Abstract

Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707 is a soil bacterium which is known for its capacity to aerobically degrade harmful organic compounds such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) using biphenyl as co-metabolite. Here we provide the first genetic and functional analysis of the KF707 respiratory terminal oxidases in cells grown with two different carbon sources: glucose and biphenyl. We identified five terminal oxidases in KF707: two c(c)aa3 type oxidases (Caa3 and Ccaa3), two cbb3 type oxidases (Cbb31 and Cbb32), and one bd type cyanide-insensitive quinol oxidase (CIO). While the activity and expression of both Cbb31 and Cbb32 oxidases was prevalent in glucose grown cells as compared to the other oxidases, the activity and expression of the Caa3 oxidase increased considerably only when biphenyl was used as carbon source in contrast to the Cbb32 oxidase which was repressed. Further, the respiratory activity and expression of CIO was up-regulated in a Cbb31 deletion strain as compared to W.T. whereas the CIO up-regulation was not present in Cbb32 and C(c)aa3 deletion mutants. These results, together, reveal that both function and expression of cbb3 and caa3 type oxidases in KF707 are modulated by biphenyl which is the co-metabolite needed for the activation of the PCBs-degradation pathway.

Keywords: biphenyl growth, gene expression, respiratory activities, terminal oxidases, Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707

Introduction

The bacterium Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707, isolated in the 1980s near a biphenyl (BP) manufacturing plant in Japan (Furukawa and Miyazaki, 1986), is known as one of the most effective aerobic degraders of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) (Fedi et al., 2001). Notably, these harmful and highly hydrophobic organic compounds are not primary substrates for cell growth so that a substrate such as biphenyl is required to support growth and induction of the PCBs degradation pathway (Furukawa and Miyazaki, 1986; Furukawa et al., 1993; Fedi et al., 2001). In this way, bacteria such as KF707 that are able to grow on biphenyl have the capacity to co-metabolize various PCBs congeners (Fedi et al., 2001). Despite the fact that most of the biphenyl degradation enzymes required for PCBs degradation are expressed during the aerobic growth of KF707 (Furukawa et al., 1993), no report is available on the functional arrangement of KF707 respiratory chain with biphenyl as carbon source. Indeed, an early biochemical study was published which aimed to define the effect of the toxic oxyanion tellurite on aerobic growth of KF707 in rich-medium (LB-broth) (Di Tomaso et al., 2002). This work suggested the presence in KF707 of a branched respiratory chain leading to two cytochrome (cyt) c oxidases and one cyanide insensitive quinol oxidase (CIO) (Di Tomaso et al., 2002). Since then no other studies on function and composition of the respiratory redox chain of this aerobic PCBs degrader have been published while in the meantime the expression and arrangement of the respiratory chains in species such as Pseudomonas (P.) putida PAK and P. aeruginosa PAO1, were elucidated (Kawakami et al., 2010; Arai, 2011; Sevilla et al., 2013; Arai et al., 2014). In strain PAO1 it was shown that the aa3 type oxidase, which plays a major role in aerobic respiration of several bacterial species (Poole and Cook, 2000), is expressed primarily under nutrient-limited conditions and is otherwise a minor player under nutrient-rich growth conditions, e.g., LB-broth (Kawakami et al., 2010). Conversely, two cbb3 type oxidases (Cbb31 and Cbb32) and a cyanide insensitive oxidase (CIO) are crucial when oxygen becomes limiting and during growth in biofilms (Comolli and Donohue, 2002, 2004; Alvarez-Ortega and Harwood, 2007; Kawakami et al., 2010). The Cbb31 oxidase is expressed constitutively while the Cbb32 is induced through oxygen limitation (Comolli and Donohue, 2004; Kawakami et al., 2010). Notably, mutation of the cco1 genes coding for the Cbb31 oxidase causes up-regulation of the CIO promoter in P. aeruginosa (Kawakami et al., 2010) indicating that the interactive regulation of the genes for Cbb3-1 and CIO is mediated by the redox-sensitive transcriptional regulator RoxSR (Bueno et al., 2012).

To fill the molecular and functional gap between our present knowledge of respiration in KF707 and the most investigated Pseudomonas spp., here we provide the first functional analysis of the KF707 respiratory genes (GenBank Acc. no. AP014862; Triscari-Barberi et al., 2012) in relation with two different primary carbon sources for growth such as glucose and biphenyl, while the remaining oxidative growth conditions were kept constant. This is an important aspect as the response of the central carbon catabolism to nutritional compounds is an absolute requirement for effective microbial colonization of a given environment (Rojo, 2010; Shimizu, 2014). Nevertheless, the modulation by the growth carbon source of the oxidative electron transport chain (ETC) that is the machinery which transduces into energy the reducing metabolic power, remains a puzzling issue (Dominguez-Cuevas et al., 2006; Nikel and Chavarria, 2015; Nikel et al., 2016).

Here we show that KF707 contains five different aerobic terminal oxidases: two of c(c)aa3 type (Caa3 and Ccaa3), two isoforms of cbb3 type (Cbb31 and Cbb32), and one bd type cyanide-insensitive quinol oxidase (CIO). However, while the function and expression of both Cbb31 and Cbb32 oxidases is prevalent in glucose grown cells as compared to other oxidases, the expression of Caa3 and Cbb32 oxidases were 4-fold increased and 7-fold decreased, respectively, when biphenyl was used as the sole carbon source along with a very low contribution to respiration of CIO. Furthermore, the respiratory activity and expression of CIO in glucose grown cells were up to 7 times higher in Cbb31 deletion mutant as compared to W.T. cells whereas this CIO up-regulation was not present in Cbb32 and C(c)aa3 deletion mutants.

This work not only reveals unexpected features of P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707 respiratory chain such as for example the presence of a Caa3 oxidase induced by growth in biphenyl but it also integrates the functional and genetic data obtained in the past with this PCBs-degrader (Taira et al., 1992; Furukawa et al., 1993; Fujihara et al., 2006; Tremaroli et al., 2007, 2008, 2010, 2011) allowing the establishment of solid molecular basis to better understand the use of toxic aromatics as energy and carbon source.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707, wild type (W.T.) and mutants, and Escherichia coli strains harboring cloning vectors and recombinant plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. Luria Bertani medium (LB), pH 7.2, was routinely used for bacterial growth. Trans-conjugants were selected on AB defined medium, pH 7.2, (K2HPO4, 3 g L−1; NaH2PO4, 1 g L−1; NH4Cl, 1 g L−1; MgSO4, 300 mg L−1; KCl 150 mg L−1, CaCl2, 10 mg L−1; FeSO4 7H2O 2.5 mg L−1) with D-glucose (5 g L−1) as carbon source. Antibiotics were added to KF707 and E. coli growth medium at the following concentrations: ampicillin (Amp), 50 μg mL−1, kanamycin (Km), 25 μg mL−1, gentamycin (Gm), 10 μg mL−1.

Table 1.

List of bacterial strains and plasmids, used in this study.

| Bacterial Strains | Relevant genotype | Source or References |

|---|---|---|

| P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707 | ||

| Wild type (W.T.) | Ampr | Furukawa and Miyazaki, 1986 |

| KFΔcox1 | Deletion of coxI-II-III, Ampr | This study |

| KFΔcox2 | Deletion of coxMNOP, Ampr | This study |

| KFΔcox1-2 | Deletion of coxI-II-III and coxMNOP, Ampr | This study |

| KFΔcco1 | Deletion of ccoN1O1Q1P1, Ampr | This study |

| KFΔcco2 | Deletion of ccoN2O2Q2P2, Ampr | This study |

| KFΔcco1-2 | Deletion of ccoN1O1Q1P1 and ccoN2O2Q2P2, Ampr | This study |

| KFΔcox1-2/cco1-2 | Deletion of coxI-II-III, coxMNOP, ccoN1O1Q1P1, and ccoN2O2Q2P2, Ampr | This study |

| KFΔCIO | Deletion of cioABC, Ampr | This study |

| KFΔcox1-2/CIO | Deletion of coxI-II-III, coxMNOP and cioABC, Ampr | This study |

| KFLac | KF707 lacZ with no insertion, Ampr | This study |

| KFcox1Lac | KF707 coxII::lacZ translational fusion, Ampr | This study |

| KFcox2Lac | KF707 coxM::lacZ translational fusion, Ampr | This study |

| KFcco1Lac | KF707 ccoN1::lacZ translational fusion, Ampr | This study |

| KFcco2Lac | KF707 ccoN2::lacZ translational fusion, Ampr | This study |

| KFCIOLac | KF707 cioA::lacZ translational fusion, Ampr | This study |

| KFΔcco1-2 CIOLac | Deletion of ccoN1O1Q1P1 and ccoN2O2Q2P2, cioA::lacZ translational fusion, Ampr | This study |

| KFΔcox1-2/cco1-2 CIOLac | Deletion of coxI-II-III, coxMNOP, ccoN1O1Q1P1 and ccoN2O2Q2P2, cioA::lacZ translational fusion Ampr | This study |

| KFΔcco1 CIOLac | Deletion of ccoN1O1Q1P1, cioA::lacZ translational fusion, Ampr | This study |

| KFΔcco2 CIOLac | Deletion of ccoN2O2Q2P2, cioA::lacZ translational fusion, Ampr | This study |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| DH5α | supE44, hsdR17, recA1, endA1, gyrA96, thi1, relA1 | Hanahan, 1983 |

| HB101 | Smr, recA, thi, pro, leu, hsdR | Boyer and Roulland-Dussoix, 1969 |

| Plasmids | Relevant genotype | Source or Reference |

| pRK2013 | Kmr, ori ColE1, RK2-Mob+, Rka-Tra+ | Figurski and Helinski, 1979 |

| pG19II | Gmr, sacB, lacZ, cloning vector and conjugative plasmid | Maseda et al., 2004 |

| pG19IIΔcox1 | Gmr, sacB, lacZ, carrying Δcox1 (coxI-II-III) deleted fragment | This study |

| pG19IIΔcox2 | Gmr, sacB, lacZ, carrying Δcox2 (coxMNOP) deleted fragment | This study |

| pG19IIΔcco1 | Gmr, sacB, lacZ, carrying Δcco1 (ccoN1O1Q1P1) deleted fragment | This study |

| pG19IIΔcco2 | Gmr, sacB, lacZ, carrying Δcco2 (ccoN2O2Q2P2) deleted fragment | This study |

| pG19IIΔCIO | Gmr, sacB, lacZ, carrying ΔCIO (cioABC) deleted fragment | This study |

| pTNS3 | RK6 replicon, encodes the TnsABC+D specific transposition pathway, helper plasmid DNA, Ampr | Choi et al., 2005 |

| pFLP2-Km | Flp recombinase-expressing plasmid, Apr, Kmr | Hoang et al., 1998 |

| pUC18-mini-Tn7T-Gm-lacZ | mini-Tn7, for construction of β-galactosidase protein fusions, lacZ, Gmr | Choi and Schweizer, 2006 |

| pUC-cox1-lacZ | Mini-Tn7T, coxII::lacZ translational fusion, Gmr | This study |

| pUC-cox2-lacZ | Mini-Tn7T, coxM::lacZ translational fusion, Gmr | This study |

| pUC-cco1-lacZ | Mini-Tn7T, ccoN1::lacZ translational fusion, Gmr | This study |

| pUC-cco2-lacZ | Mini-Tn7T, ccoN2::lacZ translational fusion, Gmr | This study |

| pUC-CIO-lacZ | Mini-Tn7T, cioA::lacZ translational fusion, Gmr | This study |

Names of KF707's deletion and translational fusion mutant strains were assigned based on Kawakami et al. (2010).

