Abstract

Design of biomaterials for cell-based therapies requires presentation of specific physical and chemical cues to cells, analogous to cues provided by native extracellular matrices (ECM). We previously identified a peptide sequence with high affinity towards apatite (VTKHLNQISQSY, VTK) using phage display. The aims of this study were to identify a human MSC-specific peptide sequence through phage display, combine it with the apatite-specific sequence, and verify the specificity of the combined dual-functioning peptide to both apatite and human bone marrow stromal cells. In this study, a combinatorial phage display identified the cell binding sequence (DPIYALSWSGMA, DPI) which was combined with the mineral binding sequence to generate the dual peptide DPI-VTK. DPI-VTK demonstrated significantly greater binding affinity (1/KD) to apatite surfaces compared to VTK, phosphorylated VTK (VTKphos), DPI-VTKphos, RGD-VTK, and peptide-free apatite surfaces (p < 0.01), while significantly increasing hBMSC adhesion strength (τ50, p < 0.01). MSCs demonstrated significantly greater adhesion strength to DPI-VTK compared to other cell types, while attachment of MC3T3 pre-osteoblasts and murine fibroblasts was limited (p < 0.01). MSCs on DPI-VTK coated surfaces also demonstrated increased spreading compared to pre-osteoblasts and fibroblasts. MSCs cultured on DPI-VTK coated apatite films exhibited significantly greater proliferation compared to controls (p < 0.001). Moreover, early and late stage osteogenic differentiation markers were elevated on DPI-VTK coated apatite films compared to controls. Taken together, phage display can identify non-obvious cell and material specific peptides to increase human MSC adhesion strength to specific biomaterial surfaces and subsequently increase cell proliferation and differentiation. These new peptides expand biomaterial design methodology for cell-based regeneration of bone defects. This strategy of combining cell and material binding phage display derived peptides is broadly applicable to a variety of systems requiring targeted adhesion of specific cell populations, and may be generalized to the engineering of any adhesion surface.

Keywords: Biomimetic apatite, peptides, phage display, MSCs, adhesion strength

Introduction

Regeneration of large, clinically relevant volumes of tissue in vivo using transplanted cells is dependent on having a biomaterial carrier with surface properties that maximize cell attachment and promote cell growth, differentiation and formation of functional extracellular matrix (ECM) (1,2). Additionally, designing a biomaterial that can promote adhesion of specific cell populations can improve the efficiency of cell based therapies (3). In the context of bone tissue engineering, inorganic biomaterials, mineralized synthetic or natural polymers, and polymer-mineral composites are used to deliver physical and chemical cues to drive cell adhesion and osteogenesis (4–6). For example, functionalizing mineralized biomaterials with ECM proteins increases cell attachment, proliferation and differentiation, leading to increased bone healing (7–9).

Peptides derived from the functional domains of ECM proteins can direct stem and progenitor cells toward a bone lineage (3,7,10,11). Peptide delivery methods involve adsorption, covalent immobilization or encapsulation into a biomaterial. The method of delivery and modification of the peptide due to cyclization, post-translational modification or combination with other peptides play important roles in mediating cell responses (12). Adsorption is the primary mode of peptide delivery to mineral surfaces since covalent immobilization is not possible. Therefore, the accessibility of cell binding domains once the peptide is delivered to a mineral substrate is an important design consideration.

Variability of peptide mediated cell attachment, proliferation, differentiation and tissue regeneration can be linked to both the lack of proper presentation of the peptide to cells and the lack of peptide specificity to certain cell populations (13–15). Many ECM proteins have multifunctional domains that work in conjunction with one another to present cell instructive sequences to cell surface receptors. For instance, multifunctional ECM-derived or designed peptides such as GTPGPQGIAGQRGVV (P15) and DpSpSEEKFLRRIGRFG (N15)-PRGDS, respectively, demonstrate cell and mineral binding affinity, and impart ostoconductive and ostoinductive cues to adherent osteogenic cells (14,16). P15, with a sequence similar to one found in the a1 chain of type I collagen, accelerates bone formation in-vivo and has advanced to the clinic in a variety of applications, including healing of periodontal defects, sinus augmentation, alveolar ridge augmentation, fracture healing and lumbar fusion (17–20).

In addition to a cell binding sequence, incorporating a second sequence that tethers the peptide to a biomaterial can mimic these ECM multifunctional domains. Material binding domains have been combined with BMP and VEGF derived peptides to increase adsorption to biomineral surfaces, which in turn can increase cell proliferation, differentiation and drive osteogenesis (9,11,21,22). Combining cell adhesive peptides with material specific binding domains may allow for greater control of peptide parameters that influence cell recognition. In addition to changing the structure of a peptide, a dual functioning peptide having a material adsorption component can control the presentation of the cell binding sequence to cell surface receptors via both the cell and material binding domains (9,21).

In order to mediate cell specific interactions on apatite surfaces, we used phage display to identify a peptide sequence with high affinity and specificity of binding towards apatite (VTKHLNQISQSY, VTK), especially when phosphorylated (23). The primary aims of this study were to use phage display to identify a human bone marrow stromal cell (hBMSC) specific sequence, combine it with VTK and measure apatite binding affinity, hBMSC adhesion strength, and specificity to hBMSCs when the apatite and cell-specific peptides are combined into a dual functioning peptide.

Materials and Methods

Biomaterial preparation

Hydroxyapatite disks (HAP) for the phage display experiments (10 mm diameter x 4 mm thick) were pressed from powder (Plasma Biotal Ltd. P220) at 1 metric ton for 1 minute and sintered at 1350°C for 5 hours (heating rate of 10°C/minute). Biomimetic apatite films with a non-stoichiometric apatite surface similar to the inorganic bone micro-environment were used to characterize cell attachment. Apatite films were prepared by immersing 85:15 polylactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA, Alkermes) thin films in a simulated body fluid to precipitate carbonate substituted apatite with plate like nanofeatures. A 5 w/v% PLGA-chloroform solution was cast on 15 mm diameter glass slides. The PLGA films were etched in 0.5M NaOH and immersed in modified simulated body fluid (mSBF) for 5 days at 37°C with fluid changes every 24 hrs. The mSBF was made by dissolving the following reagents in Millipore water at 25°C and titrating to pH 6.8 using NaOH: 141 mM NaCl, 4.0 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MgSO4, 1.0 mM MgCl2, 4.2 mM NaHCO3, 5.0 mM CaCl2•2H2O, and 2.0 mM KH2PO4.

