Abstract

Objective

Patients often anticipate cure from palliative chemotherapy. Better resources are needed to convey its risks and benefits. We describe the stakeholder-driven development and acceptability testing of a prototype video and companion booklet supporting informed consent (IC) for a common palliative chemotherapy regimen.

Methods

Our multidisciplinary team (researchers, advocates, clinicians) employed a multistep process of content development, production, critical evaluation, and iterative revisions. Patient/clinician stakeholders were engaged throughout using stakeholder advisory panels, featuring their voices within the intervention, conducting surveys and qualitative interviews. A national panel of 57 patient advocates, and 25 oncologists from nine US practices critiqued the intervention and rated its clarity, accuracy, balance, tone, and utility. Participants also reported satisfaction with existing chemotherapy IC materials.

Results

Few oncologists (5/25, 20%) or advocates (10/22, 45%) were satisfied with existing IC materials. In contrast, most rated our intervention highly, with 89–96% agreeing it would be useful and promote informed decisions. Patient voices were considered a key strength. Every oncologist indicated they would use the intervention regularly.

Conclusion

Our intervention was acceptable to advocates and oncologists. A randomized trial is evaluating its impact on the chemotherapy IC process.

Practice Implications

Stakeholder-driven methods can be valuable for developing patient educational interventions.

Keywords: cancer chemotherapy, informed consent, palliative care, prognosis communication, video intervention, patient-centered communication

1. INTRODUCTION

Informing patients about the risks and benefits of their cancer treatment options is a cornerstone of quality, patient-centered care [1,2]. Oncology practices therefore require documentation of informed consent (IC) before chemotherapy administration [3], a practice upheld by ASCO’s Quality Oncology Practice Initiative[4]. Unfortunately, the IC process is failing to achieve its purpose [5] - particularly in the palliative setting[6–9]. Patients with metastatic cancer commonly anticipate cure from chemotherapy [7,8,10] or grossly overestimate its benefits [9,11]. For example, in the CanCORS study 81% of patients receiving chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) failed to respond that cure was not at all likely [8]. These misconceptions undermine patients’ ability to plan for the future and may negatively impact care at end of life [12–14].

Communication gaps during IC likely contribute to misconceptions.[15] To establish rapport and promote hope oncologists may de-emphasize [5,16] the limitations of palliative chemotherapy or avoid explicit discussion. Potential benefits of chemotherapy (e.g. on disease control or life expectancy) and are infrequently disclosed [12,15–17] although most patients want this information [18,19]. Furthermore, patients are often overwhelmed during IC discussions, which may hinder recall or make them particularly vulnerable to misinterpretations.

Materials available to support IC do little to fill these gaps. IC documents and educational materials focus almost exclusively on side effects [5,20], with little attention to potential benefits, typical experiences, or patient-centered concerns. Chemotherapy educational materials are more fundamentally limited because they are usually organized around individual drugs rather than regimens. This approach poorly conveys the totality of the chemotherapy experience, and gives patients little sense of what lies ahead. Given its integral place in cancer care, the IC process is an ideal target for interventions to enhance patients’ knowledge and empower value-consistent care decisions.

There has been increasing recognition that involving patients and other stakeholders in research can enhance its quality and relevance [21]. We hypothesized that the chemotherapy IC process could be substantially improved by partnering with patients, caregivers, and clinicians. Although stakeholder-driven research has grown tremendously due to initiatives of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI)[21] and other agencies [22] published reports to guide stakeholder engagement in the development of patient educational interventions are few [22–24].

Stakeholders can be defined as persons with experiential knowledge of a condition, including patients, caregivers, and clinicians.[24] Such persons can be particularly valuable partners in the development of patient educational interventions or decision-support tools, because their practical knowledge can help researchers better understand and meet the needs of their target population. Although best practice guidelines recommend patient involvement in intervention development,[25,26] patient stakeholders are commonly relegated to narrow or short-term project roles that offer limited opportunities to impact project outcomes[24,27]. Furthermore, published experiences often include cursory descriptions of stakeholder engagement methods, and infrequently analyze its impact on the research process. More robust stakeholder engagement efforts, and fuller analyses of these experiences are needed [21,27]. Here, we describe our experiences leading a stakeholder-driven development and critical evaluation of a patient-centered intervention to support IC for palliative chemotherapy.

2. METHODS

2.1. Intervention framework

Video interventions have been shown to enhance knowledge and influence patient preferences regarding sensitive topics such as advance care planning and clinical trial participation [28,29]. We therefore chose to create an intervention that harnessed video and written formats to support chemotherapy IC. Specifically, we created a suite of regimen-specific chemotherapy IC videos and companion booklets explaining guideline-recommended treatment options for metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) [30]. We sought to further improve upon existing chemotherapy educational resources by organizing the intervention by regimen rather than individual drugs, balancing attention to risks and potential benefits, and by featuring the voices of authentic clinicians and patients (e.g. video clips of patients sharing chemotherapy experiences). Content was focused on core domains of IC (benefits, risks, and alternatives) [31], and topics relevant to treatment (e.g. logistics of chemotherapy administration). This work was funded by PCORI (CE-1304-6517), without industry involvement.

2.2. Overview of study processes

Figure 1 presents a visual overview of the intervention development processes. Our multidisciplinary research team at an academic cancer center partnered with patient, caregiver, and oncology clinician stakeholders to develop a prototype IC intervention for FOLFOX and FOLFOX-bevacizumab (FOLFOX+/−bev), the most common first-line treatments for mCRC in the US [30]. After iterative stakeholder-driven revisions, the prototype underwent acceptability testing by a national panel of patient advocates and a cohort of medical oncologists, followed by stakeholder-driven revisions. Cognitive interviews with mCRC patients guided further intervention refinements, after which our prototype was extended to other regimens. Here we describe the development, critical evaluation, and refinement of our prototype intervention.

