ABSTRACT

Cyclic AMP-responsive element binding protein, hepatocyte specific (CREBH), is a liver-enriched, endoplasmic reticulum-tethered transcription factor known to regulate the hepatic acute-phase response and lipid homeostasis. In this study, we demonstrate that CREBH functions as a circadian transcriptional regulator that plays major roles in maintaining glucose homeostasis. The proteolytic cleavage and posttranslational acetylation modification of CREBH are regulated by the circadian clock. Functionally, CREBH is required in order to maintain circadian homeostasis of hepatic glycogen storage and blood glucose levels. CREBH regulates the rhythmic expression of the genes encoding the rate-limiting enzymes for glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, including liver glycogen phosphorylase (PYGL), phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1 (PCK1), and the glucose-6-phosphatase catalytic subunit (G6PC). CREBH interacts with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) to synergize its transcriptional activities in hepatic gluconeogenesis. The acetylation of CREBH at lysine residue 294 controls CREBH-PPARα interaction and synergy in regulating hepatic glucose metabolism in mice. CREBH deficiency leads to reduced blood glucose levels but increases hepatic glycogen levels during the daytime or upon fasting. In summary, our studies revealed that CREBH functions as a key metabolic regulator that controls glucose homeostasis across the circadian cycle or under metabolic stress.

KEYWORDS: CREBH, circadian metabolism, gluconeogenesis, glucose metabolism, glycogenolysis, liver metabolism, nuclear receptor, transcriptional regulation

INTRODUCTION

In mammals, circadian rhythms orchestrate metabolic processes that are critical for health and disease. The liver is a major metabolic organ that plays primary roles in maintaining energy homeostasis across the circadian cycle (1, 2). In response to energy demands, the liver boosts metabolic pathways of energy utilization by breaking down glycogen, followed by gluconeogenesis (3). Glycogen breakdown is catalyzed by glycogen phosphorylase, liver form (PYGL), which cleaves glucose from the glycogen polymer and produces glucose-1-phosphate (4). PYGL is regulated through allosteric activation by AMP and via phosphorylation by protein kinase A (PKA), which is inhibited by insulin. Hepatic gluconeogenesis occurs during prolonged energy-demanding episodes and begins intramitochondrially with the induction of pyruvate carboxylase in the presence of an abundance of acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA). Gluconeogenesis is further regulated via allosteric and transcriptional activation of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PCK), fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase, and glucose-6-phosphatase, catalytic subunit (G6PC) (4). Additionally, when the glycogen in the liver is depleted, triglycerides in adipose tissue or the liver are catalyzed to fatty acids and glycerol. The fatty acids released are either oxidized as an energy source or metabolized to ketone bodies by the liver for energy supply to the brain, while glycerol is converted by the liver into glucose (3). Defects in these metabolic pathways may cause abnormal levels of glucose and lipids in the blood and the development of metabolic disorders.

Previous work has demonstrated the intimate and reciprocal interaction between the circadian clock system and fundamental metabolic pathways in the liver (1, 5). Dysregulation of circadian rhythms is closely associated with the development of human metabolic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, and obesity. Examination of nuclear receptor mRNA profiles in metabolic tissues has suggested that approximately half of the known nuclear receptors or transcriptional regulators exhibit rhythmic expression (6). We demonstrated recently that the liver-enriched, endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-tethered transcription factor CREBH (cyclic AMP-responsive element binding protein, hepatocyte specific) is regulated by the circadian clock and functions as a key regulator of circadian lipid metabolism (7–9). CREBH is activated through regulated intramembrane proteolysis (RIP), in which the CREBH precursor protein is transported from the ER to the Golgi complex, where it is cleaved by Site-1 and Site-2 proteases (8). We have demonstrated that proteolytic activation of CREBH protein is regulated by a circadian clock-regulated signaling pathway mediated through a BMAL1-AKT-glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) cascade (7). During the circadian cycle, the activated form of CREBH interacts with multiple metabolic transcriptional regulators to regulate the expression of genes encoding functions involved in both lipid utilization and storage in order to maintain energy homeostasis. Additionally, we determined that CREBH is a major regulator of the hepatic metabolic hormone FGF21 under the control of the circadian clock or upon fasting (7, 10). CREBH-null mice develop profound nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and hypertriglyceridemia when fed an atherogenic high-fat diet or after prolonged fasting (9, 11).

In this study, we demonstrate that CREBH plays an indispensable role in maintaining glucose homeostasis across the circadian cycle by regulating the expression of genes involved in glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis. CREBH interacts with the nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) to synergize its transcriptional activities in hepatic glucose metabolism. Dysfunction of CREBH in mice decreased blood glucose levels but increased hepatic glycogen storage levels under the control of the circadian clock or after fasting. These findings have important implications for the understanding of the molecular basis of circadian glucose metabolism and for the prevention and treatment of metabolic disorders.

RESULTS

CREBH is required in order to maintain rhythmic levels of blood glucose and hepatic glycogen across the circadian cycle.