Cell sources and culture

MSCs from various sources (human, mouse primary, human iPS), osteoblasts and fibroblasts were used to assess specificity of peptides to cells. Clonally derived human bone marrow stromal cells (hBMSC) were a generous gift from the NIH (24,25). Murine bone marrow stromal cells (mBMSCs) were harvested from femora and tibiae of 5–6 week old female C57/BL6 mice (Jackson Laboratories). All BMSCs were cultured in alpha minimum essential media (α-MEM) (Gibco, #12561) with glutamine containing 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics (100 U/mL penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin (P/S)) (Gibco, #15140) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Induced pluripotent stem cell derived MSCs (iPS-MSC) were a generous gift from Dr. Paul Krebsbach. iPS-MSCs were cultured in (α-MEM), 20% FBS, antibiotics, 200mM L-glutamine, and 10mM non-essential amino acids. MC3T3-E1 and mouse dermal fibroblasts (MDFs) were a gift from Dr. Renny Franceschi. MC3T3-E1 cells and mouse dermal fibroblasts were cultured in alpha minimum essential media (α-MEM), 10% FBS, and antibiotics. All cells were passaged when they reached 80–90% confluence. Media was replaced every 2–3 days.

Combinatorial phage display and screening for hBMSC specific peptides

Peptide sequences with affinity for hBMSCs were identified by screening the Ph.D.12™ Phage Display Library (New England Biolabs, #E8110S), consisting of 109 different phage with 12-mer amino acid linear peptide inserts, against clonally derived hBMSCs (Passage 3–6). 2×104 hBMSCs were plated in 2 wells of a 6-well dish and cultured for 6 days in culture media at 37°C and 5% CO2. After 6 days of culture, the NEB 12-mer peptide library was prescreened against sintered HAP disks prior to introduction to the cells, to preferentially screen for sequences attracted to the cells and not the apatite. A streptavidin control was run in a separate dish per the manufacturer’s protocol.

Plated cells in 6-well dishes were rinsed 2X with phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Gibco #10010) and pre-blocked with α-MEM containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) without supplements at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 30 minutes. The aliquot of phage harvested from the HAP disks was then introduced to the cells (n=2). Non-binding phage were then discarded, and the cells were washed 5X in cold PBS. The phage bound to the cells was eluted with 1 mL of Glycine/HCl, pH 2.2, with 1 mg/mL BSA for 10 minutes at room temperature while being gently rocked. The eluted phage was collected and neutralized with 1M Tris-HCl, pH 9.1. Three rounds of panning were performed for each sample.

RELIC analysis

The bioinformatics tool REceptor LIgand Contacts (RELIC) (26–28) was used to analyze the data from the phage display. The programs DNA2PRO, MOTIF1, and INFO determined peptide translation sequences from DNA code, continuous conserved motifs within the peptide population allowing for conservative substitutions, and information numbers for each peptide reflecting the probability of selecting individual phage by chance, respectively. The phage display experiment on hBMSCs yielded 50 candidate peptides, which were subsequently used in the MOTIF1 and INFO programs. The program MOTIF1 searched for 3-mer and 4-mer continuous conserved motifs. The program INFO was run with subtraction of a random selection of phage from the parent library (12R, 441 random sequences from NEB 12-mer Ph.D. kit).

Phage immunohistochemistry labeling and scoring

1×104 hBMSC cells (Passage 5–6) were grown to confluence, and prior to phage introduction, the media was removed and the cells were incubated with 500μL of α-MEM containing 0.1% BSA overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2. Phage plaques selected based on RELIC analysis (Table 1, 1st column) were introduced to this culture medium at a concentration of 0.5 × 1011 pfu/100μL and allowed to mix gently for 2 hours at 37°C in 5% CO2. The media with phage was removed, and the cells were washed 6X with PBS. The cells were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences #15710) in PBS for 10 minutes and washed 2X with PBS. Half of the fixed slides for each peptide were treated with 0.1% saponin in 0.1% BSA:PBS. All fixed slides were incubated with mouse anti-M13 monoclonal antibody (GE Healthcare, #27-9420-01) diluted to 1:250 in PBS for 1 hour. The cells were washed 3X with PBS, and then incubated with FITC-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., #515-095-003) diluted 1:250 in PBS for 1 hour, covered from light. The cells were again washed 3X in PBS and allowed to soak in PBS overnight. The antibody solution, PBS wash solution, and PBS overnight soak solution for the saponin treated slides contained 0.1% saponin.

Table 1.

Immunhistochemistry scoring

| Phage with Peptide Sequence Tested | Information Level | Average Score Without Saponin | Averge Score With Saponin | Combined Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YPLRPNAESLRF | high | 1.00 | 1.50 | 2.50 |

| DPIYALSWSGMA* | high | 2.17 | 2.83 | 5.00 |

| NATHLTADHVNK | high | 1.67 | 2.00 | 3.67 |

| YPSAPPQWLTNT | high | 1.50 | 1.67 | 3.17 |

| AQHIRSWDGFSH | high | 0.00 | 1.50 | 1.50 |

| LPLYTSPDKPGK | high | 1.67 | 2.00 | 3.67 |

| SILNYPTNPGIA | high | 2.33 | 2.17 | 4.50 |

| LLADTTHHRPWT | high | 2.00 | 1.50 | 3.50 |

| HPIRVQPDWGFL | high | 1.83 | 1.33 | 3.17 |

| VETHTTQWLITEV | high | 1.83 | 2.50 | 4.33 |

| TPMGRPHPETPA | low | ** | 1.33 | 1.33 |

| SGKTSLISHAAL | low | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.17 |

| NHLPLPPPAATM | low | ** | 1.17 | 1.17 |

| SDTQMPPAXGRA | low | 0.33 | 2.17 | 2.50 |

| GYLPLHSITYRP | low | 1.83 | 1.50 | 3.33 |

| QLLEPVNLSTGP | low | 1.83 | 1.33 | 3.17 |

| WHPPKGLSPLPD | low | 0.67 | 1.33 | 2.00 |

| FRLPGSLINHPQ | low | 1.33 | 2.17 | 3.50 |

| SILSTMSPHGAT | low | 0.00 | 0.83 | 0.83 |

| NYNPHNPFPPAP | low | 1.67 | 0.67 | 2.33 |

Peptide sequence chosen as best preferential binder to hBMSC

Cells washed away during rinsing and could not be scored

Cells were covered with a glass coverslide after preparing in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories H-1200), and were subsequently viewed on a confocal laser-scanning microscope at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm (Nikon TE 3000 Inverted Microscope). For phage immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis, a BioRad Radiance 2000 LaserSharp program was used to image 20 μm into the depth of the cells at 2 μm intervals under 20x magnification. An excitation wavelength of 568 nm was used to obtain similar series of images to identify the cells in the background without exciting the FITC attached to the phage. Each series of images was compiled in the LaserSharp program to obtain images showing adhesion of phage onto or into cells. Controls included: cells without phage receiving both antibody and FITC, and cells only to detect any background fluorescence. Two samples for each phage and each condition were imaged. Three individual scorers blinded to the phage number and saponin treatment scored each image on a scale of 0–3 (3 having the most stain present). The 3 independent scores (n = 2 each) were averaged, and phage having the highest stain present in both saponin treatments were further considered. The combined IHC score was taken as the addition of scores with and without saponin.

Peptide synthesis

Single and dual function experimental and control peptides were synthesized using solid phase synthesis and protective chemistry (Table 2). High performance liquid chromatography was used to verify > 95% purity. Peptides were stored at −20++C until use in each experiment.