Figure 1.

Intervention development and stakeholder engagement

2.3. Approach to stakeholder engagement

Our stakeholder engagement focused on central participants in the chemotherapy IC process [21]: patients, caregivers, oncology physicians and nurses. First we ensured that our multidisciplinary research team included the perspectives of patient advocacy (EF), medical oncology (ACE, DS, NJM), palliative care (ACE), oncology nursing (HC), and health services research (DS, JKW). This group met frequently and shared editorial control over the project. Next we established core panels of patient/caregiver and clinician stakeholders to advise the team and assist throughout the development process. We created numerous other opportunities for stakeholder engagement: mCRC patients and clinicians were filmed within the IC videos; patients contributed quotes to the IC booklets; clinicians and advocates were surveyed; and mCRC patients participated in qualitative interviews.

2.4 Patient/caregiver stakeholder panel

Our local patient/caregiver stakeholder panel included four mCRC patients and two cancer survivors who co-identified as caregivers, recruited from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI). An expert patient stakeholder panel included four patient advocates with leadership experience in national cancer research and advocacy organizations, such as the Colon Cancer Alliance. These panels were oriented to the project during separate kick-off calls. Subsequently our lead patient advocate (EF) liaised with panel members for advice and feedback on various iterations of the intervention using a flexible combination of email, circulation of draft documents, phone calls, and individual meetings. Local stakeholders participated in two additional in-person group meetings (also attended by the core research team) during which they discussed the intervention at critical stages of development.

2.5 Clinician stakeholder panel

Our core clinician panel included five gastrointestinal oncologists, two oncology nurses, two palliative care specialists, and an oncology social worker. Panel members advised the study team and critiqued iterative drafts of the intervention via email, circulation of draft documents, and individual discussions.

2.6. Content Development Phase

The study team first reviewed the literature on FOLFOX+/−bev, and used this evidence base to draft the prototype IC booklet and scripted portions of the IC video. Content was broadly organized into chemotherapy purpose/benefits, infusion process, risks/side effects, impact of bevacizumab, coping and decision-making, and treatment alternatives. We also drafted video and booklet chapters about the impact of FOLFOX+/−bev on life expectancy. These chapters were subjected to extra scrutiny due to their sensitive nature (see critical evaluation). Our study team drafted most of the content because of the significant time and expertise required; however, patient stakeholders drafted select content areas such as a frequently asked questions (FAQ’s) section, which they populated with a list of “things they wish they had known before starting chemotherapy.” Patient stakeholders also drafted material addressing the emotional dimensions of a chemotherapy decision, and created an interview guide used to film mCRC patients. All draft materials were circulated to our core stakeholder panels and were revised iteratively prior to moving to the production phase.

2.7. Production Phase

For the prototype IC booklet, health communication specialists from the DFCI Health Communication Core edited the material to target a 6th–8th grade reading level, and to adhere to best health communication practices [32]. Graphics specialists then created a printed booklet using colors, fonts, call-out boxes, graphics, authentic patient photos and quotes. A professional health videographer filmed several oncologists and an oncology nurse reading scripted material from a teleprompter, and describing similar information in an unscripted fashion. Clinicians were chosen to maximize diversity with respect to age, gender and ethnicity. All clinicians reviewed and edited their script prior to filming. Next several mCRC patients were filmed describing their experiences on FOLFOX+/−bev using an interview guide designed by patient stakeholders to elicit side effects, quality of life, coping, and any benefits derived from treatment. Patients were referred by DFCI clinicians, and selected to reflect socio-demographic diversity, and to capture a typical spectrum of chemotherapy experiences with respect to side effects and treatment outcomes. No professional actors were used. Footage was edited professionally, with intensive input from the study team to ensure its accuracy, clarity and balance.

2.8. Critical Evaluation

Our prototype intervention underwent acceptability testing by 1) a national panel of patient advocates and 2) a cohort of oncology practitioners. After responsive stakeholder-driven revisions, we conducted qualitative interviews with mCRC patients. Protocols for acceptability testing and qualitative interviews were reviewed and approved by the DFCI IRB. Written documentation of informed consent was waived for all participants.

All patient advocates registered to attend the 2014 American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting in Chicago, IL were invited by email to attend an on-site, interactive session. Of 323 advocates invited, 57 actively participated. After an introduction to the project, participants reviewed the prototype video and booklet in their entirety. Using an audience response system, advocates then rated their agreement with a series of items about the clarity of the intervention, its balance, tone, and utility (e.g. “The booklet is well organized and easy to follow”). Responses ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree on a 5-point Likert scale. Additional items assessed the importance of communicating chemotherapy benefits (e.g. “Information about life expectancy is important to most cancer patients”). Participants then assessed the prognosis sections of the booklet and video, and were asked whether they should be retained as core intervention components, made optional (opt-in approach), or removed. Advocates wrote open-ended critiques on a handout and directly on their IC booklet. Finally, JW moderated a 20-minute discussion focused on survey items with low acceptability and on optimal strategies to communicate prognostic information. Notes were taken during the discussion.

A convenience sample of 44 medical oncology physicians and mid-level providers from ten US practices were invited by email to review the intervention online and complete an anonymous e-survey. A total of 25 practitioners from nine sites participated (response rate, 57%). The survey first assessed satisfaction with chemotherapy educational materials used in their current practice. Similar to the advocate survey, practitioners then assessed acceptability of the intervention with a focus on clarity, accuracy, balance, and clinical utility. Practitioners were asked whether the prognosis chapters should be retained in the intervention, removed, or made optional. Finally, they provided open-ended critiques of the IC video and booklet.

