Publisher's Note: There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

Key Points

Pembrolizumab was first shown to be clinically active in CLL patients with RT.

PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in tumor microenvironment are promising biomarkers to select RT patients for PD-1 blockade.

Abstract

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients progressed early on ibrutinib often develop Richter transformation (RT) with a short survival of about 4 months. Preclinical studies suggest that programmed death 1 (PD-1) pathway is critical to inhibit immune surveillance in CLL. This phase 2 study was designed to test the efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab, a humanized PD-1–blocking antibody, at a dose of 200 mg every 3 weeks in relapsed and transformed CLL. Twenty-five patients including 16 relapsed CLL and 9 RT (all proven diffuse large cell lymphoma) patients were enrolled, and 60% received prior ibrutinib. Objective responses were observed in 4 out of 9 RT patients (44%) and in 0 out of 16 CLL patients (0%). All responses were observed in RT patients who had progression after prior therapy with ibrutinib. After a median follow-up time of 11 months, the median overall survival in the RT cohort was 10.7 months, but was not reached in RT patients who progressed after prior ibrutinib. Treatment-related grade 3 or above adverse events were reported in 15 (60%) patients and were manageable. Analyses of pretreatment tumor specimens from available patients revealed increased expression of PD-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and a trend of increased expression in PD-1 in the tumor microenvironment in patients who had confirmed responses. Overall, pembrolizumab exhibited selective efficacy in CLL patients with RT. The results of this study are the first to demonstrate the benefit of PD-1 blockade in CLL patients with RT, and could change the landscape of therapy for RT patients if further validated. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT02332980.

Introduction

The landscape of treatment of relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) has changed with the introduction of novel signal inhibitors, including the Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib, the PI3Kδ inhibitor idelalisib, and the B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) inhibitor venetoclax.1-4 Despite the improved clinical outcomes, CLL patients continue to progress over time,1 and CLL patients who progressed early while receiving ibrutinib often developed Richter transformation (RT), a transformation into aggressive lymphoma. To date, CLL patients who developed RT while receiving ibrutinib have a very short overall survival (OS) (∼4 months)5,6 and this presents an unmet clinical need.

Interactions of programmed death 1 (PD-1) with its ligands represent a major immune checkpoint engaged by tumor cells to overcome active T-cell–immune surveillance. Humanized immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) monoclonal antibodies designed to block the interactions between PD-1 and its ligands have shown significant clinical activity in metastatic solid tumors7-12 and Hodgkin lymphoma (HL),13 but has yet to be extensively studied in relapsed CLL or RT.

Accumulating evidence has emerged in regards to the expression of PD-1 and its ligands in several types of non-HL (NHL), including CLL.14-18 Exhausted effector or effector memory T cells in CLL patients overexpress PD-1 and are defective to form immune synapse with leukemic B cells.19-21 Incubation of PD-1–blocking antibody with CLL T cells restores the normal immune synapse between peripheral T cells and CLL leukemic cells.19-21 Recent data has revealed that blocking the PD-1 pathway with PD-ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibody will abrogate CLL disease progression in a CLL mouse model (Tcl-1 transgenic).22,23 Preliminary clinical data showed the efficacy of PD-1 antibody in selected hematologic malignancies, including diffuse large BCL (DLBCL)24,25 and other NHLs.25,26

Given the above data, we hypothesized that blocking PD-1 interactions with its ligands would overcome immune evasion in patients with relapsed CLL and RT. To test this hypothesis, we conducted an investigator-initiated phase 2 clinical trial (#NCT02332980) to evaluate the safety and clinical activity of the PD-1–blocking antibody pembrolizumab in relapsed or refractory CLL and low-grade B-cell NHL (follicular, marginal zone, and lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma) patients. We also included the use of pembrolizumab in RT because ∼50% of patients with RT have TP53 disruption that typically associate with genomic instability,27,28 and cancers with high somatic mutation loads/genomic complexity tend to respond to PD-1 blockade.29 Here, we report the results in the CLL cohort of this phase 2 trial, including CLL patients with RT.

Methods

Patients

This study was conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Mayo Clinic. All patients provided written informed consent before study entry. This study was designed to accrue two parallel disease cohorts: cohort A included patients with relapsed or progressive CLL and CLL with RT, and cohort B included patients with low-grade B-cell NHL. These disease cohorts were analyzed independently. The results of cohort A are reported here; cohort B will be reported separately. For cohort A, patients had to be at least 18 years of age, have relapsed or refractory CLL (ie, at least one CLL therapy), an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score of 0 to 2, adequate hepatic and renal function, and progressive symptoms needing therapy based on the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (IWCLL) 2008 criteria.30 For CLL patients with RT, biopsy-proven high-grade lymphoma confirmed on Mayo Clinic hematopathology review and at least one measurable lesion >1.5 cm were required to be eligible for enrollment. Patients with baseline cytopenia but maintaining the following hematologic parameters, neutrophils ≥0.5 × 109/L and platelets ≥25 × 109/L, were eligible. Key exclusion criteria were: a history of allogeneic stem cell transplant (SCT), active autoimmune disease, a concomitant active second cancer, or a history of cancer involving the central nervous system.

Study design

The study agent, pembrolizumab, was IV administered at a fixed dose of 200 mg every 3 weeks for up to 2 years unless patients experienced progressive disease (PD) or excessive toxicities, or consent withdrawal. The primary end point of the trial was overall response rate (ORR), defined as the proportion of patients achieving a confirmed response to single-agent pembrolizumab. A confirmed response for RT was defined as a partial response (PR), partial metabolic response (PMR), complete response (CR), or complete metabolic response while receiving single-agent pembrolizumab, using the modified Cheson 2007 lymphoma criteria initially and then updated to the 2014 Lugano lymphoma response criteria.31,32 For CLL without RT, a confirmed response was considered PR or nodular PR, or CR or CR with incomplete marrow recovery or clinical CR, for relapsed CLL defined using the modified IWCLL 2008 criteria.30 Secondary objectives included safety analysis and evaluation of progression-free survival (PFS) and OS.