Table 2.

Peptide Properties

| Peptide | Sequence | Description | MW (g/mol) | Net Charge | Acidic residues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VTK | VTKHLNQISQSY | Phage derived mineral binding sequence | 1417.59 | 1 | 2 |

| VTKphos | VTKHLNQI(Sp)Q(Sp)Y | Phosphorylated phage derived mineral binding sequence (control) | 1577.55 | −3 | 2 |

| RGD | GRGDS | Cell binding control | 346.34 | 0 | 1 |

| DPI | DPIYALSWSGMA | Phage derived cell binding sequence | 1310.49 | −1 | 3 |

| DPI-VTK | GGDPIYALSWSGMAGG GSVTKHLNQISQSY | Dual functioning phage derived peptide | 3025.35 | 0 | 5 |

| DPI-VTKphos | GGDPIYALSWSGMAGG GSVTKHLNQI(Sp)Q(Sp)Y | Dual functioning peptide w/mineral binding control sequence | 3185.31 | −5 | 5 |

| RGD-VTK | GGRGDGGGSVTKHLNQI SQSY | Dual functioning peptide w/cell binding control | 2061.20 | 1 | 3 |

| RGD-E7 | EEEEEEEPRGDT | Dual functioning peptide control | 1448.00 | −7 | 8 |

Langmuir isotherms

Peptides were solubilized in water and diluted in Trizma buffer (pH 7.5). Photometric readings for peptide standard curves and samples were taken at 25°C using a multi-well plate reader measuring UV absorbance from 205–240 nm at 5 nm increments. The absorbance wavelength that produced the best linear curve fit for standards was used to calculate sample concentrations before and after the adsorption assay. This wavelength varied between 205–215 nm for single peptides and 230–235 nm for dual peptides. Isotherm experiments were conducted using HAP powder (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) with an average particle size of 18–30 μm and a surface area of 50 m2/g suspended in Trizma buffer pH 7.5 for 2–3 hours at 37°C prior to experiments. A powder presents a relatively high surface to volume ratio allowing less peptide usage in a smaller volume.

Adsorption assays were conducted by incubating an HAP suspension and peptide solution in a 96-well Millipore filter plate for 3 hours at 37°C under agitation. A standard curve was also generated for each peptide binding experiment, where the solution was incubated with an equivalent volume of Trizma instead of the HAP suspension. This standard curve was run to account for any potential loss of peptide to the Millipore plate as well as account for any Trizma volume lost to the Millipore filter plate. The experimental solution and the solution associated with the standard curve were filtered into a fresh 96-well plate and the amount of unbound peptide was determined using UV absorbance and standards. Bulk peptide concentrations ranged from 0–2000 μg/mL. Material specific peptides demonstrated no affinity towards tissue culture polystyrene surfaces, negating the possibility of non-specific binding. To assess peptide affinity to apatite, Langmuir isotherms of bulk versus bound peptide were constructed and linearized to determine binding affinity (1/KD) and maximal adsorption concentration (Vmax) using the following equation: (29,30)

where Cb is the bulk concentration of peptide and Cs is the concentration of peptide bound to substrate, and KD is the dissociation constant. Vmax and KD were calculated from the slope and intercept of the linearized curves. Two experiments were done, each with 3 replicates (n=6). The Gibbs free energy of adsorption was calculated using the following equation (31):

where the gas constant (R) = 8.314 J mol−1 K−1, ambient temperature (T) = 310 K, and the molar concentration of solvent water, Csolv = 55.5 mol L−1.

Cell adhesion assays

Biomimetic apatite films were incubated in ddH2O overnight to remove excess salts, and then incubated in Trizma buffer prior to use. Mineralized films were attached to the bottom of 24 well plates with adherent carbon tabs (Ted Pella, Inc). Films were subsequently incubated in 100 μg/mL of peptide solution for 3 hrs, washed and blocked with 1% denatured BSA to reduce non-specific cell attachment. The amount of peptide on apatite coated films was quantified using UV absorbance and a BCA assay. Loading efficiency on biomimetic apatite was not significantly different across peptide groups (Fig. S2). Cell centrifugation assays using hBMSCs, IPS-MSCs, mBMSCs, MC3T3s and MDFs were conducted using a seeding density of 35,000 cells/cm2.

Peptide coated films, no peptide controls, and films used for standard curves were incubated with cells for 3 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2 in serum-free media. Peptide coated films and no-peptide controls were subsequently washed, wells were filled with PBS, inverted, sealed and centrifuged with forces of 0 – 10−5 dynes using an Eppendorf 5810r centrifuge for 5 minutes (32,33). At forces above 10−5 dynes, mineral and FITC-BSA were washed away. Detached cells were removed, and cell numbers on peptide coated films, no peptide controls and standard curves were determined using the WST-1 assay (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.). A standard curve was constructed for each cell type each time an experiment was run. Adherent cell fractions on peptide coated apatite groups were normalized to no-peptide apatite film controls at each centrifugation speed. Half-cell detachment forces (τ50), the force at which 50% of the cells detach, were calculated by fitting the remaining adherent cell fraction (%) to sigmoidal curves using the Boltzmann equation.

Where L1 = lower asymptote, L2 = upper asymptote, x0 is the inflection point, and dx is the slope at the inflection point. A least squares regression, with unbounded constraints on X0 allows for determination of these parameters.

Cell proliferation and differentiation

Cells were cultured on peptide coated apatite or non-peptide coated controls for 0.75, 3, 7, and 10 days in complete media. Media was changed every 2 days and cell numbers were quantified using the WST-1 assay (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.). Cells were differentiated for 0, 3, 7, 10, 14, 21, 28 days in complete media containing osteogenic factors (10−8M Dexamethasone, 2–5mM β-glycerophosphate, 10−4 M ascorbic acid). Samples were collected (n=3, 6 biological replicates pooled pairwise) in TRIZOL® (ThermoFisher Scientific), homogenized, phase-separated in chloroform, and RNA was precipitated in 500μL isopropanol. RNA was subsequently washed in 80% ethanol, dried and dissolved in RNA grade double distilled water (Milipore) at 70°C. The amount of RNA was measured using a spectrophotometer and 1μg was used for reverse transcription using SuperScript II reagents (ThermoFisher Scientific). TaqMan® Universal PCR Master Mix and Taqman® primer probes (Runx2, Hs00231692_m1;OSX, Hs01866874_s1; ALP, Hs00758162_m1; OCN, Hs01587814_g1) were used for all qRT-PCR reactions. Cycle threshold (CT) values were normalized to GAPDH(Hs02758991) expression and day zero values for each gene were used to calculate ΔΔCT values. Gene expression was expressed as fold change 2−Δ ΔCT. Although gene expression levels were calculated for all timepoints, earlier timepoints (d3-15) are presented for Runx2 and OSX (early markers of osteogenic differentiation), whereas later time points (d10-28) are presented for ALP and OCN (later markers of differentiation).