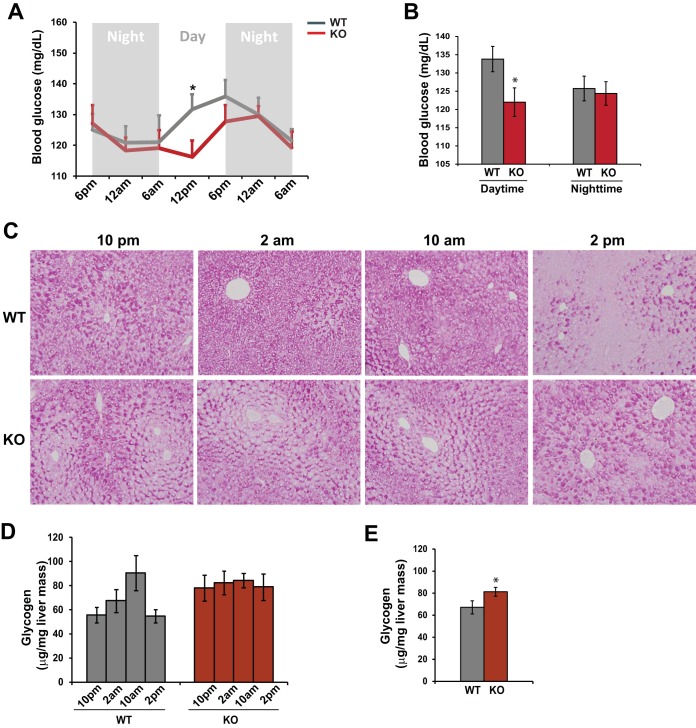

We recently revealed that CREBH is a circadian-clock-controlled regulator of lipid metabolism (7). CREBH has also been shown to regulate fasting-induced gluconeogenesis (12). Accordingly, we asked whether CREBH regulates glucose homeostasis across the circadian cycle. To address this question, we measured blood glucose levels of CREBH-null (knockout [KO]) and wild-type (WT) control mice at different points on the circadian clock. CREBH-null mice exhibited a phase-shifted rhythmic pattern of serum glucose levels (Fig. 1A). The blood glucose levels in CREBH-null mice were significantly lower than those in control mice during the daytime (6 a.m. to 6 p.m.) (Fig. 1A and B). Further, we examined the hepatic glycogen levels of CREBH-null and WT mice at representative time points in the circadian cycle. Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining of hepatic glycogen in CREBH-null and WT control mice at these representative time points indicated that the production of hepatic glycogen in WT mice exhibited a circadian rhythmic pattern: it was increased from 10 p.m. to 10 a.m. and was depleted at 2 p.m. (Fig. 1C). In contrast, hepatic glycogen storage in CREBH-null mice lost its rhythmic pattern: the distribution and levels of glycogen in the livers of CREBH-null mice exhibited discernible changes over the circadian period. This observation was confirmed by a quantitative enzymatic assay of hepatic glycogen levels (Fig. 1D). The enzymatic assay also showed that the average hepatic glycogen level in CREBH-null mice across the circadian cycle was significantly higher than that in WT mice (Fig. 1E). Taken together, these phenotypes suggest that CREBH is required in order to maintain glucose homeostasis by controlling rhythmic blood glucose levels and hepatic glycogen storage according to the circadian clock.

FIG 1.

CREBH regulates rhythmic levels of blood glucose and hepatic glycogen storage in mice under the control of the circadian clock. (A) Levels of blood glucose in CREBH-null and WT control mice across the circadian cycle. Blood glucose levels were measured every 6 h for 36 h in constant darkness. Data are presented as means ± standard errors of the means (n, 8 mice per time point) at each time point. *, P ≤ 0.05. (B) Average blood glucose levels in CREBH-null and WT control mice during the daytime or nighttime. Bars, means; error bars, standard errors of the means (n, 16 mice per group). (C) PAS staining reveals hepatic glycogen levels in CREBH-null and WT control mice at 10 p.m., 2 a.m., 10 a.m., and 2 p.m. (magnification, ×200). (D) Quantitative enzymatic analysis of hepatic glycogen levels in CREBH-null and WT control mice at 10 p.m., 2 a.m., 10 a.m., and 2 p.m. Bars, means; error bars, standard errors of the means (n, 3 mice per group per time point). (E) Quantitative enzymatic analysis of glycogen levels in pooled liver tissue samples collected from 12 CREBH-null or 12 WT control mice across the circadian cycle. Bars, means; error bars, standard errors of the means (n, 12 mice per group per time point).

CREBH promotes hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis.

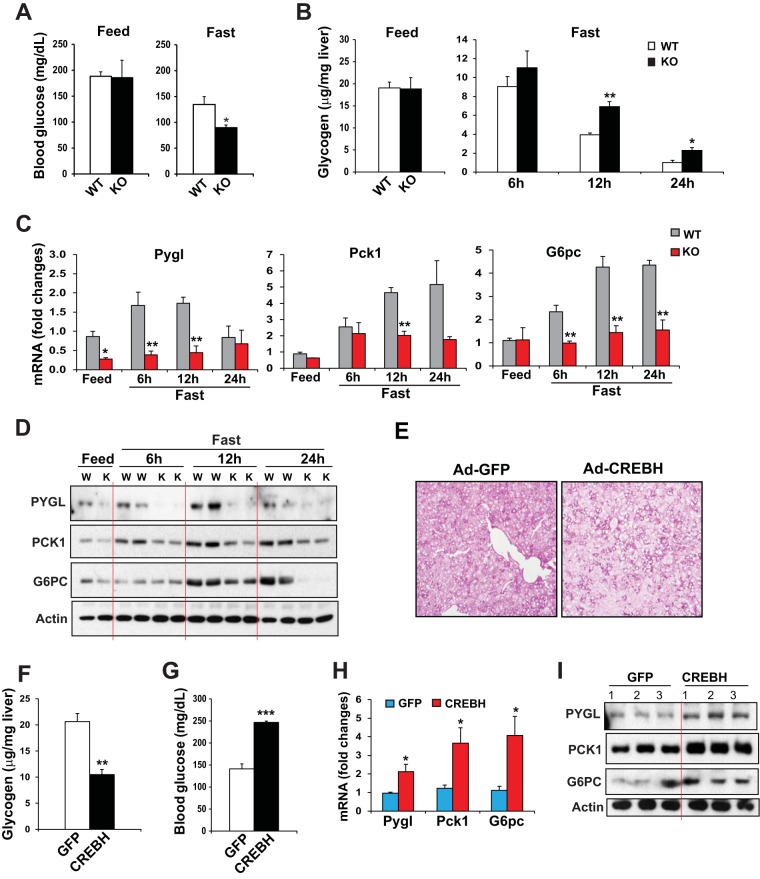

To determine the roles of CREBH in maintaining blood homeostasis, we challenged CREBH-null and WT control mice by fasting or by overexpression of the activated form of CREBH in their livers. After a 12-h fast, CREBH-null mice displayed significantly lower blood glucose levels but higher hepatic glycogen levels than WT control mice (Fig. 2A and B). This profile suggests that CREBH may be involved in regulatory pathways in hepatic glucose production and glycogen mobilization. To define the regulatory mechanism for CREBH as a transcription factor involved in maintaining glucose homeostasis, we examined the expression of genes encoding functions involved in glucose metabolic pathways, particularly gluconeogenesis, glycolysis, glycogen synthesis, and glycogenolysis, in the livers of CREBH-null and WT mice under feeding or fasting conditions. Among others, expression levels of the mRNAs encoding the rate-limiting enzyme in hepatic glycogenolysis, PYGL (4), and the key enzymes in gluconeogenesis, including PCK1 and G6PC (13), were significantly lower in the livers of CREBH-null mice at 6, 12, or 24 h after fasting than in those of WT control mice (Fig. 2C). Western blot analyses confirmed the reduced expression of the PYGL, PCK1, and G6PC proteins in the livers of CREBH-null mice upon fasting. As shown in Fig. 2D, the levels of PYGL protein in the livers of WT mice were gradually increased in response to fasting for 6 or 12 h but declined after a prolonged, 24-h fast. In contrast, the levels of PYGL in the livers of CREBH-null mice were diminished under feeding conditions or upon fasting (Fig. 2D; see also Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). Further, the levels of PCK1 in the livers of CREBH-null mice were significantly lower than those in WT mice under fasting conditions. With regard to G6PC, protein levels were increased in the livers of WT mice in a time-dependent manner. However, the levels of G6PC proteins in the livers of CREBH-null mice were significantly lower than those in WT mice at 12 h after fasting (Fig. 2D; also Fig. S1A). These data suggested that CREBH activates the expression of PYGL, PCK1, and G6PC in the liver upon fasting and therefore that CREBH may regulate hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis in response to energy demands.

