Abstract

Background

Anastomotic thrombosis following free tissue transfer (FTT) on or after day 5 (“late thrombosis”) is reported to have extremely low rates of salvage. Analysis of our institution’s experience with FTT was performed in order to make recommendations about the optimal management of late thrombosis, and to identify any variables that are correlated with increased salvage rates.

Methods

The study included patients who underwent FTT between 1986 and 2014, then suffered anastomotic thrombosis on or after postoperative day 5. Twenty-six variables involving demographic information, flap characteristics, circumstances of the thrombotic event, and details of any salvage attempt were analyzed. Patients whose FTT were successfully salvaged and those whose were not were statistically compared.

Results

Of the 3,212 patients who underwent FTT, 23 suffered late thrombosis (0.7%), and the salvage rate was 60.8% (14 of 23). The salvage rate for reconstruction of the head and neck was 53.3%, breast was 66.7%, and extremity was 100%. There was a statistically significantly greater salvage rate in flaps performed after 1998 than in those performed before 1998 (p=0.023). There was a non-statistically significant trend towards increased salvage rates in patients who had no anastomotic thrombotic risk factors, reconstruction using fasciocutaneous flaps, and anastomotic revision using new recipient vessels.

Conclusion

Our data demonstrate that flap survival after episodes of late thrombosis can be higher than the literature has previously reported. This underscores the importance of rigorous post-operative monitoring, as well as the importance of exploration at the earliest instance of concern for threatened flap viability.

Keywords: late thrombosis, free flap, free tissue transfer, salvage

Introduction

Thrombosis of either the arterial or venous microsurgical anastomosis is one of the most serious complications that can occur following free tissue transfer (FTT), as it has the potential to lead to catastrophic flap failure or even death. If the onset of thrombosis is recognized promptly, however, vascular inflow and outflow can be reestablished and the tissue can have a high likelihood of survival.

Retrospective analyses of large patient series have repeatedly shown that the risk of thrombosis is highest in the first 48 hours1–3, and decreases thereafter. When thrombosis occurs prior to postoperative day 5, it is commonly deemed “early thrombosis,” and is reported to have an incidence of 2–5% and a successful salvage rate of 24–60%4–5. Conversely, thrombosis that first occurs on postoperative day 5 or later is deemed by most authors to be “late thrombosis.” This is a relatively rare occurrence, as the published literature reports an incidence of 0.7–2%4–7.

When late thrombosis does occur, however, the literature to date suggests that successful salvage of the threatened tissue is much lower than in cases of early thrombosis, with reported rates in the range of 0–12%4–7. The reason for this significantly lower salvage rate is almost certainly multifactorial, likely owing to differences in the physiology, inflammatory profile, and hemodynamics compared to the earlier postoperative period. Additionally, identification of the occurrence of thrombosis in this late period is usually not as prompt, and it is well established that the likelihood of tissue injury becoming irreversible increases with increasing duration of the ischemic insult.

While operative exploration is the near-universal recommendation for early thrombosis, there is no consensus on the most appropriate modalities used to attempt salvage in episodes of late thrombosis. The literature has many reports that suggest the use of non-operative techniques such as anticoagulation and thrombolysis in these circumstances8–10.

All of the available recommendations, however, are based on heterogeneous patient series with small sample sizes. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to analyze our institution’s 28-year experience with FTT in order to make evidence-based recommendations about the optimal management of late thrombosis, and while doing so, to identify any patient-, flap-, or management-specific variables that are correlated with increased salvage rates.

Methods

After receiving Institutional Review Board approval, a retrospective review was undertaken of the prospectively maintained surgical database of microsurgical reconstructions performed by the Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC). The patients included in the study were those who had undergone FTT during the 28-year period between 1986 and 2014, and then suffered anastomotic thrombosis in the postoperative period. This time period was further analyzed based on the periods from 1986–1998, and from 1998–2014, as there was a clear difference in salvage rates between those two periods.

