Over 100 variants of the TEM β-lactamase, many of which display an extended-spectrum or inhibitor-resistant phenotype, have been identified (http://www.lahey.org/Studies/temtable.asp) (1, 2, 5). They are all variants of TEM-1 or TEM-2, which are encoded by three of the earliest bacterial resistance transposons to be identified, namely Tn1 (6), Tn2 (8), and Tn3 (9). The blaTEM-1a and blaTEM-1b variants, found in Tn3 and Tn2, respectively, differ by three nucleotides but encode identical TEM-1 proteins (3, 4). The blaTEM-2 variant in Tn1 differs by five or six nucleotides from the blaTEM-1 types, and TEM-2 differs from TEM-1 by a single amino acid change, Q39K (4). Though information on the genetic context of blaTEM genes would be valuable in understanding how this important resistance gene is disseminated, little or no sequence beyond the ends of the gene is available for most TEM variants.

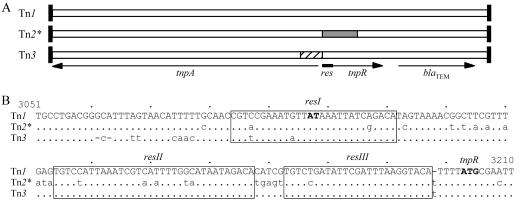

Tn3 from R1 (GenBank accession no. V00613) (7) and Tn1 from RP1/RP4 (L27758) (10) have been completely sequenced and, in addition to the blaTEM gene, they include transposase and resolvase genes, tnpA and tnpR, and a resolution site, res (Fig. 1A). Recently, we reported the sequence of a related transposon (98 and 97% identical to Tn1 and Tn3, respectively) from a multiresistance plasmid (AY123253) (11), part of which is identical to the 1.516 kb of sequence that is available for the original Tn2 from RSF1030 (X54607) (3, 4). As the remaining sequence may also be identical, we designated this transposon Tn2* (11).

FIG. 1.

Mosaic nature of Tn2* and related transposons. (A) Overall structure. The boxes represent Tn1, Tn2*, and Tn3 as indicated, with vertical bars at the ends representing the 38-bp inverted repeats. The positions of the genes and the res site are shown below. Open areas indicate regions where there are few differences between Tn1, Tn2*, and Tn3 sequences. The shaded and hatched areas indicate the regions of difference. (B) Comparison of the sequences of the res regions. Tn1 is shown on top, with the differences found in Tn2* and Tn3 on the lines below. The numbers above the sequences indicate the positions in the Tn1 sequence, where 1 is the first base of the inverted repeat at the tnpA end. The three res subsites (12) are boxed, and their names are indicated above each box. The AT dinucleotide in resI, at which the resolvase-mediated crossover occurs, and the ATG start codon of the tnpR gene are shown in boldface type.

A comparison of the complete sequences of Tn1, Tn2*, and Tn3 revealed that the differences between them are not distributed randomly (Fig. 1A). They are about 99% identical to each other over most of their 4.95-kb lengths, with most of the differences (94 of 150) confined to a region close to the res site. Between positions 2845 and 3104 (Fig. 1A, hatched area), Tn3 shares only 83.8 and 83.1% identity with Tn1 and Tn2*, respectively. For Tn2*, the adjacent region (positions 3107 to 3493) (Fig. 1A, shaded area) is only 87.2 and 87.5% identical to Tn1 and Tn3, respectively. The boundary between these two regions (Fig. 1B) coincides with the AT dinucleotide in resI, at which resolvase-mediated recombination occurs (12), implicating resolution in the generation of these mosaic structures. The location of the other end of each region is less sharply defined, suggesting the involvement of a homologous recombination step.