Cell morphology and immunohistochemistry

Mineralized peptide coated and uncoated controls containing adherent cells (35,000 cells/cm2) from detachment force assays (0 dynes) were washed twice in PBS, fixed in 10% formalin buffer, permeabilized in Triton X, stained with Rhodhamine-Pholloidin (ThermoFisher Scientific) for F-Actin and mounted in Vectashield containing DAPI (Vectorlabs) on glass coverslips. Images were acquired with a NIKON Ti-Eclipse Confocal Microscope using a 20x objective. Images from 4 samples per group and 10 fields per sample (treated as n=40 individual samplings) were analyzed using Image J software (NIH). Each field was analyzed for cell number using the DAPI stain, total cell spread area marked by F-actin stain, and total cell spread area per cell was calculated from the initial two measurements.

Statistical methods

Single factor ANOVA was used to determine differences in binding affinity, half-cell detachment forces and quantitative histomorphometry amongst the different peptides using SigmaPlot 13.0 (Systat Software Inc). Two-way ANOVA with Tukey tests for pairwise comparisons was used to analyze cell proliferation and differentiation (peptide x time).

Results

Phage display on hBMSCs

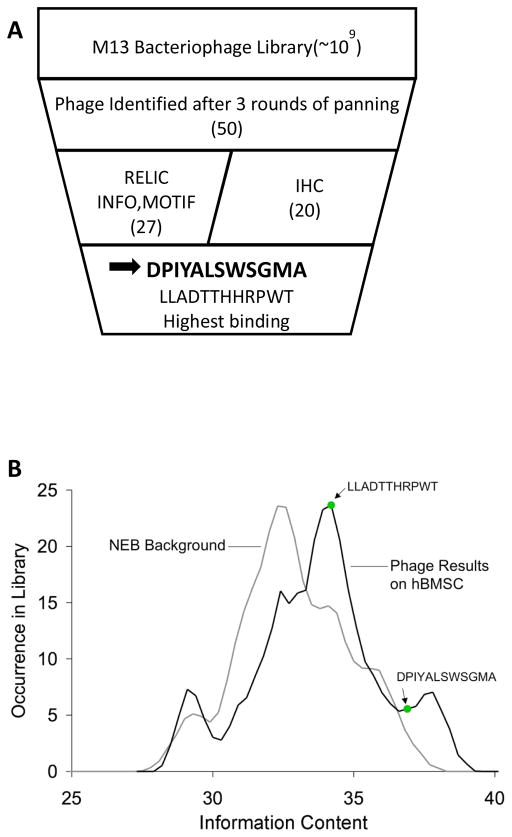

Phage display identified 50 high binding sequences which were subsequently screened using the RELIC informatics tools and immunohistochemistry (Fig 1a). The INFO analysis revealed a shift towards higher information content in the phage identified as binders to hBMSCs, compared to the NEB background (Fig. 1b). Higher information content describes a peptide sequence less likely to occur by chance. For the set of 50 peptides, a peptide sequence was deemed a higher information clone if the information measure was greater than 33.5, and 27 of the 50 peptides were labeled as high information clones. The shift towards higher information content shows that the successive rounds of panning isolated a unique pool of phage bound to the hBMSCs; however, the results from both the MOTIF1 and INFO show that one unique sequence was not identified. Rather, multiple sequences with high information and shared motifs were identified. A subset of 20 sequences, 10 higher information clones and 10 lower information clones, were therefore analyzed using immunohistochemistry. All 20 sequences contained shared motifs.

Figure 1.

Combinatorial phage display on clonally-derived human bone marrow stromal cells. A) Schematic displaying data analysis progression used to identify peptides that preferentially adhere to clonally derived hBMSCs. B) INFO content values calculated in RELIC for NEB background and phage subset identified as preferential binders to clonally derived hBMSCs. High information content correlates to a lower incidence of being selected by chance. The phage subset shows a shift towards a higher information content signifying this subset was selected based on the binding affinity to hBMSCs. The INFO values of the two phage sequences, LLADTTHHRPWT and DPIYALSWSGMA, used in the final dual-functioning peptide design are labeled on the graph. C) Consensus sequences from the MOTIF1 program showing (S/T)(I/V)LS and NHT as the 4- and 3-mer motifs having the most frequent hits. Peptides DPIYALSWSGMA and LLADTTHHRPWT are included to show sequence homology with the 4- and 3-mer motifs identified via MOTIF1.

From the 50 candidate sequences derived from phage display, the MOTIF1 program identified continuous motifs 3 and 4 amino acids long as NHT, and (S/T)(I/V)LS, respectively (Fig. 1c). The motif NHT was present in 6% of the peptides, whereas (S/T)(I/V)LS was present in 12%. The streptavidin control yielded the consensus HPQ sequence, signaling successful panning.

The peptide sequence, DPIYALSWSGMA, had the highest combined IHC score (Table 1). The higher information clones had an average combined score of 3.50 ± 1.01, whereas the lower information clones had an average combined score of 2.23 ± 1.20. RELIC INFO analysis (Fig. 1b), RELIC MOTIF frequency data showing amino acid frequency by position (Fig. 1c), and IHC scoring (Table 1) collectively identified two hBMSC preferential binding sequences: DPIYALSWSGMA [DPI] and LLADTTHRPWT [LLA]. Phage expressing DPI and LLA show positive binding to hBMSCs with and without saponin (Table 1). Peptide and cell attachment assays demonstrated greater DPI-VTK adsorption to apatite and greater MSC attachment to peptide coated apatite surfaces compared to LLA-VTK and controls (Fig. S1). DPI was therefore used to construct the dual functioning peptides.

Peptide binding isotherms on HAP

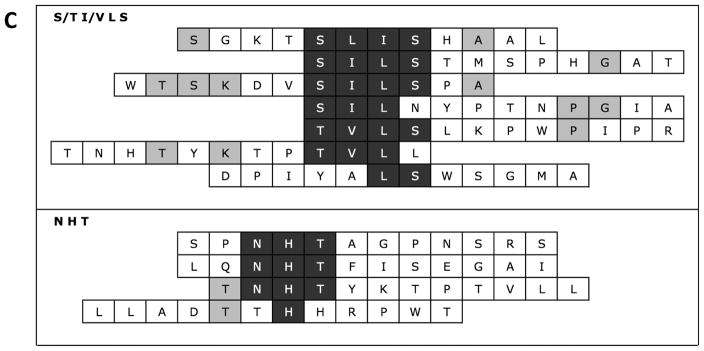

Mineral binding and mineral + cell binding peptides reached an adsorption equilibrium between 0–1000 μg/mL, indicating saturation on apatite (Fig. 2a,b). The phosphorylated mineral specific sequence VTKphos demonstrated a significantly greater binding affinity to apatite than VTK (Table 3). The dual-functioning phage derived peptides DPI-VTK (p<0.001), DPI-VTKphos (p < 0.01) and dual functioning peptide with cell binding control RGD-VTK (p < 0.01) demonstrated significantly higher binding affinities than the single peptides. DPI-VTK had a higher binding affinity than DPI-VTKphos (p < 0.01). Although the acidic residues in E7 bind strongly with the cationic components of HAP, the binding affinity of RGD-E7 was lower than predominantly charge neutral RGD-VTK and DPI-VTK (p<0.01).