The patients were divided into 2 groups based on the postoperative day of the initial anastomotic thrombotic event, with early thrombosis defined as thrombosis prior to postoperative day 5, and late thrombosis defined as thrombosis on or after postoperative day 5. Twenty-six distinct variables were recorded, which were subdivided into categories: demographic information (including personal and family medical comorbidities), flap characteristics, circumstances of the thrombotic event, and details of any salvage attempt. An aggregate measure of anastomotic thrombotic risk factors was used that is defined as the presence of one or more of the following variables: current tobacco smoking, personal history of a hypercoagulable state, family history of a hypercoagulable state, or perioperative deep venous thrombosis. Successful salvage was defined as survival of the flap such that minimal-to-no tissue was lost or ultimately debrided (regardless of the pedicle patency).

Patients whose FTT was successfully salvaged after late thrombosis and those whose FTT were not salvaged were compared using Fisher’s exact test (Graphpad Software, Inc; San Diego, CA). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Patient inclusion criteria (Figure 1)

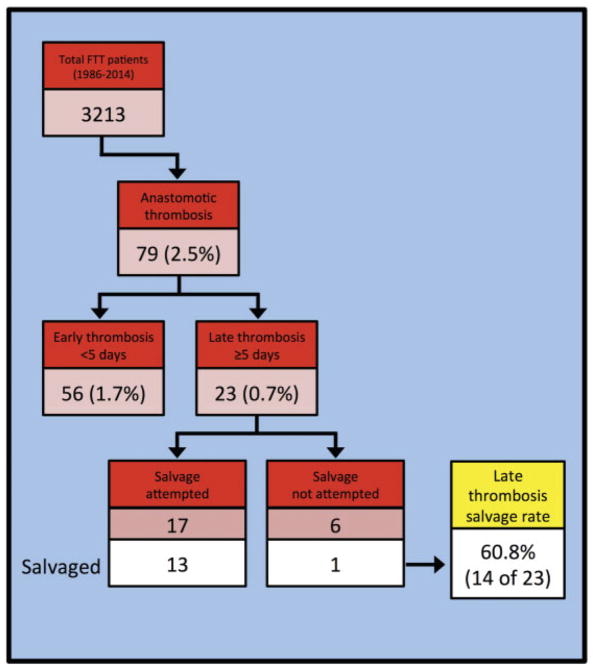

Figure 1.

Identification of cases of late anastomotic thrombosis, with salvage rate

Between 1986 and 2014, 3,213 patients underwent FTT procedures at MSKCC. Seventy-nine (2.5%) suffered postoperative flap thrombosis. Of those, 56 (70.8% of those who suffered thrombosis, and 1.7% of all patients who underwent FTT) had thrombosis occur on postoperative days 0–4, and 23 (29.2% of those who suffered thrombosis, and 0.7% of all patients who underwent FTT) had thrombosis occur on or after postoperative day 5.

Patient demographics (Table 1)

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| n | 23 |

| Gender (% female) | 82.6% |

| Age (y) | |

| Mean (range) | 58.2 (28–89) |

| Body mass index | |

| Mean (range) | 22.1 (17–33) |

| Flap recipient site | |

| Breast | 6 |

| Head and neck | 15 |

| Extremity | 2 |

| Diagnosis | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 12 |

| Breast cancer | 4 |

| Breast (benign) | 3 |

| Mesenchymal | 2 |

| Basal cell carcinoma | 1 |

| Melanoma | 1 |

Of the 23 patients who suffered late thrombosis, 82.6% were female, they had a mean age of 58.2 years (range: 28–89 years), and they had a mean body mass index (BMI) of 22.1 (range: 17–33). The reconstruction was performed in the head and neck region (n=15, 65.2%), breast (n=6, 26.0%), and extremity (n=2, 8.7%). The underlying diagnosis that necessitated oncologic resection and subsequent reconstruction included squamous cell carcinoma (SCC, n=12), breast cancer (n=4), benign breast disease (n=3), mesenchymal tumors (n=2), basal cell carcinoma (BCC, n=1), and melanoma (n=1).

Salvage rate based on patient demographics (Table 2)

Table 2.