2.9. Analyses of acceptability testing

Survey items rated negatively (defined as disagree or strongly disagree) by more than 20% of either cohort were deemed unacceptable and prompted intervention revisions. Pair-wise, chi-square tests determined participants’ preferred approach to the prognosis sections (retain, make optional, or remove). Advocates’ and oncologists’ open-ended critiques were collated. Common critical feedback prompted intervention revisions.

2.10. Stakeholder-driven revisions

Results of acceptability testing were communicated to our core stakeholder panels and discussed during a second in-person patient stakeholder meeting. Stakeholders helped guide intervention revisions in response.

2.11. Qualitative interviews

were conducted with our target population. Eligible patients were over 21 and had received palliative chemotherapy for mCRC. Exclusion criteria included inability to speak, understand or read English, delirium or dementia, or inadequate stamina for the 60-minute interview. Patients were identified by review of DFCI clinic schedules, and approached by EF for participation. Participants first reviewed the revised IC booklet and video, and were led through a semi-structured series of questions assessing their understanding of the material and its acceptability, using standard qualitative interviewing techniques [33]. Interviews were audio-recorded, and notes were taken during and after. Feedback was examined, and common critiques prompted refinements to the intervention.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Prototype Intervention

The final prototype video and booklet can be found at www.chemovideo.org (logon and password: FOLFOX); both are summarized in Table 1. In response to acceptability testing, prognosis sections were retained as optional components of the video and booklet using an “opt-in” format.

Table 1.

Overview of Final Prototype Informed Consent Intervention for FOLFOX+/−bev

| Organization | Core content | Distinguishing features | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IC Video | IC Booklet | ||

| Background |

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Purpose and Benefits |

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Treatment administration |

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Side effects |

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Bevacizumab |

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Coping/making a treatment decision |

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Opt-in section on prognosis |

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Treatment alternatives |

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Frequently Asked Questions | Answers FAQ’s contributed by patient stakeholders | Absent | Present |

The 21-minute video is narrated by six oncologists and one nurse. A social worker offers unscripted advice about coping and addresses the emotional impact of a new diagnosis. An optional web-link allows patients to watch an additional two-minute segment about the impact of chemotherapy on prognosis. Unscripted interviews with five mCRC patients present their perspectives on treatment. Candid patient footage demonstrates the infusion process. Interviews were edited to present a balanced range of experiences and treatment outcomes (including one patient with cancer progression on initial restaging).

The 22-page booklet serves as a reference guide and an alternative resource, allowing patients to access information in their preferred format. Graphics reinforce key concepts, and photographs illustrate the treatment process. Patient-centeredness is augmented through authentic patient quotes, “call-out” boxes answering common questions, and FAQ’s. Side effects are displayed in tabular format, with a column presenting self-management advice. Prognostic information is presented in two opposing pages, sealed and preceded by a cautionary explanation.

Core stakeholder panels substantively shaped the intervention. Video modifications prompted by patient stakeholders include filming a social worker to discuss coping, emphasizing patients’ resilience, and eliminating unnecessarily “scary” side effect descriptions. Patients strongly supported our decision to film authentic patients and clinicians rather than actors; however, clinicians were considered “stiff” on camera. In response we re-filmed clinicians and worked with patients to select the most acceptable footage. With respect to the booklet, patients rephrased sensitive passages, they added a segment about decision-making, and populated FAQ’s. At their suggestion we added phonetic pronunciations, augmented patient photographs, and we solicited quotes about coping and symptom management from patient members of the Colon Cancer Alliance and incorporated these throughout the booklet. Provider stakeholder contributions largely focused on ensuring accuracy and clarity.

3.2. Acceptability testing sample characteristics

Table 2 presents characteristics of the 57 patient advocates and 25 oncology practitioners who participated in acceptability testing. Approximately half of advocates were cancer patients, 12% were caregivers, and 12% co-identified as patient and caregiver. Our practitioner cohort included 22 oncologists and 3 oncology mid-level providers.

Table 2.

Patient advocate and oncology practitioner cohorts participating in acceptability testing

| Sample Characteristic | Patient Advocate Cohort n (%); N=57 |

Practitioner Cohort n (%); N=25 |

|---|---|---|

| Advocacy Perspective | ||

| Cancer patient/survivor | 26 (46) | – |

| Caregiver | 7 (12) | – |

| Both patient and caregiver | 7 (12) | – |

| Neither patient nor caregiver | 16 (28) | – |

| Colorectal cancer primary focus of advocacy work | ||

| Yes | 12 (21) | – |

| No | 45 (79) | – |

| Prior chemotherapy receipt (advocate, or patient for whom the advocate served as caregiver) | ||

| Yes | 35 (61) | – |

| Advanced cancer diagnosis (advocate, or patient for whom the advocate served as caregiver) | ||

| Yes | 28 (49) | – |

| Professional Role | ||

| Medical oncologist | – | 22 (88) |

| Medical oncology mid-level provider | – | 3 (12) |

| Practice Site | ||

| Academic medical center | – | 22 (88) |

| Community practice | – | 3 (12) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 6 (11) | 14 (56) |

| Female | 34 (60) | 11 (44) |

| Age | ||

| ≤39 | 7 (12) | 14 (56) |

| 40–49 | 7 (12) | 4 (16) |

| 50–59 | 13 (26) | 6 (24) |

| 60–69 | 9 (16) | 1 (4) |

| ≥70 | 4 (7) | 0 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 35 (61) | 21 (84) |

