34 cases, 11 (32%) of which had upgrade. In this group, an ipsilateral concurrent or past history of breast cancer was found to be associated with a higher risk of upgrade (6/11, 55%) than contralateral breast cancer (1 of 12, 8%; P = 0.03). To our knowledge, this is the largest series of lobular neoplasia diagnosed in MRI-guided core biopsy. The incidence of lobular neoplasia is relatively low. Lobular neoplasia detected in MRI-guided biopsy carries a high risk for upgrade warranting surgical excision. However, more cases from different types of institutions are needed to verify our results.

Epidemiologic studies have shown that lobular neoplasia (atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH) and lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS)) is a marker of increased risk of developing breast cancer.1–3 LCIS is associated with ∼ 10 to 20% risk of developing invasive breast cancer in either breast over 15 years.4,5 It has been suggested that lobular neoplasia is a non-obligate precursor in the progression to invasive carcinoma.6–9 It is often multicentric and bilateral.10,11 Although the majority of cases have no mammographically distinctive features, some cases present with microcalcifications.

The incidence of lobular neoplasia diagnosed in core biopsy performed for a mammographic finding is rare, about 0.7%.12 The management of lobular neoplasia in core biopsy has received considerable attention in recent years. The upgrade rate to either ductal carcinoma in situ or invasive carcinoma is variable, with prior studies showing upgrade rates ranging from 0 to 35%.13 Therefore, there is debate as to whether lobular neoplasia found in core biopsy requires excision for optimal management.

The World Health Organization task force has published consensus that excision should be performed if there is another lesion that by itself would warrant excision or if there is pathological-imaging discordance. In cases where ALH or LCIS in core biopsy is a completely incidental finding, radiological-pathological correlation is recommended for determining further management. The World Health Organization task force recommends that excision should be performed for cases of classic LCIS with comedonecrosis, bulky mass-forming LCIS lesions and cases with pleomorphic LCIS (PLCIS) identified in core biopsy.14 In contrast, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend excision of any LCIS identified in core biopsy, even in the absence of other proliferative changes.15

Breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is increasingly being used for screening of women at high risk for breast cancer and preoperative evaluation of women with known breast cancer, as well as a number of additional indications.16 Specifically, women with a prior diagnosis of LCIS are considered to be at higher risk of developing breast cancer and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines advise consideration of annual screening MRI.17 In these women, MRI is not used for the detection of lobular neoplasia but for the detection of an otherwise occult cancer. Generally, lobular neoplasia is considered to be occult by MRI, although there are reports of cases with associated MRI findings.18

The incidence, rate of upgrade, clinical presentation, and the type of concurrent lesions of lobular neoplasia diagnosed in MRI-guided core biopsy have not been studied. That is mainly because of its rarity and relative infrequent use of MRI compared with mammography in diagnosing breast lesions. The purpose of this study is to address these issues on a large cohort of cases from several academic institutions.

Materials and methods

Cases

This is a multi-institutional collaborative study of lobular neoplasia diagnosed in core biopsy at four academic institutions namely: Roswell Park Cancer Institute (RPCI) at Buffalo, NY, USA; Magee Women's Hospital of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) at Pittsburgh, PA, USA; Washington University (WU) at Saint Louis, MO, USA; and Montefiore Medical Center (MMC) at New York City, NY, USA. After identifying the cases with a diagnosis of lobular neoplasia, the slides were reviewed by the working specialized breast pathologist(s) at each institution to confirm the diagnosis and record other histologic features such as flat epithelial atypia, atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH), papilloma, and/or radial scar. A case was considered mixed when at least one additional high-risk histologic finding was identified, including ADH, flat epithelial atypia, papilloma, and/or radial scar. At RPCI, the radiology records were searched for breast MRI-guided biopsy yielding 358 cases. The pathology reports were reviewed. Twenty six cases had a diagnosis of lobular neoplasia, which were confirmed by the breast pathologist (TK). Cases were retrieved from the UPMC through a computer-based search in CoPath for the words ‘breast MRI core biopsy’ yielding 862 cases, 29 of which had a diagnosis of lobular neoplasia, confirmed by the breast pathologists (ZL and MMD). Cases were retrieved from the WU through a computer-based search in CoPath for the words ‘MRI’ in all fields and ‘core biopsy’ and ‘breast’ in final diagnosis field yielding 335 cases, 5 of which had lobular neoplasia, which were confirmed by the breast pathologist (SS). For MMC cases, search of the Picture Archiving and Communication System yielded 100 cases of MRI-guided core biopsy. The pathology reports were reviewed for a diagnosis of lobular neoplasia yielding three cases. The slides of these cases were reviewed by the breast pathologist (RK) confirming the diagnosis.

Demographic data including age, race, hormonal use, previous or concurrent history of cancer, and menopausal status were collected for each patient.

