Abstract

Bacterial endophthalmitis is a potentially blinding intraocular infection. The bacterium Bacillus cereus causes a devastating form of this disease which progresses rapidly, resulting in significant inflammation and loss of vision within a few days. The outer surface of B. cereus incites the intraocular inflammatory response, likely through interactions with innate immune receptors such as TLRs. This study analyzed the role of B. cereus pili, adhesion appendages located on the bacterial surface, in experimental endophthalmitis. To test the hypothesis that the presence of pili contributed to intraocular inflammation and virulence, we analyzed the progress of experimental endophthalmitis in mouse eyes infected with wild type B. cereus (ATCC 14579) or its isogenic pilus-deficient mutant (ΔbcpA-srtD-bcpB or ΔPil). One hundred CFU were injected into the mid-vitreous of one eye of each mouse. Infections were analyzed by quantifying intraocular bacilli and retinal function loss, and by histology from 0 to 12 h postinfection. In vitro growth and hemolytic phenotypes of the infecting strains were also compared. There was no difference in hemolytic activity (1:8 titer), motility, or in vitro growth (p>0.05, every 2 h, 0-18 h) between wild type B. cereus and the ΔPil mutant. However, infected eyes contained greater numbers of wild type B. cereus than ΔPil during the infection course (p≤0.05, 3-12 h). Eyes infected with wild type B. cereus experienced greater losses in retinal function than eyes infected with the ΔPil mutant, but the differences were not always significant. Eyes infected with ΔPil or wild type B. cereus achieved similar degrees of severe inflammation. The results indicated that the intraocular growth of pilus-deficient B. cereus may have been better controlled, leading to a trend of greater retinal function in eyes infected with the pilus-deficient strain. Although this difference was not enough to significantly alter the severity of the inflammatory response, these results suggest a potential role for pili in protecting B. cereus from clearance during the early stages of endophthalmitis, which is a newly described virulence mechanism for this organism and this infection.

Keywords: eye, infection, endophthalmitis, inflammation, virulence, Bacillus, pili

1. Introduction

Bacillus cereus causes a form of severe intraocular infection (endophthalmitis) which progresses rapidly, resulting in significant inflammation and loss of vision within a few days. In severe cases, B. cereus endophthalmitis may lead to enucleation or evisceration of the infected eye (Chan et al., 2003, Chen and Roy, 2000, Cowan et al., 1997, David et al., 1994, O'Day et al., 1981, and Roy et al., 1997). This devastating outcome may occur regardless of antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory therapies that may be successful against staphylococcal or streptococcal endophthalmitis (Astley et al., 2016, Callegan et al., 2007, and Sadaka et al., 2012). Therefore, identifying the specific factors of B. cereus which contribute to its unique intraocular virulence is important in devising better treatment strategies for this disease.

During experimental endophthalmitis, the outer envelope of B. cereus incites an intraocular inflammatory response (Callegan et al., 1999). This acute response is likely mediated by interactions between peptidoglycan found on the surface of B. cereus and Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), an innate immune receptor which recognizes Gram-positive peptidoglycan (Novosad et al., 2011). TLR4 and its adaptor molecules MyD88 and TRIF are also important in the acute intraocular inflammatory response to B. cereus (Parkunan et al., 2015), but the ligand(s) initiating this response have not yet been identified. Flagella also contribute to the intraocular virulence of B. cereus, primarily through their function in propelling the organism throughout the eye during infection (Callegan et al., 2005 and Callegan et al., 2006), but not via interactions with TLR5 (Parkunan et al., 2014).

In an effort to identify factors associated with the unique virulence of this organism in the eye, we analyzed the role of B. cereus pili, which are adhesion appendages, in experimental endophthalmitis. A number of bacterial species rely on pili as a virulence determinant for adherence to mucosal tissues, to tissues in areas of high fluid flow, and in establishment of biofilms (Axner et al., 2011, Danne and Dramsi, 2012, Mandlik et al., 2008, Melville and Craig, 2013, Romero, 2013, Scheewind and Missiakas, 2012, and Vengadesan and Narayana, 2011). Engagement of pili with components of innate immunity has also been suggested, potentially contributing to the acute inflammatory response (Barrochi et al., 2006, Bassett et al., 2013, Crotty Alexander et al., 2010, and Vargas Gardia et al., 2015). Budzik et al. (2007, 2008, 2009a, and 2009b) have reported on the structure and assembly of pili on the surface of vegetative B. cereus, but a specific role for pili in B. cereus infections has not yet been ascribed. In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that B. cereus pili contributed to intraocular virulence in a well-established mouse model of B. cereus endophthalmitis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains

Bacterial strains used to initiate experimental endophthalmitis in mice included B. cereus ATCC 14579 or its isogenic pilus-deficient mutant (ΔbcpA-srtD-bcpB or ΔPil) (Budzik et al., 2007). The isogenic pilus-deficient mutant was generated by allelic replacement mutagenesis as previously described (Budzik et al., 2007). The in vitro growth, hemolytic titers, and motility of these strains were compared. Each strain was cultured for 18 h at 37°C with aeration in brain heart infusion (BHI; VWR, Radnor PA), then subcultured to an approximate concentration of 103 CFU/mL in fresh BHI. Subcultures were incubated for 18 h as described above. Every two hours, aliquots were removed to quantify bacteria by track dilution (see 2.3 below) and hemolytic activity. Aliquots were filter sterilized (0.22 μm; EMD Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) and supernatants were serially diluted 1:2 in PBS (pH 7.4). Supernatants were then mixed 1:1 with 4% (vol/vol) sheep erythrocytes (Rockland Immunochemicals, Pottstown PA) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. The hemolytic titer was determined to be the lowest dilution of supernatant exhibiting 50% hemolysis at an optical density of 540 nm. Strains were also incubated on tryptic soy agar (TSA) with 5% sheep blood agar for 18 h at 37°C for colony morphology and hemolytic phenotype comparisons, and on motility agar (0.75% agar in BHI) for motility phenotype comparisons. Strains were also compared by transmission electron microscopy (Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation Imaging Core, Oklahoma City OK). Lawns of B. cereus were scraped from BHI agar plates following 18 h growth at 37°C. Bacteria were suspended in PBS, fixed with 5% paraformaldehyde/4% glutaraldehyde, washed with water, and stained with 4% uranyl acetate. Samples were viewed with a Hitachi H-7600 transmission electron microscope.

