Abstract

Background:

Liquid-based cytology (LBC) has been developed as an alternative for conventional cytology (CC) in cervical smears. It is now increasingly being used all over the world for cervical cancer screening. However, its role and diagnostic accuracy in bronchial wash (BW)/bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) specimens remains undetermined.

Aims:

To assess and compare the diagnostic performance and accuracy of LBC with CC for detecting malignancy in bronchial specimens.

Settings and Design:

This was a retrospective analytical hospital-based study.

Materials and Methods:

Bronchial specimens (BW/BAL) received over a period of 4.5 years were reviewed. The samples were processed by CC from June 2010 to September 2012 (2.25 years) and by LBC from October 2012 to December 2014 (2.25 years). Data were retrieved from the records of cytology laboratory and compared among both the groups. Detection rate for histologically or cytologically verified samples was calculated.

Results:

A total of 559 cases verified by histological and cytological follow-up were evaluated. These included 247 CC cases and 312 LBC cases. The positive diagnostic rate for malignancy in CC was 28.6% whereas that for LBC was 32.9%. The negative diagnostic rates were 66.5% and 66.3% for CC and LBC, respectively. However, unsatisfactory rates had shown a good reduction from 4.4% in CC to 0.6% after LBC introduction. The smears showed more homogeneous distribution of cells with elimination of obscuring factors such as blood, inflammation, and mucus.

Conclusions:

The diagnostic accuracy of LBC was slightly better than CC. The unsatisfactory rates showed reduction in LBC preparation. Thus, LBC is a viable alternative to CC and has the advantages of standardization of preparation with decrease in unsatisfactory rates.

Key words: Bronchoalveolar lavage, bronchial wash, conventional cytology, liquid-based cytology, lung cancer

Introduction

Lung carcinoma is the leading cause of cancer mortality in India.[1] In addition to primary tumor, lung is also a common site for metastatic tumors.[2] Most lung cancer patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage of the disease, making curable surgery not an option. Hence, early diagnosis and effective treatment are keys to prolong the survival of lung cancer patients.[3]

Cytology has been widely used for the diagnosis of lung malignancy. The cytological specimens used include sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), bronchial washings (BWs), bronchial brushings, and percutaneous/endobronchial fine-needle aspiration cytology.[4] Bronchial cytology specimens are of considerable diagnostic value in the evaluation of lung cancer, especially in cases where it is difficult to obtain bronchoscopic biopsy material for histologic evaluation as well as in peripheral lesions. The sensitivity of bronchial wash/lavage cytology has been variably reported to be 39.4–80.5%.[5,6]

In most centres, conventional direct smear technique is used to prepare smears for microscopic examination. Conventional smears suffer from problems such as variable specimen thickness, nonuniformity of slides, preparation and fixation artefacts, overlapping cellular material, obscuring elements such as mucus, inflammation and blood, and poor cellular preservation.[7]

Recent advances in cytopathological techniques include the development of liquid-based cytology (LBC), which has largely been applied in gynecological samples with favorable results.[8,9,10]

Considering the analogy that use of LBC technology has taken care of similar problems faced in gynecological samples, few studies have been performed to investigate if LBC preparation would improve the sensitivity of bronchial cytology samples. There is limited literature regarding application of LBC in BAL with no clear cut recommendations. Hence, the present study was designed to evaluate the utility of LBC in BW/BAL specimens from patients with clinical or radiological suspicion of malignancy and to compare the diagnostic accuracy of LBC and conventional cytology (CC).

Materials and Methods

A retrospective review of bronchial cytology specimens received in cytology laboratory of our hospital over a period of 4.5 years from June 2010 to December 2014 was done by retrieving data from records.

Cases with clinical and/or radiological suspicion of malignancy were included in the study. The clinical and radiologic details were recorded from cytology requisition forms. Follow-up data in the form of bronchial biopsy or endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS)/computed tomography (CT) guided fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) from lung and mediastinal nodes were also retrieved. This study compared the performance of CC with LBC in specimens received over two different periods. This is not a split sample study.

During the period June 2010 to September 2012, bronchial cytology specimens were processed by CC. This included cytospin smears and direct smears after centrifugation. From October 2012, the laboratory switched to LBC technology (Sure Path, Becton Dickinson and company, Burlington, USA) for processing bronchial cytology specimens.

Processing method by conventional technique

The BAL/BW fluid was taken in a test tube and centrifuged at 2200 revolutions per minute (rpm) for 10–15 min. The supernatant was discarded and two direct smears were prepared from the deposit. One smear was stained with Papanicolaou stain whereas the other was kept for special stains, if needed.