Patients were evaluated for safety assessments using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0 beginning at study entry and continuing until 30 days after administration of the last dose. Hematologic adverse events (AEs) were also graded using the CLL grading scale for hematologic toxicity from the IWCLL 2008 criteria.30 All patients who received ≥1 dose were included for analysis. Patients were evaluated at screening and at months 3, 6, and 12 for efficacy by computed tomography or 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose–positron emission tomography (PET), or as needed for clinical assessment. Bone marrow (BM) examination was performed at months 6 and 12, or as needed for clinical assessment for response.

Statistical analysis

This study used a 1-stage binomial trial design with a total sample size of 23 patients with 2 additional patients for potential replacement, and 86% power to detect an ORR increase from 10% to 30% at a 1-sided type I error rate of 7%. OS, PFS, and duration of response (DOR) probabilities were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier estimator. Plots of the percentage changes in tumor burden for each patient were presented graphically.

Biomarker assessment

Immunohistochemical (IHC) and immunofluorescent stains, in situ hybridization for Epstein-Barr virus-encoded RNA, and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to assess chromosome 9p24 (encoding PD-L1 and PDCD1LG2 encoding PD-L2) copy number were performed on 4 μm formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections of tumor as previously described (see supplemental Methods, available on the Blood Web site).13,33,34 The clonal relationship between CLL and RT tumor was assessed as previously reported.35,36 Genomic DNA isolated from sorted CLL leukemic B cells or large cell lymphoma tumor from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections, as well as sorted blood T cells (germ line) were used to perform DNA mismatch repair analysis as previously described.37 The absolute number of CD3, CD4, CD8, and naïve T cells, as well as a percentage of CD3, CD4, and CD8 T cells in lymphocytes and a percentage of naïve T cells in CD3+ T cells were assessed by standard flow cytometry at the baseline of trial enrollment as previously described.15,38

Results

Patients

The trial opened for enrollment in February 2015 and the analysis cutoff was end June 2016. A total of 25 patients had been enrolled: 16 with relapsed/refractory CLL (64%) and 9 with RT (all biopsy-proven DLBCL) (36%). The baseline characteristics of patients are presented in Table 1. The median age was 69 years (range, 46 to 81). Twelve patients (48%) had TP53 disruption: 9 (36%) had del(17p) or monosomy 17, and 3 (12%) had a TP53 somatic mutation without del(17p). Twenty-one patients (84%) had unmutated IGHV. The median number of prior therapies was 4 (range, 1 to 10). Fifteen (60%) patients had received prior ibrutinib, including 12 patients who progressed while receiving ibrutinib (6 patients who progressed with RT; 6 patients with progressive CLL). Three CLL patients discontinued prior ibrutinib therapy due to AEs (2 patients had bleeding events and 1 patient had recurrent symptomatic atrial fibrillation).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients

| RT* (n = 9) | CLL (n = 16) | Total (n = 25) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||

| Median | 69 | 72 | 69 |

| Range | (46-78) | (59-81) | (46-81) |

| ≥70 | 4 (44) | 9 (56) | 13 (52) |

| Sex, no. (%) | |||

| Male | 7 (78) | 10 (63) | 17 (68) |

| Female | 2 (22) | 6 (38) | 8 (32) |

| Race, white | 9 (100) | 16 (100) | 25 (100) |

| ECOG performance score, no. (%) | |||

| 0 | 3 (33) | 2 (13) | 5 (20) |

| 1 | 5 (56) | 12 (75) | 17 (68) |

| 2 | 1 (11) | 2 (13) | 3 (12) |

| Rai stage, no. (%) | |||

| 0-2 (low) | 3 (33) | 3 (19) | 6 (24) |

| 3-4 (high) | 6 (67) | 13 (81) | 19 (76) |

| CLL FISH,† no. (%) | |||

| del(17p)/-17 | 3 (33) | 6 (38) | 9 (36) |

| TP53+, no del(17p) | 2 (22) | 1 (6) | 3 (12) |

| del(11q) | 0 | 4 (25) | 4 (16) |

| +12 | 0 | 2 (13) | 2 (8) |

| del(13q) | 1 (11) | 2 (13) | 3 (12) |

| Normal | 3 (33) | 1 (6) | 4 (16) |

| IGHV, no. (%) | |||

| Mutated | 2 (22) | 2 (13) | 4 (16) |

| Unmutated | 7 (78) | 14 (88) | 21 (84) |

| Previous therapies, no. (%) | |||

| Median | 5 | 3.5 | 4 |

| Range | (1,10) | (1,9) | (1,10) |

| Prior alkylator | 8 (89) | 16 (100) | 24 (96) |

| Prior anti-CD20 | 8 (89) | 16 (100) | 24 (96) |

| Prior purine analog | 5 (56) | 13 (81) | 18 (72) |

| Prior anthracycline | 6 (67) | 6 (38) | 12 (48) |

| Prior ibrutinib | 6 (67) | 9 (56) | 15 (60) |

| Progression on ibrutinib/idelalisib | 6 (67) | 6 (38) | 12 (48) |

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IGHV, immunoglobulin heavy chain variable.

All RT enrolled are DLBCL transformation confirmed by biopsy. Three out of 9 RT did not receive RT-directed chemotherapy before pembrolizumab treatment.

CLL FISH classification is per the Dohner hierarchy.