2.2. Mice and Intraocular Infection

The in vivo experiments described herein involved the use of mice. All animal procedures were conducted according to guidelines and recommendations from the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), and the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. The OUHSC IACUC approved these studies under protocol 13-086.

C57BL/6J mice were purchased from commercially available stock colonies (Stock No. 000664, Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor ME). All mice were housed in microisolation conditions on a 12 h on/12 h off light cycle for at least two weeks before use, then under biosafety level 2 conditions during experiments. Mice were 8–10 weeks of age at the time of experiment.

Mice were anesthetized with a combination of ketamine (85 mg/kg body weight; Ketathesia, Henry Schein Animal Health, Dublin, OH) and xylazine (14 mg/kg body weight; AnaSed; Akorn Inc., Decatur, IL). Experimental B. cereus endophthalmitis was induced in mouse eyes by injecting approximately 100 CFU B. cereus/0.5 μl BHI into the mid-vitreous, as previously described (Moyer et al., 2009, Novosad et al., 2011, Parkunan et al, 2014, Parkunan et al., 2015, and Ramadan et al., 2008). The contralateral eye served as the uninjected/uninfected control. Mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation, which occurred before eyes were removed for analysis.

2.3. Bacterial Quantitation

Intraocular bacteria were quantified as previously described (Moyer et al., 2009, Novosad et al., 2011, Parkunan et al, 2014, Parkunan et al., 2015, and Ramadan et al., 2008). Whole eyes were removed from euthanized mice at 3, 6, 9, and 12 h postinfection. Eyes were homogenized in PBS with sterile 1mm glass beads (BioSpec Products, Inc., Bartlesville, OK). Homogenates were plated and bacterial numbers were quantified by the track dilution method. Values represent the mean ± SEM for N≥6 eyes per time point. Two independent experiments were performed.

2.4. Electroretinography

Electroretinography (ERG) was used to analyze retinal function, as previously described (Moyer et al., 2009, Novosad et al., 2011, Parkunan et al, 2014, Parkunan et al., 2015, and Ramadan et al., 2008). Scotopic ERGs were performed at 6, 9, and 12 h postinfection (Espion E2, Diagnosys LLC, Lowell MA). Following infection, mice were dark-adapted for at least 6 h. Mice were anesthetized with the ketamine/xylazine cocktail and pupils were dilated with topical phenylephrine (Akorn, Inc., IL). Retinal function was recorded with gold-wire electrodes placed on each cornea and a reference electrode. Retinal responses were stimulated by five white light flashes (1,200 cd·s/m2). The average of the resulting A- and B-wave amplitudes following each flash was calculated. A- and B-wave amplitudes were recorded for infected and contralateral uninfected eyes in the same animal. A- and B-wave amplitudes were measured from the initiation of the light flash to the trough of the A-wave, and the trough of the A-wave to the peak of the B-wave. The percentage of retinal function retained in the infected eye was calculated in comparison with uninfected left eye controls as: 100 – {[1 – (experimental A- or B-wave amplitude/control A- or B-wave amplitude) ]× 100}. Values represent the mean ± SEM for N≥6 eyes per time point. At least 3 independent experiments were performed.

2.5. Histology

Eyes were harvested at 3, 6, 9, and 12 h postinfection. Harvested eyes were incubated in buffered zinc formalin or Davidson's fixative for 24 h at room temperature (Moyer et al., 2009, Novosad et al., 2011, Parkunan et al, 2014, Parkunan et al., 2015, and Ramadan et al., 2008). Eyes were then transferred to 70% ethanol, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Images are representative of at least 3 eyes per time point from at least 2 independent experiments.

2.6. Statistics

Data are the arithmetic means ± the standard errors of the mean (SEM) of all samples in the same experimental group in replicate experiments. Statistical significance was p<0.05. The Mann Whitney Rank Sum test was used to compare experimental groups to determine the statistical significance for all assays (Parkunan et al., 2015, and Parkunan et al., 2016). All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.05 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla CA).

3. Results

3.1. Bacterial Growth and Phenotypes

B. cereus strains ATCC 14579 and ΔPil grew at similar rates in BHI (Figure 1A). Numbers of ATCC 14579 and ΔPil were statistically similar at each time point tested (P≥0.05). Both strains reached stationary phase in BHI at approximately 8 h postinfection. Figure 1B depicts inoculation of TSA with 5% sheep blood with B. cereus ATCC 14579 and ΔPil. Four areas on each blood agar plate were spot-inoculated and incubated at 37°C for 18 h. Spreading colonies of B. cereus were observed at each inoculation point, each with the characteristic double zone of hemolysis. On sheep blood agar (Figure 1B) and motility agar (ATCC 14579, 31.7 ± 9.5 mm; ΔPil, 31.3 ± 3.2 mm at 48 h, P=0.97), these strains were phenotypically indistinguishable. Hemolytic assays confirmed this observation, as hemolytic titers of 18-h supernatants of ATCC 14579 and ΔPil were similar (titer = 1:8, N=3). These results suggested that the absence of pili (Figure 1C) did not affect the in vitro growth, motility, or hemolytic phenotype and that, based on these similarities, in vivo infection with these strains might be equivalent.

Figure 1. In vitro growth of piliated and nonpiliated B. cereus.

(A) B. cereus ATCC 14579 or its isogenic pilus-deficient mutant (ΔPil) were cultured in BHI for 18 h at 37°C, then subcultured to an approximate concentration of 103 CFU/mL in fresh BHI. Aliquots were removed every two hours to quantify bacteria. Numbers of ATCC 14579 and ΔPil were statistically similar at each time point tested (P≥0.05). Both strains reached stationary phase in BHI at approximately 8 h postinfection. Values represent the mean ± SD for N=3 samples per time point. (B) B. cereus ATCC 14579 or its isogenic pilus-deficient mutant (ΔbcpA-srtD-bcpB) were spotted onto TSA + 5% sheep blood agar and incubated for 18 h at 37°C. Spreading colonies of B. cereus were observed at each inoculation point and colonies had the characteristic double zone of hemolysis. On blood agar, these strains were phenotypically indistinguishable. (C) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of ATCC 14579 (WT) and ΔPil. Pili are denoted by white arrows, while black arrows denote flagella or flagellar bundles. Pili were noted surrounding ATCC 14579, but not ΔPil. Magnification, 50,000X.

