Abstract

Thirteen Neisseria meningitidis clinical isolates from Africa, Asia, and the United States for which the tetracycline MICs were elevated (≥8 μg/ml) were examined for 14 recognized resistance genes. Only the drug efflux mechanism encoded by tet(B) was detected. All isolates were in serogroup A, belonged to complex ST-5, and were closely related by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis analysis.

Neisseria meningitidis is a leading cause of bacterial meningitis and severe sepsis in the United States, in other industrialized countries of the Americas and Europe, and in developing parts of the world (16). It is also a major cause of periodic epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa and areas of the Middle East (16). Patients with invasive meningococcal infection must be treated with effective antibiotics because of the severity of meningococcemia and meningitis, and close contacts should receive prophylactic treatment to prevent possible secondary cases. Penicillin has historically been the most effective antibiotic for therapy, but strains with reduced susceptibility to penicillin have been reported in Europe, South America, Asia, Australia, and the United States (3, 7, 14, 17, 18, 20). Resistance to antimicrobial agents that may be used for prophylaxis of case contacts, including resistance to sulfonamides, rifampin, and tetracycline, has been reported in several countries (4, 5, 16, 17).

A group of 441 N. meningitidis clinical isolates from 15 countries and 20 U.S. states recovered between 1917 and 2004 has been studied in order to develop susceptibility testing breakpoints for this species with a number of drugs, including tetracycline, minocycline, and doxycycline (with a subset of 124 isolates). MICs were determined by the NCCLS broth microdilution procedure with lysed horse blood-supplemented Mueller-Hinton broth incubated for 20 to 24 h at 35°C in 5% CO2 (10). Streptococcus pneumoniae ATCC 49619 and Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 were used for quality control of the medium and antibiotics (11). Elevated tetracycline MICs (≥8 μg/ml) were noted for some strains, while most of the strains were inhibited by 2 μg/ml or less (modal value of 0.5 μg/ml) (Table 1). The mechanism responsible for the elevated tetracycline MICs was investigated in this study by PCR for the responsible genes with previously described primers for the tet(A), tet(B), tet(C), tet(D), tet(E), tet(G), tet(K), tet(L), tet(M), tet(O), tet (Q), tetA(P), tet(W), and tet(X) genes (1, 12, 13, 15). Universal primers RW01 and DG74, used to detect ribosomal DNA, were used to demonstrate adequate template DNA for amplification (8).

TABLE 1.

Frequencies of MICs for 441 isolates of N. meningitidis and the presence or absence of tet(B)

| MIC (μg/ml) | Tetracycline (n = 441)

|

Minocycline (n = 441)

|

Doxycycline (n = 124)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of MIC | tet(B) | Frequency of MIC | tet(B) | Frequency of MIC | tet(B) | |

| 0.06 | 10 | NAa | ||||

| 0.12 | 4 | NA | 230 | 2/4b | 3 | NA |

| 0.25 | 89 | NA | 165 | 11/20 | 25 | 0/1 |

| 0.5 | 260 | 0/1 | 36 | 0/11 | 60 | 0/6 |

| 1 | 57 | 0/10 | 33 | 11/26 | ||

| 2 | 18 | 0/11 | 3 | 3/3 | ||

| 4 | 0 | |||||

| 8 | 7 | 7/7 | ||||

| 16 | 6 | 6/6 | ||||

NA, not available.

Number of isolates with tet(B)/total.

All 13 isolates for which the tetracycline MIC was 8 or 16 μg/ml produced a 664-bp PCR product consistent with tet(B) with the primers described by Ng et al. (12) and a 574-bp product with the primers suggested by Roe et al. (15). None of the strains examined for which the MIC was 1 or 2 μg/ml produced a PCR product with either set of primers. The presence or absence of tet(B), on the basis of the tetracycline MIC, is depicted in Table 1. A representative PCR product from each primer set was sequenced by the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio Nucleic Acids Core Facility with Big Dye Terminator v3.1 chemistry (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, Calif.) and 3100 capillary sequencers (Applied Biosystems, Inc.) and shown to contain >99% homology with tet(B) from E. coli when matched with sequences identified as tet(B) in the GenBank database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) (2). However, unlike E. coli strains possessing tet(B), the meningococcal strains in this study were uniformly susceptible to minocycline (MIC ≤ 0.25 μg/ml) and the doxycycline MICs for them were slightly elevated (Table 1) (9).