Safety

AEs were reported in all 25 patients. Treatment-related grade 3 (G3) or above AEs were reported in 15 (60%) patients. Drug-related AEs that occurred in at least 5% of the patients are listed in Table 2. All AEs deemed to be related or unrelated to the drug are included in supplemental Table 1. Twenty-four (96%) or 16 (64%) patients had baseline anemia or thrombocytopenia. The most frequent treatment-related G3/G4 AEs were thrombocytopenia (20%), anemia (20%), neutropenia (20%), and dyspnea and hypoxia (8% each) (Table 2). Serious AEs regardless of attribution included: 3 G3 lung infections (12%, all resolved with antibiotic therapy; 1 was determined to be related); 2 G3 hepatic toxicities (increased liver enzymes or bilirubin, 8%, resolved after brief steroid therapy; 1 was determined to be related and discontinued therapy); 2 G2 pneumonitis (8%, resolved after brief interruption of therapy); and 2 early deaths (8%), which occurred during the first cycle of therapy. One death possibly related to treatment occurred in a CLL patient who had baseline neutropenia and had multiple prior therapies, including pentostatin, cyclophosphamide, rituximab, bendamustine, and fludarabine. Approximately 1 week after the first dose of pembrolizumab, a cough developed and symptoms escalated to Pseudomonas sepsis with respiratory failure and cardiac arrest. Despite maximal resuscitation effort, the patient died 9 days after receiving 1 dose of pembrolizumab. The second death occurred in a CLL patient who went off treatment due to failure to thrive unrelated to therapy and received palliative care. One patient (4%) developed G2 cytokine-release syndrome after the first dose of therapy, which resolved after brief steroid therapy. The median number of pembrolizumab cycles administered was 3 (range, 1 to 20), and the median treatment duration was 11 weeks (range, 1 to 56). The median treatment duration for patients with CLL and RT cohort were 7.5 and 13 weeks, respectively.

Table 2.

Drug-related AEs in at least 5% of patients

| AE | G1-G2 | G3-G4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Platelet count decreased | 6 | 24 | 5 | 20 |

| Anemia | 5 | 20 | 5 | 20 |

| Neutrophil count decreased | 4 | 16 | 5 | 20 |

| Cough | 7 | 28 | 0 | 0 |

| Dyspnea | 4 | 16 | 2 | 8 |

| Fatigue | 3 | 12 | 2 | 8 |

| Nausea | 5 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 3 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 3 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| Febrile neutropenia | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| Chills | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Fever | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| Hypoxia | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| Rash maculo-papular | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

Decisions on whether the AE was related to the study drug were made by the treating physicians/investigators. A more detailed list of all AEs is provided in supplemental Table 1. n = 25.

Clinical activity

Of the entire cohort of 25 patients, only RT patients had a confirmed response. No CLL patient had a confirmed response to pembrolizumab. One RT patient achieved a CR (11%), 3 RT patients had PMR (33%) including 2 with a ≥50% tumor reduction consistent with PR, 4 RT patients had stable disease (SD) (44%), and 1 RT patient had PD (11%). The ORR in the RT cohort was 44% (95% confidence interval [CI], 14-79). Among the 16 CLL patients, 3 patients were not evaluated due to the following reason: 2 early deaths before completion of the first cycle of therapy due to one drug-related sepsis and 1 unrelated failure to thrive (see “Safety”); 1 patient lost to follow-up after the first dose of treatment. Among 13 evaluable CLL patients without RT, 5 patients had SD and 8 had PD (Table 3). The ORR in the entire cohort was 16% (95% CI, 5-36). The changes in tumor burden and duration of therapy in all evaluated patients are shown in supplemental Figure 1. Four CLL patients had brief tumor reduction with a duration of <2 months, but all 4 patients had marrow disease progression and were not enough for classification as confirmed response per the IWCLL 2008 criteria. The remaining 9 CLL patients had PD due to either an increase of tumor burden or marrow CLL progression. It is noted that none of the CLL patients had confirmed responses to single-agent pembrolizumab whether or not they had developed clinical progression to prior ibrutinib therapy. All CLL patients discontinued therapy primarily secondary to lack of responses.

Table 3.

Clinical activity of pembrolizumab in trial patients

| Response | RT (n = 9) | CLL (n = 16) | Total (n = 25) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CR, no. (%) | 1 (11) | 0 | 1 (4) |

| PR, no. (%) | 2 (22) | 0 | 2 (8) |

| PMR, no. (%) | 1 (11) | 0 | 1 (4) |

| SD, no. (%) | 4 (44) | 5 (31) | 9 (36) |

| PD,* no. (%) | 1 (11) | 8 (50) | 9 (36) |

| Could not be evaluated,† no. (%) | 0 | 3 (19) | 3 (12) |

| ORR, % (95% CI) | 44 (14-79) | 0 (—) | 16 (5-36) |

| Median PFS, mo, (95% CI) | 5.4 (2.8-12.2) | 2.4 (1.2-3.3) | 3.0 (2.1-5.4) |

| Median OS, mo, (95% CI) | 10.7 (4.4-NR) | 11.2 (2.8-NR) | 10.7 (4.4-NR) |

NR, not reached.

Unfirmed PD (uPD) was included in the category of PD. uPD was defined that patients meet the criteria for PD based on the original PD criteria, but was not confirmed 4 weeks later. This criteria was developed into response criteria due to the unknown nature of potential pseudo-tumor progression/tumor flare reaction documented with immunotherapy (see details in the response criteria section in the supplemental Appendix).

Three patients were not evaluated due to the following reason: 2 early deaths before completion of the first cycle of therapy due to 1 drug-related sepsis and 1 unrelated failure to thrive; 1 lost to follow-up after the first dose of treatment.