Two cytospin smears were prepared by placing 1 ml fluid in the cytofunnel and spinning at 1500 rpm for 15 min. The smears were stained by Papanicolaou stain.

Processing method by liquid-based cytology Sure Path system

Bronchial lavage/wash fluid was mixed by manually shaking the container to homogenize the sample. Equal volume of Cytorich Red (Sure Path, Becton, Dickinson and company, Burlington, USA) solution was added thereafter to the specimen, vortexed, and kept overnight for fixation. After fixation, specimen was processed and stained according to the Sure Path manual protocol in fully automated LBC machine leading to the preparation of two Pap-stained slides, which were removed and cover slipped.

Cytology reporting

Reporting of the slides had been done by the same cytopathologists during both the periods. On the basis of cytomorphology, cases in both the groups were divided into four diagnostic categories as follows:

Positive: Included cases with definite malignant cells in adequate cellularity.

Suspicious of malignancy: Included cases with few atypical cells highly suggestive of malignancy.

Negative: Included cases with normal cellular components (alveolar macrophages, ciliated columnar cells) and/or inflammatory cells without any atypical cells.

Unsatisfactory: Included cases with few/no epithelial cells and alveolar macrophages, excessive background obscuration with inflammation, blood, mucus, or excessive degenerative changes with no preserved cellular morphology.

Typing of tumor

Tumors were typed as small cell carcinoma and nonsmall cell carcinoma (NSCC). NSCC were further subtyped as adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma on the basis of morphological features, wherever possible. Cases were typed as NSCC–NOS (not otherwise specified) where further characterization was not possible on the basis of morphology.

Follow-up

The cytopathology results were correlated with the results of subsequent bronchial biopsy or FNAC. Comparison of cytology results during the two periods using CC and LBC was also done with respect to sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, positive and negative diagnostic rates, and unsatisfactory rates.

Results

A total of 821 cases were evaluated which included 382 samples processed by CC and 439 samples processed by LBC technology. Follow-up data was available in 247 out of 382 samples in the CC group and 312 in 439 cases in the LBC group; only these were included in the study for analysis. The rest of the cases were excluded as no follow-up information could be obtained from records.

General appearance and satisfactory rates

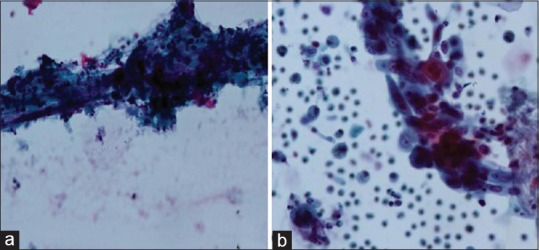

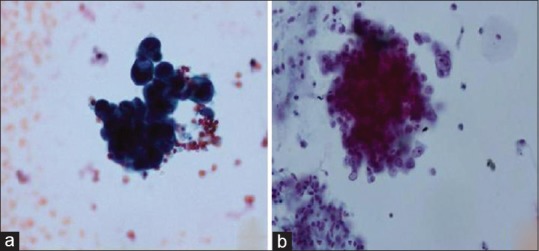

The smears prepared by LBC technology concentrated the cells into a defined area for cytological examination and showed uniform distribution of cells. The background was clean with no background mucus, blood, and inflammatory cells. Malignant and atypical cells were easily identified with better preservation of nuclear and cytoplasmic features [Figure 1a and b]. The three-dimensional architecture of tumor cells was also retained [Figure 2a and b].

Figure 1.

Comparison of CC and LBC in BAL specimen in cases of squamous cell carcinoma. (a) CC preparation shows atypical keratinised cellls entrapped in inflammatory exudate. (Pap stain x600), (b) LBC preparation shows atypical squamous cells with preserved nuclear and cytoplasmic details in a cleaner background (Pap stain x600)

Figure 2.

Comaprison of CC and LBC in BAL specimens in cases of adenocarcinoma, (a) CC preparation showing clusters of adenocarcinoma (Pap stain x600). (b) LBC preparation showing preserved three dimensional clusters of adenocarcinoma (Pap stain x600)

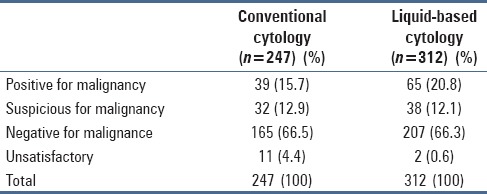

Unsatisfactory rates showed significant reduction from 4.4% in the CC group to 0.6% in the LBC group [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison of diagnostic rates in conventional cytology and liquid-based cytology

Cytology results

Table 1 gives the diagnostic rates of BW as processed by the two techniques. The positive detection rate of malignancy was 28.6% in the CC group whereas it was 32.9% in the LBC group. The negative rates were almost similar in both the groups (66.5% and 66.3% in CC and LBC group).