3.2. Intraocular Growth and Retinal Function

The intraocular growth of B. cereus ATCC 14579 and ΔPil in C57BL/6J mice is depicted in Figure 2. Eyes were inoculated with 112 ± 3 CFU/eye ATCC 14579 and 107 ± 4 CFU/eye ΔPil (P=0.26). The bacterial load in eyes infected with ATCC 14579 was significantly greater than the bacterial load in eyes infected with ΔPil at 3, 6, 9, and 12 h postinfection (P≤0.03). At 12 h postinfection, eyes infected with ATCC 14579 had 8.8 × 106 CFU/eye, while eyes infected with ΔPil had 5.2 × 105 CFU/eye (P=0.0003). The significant differences in CFU suggested that ocular infection by ΔPil might be less severe than that of infection with ATCC 14579.

Figure 2. Intraocular growth of piliated and nonpiliated B. cereus.

Eyes of C57BL/6J mice were infected with 100 CFU of B. cereus ATCC 14579 (WT) or its isogenic pilus-deficient mutant (ΔPil). Eyes were harvested and B. cereus were quantified. Greater numbers of WT B. cereus were recovered from infected eyes than ΔPil B. cereus at all postinfection time points (*P≤0.03). Values represent mean ± SEM of N≥6 eyes at each time point.

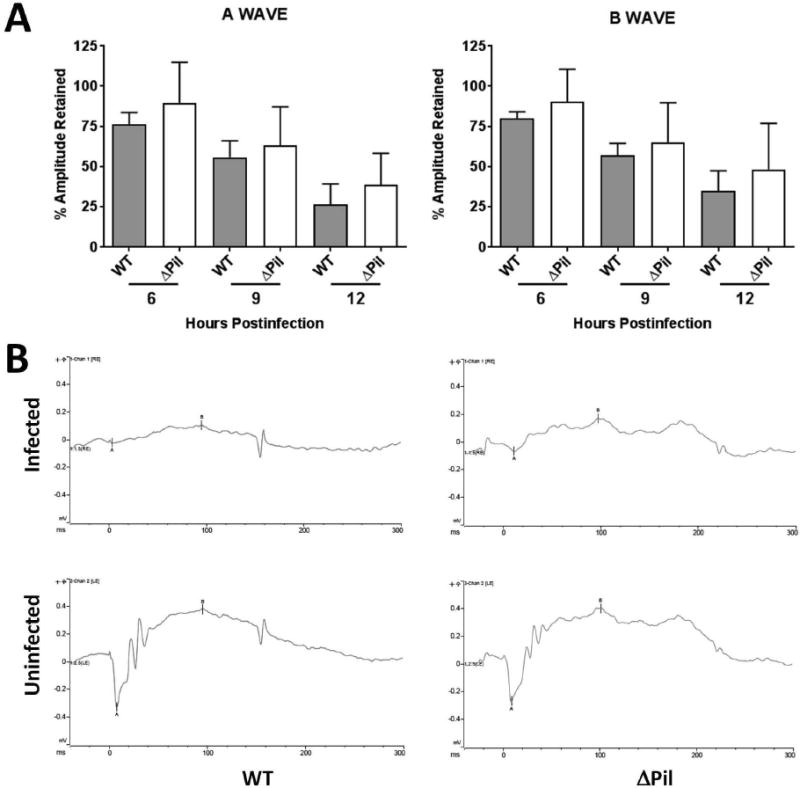

The retained retinal function of eyes infected with B. cereus ATCC 14579 or ΔPil and representative waveforms of these eyes are depicted in Figure 3. The retained A-wave function of eyes infected with ATCC 14579 decreased from 6 to 12 h postinfection, to a retained response of approximately 26%. The retained B-wave function in these eyes decreased over the same time period to approximately 39%. The retained A-wave function of eyes infected with ΔPil also decreased from 6 to 12 h postinfection, to a retained response of approximately 35%, while the retained B-wave function declined to approximately 48%. Although there was an observed trend of higher retained A-wave and B-wave function in eyes infected with ΔPil compared to that of eyes infected with ATCC 14579 at each time point, this difference was not statistically significant (P≥0.29).

Figure 3. Retinal function of eyes infected with piliated or nonpiliated B. cereus.

Eyes of C57BL/6J mice were infected with 100 CFU of B. cereus ATCC 14579 (WT) or its isogenic pilus-deficient mutant (ΔPil). Retinal function was assessed by electroretinography at 6, 9, and 12 h postinfection. (A) In general, retinal function declined in all infected eyes by 12 h postinfection. Although there was an observed trend of higher retained A-wave and B-wave function in eyes infected with ΔPil compared to that of eyes infected with WT at each time point, these differences were not statistically significant (P≥0.29). Values represent mean ± SEM of N≥6 eyes each time point. (B) Representative waveforms of eyes infected with WT and ΔPil B. cereus and uninfected contralateral eyes at 12 h postinfection.

3.3. Ocular Pathology

Pathologic changes resulting from intraocular infection with B. cereus ATCC 14579 and ΔPil are depicted in Figure 4. At 3 h postinfection, eyes infected with each strain presented with fibrin infiltrate into the anterior chamber and posterior segments. Corneas were clear, retinas were intact, and retinal layers were distinguishable at this time. B. cereus were noted in the vitreous of eyes infected with both strains. At 6 h postinfection, significant fibrin and infiltrating cells were visible in the anterior segments of eyes infected with each strain. B. cereus were noted in the mid-vitreous and along the inner limiting membrane (Figure 4B), as well as along the posterior capsule and near the ciliary body in eyes infected with either strain. Corneas were slightly edematous, but retinal layers in these infected eyes remained intact. By 9 h postinfection, there was significant inflammation in the anterior and posterior segments of eyes infected with each strain. In addition to the areas described at 6 h, B. cereus were also noted in the anterior chamber of eyes infected with either strain (Figure 4B). Retinal detachments were present in approximately half of eyes from each infection group, but generally, retinal layers remained intact. By 12 h postinfection, all eyes infected with B. cereus ATCC 14579 and ΔPil exhibited severe inflammation, with significant corneal edema, anterior and posterior segment infiltration, and fully detached retinas with indistinguishable retinal layers. B. cereus organisms were noted in the same areas as described for 9 h postinfection. In summary, the gross pathological changes developing in eyes infected with B. cereus ATCC 14579 and ΔPil were indistinguishable from one another.