Growth curves of KF707 W.T. and mutant strains on different carbon sources (glucose and biphenyl) were conducted in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 50 mL of mineral salt medium (MSM), pH 7.2, at 30°C and 130 rpm (Tremaroli et al., 2010). A single colony of KF707 was first inoculated in 10 mL of LB medium and grown overnight, cells were centrifuged and washed twice with 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) then inoculated (1.0% v/v) on MSM medium supplemented with a single carbon source (biphenyl or glucose). Each carbon source was added to the sterile medium in order to have a final carbon concentration of 6 mM. Growth curves were performed by monitoring the OD600 level, every 2 h, until the late stationary phase (24 h for growth with glucose and 30 h for growth with biphenyl) was reached. Generation times (g) were calculated during the exponential growth phase. A one-way ANOVA was performed to test the null hypothesis that were no differences in the mean of g of the strains (see Text for details), followed by a two-sample T-test within pairs of strains.

Construction of KF707 terminal cytochrome oxidase deleted mutants

Nucleotide and amino acid sequences used in this study were based on the complete genome sequence of P. pseudolcaligenes KF707 available in GenBank under the accession no. AP014862. Sequence similarity searches were performed using BLAST software (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) (Altschul et al., 1990) together with the conserved domain database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) while multiple sequence alignments were performed with ClustalW software (Thompson et al., 1994). The accession numbers of the genes mentioned in this paper are summarized in Table S2 of the Supplementary Material or directly reported in the text.

KF707 deleted mutants for single or multiple oxidases (Table 1) were obtained by Gene SOEing PCR technique (Izumi et al., 2007). For the construction of recombinant sequences with deletion in specific genes the primer pairs for the amplification of the upstream flanking region, and the primer pairs for the amplification of the downstream flanking region, were used (Table S1). The outer primers, specifically the forward for the upstream region and the reverse for the downstream one, were designed with specific restriction sites (Table S1). The inner primers, specifically the reverse for the upstream region and the forward for the downstream one, included overlapping sequences in order to join the flanking regions together as described previously (Izumi et al., 2007) (Table S1).

The recombinant sequences with the deletion genes obtained by the SOEing method, were double digested and cloned in specific restriction sites of the conjugative plasmid pG19II in order to construct pG19IIΔcox1, pG19IIΔcox2, pG19IIΔcco1, pG19IIΔcco2, and pG19IIΔCIO (Table 1) (Maseda et al., 2004). Recombinant plasmids were introduced into chemically competent cells of E. coli DH5α host and transformants were selected for Gm resistance along with white/blue screening by adding X-gal to agar media at a final concentration of 40 μg mL−1. E. coli DH5α, containing each pG19II recombinant plasmid, was used as donor strain and plasmid was transferred by tri-parental conjugation to the recipient KF707 wild type strain by means of the helper strain E. coli HB101 pRK2013. The conjugation included two steps of homologous recombination. The first crossover recombination results in integration of the recombined pG19II plasmid into the genome, transconjugants were selected for their resistance to Gm and sensitivity to sucrose (Maseda et al., 2004). After the second single crossover recombination, only the cells that had lost pG19II were selected by growth in the presence of 20% sucrose; their phenotype at the end result was Gm sensitive and sucrose resistance (Maseda et al., 2004). Deletion mutants were confirmed by PCR and sequencing analysis.

Construction of KF707 lacZ translational fusion mutants

To evaluate the activity of terminal oxidases in KF707, β-galactosidase assays were performed by using mutant strains containing translational fusions of the terminal oxidases with lacZ gene. The lacZ-containing strains were constructed by utilizing a Tn7-based method and the translational fusion fragments were inserted into the genome of KF707 at the attTn7 site located downstream of glmS (Choi and Schweizer, 2006).

The promoter region, the ATG start codon and the coding region for the first 10 amino-acids, of coxII (cox1 gene cluster—KFcox1Lac), coxM (cox2 gene cluster—KFcox2Lac), ccoN1 (cco1 gene cluster—KFcco1Lac), ccoN2 (cco2 gene cluster—KFcco2Lac), and cioA (cio gene cluster—KFCIOLac) were amplified by PCR, using primers in the Table S1. These fragments were cloned into the pUC-miniTn7-Gm-lacZ vector and the resultant plasmid were electroporated, with the helper plasmid pTNS3 (Choi et al., 2005), into KF707. Then the mutant strains were obtained with the method described by Kawakami et al. (2010).

Finally, β-galactosidase assays were performed at 30°C in MSM minimal medium with glucose or biphenyl as single carbon source, at two different phases of growth (exponential phase—OD600 nm 0.3–0.5 and stationary phase—OD600 nm 0.7–0.9) using a standard protocol (Sambrook et al., 1989); each experiment was repeated at least six times.

Enzymatic activities with NADI assay

To observe the cytochrome c oxidases activity in intact cells of W.T. and mutant strains, a NADI assay was carried out (Marrs and Gest, 1973). KF707 strains were grown until the stationary phase (OD600 nm 0.7–0.9), in minimal medium (MSM) with glucose or biphenyl as single carbon source. 1 mL of culture was collected, centrifuged and washed twice with 1 ml of Tris-HCl 10 mM (pH 7.5). Subsequently, 100 μL of a 1:1 mixture of 35 mM α-naphthol, in ethanol, and 30 mM N,N-dimetyl-p-phenylenediamine monohydrochloride (DMPD), in water, was added to the cells. The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for a few seconds and the color change was observed within 1 min.

Preparation of membrane fragments

For the preparation of membrane fragments, cells were grown aerobically until the stationary phase (OD600 nm 0.7–0.9) in 3 L Erlenmeyer flasks containing 1 L of mineral salt medium (MSM), pH 7.2 at 30°C and 130 rpm, with 6 mM of glucose or biphenyl as single carbon source. Growths were stopped after 16 and/or 30 h for glucose or biphenyl medium, respectively. Cells were washed twice with 0.1 M phosphate buffer to reach about 1.6 g of wet weight cells. Membrane fragments for respiratory activities and spectroscopic analysis were obtained using French pressure cell and ultracentrifugation, in 50 mM MOPSO buffer (pH 7.2) containing 5 mM MgCl2 (Di Tomaso et al., 2002). Membranes were suspended at a known protein concentration (5–10 mg mL−1) in the same buffer and used immediately for analysis. Experiments were conducted in membranes of W.T. and mutant cells from at least two/three independent cell preparations (see Figure and Table legends).

Spectroscopic analyses, respiratory activities, and protein determination

The amounts of cytochromes in membrane fragments were estimated by recording reduced (with 0.5 mM NADH plus 5 mM KCN and/or a few crystals of sodium dithionite)-minus-oxidized [with a few crystal(s) of potassium ferricyanide] optical difference spectra at room temperature with a Jasco 7800 spectrophotometer. Absorption coefficients ϵ603−630 of 11.6 mM−1 cm−1, ϵ561−575 of 22 mM−1 cm−1, and ϵ551−542 of 19.1 mM−1 cm−1 were used to determine the amounts of a-, b-, and c-type cytochromes, respectively (Kishikawa et al., 2010).

Respiratory activities in membrane fragments isolated from KF707 W.T. and deletion mutant strains, were determined by monitoring the oxygen consumption with a Clark-type oxygen electrode YSI 53 (Yellow Springs Instruments) as described previously (Daldal et al., 2001). Activities in the presence or absence of specific inhibitors (see Text for details) were measured within a few hours after the end of the membrane isolation procedure. The inhibitory concentration IC50 was the concentration of an inhibitor required to inhibit 50% of the target enzymatic activity.

Protein content of samples was determined using the Lowry assay with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard (Lowry et al., 1951).

Results

Putative genes for terminal oxidases

The aa3 type cytochrome oxidases of KF707

The analysis of the P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707 complete genome shows the presence of two gene clusters for two different cox oxidases of aa3 type whose subunits are predicted to contain c-type hemes: caa3 and ccaa3 type oxidases. The caa3 type oxidase is encoded by coxI-II-III (BAU71738-71737-71740) gene cluster (Figure 1; Table S2). The three subunits, which are annotated as part of aa3 type cytochrome c oxidase in the KF707 genome, have sequences with high similarity (~90%) to CoxB, CoxA, and CoxC of P. aeruginosa (Stover et al., 2000). Similarly to P. aeruginosa, subunit I (58.8 KDa) of KF707 is predicted to carry a low spin a-type heme and one heme a3-CuB binuclear catalytic center. The predicted subunit II (42 KDa) consists of a membrane anchored cupredoxin domain, containing the electron-accepting homo-binuclear copper-center, CuA, with a carboxy-terminal fusion to a cytochrome c domain (Lyons et al., 2012). The presence of a c-type heme in the aa3 type oxidase of KF707 was suggested by an alignment analysis (Supplementary Material—Alignment 1) which showed, in the C-terminal region, the typical amino-acids residues (Cxx-CH), that coordinate the heme c in Thermus thermophilus and Rhodothermus marinus caa3 oxidases (Lyons et al., 2012); these characteristic residues are absent from Rhodobacter sphaeroides and Paracoccus denitrificans aa3 oxidases while the CoxII amino acid sequence of KF707 has 81% similarity with the CoxB of P. aeruginosa PAO1.