Figure 1A shows the maximal reduction/increase in tumor burden from baseline in RT patients. Five of the 6 RT patients treated with pembrolizumab after prior ibrutinib had experienced a nodal reduction. The 1 patient (RS3) who did not have clear nodal reduction had predominant skin lymphoma at baseline and experienced a short duration (3 weeks) of disappearance of skin lesions. All RT patients completed ≥2 cycles of therapy and their duration of therapy is shown in Figure 1B. Clinical responses occurred early after 2 cycles of therapy in responding patients. Three RT patients (RS1, RS2, and RS9) continue to receive therapy and the median duration of therapy for patients who had confirmed responses was 8.3 months at the time of this report. Representative PET images for RS2 before and after 2 cycles of therapy are shown in Figure 1C. RS2 and RS6 achieved PR for their RT phase of disease, but both developed worse thrombocytopenia due to CLL marrow progression. Thus, the protocol was amended in January 2016 to allow the addition of idelalisib/ibrutinib to control the underlying CLL, and the addition of idelalisib in RS2 was associated with improvement of thrombocytopenia as shown in Figure 1D. Two patients (RS3 and RS7) who had SD elected to discontinue the study in order to undergo alternative therapy. RS6 had PRs to pembrolizumab before CLL marrow progression leading to G3 thrombocytopenia. He came off therapy and received palliative care before the trial was amended to add a signal inhibitor. RS4, RS5, and RS8 came off therapy due to PD. The detailed CLL prognostic factors, CLL therapy before transformation, RT-directed therapy before pembrolizumab, and biomarkers of RT patients are shown in Table 4.

Figure 1.

Changes in tumor burden, duration of therapy, and representative PET response in patients with RT receiving pembrolizumab. (A) The maximal percentage alteration in tumor burden from baseline in 9 RT patients. One patient (RS9), met the criteria for a PMR without having a 50% decrease in tumor burden but with a significant reduction of PET avidity. The color of each bar indicates whether a patient had prior ibrutinib therapy. (B) The response onset, and duration of therapy and DOR in RT patients. The length of the bar shows the time until the patient had a CR or a PR, along with the duration of the response and duration of therapy. Two patients (RS3 and RS7) who had SD, elected to discontinue the study in order to undergo alternative therapy. Three patients (RS1, RS2, and RS9) continued to receive pembrolizumab at the time of this report. Two patients (RS1 and RS2) had been added a signal inhibitor in addition to pembrolizumab (indicated by a blue arrow for the continuation phase) due to CLL progression in marrow (RS2) or a single locus RT progression detected on PET (RS1) (indicated by a solid red circle). RS1 had a DOR of 11 months for single-agent pembrolizumab and then received local radiation directed to one site of progression. He subsequently had a second CR and has maintained a CR with resumed pembrolizumab for 16 months of total therapy by the time of this report. RS2 had a DOR of 5 months for single-agent pembrolizumab and was then added idelalisib, and had pembrolizumab therapy for 12 months by the time of this report. RS6 had a DOR of ∼2 months before CLL marrow progression, leading to G3 thrombocytopenia. He came off therapy and received palliative care before the trial was amended to add a signal inhibitor. RS9 was in a sustained response of 3 months before the analysis cutoff. (C) The representative whole body PET images in RS2 at baseline prior to trial therapy and at the time point after 2 cycles of pembrolizumab treatment. The PET avid diseases were circled in these two PETs to compare the changes of PET-avid tumor. (D) The alteration of tumor burden and platelet count with the duration of therapy in RS2 during the single-agent therapy of pembrolizumab and the double-therapy of pembrolizumab with idelalisib. Arrow indicates the ongoing therapy. Trapezoid sign indicates a brief interruption of pembrolizumab due to thrombocytopenia.

Table 4.

Summary of clinical characteristics, best responses, and biomarker evaluation in RT patients

| RT patient | CLL biology and therapy | RT biology and therapy | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLL FISH | TP53 mut | IGHV | IGHV subset | CLL therapy prior to transformation and best response (DOR) | Prior RT therapy before Pembro and response (DOR) | % PD-1 | % PD-L1 | RT vs CLL clone | EBER | Best response to Pembro | Duration of Pembro therapy | |||

| RS1 | Normal | — | UM | 4-39*01 | PCR | CR (2 y) | RCHOP, RICE, RDHAP, Ibr | PD to chemo, PR to Ibr (5 mo), then PD | 52.3 | 17.4 | Rel | — | CR | 16 mo, ongoing |

| RS2 | del(17p) | — | UM | 3-30*03 | Ibr | PR-L (1.5 y) | None | 45.2 | 3.6 | Rel | — | PR | 12 mo, ongoing | |

| RS3 | del(13q) | + | UM | 4-39*01 | Ibr | PR (5 mo) | RCHOP | PR (3 mo), then PD | 22.8 | 1.6 | Rel | — | SD, skin lymphoma response | 2 mo, off therapy |

| RS4 | Normal | n/a | M | 4-1*02 | Untreated | REPOCH, Ibr | PD | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | SD, nodal reduction | 2 mo, off therapy | |

| RS5 | del(13q) | — | M | 1-18*01 | Untreated | RCHOP | PD | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | PD | 3 mo, off therapy | |

| RS6 | del(13q) | + | UM | 4-61*01 | Ibr | SD (6 mo) | None | 47.2 | 30.4 | n/a | — | PR | 4 mo, off therapy | |

| RS7 | del(17p) | — | UM | 1-2*02 | Untreated | RCHOP, auto-SCT |

CR (4.5 y), then PD | n/a | n/a | n/a | + | SD | 5 mo, off therapy | |

| RS8 | Normal | — | UM | 3-11*01 | Untreated | RCHOP, RICE, auto-SCT, RDHAP | CR (1 y), then PD | 1.0 | 4.0 | Rel | — | SD | 3 mo, off therapy | |

| RS9 | del(17p) | — | UM | 3-21*01 | Ibr | CR (2 y) | None | 21.4 | 34.0 | Rel | — | PMR | 3 mo, ongoing | |

Percent PD-1 and PD-L1 expression were quantitatively analyzed by calculating positive-cell percentage of the corresponding antigens in all cells of tumor samples. All 6 RT patients (RS1, RS2, RS3, RS6, RS8, and RS9) tested, did not have copy number gain nor amplification in chromosome 9p24. The RT disease of RS6 had PR to single-agent pembrolizumab for 4 months before he came off therapy due to thrombocytopenia caused by CLL marrow progression. RS3, RS4, RS5, RS7, and RS8 came off therapy due to lack of sufficient durable responses or alternative therapy.

auto-SCT, autologous stem cell transplant; EBER, Epstein-Barr virus–encoded RNA; Ibr, ibrutinib; M, mutated IGHV; n/a, not available; PCR, pentostatin, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab; Pembro, pembrolizumab; PR-L, PR with lymphocytosis; RCHOP, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; RDHAP, rituximab, cisplatin, cytarabine, and dexamethasone; Rel, clonally related between CLL and RT clones; REPOCH, rituximab, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone; RICE, rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide; TP53 mut, TP53 mutation; UM, unmutated IGHV.