Late anastomotic salvage rates, by patient characteristics

| n | Salvage rate (%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 23 | 60.8 | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 19 | 68.4 | NS |

| Male | 4 | 25.0 | |

| Age (y) | |||

| <50 | 8 | 62.5 | NS |

| ≥ 50 | 15 | 60.0 | |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 12 | 58.3 | NS |

| Breast cancer | 4 | 75.0 | |

| Breast (benign) | 3 | 33.3 | |

| Mesenchymal | 2 | 50.0 | |

| Basal cell carcinoma | 1 | 100.0 | |

| Melanoma | 1 | 100.0 | |

| Body mass index | |||

| <23 | 7 | 71.4 | NS |

| ≥ 23 | 10 | 70.0 | |

| Unknown | 6 | 33.3 | |

| Preoperative chemotherapy | |||

| Yes | 4 | 50.0 | NS |

| No | 18 | 61.1 | |

| Unknown | 1 | 100.0 | |

| Preoperative radiation | |||

| Yes | 12 | 58.3 | NS |

| No | 10 | 60.0 | |

| Unknown | 1 | 100.0 | |

| Thrombotic risk factors | |||

| 0 | 12 | 75.0 | NS |

| ≥ 1 | 7 | 57.1 | |

| Unknown | 4 | 25.0 | |

Overall, the salvage rate for patients suffering late anastomotic thrombosis was found to be 60.8% (14 of 23). There was no significant difference in salvages rates (p > 0.05) when considering demographics or risk factors, including gender, age, underlying diagnosis, BMI, preoperative chemotherapy or radiation, or anastomotic thrombotic risk factors (though there was a non-statistically significant trend towards late thrombosis in patients with one or more anastomotic risk factors).

Salvage rates based on flap characteristics (Table 3)

Table 3.

Late anastomotic salvage rates, by flaps characteristics

| n | Salvage rate (%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 23 | 60.8 | |

| Flap donor site | |||

| Abdomen | 9 | 55.5 | NS |

| Back | 2 | 100.0 | |

| Head and neck | 1 | 0.0 | |

| Intestine | 2 | 0.0 | |

| Lower extremity | 3 | 66.7 | |

| Upper extremity | 6 | 83.3 | |

| Flap type | |||

| Osteocutaneous | 3 | 66.7 | NS |

| Enteric | 2 | 0.0 | |

| Fasciocutaneous | 9 | 88.9 | |

| Musculocutaneous | 9 | 44.4 | |

| Flap recipient site | |||

| Breast | 6 | 66.7 | NS |

| Head and neck | 15 | 53.3 | |

| Extremity | 2 | 100.0 | |

| Arterial anastomosis | |||

| End-to-end | 20 | 65.0 | NS |

| End-to-side | 2 | 50.0 | |

| Unknown | 1 | 0.0 | |

| Venous anastomosis | |||

| Coupler | 4 | 25.0 | NS |

| End-to-end | 13 | 61.5 | |

| End-to-side | 4 | 100.0 | |

| Unknown | 2 | 0.0 | |

The FTT donor site-specific salvages rates were 100% for back (2 of 2), 83.3% for upper extremity (5 of 6), 66.7% for lower extremity (2 of 3), 55.5% for abdomen (5 of 9), and 0% for both head and neck (0 of 1) and for enteric (0 of 2) donor sites. Fasciocutaneous flaps were salvaged in 88.9% of cases, (8 of 9), osteocutaneous flaps were salvaged in 66.7% (2 of 3), musculocutaneous flaps were salvaged in 44.4% (4 of 9), and enteric flaps were never salvaged (0 of 2). Salvage rates based on flap recipient sites were 100% for extremity (2 of 2), 53.3% for head and neck (8 of 15), and 66.7% for breast (4 of 6). Salvage rates based on arterial anastomosis technique at the index operation included: 50% for end-to-side (1 of 2), and 65% for end-to-end (13 of 20). Salvage based on venous anastomosis at the index operation included: 100% for end-to-side (4 of 4), 61.5% for end-to-end (7 of 12), and 25% for anastomosis using the GEM microsurgical coupling device (Synovis; Birmingham, AL) (1 of 4).