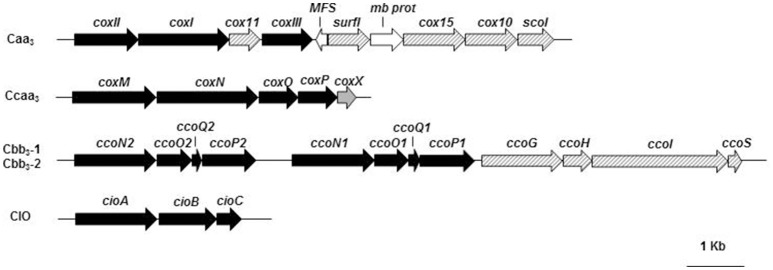

Figure 1.

Organization of the terminal oxidase gene clusters in KF707: cox, encoding for cytochrome c oxidases of caa3type (coxI-II-III) and ccaa3type (coxMNOP); cco, encoding for gene products involved in the synthesis and assembly of two cytochrome c oxidases of cbb3type (ccoN1O1Q1P1 and ccoN2O2Q2P2); cio, gene cluster for the quinol oxidase CIO (cioABC). Genes (listed in Table S2) are represented by arrows and by different colors or stripes: black, functional genes; dashed stripes, genes for cytochrome biogenesis; gray, cytochrome c oxidase accessory membrane protein (CoxX); white, genes supposedly not directly related with the gene clusters under analysis. Full names and abbreviations used: MFS, Major Facilitator Superfamily permease; mb prot, membrane protein.

In KF707 an additional ccaa3 type oxidase is predicted to be encoded by the gene cluster coxMNOP (BAU74428-74432) (Figure 1; Table S2). Sequence analyses showed that this alternative complex is characterized by the organization which is typical of aa3 type cytochrome oxidases present in Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021, Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34, Mesorhizobium sp., and Polaromonas (Preisig et al., 1996b). Previous studies have shown that the coxMNOP gene cluster encodes a complex with homology to Cu-containing cyt c oxidase; indeed it was observed that the subunit I (66 KDa), encoded by coxN, was very similar to CoxA of P. aeruginosa (Bott et al., 1992) and to CoxI of KF707's caa3. The alignment suggested that CoxM (52 KDa) of KF707 showed, in the C-terminal portion, two c-type hemes (Supplementary Material—Alignment 2) and therefore this oxidase is a ccaa3 cytochrome oxidase; in this case, in the C terminal portion, there is a repetition of the residues (Cxx-CH) that coordinate the c-type hemes. These enzymes are not common, but they have also been found in bacteria such as Desulfovibrio vulgaris (Lobo et al., 2008) and Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 (Le Laz et al., 2014). In KF707 CoxP and CoxO amino acid sequences are homologs to subunit III of the aa3 complex.

The cbb3 type oxidases of KF707

Two complete sets of genes encoding cyt c oxidases of cbb3 type (Cbb31 and Cbb32) are present in KF707 (Figure 1; Table S2). These genes, tandemly clustered in the genome of KF707, are situated in the ccoN1O1Q1P1 (BAU73552-73555) and ccoN2O2Q2P2 (BAU73556-73559) clusters as previously shown in P. aeruginosa strains PAO1 and PA7, P. putida KT2440, and P. fluorescens (Stover et al., 2000). Similarly to orthodox cbb3 type oxidases, the catalytic subunit I (~50 KDa) of KF707 encoded by ccoN gene is expected to comprise 12 transmembrane helices and to contain, in addition to the low spin b-type heme, a binuclear center formed by high spin b3 heme and CuB. In general, the two trans-membrane cytochrome c subunits with c-type monoheme and diheme groups are encoded by the genes ccoO (~22 KDa) and ccoP (~40 KDa) respectively, while CcoQ (~7 KDa) are necessary for the stability of the complex. These oxidases utilize cytochrome c as an electron donor and they lack a CuA site.

In general, the ccoNOQP operons encoding cbb3 oxidase subunits are found in association with the ccoGHIS (BAU73548-73551) gene cluster which is located in the downstream region and whose expression is required for the maturation and assembly of a functional cbb3 oxidase and this type of gene organization is also present in KF707 (Figure 1; Table S2) (Preisig et al., 1996a; Koch et al., 2000; Pitcher and Watmough, 2004). Homology searching of both ccoNOQP and ccoGHIS, showed the same gene arrangement among P. aeruginosa strains PAO1 and PA7, P. putida KT2440, and P. entomophila L48 while P. aeruginosa strains UCBPP-PA14 and LESB58, P. stutzeri A1501, and P. mendocina YMP showed similar features except that some of them lack one copy of the ccoQ gene.

The cyanide-insensitive oxidase of KF707

In the past, an oxidase activity insensitive to cyanide (CIO), which accounts for ~20% of the total NADH-dependent respiration of LB-grown KF707 cells, has been reported (Di Tomaso et al., 2002). Here we show that KF707 genome contains two genes coding for two subunits which are highly similar to those of cytochrome bd type quinol oxidases of Pseudomonas fulva 12-X and P. mendocina (Figure 1; Table S2). In E. coli and other Gram negative bacteria, the cyt bd-I complex consists of two subunits named CydA (subunit I) and CydB (subunit II), while in Pseudomonas spp. it is encoded by the cioA and cioB genes, respectively (Cunningham et al., 1997). In KF707, genes cioA (BAU72498) and cioB (BAU72499) code for two orthodox subunits in addition to a third accessory subunit encoded by cioC (BAU72500).

The bd oxidase functions as a quinol oxidase with a relatively low sensitivity to cyanide and it shows often high affinity for oxygen (D'mello et al., 1996). CIO contains low-spin heme b558, high spin heme b595 and heme d (Jünemann, 1997; Siletsky et al., 2016). It should be noted that although both the cioA and cioB genes are highly similar to the cydAB genes encoding a bd-type oxidase, the CIO from KF707 lacks the spectral features of hemes b595 and heme d (Matsushita et al., 1983; Di Tomaso et al., 2002) (not shown).

Expression of membrane bound oxidases

Early biochemical results have shown that membranes isolated from KF707 cells grown in LB-growth medium do not contain significant amounts of aa3 type hemes (Di Tomaso et al., 2002). However, since KF707 is capable to aerobically degrade PCBs in the presence of biphenyl as co-metabolite (Abramowicz, 1990) we thought to determine the expression of the entire set of the putative genes for terminal oxidases in cells grown in biphenyl as compared to cells grown on a defined carbon source such as glucose.

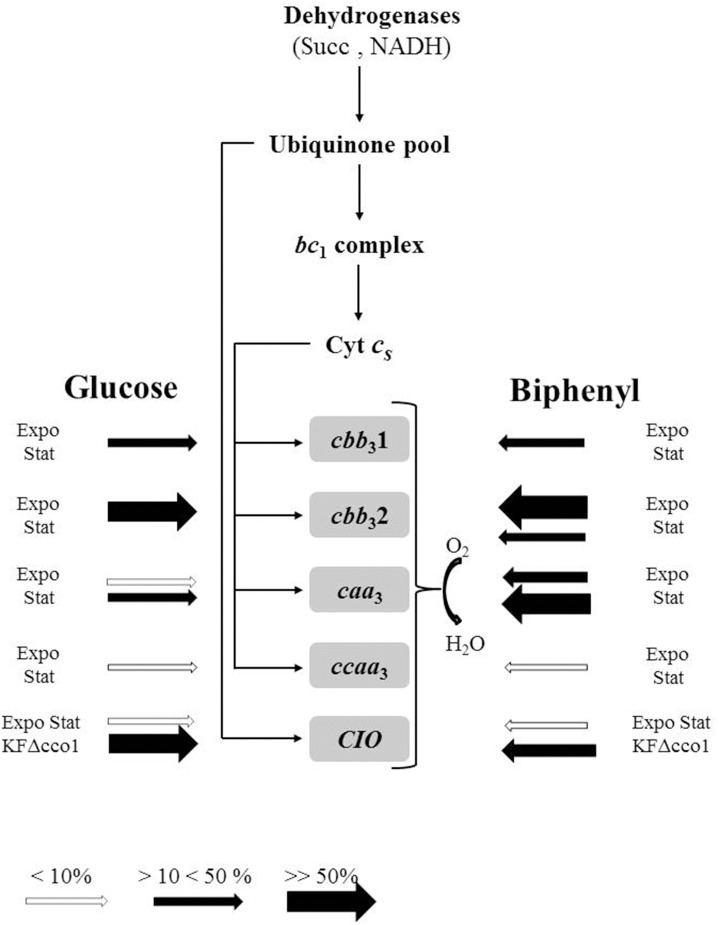

The expression pattern in response to the carbon source was determined using lacZ translational fusions that monitor the promoter activities at the translational level. Figure 2 shows the β-galactosidase activity of each translational fusion when KF707 cells were cultured in glucose and biphenyl medium and harvested at the same cell density in their exponential and stationary growth phases.

Figure 2.

β-Galactosidase activities measured in cell extracts derived from the KF707 translational fusion mutant strains (Table 1), grown aerobically in MSM medium with glucose (A) and biphenyl (B) as sole carbon source. The assays were performed (at least six times) at two different stages of growth (exponential phase OD600 nm 0.3–0.5 and stationary phase OD600 nm 0.7–0.9) and the activities are presented as percentage of total activity. Error bars indicate standard deviation of the means. Asterisks indicate that mean values are significantly different according to one-way ANOVA and verified by a two samples T-test within pairs of strains (**p < 0.01).