Figure 4. Retinal damage and intraocular inflammation in eyes infected with piliated or nonpiliated B. cereus.

Eyes of C57BL/6J mice were infected with 100 CFU of B. cereus ATCC 14579 (WT) or its isogenic pilus-deficient mutant (ΔPil). Infected globes were harvested at 3, 6, 9, and 12 h postinfection and processed for hematoxylin and eosin staining. Uninfected C57BL/6J eyes had no inflammation and were architecturally and morphologically similar. At 3 h postinfection, eyes infected with each strain had fibrin infiltrate in the anterior chamber and posterior segments. Corneas were clear, retinas were intact, and retinal layers were distinguishable at this time. B. cereus were noted in the vitreous of eyes infected with both strains. At 6 and 9 h postinfection, significant fibrin and infiltrating cells were visible in the anterior segments of eyes infected with each strain. B. cereus were noted in the mid-vitreous, as well as along the posterior capsule and near the ciliary body in eyes infected with both strains. Retinal layers in these infected eyes remained intact. At 9 h postinfection, B. cereus were also noted in the anterior chamber of eyes infected with either strain. By 12 h postinfection, all infected eyes had severe inflammation, anterior and posterior segment infiltration, and fully detached retinas. B. cereus were noted in the same areas as described for 9 h postinfection. The gross pathological changes developing in eyes infected with each strain were indistinguishable from one another. Sections are representative of three eyes per time point. B. cereus are denoted by white arrows in the higher magnification images in 4B. In 4B: Ret, retina; Vit, vitreous; AqH, aqueous humor; Ir, iris; L, lens. Magnification in A, 10×. Magnification in B, 40×.

Taken together, these results suggest that the growth of nonpiliated B. cereus may have been better controlled during the early stages of intraocular infection, but not to the extent that it significantly altered the decline of retinal function, the development of damaging inflammation, or the migration of B. cereus within the eye.

4. Discussion

Up to two-thirds of eyes intraocularly infected with B. cereus lose significant vision, experiencing severe retinal damage and inflammation that may also result in loss of the eye. The unique virulence of B. cereus in the eye is attributed to a dangerous combination of rapid replication, migration throughout the eye, toxin production, and a resulting robust inflammatory response. Efforts to treat this blinding disease rely on identifying bacterial and host targets that can be exploited to significantly alter the outcome of infection and prevent vision loss.

Pili are proteinaceous appendages on the bacterial surface that perform a myriad of functions related to virulence. Pili on the surface of Gram-positive bacteria are comprised of covalently-linked pilin subunits which are anchored to the cell wall by a sortase/transpeptidase enzyme. The link between pili and the virulence of Gram-negative bacteria has been widely reported, as has the role of fimbrae in the attachment and virulence of both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. For the eye, the corneal virulence of nonpiliated Pseudomonas was highly attenuated, but attenuation was strain dependent (Alarcon et al., 2009, Hazlett et al., 1991, and Zolfgahar et al., 2003). A recent report also highlighted an association between greater production of fimbrae, which are pili-like adhesion appendages, and increased severity of Pseudomonas corneal ulcers (Hammond et al., 2016), so it is reasonable to hypothesize that pili/fimbrae may be involved in bacterial ocular virulence. Since the first report of the presence pili in Corynebacterium (Yanagawa et al., 1968) and the subsequent dissection of pathways involved in pili assembly in Corynebacterium (Ton-That and Schneewind, 2003) and other Gram-positive pathogens (Budzik et al., 2008, Dramsi et al., 2006, Falker et al., 2008, Kline et al., 2009, Lazzarin et al., 2015, LeMieux et al., 2008, Mazmanian et al., 2001, Okura et al., 2011, and Ton-That and Schneewind, 2004), including B. cereus (Budzik et al., 2007, 2008, and 2009a), the importance of pili to bacterial virulence and its potential as a vaccine target has become more appreciated.

Adhesins, including pili and fimbrae, are found on the surface of a number of Gram-positive ocular pathogens, including Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Enterococcus faecalis, and B. cereus. S. aureus adhesins contribute to virulence in a number of infection models (Heilmann 2011), but the presence or importance of pili for this pathogen in the eye has not been determined. S. pneumoniae possesses at least two types of pili which promote in vivo virulence and interact with the host immune response (Bagnoli et al., 2008, Barrochi et al., 2006, and Nelson et al., 2007), but a role for pili in S. pneumoniae eye infections has not been ascribed. Similarly, E. faecalis pili have not been investigated in the context of eye infections, but their role in the pathogenicity of endocarditis and urinary tract infections and the formation of biofilms has been reported (Nallapareddy et al, 2006, Pinkston et al., 2014, and Sillanpaa et al, 2013). To our knowledge, this is the first analysis of the role of B. cereus pili in mammalian infection, including infection of the eye.

Our results demonstrated that during experimental endophthalmitis, B. cereus with pili grew to a greater intraocular burden than B. cereus without pili. Although these strains replicated at similar rates in vitro, the intraocular growth of pili-deficient B. cereus was significantly less compared to that of wild type B. cereus from 3-12 h postinfection. These results suggested that the growth of pili-deficient B. cereus in the eye may have been better controlled during the course of infection. Experimental endophthalmitis initiated by B. cereus deficient in hemolysin BL (Callegan et al., 1999), phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (Callegan et al., 2002), phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C (Callegan et al., 2002), quorum sensing (Callegan et al., 2003), or swarming (Callegan et al., 2006) were not controlled to the same degree as observed with pili-deficient B. cereus. Studies reported that the presence of pili enhanced the uptake of pneumococci and lactobacilli by macrophages (Orrskog et al., 2012 and Vargas Garcia et al., 2015). If this were the case in our model, one would expect the bacterial burden to be greater in eyes infected with pili-deficient B. cereus. However, uptake and killing of Group B streptococci by macrophages was reported to occur regardless of the presence or absence of pili (Papasergi et al., 2011), suggesting that pili-macrophage interactions may be species-dependent. Macrophages and monocytes comprised <5% of cells infiltrating into the eye during B. cereus endophthalmitis (Ramadan et al., 2006), so the interactions of these cells with B. cereus would likely not impact bacterial burden.

Polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN) are the primary infiltrating cell type recruited to the site of infection during B. cereus endophthalmitis (Ramadan et al., 2006). The majority of studies on pili and neutrophil function have involved Gram-negative bacteria such as Neisseria, E. coli, and Moraxella. Pili-deficient mutants of Neisseria gonorrhea were killed more readily by PMN than piliated strains (McNeil and Virgi, 1997 and Stohl et al., 2013). Also, the interaction of this organism directly with the uropods of PMN was pili-dependent (Soderholm et al., 2011). In experimental endophthalmitis, the pili-deficient B. cereus burden was lower than that of the pili-containing B. cereus burden, suggesting that the latter strain was better controlled by the intraocular immune response. Conversely, Moraxella-containing pili were cleared from a mouse otitis media model more readily than pili-deficient strains (Kawano et al., 2013). It has also been suggested that pili-deficient bacteria escape phagocytosis because they are less adherent. This apparently did not occur in our endophthalmitis model, as pili-containing B. cereus grew better in the eye than pili-deficient B. cereus, suggesting that any neutrophil interaction with pili on the surface of B. cereus may have had little effect on clearance or that pili protected B. cereus from interaction with neutrophils.

We reported that TLR2 and TLR4 are important in the severe intraocular inflammation observed during B. cereus endophthalmitis (Novosad et al., 2012 and Parkunan et al, 2015). TLR2 is also important in mediating inflammation in Staphylococcus aureus endophthalmitis (Kochan et al., 2012 and Talreja et al., 2015). We do not know whether the pili of Bacillus interact with these innate immune receptors and are, in fact, TLR ligands. Bassett et al. (2013) reported that inflammatory responses to the RgrA pneumococcal pilus type 1 protein were mediated by TLR2. Fimbriae have also been reported to activate TLR2 in the context of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Salmonella enterica virulence (Hajishengallis et al, 2009, Tukel et al., 2005, and Wang et al., 2007). Further studies showed that the initial inflammatory response to P. gingivalis in macrophages required cooperative signaling of TLR2 and TLR4 (Davey et al, 2008 and Papadopoulos et al., 2013). Reports on the activation of TLR4 by adhesins have primarily involved the FimH adhesin of type 1 fimbrae in Gram-negative bacteria (Abdul-Careem et al., 2011, Fischer et al., 2006, Hedlund et al., 2001, and Mossman et al., 2008). Whether B. cereus pili serve as a TLR ligand is an open question.

Our results demonstrated that the absence of pili resulted in a lower bacterial burden and a trend of less retinal function loss in eyes infected with the pili-deficient mutant. Retinal function loss in B. cereus endophthalmitis is, in part, directly proportional to the number of organisms in the eye in wild type mice (Ramadan et al., 2006), so a lower intraocular bacterial burden should have resulted in a greater degree of retained retinal function. Logically, local toxin production would be decreased in an environment with a lower bacterial burden. However, it is only when B. cereus are quorum sensing-deficient (Callegan et al., 2003 and Callegan et al., 2005) or motility-deficient (Callegan et al., 2005 and Callegan et al., 2006) or mice are immunodeficient (Novosad et al., 2012, Parkunan et al., 2015, and Parkunan et al., 2016) that we have noted stark contrasts in infection severity with equivalent bacterial numbers in control and experimental groups. Taken together, these results highlight the sensitivity of the eye to B. cereus burden and the importance of infection control during its earliest stages.

Tsilia et al. (2015) analyzed the adhesion of pathogenic B. cereus to synthetic intestinal mucin, and suggested that adhesion may contribute to virulence by providing close contact to nutrient sources. While the authors reported that extensive attachment to mucin was not required for virulence, adhesion may provide a stable surface for growth and disruption of the protective mucin layer. Although the role of pili in this scenario was not examined, in the posterior segment, pili or fimbrae of any organism could effectively adhere to intraocular tissues or surfaces of intraocular lenses or suture material, making these infections more difficult to treat. This is an interesting concept to consider in the context of non-motile piliated Gram-positive ocular pathogens such as S. aureus, streptococci, or Enterococcus (Bagnoli et al., 2008, Barocchi et al., 2006, Heilmann 2011, Nallapareddy et al., 2006, Nelson et al., 2007, Pinkston et al., 2014, and Sillanpaa et al., 2013). Indeed, Jett et al. (1998) reported that the localization of E. faecalis to distinct tissues in the eyes of rabbits was likely due to adhesins other than aggregation substance, but this study did not examine pili. For B. cereus, migration throughout the eye occurs within hours of infection (Callegan et al., 1999), suggesting that adhesion may not be an important phenotype in the early stages of this disease.

5. Conclusions

Our findings suggested a potential role for pili in protecting B. cereus from early intraocular clearance, potentially contributing to its virulence during the early stages of endophthalmitis. The growth of nonpiliated B. cereus may have been better controlled during the early stages of intraocular infection, leading to lower numbers of B. cereus and greater retinal function in infected eyes. These data underscore the importance of early infection control. Left untreated, however, infections with piliated and nonpiliated B. cereus resulted in significant vision loss, suggesting that other factors are involved in virulence to a more significant degree. The pathogenicity of B. cereus endophthalmitis is multifactorial, and because of its explosively blinding course, the identification of bacterial and host factors which do and do not contribute to disease pathogenesis is critical in formulating plausible strategies for preventing blindness.

Highlights.

Bacillus cereus endophthalmitis is a potentially blinding intraocular infection.

The hypothesis that B. cereus pili contributed to intraocular virulence was tested.