Salvage rates based on details of thrombotic event (Table 4 and Figure 2)

Table 4.

Late anastomotic salvage rates, by thrombotic event

| n | Salvage rate (%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 23 | 60.8 | |

| How identified | |||

| Appearance | 11 | 81.8 | NS |

| Loss of Doppler signal | 5 | 80.0 | |

| Endoscopy | 1 | 0.0 | |

| Skin dehiscence | 1 | 0.0 | |

| Temperature change | 1 | 0.0 | |

| Unknown | 4 | 25.0 | |

| Where identified | |||

| Inpatient | 20 | 65.0 | NS |

| Outpatient | 3 | 33.0 | |

| Arterial or venous | NS | ||

| Arterial | 6 | 83.0 | |

| Venous | 12 | 75.0 | |

| Unknown | 5 | 0.0 | |

| POD occurred | |||

| Day 5 to 6 | 14 | 71.4 | NS |

| Day 7 or later | 9 | 44.4 | |

| Year performed | |||

| 1986 to 1997 | 8 | 25.0 | 0.023 |

| 1998 to 2014 | 15 | 80.0 | |

| Salvage attempted? | |||

| Yes | 17 | 76.4 | 0.018 |

| No | 6 | 16.7 | |

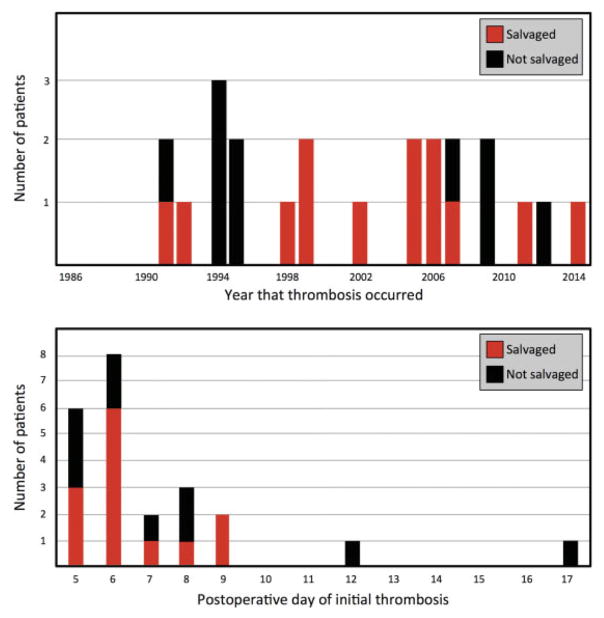

Figure 2.

Late anastomotic salvage, by year (above) and by postoperative day of thrombosis (below)

The salvage rates for means by which thrombosis was identified included: color change 81.8% (9 of 11), loss of Doppler signal 80% (4 of 5), temperature change 0% (0 of 1), endoscopic findings 0% (0 of 1), and skin dehiscence revealing ischemic flap 0% (0 of 1). The salvage rate if identified as an inpatient was 65% (13 of 20), and if identified as an outpatient was 33.3% (1 of 3) (p=0.538).

Of the 23 patients, 6 occurred on postoperative day 5, and 8 occurred on postoperative day 6. The salvage rate of these 14 patients was 71.4%%, and the salvage rate for the patients whose late thrombosis occurred on postoperative day 7 or later was 44.4% (p=0.417). The latest anastomotic thrombosis occurred on postoperative day 17, and the latest thrombosis that was successfully salvaged occurred on postoperative day 9.

When late thrombosis did occur, salvage rates when the thrombosis was arterial in origin was 83.0% (5 of 6), when the thrombosis was venous in origin was 75% (9 of 12), and when the etiology was uncertain was 0% (0 of 5).

During the study period there were an average of 0.8 patients per year who suffered an episode of late thrombosis (range: 0–3). The salvage rate from 1986–1997 was 25.0%, and from 1998–2014 was 80.0% (p=0.023).