Figure 2.

Langmuir isotherms of A) mineral binding and B) dual functioning peptides on hydroxyapatite. Cb is the bulk concentration of peptide in solution and Cs is the bound concentration of peptide on hydroxyapatite. Data points represent triplicates from 2 separate adsorption experiments (n=6).

Table 3.

Analysis of Linearized Langmuir Isotherm data

| Kd. (μM) | Vmax (μmol/cm2) | ΔGads (kJ)/mol | r2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VTK | 74.57±3.59 | 30.67±5.44 | −34.8 | 0.94 |

| VTKphos | 32.67±1.69* | 21.49±4.35 | −37.0 | 0.93 |

| RGD-E7 | 74.13±3.47 | 328.86±54.39 | −34.9 | 0.95 |

| RGD-VTK | 7.36±0.35** | 4.92±2.56 | −40.8 | 0.90 |

| DPI-VTKphos | 5.04±0.55** | 30.05±6.41 | −41.8 | 0.97 |

| DPI-VTK | 2.68±0.57*** | 17.94±3.22 | −43.4 | 0.93 |

greater binding affinity(1/Kd) compared to RGD-E7 and VTK (p <0.01).

greater binding affinity compared to VTK, VTKphos,RGD-E7 (p<0.01).

greater binding affinity compared to VTK, VTKphos,RGD-E7, RGD-VTK, and DPI-VTKphos (p<0.01).

ΔG=-RT Ln(Csolv/KD); R = 8.314 J mol−1 K−1; T = 310 K; Csolv = 55.5 mol/L

Experimentally measured values for the concentration of peptide required to reach equilibrium, Vmax, (Table 3) were within the range of monolayer adsorption concentrations for proteins and peptides found in the literature (29,30), and calculated Vmax values based on cross-sectional area of each peptide in a linear and cyclic conformation. Vmax was is lower for VTKphos than for VTK. Vmax for single peptides was significantly higher than dual peptides (p < 0.01) with the exception of RGD-E7.

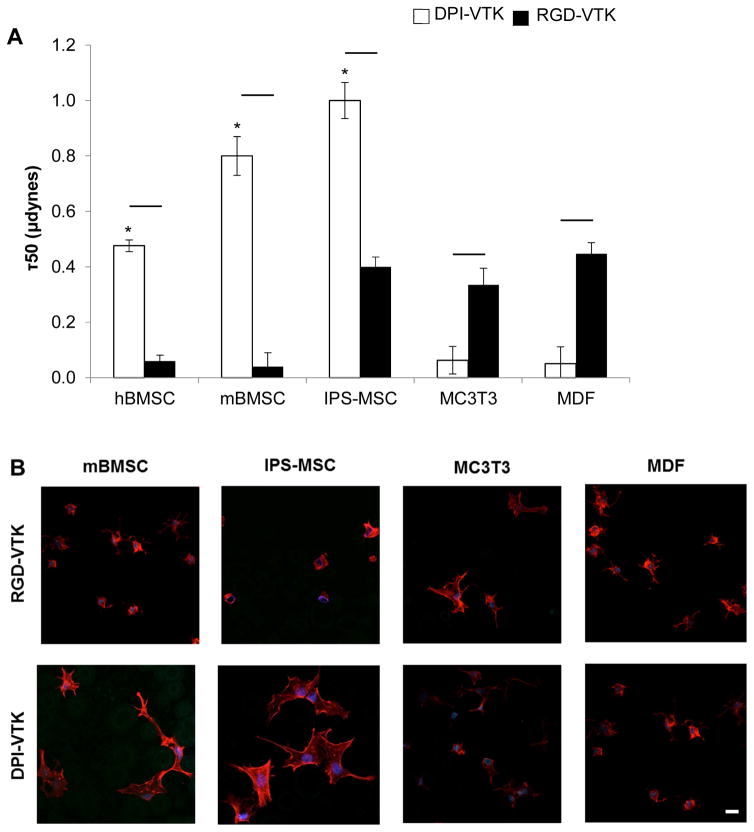

Cell adhesion strength on dual-peptide coated mineral

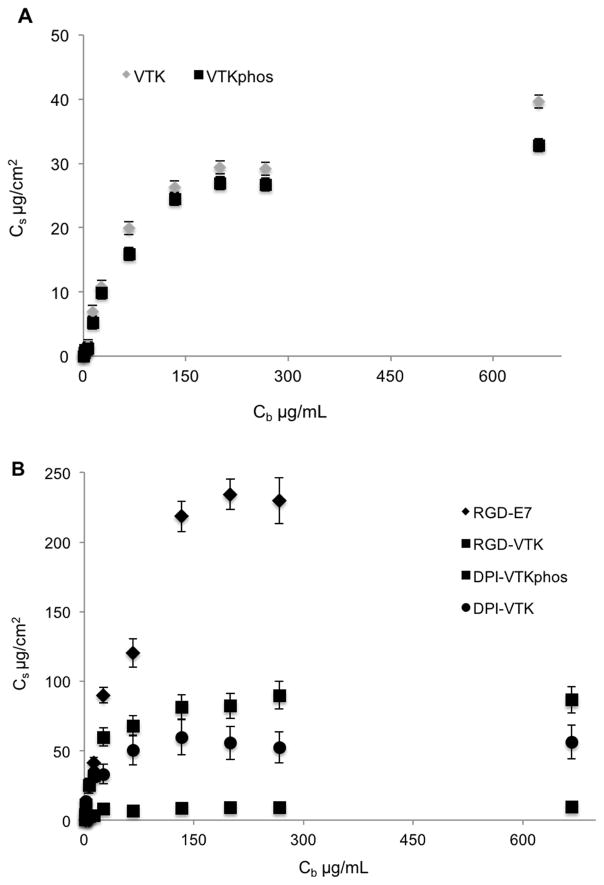

Dual peptides RGD-VTK and RGD-E7 yielded the highest percent cell attachment when no force was applied (Fig. 3a, p < 0.01). However, as forces were applied, larger cell fractions remained adherent to DPI-VTK compared to other peptide coated and control groups (Fig 3b,c). Consequently, τ50 for the DPI-VTK sequence was significantly higher than for the other peptides (Table 4, p < 0.01).

Figure 3.

HBMSC adhesion strength on single and dual-functioning peptide coated apatite films. A) Cell attachment across different peptide groups exposed to a range of detachment forces (n=6) * denotes significant difference from other peptides (p<0.01). Sigmoidal curve-fitting of cell attachment data depicting force at which 50% of the initially adherent cells become detached (n=6) is greater on DPI-VTK compared to B) mineral binding peptides and C) other dual functioning peptides.

Table 4.