Intraocular growth of pilus-deficient B. cereus was better controlled.

Results suggest a role for pili in protecting B. cereus from intraocular clearance.

Acknowledgments

This study was presented in part at the 8th International Conference on Gram-Positive Microorganisms/18th International Conference on Bacilli, June 2015. The authors thank Nanette Wheatley, Dr. Feng Li, and Mark Dittmar (OUHSC Live Animal Imaging Core) for their invaluable technical assistance and Excalibur Pathology (Moore, OK) and the OUHSC Cellular Imaging Core for histology expertise. The authors also thank the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation Electron Microscopy Core for assistance with TEM.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01EY024140 (to MCC). Work in Dr. Schneewind's laboratory is supported by R01AI069227. Dr. Callegan's research is also supported in part by NIH grants R01EY025947 (to MCC), R21EY022466 (to MCC), CORE Grant P30EY027125 (to Robert E. Anderson, OUHSC), a Presbyterian Health Foundation Equipment Grant (to Robert E. Anderson, OUHSC), and an unrestricted grant to the Dean A. McGee Eye Institute from Research to Prevent Blindness.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abdul-Careem MF, Firoz Mian M, Gillgrass AE, Chenoweth MJ, Barra NG, Chan T, Al-Garawi AA, Chew MV, Yue G, van Roojen N, Xing Z, Ashkar AA. FimH, a TLR4 ligand, induces innate antiviral responses in the lung leading to protection against lethal influenza infection in mice. Antiviral Res. 2011;92:346–355. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarcon I, Evans DJ, Fleiszig SM. The role of twitching motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa exit from and translocation of corneal epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:2237–44. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astley RA, Coburn PS, Parkunan SM, Callegan MC. Modeling intraocular bacterial infections. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2016;54:30–48. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axner O, Andersson M, Björnham O, Castelain M, Klinth J, Koutris E, Schedin S. Assessing bacterial adhesion on an individual adhesin and single pili level using optical tweezers. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;715:301–313. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0940-9_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagnoli F, Moschioni M, Donati C, Dimitrovska V, Ferlenghi I, Facciotti C, Muzzi A, Giusti F, Emolo C, Sinisi A, Hilleringmann M, Pansegrau W, Censini S, Rappuoli R, Covacci A, Masignani V, Barocchi MA. A second pilus type in Streptococcus pneumoniae is prevalent in emerging serotypes and mediates adhesion to host cells. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:5480–5492. doi: 10.1128/JB.00384-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barocchi MA, Ries J, Zogaj X, Hemsley C, Albiger B, Kanth A, Dahlberg S, Fernebro J, Moschioni M, Masignani V, Hultenby K, Taddei AR, Beiter K, Wartha F, von Euler A, Covacci A, Holden DW, Normark S, Rappuoli R, Henriques-Normark B. A pneumococcal pilus influences virulence and host inflammatory responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2857–2862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511017103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basset A, Zhang F, Benes C, Sayeed S, Herd M, Thompson C, Golenbock DT, Camilli A, Malley R. Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 mediates inflammatory responses to oligomerized RrgA pneumococcal pilus type 1 protein. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:2665–2675. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.398875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budzik JM, Marraffini LA, Schneewind O. Assembly of pili on the surface of Bacillus cereus vegetative cells. Mol Microbiol. 2007;66:495–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budzik JM, Marraffini LA, Souda P, Whitelegge JP, Faull KF, Schneewind O. Amide bonds assemble pili on the surface of bacilli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10215–10220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803565105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budzik JM, Oh SY, Schneewind O. Cell wall anchor structure of BcpA pili in Bacillus anthracis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:36676–36686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806796200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budzik JM, Oh SY, Schneewind O. Sortase D forms the covalent bond that links BcpB to the tip of Bacillus cereus pili. J Biol Chem. 2009a;284:12989–12997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900927200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budzik JM, Poor CB, Faull KF, Whitelegge JP, He C, Schneewind O. Intramolecular amide bonds stabilize pili on the surface of bacilli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009b;106:19992–19997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910887106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callegan MC, Booth MC, Jett BD, Gilmore MS. Pathogenesis of Gram-positive bacterial endophthalmitis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3348–3356. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3348-3356.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callegan MC, Cochran DC, Kane ST, Gilmore MS, Gominet M, Lereclus D. Contribution of membrane-damaging toxins to Bacillus endophthalmitis pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2002;70:5381–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.10.5381-5389.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callegan MC, Gilmore MS, Gregory M, et al. Bacterial endophthalmitis: Therapeutic challenges and host-pathogen interactions. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2007;26:189–203. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callegan MC, Jett BD, Hancock LE, Gilmore MS. Role of hemolysin BL in the pathogenesis of extraintestinal Bacillus cereus infection assessed in an endophthalmitis model. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3357–66. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3357-3366.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callegan MC, Kane ST, Cochran DC, Gilmore MS, Gominet M, Lereclus D. Relationship of plcR-regulated factors to Bacillus endophthalmitis virulence. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3116–3124. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3116-3124.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callegan MC, Kane ST, Cochran DC, Novosad B, Gilmore MS, Gominet M, Lereclus D. Bacillus endophthalmitis: Roles of bacterial toxins and motility during infection. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:3233–3238. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callegan MC, Novosad BD, Ramirez R, Ghelardi E, Senesi S. Role of swarming migration in the pathogenesis of Bacillus endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:4461–4467. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan WM, Liu DT, Chan CK, Chong KK, Lam DS. Infective endophthalmitis caused by Bacillus cereus after cataract extraction surgery. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:e31–e34. doi: 10.1086/375898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JC, Roy M. Epidemic Bacillus endophthalmitis after cataract surgery II: Chronic and recurrent presentation and outcome. Ophthalmol. 2000;107:1038–1041. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00099-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CL, Jr, Madden WM, Hatem GF, Merritt JC. Endogenous Bacillus cereus panophthalmitis. Ann Ophthalmol. 