FIG 2.

CREBH promotes hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis upon fasting or CREBH overexpression. (A) Levels of blood glucose in CREBH-null and WT control mice under feeding conditions or after a 12-h fast. Bars, means; error bars, standard errors of the means (n, 3 mice per time point). *, P < 0.05. (B) Hepatic glycogen levels in CREBH-null and WT control mice under feeding conditions or after fasting for 6, 12, or 24 h. Bars, means; error bars, standard errors of the means (n, 3 mice per time point). **, P < 0.01. (C) Expression levels of Pygl, Pck1, and G6pc mRNAs in the livers of CREBH-null and WT control mice under feeding conditions or after fasting for 6, 12, or 24 h. mRNA expression levels were determined by qRT-PCR. Fold changes in mRNA levels were determined by comparison to the mRNA levels in one of the wild-type control mice under the feeding condition. Bars, means; error bars, standard errors of the means (n, 3 or 4 mice per time point). (D) Western blot analysis of PYGL, PCK1, and G6PC proteins in mouse livers under feeding conditions or after a 6-, 12-, or 24-h fast. (E) PAS staining of glycogen in the livers of mice overexpressing GFP or activated CREBH (magnification, ×200). WT mice were injected through the tail vein with a recombinant adenovirus (Ad) expressing activated CREBH or GFP as a control. At 3 days after the injection, the animals were euthanized for the examination of hepatic glycogen and blood glucose. (F and G) Levels of hepatic glycogen (F) and blood glucose (G) in mice overexpressing GFP or activated CREBH in the liver. Bars, means; error bars, standard errors of the means (n, 3 mice). ***, P < 0.001. (H) Expression levels of Pygl, Pck1, and G6pc mRNAs in the livers of mice overexpressing GFP or activated CREBH. mRNA expression levels were determined by qRT-PCR. Fold changes in mRNA levels were determined by comparison to the mRNA levels in one of the mice overexpressing GFP. Bars, means; error bars, standard errors of the means (n, 3 mice). (I) Western blot analysis of PYGL, PCK1, and G6PC proteins in the livers of mice overexpressing GFP or activated CREBH. Levels of β-actin were determined as loading controls.

Additionally, we examined the expression of other major glycogen metabolism-related enzymes, including glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β), UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase 1 (UGP1), phosphorylase kinase regulatory subunit alpha 2 (PHKA2), glycogen branching enzyme (GBE), and glycogen debranching enzyme (AGL), in the livers of CREBH KO and WT control mice upon fasting. While the expression levels of the Gsk3β, Ugp1, Gbe, and Agl mRNAs in the livers of CREBH KO mice were comparable to those in WT mice, the expression levels of the mRNA encoding PHKA2, the key regulatory unit of glycogen phosphorylase kinase, were significantly reduced in the livers of CREBH KO mice upon fasting (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). This is consistent with the role of CREBH in promoting glycogen metabolism (glycogenolysis) through the facilitation of liver glycogen phosphorylase (PYGL) activity.

Next, to validate the functions of CREBH in promoting glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, we expressed the activated form of CREBH in the livers of mice by use of an adenovirus-based overexpression system. Upon overexpression of the activated CREBH protein in mouse livers, hepatic glycogen levels were significantly decreased, as revealed by both PAS staining for hepatic glycogen storage (Fig. 2E) and the enzymatic assay of hepatic glycogen levels (Fig. 2F). Further, blood glucose levels in mice with livers overexpressing the activated form of CREBH were significantly higher than those in mice overexpressing the control, green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Fig. 2G). Confirming the roles of CREBH in driving PYGL, PCK1, and G6PC expression in the liver, both mRNA and protein levels for PYGL, PCK1, and G6PC in the livers of mice overexpressing the activated form of CREBH were significantly higher than those for mice overexpressing the control, GFP (Fig. 2H and I; also Fig. S1B in the supplemental material). Taken together, these results indicated that CREBH promotes hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis by activating the expression of the rate-limiting enzymes in these two metabolic pathways.

CREBH functions as a rhythmic transcriptional activator of the key genes involved in glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis under the control of the circadian clock.