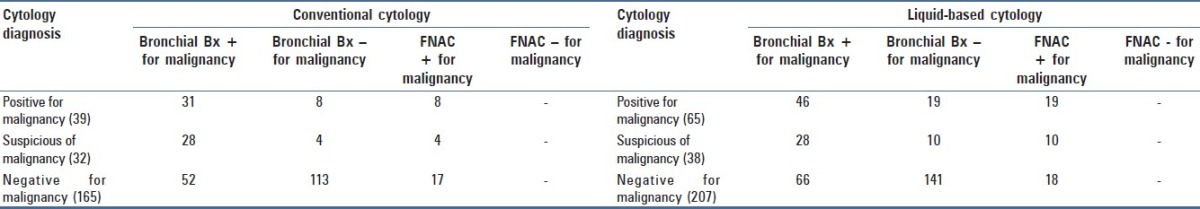

Table 2 presents a comparison of cytology diagnosis with follow-up data. Out of the total 71 positive and suspicious cases in CC group, 59 (83%) had bronchial biopsy positive for malignancy whereas 12 (16.9%) had FNA (CT/EBUS–TBNA) positive for carcinoma. Out of the total 103 positive and suspicious cases of malignancy in the LBC group, 74 (71.8%) had bronchial biopsy positive for malignancy whereas 29 (28.1%) had subsequent FNAC (CT/EBUS–TBNA) positive for carcinoma. Hence, there were no false positive cases in either group.

Table 2.

Comparison of cytodiagnosis with follow-up

True negatives were 58.2% (96 of 165 cases) in the CC group and 59.4% (123 of 207 cases) in the LBC group. False negatives were 41.8% (69 of 165 cases) and 40.6% (84 of 207 cases) in CC and LBC groups, respectively. The true negative and false negative rates were comparable in both the groups.

Typing of tumor

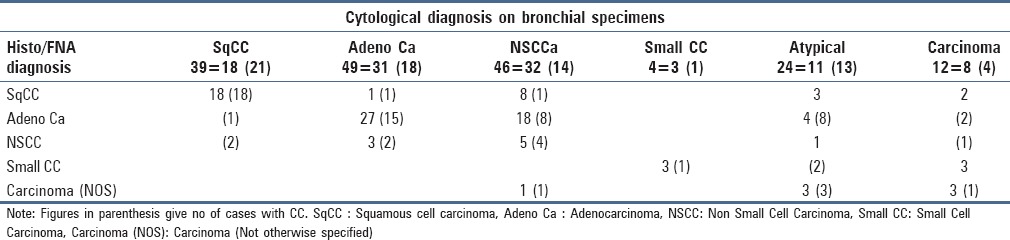

Table 3 illustrates a comparison of cytological subtyping of tumors in BW/BAL specimens with follow-up data. All cases diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma (SQCC) on LBC were subtyped correctly when compared with subsequent biopsy/FNA diagnosis. One case diagnosed as SQCC on CC was typed as adenocarcinoma on follow-up. In the cases diagnosed as adenocarcinoma in both the groups, one case each turned out to be SQCC on follow-up. All cases of SCC were correctly typed on LBC and CC when compared with follow-up. In the LBC group, 32 cases were categorized as NSCC without further subtyping. Twenty six of these 32 cases could be further subclassified as SQCC and adenocarcinoma on follow-up. Similarly, in the CC group, out of 14 cases diagnosed as NSCC only, 9 cases could be further subtyped on follow-up. The subtyping on follow-up was done with the application of immunohistochemistry (IHC) on biopsies/FNACs.

Table 3.

Comparison of cytological tumor subtyping with follow-up

Accuracy

The sensitivity was 50.7% and 55.8% for CC and LBC, respectively, whereas the specificity for both was 100%. Thus, LBC showed slightly better sensitivity in this study. Similarly, negative predictive value marginally improved with LBC technology (59.4% for LBC Vs 58.2% for CC). The positive predictive value was 100% for both the techniques.

Discussion

Respiratory cytology is increasingly being used in the initial evaluation of pulmonary disorders, especially in suspected lung cancer. BW/lavage cytology is a widely accepted, safe, simple, and minimally invasive technique to evaluate lung pathologies. Moreover, bronchial wash technique samples out peripheral areas of lung that are beyond the reach of bronchial brush.[4] Literature review shows a wide range of sensitivity and specificity of BW/lavage for the diagnosis of lung carcinoma. Using CC methods, the sensitivity varies from 39.4% to 80.5% whereas specificity ranges between 80.0% and 96.6%.[4,5,6] Conventional preparation of BW/lavage involves direct smears and cytospin preparations. Preparing optimal smears can be challenging due to the presence of mucus, blood, and inflammation.