Half-cell detachment force for hBMSCs on single and dual functioning peptides and correlation coefficient for fit of data to sigmoidal curve

| τ50 (μdynes) | r2 | |

|---|---|---|

| VTK | 0.05±0.01 | 0.93 |

| VTKphos | 0.05±0.05 | 0.97 |

| RGD-E7 | 0.05±0.47 | 0.94 |

| RGD-VTK | 0.01±0.02 | 0.91 |

| DPI-VTKphos | 0.09±0.02 | 0.95 |

| DPI-VTK* | 0.48±0.02 | 0.94 |

denotes significant difference with respect to other peptides (p <0.01).

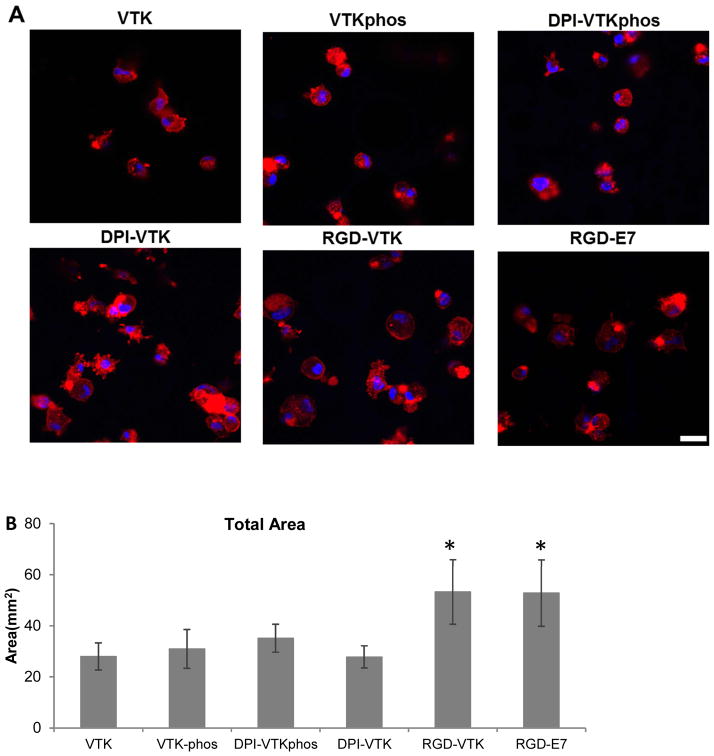

Human BMSCs exhibited a more spread morphology on RGD-VTK, DPI-VTK and RGD-E7 compared to other peptides (Fig. 4a). The total surface area covered by cells was significantly greater on RGD-VTK and RGD-E7 coated surfaces, however, spread area/cell was significantly greater on DPI-VTK compared to RGD-VTK and RGD-E7 (Fig. 4b,c p < 0.01).

Figure 4.

hBMSC spreading (35,000 cells/cm2) on single and dual-functioning peptide coated apatite films. A) Confocal microscopy images at 40x depicting cell spreading on peptide coated apatite films. F-actin labeled with Rho-Pholloidin and nuclei labeled with DAPI. Scale bars 10μm. B) Total cell spread area calculated from Image J analysis of Pholloidin-stained area (n=4 per group x 10 fields of view per sample). * denotes significantlydifferent from unmarked groups (p<0.01) C) Area/cell calculated from Image J (NIH) analysis of Pholloidin-stained area (n=4 per group x 10 fields of view per sample). * denotes significantly different from unmarked groups (p<0.01)