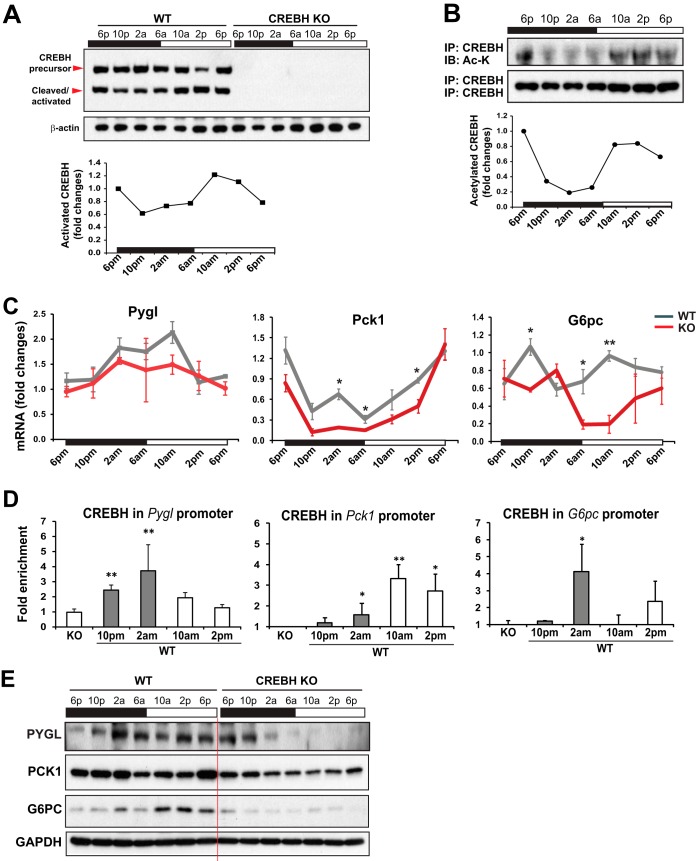

To understand the molecular basis underlying the role of CREBH in regulating circadian glucose homeostasis, we examined the circadian rhythmic activation of CREBH and the expression of the key genes encoding functions involved in hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis. Supporting clock-controlled proteolytic activation of CREBH (7), Western blot analysis with membrane and nuclear protein fractions prepared from pooled liver tissues of mice across the circadian cycle showed that production of the cleaved/activated CREBH protein exhibited typical rhythmicity (Fig. 3A). Previously, we demonstrated that a regulatory CREBH posttranslational modification process, lysine-specific acetylation, plays a critical role in CREBH transcriptional activities (14). We therefore examined CREBH lysine acetylation in the livers of mice across the circadian cycle. Immunoprecipitation (IP) and Western blot analysis revealed that acetylation of CREBH in mouse livers displayed a typical circadian rhythmicity (Fig. 3B), in which the levels of acetylated CREBH reached a trough at 2 a.m. and peaked during the daytime from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., when the metabolic pathways for energy supplies are elevated in mice. Apparently, the elevation of CREBH acetylation coincided with the increase in levels of the cleaved CREBH protein, suggesting that CREBH activity is regulated by the circadian clock and correlates with energy demands during the daytime in mice.

FIG 3.

CREBH regulates rhythmic expression of the key genes involved in hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis in mice under the control of the circadian clock. (A) (Top) Western blot analysis of levels of CREBH precursor and activated/cleaved forms in mouse livers over the circadian cycle. Liver tissues were collected from WT or KO mice every 4 h over a 24-h circadian cycle (n, 3 mice/genotype/time point). Tissues from each group at each time point were pooled, and cellular proteins were prepared from the pooled tissues. Levels of β-actin protein were determined as controls. (Bottom) Graph showing the quantification of activated/cleaved CREBH protein in mouse livers over the circadian cycle. The intensity of the CREBH protein signal, determined by Western blot densitometry, was normalized to that of β-actin. Fold changes in protein levels were determined by comparison to the protein level at 6 p.m. (B) (Top) IP-Western blot analysis of levels of acetylated CREBH protein in mouse livers over the circadian cycle. Nuclear proteins from pooled liver tissues of WT mice over a 24-h circadian cycle (n, 3 mice/time point) were immunoprecipitated with the anti-CREBH antibody to pull down the CREBH protein complex, followed by immunoblotting (IB) with the anti-acetyl-lysine antibody. The levels of CREBH protein pulled down were determined as the controls. (Bottom) Graph showing the quantification of acetylated CREBH protein in mouse livers over the circadian cycle. The intensity of the lysine-acetylated CREBH protein signal, determined by Western blot densitometry, was normalized to that of CREBH. Fold changes in protein levels were determined by comparison to the starting level at 6 p.m. (C) Rhythmic expression levels of Pygl, Pck1, and G6pc in the livers of CREBH-null and WT control mice. mRNA expression levels were determined by qRT-PCR. Fold changes in mRNA levels were determined by comparison to levels in one of the wild-type control mice at the starting circadian time point. Bars, means; error bars, standard errors of the means (n, 3 to 5 mice per group per time point). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. (D) CREBH enrichment in the Pygl, Pck1, and G6pc gene promoters in the livers of WT mice at different circadian phases, as determined by ChIP-qPCR. CREBH-null liver nuclei were used as negative controls for the endogenous CREBH ChIP assays. CREBH enrichment in the gene promoters at different circadian phases was quantified by comparing ChIP-qPCR signals from the samples pulled down by the anti-CREBH antibody to that pulled down by a rabbit anti-IgG antibody. Bars, means; error bars, standard errors of the means (n, 3 mice per time point). (E) Western blot analysis of rhythmic levels of PYGL, PCK1, and G6PC proteins in the livers of CREBH-null and WT mice, collected every 4 h in a 24-h circadian period. Pooled liver protein lysates from 3 to 5 mice per time point per genotype group were used.

Next, we examined the expression of the rate-limiting enzymes in hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, including PYGL, PCK1, and G6PC, in the livers of CREBH-null and WT control mice over the circadian cycle. The expression levels of Pygl mRNA were lower in the livers of CREBH-null mice than in those of WT mice from 2 a.m. to 2 p.m. (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, the expression levels of Pck1 and G6pc mRNAs were also decreased in the livers of CREBH-null mice during the resting phases of the circadian cycle (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that CREBH regulates circadian rhythmic expression of the key regulators or enzymes in hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, both of which contribute to maintaining blood glucose levels upon energy demands. Additionally, we examined the rhythmic expression of the key enzyme in glycogen synthase, glycogen synthase 2 (GYS2), in the livers of CREBH KO and WT control mice. The expression of Gys2 mRNA in the livers of CREBH KO mice exhibited a circadian rhythm reversed from that in the livers of WT mice during the 24-h day-night cycle (see Fig. S3A in the supplemental material). However, Western blot analysis showed that levels of GYS2 protein in the livers of CREBH KO mice were comparable to those in the livers of WT control mice over the circadian clock (Fig. S3B), suggesting that GYS2 is not a direct target enzyme through which CREBH regulates glycogen metabolism.