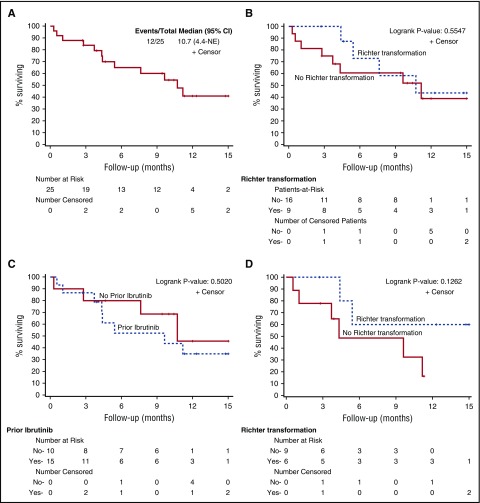

Survival

With a median follow-up of 10.4 (range, 2.7 to 16.1) months, the median OS for all patients was 10.7 months (95% CI, 4.4-not reached) (Figure 2A). To date, 11 patients (3 RT and 8 CLL) have progressed and 12 patients (4 RT and 8 CLL) have died. For RT and CLL patients, the median OS was 10.7 (95% CI, 4.4-not reached) and 11.2 (95% CI, 2.8-not reached) months, respectively (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

OS of patients in separate cohorts. (A-B) The OS of 25 patients in the entire cohort (A) and in a separate cohort of CLL (“no” to RT) vs RT (”yes” to RT) patients (B). (C) The OS of patients in 2 cohorts separated by having prior ibrutinib or no prior ibrutinib treatment. OS of patients who had prior ibrutinib treatment (n = 15) separated by CLL vs RT is shown in panel D. NE, not ended.

For patients who did or did not receive prior ibrutinib therapy, the median OS was 9.6 (95% CI, 3.7-not reached) and 10.7 (95% CI, 0.3-not reached) months, respectively (Figure 2C). Among 15 patients who had received prior ibrutinib therapy, the median OS for CLL and RT were 4.3 months (95% CI, 0.6-not reached) and not reached (95% CI, 4.4-not reached) (P = .13 by log-rank test) (Figure 2D). The median PFS for all, CLL, and RT patients were 3.0 (95% CI, 2.1-5.4), 2.4 (95% CI, 1.2-3.3), and 5.4 (95% CI, 2.8-12.2) months, respectively (supplemental Figure 2). PFS in RT patients is significantly longer than PFS in CLL patients (P = .013 by log-rank test).