1997;19:65–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crotty Alexander LE, Maisey HC, Timmer AM, Rooijakkers SH, Gallo RL, von Köckritz-Blickwede M, Nizet V. M1T1 group A streptococcal pili promote epithelial colonization but diminish systemic virulence through neutrophil extracellular entrapment. J Mol Med (Berl) 2010;88:371–381. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0566-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danne C, Dramsi S. Pili of gram-positive bacteria: Roles in host colonization. Res Microbiol. 2012;163:645–658. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey M, Liu X, Ukai T, Jain V, Gudino C, Gibson FC, 3rd, Golenbock D, Visintin A, Genco CA. Bacterial fimbriae stimulate proinflammatory activation in the endothelium through distinct TLRs. J Immunol. 2008;180:2187–2195. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David D, Kirkby GR, Noble BA. Bacillus cereus endophthalmitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1994;78:577–580. doi: 10.1136/bjo.78.7.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dramsi S, Caliot E, Bonne I, Guadagnini S, Prévost MC, Kojadinovic M, Lalioui L, Poyart C, Trieu-Cuot P. Assembly and role of pili in group B streptococci. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:1401–1413. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fälker S, Nelson AL, Morfeldt E, Jonas K, Hultenby K, Ries J, Melefors O, Normark S, Henriques-Normark B. Sortase-mediated assembly and surface topology of adhesive pneumococcal pili. Mol Microbiol. 2008;70:595–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06396.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer H, Yamamoto M, Akira S, Beutler B, Svanborg C. Mechanism of pathogen-specific TLR4 activation in the mucosa: Fimbriae, recognition receptors and adaptor protein selection. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:267–277. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Wang M, Liang S. Induction of distinct TLR2-mediated proinflammatory and proadhesive signaling pathways in response to Porphyromonas gingivalis fimbriae. J Immunol. 2009;182:6690–6696. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond JH, Hebert WP, Naimie A, Ray K, Van Gelder RD, DiGiandomenico A, Lalitha P, Srinivasan M, Acharya NR, Lietman T, Hogan DA, Zegans ME. Environmentally endemic Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains with mutations in lasR are associated with increased disease severity in corneal ulcers. mSphere. 2016;1:e00140–16. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00140-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazlett LD, Moon MM, Singh A, Berk RS, Rudner XL. Analysis of adhesion, piliation, protease production and ocular infectivity of several P. aeruginosa strains. Curr Eye Res. 1991;10:351–62. doi: 10.3109/02713689108996341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedlund M, Frendéus B, Wachtler C, Hang L, Fischer H, Svanborg C. Type 1 fimbriae deliver an LPS- and TLR4-dependent activation signal to CD14-negative cells. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39:542–552. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilmann C. Adhesion mechanisms of staphylococci. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;715:105–123. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0940-9_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jett BD1, Atkuri RV, Gilmore MS. Enterococcus faecalis localization in experimental endophthalmitis: Role of plasmid-encoded aggregation substance. Infect Immun. 1998;66:843–848. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.843-848.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano T, Hirano T, Kodama S, Mitsui MT, Ahmed K, Nishizono A, Suzuki M. Pili play an important role in enhancing the bacterial clearance from the middle ear in a mouse model of acute otitis media with Moraxella catarrhalis. Pathog Dis. 2013;67:119–131. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline KA, Kau AL, Chen SL, Lim A, Pinkner JS, Rosch J, Nallapareddy SR, Murray BE, Henriques-Normark B, Beatty W, Caparon MG, Hultgren SJ. Mechanism for sortase localization and the role of sortase localization in efficient pilus assembly in Enterococcus faecalis. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:3237–3247. doi: 10.1128/JB.01837-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochan T, Singla A, Tosi J, Kumar A. Toll-like receptor 2 ligand pretreatment attenuates retinal microglial inflammatory response but enhances phagocytic activity toward Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 2012;80:2076–2088. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00149-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzarin M, Cozzi R, Malito E, Martinelli M, D'Onofrio M, Maione D, Margarit I, Rinaudo CD. Noncanonical sortase-mediated assembly of pilus type 2b in group B Streptococcus. FASEB J. 2015;29:4629–4640. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-272500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeMieux J, Woody S, Camilli A. Roles of the sortases of Streptococcus pneumonia in assembly of the RlrA pilus. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:6002–6013. doi: 10.1128/JB.00379-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandlik A, Swierczynski A, Das A, Ton-That H. Pili in Gram-positive bacteria: Assembly, involvement in colonization and biofilm development. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazmanian SK, Ton-That H, Schneewind O. Sortase-catalysed anchoring of surface proteins to the cell wall of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:1049–1057. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil G, Virji M. Phenotypic variants of meningococci and their potential in phagocytic interactions: the influence of opacity proteins, pili, PilC and surface sialic acids. Microb Pathog. 1997;22:295–304. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melville S, Craig L. Type IV pili in Gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2013;77:323–341. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00063-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossman KL, Mian MF, Lauzon NM, Gyles CL, Lichty B, Mackenzie R, Gill N, Ashkar AA. Cutting edge: FimH adhesin of type 1 fimbriae is a novel TLR4 ligand. J Immunol. 2008;181:6702–6706. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.6702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer AL, Ramadan RT, Novosad BD, Astley R, Callegan MC. Bacillus cereus-induced permeability of the blood-ocular barrier during experimental endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:3783–3793. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nallapareddy SR, Singh KV, Sillanpää J, Garsin DA, Höök M, Erlandsen SL, Murray BE. Endocarditis and biofilm-associated pili of Enterococcus faecalis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2799–2807. doi: 10.1172/JCI29021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson AL, Ries J, Bagnoli F, Dahlberg S, Fälker S, Rounioja S, Tschöp J, Morfeldt E, Ferlenghi I, Hilleringmann M, Holden DW, Rappuoli R, Normark S, Barocchi MA, Henriques-Normark B. RrgA is a pilus-associated adhesin in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 2007;66:329–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05908.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novosad BD, Astley RA, Callegan MC. Role of Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 in experimental Bacillus cereus endophthalmitis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28619. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Day DM, Smith RS, Gregg CR, Turnbull PC, Head WS, Ives JA, Ho PC. The problem of Bacillus species infection with special emphasis on the virulence of Bacillus cereus. Ophthalmol. 