Attempts at flap salvage were undertaken in 17 of the 23 patients, and the successful salvage rate was 76.4%.

Salvage rates based on salvage attempt intraoperative details (Table 5)

Table 5.

Late anastomotic thrombosis salvage rates, by intraoperative management decision

| n | Salvage rate (%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operative salvage attempted | 17 | 76.4 | |

| Time to salvage incision | |||

| < 135 min | 9 | 88.9 | NS |

| ≥ 135 min | 3 | 66.7 | |

| Unknown | 5 | 36.0 | |

| Fogarty thrombectomy | |||

| Yes | 5 | 80.0 | NS |

| No | 12 | 75.0 | |

| Intraoperative thrombolysis | |||

| Yes | 8 | 75.0 | NS |

| No | 9 | 77.8 | |

| Anastomosis revised | |||

| Yes | 15 | 80.0 | NS |

| No | 2 | 50.0 | |

| Vein graft | |||

| Yes | 7 | 71.4 | NS |

| No | 8 | 87.5 | |

| Same vessels or new vessels? | |||

| Same | 11 | 72.7 | NS |

| New | 4 | 100.0 | |

The mean time from clinical suspicion to operative incision was 135.7 minutes (range: 45–287); the salvage rate was 88.9% if incision was made in <135 minutes, and was 66.7% if incision was made in ≥135 minutes. Fogarty catheter thrombectomy was performed in 5 of 17 salvage attempts; successful salvage was achieved in 80.0% of cases when thrombectomy was performed, and in 75.0% of cases when thrombectomy was not performed (p=1.000). Intraoperative thrombolysis was performed in 8 of 17 salvage attempts; successful salvage was achieved in 75% of case when thrombolysis was performed, and in 77.8% of cases when thrombolysis was not performed (p=1.000). The thrombosed anastomosis was revised in 15 of 17 cases; successful salvage was achieved in 80.0% of cases when the anastomosis was revised, and in 50.0% of cases when the anastomosis was not revised (p=0.515).

In those cases in which the anastomosis was revised, saphenous vein graft (SVG) was utilized in 7 of 15 cases; successful salvage was achieved in 71.4% of cases when vein graft was utilized, and in 87.5% of cases when vein graft was not utilized (p=0.569). When the same recipient vessels were used for the revised anastomosis (with or without an intervening SVG), the salvage rate was 72.7%, and when new recipient vessels were used the salvage rate was 100% (p=0.517).

Discussion

As the potential applications for FTT techniques are continuously increasing, it is increasingly important that as much as possible is understood about the potential complications that can occur after microsurgical vascular manipulation. The data compiled and analyzed in this study moves towards that goal, and has resulted in 3 sets of conclusions that we believe have important clinical and logistical implications.

The first set of conclusions involves the incidence of late thrombosis after FTT and its optimal management. Our data confirm that, while fortunately a rare occurrence (0.7% of all FTT in our series), anastomotic thrombosis can happen on postoperative day 5 or later. More importantly, despite previous reports suggesting that salvage is extremely rare in situations of late thrombosis4–6, our data show that threatened FTT can often be successfully salvaged, as we had an overall salvage rate of 60.8% in our series. Given that late thrombosis can and does occur, and that the potential for successful salvage is higher than previously reported, we strongly advocate for intensive flap monitoring in the initial post-operative period (both in terms of frequency as well as in duration), as well as for rapid operative intervention when there is suspicion of thrombosis.

In this era of enhanced recovery protocols and shortened hospitalization after undergoing FTT (particularly in microvascular breast reconstruction)11–15, we believe it is important to point out that our data reinforce our clinical opinion that favors ongoing flap monitoring. The protocol at our institution is for flap checks every 1 hour for the first 48 hours, every 2 hours for the next 48 hours, every 4 hours for the next 48 hours, and every 8 hours after that. While most patients who had free tissue transfer for head and neck reconstruction stay in the hospital for 7–14 days, most patients who have free tissue transfer for breast reconstruction are discharged from the hospital within 3–5 days. When any patient is discharged from the hospital – but especially those who leave within the critical monitoring period of 7–10 days – they have been extensively educated to look for the signs of arterial and venous insufficiency.