hBMSC specificity to dual-peptide coated mineral

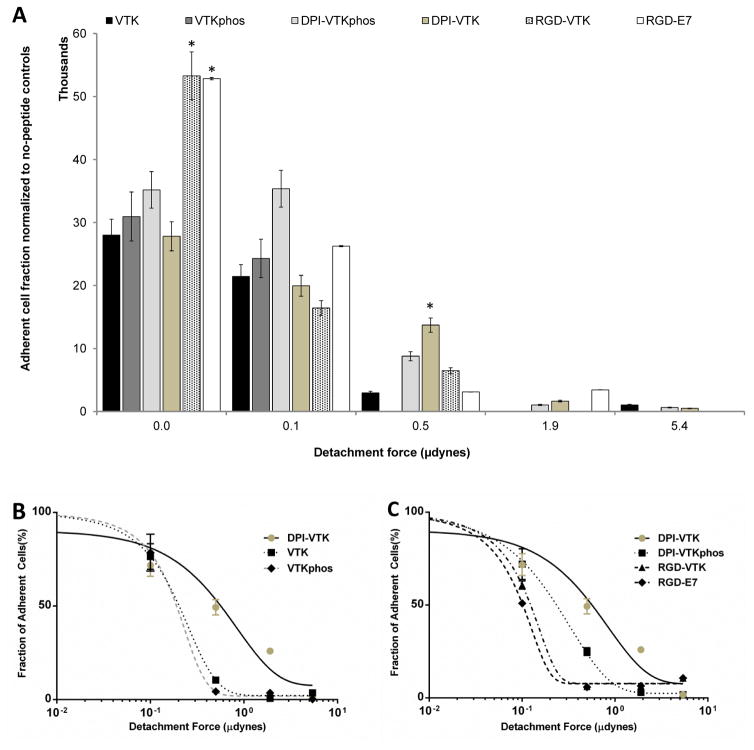

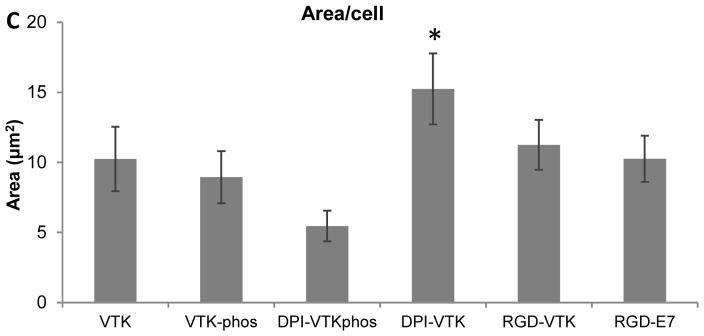

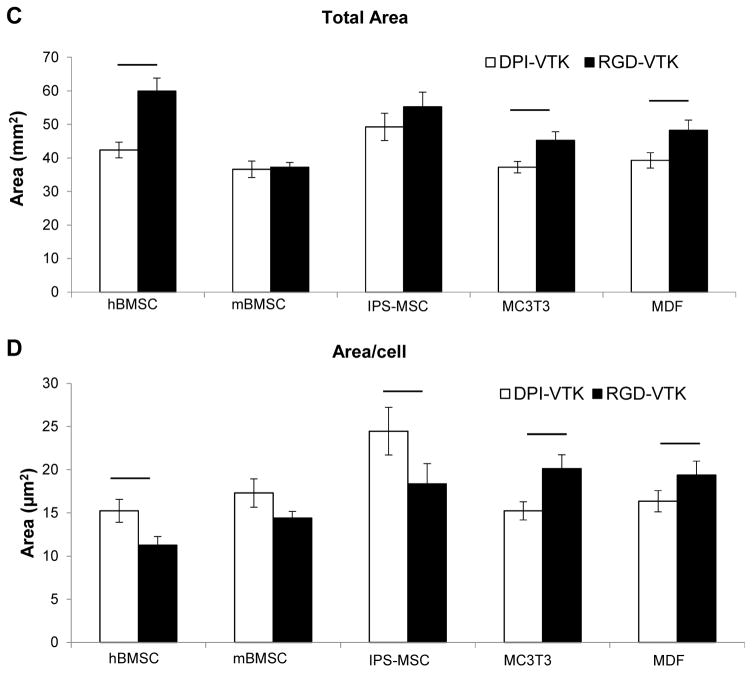

Human BMSCs, mBMSCs and iPS-MSCs bound more strongly to DPI-VTK than murine pre-osteoblasts and fibroblasts (Fig. 5a, p < 0.01). RGD-VTK bound weakly to hBMSCs, however it promoted stronger adhesion to MC3T3s and MDFs than DPI-VTK (p < 0.01). Although iPS-MSC adhesion to DPI-VTK was greater than to RGD-VTK (p < 0.01), iPS-MSCs demonstrated similar adhesion strength on RGD-VTK compared to pre-osteoblasts and fibroblasts.

Figure 5.

MSC specific adhesion and spreading on DPI-VTK and RGD-VTK coated apatite films. A) Half-cell detachment forces (τ50) calculated from sigmoidal curve-fitting of cell attachment data indicating force at which 50% of the initially adherent cells become detached (n=6). Bars denote significant differences between peptide groups (p <0.01). * denotes difference from MC3T3 and mouse dermal fibroblasts in peptide coated groups. B) Confocal microscopy images at 40x depicting spreading on peptide coated apatite films. F-actin labeled with Rho-Pholloidin and nuclei labeled with DAPI. Scale bars 10μm. C) Total cell spread area calculated from Image J analysis of Pholloidin-stained area (n=4 per group x 10 fields of view per sample. Bars denote difference within cell types (p < 0.01). D) Area/cell calculated from Image J (NIH) analysis of Pholloidin-stained area (n=4 per group x 10 fields of view per sample). Bars denote difference within cell types (p < 0.01).

hBMSCs interacting with DPI-VTK and RGD-VTK were more round and less spread compared to mBMSCs and iPS-MSCs (Fig. 5b). MC3T3s and MDFs spread more on RGD-VTK compared to DPI-VTK. Conversely, MSCs spread more on DPI-VTK compared to RGD-VTK. Total cell spread area was significantly greater on RGD-VTK compared to DPI-VTK across all cell types (p < 0.01), with the exception of mBMSCs. However, spread area normalized to number of MSCs was greater on DPI-VTK compared to RGD-VTK (Fig. 5c,d). The converse relationship was observed with MC3T3 and MDFs, indicating that more hBMSCs bound to RGD-VTK, but MC3T3s and MDFs bound and spread more favorably.

MSC proliferation and differentiation on peptide coated apatite

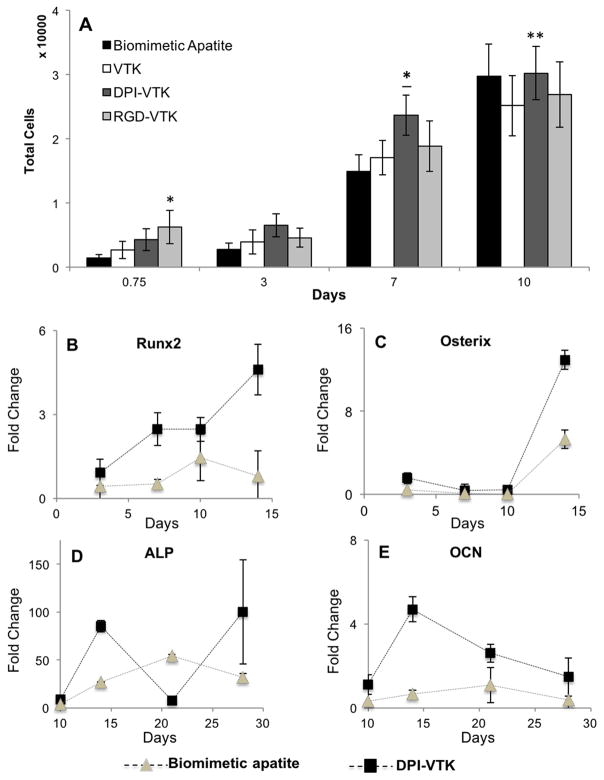

Human MSCs proliferated to a greater extent on RGD-VTK coated apatite at 18 hr compared to biomimetic apatite without peptide (Fig. 6a, p <0.016). However by day 7, the number of cells on DPI-VTK coated apatite was significantlygreater (p < 0.001). Cell numbers on DPI-VTK coated apatite were also significantly higher than on apatite coated with VTK and RGD-VTK on day 10 (p < 0.05). By day 10, cells reached a saturation density beyond which cells entered the lag phase and cell numbers exceeded detection limits.

Figure 6. MSC proliferation and differentiation on peptide coated apatite substrates.

(A) MSC proliferation on peptide coated apatite substrates. * different from apatite control and TCPS (p < 0.001). * Different from apatite control (p <0.001). ** Different from VTK (p < 0.05). (BE) Differentiation of iPS-MSCs on biomimetic apatite and peptide coated apatite. B,C). Relative gene expression of early osteogenic transcription factors Runx2 and OSX normalized to day zero and GAPDH values (n=3). D–E) relative gene expression of genes regulating late stage osteogenic markers ALP and OCN normalized to day zero and GAPDH values (n=3).

Human MSCs were cultured on TCPS to verify osteogenic differentiation potential and relative gene expression levels were expressed as fold changes 2−ΔΔCT (Fig. S3. The osteogenic transcription factor Runx2 is elevated by day 10 followed by an increase in Osterix, indicative of early stage induction of osteogenic differentiation (Fig. S3a,b). Later markers of osteogenic differentiation, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and osteocalcin (OCN), are elevated by day 20 (Fig. S3c,d), which coincides with mineralization (Fig. S3e). Expression of both early and late stage markers for osteogenic differentiation on biomimetic apatite is different from TCPS.. Therefore, mineralized films were used as a baseline for comparing MSC differentiation on peptide coated apatite films (Fig. 6,b-e). Apatite films coated with DPI-VTK had significantly greater Runx2 expression compared to uncoated films (p <0.023). Runx2 expression also peaked more rapidly on DPI-VTK coated substrates (day 7), compared to day 10 on apatite controls (p < 0.05). Cells adherent to DPI-VTK coated apatite had greater OSX expression compared to controls on day 10 (p < 0.001). ALP expression was significantly higher on days 14, 21, and 28 compared to days 3 and 7 across both groups (p <0.001). Finally, OCN expression was significantly higher on DPI-VTK compared to BLM (p < 0.001).