The cco1 promoter for the Cbb31 exhibited similar basic level of expression in both exponential and stationary phases in cells grown with glucose (Figure 2A). Using the same carbon source, the cco2 promoter for the Cbb32 showed a high activity in both exponential and stationary phases of growth. In contrast to cco2, the cox1 promoter for the Caa3 oxidase had a low activity in cells harvested at their exponential growth phase while an activity similar to that of the cco1 promoter was seen in the stationary growth phase. The cox2 promoter for the Ccaa3 and the cio promoter for the CIO oxidase showed very low activities in both exponential and/or stationary grown cells.

In cells grown with biphenyl (Figure 2B) the cco1 promoter exhibited similar levels of expression in both exponential and stationary growth phases. In contrast to cco1, the cco2 promoter showed a high expression level in the exponential phase while cco2 expression was very low in the stationary phase of growth. Interestingly, the drop of cco2 expression in stationary phase was matched with a drastic increase of cox1 expression which was 4- and 10-times higher than that seen in the exponential growth phase on biphenyl and glucose, respectively. Similarly to cells grown in glucose, the cox2 and the cio promoters of cells grown in biphenyl showed very low expression values in both exponential and stationary growth phases.

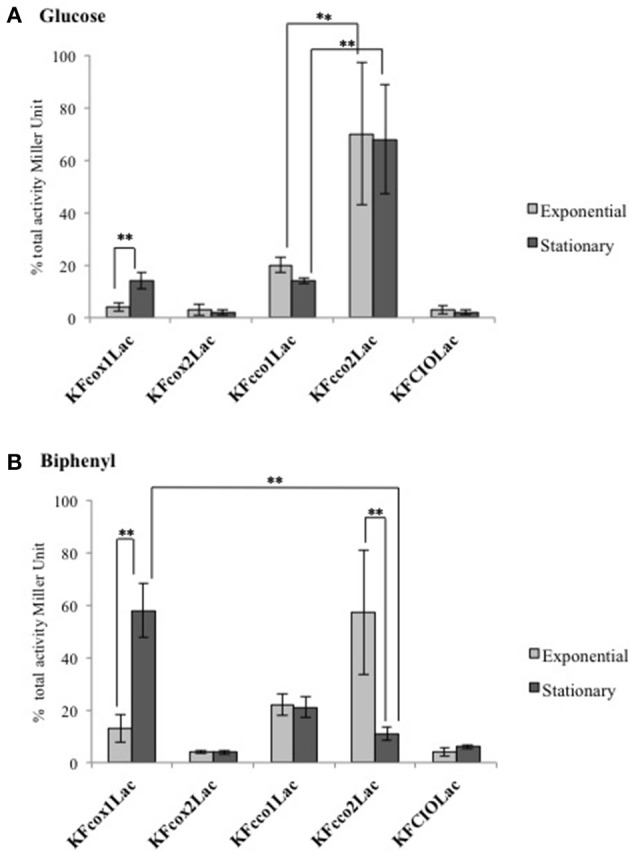

Growth profiles and NADI assay

KF707 W.T. and seven terminal oxidase mutant strains, namely: KFΔcox1-2 (Caa3 and Ccaa3 minus), KFΔcco1-2 (Cbb31 and Cbb32 minus), KFΔcox1-2/cco1-2 (Cbb31, Cbb32, Caa3, and Ccaa3 minus), KFΔCIO (CIO minus), KFΔcox1-2/CIO (Caa3, Ccaa3, and CIO minus), KFΔcco1 (Cbb31 minus), and KFΔcco2 (Cbb32 minus), were tested for their capacity to grow aerobically with glucose or biphenyl as sole carbon source. As shown in Figure 3, the KFΔcco1-2 and KFΔcox1-2/cco1-2 mutant strains were clearly impaired in their aerobic growth profiles and generation times (g) in glucose (g = 76 ± 1.5 and 88 ± 1.5 min, respectively; p ≤ 0.05) as compared to W.T. (g = 63 ± 0.8 min; p ≤ 0.05). Similarly, KFΔcco1-2 and KFΔcox1-2/cco1-2 mutant strains were shown to grow slowly in biphenyl (g = 140 ± 21 and 147 ± 26 min, respectively; p ≤ 0.05) as compared to W.T. (g = 97 ± 8.5 min; p ≤ 0.05). The results also indicated that the KFΔcox1-2 and KFΔCIO mutant growth curves were similar to KF707 W.T. growth curve regardless of the carbon source used for growth although a slight but significant increase of the generation time was seen in KFΔCIO cells grown in glucose and biphenyl (g = 75 ± 1.4 and 113 ± 1.5 min, respectively; p ≤ 0.05). The specific contribution of Cbb31 and Cbb32 to cell growth was also examined (Figure S1). The growth curves show that the lack of the Cbb31 oxidase impaired the growth rate in both glucose (g = 85 ± 0.4 min; p ≤ 0.05) and biphenyl (g = 151±1.7 min; p ≤ 0.05) while the lack of Cbb32 oxidase did not significantly affect the growth with both carbon sources (g = 75 ± 5 min and 110 ± 4.4, respectively). These results, taken together, indicate that the KF707 optimal growth rates in glucose or biphenyl depend on the simultaneous presence of both cbb3 type oxidases along with that of the CIO oxidase. This conclusion is also supported by evidence that despite numerous efforts, it was not possible to obtain a triple oxidase mutant lacking the CIO, Cbb31, and Cbb32 oxidases, so to suggest that this triple mutant was not viable under the tested aerobic growth conditions.

Figure 3.

Growth curves of KF707 W.T. and deletion mutant strains (Table 1). Strains were grown in 50 mL of MSM medium in 250 mL flasks shaken at 130 r.p.m, with 6 mM of glucose (A) or biphenyl (B). The optical densities were observed at 600 nm every 2 h. Growths were stopped at late-stationary phase, after 16 and 30 h, respectively for medium containing glucose or biphenyl.

In addition to growth curves, KF707 W.T. and deletion mutant phenotypes were tested through the use of the NADI assay (Figure S2). This assay aims to visualize the cytochrome c oxidase respiration following the time-course oxidation of the artificial electron donor N,N,dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine (DMPD) which appears colorless in its reduced state or blue when it is oxidized to indophenol. With cells grown on glucose the assay was negative only in the case of KFΔcco1-2 and KFΔcox1-2/cco1-2 mutants, suggesting a negligible activity of c(c)aa3 type oxidases. On the contrary, in cells grown on biphenyl the assay was negative only in the case of KFΔcox1-2/cco1-2, suggesting a functional role of the caa3 type oxidase with biphenyl as the carbon source.

Spectroscopic analysis and respiratory activities

Table 2 and Figure S3 summarize the heme-spectroscopic features of membranes isolated from cells grown in glucose as compared to those from cells grown in biphenyl and harvested at their stationary phase of growth. The spectroscopic evaluation of membranes from glucose grown cells showed that the α band attributable to aa3 type hemes is barely detectable at 600–605 nm. Conversely an evident peak at 600–605 nm which is attributable to aa3 type heme (Table 2) was seen in KF707 membranes from cells grown on biphenyl (Figure S3). This observation is therefore in line with the gene expression values reported in Figure 2B showing that the cox1 promoter activity for the Caa3 oxidase is 4-times enhanced in KF707 biphenyl grown cells harvested in their stationary phase. The spectroscopic results of Table 2 also indicate that the protein subunits encoded by the gene clusters cox123, coxMNOP, ccoN1O1Q1P1, and ccoN2O2Q2P2 (Table S2) all contain considerable amounts of c-type hemes as predicted by BLASTP search. Indeed, the amount of c-type heme as detected at 551–542 nm, decreased in KFΔcox1-2 and/or KFΔcco1-2 mutants and even more drastically in KFΔcox1-2/cco1-2 mutant cells (Figure S3).

Table 2.

Heme amounts of a-, b-, and c-type in membranes isolated from KF707 W.T. and oxidase mutant cells grown with glucose and/or biphenyl as unique carbon source.

| Carbon source | Strain | c-type heme e 551−540 = 19.1 (nmoles/mg protein) | b-type heme e 561−575 = 22 (nmoles/mg protein) | a-type heme e603−630 = 11.6 (nmoles/mg protein) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLUCOSE | KF707 W.T. | 1.65 ± 0.20 | 0.77 ± 0.08 | 0.10 ± 0.05 |

| KFΔcox1-2 | 1.50 ± 0.20 | 0.80 ± 0.09 | n.d. | |

| KFΔcco1-2 | 0.95 ± 0.15 | 0.62 ± 0.07 | 0.12 ± 0.05 | |

| KFΔcox1-2/cco1-2 | 0.74 ± 0.10 | 0.64 ± 0.07 | n.d. | |

| KFΔCIO | 1.42 ± 0.15 | 0.84 ± 0.10 | 0.12 ± 0.05 | |

| KFΔcox1-2/CIO | 1.09 ± 0.12 | 0.61 ± 0.07 | n.d. | |

| BIPHENYL | KF707 W.T. | 1.80 ± 0.20 | 0.87 ± 0.10 | 0.45 ± 0.03 |

| KFΔcox1-2 | 1.10 ± 0.09 | 0.82 ± 0.10 | n.d. | |

| KFΔcco1-2 | 0.86 ± 0.07 | 0.59 ± 0.06 | 0.27 ± 0.02 | |

| KFΔcox1-2/cco1-2 | 0.65 ± 0.08 | 0.32 ± 0.01 | n.d. | |

| KFΔCIO | 0.78 ± 0.09 | 0.50 ± 0.03 | 0.30 ± 0.02 | |

| KFΔcox1-2/CIO | 0.81 ± 0.07 | 0.55 ± 0.03 | n.d. |

Symbols and abbreviations used: n.d., not-detectable by optical spectroscopy at room temperature. Values are the mean of at least two membrane preparations from different cell growth cultures for each strain. Mutant phenotype strains abbreviations as in Table 1. See Materials and Methods for experimental details.