Regardless of the time point at which inpatient monitoring ceases and the patient is discharged home, we believe that a necessary element of effective outpatient care is open and easy communication between the patient and the surgical team, and we therefore make that a point of emphasis. We have found this to be facilitated by simple text messaging and smartphone-based photography. For example, one patient in the series noted an acute change in the gross appearance and temperature of her reconstructed breast while at home on postoperative day 5. She sent a photograph of her surgical site via text message, and was advised to come immediately to the hospital for exploration (where operating room logistics had been able to be initiated even before she arrived). The flap had an arterial thrombosis that was revised, and the flap survived.

Close monitoring in order to facilitate early identification would be of no benefit if there is a lack of institutional and operational capabilities to facilitate prompt operative exploration. At our institution we have created a streamlined process, as well as a culture, that allows for expedited return to the operating room during these very time-sensitive emergencies. This has allowed us to achieve an average interval of 135 minutes between onset of suspicion and actual surgical incision. We believe the onset of clinical suspicion of thrombosis is the limiting step, and the subsequent transfer from hospital floor to operating room table is rapid and largely automated. As a tertiary referral center, our institution often cares for patients who live outside of the region. Especially when they are discharged within the first 10 days, patients are strongly encouraged to stay in the area for several days (and are made aware that if a late problem develops and they are not able to return, there is a possibility they may lose the reconstruction).

Some published reports advocate for non-operative management in cases of anastomotic thrombosis, such as anticoagulation, systemic thrombolysis, and catheter-based thrombolysis8–10. While this may be appropriate in certain selective circumstances, we feel that in the overwhelming majority of cases operative exploration is the most appropriate course of action.

The second set of conclusions involves the attempt to achieve a more granular understanding of the relative significance of both modifiable and non-modifiable variables (including demographics, flap characteristics, details of the thrombotic event, and intraoperative details of any salvage attempt) on salvage rate after FTT thrombosis.

Given that FTT thrombosis is so rare, the sample size of this study is small. Accordingly, statistical significance was difficult to achieve. There was only one variable that did achieve strict statistical significance: the year in which the procedure was performed. Namely, there was a statistically significantly greater likelihood of successful salvage after late thrombosis if the procedure was performed after 1998 as opposed to before 1998. While it is impossible to retrospectively ascertain the exact etiology of this, it likely involved increased experience of the surgical and nursing staffs with FTT, and a decrease in the time to exploration.

Though there were no other variables that were statistically significantly correlated with salvage in cases of late anastomotic thrombosis, we believe that are a number of findings that warrant discussion, as the trends are suggestive of findings that would likely achieve statistical significance if more episodes of this uncommon and heterogeneous entity could be captured.

First, we have a high suspicion that underlying hematologic/thrombotic abnormalities may play a role in the onset of thrombosis (especially late thrombosis), as well as decreased salvage rates when thrombosis does occur. This suspicion is borne of the fact that within the past 5 years, we have had 2 non-salvaged episodes of late thrombosis in which patients also had perioperative deep vein thrombosis. In our analysis we separated the patients who suffered late thrombosis into two groups based on whether they had any of four risk factors for anastomotic thrombosis (personal history of hematologic disorder, family history of hematologic disorder, perioperative thromboembolic event, or status as a current smoker), and we found a trend towards lower salvage rates when at least one of the risk factors was present. Accordingly, at our institution patients who have suffered late anastomotic thrombosis undergo formal hematologic work-up as a matter of routine – previously undiagnosed hematologic abnormalities have now been diagnosed in two patients (neither of which were successfully salvaged). We have altered our preoperative practice and now focus on more thorough pre-procedural investigation for bleeding disorders (with abnormal history, physical exam, or laboratory values prompting formal hematologic work-up). Of note, interesting work has been done by Handschel et al16 regarding the use of traditional serum coagulation assays, and by Kolbenschlag et al17 regarding the use of rotational thromboelastography to identify patients with clotting abnormalities, and we look forward to ongoing research on this very important topic.