The promoter regions of the Pygl, Pck1, and G6pc genes contain typical CRE-binding motifs (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). To evaluate whether CREBH, as a transcriptional activator, can directly target the Pygl, Pck1, and G6pc gene promoters over the circadian cycle, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis to quantify the enrichment of CREBH in the promoter regions of these genes in mouse liver tissues collected at different circadian phases. ChIP-qPCR analyses indicated that enrichment of CREBH at the Pygl gene promoter was increased during the time from 10 p.m. to 10 a.m. (Fig. 3D). In the Pck1 and G6pc gene promoters, enrichment of CREBH peaked at 10 a.m. and 2 a.m., respectively. The profiles of CREBH enrichment at the Pygl, Pck1, and G6pc gene promoters were consistent with their mRNA expression profiles and the time when gluconeogenesis is elevated in mice (Fig. 3C and D). To confirm the requirement of CREBH for circadian-rhythm-regulated production of the PYGL, PCK1, and G6PC proteins, we performed Western blot analyses with liver tissues from CREBH-null and WT control mice over the circadian cycle. Levels of PYGL, PCK1, and G6PC proteins in the livers of CREBH-null mice were lower than those in the livers of WT mice (Fig. 3E; see also Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). These results indicate that CREBH activates the expression of PYGL, PCK1, and G6PC and thus regulates hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis in mice during the circadian cycle. However, it should be noted that the temporal kinetics of CREBH cleavage/acetylation, CREBH enrichment at the target gene promoters, and expression of the Pygl, Pck1, and G6pc transcripts are quite different across the circadian cycle (Fig. 3A to C). In addition to the circadian regulation, the transcription of the Pygl, Pck1, and G6pc genes is differentially regulated by a variety of transcription activators or repressors triggered by diverse metabolic or hormonal signals. Due to alternative transcriptional regulation, the presence of activated CREBH does not necessarily coincide with CREBH enrichment at the Pygl, Pck1, or G6pc gene promoter or with transcription of the gene—an interesting issue to be investigated in the future.

Acetylation of CREBH regulates CREBH-PPARα interaction and synergy in promoting hepatic glucose metabolism.

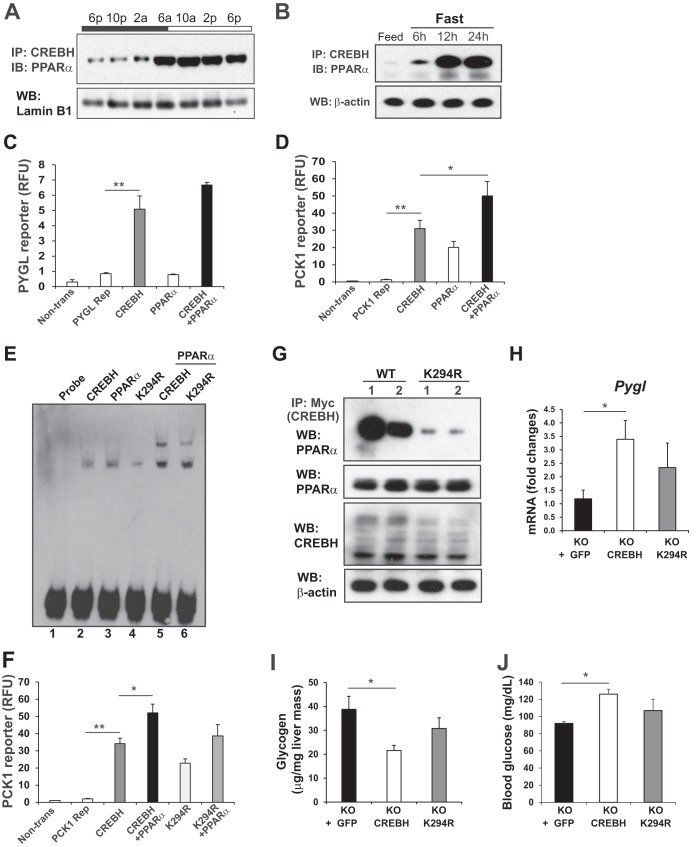

The activation and function of circadian transcriptional regulators are regulated through intimate and reciprocal interactions with other transcriptional factors or nuclear receptors (1, 15). PPARα is a liver-enriched, clock-regulated nuclear receptor that plays key roles in regulating lipid and glucose metabolism during the starvation phase (16). We demonstrated previously that CREBH interacts with PPARα to synergistically activate expression of the gene encoding the metabolic hormone FGF21 (10). We investigated whether CREBH rhythmically interacts with PPARα in the livers of mice over the circadian cycle. IP and Western blot analyses with mouse livers collected across the day-night cycle indicated that CREBH interacts with PPARα during the daytime/starvation circadian phases (Fig. 4A), a period when glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis, and lipid mobilization are sequentially activated in mice in response to energy demands. Consistently, CREBH interacts with PPARα in a time-dependent manner in mouse livers in response to fasting (Fig. 4B). Notably, dramatic increases in CREBH-PPARα interaction were observed in the livers of mice after relatively long (12- and 24-h), but not short (6-h), periods of fasting.

FIG 4.

Lysine acetylation of CREBH regulates CREBH-PPARα interaction and synergy in regulating hepatic glucose metabolism. (A) IP and Western blot analysis of interactions between CREBH and PPARα in the liver nuclear fractions of WT mice over a 24-h circadian period. Liver nuclear proteins pooled from 3 WT mice per time point were pulled down by the anti-CREBH antibody and were then probed with the PPARα antibody. Levels of lamin B1 were determined as controls. (B) IP and Western blot analysis of interactions between CREBH and PPARα in the livers of mice after a 6-, 12-, or 24-h fast. Total liver cellular lysates were used for Western blot analysis. Levels of β-actin were determined as controls. (C and D) Luciferase reporter (Rep) analyses of transcriptional activation of the human Pygl (C) or Pck1 (D) gene promoter by CREBH alone or in combination with PPARα. Hepa1-6 cells were transduced with the reporter vector or a vehicle. After 24 h, the transfected cells were infected with an adenovirus expressing GFP (control), CREBH, and/or PPARα. A Renilla reporter plasmid was included in the cotransfection for the normalization of luciferase reporter activities. The same adenovirus titers were used for individual infections. Bars, means; error bars, standard errors of the means (n, 2 experimental repeats). Non-trans, nontransfected cell control. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. (E) Binding of cellular extracts from Hepa1-6 cells expressing GFP, CREBH, or PPARα to the mouse PCK1 gene promoter oligonucleotide. EMSA was performed using extracts from Hepa1-6 cells infected with an adenovirus expressing GFP, CREBH, the K294R mutant, and/or PPARα and the PCK1 gene probe containing the CREBH-PPAR binding motif. The formation of a CREBH-DNA or PPARα-DNA complex is indicated by a shifted band, and the formation of a CREBH-PPARα-DNA complex is indicated by a supershifted band. “Probe” indicates the control reaction with the CREBH-PPAR probe in the absence of cellular extracts. (F) Luciferase reporter analyses of transcriptional activation of the mouse Pck1 gene promoter by CREBH or the K294R mutant alone or in combination with PPARα. A Renilla reporter plasmid was included in the cotransfection for the normalization of luciferase reporter activities. Bars, means; error bars, standard errors of the means (n, 2 experimental repeats). (G) IP and Western blot analysis of interactions between PPARα and CREBH or the K294R mutant in the livers of mice under fasting conditions. A recombinant adenovirus expressing either GFP as a control, Myc-tagged full-length human CREBH protein (WT), or the acetylation-deficient mutant (K294R) was injected into the tail veins of CREBH-null mice. (Top panel) Liver protein lysates collected from the mice after a 24-h fast were immunoprecipitated with the Myc antibody to pull down the CREBH protein complex, followed by immunoblotting with the PPARα antibody. (Lower panels) Western blot analyses to determine the levels of PPARα, Myc-tagged CREBH, and β-actin. (H) Expression levels of Pygl mRNA in the livers of CREBH-null mice expressing GFP, WT CREBH, or the K294R mutant after fasting as described in the legend to panel G. mRNA expression levels were determined by qRT-PCR. Bars, means; error bars, standard errors of the means (n, 3 mice per group). (I and J) Levels of hepatic glycogen (I) and blood glucose (J) in mice overexpressing GFP, WT CREBH, or the K294R mutant in their livers. KO mice were injected through the tail vein with a recombinant adenovirus expressing GFP, WT CREBH, or the K294R mutant. At 3 days after the injection, the animals were fasted for 24 h before being euthanized for the examination of blood glucose and hepatic glycogen levels. Bars, means; error bars, standard errors of the means (n, 3 mice per time point).