Histologic Interpretation

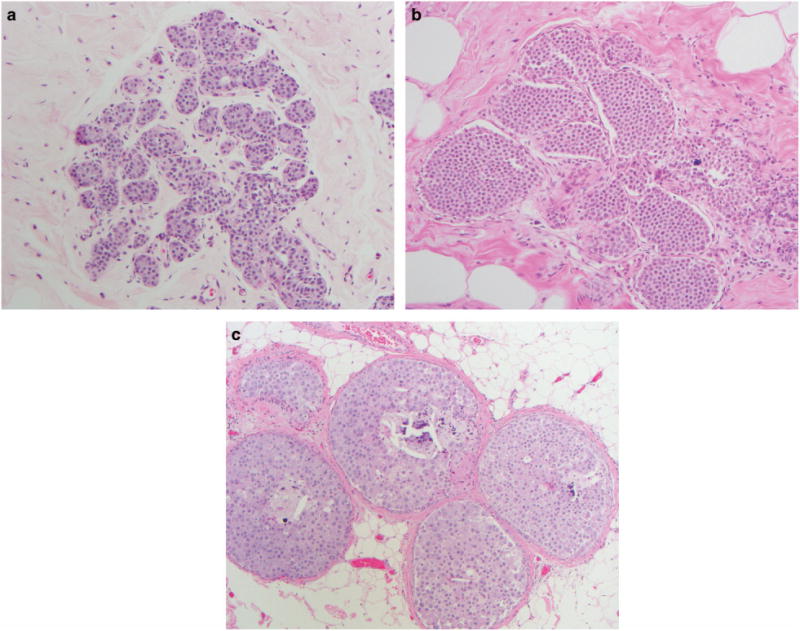

The cases were classified as ALH, LCIS, or PLCIS following the World Health Organization criteria.14 LCIS and ALH both have identical cytomorphologic features (small loosely cohesive neoplastic epithelial cells within the terminal ductal lobular unit). They differ in the degree of terminal ductal lobular unit expansion, where the terminal ductal lobular unit is filled and distended in LCIS unlike ALH (Figures 1a and b). PLCIS is defined based on the presence of high-grade cytomorphology, necrosis, and macroacinus formation (Figure 1c). Necrosis was defined as the presence of central zonal (comedo)-type necrosis in at least one duct. Macroacinic feature was defined as a massive degree of acinar distention to the point that the acini appeared almost confluent and the stroma barely evident in at least two acini. The cells were considered large (grade III nuclei) when their size was at least four times larger than that of a mature lymphocyte.19 Concurrent lesions that normally warrant surgical intervention were also recorded including flat epithelial atypia, ADH, papilloma, and radial scar.

Figure 1.

Various types of lobular neoplasia; (a) ALH with dyshesive small cells involving and partially filling terminal ductal lobular unit (hematoxylin and eosin × 20); (b) LCIS similar cells like in ALH but the cells fill and expand the terminal ductal lobular unit (hematoxylin and eosin × 20); (c) PLCIS with expanded back-to-back ducts filled with large pleomorphic dyshesive and apocrine cells with central necrosis and microcalcifications resembling ductal carcinoma in situ (hematoxylin and eosin × 10). ALH, atypical lobular hyperplasia; LCIS, lobular carcinoma in situ; PLCIS, pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in situ.

The excisional specimens which were performed within a maximum of 3 months were reviewed. The type of an upgrade including ductal carcinoma in situ, invasive carcinoma of no special type and invasive lobular carcinoma was recorded. To ensure that the targeted lesion was removed, we evaluated for the presence of the previous biopsy site. When the excisional biopsy has concurrent ipsilateral cancer, the pathology report was reviewed to ensure the correct site of the core biopsy within the lobular neoplasia. All cases of lobular neoplasia detected by MRI-guided biopsy at all four institutions were excised.

When the patient presented with concurrent ipsilateral carcinoma, verification from the pathology report and histological review was required to ensure that the lesion is not contiguous to the main tumor. In order to verify that, two biopsy sites had to be recognized, corresponding to each of the two lesions (the main tumor and the studied biopsy with lobular neoplasia) and had to be separated by non-involved breast tissue. All cases with concurrent ipsilateral breast cancer were found to be eligible for this study.