After a patient has been determined to be at high risk for anastomotic thrombotic events, it is important to determine how patients should be clinically managed when hematologic abnormality is diagnosed prior to the procedure. After reviewing the literature, it is found that Lin et al18 and Ozkan et al19 have shown that FTT can be safely performed in patients with documented hematologic abnormalities. Wang et al20, however, found in their series that the incidence of thrombosis was higher than in patients without hematologic abnormalities, and strikingly found the salvage rate after thrombosis to be 0% (compared to 60% in patients without hematologic abnormalities). This rate is lower than was found in our series, and furthermore their patients suffered thrombosis on mean post-operative day 3.5, whereas ours were by definition on post-operative day 5 or later. This is a clinical question we will be addressing ourselves in subsequent research.

Second, osteocutaneous and fasciocutaneous flaps trended towards higher salvage rate than musculocutaneous flaps (and certainly higher salvage rates than enteric flaps). This finding is in line with the current understanding of the relative metabolic demands of skin and subcutaneous tissue relative to muscle, and especially intestine21–22. Though musculocutaneous flaps continue to be the workhorse flaps for most reconstructive procedures, this finding lends additional evidence-based support for the theoretical benefit of osteocutaneous and fasciocutaneous flaps, and may continue the slow but steady transition towards the clinical preference for these flaps.

Third, when operative attempts were made at salvage and the vascular anastomosis was revised, there was a trend towards higher salvage rates in those patients who had the vascular anastomosis redone with a different recipient vessel, as opposed to the same recipient vessel that was used at the index operation. Of note, the use of SVG did not have any appreciable effect either for or against successful salvage (71.4% when SVG used vs. 87.5% when SVG was not used). Therefore, we advocate for use of alternative recipient vessels whenever possible, as even grossly uninjured vessels likely have suffered some degree of endothelial injury, and every possible measure should be taken at reoperation to reduce the likelihood of recurrence of vascular compromise.

Fourth, in evaluating the finding that the salvage rate of venous anastomoses performed using the coupling device compared to a hand-sewn technique, it is important to remember that the sample size available in this study is very low because of the very narrowly defined subgroup, and so while the salvage rate was higher in the hand-sewn group compared to the coupled group (61% vs. 25%), that difference was not statistically significant. Furthermore, we believe that the most important outcome related to venous coupling is the equivalence (or perhaps even superiority), of coupling in terms of primary patency, a finding that our group has shown in a recent publication.23

The major limitation of this study has already been highlighted, as the relatively small sample size precluded our attaining statistical significance in all but one measure. As our already-extensive series continues to grow, we may be able to attain statistical significance, but that would be at the expense of further exacerbating the already confounding variables such as changes in practice and technology, as well as general improvements in our collective understanding of microvascular physiology.

Conclusion

In summary, analysis of our 28-year experience with FTT demonstrates that flap survival after episodes of late thrombosis can be higher than the literature has reported. We believe that this finding underscores the importance of rigorous post-operative monitoring (both by physicians as an inpatient, as well as by the patients themselves after they have transitioned to the outpatient setting), and the importance of early operative exploration at the earliest instance of concern for threatened flap viability. Additionally, we have found a number of clinical variables in the pre-, intra-, and post-thrombotic period that are correlated with trends towards higher salvage rates, and are put forth as concepts to take into consideration when microsurgeons are faced with this challenging clinical scenario.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