| Black | 6 (11) | 1 (4) |

| Asian/other | 1 (2) | 3 (12) |

| Hispanic | 2 (4) | 1 (4) |

| Education | ||

| High school or some college | 2 (4) | – |

| College graduate | 18 (32) | – |

| Graduate or professional degree | 22 (39) | – |

Colum percentages may not add to 100% due to missing data

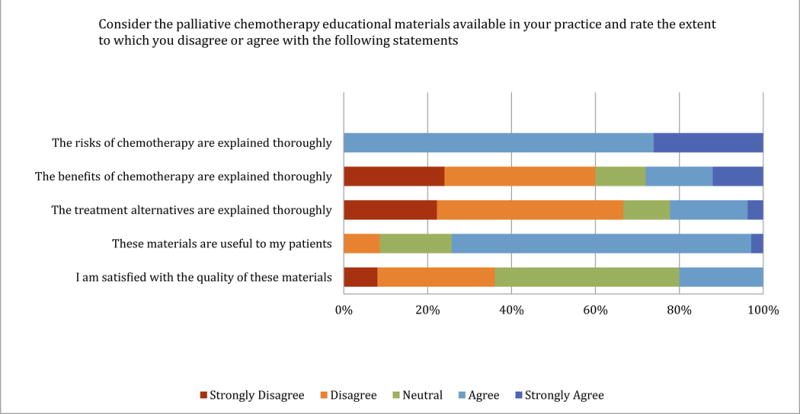

3.3. Perspectives on existing chemotherapy educational materials

Only 20% (5/25) of practitioners were satisfied with the chemotherapy educational materials used in their current practice (Figure 2). Although most agreed that risks were explained thoroughly, few agreed that benefits or treatment alternatives were adequately explained. Among the 22 advocates who recalled previously receiving chemotherapy educational materials, only 45% (10/22) agreed they were useful.

Figure 2.

Practitioner perspectives on chemotherapy educational materials used in current practice (N=25)

3.4. Advocate ratings of intervention

Patient advocates rated the organization, clarity, balance, and tone of the intervention highly (see Figure 3a–c). The vast majority agreed it would be useful and help patients make more informed treatment decisions. All advocates agreed (10/57, 17.5%) or strongly agreed (47/57, 82.5%) that patient voices strengthened the intervention. Two items met our criteria for unacceptable: over 20% of advocates perceived treatment alternatives to be biased (see 3.7. for discussion).

Figure 3.

Patient advocate (N=57) and oncology practitioner ratings (N=25) of prototype informed consent intervention

3.5. Oncologist ratings of intervention

Oncology practitioners rated the intervention highly on every domain (see Figure 3d–f). When asked how often they would distribute the intervention to patients (never, seldom, about half the time, usually or always), 64% (16/25) stated usually and 36% (9/25) always.

3.6. Perspectives on prognostic communication

Most advocates agreed that information about response rates (50/56, 89%) and life expectancy (51/56, 91%) were important to patients. Advocates preferred the video prognosis segment to be accessed by an optional web-link, as compared to making it a core feature or eliminating it from the intervention [39/54 (72%), 14/54 (26%), 1/54 (1.9%) respectively; p<.01 for both comparisons]. Only 8.8% (5/57) thought the prognosis segment would be too upsetting to patients, and 10.5% (6/57) thought it would take away hope. Advocates preferred for the written prognosis segment to be placed at the booklet’s end (24/43, 55.8%) rather than featuring it within its main body (11/43, 25.6%; p=.04) or removing it (8/43, 18.6%; p<.01). In group discussion advocates expressed concern that end-placement might not adequately protect against unwanted prognostic information and suggested sealing this section with a sticker, a solution we ultimately adopted. Similarly, 84% (21/25) of practitioners preferred an optional approach to prognostic communication sections.

3.7. Qualitative evaluations and responsive revisions

Most advocate and practitioner comments were favorable and required no intervention revisions. Several advocates perceived bias in favor of FOLFOX. During group discussion it became clear this was driven by a mistaken impression that the intervention would be distributed to patients independently from an oncologist’s treatment recommendation. To these advocates, the intervention seemed to be an advertisement rather than an educational resource. In response, we followed advocates’ suggestion to more clearly frame FOLFOX as one of several treatment options, and explicitly state our independence from industry. Several patients requested more attention to bevacizumab. Numerous advocates and practitioners criticized clinician footage, and suggested re-filming oncologists looking directly into the camera. Although budgetary constraints did not allow us to re-film our prototype video, these suggestions were enacted for all subsequent videos. Three advocates and one oncologist criticized footage of patients laughing and smiling, suggesting this led to a “rosy” picture of chemotherapy. Although our core stakeholders upheld this as an authentic representation of their experiences, we added more somber segments for balance. Several advocates and oncologists indicated the intervention was too long. We shortened where possible, and added a table of contents to make the booklet easier to navigate. Several participants suggested bolder colors, clarification of palliative care, more patient photographs, and clearer attributions for patient quotes – all of which we adopted.

3.8. Qualitative interviews and intervention refinements

Five mCRC patients were interviewed after reviewing the intervention. Overall the intervention was accurately understood and perceived to be highly useful. Qualitative feedback prompted several phrasing modifications, reconciliation of minor inconsistencies, redesign of the booklet cover, photograph replacements, and a more prominent warning before prognosis information.

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Discussion

The recent ASCO position statement “Toward individualized care for patients with advanced cancer” asserts that “realistic conversations about prognosis, the potential benefits and limitations of disease-directed therapy...occur late in the course of illness or not at all,” and that these omissions impede quality, patient-centered care [2]. Despite critical need, few interventions exist to support these communications. Using stakeholder-driven methods, we developed a dual format video/print based intervention targeting the chemotherapy IC process to offer patients upfront, realistic information about prognosis and palliative chemotherapy outcomes in a patient-centered manner. The resulting intervention was rated highly by advocates and oncologists, which stands in contrast to their dissatisfaction with existing chemotherapy educational materials.