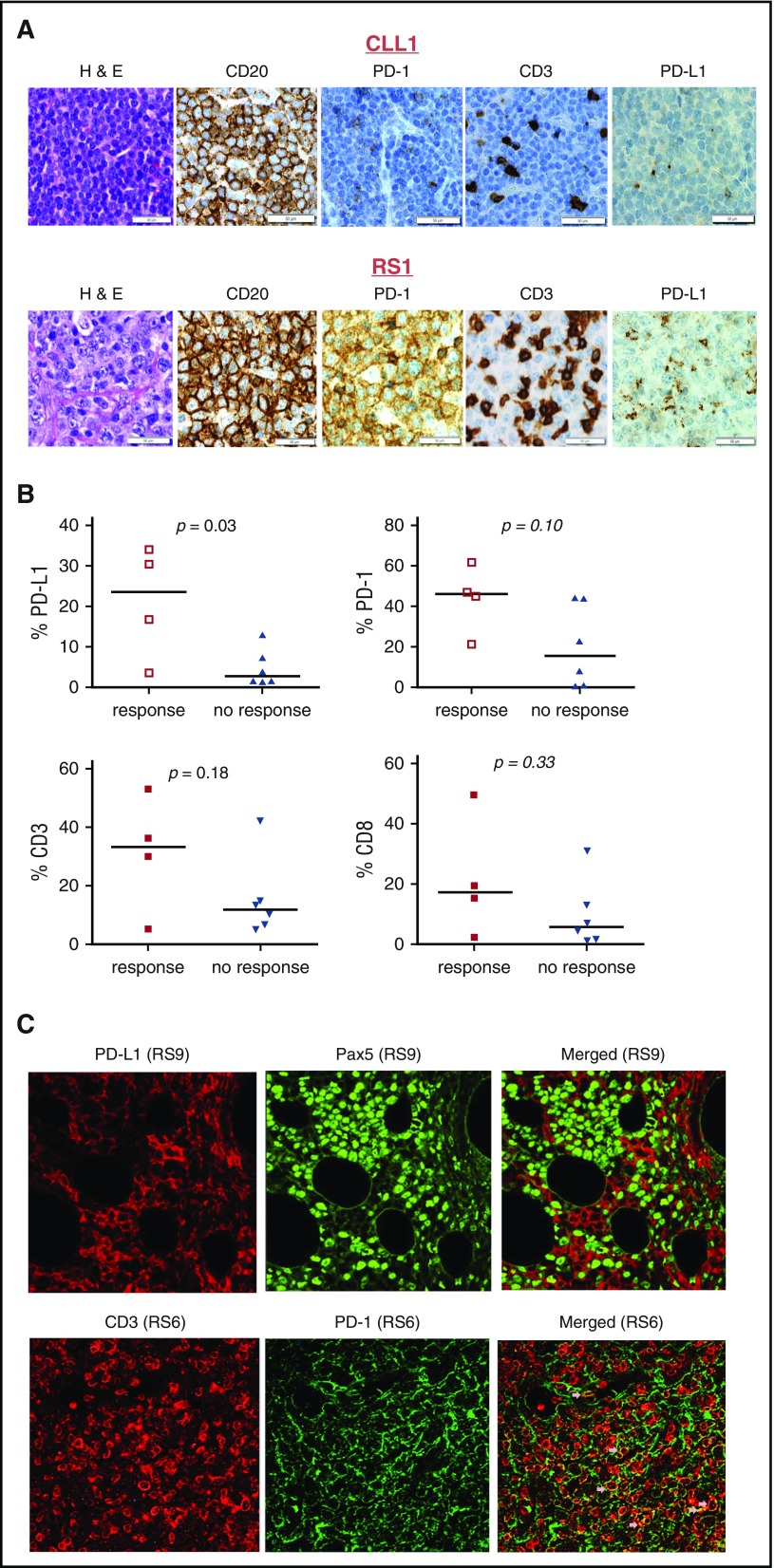

Biomarker assessment

A subgroup of 10 patients (6 RT and 4 CLL) had tumor-involved tissues (lymph node or skin biopsy) available at the baseline, underwent evaluation of PD-1, PD-L1, CD20, Pax5, CD3, and CD8 expression using IHC staining (Figure 3A). The percentage expression of each antigen was calculated by dividing the number of positive cells by the number of total cells scanned in the entire tissue area, and was independently validated by 2 hematopathologists (R.H. and A.L.F.). Increased expression of PD-L1 and an increased trend of expression of PD-1 (Figure 3B) were detected in the group of patients with confirmed response (CR/PR) in comparison with patients in the group without clinical response (PD or SD; P = .03 and P = .1 for PD-L1 and PD-1, respectively). Both CD3 and CD8 T-cell infiltrations appeared to be in similar levels in the responded and the without response group (P = .18 for CD3, P = .33 for CD8). In addition, double-color immunofluorescence analysis was performed to assess potential colocalization of CD3 with PD-1 and Pax5 with PD-L1 using confocal microscopy. A small percentage of PD-1 staining colocalized with CD3+ T cells (Figure 3C; supplemental Table 2). The majority of PD-1 staining was consistent with the leukemic/lymphoma B-cell staining pattern. PD-L1 staining was found to be mostly separated from Pax5-positive B cells and mostly stained cells, cytologically consistent with histiocytes (Figure 3C; supplemental Table 2). FISH analysis to assess the copy number of chromosome 9p24 showed none of the 9 tested samples had copy number gain or amplification for 9p24 (Table 4). Epstein-Barr virus staining was negative for most of tested cases (Table 4).

Figure 3.

Biomarker assessment of PD-1/PD-L1 expression and tumor-infiltrating T cells in treated patients. (A) The expression of PD-1, PD-L1, CD3, and CD20 detected by standard IHC in one representative RT- and one CLL-involved lymph node are shown in images taken using 40× visual field with magnification ×400. Scale bars = 50 μm. (B) The percentage of expression of PD-1, PD-L1, CD3, and CD8 in the baseline lymph nodes/tumors of 10 patients (6 RT and 4 CLL). PD-L1 expression is significantly increased (P = .03 by 2-tailed Student t test using 2-sample equal variance). PD-1 expression shows a trend for an increased level of expression (P = .10) in RT patients who have confirmed response in comparison with the CLL/RT patients who do not have confirmed responses. CD3 and CD8 expression are not different in these above 2 cohorts. Line represents median expression levels of individual antigens. Each open/filled square or triangle represents the % expression of individual antigen in 1 patient. (C) The representative images of PD-1 staining (green) in conjunction with CD3 (red) and PD-L1 expression (red) in conjunction with Pax 5 (green), tested in dual-color immunofluorescent staining using confocal microscopy. PD-L1 has minimal colocalization with Pax5-positive B cells (supplemental Table 2) and PD-L1–positive cells have the morphology of monocytic/histiocytic lineages. PD-1 partially colocalized with CD3, whereas the majority of PD-1 staining appears to be positive on tumor B cells (supplemental Table 2). Arrows point to the colocalization. Images were taken using 40× visual field with magnification ×400. H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

Five out of 9 (55%) RT patients were successfully generated genomic DNA from available tumor tissue and tested for a clonal relationship of the large cell lymphoma to CLL. All 5 patients had clonally related RT lymphoma to their underlying CLL (Table 4). Given the known association of DNA mismatch repair status with clinical response of colon cancer patients treated with pembrolizumab,37 we analyzed the mismatch repair status of the enrolled trial patients. Among 18 patients tested, only 1 had microsatellite instability high. The remaining patients had either microsatellite instability low (n = 6) or microsatellite stable (n = 11) status. There was no clear association of DNA mismatch repair status with clinical response of enrolled patients (supplemental Table 3). We also assessed the baseline peripheral blood CD3+, CD4+, CD8+, and naïve T-cell absolute numbers, and their percentage in lymphocytes. There were not significant differences between the patients with confirmed responses and the patients without responses (data not shown).