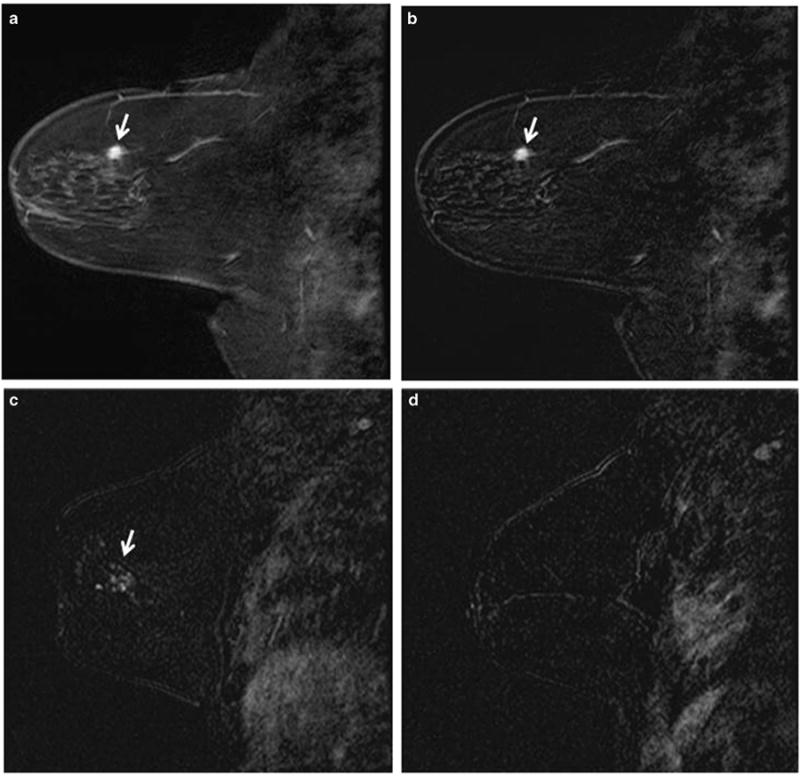

Radiologic Interpretation

Contrast-enhanced MRI studies performed immediately before the MRI-guided biopsy were reviewed and the findings of mass vs non-mass enhancement were recorded (Figure 2). The images were reviewed by the radiologist in RPCI (PK) and MMC (BR). The radiology variables were abstracted from the radiology reports in WU and UPMC. Second-look ultrasound was performed before MRI-guided biopsy as per the institutional protocol if the imaging finding was a mass, but not in cases of non-mass enhancement. For all institutions, the radiology biopsy report was reviewed to determine the number of cores obtained and the gauge of the biopsy needle. In addition, the clinical indication for the MRI, e.g., staging, high-risk screening, or clinical findings was recorded.

Figure 2.

Mass (a and b) and non-mass enhancement (c and d); a and b, sagittal fat-saturated Tl-weighted post-contrast image of the breast (a) and subtraction image of the same slice (b) demonstrate a 1.2 cm irregular mass (arrows); c and d, sagittal post-contrast subtraction image of the breast demonstrates 1.4 cm non-mass enhancement (c, arrow). In comparison, there was no enhancement in the other breast (d)

Statistical Analysis

In the univariate statistical analysis, the outcome upgrade was correlated with predictors using Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon non-parametric test for continuous variables, at a nominal significance level of 0.05. Multiple analyses were performed, one including all cases from all institutions, one including pure lobular neoplasia (excluding other types of atypia), one including only UPMC cases, and one including RPCI cases. The statistical analysis was performed using R version 3.0.1 (http://www.r-project.org).

Results

Table 1 illustrates the case distribution among different participating institutions. RPCI and UPMC contributed >85% of the cases. The incidence of lobular neoplasia at RPCI was higher (7%) compared with that at the UPMC (3.36%; P< 0.0014).

Table 1. Cases distribution among different institutions.

| Institution | Total No. (%) | LN No. (%) | Upgrade No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roswell Park Cancer Institute | 358 (22) | 26 (7) | 7 (27) |

| University of Pittsburgh Medical | 862 (52) | 29 (3) | 8 (28) |

| Center | |||

| Washington University | 335 (20) | 5 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Montefiore Medical Center | 100 (6) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 1655 (100) | 63 (4) | 15 (24) |

Abbreviation: LN, lobular neoplasia.

When all cases (pure and mixed) were included in the analysis, 63 (4%) cases were identified. Fifteen (24%) cases had upgrade, 3 invasive lobular carcinoma, 10 ductal carcinoma in situ, and 2 invasive carcinoma of no special type. There were 29 (46%) ALH, 31 (49%) LCIS, and 3 (5%) PLCIS. The rate of upgrade in these groups was 4 (13%), 9 (29%), and 2 (67%), respectively. The median patient age was 52 (range 38–79) years. There was no statistically significant difference with regard to age, menopausal status, MRI finding (mass vs non-mass), clinical indication for MRI, type of upgrade (invasive lobular carcinoma vs invasive carcinoma of no special type/ductal carcinoma in situ) or history of breast cancer (Table 2).