DNA extracts from all 13 resistant meningococcal isolates were examined by multiple methods in an attempt to detect plasmids as the possible location of the tet(B) sequences. While these experiments did not reveal the presence of plasmids, it is not possible to say with certainly that the tet(B) sequences reside in the chromosome. However, Takahashi et al. (H. Takahashi, H. Watanabe, T. Kuroki, Y. Watanabe, and S. Yamai, Letter, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:4045-4046, 2002) found tet(B) to be chromosomally mediated in a single meningococcal isolate colonizing a patient in Japan. Additional experiments are under way to definitively characterize the location of the gene in our isolates.

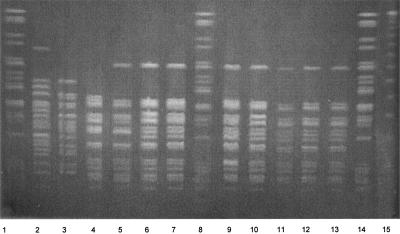

All 13 tetracycline-resistant isolates belonged to serogroup A, clonal complex ST-5 (Deborah Talkington, personal communication), and were recovered from patients in five countries and four U.S. states between 1999 and 2002 (Table 2). Seven strains were previously determined to be in multilocus enzyme electrophoresis subgroup III (Talkington, personal communication), and all 13 isolates were either identical or closely related by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE); i.e., they differed by no more than three bands (Fig. 1) (19). All 13 isolates were also resistant to sulfisoxazole and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole but were susceptible to penicillin, other relevant beta-lactams, and rifampin (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Information about 13 tetracycline-resistant clinical isolates of N. meningitidis

| Isolate | Date isolated | Location | Serogroup | ETa | 16Sb | PFGE pattern | Tetracycline MIC (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NM266 | 03/10/2000 | New York | A | III | 5 | CRc | 8 |

| NM267 | 05/19/2000 | Michigan | A | NA | 5 | CR | 8 |

| NM268 | 06/25/2000 | Colorado | A | NA | 5 | CR | 8 |

| NM269 | 12/03/2000 | New York | A | NA | 5 | CR | 16 |

| NM270 | 02/17/2001 | Pennsylvania | A | NA | 5 | CR | 16 |

| NM271 | 08/02/2001 | Dhaka | A | NA | 5 | CR | 16 |

| NM272 | 06/02/2002 | Dhaka | A | NA | 5 | CR | 16 |

| NM436 | 12/19/2000 | Sudan | A | III | 5 | Id | 8 |

| NM437 | 12/19/2000 | Sudan | A | III | 5 | I | 16 |

| NM438 | 11/25/1999 | Cameroon | A | III | 5 | I | 8 |

| NM439 | 05/30/2000 | Niger | A | III | 5 | I | 8 |

| NM440 | 05/30/2000 | Niger | A | III | 5 | I | 16 |

| NM441 | 10/13/1999 | Chad | A | III | 5 | I | 8 |

ET enzyme (multilocus enzyme electrophoresis) type.

16S rRNA sequence type.

CR, closely related.

I, indistinguishable.

FIG. 1.

PFGE profiles of genomic DNAs from clinical isolates of N. meningitidis after digestion with SpeI. Reference strain (Pseudomonas aeruginosa) DNA digests are in lanes 1, 8, and 14. Lanes 2 and 3 contain tetracycline-susceptible isolates NM257 and NM259, respectively. The remaining lanes contain tetracycline-resistant isolates NM269 (lane 4), NM267 (lane 5), NM268 (lane 6), NM277 (lane7), NM271 (lane 9), NM437 (lane10), NM438 (lane 11), NM439 (lane 12), and NM441 (lane 13). Lane 15 contains the lambda ladder DNA size standard.

Tetracycline resistance in this collection of meningococcal isolates from multiple continents was associated with the drug efflux mechanism encoded by tet(B). The presence of tet(B) was reported previously in a single strain (Takahashi et al., Letter). However, an earlier report indicated the presence of the ribosomal protection mechanism encoded by tet(M) in some meningococci (6). In the meningococcal isolates in this study, the tet(B) mechanism did not lead to elevated minocycline MICs. Possible shortcomings of this study include the fact that these strains were not collected consecutively or all derived from population-based surveillance studies. Thus, it is not possible to define the frequency of tetracycline resistance overall or even among all serogroup A isolates. Furthermore, we cannot determine when tetracycline resistance due to tet(B) first arose in meningococci or why it appears to be restricted to only one meningococcal serogroup. The isolate reported previously to contain tet(B) belonged to serogroup B (H. Takahashi, personal communication). Lastly, it is not clear why the efflux protein encoded by tet(B) in meningococci does not appear to be able to remove minocycline from the bacterial cells, as has been the case with tet(B)-mediated resistance in other organisms (e.g., E. coli) (9). However, this suggests that minocycline may continue to represent one option for prophylaxis of invasive meningococcal case contacts, even in those strains that contain the tet(B) determinant.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant RS1/CCR622402 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