To explore the functional significance of the interaction between CREBH and PPARα in glucose metabolism, we performed reporter analysis with the Pygl or Pck1 gene promoter. Indeed, the promoter region of the mouse Pygl gene possesses multiple CREBH-binding motifs, and the Pck1 gene possesses multiple binding motifs for CREBH and PPARα (Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). While overexpression of the active form of CREBH alone can significantly increase Pygl gene promoter activity, coexpression of CREBH with PPARα only insignificantly augmented the reporter activity (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, overexpression of CREBH alone significantly increased the expression of the Pck1 gene reporter (Fig. 4D). Coexpression of CREBH with PPARα increased Pck1 reporter expression to a greater extent than expression of either CREBH or PPARα alone. These results suggest that CREBH and PPARα function synergistically to drive the transcription of the Pck1 gene. However, CREBH-PPARα interaction has little synergy in driving the expression of the Pygl gene, the key gene in glycogenolysis.

Previously, we demonstrated that acetylation of CREBH at the lysine residue K294 is critical for CREBH-PPARα interaction and optimized CREBH transcriptional activity in lipid metabolism in response to fasting (14). As shown in Fig. 3B, lysine acetylation of CREBH was regulated by the circadian clock, with elevated levels during the daytime phases. To determine whether acetylation of CREBH at K294 can affect CREBH transcriptional activity in regulating glucose metabolism, we performed electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) with a mouse Pck1 gene promoter oligonucleotide containing both CREBH- and PPARα-binding motifs (Fig. S4 in the supplemental material) and cellular extracts from Hepa1-6 cells expressing CREBH, PPARα, or the K294R CREBH acetylation mutant. Binding to the Pck1 promoter oligonucleotide was detected with liver extracts from mice expressing CREBH or PPARα (Fig. 4E, lanes 2 and 3). However, the level of binding of liver extracts expressing CREBH K294R to the Pck1 promoter was significantly lower than that of liver extracts expressing WT CREBH or PPARα (Fig. 4E, lane 4). Further, when CREBH and PPARα were coexpressed, shifted binding signals that reflected the binding activities of heterodimerized CREBH and PPARα were detected (Fig. 4E, lane 5). In comparison, the shifted binding signals of liver extracts coexpressing CREBH K294R and PPARα were weaker than those of extracts coexpressing WT CREBH and PPARα (Fig. 4E, lane 6). These results suggested that CREBH and PPARα interact and bind to the Pck1 gene promoter and that CREBH acetylation at K294 is critical for the binding of CREBH-PPARα heterodimers to the Pck1 gene promoter. In agreement with the EMSA result, reporter analysis with the Pck1 gene promoter showed that the CREBH acetylation mutation at K294 (K294R) significantly decreased CREBH trans-activation activity as well as the synergy between CREBH and PPARα in driving the transcription of the Pck1 gene (Fig. 4F).

Next, to evaluate the impact of CREBH acetylation on hepatic glucose metabolism in vivo, we expressed Myc-tagged wild-type CREBH or the K294R mutant in CREBH-null mouse livers by use of an adenovirus-based delivery system. After a 24-h fast, a strong interaction between CREBH and PPARα was detected in mouse livers expressing wild-type CREBH (Fig. 4G). In contrast, the fasting-induced interaction between CREBH and PPARα in the liver was significantly repressed by the mutation at the acetylation residue K294, thus confirming the requirement of CREBH acetylation for fasting-induced CREBH-PPARα interaction in vivo. Further, we examined blood glucose and hepatic glycogen levels in CREBH-null mice infected with an adenovirus overexpressing GFP, CREBH, or the K294R mutant. Supporting the role of CREBH in promoting glycogenolysis, overexpression of activated CREBH in the livers of CREBH-null mice increased the expression of the Pygl gene, but decreased hepatic glycogen levels, relative to those observed upon overexpression of GFP in CREBH-null livers (Fig. 4H and I). However, overexpression of the K294R mutant failed to significantly decrease hepatic glycogen levels or increase expression of the Pygl gene in mouse livers. Moreover, overexpression of activated CREBH but not its K294R acetylation mutant increased blood glucose levels in mice (Fig. 4J). Together, these data confirmed the importance of CREBH acetylation at K294 in CREBH-driven hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis.