Table 2. Clinicopathological and radiological variables correlation with upgrade for all 63 cases.

| Upgrade | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Yes (n = 15) | No (n = 48) | |

| Age (mean and range) | ||

| 52 (38,79) years | 52 (41,72) years | 52 (38,79) yea |

| Race | ||

| African American (n = 4) | 1 (7) | 3 (6) |

| Caucasian (n =59) | 14 (93) | 45 (94) |

| Menopause status | ||

| Post (n =31)a | 7 (47) | 24 (50) |

| Pre (n = 29) | 8 (53) | 21 (25) |

| Mass vs non-mass | ||

| Mass (n = 24) | 3 (20) | 21 (25) |

| Non-mass (n = 39) | 12 (80) | 27 (56) |

| Reason for MRI | ||

| BIRAD 3 (n = 6) | 1 (6.7) | 5 (10) |

| Staging (n = 28) | 8 (53) | 20 (42) |

| High risk (n = 28) | 6 (40) | 22 (46) |

| Clinical (n = 1) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| ILC vs IC-NST or DCIS | ||

| IC-NST or DCIS (n = 32) | 5 (33) | 27 (56) |

| ILC (n = 10) | 4 (27) | 6 (13) |

| Concurrent vs past | ||

| Concurrent (n = 32) | 6 (40) | 26 (54) |

| Past (n = 10) | 3 (20) | 7 (15) |

| Ipsilateral vs contralateral | ||

| Contralateral (n = 20) | 2 (13) | 18 (38) |

| Ipsilateral (n = 22) | 7 (47) | 15 (31) |

| Pure LN vs mixedb | ||

| Mixed (n = 29) | 4 (27) | 25 (52) |

| Pure (n = 34) | 11 (73) | 23 (48) |

Abbreviations: DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; IC-NST, invasive carcinoma of no special type; ILC, invasive lobular carcinoma; LN, lobular neoplasia; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Three patients were perimenopausal.

LN mixed with other types of atypia. All of the comparisons were not statistically significant.

Pure lobular neoplasia was identified in 34 cases, whereas mixed lobular neoplasia with associated other high-risk lesion such as ADH, flat epithelial atypia, papilloma, and/or radial scar was seen in 29 cases. There were 12 cases mixed with ADH, 2 with flat epithelial atypia/ADH, 5 with flat epithelial atypia, 2 with papilloma, 5 with radial scar, 1 with papilloma/radial scar, 1 with ADH/papilloma/radial scar, and 1 with ADH/radial scar/flat epithelial atypia. The rate of upgrade in pure lobular neoplasia was higher than lobular neoplasia mixed with other high-risk lesion, 11 (32%) vs 4 (14%), respectively, with no statistical significance. When considering pure lobular neoplasia, there were 14 (41%) ALH cases, 17 (50%) LCIS, and 3 (9%) PLCIS. The rate of upgrade in these groups was 3 (21%), 6 (35%), and 2 (67%), respectively. Ipsilateral, concurrent, or past history of breast cancer was found to be a higher risk of upgrade than contralateral (concurrent or past), 6 of 11 (55%) vs 1 of 12 (8%), respectively (P = 0.03). The rest of the variables were not statistically significant (Table 3).

Table 3. Clinicopathological and radiological variables correlation with upgrade for pure LN cases.

| Variables | Upgrade | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Yes (n = 11) | No (n = 23) | ||

| Age (mean and range) | |||

| 52 (41,77) years | 51 (41,72) years | 52 (41,77) years | NS |

| Race | |||

| African American (n = 1) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | NS |

| Caucasian (n = 33) | 11 (100) | 22 (96) | |

| Menopause status | |||

| Post (n = 13)a | 4 (36) | 9 (39) | NS |

| Pre (n = 19) | 7 (64) | 12 (52) | |

| Mass vs non-mass | |||

| Mass (n = 12) | 2 (18) | 10 (44) | NS |

| Non-mass (n = 22) | 9 (82) | 13 (57) | |

| Reason for MRI | |||

| BIRAD 3 (n = 4) | 1 (9) | 3 (13) | NS |

| Clinical (n = 11) | 4 (36) | 7 (30) | |

| High risk (n = 18) | 6 (55) | 12 (52) | |

| Staging (n = 1) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.3) | |

| ILC vs IC-NST or DCIS | |||

| IC-NST or DCIS (n = 16) | 4 (36) | 12 (52) | NS |

| ILC (n = 7) | 3 (27) | 4 (17) | |

| Concurrent vs past | |||

| Concurrent (n = 18) | 5 (46) | 13 (57) | NS |

| Past (n = 5) | 2 (18) | 3 (13) | |

| Ipsilateral vs contralateral | |||

| Contralateral (n = 12) | 1 (9) | 11 (48) | 0.03 |

| Ipsilateral (n = 11) | 6 (55) | 5 (22) | |

Abbreviations: DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; IC-NST, invasive carcinoma of no special type; ILC, invasive lobular carcinoma; LN, lobular neoplasia; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NS, not significant.