We thank Tanja Popovic, Deborah Talkington, and Fred Tenover for kindly providing many of the isolates described in this study. We thank Sophia Pina and Brian Wickes for advice on molecular assays and Cynthia Kelly for performing the PFGE testing of the isolates.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aminov, R. I., N. Garrigues-Jeanjean, and R. I. Mackie. 2001. Molecular ecology of tetracycline resistance: development and validation of primers for detection of tetracycline resistance genes encoding ribosomal protection proteins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:22-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benson, D. A., I. Karsch-Mizrachi, D. J. Lipman, J. Ostell, and D. L. Wheeler. 2004. GenBank: update. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:D23-D26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunen, A., W. Peetermans, J. Verhaegen, and W. Robberecht. 1993. Meningitis due to Neisseria meningitidis with intermediate susceptibility to penicillin. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 12:969-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galimand, M., G. Gerbaud, M. Guibourdenche, J.-Y. Riou, and P. Courvalin. 1998. High-level chloramphenicol resistance in Neisseria meningitidis. N. Engl. J. Med. 339:868-918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galløe, A. M., L. B. Madsen, N. Graudal, and J. P. Kampmann. 1993. Rifampicin-resistant meningococci causing invasive disease and failure of chemoprophylaxis. Lancet 341:1152-1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knapp, J. S., S. R. Johnson, J. M. Zinilman, M. C. Roberts, and S. A. Morse. 1988. High-level tetracycline resistance resulting from TetM in strains of Neisseria species, Kingella denitrificans, and Eikenella corrodens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 32:765-767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Latorre, C., A. Gené, T. Juncosa, C. Muñoz, and A. González-Cuevas. 2000. Neisseria meningitidis: evolution of penicillin resistance and phenotype in a children's hospital in Barcelona, Spain. Acta Pædiatr. 89:661-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leong, D. U., and K. S. Greisen. 1993. PCR detection of bacteria found in cerebrospinal fluid, p. 300-306. In D. H. Pershing, T. F. Smith, F. C. Tenover, and T. J. White (ed.), Diagnostic molecular microbiology: principles and applications. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 9.Mendez, B., C. Tachibana, and S. B. Levy. 1980. Heterogeneity of tetracycline resistance determinants. Plasmid 3:99-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2003. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A6. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 11. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2004. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Supplement M100-S14. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 12.Ng, L.-K., I. Martin, M. Alfa, and M. Mulvey. 2001. Multiplex PCR for the detection of tetracycline resistant genes. Mol. Cell. Probes 15:209-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsvik, B., I. Olsen, and F. C. Tenover. 1995. Detection of tet(M) and tet(O) using the polymerase chain reaction in bacteria isolated from patients with periodontal disease. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 10:87-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richter, S. S., K. A. Gordon, P. R. Rhomberg, M. A. Pfaller, and R. N. Jones. 2001. Neisseria meningitidis with decreased susceptibility to penicillin: report from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program, North America, 1998-99. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 41:83-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roe, D. E., P. H. Braham, A. Weinberg, and M. C. Roberts. 1995. Characterization of tetracycline resistance in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 10:227-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenstein, N. E., B. A. Perkins, D. S. Stephens, T. Popovic, and J. M. Hughes. 2001. Meningococcal disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 344:1378-1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenstein, N. E., S. A. Stocker, T. Popovic, F. C. Tenover, and B. A. Perkins. 2000. Antimicrobial resistance of Neisseria meningitidis in the United States, 1997. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30:212-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saez-Nieto, J. A., R. Lujan, S. Berron, J. Campos, M. Vinas, C. Fuste, J. A. Vazquez, Q.-Y. Zhang, L. D. Bowler, J. V. Martinez-Suarez, and B. G. Spratt. 1992. Epidemiology and molecular basis of penicillin-resistant Neisseria meningitidis in Spain: a 5-year history (1985-1989). Clin. Infect. Dis. 14:394-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woods, C. R., A. L. Smith, B. L. Wasilauskas, J. Campos, and L. B. Givner. 1994. Invasive disease caused by Neisseria meningitidis relatively resistant to penicillin in North Carolina. J. Infect. Dis. 170:453-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]