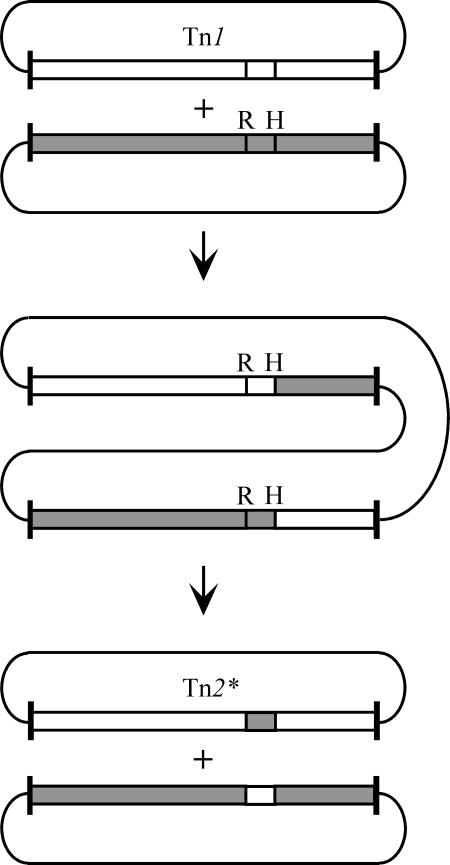

Though other explanations are possible, a simple way to generate these mosaics, for example from Tn1, is by acquisition of a short region from a hypothetical related transposon. This acquisition requires two steps, as shown for Tn2* in Fig. 2. Homologous recombination between transposons on different DNA molecules, occurring at position H, would generate a single molecule containing two hybrid transposons. Subsequent resolution at position R would reseparate the DNA molecules and form Tn2* plus the reciprocal mosaic. This order is required because recombining res sites must be on the same DNA molecule (see 12). Tn3 could be generated in a similar way if the initial homologous recombination occurred on the opposite side of res. Equivalent events could produce further mosaic transposons. These findings highlight the involvement of both homologous and resolvase-mediated recombination in the evolution of transposons.

FIG. 2.

Scheme for generation of Tn2* by a combination of homologous and resolvase-mediated recombination. Tn1 and a hypothetical but related transposon are shown as open and shaded boxes, respectively. The vertical lines labeled H and R indicate the positions of the homologous and resolvase-mediated recombination events, respectively.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bush, K., and G. Jacoby. 1997. Nomenclature of TEM β-lactamases. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 39:1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaibi, E. B., D. Sirot, G. Paul, and R. Labia. 1999. Inhibitor-resistant TEM β-lactamases: phenotypic, genetic and biochemical characteristics. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 43:447-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen, S. T., and R. C. Clowes. 1987. Variations between the nucleotide sequences of Tn1, Tn2, and Tn3 and expression of β-lactamase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 169:913-916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goussard, S., and P. Courvalin. 1991. Sequence of the genes blaT-IB and blaT-2. Gene 102:71-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goussard, S., and P. Courvalin. 1999. Updated sequence information for TEM β-lactamase genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:367-370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hedges, R. W., and A. E. Jacob. 1974. Transposition of ampicillin resistance from RP4 to other replicons. Mol. Gen. Genet. 132:31-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heffron, F., B. J. McCarthy, H. Ohtsubo, and E. Ohtsubo. 1979. DNA sequence analysis of the transposon Tn3: three genes and three sites involved in transposition of Tn3. Cell 18:1153-1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heffron, F., R. Sublett, R. W. Hedges, A. Jacob, and S. Falkow. 1975. Origin of the TEM β-lactamase gene found on plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 122:250-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kopecko, D. J., and S. N. Cohen. 1975. Site-specific recA-independent recombination between bacterial plasmids: involvement of palindromes at the recombinational loci. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:1373-1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pansegrau, W., E. Lanka, P. T. Barth, D. H. Figurski, D. G. Guiney, D. Haas, D. R. Helinski, H. Schwab, V. Stanisich, and C. M. Thomas. 1994. Complete nucleotide sequence of the Birmingham IncPα plasmids. Compilation and comparative analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 239:623-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Partridge, S. R., and R. M. Hall. 2004. Complex multiple antibiotic and mercury resistance region derived from the r-det of NR1 (R100). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4250-4255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherratt, D. 1989. Tn3 and related transposable elements: site-specific recombination and transposition, p. 163-184. In D. E. Berg and M. M. Howe (ed.), Mobile DNA. American Society for Microbiology, Washington D.C.