Our intervention has several unique strengths. First, it leverages the IC moment to promote accurate expectations from the outset of treatment. This may help patients better plan and prepare for the future. Second, it uses dual mediums so that patients can access information in a preferred format. Next, it presents difficult prognostic information from multiple credible experts, thereby supporting oncologists in one of their most challenging communication tasks.[8,34]. The intervention is unambiguous about the non-curative potential of palliative chemotherapy; however, life expectancy statistics are presented in a way that gives patients control over whether/when to access this information. This optional approach was strongly preferred by advocates and oncologists, and aligns with prevailing expert recommendations to tailor prognostic information to patient preferences.[19,35–37] Finally, our intervention challenges the current paradigm of patient education by incorporating patient voices. Clinician perspectives are unavoidably shaped by their training, professional roles and culture [21]. As a result, oncologists often struggle to communicate effectively [15,38,39], they underestimate the impact of treatment on quality of life [40], and they overlook patient-centered concerns [41]. Advocates were unanimous in their views that patient voices strengthened the intervention.

Although few interventions have been specifically developed to support chemotherapy IC [42,43], our work must be placed in the context of other efforts to improve advanced cancer patients’ understanding of their illness and treatment options. A few studies suggest that decision aids may improve patients’ understanding of palliative chemotherapy options.[44,45] Unfortunately decision support tools have not been adopted into this clinical context. As cancer medicine rapidly evolves, chemotherapy options must be weighed in light of multiple parameters including molecular alterations, comorbidity, prior treatments, and patient preferences. These complexities make the creation and maintenance of chemotherapy decision aids very difficult. Our modular suite of IC tools which describe individual regimens may be a more practical scalable approach. Other studies have shown that audio-recording oncology consultations improves patient understanding and satisfaction. [46–48] Unfortunately oncologists have been reticent to adopt this approach due to medicolegal concerns.[48,49] Moreover, the utility of audio-recordings is limited by any information/communication gaps inherent within the original consultation, such as lack of prognostic disclosure.[15] Our intervention has the advantage of providing balanced, comprehensive, and evidence-based information about treatment risks/benefits and prognosis. Patient coaching and/or question prompt-lists have been shown to help engage patients in care decisions, improve understanding [50–52] and potentially promote prognostic discussions.[53,54] If our intervention proves successful, combining IC video tools with question prompt lists or audio-recordings could be examined.

Our experience illustrates many advantages of partnering with patient stakeholders in the development of patient education interventions. Patients’ worldview is shaped by personal experiences which can help investigators overcome inherent biases and better meet the needs of end-users[21,55]. Patient engagement unquestionably made our intervention more relevant to the concerns and priorities of patients. Our use of flexible and varied engagement methods allowed us to consider the perspectives of diverse participants in the IC process, and it facilitated efficient stakeholder-driven revisions throughout the project.

Patient engagement is common in the development of educational or decision support interventions [25,56–60] and upheld in best practices. [25,26] In practice however, patients are frequently relegated to narrow project roles that lack true influence over the process.[23,24] Patients commonly participate in advisory panels[25,26,56], focus groups (e.g. to set content priorities) [57,59] or participate in alpha and beta testing [26,60]. These processes are useful, but not necessarily sufficient to promote meaningful stakeholder-research exchanges and true impact. We sought genuine partnerships by integrating stakeholders into our core research team, which shared editorial control over the project. Our lead patient advocate coordinated all patient engagement efforts and served as a liaison to the core research team to ensure that their feedback was heard and integrated. Our patient stakeholder panels also held critical roles, providing longitudinal guidance throughout the project, drafting portions of the intervention, and helping our team interpret and act upon survey results. Perhaps most importantly, we allowed patients to directly share their experiences and perspectives within the IC intervention.

Despite the clear benefits, patient engagement is challenging, time-consuming, and it requires significant investment.[24,27] Similar to others,[27] our stakeholders enthusiasm often led to ideas beyond our project scope. Stakeholders also had differences of opinion that required balancing. Perhaps unique to our particular project, many of our stakeholders were ill with metastatic cancer. This made in-person meetings difficult, and required extra flexibility to meet patients individually or exchange ideas via phone or email.

Despite the favorable ratings of our intervention, there are several limitations to our study. Acceptability was assessed among advocates whose perspectives may differ from patients. Similarly, our oncologist cohort was small and consisted primarily of academic clinicians. Our ongoing multicenter randomized study will determine the acceptability and impact of our intervention in a larger, more representative sample.

4.2. Conclusion

In summary, the current chemotherapy IC process is flawed and existing tools are inadequate to meet patients’ needs [7,8,10,15]. By partnering with stakeholders we created a patient-centered chemotherapy IC tool acceptable to patient advocates and oncologists. A randomized trial is currently examining its impact on the quality of informed decision-making and patients’ satisfaction with the chemotherapy IC process.

4.3. Practice Implications

Given the oncology professions’ commitment to the chemotherapy IC process and deficits in available resources, our intervention fills a critical need for patients, caregivers and clinicians. This strategy could be adapted to other cancers and integrate into routine care. If proven effective, patient-centered IC tools may be a scalable strategy to enhance patient-provider communication and improve the quality of cancer care.

We created a patient-centered intervention supporting chemotherapy informed consent

The intervention was rated highly by patient advocates and oncologists

Inclusion of patient voices (e.g. video clips and quotes) was considered a key strength

Figure 4.