In the present study, the sensitivity of BW/lavage in the detection of lung cancer by the conventional method was 50.07% whereas the specificity was 100%. This compares well with that reported in literature.[4,5,6]

LBC (Sure path) is an automated cytopreparatory technique which is now widely used in gynecological specimens.[8,9,10] Few researchers have applied LBC technology to BW/lavage specimens and only limited data on its utility is available in the literature.

CC techniques (cytospin and centrifugation) were used in our lab for processing bronchial lavage/wash specimens before the introduction of the LBC (Sure path) technique. The cytology results of both CC and LBC era in suspected lung cancer cases over a similar time period (2.25 years) were compared to assess the diagnostic value of LBC in these specimens.

The sensitivity of BW/BAL in the detection of lung cancer using LBC (Sure Path) was 55.8% as compared to 50.07% by the conventional technique. Therefore, there was a marginal improvement with the introduction of the LBC technique.

The specificity of bronchial washing in the detection of malignancy was 100% with the use of both techniques. There was no false positive case in either group. Therefore, BW had a high positive predictive value. Similar high specificity of BW has been reported in literature i.e., 80%[4] to 96.6%.[6]

Unsatisfactory rates showed a significant reduction from 4.4% in CC to 0.6% in LBC. This can be attributed to numerous factors such as removal of mucus, blood, inflammatory cells, and other obscuring factors with the use of LBC, which renders better visualization of cells, a well spread out monolayer preparation, and standardization of procedure.

This study had the limitation that the same specimen was not split for comparing the two techniques of bronchial specimen processing. This was a retrospective study where the results of the two periods of CC and LBC use were compared.

To the best of our knowledge, there are six published series comparing the conventional and LBC technique for processing of bronchial specimens in the detection of lung carcinoma. Two of the investigators,[7,11] like in the present study, performed a retrospective comparative analysis of BW processed by CC and LBC.

Yang et al.[7] studied samples equally divided between the two groups and found a positive detection rate of 35.84% and 11.83%, respectively, in the LBC and CC groups, which was statistically significant. Kathiresan et al.[11] compared the two periods of CC use (n = 114) and LBC use (n = 126) and found 68% positive cytology in LBC compared to 38% in CC.

In the current study, the positive detection rate of carcinoma was marginally better with the use of LBC (33%) than CC (28.05%) whereas the negative detection rates were almost similar in both the groups (66.5% and 66.3%).

Other investigators used split sample technique to illustrate the difference between the two processing methods. Zardawei et al.[12] processed bronchial specimens by first preparing direct and cytospin smears and used the remainder to prepare the LBC smears. They evaluated 53 BW specimens and found agreement between 51 samples. They reported equal sensitivity for both the methods in detecting malignancy. Rana et al.[13] studied 207 split sample bronchial specimens and found no significant difference between the two diagnostic categories. Koivurinne et al.[14] used 431 split samples of BW after treatment with dithiotheritol and prepared 1 Thin Prep and 2–4 conventional smears from the sample. They concluded that the diagnostic accuracy of 1 Thin Prep smear was comparable to 2–4 conventional smears.

Astall et al.[15] evaluated 137 BAL specimens. After preparation for diagnostic purposes with the direct smear method, the remaining sample was processed using LBC (Cyto SED system). They found that 71% of the malignant diagnoses were confirmed by CC whereas 91% were confirmed by LBC. Thus, they reported that LBC technique identified more malignancies than CC.

Our study showed comparable sensitivity and specificity of LBC and CC in the detection of malignancy with only marginal improvement by LBC. Similar comparable results have been reported by some authors such as Rana et al., Zardawei et al., and Kouvuireine et al.[12,13,14] Other authors have reported significant difference between the two techniques.[7,11,15]

Limitation of present study was comparison of two techniques over different periods of time rather than split sample technique. Split sample technique is definitely better at evaluation of CC versus LBC use than comparing results over the two historical periods. However, the present results are significant as the number of samples in both periods of time were large, and the results are comparable to those reported in literature from western world.

The precise subclassification of lung cancer is critical for effective patient management. This is specifically applicable for advanced lung cancer patients with unresectable disease.[3]

In the current study, we compared the positive cytological diagnosis with biopsy/FNAC follow up. Typing of tumors on small biopsies or FNA samples was done on the basis of morphology and IHC, whereas typing on BW was done solely on morphology. We were able to correctly subtype cases as ADC, SQCC, and SCC using LBC (46.5%) and CC (47.8%) in a comparable number of cases.