Two patients were perimenopausal.

Table 4 lists all cases with pure lobular neoplasia with clinical/pathological and radiological findings. When MRI was performed for staging owing to concurrent ipsilateral or contralateral carcinoma, the tumor histologic type in the upgrade is similar to the first detected cancer. There were three invasive lobular carcinomas, one invasive carcinoma of no special type, and one ductal carcinoma in situ.

Table 4. Clinical, pathological, and radiological findings of all 34 pure LN.

| Case# | Age (years) | Race | Menopause | History of breast cancer | Excision | MRI | Reason | Histology | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| C/I | C/C | P/I | P/C | ||||||||

| 1a | 60 | CA | Post | ILC | No | No | No | ILC | NME | Staging | LCIS |

| 2a | 66 | CA | Post | ILC | No | No | No | Benign | NME | Staging | LCIS |

| 3a | 63 | CA | Post | IC-NST | No | No | IC-NST | Benign | Mass | Staging | ALH |

| 4a | 46 | CA | Pre | No | ILC | No | No | ADH/LCIS | Mass | High risk | LCIS |

| 5a | 52 | CA | Pre | No | No | No | No | LCIS | NME | High risk | ALH |

| 6a | 44 | CA | Pre | DCIS | No | No | No | DCIS | NME | Staging | ALH |

| 7a | 52 | CA | Pre | No | No | No | No | DCIS | NME | High risk | LCIS |

| 8a | 46 | CA | Pre | IC-NST | No | No | No | LCIS | NME | Staging | ALH |

| 9a | 61 | CA | Post | No | IC-NST | No | No | ALH | NME | High risk | ALH |

| 10a | 72 | CA | Post | No | No | No | No | IC-NST | NME | High risk | ALH |

| 11a | 41 | CA | Pre | IC-NST | No | No | No | Benign | NME | Staging | ALH |

| 12a | 51 | CA | Pre | No | No | IC-NST | No | IC-NST | NME | High risk | LCIS |

| 13a | 52 | CA | Pre | No | No | No | IC-NST | Benign | Mass | BIRAD 3 | ALH |

| 14b | 77 | CA | Post | No | ILC | No | No | LCIS | Mass | Staging | LCIS |

| 15c | 49 | CA | Pre | No | No | No | No | LCIS | NME | High risk | LCIS |

| 16c | 46 | CA | Pre | No | IC-NST | No | No | ALH | Mass | Staging | ALH |

| 17c | 42 | AA | Pre | No | IC-NST | No | No | Benign | Mass | Staging | LCIS |

| 18c | 64 | CA | Post | No | ILC | No | No | ALH | NME | Staging | ALH |

| 19d | 45 | CA | Pre | No | No | No | No | ALH | NME | High risk | ALH |

| 20d | 41 | CA | Pre | No | No | No | No | DCIS | NME | High risk | ALH |

| 21d | 52 | CA | Peri | No | No | No | No | ALH | NME | BI-RAD3 | ALH |

| 22d | 46 | CA | Pre | No | No | No | No | LCIS | Mass | High risk | LCIS |

| 23d | 59 | CA | Post | No | No | No | No | PLCIS | NME | High risk | PLCIS |

| 24d | 54 | CA | Post | No | No | IC-NST | No | LCIS | Mass | Staging | LCIS |

| 25d | 50 | CA | Pre | IC-NST | No | No | No | IC-NST | NME | Staging | LCIS |

| 26d | 61 | CA | Post | ILC | No | No | No | ILC | Mass | Staging | LCIS |

| 27d | 48 | CA | Pre | ILC | No | No | No | ILC | NME | Staging | PLCIS |

| 28d | 47 | CA | Pre | No | IC-NST | No | No | LCIS | Mass | Staging | LCIS |

| 29d | 63 | CA | Post | No | No | No | No | DCIS | Mass | BI-RAD3 | PLCIS |

| 30d | 41 | CA | Pre | No | No | No | IC-NST | DCIS | NME | Staging | LCIS |

| 31d | 43 | CA | Pre | No | No | No | IC-NST | LCIS | NME | Staging | LCIS |

| 32d | 55 | CA | Post | No | IC-NST | No | No | ALH | NME | Staging | LCIS |

| 33d | 52 | CA | Peri | No | No | No | No | ALH | Mass | BI-RAD3 | LCIS |

| 34d | 55 | CA | Post | No | IC-NST | No | No | LCIS | NME | Staging | ALH |

Abbreviations: AA, African American; ADH, atypical ductal hyperplasia; ALH, atypical lobular hyperplasia; CA, Caucasian American; C/C, concurrent contralateral; C/I, concurrent ipsilateral; DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; IC-NST, invasive carcinoma-no special type; ILC, invasive lobular carcinoma; LCIS, lobular carcinoma in situ; LN, lobular neoplasia; NME, non-mass enhancement; P/C, past contralateral; P/I, past ipsilateral; PLCIS, pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in situ.