Oxidases of aa3 and cbb3 heme type are thought to function as cytochrome c oxidases whereas CIO was characterized as a quinol oxidase (Cramer and Knaff, 1990). In the past it was shown that both cbb3 and aa3 type oxidases in R. sphaeroides membranes were inhibited by cyanide (CN−) and azide () anions (Daldal et al., 2001). However, while 50 μM CN− fully inhibited both the cbb3 and aa3 type cytochrome c oxidase activities, 50 μM only inhibited the cbb3 dependent activities. Thus, in the presence of 50 μM cyanide or azide it was possible to determine the contribution of aa3 type and/or cbb3 type oxidases to the total respiratory activity catalyzed by cytochrome c oxidases (Daldal et al., 2001). Here, the same inhibitor concentration was used to estimate the activities of KF707 Cbb3 and C(c)aa3 oxidases in the presence or absence of cyanide and azide in membrane obtained from W.T. and mutant cells grown with glucose and biphenyl (Tables 3, 4).

Table 3.

Respiratory activities in membranes from KF707 W.T. and oxidase mutant cells grown, until the stationary phase (OD600 nm) 0.7–0.9, in glucose (Gc) as sole carbon source.

| Electron donors | NADH | ASCORBATE | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additions | / | CN− | Cyt C | TMPD | TMPD/ | TMPD/CN− | |

| STRAINS | |||||||

| KF707 W.T. | 165 ± 10 | 72 ± 3.3 | 29 ± 5.0 | 33 ± 1.0 | 157 ± 20 | 32 ± 3.0 | 7.0 ± 2.0 |

| KFΔcox1-2 | 178 ± 20 | 38 ± 8.0 | 34 ± 10 | 59 ± 6.0 | 221 ± 14 | 21 ± 2.5 | 16 ± 1.0 |

| KFΔcco1-2 | 175 ± 7.0 | 160 ± 2.0 | 125 ± 1.0 | 9 ± 0.5 | 38 ± 5.0 | 32 ± 3.3 | 8.0 ± 1.0 |

| KFΔcox1-2/cco1-2 | 174 ± 15 | 172 ± 15 | 167 ± 15 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 11 ± 2.0 | 11 ± 2.0 | 11 ± 2.0 |

| KFΔCIO | 145 ± 30 | 29 ± 5.0 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 37 ± 3.5 | 208 ± 31 | 35 ± 3.5 | 10 ± 0.5 |

| KFΔcox1-2/CIO | 145 ± 5.0 | 25 ± 5.0 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 45 ± 7.0 | 163 ± 12 | 10 ± 2.5 | 10 ± 2.5 |

| KFΔcco1 | 196 ± 7.0 | 165 ± 2.0 | 110 ± 3.0 | 26 ± 2.5 | 124 ± 5.0 | 12 ± 3.0 | 3.0 ± 1.0 |

| KFΔcco2 | 220 ± 10 | 78 ± 5.0 | 51 ± 5.0 | 33 ± 2.5 | 145 ± 5.0 | 37 ± 3.5 | 9.0 ± 2.0 |

Symbols and abbreviations used: , sodium azide (30 μM); CN−, potassium cyanide (50 μM); Cyt C, horse-heart cytochrome C (50 μM); TMPD, N,N,N′,N′-Tetramethyl-p-phenylene diamine (50 μM). Mutant phenotype strains abbreviations as in Table 1. Rates, expressed as nmoles of O2 consumed min−1 mg of proteins−1, are the mean of at least two/three membrane preparations from independent cell cultures.

Table 4.

Respiratory activities in membranes from KF707 W.T. and oxidase mutant cells grown, until the stationary phase (OD600 nm) 0.7–0.9, in biphenyl (Bp) as sole carbon source.

| Electron donors | NADH | ASCORBATE | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additions | / | CN− | CytC | TMPD | TMPD/ | TMPD/CN− | |

| STRAINS | |||||||

| KF707 W.T. | 111 ± 2.5 | 64 ± 9.5 | 7.0 ± 0.3 | 37 ± 2.0 | 165 ± 13 | 88 ± 15 | 7.0 ± 2.0 |

| KFΔcox1-2 | 38 ± 5.0 | 9.0 ± 3.3 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 17 ± 3.0 | 75 ± 10 | 5.0 ± 2.0 | 3.0 ± 2.0 |

| KFΔcco1-2 | 96 ± 9.3 | 80 ± 12 | 29 ± 0.4 | 18 ± 3.0 | 117 ± 12 | 108 ± 5.0 | 6.0 ± 1.7 |

| KFΔcox1-2/cco1-2 | 36 ± 5.0 | 35 ± 5.0 | 35 ± 5.0 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 6.0 ± 2.5 | 6.0 ± 2.5 | 6.0 ± 2.5 |

| KFΔCIO | 83 ± 4.0 | 60 ± 5.0 | 4.0 ± 2.0 | 37 ± 0.4 | 174 ± 1.0 | 110 ± 5.0 | 12 ± 1.0 |

| KFΔcox1-2/CIO | 104 ± 4.0 | 15 ± 2.5 | 3.5 ± 1.5 | 8.3 ± 3.5 | 67 ± 1.0 | 9.3 ± 2.0 | 8.3 ± 2.0 |

| KFΔcco1 | 111 ± 8.0 | 97 ± 7.0 | 37 ± 2.0 | 20 ± 2.5 | 201 ± 18 | 150 ± 15 | 20 ± 7.0 |

| KFΔcco2 | 95 ± 5.0 | 46 ± 5.0 | 11 ± 3.0 | 25 ± 3.0 | 200 ± 20 | 114 ± 13 | 13 ± 5.0 |

Symbols and abbreviations used: , sodium azide (30 μM); CN−, potassium cyanide (50 μM); CytC, horse heart cytochrome C (50 μM); TMPD, N,N,N′,N′-Tetramethyl-p-phenylene diamine (50 μM). Mutant phenotype strains abbreviations as in Table 1. Rates, expressed as nmoles of O2 consumed min−1 mg of protein−1, are the mean of at least two/three membrane preparations from independent cell cultures.

Table 3 shows that with NADH as an electron donor, the total oxygen consumption by KF707 W.T. membranes from cells grown in glucose (hereafter named Gcm) was 66% inhibited by 50 μM azide (contribution of cbb3 oxidases) while only a further 17% was inhibited by 50 μM cyanide [contribution of C(c)aa3 oxidases]. The NADH oxidation when measured in membranes from biphenyl grown cells (hereafter named Bpm) (Table 4), was 42% inhibited by 50 μM azide while a further 52% of the total respiration was sensitive to 50 μM cyanide. Apparently, the % contribution to the NADH respiration of C(c)aa3 oxidases that are resistant to 50 μM azide but sensitive to 50 μM cyanide, was 3-fold higher in Bpm (52%) than in Gcm (17%). In line with this, the ascorbate/TMPD oxidase activity which indicates the overall oxygen consumption catalyzed by cytochrome c oxidases, was 80 and 47% repressed by azide in Gcm and Bpm, respectively, confirming the main role of cbb3 type oxidases in Gcm but not in Bpm. Results in W.T. membranes were confirmed by activities determined in membranes from oxidase mutant cells, with some additional finding, namely: the lack of both Cbb31 and Cbb32 oxidases (KFΔcco1-2 mutant) resulted into a strong activation of CIO dependent activity in Gcm (72% resistant to CN−). Further, the CIO activation resulting from the lack of cbb3 oxidases was less evident in Bpm (30% resistant to CN−) in which 83% of the NADH activity was insensitive to azide confirming the main functional role of caa3 type oxidase using biphenyl carbon source (see also Figure 2). Accordingly, in Bpm-KFΔcco1-2 the ascorbate/TMPD oxidation was only 8% inhibited by azide while 95% was sensitive to cyanide (see also Figure S2, NADI assay). These data, taken together, allowed us to determine in Gcm-KFΔcox1-2 and Bpm-KFΔcco1-2 the IC50 for cyanide of Cbb3 and C(c)aa3 oxidase activities which were in the order of 4.10−7 M CN− and 5.10−6 M CN−, respectively (Materials and Methods and Figure S4).

As expected by the preceding results, both activation and functional role of CIO in supporting NADH dependent respiration in Gcm was also seen in the quadruple oxidase mutant KFΔcox1-2/cco1-2 whose respiratory activity was 100% insensitive to 50 μM cyanide; further, the latter oxidative activity was catalyzed by CIO with a rate similar to that performed by W.T. membranes in the absence of inhibitors. Bpm-KFΔcox1-2/cco1-2was therefore used to determine the IC50 for cyanide of CIO to be close to 1 mM CN− (Figure S4).

To better understand the lack of which of the two Cbb3 oxidases determines an activation of the CIO oxidase activity, and the contribution of each Cbb3 oxidase to the total respiration, the oxygen consumptions in membranes from KFΔcco1 (Cbb31 minus) and/or KFΔcco2 (Cbb32 minus) mutant cells grown in glucose or biphenyl, were determined. Results in Table 3 (bottom lines) show that in glucose grown cells the CIO catalyses 56% of the total respiration of KFΔcco1, being 3–4 times higher than the corresponding activity measured in KFΔcco2 and W.T. membranes, with a parallel minor role (16%) of the Cbb32 oxidase. Differently, in KFΔcco2 membranes the Cbb31 oxidase catalyses 65% of the total respiration compensating the low CIO activity. Accordingly, the β-galactosidase assays performed in KFΔcco1CIOLac and KFΔcco2CIOLac cell extracts indicated that the expression of CIO in KFΔcco1 increases 4 times as compared to that of KFΔcco2 (Figure S5). Interestingly, results in Table 4 (bottom lines) show that in biphenyl grown cells the CIO catalyses 33% of the total CN− resistant NADH respiration of KFΔcco1 with a parallel minor role of the Cbb32 oxidase (13%, see also Figure S5) and a prevalent contribution of the Caa3 oxidase (54%) to respiration. Notably, in KFΔcco2 the CIO activity decreased to 13% of the total NADH oxidation with a parallel increase of the contribution to respiration of Cbb31 (43%) and Caa3 (43%) oxidases.