The main advantage of LBC in bronchial specimens was monolayered distribution of cells with better preservation of cellular morphology. The cytomorphological features were better defined without loss of three-dimensional configuration. The background obscuring factors (such as blood, inflammatory cells, and mucus) were removed making interpretation easier. Similar observations have been made by other authors regarding the preparation of smears.[12,13,15,16,17]

A general observation was made by the three observers that the overall screening time was reduced with the use of LBC. However, the difference in screening time was not methodically calculated between the two techniques in this study. A standardization of preparations with the introduction of LBC was also observed.

Thus, we conclude that the introduction of LBC for BW/lavage specimens was associated with slightly increased diagnostic rate of malignancy as compared to CC and showed a reduction in unsatisfactory rates. Hence, LBC is a viable alternative to CC in processing of BW specimens, especially in laboratories which have an LBC system in place for gynacological specimens.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Malik PS, Raina V. Lung cancer: Prevalent trends and emerging concepts. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141:5–7. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.154479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solomides CC, Johnston WW, Elson CE. Respiratory tract. In: Bibbo M, Wilbur DC, editors. Comprehensive Cytopathology. 4th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier Saunders; 2015. pp. 285–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu C, Wen Z, Li Y, Peng L. Application of Thin Prep Bronchial Brushing Cytology in the early diagnosis of Lung Cancer: A retrospective Study. Plos One. 2014;9:1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao S, Rao S, Lal A, Barathi G, Dhanasekar T, Duvuru P. Bronchial wash cytology: A study on morphology and morphometry. J Cytol. 2014;31:63–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.138664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaur DS, Thapliyal NC, Kishore S, Pathak VP. Efficacy of Broncho-Alveolar Lavage and Bronchial Brush Cytology in Diagnosing Lung Cancers. J Cytol. 2007;24:73–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmad M, Afzal S, Saeed W, Mubarik A, Saleem N, Khan SA, et al. Efficacy of bronchial wash cytology and its correlation with biopsy in lung tumours. J Pak Med Assoc. 2004;54:13–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang Y, Zhang X, Lu J, Haidong H. Application of liquid based cytology test of bronchial lavage fluid in lung cancer diagnosis. Thorac cancer. 2013;4:318–22. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox JT. Liquid-based cytology: Evaluation of effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and application to present practice. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2004;2:597–611. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2004.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Longatto-Filho A, Maeda MY, Erzen M, Branca M, Roteli-Martins C, Naud P, et al. Conventional Pap smear and liquid-based cytology as screening tools in low-resource settings in Latin America: Experience of the Latin American screening study. Acta Cytol. 2005;49:500–6. doi: 10.1159/000326195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akamatsu S, Kodama S, Himeji Y, Ikuta N, Shimagaki N. A comparison of liquid-based cytology with conventional cytology in cervical cancer screening. Acta Cytol. 2012;56:370–4. doi: 10.1159/000337641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kathiresan B, Iles S, Glinski L. Conventional cytology vs liquid based cytology in preparation of bronchial wash, does the later have potential advantages? Eur Respir J. 2013;42(Suppl 57):5091. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zardawi IM, Blight A, Ling S, Braye SG. Liquid based Vs Conventional cytology on respiratory material. Acta Cytol. 2009;53:481–3. doi: 10.1159/000325360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rana DN, O Donnel M, Malkin A, Griffin M. A comparative study: Conventional preparation and Thin Prep 2000 in respiratory cytology. Cytopathology. 2001;12:390–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2303.2001.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koivurinne KI, Shield PW. Thin layer preparation of dithiothretol treated bronchial washing specimens. Acta Cytol. 2003;47:637–44. doi: 10.1159/000326581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Astall E, Atkinson C, Morton N, Goddard MJ. The evaluation of liquid based CytoSED cytology of BAL specimens in the diagnosis of pulmonary neoplasia against conventional direct smears. Cytopathology. 2003;14:143–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2303.2003.00038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li D, Wan T, Su Y, Ding M, Wu J, Zhao Y. Liquid-based cytological test of samples obtained by catheter aspiration is applicable for the bronchoscopic confirmation of pulmonary malignant tumors. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:2508–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elsheikh TM, Kirkpatrick JL, Wu HH. Comparison of ThinPrep and Cytospin Preparations in the Evaluation of Exfoliative Cytology Specimens. Cancer. 2006;108:144–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]