RPCI.

MMC.

WU.

UPMC.

In both analyses (pure lobular neoplasia and mixed), LCIS had higher risk of upgrade than ALH with no statistical significant difference. Interestingly two of three PLCIS cases had upgrade.

When cases from RPCI and UPMC were separately analyzed, there were no statistically significant variables that could predict upgrade. However, MRI of all cases that had upgrade (n = 7) in RPCI group (n = 26) had non-mass enhancement with borderline significance (P =0.06). These two institutions were also compared in terms of the reason for MRI that detected lobular neoplasia. The reason for MRI at the RPCI was more often for staging (65%), whereas high risk was the main reason for UPMC (55%; P = 0.014; Table 5).

Table 5. Case distribution of all LN cases in Roswell Park Cancer Institute and Pittsburgh Medical Center with the reason of MRI and corresponding rate of upgrade.

| RPCI (n = 26) | Upgrade n (%) | UPMC (n = 29) | Upgrade n (%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIRAD 3 | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 5 (17) | 1 (20) | 0.014a |

| Staging | 17 (65) | 5 (29) | 8 (28) | 3 (38) | — |

| High risk | 8 (31) | 2 (25) | 16 (55) | 4 (25) | — |

| Mass | 9 (35) | 0 (0) | 12 (41) | 3 (25) | NSb |

| Non-mass | 17 (65) | 7 (41) | 17 (59) | 5 (29) | — |

Abbreviations: LN, lobular neoplasia; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NS, not significant.

P-value is for the difference in the reason of MRI: BIRAD 3, staging vs high risk between Roswell Park Cancer Institute and Pittsburgh Medical Center.

P-value is for the difference in the reason for upgrade between Roswell Park Cancer Institute and Pittsburgh Medical Center in terms of MRI type of enhancement (mass vs non-mass).

Discussion

We are reporting the largest series of lobular neoplasia identified in MRI-guided biopsy (n = 63) from the largest series of MRI-guided biopsies (n = 1655). This is the first study that distinguished between pure lobular neoplasia vs lobular neoplasia mixed with other pathological high-risk lesions. In addition, we were able to compare the incidence of lobular neoplasia and the reason for performing MRI between a cancer center and general hospital.

There are few published cases of lobular neoplasia found by MRI-guided core biopsy. The few reported cases have been identified either in studies of MRI-guided core biopsy outcomes or in the few studies on general high-risk lesion detected by MRI-guided core biopsy. The results of these studies are summarized in a review paper by Heller et al.20 The frequency of lobular neoplasia in seven studies was as follows: 4 of 95 (4%), 7 of 85 (8%), 1 of 55 (2%), 5 of 75 (7%), 9 of 482 (2%), 3 of 72 (4%), and 45 of 1145 (4%).21–27 The rate of upgrade in these studies combined (excluding the study by Heller et al20) was 4 of 26 (15%).

Heller et al20 reported the largest series of cases. They identified LCIS in 30 (3%) and ALH in 15 (1%) of 1145 cases. The incidence of lobular neoplasia was 45 (4%). The rate of upgrade was 8 of 30 (27%) for LCIS and 2 of 15 (13%) for ALH, with a total of 10 of 45 (22%) for both types of lobular neoplasia. However, it is unclear if these lesions were pure lobular neoplasia or mixed with other high-risk pathological findings.27 We found that the rate of upgrade for lobular neoplasia mixed with other high-risk histological findings was 24% and for pure lobular neoplasia was 32%.

In mammography-detected lobular neoplasia, the age of the majority of patients is between 40 and 50 years.28–31 In our MRI-examined patients, the median age was 52 years, which is older than in mammographically examined patients. This is likely because of the disparate populations undergoing mammography vs MRI. All women over the age of 40 years are eligible for mammography, as well as younger women who are symptomatic or at a higher risk. In contrast, MRI is used in a selected population that already has a breast cancer or high-risk diagnosis, or who requires supplemental screening.