1981;88:833–838. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(81)34960-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okura M, Osaki M, Fittipaldi N, Gottschalk M, Sekizaki T, Takamatsu D. The minor pilin subunit Sgp2 is necessary for assembly of the pilus encoded by the srtG cluster of Streptococcus suis. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:822–831. doi: 10.1128/JB.01555-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orrskog S, Rounioja S, Spadafina T, Gallotta M, Norman M, Hentrich K, Fälker S, Ygberg-Eriksson S, Hasenberg M, Johansson B, Uotila LM, Gahmberg CG, Barocchi M, Gunzer M, Normark S, Henriques-Normark B. Pilus adhesin RrgA interacts with complement receptor 3, thereby affecting macrophage function and systemic pneumococcal disease. MBio. 2012;4(1):e00535–12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00535-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos G, Weinberg EO, Massari P, Gibson FC, 3rd, Wetzler LM, Morgan EF, Genco CA. Macrophage-specific TLR2 signaling mediates pathogen-induced TNF-dependent inflammatory oral bone loss. J Immunol. 2013;190:1148–1157. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papasergi S, Brega S, Mistou MY, Firon A, Oxaran V, Dover R, Teti G, Shai Y, Trieu-Cuot P, Dramsi S. The GBS PI-2a pilus is required for virulence in mice neonates. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18747. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkunan SM, Astley R, Callegan MC. Role of TLR5 and Flagella in Bacillus Intraocular Infection. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100543. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkunan SM, Randall CB, Astley RA, Furtado GC, Lira SA, Callegan MC. CXCL1, but not IL-6, significantly impacts intraocular inflammation during infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2016;100:1125–1134. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3A0416-173R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkunan SM, Randall CB, Coburn PS, Astley RA, Staats RL, Callegan MC. Unexpected Roles for Toll-Like Receptor 4 and TRIF in Intraocular Infection with Gram-Positive Bacteria. Infect Immun. 2015;83:3926–3936. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00502-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkston KL, Singh KV, Gao P, Wilganowski N, Robinson H, Ghosh S, Azhdarinia A, Sevick-Muraca EM, Murray BE, Harvey BR. Targeting pili in enterococcal pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2014;82:1540–1547. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01403-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadan RT, Moyer AL, Callegan MC. A role for tumor necrosis factor-alpha in experimental Bacillus cereus endophthalmitis pathogenesis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:4482–4489. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadan RT, Ramirez R, Novosad BD, Callegan MC. Acute inflammation and loss of retinal architecture and function during experimental Bacillus endophthalmitis. Curr Eye Res. 2006;31:955–965. doi: 10.1080/02713680600976925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero D. Bacterial determinants of the social behavior of Bacillus subtilis. Res Microbiol. 2013;164:788–798. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy M, Chen JC, Miller M, Boyaner D, Kasner O, Edelstein E. Epidemic Bacillus endophthalmitis after cataract surgery I: Acute presentation and outcome. Ophthalmol. 1997;104:1768–1772. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadaka A, Durand ML, Gilmore MS. Bacterial endophthalmitis in the age of outpatient intravitreal therapies and cataract surgeries: host-microbe interactions in intraocular infection. Prog Ret Eye Res. 2012;31:316–331. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneewind O, Missiakas DM. Protein secretion and surface display in Gram-positive bacteria. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2012;367:1123–1139. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillanpää J, Chang C, Singh KV, Montealegre MC, Nallapareddy SR, Harvey BR, Ton-That H, Murray BE. Contribution of individual Ebp Pilus subunits of Enterococcus faecalis OG1RF to pilus biogenesis, biofilm formation and urinary tract infection. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68813. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söderholm N, Vielfort K, Hultenby K, Aro H. Pathogenic Neisseria hitchhike on the uropod of human neutrophils. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stohl EA, Dale EM, Criss AK, Seifert HS. Neisseria gonorrhoeae metalloprotease NGO1686 is required for full piliation, and piliation is required for resistance to H2O2- and neutrophil-mediated killing. MBio. 2013;4:e00399–13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00399-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talreja D, Singh PK, Kumar A. In Vivo Role of TLR2 and MyD88 Signaling in Eliciting Innate Immune Responses in Staphylococcal Endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:1719–1732. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-16087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ton-That H, Schneewind O. Assembly of pili on the surface of C. diphtheriae. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:1429–1438. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ton-That H, Schneewind O. Assembly of pili in Gram-positive bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:228–234. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsilia V, Uyttendaele M, Kerckhof FM, Rajkovic A, Heyndrickx M, Van de Wiele T. Bacillus cereus Adhesion to Simulated Intestinal Mucus Is Determined by Its Growth on Mucin, Rather Than Intestinal Environmental Parameters. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2015;12:904–913. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2014.1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tükel C, Raffatellu M, Humphries AD, Wilson RP, Andrews-Polymenis HL, Gull T, Figueiredo JF, Wong MH, Michelsen KS, Akçelik M, Adams LG, Bäumler AJ. CsgA is a pathogen-associated molecular pattern of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium that is recognized by Toll-like receptor 2. Mol Microbiol. 2005;58:289–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas García CE, Petrova M, Claes IJ, De Boeck I, Verhoeven TL, Dilissen E, von Ossowski I, Palva A, Bullens DM, Vanderleyden J, Lebeer S. Piliation of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG promotes adhesion, phagocytosis, and cytokine modulation in macrophages. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:2050–2062. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03949-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vengadesan K, Narayana SV. Structural biology of Gram-positive bacterial adhesins. Protein Sci. 2011;20:759–772. doi: 10.1002/pro.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagawa R, Otsuki K, Tokui T. Electron microscopy of fine structure of Corynebacterium renale with special reference to pili. Jpn J Vet Res. 1968;16:31–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Shakhatreh MA, James D, Liang S, Nishiyama S, Yoshimura F, Demuth DR, Hajishengallis G. Fimbrial proteins of Porphyromonas gingivalis mediate in vivo virulence and exploit TLR2 and complement receptor 3 to persist in macrophages. J Immunol. 2007;179:2349–2358. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolfgahar I, Evans DJ, Fleiszig SM. Twitching motility contributes to the role of pili in corneal infection caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun. 2003;71:5389–93. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.9.5389-5393.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]