Discussion

In this phase 2 study, pembrolizumab had clinical activity in CLL patients with RT. In contrast, no clear activity was observed for patients with relapsed CLL. In heavily pretreated RT patients, the majority of whom had received prior anthracycline-containing chemotherapy and/or ibrutinib, pembrolizumab was associated with an ORR of 44% and an OS of ∼11 months. Clinically durable responses were observed in RT patients who experienced progression after prior ibrutinib. The majority of drug-related nonhematologic AEs were G1 or G2. Immune-related AEs (liver toxicities and pneumonitis) were observed in a small proportion of patients. The incidence of severe drug-related AEs was low. Drug-related hematologic G3 or G4 AEs occurred in ∼20% of patients. These results were similar to that in other trials of novel agents in relapsed CLL, but appeared to be less than the observed hematologic AEs in RT treated with chemotherapy (∼40% to 90% G3 or G4 hematologic AEs).4,39

In patients developing RT after receiving prior ibrutinib, 4 out of 6 patients (66%) had a confirmed clinical response and the median OS had not been reached at the time of this report after a median follow-up time of 11 months. These results compare extremely favorably to ibrutinib-treated CLL with RT in whom the median survival was 4 months after treatment using standard chemotherapy. Although the mutational profile of CLL patients with transformation to DLBCL is distinct from de novo DLBCL,27 the response rates to PD-1–blocking antibody appear to be similar among both groups of patients (30% to 40%), but the response to PD-1 blockade in RT patients appear to be more durable than that in de novo DLBCL. In a phase 1b study using nivolumab among patients with relapsed/refractory de novo DLBCL, ORR was 36% and PFS was only 7 weeks (which is shorter than 5.4 months observed in the current study).25 The clinical responses to pembrolizumab in CLL patients with transformation to DLBCL are especially encouraging, considering that most of these are clonally related to the underlying CLL and ∼70% have progressed on prior ibrutinib, both of which are associated with very poor response to salvage therapy and survival.

Among 16 relapsed CLL patients without RT, none had a confirmed response to pembrolizumab. Of note, the observed short survival in ibrutinib-treated CLL in the current study appear to be similar to published reports.5,6 Notably, among 3 RT patients who had PR to pembrolizumab, only the RT phase responded to pembrolizumab. The CLL component of their disease, particularly in the BM, continued to progress with worsening thrombocytopenia. The only CR response occurred in the RT patient who did not have CLL involvement in the BM at the time of trial enrollment. Because of these observations, we subsequently modified the clinical protocol to allow the addition of an approved CLL therapy in order to control underlying CLL when the RT was controlled. We have observed successful control of CLL in the BM of RT patients in selected cases (RS2). These clinical observations suggest the presence of significant biologic heterogeneity between CLL and large cell lymphoma clones in the same patient, even though the lymphoma was clonally related to the leukemic CLL B cells in these patients. The etiology for the differential responses of CLL vs RT disease to pembrolizumab is unclear and needs to be further investigated. One potential explanation maybe that the tumor-specific antigens in RT vs CLL are different and tumor-reactive T cells are only capable of recognizing RT-derived antigens to trigger cytotoxicity. For RT patients with co-existing CLL, combination therapy of PD-1 blockade with a CLL-directed therapy is likely needed to control both diseases.

Biomarker assessment performed on the available tumor tissues in CLL and RT patients showed increased PD-L1 expression and a trend for higher PD-1 staining among the RT patients with confirmed clinical responses. These results are similar to the finding of clinical trials using pembrolizumab in solid tumors,12 and indicate that PD-1/PD-L1 expression in the tumor and tumor microenvironment may be useful biomarkers for the selection of RT patients potentially responsive to PD-1 blockade. In addition, none of the tested tumor samples contain copy number gain or amplification in chromosome 9p24, which appear to be different from relapsed HL.13,40 Based on these results, our protocol was amended to add a focused RT cohort (cohort C), which is accruing patients. The limitations of this study include that this is a single-center study with a small sample size. Although the results among CLL patients with RT are promising, larger trials with longer follow-up will be necessary to confirm these findings in this subgroup of patients with dismal outcomes. In fact, the sponsor of the current study, Merck, has initiated an international study of single-agent pembrolizumab in CLL patients with RT (#NCT02576990).

In conclusion, results from this study demonstrate single-agent pembrolizumab selective activity in CLL patients with RT and an acceptable safety profile. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to show the benefit of PD-1 blockade in CLL patients with RT and led to additional studies of PD-1 blockade in this disease. These results could change the landscape of therapy for these patients, if further validated.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Merck & Co., Inc. (Kenilworth, NJ), Merck investigator-initiated study program, grants from the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute’s Lymphoma Specialized Programs of Research Excellence (CA 97274, K23 CA160345, and K12 CA090628), the Richard M. Schulze Family Foundation for Awards in Cancer Research, the Fraternal Order of Eagles Cancer Research Fund, and the Predolin Foundation.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: W.D. and S.M.A. are the study chair and co-chair for this trial; W.D., S.M.A., B.R.L., H.D., and J.L.-R. contributed to study design; W.D., B.R.L., T.G.C., S.A.P., J.F.L., R.H., T.D.S., S.S., J.L.-R., T.M.H., T.E.W., G.S.N., M.J.C., D.A.B., C.N.A., X.L., X.W., H.Z., C.R.S., S.T., L.E.W., E.B., I.M., and H.Y. contributed to data collection; W.D., S.M.A., B.R.L., J.L.-R., R.H., A.L.F., E.A., G.A.W., D.L.V.D., P.T.G., Y.L., D.S.V., A.A.C.-K., and H.D. contributed to data analyses and interpretation; B.R.L., E.A., S.M.A., S.A.P., T.D.S., and N.E.K. contributed to writing this report; W.D. wrote the manuscript; and all authors reviewed the report and approved the draft submission.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: W.D., T.D.S., and S.M.A. report research funding from Merck & Co., Inc. T.D.S., N.E.K., and S.A.P. report research funding from Pharmacyclics. T.D.S. reports research funding from Janssen, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, AbbVie, Celgene, and Hospira. S.M.A. reports research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Seattle Genetics, Celldex, and Affimed. N.E.K. reports research funding from Tolera and Acerta, and has been on the advisory board for Gilead, Morphosys, Infinity Pharm, and Celgene. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Wei Ding, Division of Hematology, Mayo Clinic, 200 First St SW, Rochester, MN 55905; e-mail: ding.wei@mayo.edu.