The rate of upgrade for lobular neoplasia varies widely among studies.4 Therefore, it has not necessarily been recommended to routinely excise it. The consensus recommendation is to excise lesions that have certain clinical, radiological, or pathological characteristics that predict a higher risk of upgrade.14 Although the rate of upgrade for ADH also varies widely (from 7 to 87%),32–34 surgical excision is recommended more often, mainly owing to the sense that these lesions carry higher risk of upgrade than lobular neoplasia. In the same cohort of MRI-guided biopsies (n =1655) presented in this study, we detected 100 cases of ADH, 15 (15%) of which had upgrade. The results are presented in a separate study. There were 86 cases of pure ADH, 11 (13%) of which had upgrade. There were 14 cases of mixed ADH/lobular neoplasia, 4 of which had upgrade (29%).35 When all histologic types (pure lobular neoplasia, mixed lobular neoplasia/ADH, and pure ADH) were comparted, there was no statistically significant difference in the rate of upgrade. When the upgrade rate between pure lobular neoplasia (11 of 34) and pure ADH (11 of 86) was compared, the difference was borderline significant (P =0.042). We conclude that in MRI-guided biopsy the incidence of upgrade for pure lobular neoplasia is higher than pure ADH. Therefore, unlike mammography- detected lobular neoplasia, where certain recommendations were put in place by the World Health Organization to guide therapy, MRI-detected lobular neoplasia warrant surgical excision. Although we present the largest series of lobular neoplasia cases, more cases are needed to examine this finding.

Although controversial, there is a general agreement that the order of the rate of upgrade from low to high is ALH-LCIS-PLCIS.14 MRI-detected lobular neoplasia in this study had similar order. However, the number of cases in each category is too small, particularly for PLCIS (n = 3).

We found that in a cancer center like RPCI, the incidence of lobular neoplasia in MRI-detected core biopsy was higher than that of a general hospital like UPMC (Table 1). We also found that for the lobular neoplasia-positive MRI-guided core biopsies, the reason for MRI was statistically different between these two institutions (Table 5). In a general hospital like UPMC, MRI is more often performed for mammographic BIRAD 3 or as part of high-risk work-up, compared with a tertiary cancer center like RPCI where a staging indication is more common. That may partially explain why lobular neoplasia is more common in cancer centers than in general hospitals. A limitation of this study is that the indications for all 1655 MRI-guided core biopsies were not available.

Non-mass enhancement was found to have higher risk of upgrade than enhancing masses in RPCI cases with a borderline significance. In UPMC cases, there was no difference in terms of the type of enhancement. This difference could not be explained by the type of upgrade (ILC, IC-NST, ductal carcinoma in situ), as there was no difference in the incidence of these types of upgrades between both institutions (Table 5). As staging was more common in a cancer center than in a general hospital, we attempted to investigate if the risk of upgrade in non-mass- enhanced cases was independent from the reason for MRI. However, the number of cases became very small precluding this assessment. Moreover, the difference was just borderline statistically significant. Therefore, more cases are needed to investigate if non-mass enhancement is an independent factor of upgrade for lobular neoplasia.

It would be useful for future studies to investigate the radiological characteristics of the enhancement and correlate with the risk of upgrade, ie, including the type of enhancement in the non-mass lesion (focal, linear, or segmental) and the characteristics of mass lesions (margin, shape, and type of internal enhancement). These variables were not possible to study owing to the relative small sample size.

In conclusion, the incidence of lobular neoplasia in MRI-guided core biopsy is rare. The risk of upgrade is relatively high, warranting surgical excision. The difference in patient populations at a cancer center and a general hospital is reflected by the rate of upgrade, the reason for the biopsy and the radiological findings. Therefore, more cases from different hospital settings are needed to further explore our findings.