One consideration arising from the results of Tables 3, 4 concerns the low values obtained from measurements of cytochrome oxidase activities using horse-heart cytochrome c (HHCyt c) as electron donor. This activity, in either Gcm or Bpm was ~5–6 times lower than that measured with TMPD as electron donor suggesting the low capacity of soluble HHCyt c to reduce KF707 respiratory oxidases which are featured by c-type hemes as catalytic subunits. This finding contrasts with the capacity of HHCyt c to replace the soluble mono-heme cyt c2 which is the physiological electron donor to either aa3 or cbb3 type oxidases in R. sphaeroides (Daldal et al., 2001). Conversely, our observation in KF707 is in line with an early report in which it was shown that HHCyt c was a poor substrate for the cbb3 type oxidase activity of V. cholera. In this latter species, the rate of oxygen reduction with HHCyt c was several fold lower than with the soluble di-heme cyt c4 which was identified as the physiological electron donor to the Cbb3 oxidase (Chang et al., 2010) (see Discussion).

Discussion and conclusions

The branched respiratory chain of P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707

Terminal cytochrome oxidases

In the past, the heme-copper oxygen (HCO) reductases were classified into three families: (1) type A or mitochondrial like oxidases of aa3 type; (2) type B or ba3 type oxidases; and (3) type C or cbb3 type oxidases which are only detected in bacteria (Sousa et al., 2012). Additionally, cyt bd type oxidases which are phylogenetically unrelated to HCO, represent a second major superfamily (Jünemann, 1997; Borisov et al., 2011) functioning as quinol oxidases.

Type A oxidases encoded by the cox gene cluster are present in a wide range of bacteria and they have a high proton-pumping activity (Brzezinski et al., 2004; Arai et al., 2014). In general, aa3 type oxidases show a low affinity for oxygen and usually play a dominant role under high-oxygen conditions in bacteria such as R. sphaeroides and B. subtilis (Gabel and Maier, 1993; Winstedt and von Wachenfeldt, 2000; Arai et al., 2008). If we extend these widely accepted biochemical concepts to P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707 redox chain the peculiarity of the membrane terminal oxidase content of this BCPs degrader becomes apparent. In fact, while the sequence analysis allowed classifying Cox in the type A subfamily, the presence in the predicted subunit II (CoxM) of an uncommon extra C-terminal domain carrying two c-type hemes binding consensus sequences, suggests that this protein is a ccaa3 type HCO. In agreement to this the C-terminal extension of subunit II (CoxB) from the facultative anaerobic proteobacterium S. oneidensis MR-1 was shown to bind two c type hemes (Le Laz et al., 2014). Similarly, this unusual feature was reported in Desulfovibrio spp. (Lobo et al., 2008) and some species of the genus Psychromonas, Colwellia, and Methylosarcina (Le Laz et al., 2014). In Shewanella MR-1, the Ccaa3 oxidase was expressed at a low level but only under O2-rich growth conditions in LB-medium (Le Laz et al., 2014) while in KF707 the Ccaa3 oxidase is always expressed at a low level regardless the cell growth phase (Figure 2).

As opposed to the CoxM subunit, the CoxB subunit II of T. thermophilus, B.subtilis, and R. marinus has an extra domain carrying only one c-type heme (Lauraeus et al., 1991; Mather et al., 1991). This is the case of caa3 type oxidase of KF707 which is highly expressed during the stationary phase in biphenyl (Figure 2). In KF707, the presence of c-type hemes in the oxidase catalytic subunits is not only predicted by the amino acid sequences (Supplementary Material—Alignment 1) but it was supported by spectroscopic analysis in which a decrease of the c-type heme content in membranes from KFΔcox1-2 mutant (Caa3/Ccaa3 minus) is seen (Figure S3; Table 2).

Oxidases of cbb3 type normally show a very high affinity for oxygen and low proton-translocation efficiency. In bacteria such as P. denitrificans, R. sphaeroides, and R. capsulatus, cbb3 oxidases are known to be induced under low oxygen conditions (Preisig et al., 1996a; Mouncey and Kaplan, 1998; Swem and Bauer, 2002). In P. aeruginosa PAO1 one of these cbb3 type oxidases, Cbb31, is constitutively expressed and plays a primary role in aerobic growth irrespective of oxygen concentration; on the contrary, the expression of Cbb32 varies under low oxygen conditions or at the stationary growth phase (Kawakami et al., 2010). The latter regulatory mechanism is also present in KF707 grown on glucose or biphenyl as clearly demonstrated by the constitutive expression of Cbb31 while the Cbb32 expression varies as a function of the carbon source and growth phase being repressed in the stationary phase of growth in biphenyl (Figure 2).

CIO oxidases are copper-free enzymes that are insensitive to millimolar concentration of cyanide and they function as quinol:oxygen oxidoreductases. Direct determination through the use of Q-electrodes of the Q-pool redox state in membranes from aerobically grown R. capsulatus endowed with Cbb3 and CIO oxidases, indicated that the quinol oxidase of CIO type starts being involved in respiration when the Q-pool reduction level reaches ~25% (Zannoni and Moore, 1990). If this observation is applied to analogous bacterial respiratory chains as those of R. sphaeroides, P. aeruginosa and KF707 it is apparent that CIO pathways operate as redox valves to prevent the Q-pool from exceeding the 25–50% oxidation-reduction level that is the optimum Q-pool redox state to warrant an efficient energy transduction by the respiratory chain (Klamt et al., 2008). This would explain why cytochrome Cbb3 oxidases are prone to sense environmental redox changes and this is why cioABC genes coding for CIO, are up-regulated by deletion of the constitutive Cbb31 oxidase in P. aeruginosa (Comolli and Donohue, 2004). Interestingly, also in P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707 the CIO promoter is up-regulated by deletion of the Cbb31 isoform (this work Figure S5) as also confirmed by respiratory activities measured in membranes from Cbb31 minus cells (KFΔcco1 mutant) in which the CIO pathway catalyzes 60% of respiration as compared to only 17% of W.T. cells (Table 3). This result confirms that CIO has a minor role in KF707 respiration unless the Cbb31 isoform is lacking.

The cyt bc1 complex and soluble c-type cytochromes

As shown in the past (Di Tomaso et al., 2002), both NADH- and succinic-dehydrogenases channel their electrons into a quinol/cytochrome c oxido-reductase complex (also referred to as complex III or cyt bc1 complex) which contains b- and c-type heme subunits coded by 1,212 and 780 bp genes, respectively (BAU72674; BAU72675) while the ORF coding for the Rieske domain iron sulfur, [2Fe-S] reductase subunit of the bc1 complex, is coded by 591 bp gene (BAU72673). The latter genome annotation confirms early data indicating that the NADH-dependent respiration in KF707 is inhibited by the antibiotic antimycin A which is a specific inhibitor of the cyt bc1 complex at the heme bH-Qi interaction site level (Cramer and Knaff, 1990; Di Tomaso et al., 2002).

Analysis of KF707 annotated genome indicated the presence of genes encoding for soluble c-type cytochromes, namely: three genes identified as cyt c4 (BAU71765, BAU75530, and BAU75507) and two genes identified as cyt c5 (BAU77240 and BAU71764) (Supplementary Material—Table S3). Genes BAU71765 and BAU71764 coding for c4 and c5, respectively, are located in tandem on the same operon (not shown). In the working scheme of Figure 4 (see below) these two soluble c-type cytochromes, collectively named as Cyt cs, are supposed to function as electron donors to KF707 terminal oxidases. Because the aim of the present study was to analyse the role of the respiratory oxidases no further effort was made to understand the specific function of the soluble c-type hemes in KF707.

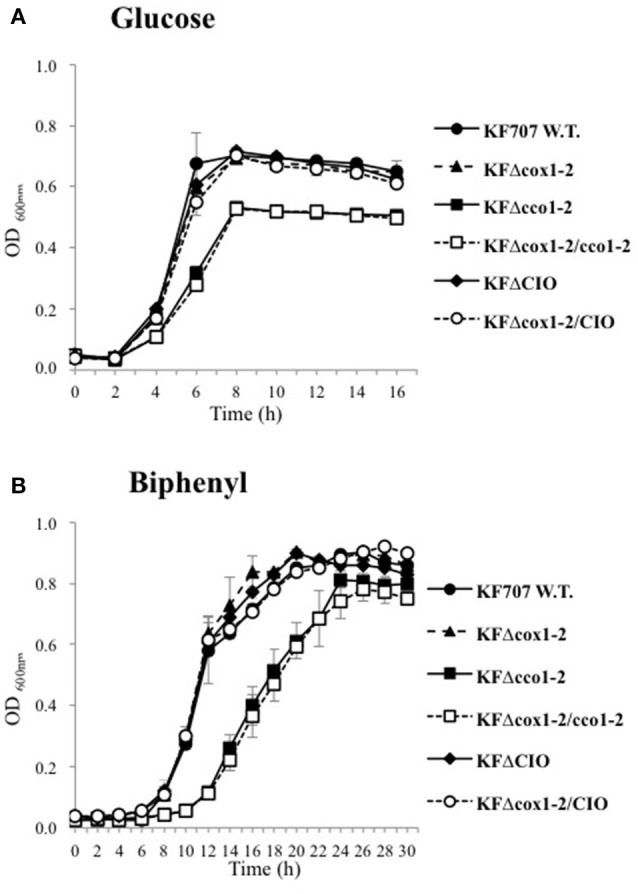

Figure 4.

Block scheme illustrating the putative chain of KF707 based on spectroscopic, functional, and genetic analysis (this work and Di Tomaso et al., 2002). Symbols used: Succ, succinate dehydrogenase; NADH, NADH dehydrogenase; Cyt Cs, soluble cytochrome(s) c; bc1 complex, cytochrome bc1 complex III; CIO, cyanide insensitive oxidase (bd type) (encoded by cioABC); caa3, cytochrome c oxidase (encoded by coxI-II-III cluster); ccaa3, cytochrome c oxidase (encoded by coxMNOP); cbb31, cytochrome c oxidase (encoded by ccoN1O1Q1P1); cbb32, cytochrome c oxidase (encoded by ccoN2O2Q2P2); KFΔcco1, Cbb31 minus mutant. The size and color of the arrows symbolize the % level of expression of terminal oxidases under the tested growth conditions, namely: cells grown in glucose or biphenyl and harvested during their exponential (Expo) or stationary (Stat) phase of growth. The actual expression values are those of Figure 2.