Patient advocate perspectives about sections communicating the impact of chemotherapy on prognosis

Acknowledgments

Funding source: This study was supported by a grant from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (CE-1304-6517) to Dr. Schrag, a Charles A. King Foundation Trust Fellowship Award to Dr. A. Enzinger, and a Junior Faculty Award to Dr. A Enzinger through the NCI grant 1UG1CA189823 to the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Previous presentation: none

Disclaimers: none

Conflicts of Interest: None

Consent. I confirm all patient/personal identifiers have been removed or disguised so the patient/person(s) described are not identifiable and cannot be identified through details of the story. Patients filmed or photographed within the intervention described herein have all signed media releases authorizing use for the purpose of this project and related publications.

Contributors

Andrea C. Enzinger: conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript, final approval

Jennifer K. Wind: conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, acquisition of data, review of manuscript, final approval

Elizabeth Frank: conception and design, review of manuscript, final approval

Nadine J. McCleary: conception and design, review of manuscript, final approval

Laura Porter: conception and design, review of manuscript, final approval

Heather Cushing: conception and design, review of manuscript, final approval

Caroline Abbott: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, review of manuscript, final approval

Christine Cronin: analysis and interpretation of data, review of manuscript, final approval

Peter C. Enzinger: conception and design, review of manuscript, final approval

Neal J. Meropol: conception and design, review of manuscript, final approval

Deborah Schrag: conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, review of article, final approval

References

- 1.Annas GJ. Informed consent, cancer, and truth in prognosis. N Engl J Med. 1994 Jan 20;330(3):223–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199401203300324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peppercorn JM, Smith TJ, Helft PR, Debono DJ, Berry SR, Wollins DS, Hayes DM, Von Roenn JH, Schnipper LE. American society of clinical oncology statement: toward individualized care for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011 Feb 20;29(6):755–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackwell AC, Boothman RC. Documenting Informed Consent for Chemotherapy. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2007;3(4):194–95. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0742501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.QOPI Certification Site Assessment Standards. 2013 http://qopi.asco.org/Documents/QCPstandards_Round8_01_15_2013.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2013.