References

- 1.Kroll S, Schusterman M, Reece G, et al. Timing of pedicle thrombosis and flap loss after free-tissue transfer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98(7):1230–3. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199612000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Novakovic D, Patel RS, Goldstein DP, Gullane PJ. Salvage of failed free flaps used in head and neck reconstruction. Head Neck Oncol. 2009;1:33. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-1-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshimotoa S, Kawabataa K, Mitani H. Analysis of 59 cases with free flap thrombosis after reconstructive surgery for head and neck cancer. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2010;37(2):205–11. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kadota H, Sakuraba M, Kimata Y, Yano T, Hayashi R. Analysis of thrombosis on postoperative day 5 or later after microvascular reconstruction for head and neck cancers. Head Neck. 2009;31(5):635–41. doi: 10.1002/hed.21021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu P, Chang DW, Miller MJ, Reece G, Robb GL. Analysis of 49 cases of flap compromise in 1310 free flaps for head and neck reconstruction. Head Neck. 2009;31(1):45–51. doi: 10.1002/hed.20927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyodo I, Nakayama B, Kato H, et al. Analysis of salvage operation in head and neck microsurgical reconstruction. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(2):357–60. doi: 10.1097/mlg.0b013e3180312380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ribuffo D, Chiummariello S, Cigna E, Scuderi N. Salvage of free flap after late total thrombosis of the flap and revascularization. Scand J Plast Recon Surg Hand Surg. 2004;38(1):50–2. doi: 10.1080/02844310310007872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anavekar NS, Lim E, Johnston A, Findlay M, Hunter-Smith DJ. Minimally invasive late free flap salvage: indications, efficacy and implications of reconstructive microsurgeons. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(11):1517–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2011.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trussler AP, Watson JP, Crisera CA. Late free-flap salvage with catheter-directed thrombolysis. Microsurg. 2008;28(4):217–22. doi: 10.1002/micr.20480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ihler F, Matthias C, Canis M. Free flap salvage with subcutaneous infection of tissue plasminogen activator in head and neck patients. Microsurgery. 2013;33:478–81. doi: 10.1002/micr.22132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guidera AK, Kelly BN, Rigby P, MacKinnon CA, Tan ST. Early oral intake after reconstruction with a free flap for cancer of the oral cavity. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surgeyr. 2013;51(3):224–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kakarala K, Emerick KS, Lin DT, Rocco JW, Deschler DG. Free flap reconstruction in 1999 and 2009: changing case characteristics and outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(10):2160–3. doi: 10.1002/lary.23457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryan MW, Hochman M. Length of stay after free flap reconstruction of the head and neck. Laryngoscope. 2000;110(2 Pt 1):210–6. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200002010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeung JK, Dautremont JF, Harrop AR, et al. Reduction of pulmonary complications and hospital length of stay with a clinical care pathway after head and neck reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133(6):1477–84. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allak A, Nguyen TN, Shonka DC, Jr, et al. Immediate postoperative extubation in patients undergoing free tissues transfer. Laryngoscope. 2001;121(4):763–8. doi: 10.1002/lary.21397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Handschel J, Burghardt S, Naujoks C, et al. Paremeters predicting complications in flap surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;115:589–94. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolbenschlag J, Daigleler A, Lauer S, et al. Can rotational thromboelastometry predict thrombotic complications in reconstructive microsurgery. Microsurgery. 2014;34:253–60. doi: 10.1002/micr.22199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin PY, Cabrera R, Chew KY, Kuo YR. The outcome of free tissue transfers in patients with hematological diseases: 20-year experience in single microsurgical center. Microsurgery. 2014;34:505–10. doi: 10.1002/micr.22243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ozkan O, Chen HC, Mardini S, et al. Microvascular free tissue transfer in patients with hematological disorders. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118:936–44. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000232371.69606.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang TY, Serletti JM, Cuker A, et al. Free tissue transfer in the hypercoagulable patient: review of 58 flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:443–53. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31823aec4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eichhorn W, Blake FA, Pohlenz P, et al. Conditioning of myocutaneous flaps. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2009;37(4):196–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mallick IH, Yang W, Winslet MC, Seifalian AM. Ischemia-reperfusion injury of the intestine and protective strategies against injury. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49(9):1359–77. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000042232.98927.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kulkarni AR, Mehrara BJ, Pusic AL, Cordeiro PG, Matros E, McCarthy CM, Disa JJ. Venous thrombosis in handsewn versus coupled venous anastomoses in 857 consecutive breast free flaps. J Recon Microsurg. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1563737. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]