Effect of the carbon source on the arrangement of KF707 respiratory chain

KF707 cells grown in LB-medium do not contain detectable amounts of aa3-type hemes regardless the phase of growth (Di Tomaso et al., 2002). Conversely we show here that spectroscopic significant amounts of c(c)aa3 type hemes are present in KF707 cells grown in minimal-salt media supplemented with biphenyl as sole carbon source (Table 2). Further, results of Figure 2 and Table 4 indicate that both cox123 gene expression and catalytic activity (Caa3 oxidase) are greatly enhanced in biphenyl grown cells. This effect was paralleled by a drastic decrease (7-fold) in the expression of the Cbb32 oxidase which was not compensated by a parallel increase of the CIO quinol oxidase activity while the Cbb31 oxidase was constitutively expressed (Figure 2 and Table 4). These results are of particular interest because they outline a new bioenergetics scenario in which two respiratory oxidases of P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707 are modulated by biphenyl that is the metabolite which allows the co-metabolic degradation of PCBs by KF707. In this respect, while the response of the central carbon catabolism to environmental signals such as oxygen and/or nutritional compounds has been analyzed in some detail (Arras et al., 1998; Krooneman et al., 1998), the modulation of the oxidative ETC by the carbon source used for growth is far less documented (Dominguez-Cuevas et al., 2006; Arai, 2011; Arai et al., 2014). It is known that oxidases of aa3 type are affected by carbon starvation which was shown to induce a cox gene up-regulation in P. aeruginosa. This regulatory mechanism is linked to a cell response toward a more efficient energy-transducing aa3 oxidase under low nutrient conditions (Kawakami et al., 2010; Arai, 2011). As far as concern the role of c(c)aa3 type oxidases in KF707 grown in biphenyl, the growth results can be summarized as following (Figure 3B): (1) the growth rate of the c(c)aa3 double mutant (g = 94 ± 6.1 min) is similar to that of W.T. (g = 97 ± 8.5 min); (2) the lack of both Cbb31 and Cbb32 oxidases slows down KF707 cell growth (g = 140 ± 21 min); (3) the C(c)aa3/CIO minus phenotype is only slightly affected in its growth rate (g = 117 ± 1.5 min) as compared to W.T.; (4) the Cbb31 minus phenotype is impaired in its growth rate (g = 151 ± 1.7 min) in spite of Caa3 over-expression; (5) growth of the quadruple cytochrome oxidase mutant Cbb31-2/C(c)aa3, although impaired, is still supported by the oxidase activity of CIO which is up-regulated (g = 146 ± 16 min), and finally (6) all attempts to obtain a KF707 mutant carrying a Cbb31-2/CIO minus phenotype were unsuccessful. Overall these data suggest that the C(c)aa3 oxidases of KF707 are unable to sustain aerobic growth when they are present as the only terminal oxidases as it was noticed in Shewanella MR-1 whose genome is predicted to encode for a terminal Cox oxidase annotated as Ccaa3 oxidase (Le Laz et al., 2014). In the past it was shown that a mutant of P. aeruginosa PAO1 that lacked four terminal oxidase gene clusters except for the cox genes (strain QXAa) was unable to grow aerobically in LB (Arai et al., 2014). More recently, a suppressor mutant of QXAa (QXAaS2) that grew aerobically using only the cox genes for caa3 (formerly reported as aa3) was described, in which a mutation in the two-component regulator RoxSR was necessary for the aerobic growth of PAO1 in LB (Osamura et al., 2017). Apparently, the expression and function of bacterial cyt c oxidases of C(c)aa3 type under variable growth conditions is far from being fully examined (Brzezinski et al., 2004; Arai, 2011; Osamura et al., 2017).

The scheme in Figure 4 represents the state of knowledge on the functional arrangement of the ETC in the PCBs-degrader P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707. A study is currently underway to understand the ETC's regulation mechanism as a function of the two carbon sources here used for cell growth, glucose, and biphenyl, along with the search for growth conditions under which the Ccaa3 oxidases of KF707 is significantly expressed.

Author contributions

SF and FS: conceived, designed, and performed part of the experiments, assisted in design of the study and co-wrote the Manuscritpt. MC: assisted in design of the study and co-wrote the manuscript. FC and RT assisted in design of the study. DZ: conceived, directed, supervised, and co-wrote the Manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the University of Bologna for supporting this work (RFO grants 2013-16) and the “Vasco e GC Rossi Foundation” (Microbial Biofilm grant 2012-2015). FS was supported by a PhD fellowship given by the University of Bologna. The contribution of RT was supported by NSERC grant (RGPIN/219895-2010). We are also indebted to Tania Triscari-Barberi, Roberta Rosa Susca, Domenico Simone, Marcella Attimonelli for their early contribution in the annotation and sequencing of P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707 genome (Triscari-Barberi et al., 2012).