- 5.Cassileth BR, Zupkis RV, Sutton-Smith K, March V. Informed consent – why are its goals imperfectly realized? N Engl J Med. 1980 Apr 17;302(16):896–900. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198004173021605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gattellari M, Butow PN, Tattersall MH, Dunn SM, MacLeod CA. Misunderstanding in cancer patients: why shoot the messenger? Ann Oncol. 1999 Jan;10(1):39–46. doi: 10.1023/a:1008336415362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, Gallagher ER, Jackson VA, Lynch TJ, Lennes IT, Dahlin CM, Pirl WF. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2011 Jun 10;29(17):2319–26. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, Finkelman MD, Mack JW, Keating NL, Schrag D. Patients’ expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012 Oct 25;367(17):1616–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meropol NJ, Weinfurt KP, Burnett CB, Balshem A, Benson AB, 3rd, Castel L, Corbett S, Diefenbach M, Gaskin D, Li Y, Manne S, Marshall J, Rowland JH, Slater E, Sulmasy DP, Van Echo D, Washington S, Schulman KA. Perceptions of patients and physicians regarding phase I cancer clinical trials: implications for physician-patient communication. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Jul 1;21(13):2589–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Jawahri A, Traeger L, Park ER, Greer JA, Pirl WF, Lennes IT, Jackson VA, Gallagher ER, Temel JS. Associations among prognostic understanding, quality of life, and mood in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer. 2014 Jan 15;120(2):278–85. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weinfurt KP, Seils DM, Lin L, Sulmasy DP, Astrow AB, Hurwitz HI, Cohen RB, Meropol NJ. Research participants’ high expectations of benefit in early-phase oncology trials: are we asking the right question? J Clin Oncol. 2012 Dec 10;30(35):4396–400. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.6587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Enzinger AC, Zhang B, Schrag D, Prigerson HG. Outcomes of Prognostic Disclosure: Associations With Prognostic Understanding, Distress, and Relationship With Physician Among Patients With Advanced Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015 Nov 10;33(32):3809–16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.9239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weeks JC, Cook EF, O’Day SJ, Peterson LM, Wenger N, Reding D, Harrell FE, Kussin P, Dawson NV, Connors AF, Jr, Lynn J, Phillips RS. Relationship between cancer patients’ predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. J Amer Med Assoc. 1998 Jun 3;279(21):1709–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mack JW, Walling A, Dy S, Antonio AL, Adams J, Keating NL, Tisnado D. Patient beliefs that chemotherapy may be curative and care received at the end of life among patients with metastatic lung and colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2015 Feb 11; doi: 10.1002/cncr.29250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenkins V, Solis-Trapala I, Langridge C, Catt S, Talbot DC, Fallowfield LJ. What oncologists believe they said and what patients believe they heard: an analysis of phase I trial discussions. J Clin Oncol. 2011 Jan 1;29(1):61–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.0814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Audrey S, Abel J, Blazeby JM, Falk S, Campbell R. What oncologists tell patients about survival benefits of palliative chemotherapy and implications for informed consent: qualitative study. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 2008;337:a752. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gattellari M, Voigt KJ, Butow PN, Tattersall MH. When the treatment goal is not cure: are cancer patients equipped to make informed decisions? J Clin Oncol. 2002 Jan 15;20(2):503–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.2.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jenkins V, Fallowfield L, Saul J. Information needs of patients with cancer: results from a large study in UK cancer centres. Br J Cancer. 2001 Jan 5;84(1):48–51. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hagerty RG, Butow PN, Ellis PA, Lobb EA, Pendlebury S, Leighl N, Goldstein D, Lo SK, Tattersall MH. Cancer patient preferences for communication of prognosis in the metastatic setting. J Clin Oncol. 2004 May 1;22(9):1721–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.del Carmen MG, Joffe S. Informed consent for medical treatment and research: a review. The oncologist. 2005 Sep;10(8):636–41. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-8-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frank L, Basch E, Selby JV, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research I The PCORI perspective on patient-centered outcomes research. J Amer Med Assoc. 2014 Oct 15;312(15):1513–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.11100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenberg CC, Wind JK, Chang GJ, Chen RC, Schrag D. Stakeholder engagement for comparitive effectivenss research in cancer care: experience of the DEcIDE Cancer Consortium. Journal of Comparitive Effectiveness Research. 2013;2(2):117–25. doi: 10.2217/cer.12.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Concannon TW, Fuster M, Saunders T, Patel K, Wong JB, Leslie LK, Lau J. A systematic review of stakeholder engagement in comparative effectiveness and patient-centered outcomes research. J Gen Intern Med. 2014 Dec;29(12):1692–701. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2878-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deverka PA, Lavallee DC, Desai PJ, Esmail LC, Ramsey SD, Veenstra DL, Tunis SR. Stakeholder participation in comparative effectiveness research: defining a framework for effective engagement. J Comp Eff Res. 2012 Mar;1(2):181–94. doi: 10.2217/cer.12.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elwyn G, Kreuwel I, Durand MA, Sivell S, Joseph-Williams N, Evans R, Edwards A. How to develop web-based decision support interventions for patients: a process map. Patient Educ Couns. 2011 Feb;82(2):260–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Volk RJ, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Stacey D, Elwyn G. Ten years of the International Patient Decision Aid Standards Collaboration: evolution of the core dimensions for assessing the quality of patient decision aids. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13(Suppl 2):S1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-S2-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duffett L. Patient engagement: What partnering with patient in research is all about. Thromb Res. 2016 Oct 28; doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2016.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meropol NJ, Wong YN, Albrecht T, Manne S, Miller SM, Flamm AL, Benson AB, 3rd, Buzaglo J, Collins M, Egleston B, Fleisher L, Katz M, Kinzy TG, Liu TM, Margevicius S, Miller DM, Poole D, Roach N, Ross E, Schluchter MD. Randomized Trial of a Web-Based Intervention to Address Barriers to Clinical Trials. J Clin Oncol. 2016 Feb 10;34(5):469–78. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow MK, Mitchell SL, El-Jawahri A, Davis AD, Barry MJ, Hartshorn KL, Jackson VA, Gillick MR, Walker-Corkery ES, Chang Y, Lopez L, Kemeny M, Bulone L, Mann E, Misra S, Peachey M, Abbo ED, Eichler AF, Epstein AS, Noy A, Levin TT, Temel JS. Randomized controlled trial of a video decision support tool for cardiopulmonary resuscitation decision making in advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013 Jan 20;31(3):380–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.9570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abrams TA, Meyer G, Moloney J, Meyerhardt JA, Schrag D, Fuchs CS. Patterns of chemotherapy use in a U.S.-wide population-based cohort of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;2012:30. suppl; abstr 3537. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Faden R, Beauchamp T. A History and Theory of Informed Consent. New York: Oxford University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shoemaker SJ, Wolf MS, Brach C. In: The Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT) and User’s Guide. Quality AfHRa, editor. Rockville, MD: AHRQ; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Britten N. Qualitative interviews in medical research. BMJ. 1995 Jul 22;311(6999):251–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6999.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanco K, Rhondali W, Perez-Cruz P, Tanzi S, Chisholm GB, Baile W, Frisbee-Hume S, Williams J, Masino C, Cantu H, Sisson A, Arthur J, Bruera E. Patient Perception of Physician Compassion After a More Optimistic vs a Less Optimistic Message: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2015 May;1(2):176–83. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2014.