References

- 1.Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Three-year follow-up of treatment-naïve and previously treated patients with CLL and SLL receiving single-agent ibrutinib. Blood. 2015;125(16):2497-2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(1):32-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Furman RR, Sharman JP, Coutre SE, et al. Idelalisib and rituximab in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(11):997-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts AW, Davids MS, Pagel JM, et al. Targeting BCL2 with venetoclax in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):311-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maddocks KJ, Ruppert AS, Lozanski G, et al. Etiology of ibrutinib therapy discontinuation and outcomes in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(1):80-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain P, Keating M, Wierda W, et al. Outcomes of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia after discontinuing ibrutinib. Blood. 2015;125(13):2062-2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, et al. Safety and tumor responses with lambrolizumab (anti-PD-1) in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(2):134-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(26):2443-2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolchok JD, Kluger H, Callahan MK, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(2):122-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(2):123-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, et al. ; KEYNOTE-006 investigators. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2521-2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, et al. ; KEYNOTE-001 Investigators. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(21):2018-2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ansell SM, Lesokhin AM, Borrello I, et al. PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(4):311-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xerri L, Chetaille B, Serriari N, et al. Programmed death 1 is a marker of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma and B-cell small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia [published correction appears in Hum Pathol. 2010;41(11):1655]. Hum Pathol. 2008;39(7):1050-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grzywnowicz M, Zaleska J, Mertens D, et al. Programmed death-1 and its ligand are novel immunotolerant molecules expressed on leukemic B cells in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muenst S, Hoeller S, Willi N, Dirnhofera S, Tzankov A. Diagnostic and prognostic utility of PD-1 in B cell lymphomas. Dis Markers. 2010;29(1):47-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grzywnowicz M, Karabon L, Karczmarczyk A, et al. The function of a novel immunophenotype candidate molecule PD-1 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56(10):2908-2913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grzywnowicz M, Karczmarczyk A, Skorka K, et al. Expression of programmed death 1 ligand in different compartments of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Acta Haematol. 2015;134(4):255-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramsay AG, Clear AJ, Fatah R, Gribben JG. Multiple inhibitory ligands induce impaired T-cell immunologic synapse function in chronic lymphocytic leukemia that can be blocked with lenalidomide: establishing a reversible immune evasion mechanism in human cancer. Blood. 2012;120(7):1412-1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramsay AG, Evans R, Kiaii S, Svensson L, Hogg N, Gribben JG. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells induce defective LFA-1-directed T-cell motility by altering Rho GTPase signaling that is reversible with lenalidomide. Blood. 2013;121(14):2704-2714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramsay AG, Johnson AJ, Lee AM, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia T cells show impaired immunological synapse formation that can be reversed with an immunomodulating drug. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(7):2427-2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McClanahan F, Hanna B, Miller S, et al. PD-L1 checkpoint blockade prevents immune dysfunction and leukemia development in a mouse model of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2015;126(2):203-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McClanahan F, Riches JC, Miller S, et al. Mechanisms of PD-L1/PD-1-mediated CD8 T-cell dysfunction in the context of aging-related immune defects in the Eμ-TCL1 CLL mouse model. Blood. 2015;126(2):212-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armand P, Nagler A, Weller EA, et al. Disabling immune tolerance by programmed death-1 blockade with pidilizumab after autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results of an international phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(33):4199-4206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lesokhin AM, Ansell SM, Armand P, et al. Nivolumab in patients with relapsed or refractory hematologic malignancy: preliminary results of a phase Ib study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(23):2698-2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Westin JR, Chu F, Zhang M, et al. Safety and activity of PD1 blockade by pidilizumab in combination with rituximab in patients with relapsed follicular lymphoma: a single group, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(1):69-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fabbri G, Khiabanian H, Holmes AB, et al. Genetic lesions associated with chronic lymphocytic leukemia transformation to Richter syndrome. J Exp Med. 2013;210(11):2273-2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rossi D, Spina V, Deambrogi C, et al. The genetics of Richter syndrome reveals disease heterogeneity and predicts survival after transformation. Blood. 2011;117(12):3391-3401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015;348(6230):124-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, et al. ; International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood. 2008;111(12):5446-5456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(27):3059-3068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. ; International Harmonization Project on Lymphoma. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(5):579-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurtin PJ, Hobday KS, Ziesmer S, Caron BL. Demonstration of distinct antigenic profiles of small B-cell lymphomas by paraffin section immunohistochemistry. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999;112(3):319-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang KL, Chen YY, Shibata D, Weiss LM. Description of an in situ hybridization methodology for detection of Epstein-Barr virus RNA in paraffin-embedded tissues, with a survey of normal and neoplastic tissues. Diagn Mol Pathol. 1992;1(4):246-255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rossi D, Spina V, Cerri M, et al. Stereotyped B-cell receptor is an independent risk factor of chronic lymphocytic leukemia transformation to Richter syndrome. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(13):4415-4422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langerak AW, Groenen PJ, Brüggemann M, et al. EuroClonality/BIOMED-2 guidelines for interpretation and reporting of Ig/TCR clonality testing in suspected lymphoproliferations. Leukemia. 2012;26(10):2159-2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2509-2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nunes C, Wong R, Mason M, Fegan C, Man S, Pepper C. Expansion of a CD8(+)PD-1(+) replicative senescence phenotype in early stage CLL patients is associated with inverted CD4:CD8 ratios and disease progression [published correction appears in Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(13):3714]. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(3):678-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parikh SA, Kay NE, Shanafelt TD. How we treat Richter syndrome. Blood. 2014;123(11):1647-1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roemer MG, Advani RH, Ligon AH, et al. PD-L1 and PD-L2 genetic alterations define classical Hodgkin lymphoma and predict outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(23):2690-2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]