Footnotes

Disclosure/conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Bodian CA, Perzin KH, Lattes R. Lobular neoplasia. Long term risk of breast cancer and relation to other factors. Cancer. 1996;78:1024–1034. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960901)78:5<1024::AID-CNCR12>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chuba PJ, Hamre MR, Yap J, et al. Bilateral risk for subsequent breast cancer after lobular carcinoma in situ: analysis of surveillance, epidemiology, and end results data. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5534–5541. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins LC, Baer HJ, Tamimi RM, et al. Magnitude and laterality of breast cancer risk according to histologic type of atypical hyperplasia: results from the Nurses' Health Study. Cancer. 2007;109:180–187. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Malley FP. Lobular neoplasia: morphology, biological potential and management in core biopsies. Mod Pathol. 2010;23(Suppl 2):S14–S25. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arpino G, Laucirica R, Elledge RM. Premalignant and in situ breast disease: biology and clinical implications. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:446–457. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-6-200509200-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simpson PT, Gale T, Fulford LG, et al. The diagnosis and management of pre-invasive breast disease: pathology of atypical lobular hyperplasia and lobular carcinoma in situ. Breast Cancer Res. 2003;5:258–262. doi: 10.1186/bcr624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lakhani SR. In-situ lobular neoplasia: time for an awakening. Lancet. 2003;361:96. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mastracci TL, Shadeo A, Colby SM, et al. Genomic alterations in lobular neoplasia: a microarray comparative genomic hybridization signature for early neoplastic proliferation in the breast. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006;45:1007–1017. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Page DL, Schuyler PA, Dupont WD, et al. Atypical lobular hyperplasia as a unilateral predictor of breast cancer risk: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2003;361:125–129. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foote F, Stewart F. Lobular carcinoma in situ: a rare form of mammary cancer. Am J Pathol. 1941;17:491–496. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.32.4.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosen PP, Senie R, Schottenfeld D, et al. Noninvasive breast carcinoma: frequency of unsuspected invasion and implications for treatment. Ann Surg. 1979;189:377–382. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197903000-00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lechner MD, Park SL, Jackman RJ, et al. Lobular carcinoma in situ and atypical lobular hyperplasia at percutaneous biopsy with surgical correlation: a multiinstitutional study. Radiology. 1999;213:106. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaudhary S, Lawrence L, McGinty G, et al. Classic lobular neoplasia on core biopsy: a clinical and radiopathologic correlation study with follow-up excision biopsy. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:762–771. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lakhani SR, Schnitt SJ, O'Malley F, et al. Lobular neoplasia. In: Lakhani SR, Ellis IO, Schnitt SJ, Tan PH, van de Vijver MJ, editors. World Health Organization classification of tumors of the breast. 4th. International Agency of Research and Cancer (IARC); Lyon, France: 2012. pp. 78–80. [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (US) Clinical practice guidelines in oncology, breast cancer. Vol. 2. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (US); Fort Washington (PA): 2015. [accessed on 25 June 2015]. Available from http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuhl C. Current status of breast MR imaging Part 2. Radiology. 2007;244:672–691. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2443051661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bevers TB, Anderson BO, Bonaccio E, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: breast cancer screening and diagnosis. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7:1060–1096. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scoggins M, Krishnamurthy S, Santiago L, et al. Lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast: clinical, radiological, and pathological correlation. Acad Radiol. 2013;20:463–470. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khoury T, Karabakhtsian RG, Mattson D, et al. Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast: clinicopathological review of 47 cases. Histopathol. 2014;64:981–993. doi: 10.1111/his.12353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heller SL, Hernandez O, Moy L. Radiologic-pathologic correlation at breast MR imaging what is the appropriate management for high-risk lesions? Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2013;21:583–599. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liberman L, Bracero N, Morris E, et al. MRI-guided 9-gauge vacuum-assisted breast biopsy: initial clinical experience. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:183–193. doi: 10.2214/ajr.185.1.01850183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orel SG, Rosen M, Mies C, et al. MR imaging guided 9-gauge vacuum-assisted core-needle breast biopsy: initial experience. Radiology. 2006;238:54–61. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2381050050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahoney MC. Initial clinical experience with a new MRI vacuum-assisted breast biopsy device. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;28:900–905. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noroozian M, Gombos EC, Chikarmane S, et al. Factors that impact the duration of MRI-guided core needle biopsy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:W150–W157. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strigel RM, Eby PR, Demartini WB, et al. Frequency, upgrade rates, and characteristics of high-risk lesions initially identified with breast MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:792–798. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.4081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malhaire C, El Khoury C, Thibault F, et al. Vacuum assisted biopsies under MR guidance: results of 72 procedures. Eur Radiol. 2010;20:1554–1562. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1707-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heller SL, Elias K, Gupta A, et al. Outcome of high-risk lesions at MRI-guided 9-gauge vacuum- assisted breast biopsy. Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202:237–245. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.10600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wheeler JE, Enterline HT, Roseman JM, et al. Lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast. Long-term follow-up. Cancer. 1974;34:554–563. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197409)34:3<554::aid-cncr2820340313>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andersen JA. Lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast. An approach to rational treatment. Cancer. 1977;39:2597–2602. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197706)39:6<2597::aid-cncr2820390644>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosen PP, Kosloff C, Lieberman PH, et al. Lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast. Detailed analysis of 99 patients with average follow-up of 24 years. Am J Surg Pathol. 1978;2:225–251. doi: 10.1097/00000478-197809000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson BO, Calhoun KE, Rosen EL. Evolving concepts in the management of lobular neoplasia. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2006;4:511–522. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2006.0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ely KA, Carter BA, Jensen RA, et al. Core biopsy of the breast with atypical ductal hyperplasia. A probabilistic approach to reporting. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1017–1021. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200108000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagoner MJ, Laronga C, Acs G. Extent and histologic pattern of atypical ductal hyperplasia present on core needle biopsy specimens of the breast can predict ductal carcinoma in situ. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;131:112–121. doi: 10.1309/AJCPGHEJ2R8UYFGP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Houssami N, Ciatto S, Ellis I, et al. Underestimation of malignancy of breast core-needle biopsy. Cancer. 2007;109:487–495. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khoury T, Li Z, Sanati S et al. The risk of upgrade for atypical ductal hyperplasia detected on MRI-guided biopsy: a study of 100 cases from four academic institutions. Histopathol. 2015 doi: 10.1111/his.12811. ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]