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bernacki RE, Block SD, American College of Physicians High Value Care Task F Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Dec;174(12):1994–2003. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Enzinger AC, Zheng B, Shrag D, Prigerson HG. Outcomes of prognostic disclosure: Effects on advanced cancer patients’ prognostic understanding, mental health, and relationship with their oncologist. J Clin Oncol. 2015 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.9239. Forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fallowfield L, Ford S, Lewis S. No news is not good news: information preferences of patients with cancer. Psycho-oncology. 1995 Oct;4(3):197–202. doi: 10.1002/pon.2960040305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gabrijel S, Grize L, Helfenstein E, Brutsche M, Grossman P, Tamm M, Kiss A. Receiving the diagnosis of lung cancer: patient recall of information and satisfaction with physician communication. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Jan 10;26(2):297–302. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.0609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gaston CM, Mitchell G. Information giving and decision-making in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review. Social science & medicine. 2005 Nov;61(10):2252–64. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Di Maio M, Gallo C, Leighl NB, Piccirillo MC, Daniele G, Nuzzo F, Gridelli C, Gebbia V, Ciardiello F, De Placido S, Ceribelli A, Favaretto AG, de Matteis A, Feld R, Butts C, Bryce J, Signoriello S, Morabito A, Rocco G, Perrone F. Symptomatic toxicities experienced during anticancer treatment: agreement between patient and physician reporting in three randomized trials. J Clin Oncol. 2015 Mar 10;33(8):910–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.9334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pollak KI, Arnold RM, Jeffreys AS, Alexander SC, Olsen MK, Abernethy AP, Sugg Skinner C, Rodriguez KL, Tulsky JA. Oncologist communication about emotion during visits with patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Dec 20;25(36):5748–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gori S, Greco MT, Catania C, Colombo C, Apolone G, Zagonel V, Oncology AGftICiM A new informed consent form model for cancer patients: preliminary results of a prospective study by the Italian Association of Medical Oncology (AIOM) Patient Educ Couns. 2012 May;87(2):243–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olver IN, Whitford HS, Denson LA, Peterson MJ, Olver SI. Improving informed consent to chemotherapy: a randomized controlled trial of written information versus an interactive multimedia CD-ROM. Patient Educ Couns. 2009 Feb;74(2):197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brundage MD, Feldman-Stewart D, Cosby R, Gregg R, Dixon P, Youssef Y, Davies D, Mackillop WJ. Phase I study of a decision aid for patients with locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001 Mar 1;19(5):1326–35. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.5.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leighl NB, Shepherd HL, Butow PN, Clarke SJ, McJannett M, Beale PJ, Wilcken NR, Moore MJ, Chen EX, Goldstein D, Horvath L, Knox JJ, Krzyzanowska M, Oza AM, Feld R, Hedley D, Xu W, Tattersall MH. Supporting treatment decision making in advanced cancer: a randomized trial of a decision aid for patients with advanced colorectal cancer considering chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2011 May 20;29(15):2077–84. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.0754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bruera E, Pituskin E, Calder K, Neumann CM, Hanson J. The addition of an audiocassette recording of a consultation to written recommendations for patients with advanced cancer: A randomized, controlled trial. Cancer. 1999 Dec 1;86(11):2420–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolderslund M, Kofoed PE, Holst R, Axboe M, Ammentorp J. Digital audio recordings improve the outcomes of patient consultations: A randomised cluster trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2017 Feb;100(2):242–49. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tattersall MH, Butow PN. Consultation audio tapes: an underused cancer patient information aid and clinical research tool. Lancet Oncol. 2002 Jul;3(7):431–7. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00790-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McConnell D, Butow PN, Tattersall MH. Audiotapes and letters to patients: the practice and views of oncologists, surgeons and general practitioners. Br J Cancer. 1999 Apr;79(11–12):1782–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clayton JM, Butow PN, Tattersall MH, Devine RJ, Simpson JM, Aggarwal G, Clark KJ, Currow DC, Elliott LM, Lacey J, Lee PG, Noel MA. Randomized controlled trial of a prompt list to help advanced cancer patients and their caregivers to ask questions about prognosis and end-of-life care. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Feb 20;25(6):715–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Epstein RM, Duberstein PR, Fenton JJ, Fiscella K, Hoerger M, Tancredi DJ, Xing G, Gramling R, Mohile S, Franks P, Kaesberg P, Plumb S, Cipri CS, Street RL, Jr, Shields CG, Back AL, Butow P, Walczak A, Tattersall M, Venuti A, Sullivan P, Robinson M, Hoh B, Lewis L, Kravitz RL. Effect of a Patient-Centered Communication Intervention on Oncologist-Patient Communication, Quality of Life, and Health Care Utilization in Advanced Cancer: The VOICE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2017 Jan 01;3(1):92–100. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gramling R, Fiscella K, Xing G, Hoerger M, Duberstein P, Plumb S, Mohile S, Fenton JJ, Tancredi DJ, Kravitz RL, Epstein RM. Determinants of Patient-Oncologist Prognostic Discordance in Advanced Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016 Nov 01;2(11):1421–26. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rodenbach RA, Brandes K, Fiscella K, Kravitz RL, Butow PN, Walczak A, Duberstein PR, Sullivan P, Hoh B, Xing G, Plumb S, Epstein RM. Promoting End-of-Life Discussions in Advanced Cancer: Effects of Patient Coaching and Question Prompt Lists. J Clin Oncol. 2017 Jan 30;:JCO2016685651. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.5651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walczak A, Butow PN, Tattersall MH, Davidson PM, Young J, Epstein RM, Costa DS, Clayton JM. Encouraging early discussion of life expectancy and end-of-life care: A randomised controlled trial of a nurse-led communication support program for patients and caregivers. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017 Feb;67:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fleurence RL, Forsythe LP, Lauer M, Rotter J, Ioannidis JP, Beal A, Frank L, Selby JV. Engaging patients and stakeholders in research proposal review: the patient-centered outcomes research institute. Ann Intern Med. 2014 Jul 15;161(2):122–30. doi: 10.7326/M13-2412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fleisher L, Ruggieri DG, Miller SM, Manne S, Albrecht T, Buzaglo J, Collins MA, Katz M, Kinzy TG, Liu T, Manning C, Charap ES, Millard J, Miller DM, Poole D, Raivitch S, Roach N, Ross EA, Meropol NJ. Application of best practice approaches for designing decision support tools: the preparatory education about clinical trials (PRE-ACT) study. Patient Educ Couns. 2014 Jul;96(1):63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gogovor A, Visca R, Auger C, Bouvrette-Leblanc L, Symeonidis I, Poissant L, Ware MA, Shir Y, Viens N, Ahmed S. Informing the development of an Internet-based chronic pain self-management program. Int J Med Inform. 2017 Jan;97:109–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hogden A, Greenfield D, Caga J, Cai X. Development of patient decision support tools for motor neuron disease using stakeholder consultation: a study protocol. BMJ Open. 2016 Apr 06;6(4):e010532. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaiser K, Cheng WY, Jensen S, Clayman ML, Thappa A, Schwiep F, Chawla A, Goldberger JJ, Col N, Schein J. Development of a shared decision-making tool to assist patients and clinicians with decisions on oral anticoagulant treatment for atrial fibrillation. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015 Dec;31(12):2261–72. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2015.1096767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sun V, Kim JY, Raz DJ, Chang W, Erhunmwunsee L, Uranga C, Ireland AM, Reckamp K, Tiep B, Hayter J, Lew M, Ferrell B, McCorkle R. Preparing Cancer Patients and Family Caregivers for Lung Surgery: Development of a Multimedia Self-Management Intervention. J Cancer Educ. 2016 Aug 20; doi: 10.1007/s13187-016-1103-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]