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01223/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abramowicz D. A. (1990). Aerobic and anaerobic biodegradation of PCBs: a review. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 10, 241–251. 10.3109/07388559009038210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Ortega C., Harwood C. S. (2007). Responses of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to low oxygen indicate that growth in the cystic fibrosis lung is by aerobic respiration. Mol. Microbiol. 65, 153–165. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05772.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai H. (2011). Regulation and function of versatile aerobic and anaerobic respiratory metabolism in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 2:103. 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai H., Kawakami T., Osamura T., Hirai T., Sakai Y., Ishii M. (2014). Enzymatic characterization and in vivo function of five terminal oxidases in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 196, 4206–4215. 10.1128/JB.02176-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai H., Roh J. H., Kaplan S. (2008). Transcriptome dynamics during the transition from anaerobic photosynthesis to aerobic respiration in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. J. Bacteriol. 190, 286–299. 10.1128/JB.01375-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arras T., Schirawski J., Unden G. (1998). Availability of O2 as a substrate in the cytoplasm of bacteria under aerobic and microaerobic conditions. J. Bacteriol. 180, 2133–2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borisov V. B., Gennis R. B., Hemp J., Verkhosky M. I. (2011). The cytochrome bd respiratory oxygen reductases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1807, 1398–1413. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bott M., Preisig O., Hennecke H. (1992). Genes for a second terminal oxidase in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Arch. Microbiol. 158, 335–343. 10.1007/BF00245362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer H. W., Roulland-Dussoix D. (1969). A complementation analysis of the restriction and modification of DNA in Escherichia coli. 41, 459–472. 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90288-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzezinski P., Larsson G., Adelroth P. (2004). Functional aspects of heme-copper terminal oxidases, in Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration, Vol. 15: Respiration in Archaea and Bacteria. Diversity of Prokaryotic Electron Transport Carriers, ed Zannoni D. (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; ), 129–153. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno E., Mesa S., Bedmar E. J., Richardson D., Delgado M. J. (2012). Bacterial adaptation of respiration from oxic to microoxic and anoxic conditions: redox control. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 16, 819–852. 10.1089/ars.2011.4051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H.-Y., Ahn Y., Pace L. A., Lin M. T., Lin Y.-H., Gennis R. B. (2010). The diheme cytochrome c4 from Vibrio cholerae is a natural electron donor to the respiratory cbb3 oxygen reductase. Biochemistry 49, 7494–7503. 10.1021/bi1004574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K. H., Gaynor J. B., White K. G., Lopez C., Bosio C. M., Karkhoff-Schweizer R. R., et al. (2005). A Tn7-based broad-range bacterial cloning and expression system. Nat. Methods 6, 443–448. 10.1038/nmeth765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K. H., Schweizer H. P. (2006). mini-Tn7 insertion in bacteria with single attTn7 sites: example Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nat. Protoc. 1, 153–161. 10.1038/nprot.2006.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comolli J. C., Donohue T. J. (2002). Pseudomonas aeruginosa RoxR, a response regulator related to Rhodobacter sphaeroides PrrA, activates the expression of the cyanide-insensitive terminal oxidase. Mol. Microbiol. 45, 755–768. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03046.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comolli J. C., Donohue T. J. (2004). Differences in two Pseudomonas aeruginosa cbb3 cytochrome oxidases. Mol. Microbiol. 51, 1193–1203. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03904.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer W. A., Knaff D. B. (1990). Energy Transduction in Biological Membranes. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham L., Pitt M., Williams H. D. (1997). The cioAB genes from Pseudomonas aeruginosa code for a novel CN− insensitive terminal oxidase related to the cytochrome bd quinol oxidases. Mol. Microbiol. 24, 579–591. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3561728.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'mello R., Hill S., Poole R. K. (1996). The cytochrome bd quinol oxidase in Escherichia coli has an extremely high oxygen affinity and two-oxygen binding haems: implications for regulation of activity in vivo by oxygen inhibition. Microbiology 142, 755–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daldal F., Mandaci S., Winterstein C., Myllykallio H., Duyck K., Zannoni D. (2001). Mobile cytochrome c2 and membrane-anchored cytochrome cy are both efficient electron donors to the cbb3- and aa3-type cytochrome c oxidases during respiratory growth of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 183, 2013–2024. 10.1128/JB.183.6.2013-2024.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Tomaso G., Fedi S., Carnevali M., Manegatti M., Taddei C., Zannoni D. (2002). The membrane-bound respiratory chain of Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707 cells grown in the presence or absence of potassium tellurite. Microbiology 148, 1699–1708. 10.1099/00221287-148-6-1699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Cuevas P., Gonzales-Pastor J. E., Marques S., Ramos J. L., de Lorenzo V. (2006). Transcriptional tredoff between metabolic and stress-response programs in Pseudomonas putida KT2440 cells exposed to toluene. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 11981–11991. 10.1074/jbc.M509848200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedi S., Carnevali M., Fava F., Andracchio A., Zappoli S., Zannoni D. (2001). Polychlorinated biphenyl degradation activities and hybridization analyses of fifteen aerobic strains isolated from a PCB-contaminated site. Res. Microbiol. 152, 583–592. 10.1016/S0923-2508(01)01233-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figurski D. H., Helinski D. R. (1979). Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 76, 1648–1652. 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujihara H., Yoshida H., Matsunaga T., Goto M., Furukawa K. (2006). Cross-regulation of biphenyl- and salicylate-catabolic genes by two regulatory systems in Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707. J. Bacteriol. 188, 4690–4697. 10.1128/JB.00329-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa K., Hirose J., Suyama A., Zaiki T., Hayashida S. (1993). Gene components responsible for discrete substrate specificity in the metabolism of biphenyl (bph) and toluene (tod) operons. J. Bacteriol. 175, 5224–5232. 10.1128/jb.175.16.5224-5232.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa K., Miyazaki T. (1986). Cloning of a gene cluster encoding biphenyl and chlorobiphenyl degradation in Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707. J. Bacteriol. 166, 392–398. 10.1128/jb.166.2.392-398.1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabel C., Maier R. J. (1993). Oxygen-dependent transcriptional regulation of cytochrome aa3 in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J. Bacteriol. 175, 128–132. 10.1128/jb.175.1.128-132.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D. (1983). Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166, 557–580. 10.1016/S0022-2836(83)80284-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang T. T., Karkhoff-Schweizer R. R., Kutchma A. J., Schweizer H. P. (1998). A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene 212, 77–86. 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00130-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi K., Aramaki M., Kimura T., Naito Y., Udaka T., Uchikawa M., et al. (2007). Identification of a prosencephalic-specific enhancer of SALL1: comparative genomic approach using the chick embryo. Pediatr. Res. 61, 660–665. 10.1203/pdr.0b013e318053423a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jünemann S. (1997). Cytochrome bd terminal oxidase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1321, 107–127. 10.1016/S0005-2728(97)00046-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami T., Kuroki M., Ishii M., Igarashi Y., Arai H. (2010). Differential expression of multiple terminal oxidases for aerobic respiration in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ. Microbiol. 12, 1399–1412. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02109.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishikawa J.-I., Kabashima Y., Kurokawa T., Sakamato J. (2010). The cytochrome bcc-aa3 type respiratory chain of Rhodococcus rhodochrous. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 110, 42–47. 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2009.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klamt S., Grammel H., Starube R., Ghosh R., Gilles E. D. (2008). Modelling the electron transport chain of purple non-sulfur bacteria. Mol. Syst. Biol. 4:156 10.1038/msb4100191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch H. G., Winterstein C., Saribas A. S., Alben J. O., Daldal F. (2000). Roles of the ccoGHIS gene products in the biogenesis of the cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase. J. Mol. Biol. 297, 49–65. 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krooneman J., Moore E. R. B., van Velzen J. C. L., Prins R. A., Forney L. J., Gottschal J. C. (1998). Competition for oxygen and 3-chlorobenzoate between two aerobic bacteria using different degradation pathways. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 26, 171–179. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.1998.tb00503.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lauraeus M., Haltia T., Saraste M., Wikstrom M. (1991). Bacillus subtilis expresses two kinds of haem-A-containing terminal oxidases. Eur. J. Biochem. 197, 699–705. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb15961.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Laz S., Kpebe A., Bauzan M., Lignon S., Rousset M., Brugna M. (2014). A biochemical approach to study the role of the terminal oxidases in aerobic respiration of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. PLoS ONE 9:e86343. 10.1371/journal.pone.0086343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo S. A., Almeida C. C., Carita J. N., Teixeira M., Saraiva L. M. (2008). The haem-copper oxygen reductase of Desulfovibrio vulgaris contains a dihaem cytochrome c in subunit II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1777, 1528–1534. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry O. H., Rosebrough N. J., Farr A. L., Randall R. J. (1951). Protein measurement with Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193, 265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons J. A., Aragao D., Slattery O., Pisliakov A. V., Soulimane T., Caffrey M. (2012). Structural insights into electron transfer in caa3-type cytochrome oxidase. Nature 487, 514–520. 10.1038/nature11182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrs B. L., Gest H. (1973). Genetic mutations affecting the respiratory electron transport system of the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodopseudomonas capsulate. J. Bacteriol. 114, 1045–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maseda H., Sawada I., Saito K., Uchiyama H., Nakae T., Nomura N. (2004). Enhancement of the mexAB-oprM efflux pump expression by a quorum-sensing autoinducer and its cancellation by a regulator, MexT, of the mexEF-oprN efflux pump operon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemiother. 48, 1320–1328. 10.1128/AAC.48.4.1320-1328.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M. W., Springer P., Fee J. A. (1991). Cytochrome oxidase genes from Thermus thermophilus. Nucleotide sequence and analysis of the deduced primary structure of subunit IIc of cyt caa3. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 5025–5035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita K., Yamada M., Shinagawa E., Adachi O., Ameyama M. (1983). Membrane-bound respiratory chain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa grown aerobically. A KCN-insensitive alternate oxidase chain and its energetics. J. Biochem. 93, 1137–1144. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a134239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouncey N. J., Kaplan S. (1998). Oxygen regulation of the ccoN gene encoding a component of the cbb3 oxidase of Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1.T: involvement of the FnrL protein. J. Bacteriol. 180, 2228–2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikel P. I., Chavarria M. (2015). Quantitative physiology approaches to understand and optimize reducing power availability in environmental bacteria, in Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology Protocols, eds McGenity T. J., Timmis K. N., Nogales-Fernandez B. (Heidelberg: Humana Press; ), 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Nikel P. I., Perez-Pantoja D., de Lorenzo V. (2016). Pyridine nucleotide transhydrogenases enable redox balance of Pseudomonas putida during biodegradation of aromatic compounds. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 3565–3582. 10.1111/1462-2920.13434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osamura T., Kawakami T., Kido R., Ishii M., Arai K. (2017). Specific expression and function of the A-type cytochrome oxidase under starvation conditions in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS ONE 12:e0177957. 10.1371/journal.pone.0177957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitcher R. S., Watmough N. J. (2004). The Bacterial cytochrome cbb3 oxidases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1655, 388–399. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2003.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole R. K., Cook G. M. (2000). Redundancy of aerobic respiratory chains in bacteria? Routes, reasons and regulation. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 43, 165–224. 10.1016/S0065-2911(00)43005-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preisig O., Zufferey R., Hennecke H. (1996a). The Bradyrhizobium japonicum fixGHIS genes are required for the formation of the high-affinity cbb3-type cytochrome oxidase. Arch. Microbiol. 165, 297–305. 10.1007/s002030050330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preisig O., Zufferey R., Thöny-Meyer L., Appleby C. A., Hennecke H. (1996b). A high-affinity cbb3-type cytochrome oxidase terminates the symbiosis-specific respiratory chain of Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J. Bacteriol. 178, 1532–1538. 10.1128/jb.178.6.1532-1538.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojo F. (2010). Carbon catabolite repression in Pseudomonas: optimizing metabolic versatility and interactions with the environment. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34, 658–684. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00218.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook K., Fritsch E. F., Maniatis T. (1989). Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd Edn. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. [Google Scholar]

- Sevilla E., Alvarez-Ortega C., Krell T., Rojo F. (2013). The Pseudomonas putida HskA hybrid sensor kinase responds to redox singals and contributes to the adaptation of the electron transport composition in response to oxygen availability. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 5, 825–834. 10.1111/1758-2229.12083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu K. (2014). Regulation systems of bacteria such as E. coli in response to nutrient limitation and environmental stresses. Metabolites 4, 1–35. 10.3390/metabo4010001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siletsky S. A., Rapport F., Poole R. K., Borisov V. B. (2016). Evidence for fast electron transfer between the high-spin haems in cytochrome bd-I from Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE 11:e0155186. 10.1371/journal.pone.0155186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa F. L., Alves R. J., Ribeiro M. A., Pereira-Leal J. B., Teixeira M., Pereira M. M. (2012). The superfamily of heme-copper oxygen reductases: types and evolutionary considerations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 629–637. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover C. K., Pham X. Q., Erwin A. L., Mizoguchi S. D., Warrener P., Hickey M. J., et al. (2000). Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406, 959–964. 10.1038/35023079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swem D. L., Bauer C. E. (2002). Coordination of ubiquinol oxidase and cytochrome cbb3 oxidase expression by multiple regulators in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Bacteriol. 184, 2815–2820. 10.1128/JB.184.10.2815-2820.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taira K., Hirose J., Hayashida S., Furukawa K. (1992). Analysis of bph operon from the polychlorinated biphenyl-degrading strain of Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 4844–4853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J. (1994). CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680. 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremaroli V., Fedi S., Tamburini S., Viti C., Tatti E., Ceri H., et al. (2011). A histidine-kinase cheA gene of Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligens KF707 not only has a key role in chemotaxis but also affects biofilm formation and cell metabolism. Biofouling 27, 33–46. 10.1080/08927014.2010.537099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremaroli V., Fedi S., Turner R. J., Ceri H., Zannoni D. (2008). Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707 upon biofilm formation on a polystyrene surface acquire a strong antibiotic resistance with minor changes in their tolerance to metal cations and metalloid oxyanions. Arch. Microbiol. 190, 29–39. 10.1007/s00203-008-0360-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremaroli V., Fedi S., Zannoni D. (2007). Evidence for a tellurite dependent generation of reactive oxygen species and absence of a tellurite mediated adaptive response to oxidative stress in cells of Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707. Arch. Microbiol. 187, 127–135. 10.1007/s00203-006-0179-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremaroli V., Vacchi-Suzzi C., Fedi S., Ceri H., Zannoni D., Turner R. J. (2010). Tolerance of Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707 to metals, polychlorobiphenyls and chlorobenzoates: effects on chemotaxis-, biofilm- and planktonic-grown cells. FEMS. Microbiol. Ecol. 74, 291–301. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.00965.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triscari-Barberi T., Simone D., Calabrese F. M., Attimonelli M., Hahn K. R., Amoako K. K., et al. (2012). Genome sequence of the polychlorinated-biphenyl degrader Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707. J. Bacteriol. 194, 4426–4427. 10.1128/JB.00722-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstedt L., von Wachenfeldt C. (2000). Terminal oxidases of Bacillus subtilis strain 168: one quinol oxidase, cytochrome aa3 or cytochrome bd, is required for aerobic growth. J. Bacteriol. 182, 6557–6564. 10.1128/JB.182.23.6557-6564.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zannoni D., Moore A. L. (1990). Measurement of the redox state of the ubiquinone pool in Rhodobacter capsulatus membrane fragments. FEBS Lett. 271, 123–127. 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80387-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.