DISCUSSION

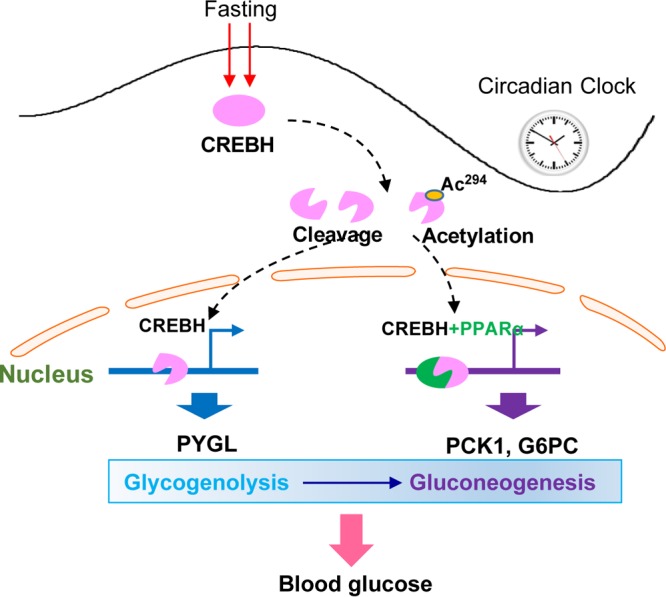

In this study, we demonstrated that CREBH is required in order to maintain circadian glucose homeostasis by regulating hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis. CREBH deficiency leads to reduced blood glucose levels and increased hepatic glycogen storage in mice during the daytime circadian phases or upon fasting. Specifically, our major findings include the following (Fig. 5): (i) the proteolytic cleavage and posttranslational acetylation modification of CREBH are regulated by the circadian clock; (ii) CREBH regulates hepatic glycogenolysis by activating PYGL expression during the daytime circadian phases or in response to fasting; (iii) CREBH regulates hepatic gluconeogenesis by activating the expression of PCK1 and G6PC during the daytime phases or after fasting; (iv) CREBH and PPARα act in synergy to regulate hepatic gluconeogenesis; and (v) acetylation of CREBH at K294 is critical for CREBH activity in regulating hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis. These findings demonstrate that CREBH is a major circadian transcriptional regulator for hepatic glucose metabolism. The functional activity of CREBH as a liver circadian metabolic regulator has a significant impact in maintaining glucose homeostasis and preventing the development of metabolic diseases.

FIG 5.

Working model of CREBH as a circadian metabolic regulator of hepatic glucose metabolism over the circadian cycle or under fasting conditions. Ac294, CREBH acetylation at lysine (K) 294.

In order to maintain blood glucose levels under conditions of metabolic need, the liver plays a major role in facilitating carbohydrate metabolism, which undergoes a shift from glucose storage during feeding toward glucose production via glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis during fasting (3, 4). These metabolic changes are reflected in the expression and/or activity of rate-limiting enzymes in hepatic metabolism. Conditions of energy demand, such as fasting or the starvation phases of the circadian cycle, stimulate the expression of the genes encoding the key enzymes in gluconeogenesis, including PCK1 and G6PC. Prior to gluconeogenesis, the expression of PYGL, the rate-limiting enzyme for glycogenolysis, is induced during early hours of fasting. Despite the importance of PYGL in glucose metabolism, the regulation of PYGL expression has not been fully investigated in the literature. Our work identified CREBH as a major transcriptional regulator of PYGL expression in the liver in response to energy demands. This is an important contribution to the understanding of the transcriptional regulation of glycogenolysis. Further, upon fasting or during the starvation phase of the circadian cycle, CREBH also regulates the expression of PCK1 and G6PC for hepatic gluconeogenesis. In this scenario, an interesting question is how CREBH switches its transcriptional activity from activating PYGL expression for glycogenolysis to activating PCK1 and G6PC expression for gluconeogenesis. The findings of CREBH-PPARα interaction and the synergy of CREBH and PPARα in driving the transcription of the Pck1 gene shed new light on the shift of CREBH activity in regulating hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis. Our study demonstrated that a significant increase in the CREBH-PPARα interaction was detected in mouse livers after relatively long (12- and 24-h), but not short (6-h), periods of fasting (Fig. 4B). CREBH and PPARα act in synergy to activate the expression of the Pck1 gene but not the Pygl gene (Fig. 4C and D). These findings are in line with the sequential activation of glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis during fasting. CREBH may achieve functional specificity in regulating hepatic glucose metabolic pathways through the interaction and synergy with PPARα.

In this study, we demonstrate that lysine acetylation of CREBH is an important regulatory event for CREBH activity in regulating hepatic glucose homeostasis. The activated form of CREBH protein is modified by lysine acetylation in mouse livers in a circadian-rhythm-dependent manner (Fig. 3B). Lysine acetylation of CREBH in mouse livers occurs mainly during the daytime or starvation circadian period. Importantly, the rhythmic pattern of CREBH acetylation coincided with the transcriptional activity of CREBH in regulating hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis under the control of the circadian clock or upon fasting (Fig. 1). Previously, we demonstrated that CREBH acetylation at lysine residue 294 is required for optimal CREBH-PPARα interaction and CREBH transcriptional activity in regulating lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation in the liver upon fasting (14). Similarly, lysine acetylation of CREBH is critical for CREBH transcriptional activity in regulating the expression of PYGL for glycogenolysis as well as that of PCK1 and G6PC for gluconeogenesis (Fig. 4E to J). CREBH acetylation at K294 is crucial for the interaction and synergy between CREBH and PPARα in regulating hepatic gluconeogenesis. Consistently, disruption of CREBH acetylation at K294 led to reduced blood glucose levels and increased hepatic glycogen levels in mice upon fasting (Fig. 4H to J). These results confirmed that posttranslational lysine acetylation is a critical regulatory event for CREBH function in maintaining glucose homeostasis over the circadian cycle or during starvation.

In summary, our studies revealed that CREBH functions as a key metabolic regulator that controls glucose homeostasis by regulating glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis under conditions of energy demand during the circadian cycle or in response to fasting (Fig. 5). As we demonstrated previously, CREBH is also required in order to maintain lipid homeostasis by regulating lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation during the daytime or upon fasting (7, 10, 14). Apparently, CREBH functions as a major transcriptional activator that drives the processes of lipid and glucose mobilization in response to energy demands. Whether dysfunction or hyperactivation of CREBH can alter the whole-body metabolism and behavior is an interesting question to be investigated in the future. Nevertheless, the identification of CREBH as a potent circadian regulator of lipid and glucose metabolism has important implications for the understanding and treatment of metabolic syndromes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

For a full description of the materials and methods used in this work, see the supplemental material.

Animal model.

All animal experiments were performed with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Wayne State University. Four-month-old male wild-type and CREBH knockout C57BL/6 mice were housed in 12-h light–12-h dark (LD) cycles with free access to food and water for at least 2 weeks before being switched to constant darkness (DD) for 24 h to allow endogenous clocks to run freely. Mice were euthanized with isoflurane followed by rapid cervical dislocation. Liver samples from 3 to 5 mice per time point per genotype were collected in constant darkness every 4 h for a 24-h period.

Measurement of hepatic glycogen and blood glucose levels.

To quantify hepatic glycogen levels, liver tissues from similar lobe regions of CREBH-null and WT control mice were collected over the circadian cycle, and glycogen was measured using commercial enzymatic kits according to the manufacturer's instructions (BioAssay Systems, Hayward, CA). Levels of hepatic glycogen are presented after normalization to liver mass. The blood glucose levels of the mice under constant darkness were measured every 6 h for 36 h with a OneTouch Ultra blood glucose meter (LifeScan, Milpitas, CA).

ChIP assays with mouse liver chromatin.

Mouse liver chromatin was fragmented to an average size of 500 bp by sonication and was then cleared of debris by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 30 min at 8°C. The supernatant was harvested and was diluted 10-fold with ChIP dilution buffer. Approximately 10 μg of fragmented chromatin was precleared by incubating with 2 μg/ml of rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz) for 1 h at 4°C, followed by 1 h of incubation with 50 μl protein G-agarose (Invitrogen). CREBH-binding complexes were pulled down by using 2 μg/ml of a rabbit anti-CREBH antibody developed in our laboratory (10). As controls, the precleared chromatin samples were pulled down using a rabbit antihemagglutinin (anti-HA) antibody (2 μg/ml). Immunoprecipitated chromatin fragments were reverse cross-linked, digested by proteinase K, and purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). The presence of CREBH in gene promoters in different circadian phases was quantified by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) and was expressed relative to the input genomic DNA as described previously (17). The sequences of the primers used for the ChIP-PCR assay are given in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

qRT-PCR analysis.

Total RNAs from mouse livers were isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Invitrogen). For quantitative real-time PCR analysis, the reaction mixture containing the cDNA template, primers, and SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) was run in a 7500 Fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). The sequences of the real-time PCR primers used in this study are given in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Fold changes in mRNA levels were determined after normalization to the level of the internal control, Arbp (acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein P0) or β-actin mRNA.

Statistics.

The results of experiments were analyzed by several statistical methods. The unpaired Mann-Whitney U test was used for nonparametric comparisons. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for parametric comparisons. Two-way ANOVA was used to distinguish the effects of genotypes from the effects of circadian time on gene expression, levels of mouse blood lipids and blood metabolites, and quantification of food intake. In all cases, P values of <0.05 were used to attribute statistical significance. When multiple testing procedures were implemented (i.e., multiple t tests), the Bonferroni correction was used.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Portions of this work were supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants DK090313 and ES017829 (to K.Z.) and American Heart Association grants 0635423Z and 09GRNT2280479 (to K.Z.).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.00048-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bass J, Takahashi JS. 2010. Circadian integration of metabolism and energetics. Science 330:1349–1354. doi: 10.1126/science.1195027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green CB, Takahashi JS, Bass J. 2008. The meter of metabolism. Cell 134:728–742. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bechmann LP, Hannivoort RA, Gerken G, Hotamisligil GS, Trauner M, Canbay A. 2012. The interaction of hepatic lipid and glucose metabolism in liver diseases. J Hepatol 56:952–964. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raddatz D, Ramadori G. 2007. Carbohydrate metabolism and the liver: actual aspects from physiology and disease. Z Gastroenterol 45:51–62. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-927394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng D, Lazar MA. 2012. Clocks, metabolism, and the epigenome. Mol Cell 47:158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang X, Downes M, Yu RT, Bookout AL, He W, Straume M, Mangelsdorf DJ, Evans RM. 2006. Nuclear receptor expression links the circadian clock to metabolism. Cell 126:801–810. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng Z, Kim H, Qiu Y, Chen X, Mendez R, Dandekar A, Zhang X, Zhang C, Liu AC, Yin L, Lin JD, Walker PD, Kapatos G, Zhang K. 2016. CREBH couples circadian clock with hepatic lipid metabolism. Diabetes 65:3369–3383. doi: 10.2337/db16-0298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang K, Shen X, Wu J, Sakaki K, Saunders T, Rutkowski DT, Back SH, Kaufman RJ. 2006. Endoplasmic reticulum stress activates cleavage of CREBH to induce a systemic inflammatory response. Cell 124:587–599. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang C, Wang G, Zheng Z, Maddipati KR, Zhang X, Dyson G, Williams P, Duncan SA, Kaufman RJ, Zhang K. 2012. Endoplasmic reticulum-tethered transcription factor cAMP responsive element-binding protein, hepatocyte specific, regulates hepatic lipogenesis, fatty acid oxidation, and lipolysis upon metabolic stress in mice. Hepatology 55:1070–1082. doi: 10.1002/hep.24783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim H, Mendez R, Zheng Z, Chang L, Cai J, Zhang R, Zhang K. 2014. Liver-enriched transcription factor CREBH interacts with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α to regulate metabolic hormone FGF21. Endocrinology doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JH, Giannikopoulos P, Duncan SA, Wang J, Johansen CT, Brown JD, Plutzky J, Hegele RA, Glimcher LH, Lee AH. 2011. The transcription factor cyclic AMP-responsive element-binding protein H regulates triglyceride metabolism. Nat Med 17:812–815. doi: 10.1038/nm.2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee MW, Chanda D, Yang J, Oh H, Kim SS, Yoon YS, Hong S, Park KG, Lee IK, Choi CS, Hanson RW, Choi HS, Koo SH. 2010. Regulation of hepatic gluconeogenesis by an ER-bound transcription factor, CREBH. Cell Metab 11:331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roach PJ, Depaoli-Roach AA, Hurley TD, Tagliabracci VS. 2012. Glycogen and its metabolism: some new developments and old themes. Biochem J 441:763–787. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim H, Mendez R, Chen X, Fang D, Zhang K. 2015. Lysine acetylation of CREBH regulates fasting-induced hepatic lipid metabolism. Mol Cell Biol 35:4121–4134. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00665-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rutter J, Reick M, McKnight SL. 2002. Metabolism and the control of circadian rhythms. Annu Rev Biochem 71:307–331. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.090501.142857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oishi K, Shirai H, Ishida N. 2005. CLOCK is involved in the circadian transactivation of peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) in mice. Biochem J 386:575–581. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kapatos G, Vunnava P, Wu Y. 2007. Protein kinase A-dependent recruitment of RNA polymerase II, C/EBPβ and NF-Y to the rat GTP cyclohydrolase I proximal promoter occurs without alterations in histone acetylation. J Neurochem 101:1119–1133. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04486.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.