Discussion

Human BMSC specific peptide sequences were discovered using a combinatorial phage display (Table 1, Fig. 1). Apatite-specific peptide sequences were similarly discovered using a combinatorial phage display (27) and, in this study, were combined with cell-specific sequences to create new dual functioning peptides with one domain having preferential affinity for a specific material chemistry and a second domain having preferential affinity for a specific cell population. There are three aspects of this work that are novel and have the potential to have an impact. First, the discovery and use of new, non-intuitive sequences discovered via phage display represents a different design approach compared to the more conventional use of known ECM sequences. Second, the specificity of the phage-derived sequences to the biomaterial and cells of interest represents an advancement over most other sequences, which are non-specific. The modular approach to engineer dual functioning peptides from the phage toolbox is also a component of this new design approach.

Both cell and mineral binding domains contributed to the binding of dual functioning peptides to apatite (Table 3). Combining the two sequences improved both binding affinity and cell adhesion strength compared to the single peptides. Phosphorylation is a common post-translational modification in natural ECM peptides and proteins that interact with mineral (14,23). For example, unphosphorylated domains of dentin phosphoproteins (DPP) are more mobile, flexible, and can fold over HAP surfaces, but the phosphorylated domains drive association with mineral (34). Although phosphorylation drives apatite binding affinity of DPP and osteopontin derived ASARM peptides, it is the glutamic and aspartic acid residues that are involved in binding to the apatite surface (34,35). These data indicate an interplay between sequence, conformation, charge distribution and apatite affinity of phosphorylation, and all of these peptide parameters could contribute to the different apatite affinity of DPI-VTK vs. DPI-VTKphos compared to VTKphos vs. VTK. Moreover, RGD-E7, which has an acidic mineral binding motif, had the lowest binding affinity amongst the dual functioning peptides. The KD values for RGD-E7 (Table 3) are consistent with studies using similar materials and assay conditions (22). Conformational and charge distributions of bound peptide could also contribute to the differences in Vmax. Single peptides can pack more efficiently because of smaller size, however the increased saturation concentration of RGD-E7 could be a result of non-Langmuir kinetics and potential aggregation in the solution state. Taken together, peptide sequence and conformation also contribute to packing efficiency.

The half-cell detachment force is the force at which 50% of the initially bound cell population becomes detached. Detachment forces are a surrogate for how strongly cells attach to the substrate. The strength of attachment is related to the formation of specific peptide and cell surface receptor interactions. Since the adhesion timeframe in serum-free media allows for initial attachment only, the detachment force correlates with the average number of peptide-cell ligand interactions over a population of cells (33). Human BMSCs seeded on the dual-functioning phage derived peptide DPI-VTK had the highest adhesion strength (Table 4). Although cells interacting with VTK and VTKphos exhibited a similar initial attachment as cells interacting with DPI-VTK, they did not exhibit the same adhesion strength as cells interacting with DPI-VTK (Fig. 3b). This indicates that adhesion strength of cells to DPI-VTK is largely driven by the interaction with the DPI domain of the peptide.

The weaker attachment of hBMSCs to DPI-VTKphos compared to DPI-VTK (Table 4) may indicate that phosphorylating the mineral sequence compromises the presentation of the DPI sequence to the cell. Favorable binding to apatite and increased adhesion strength of hBMSCs to DPI-VTK compared to DPI-VTKphos, indicate an indirect effect of the cell specific sequence on mineral association and an indirect effect of mineral sequence on cell association. Adding DPI to the VTK sequence could lead to conformational changes to either the mineral or cell binding sequences that enhance mineral binding affinity. Once bound, association with the biomimetic apatite could cause another structural change in either DPI or VTK, resulting in a change in affinity to cell binding targets.

More hBMSCs were initially bound to RGD-VTK and RGD-E7 compared to DPI-VTK and DPI-VTKphos (Fig. 3a). Cell attachment to these peptides indicates that hBMSC cell surface receptors bind to both DPI and RGD peptides, as expected, and validates the results of the phage display. Although there was less initial hBMSC attachment on DPI-VTK compared to RGD-VTK, DPI-VTK was more favorable for hBMSC spreading (Fig. 4c), a finding supported by the increase in adhesion strength of MSCs on DPI-VTK vs. RGD-VTK (Fig. 3, 5). The prevalence of more spread cells indicates more cell-matrix interactions that result in stronger attachment forces.

The adhesion strength of MSCs to DPI-VTK was greater than to pre-osteoblasts and fibroblasts (Fig. 5a). These data indicate that the phage derived peptide has interactions that are specific to cell-surface receptors on MSCs, and verifies that phage display is capable of yielding cell-specific peptide sequences. Although hBMSCs demonstrated higher initial attachment to RGD-VTK and RGD-E7 (Fig. 3a), the weaker adhesion strength is indicative of weak association between hBMSC binding targets and RGD when presented with either E7 or VTK material binding sequences.

The absence of highly acidic residues in either set of sequences is an unexpected outcome of the phage selection process. VTK and DPI are comprised of 25% and 50% hydrophobic sequences respectively (Table 2, bold letters). Phage display exhibits a selection bias for peptides with hydrophobic sequences (36). Numerous bone ECM derived peptides containing charged or polar residues are thought to drive apatite binding. Although this hydrophobic bias seems counterintuitive for apatite binding, it could be a promising tool for biomolecule delivery. Peptides with charged and acidic residues that react with the defined periodicity of Ca2+ ions in the HAP crystal lattice also interfere with the adsorption of serum proteins (15,37).

Alternatively, Col I derived peptides DGEA, GFOGER, and P15 increase MSC attachment to hydroxyapatite and demonstrate greater osteogenesis in vivo compared to RGD (17,37). Col I derived peptide conformation, in addition to specificity towards non-RGD binding integrins, contribute to greater osteogenesis in vivo. Similarly, the phage-derived peptide DPI-VTK may exhibit non-RGD binding integrin specificity while selectively improving MSC adhesion strength towards hydroxyapatite. While other Col I derived peptides, such as P15, have been investigated in greater depth and have advanced to use in humans, they mimic known sequences in ECM molecules. The phage-derived peptide DPI-VTK contains non-obvious amino acid sequences in both the mineral and cell-binding domains and results in MSC-specific adhesion. Increased adhesion strength from binding specific MSC receptors can also increase mechanotransductive and/or osteogenic signaling cascades (38,39). For instance, Col I receptor binding leads to greater osteogenecity than RGD-integrin binding (40–42). Stronger RGD-integrin receptor binding as a result of co-delivery with fibronectin fragments also leads to greater osteogenecity. DPI may be demonstrating specificity to a combination of non-RGD integrins, which could be contributing to its increased adhesion strength to MSCs compared to fibroblasts and osteoblasts.

Although more cells initially bound RGD-VTK, there were more cells on DPI-VTK compared to RGD-VTK by day 7 (Fig. 6a). The increased cell proliferation on DPI-VTK could be attributed to the attachment of a more proliferative MSC subpopulation or through a peptide induced effect. Early expression of Runx2 and OSX followed by increased ALP expression indicate osteogenic differentiation of MSCs on DPI-VTK (Fig. 6b). Interestingly MSCs cultured on VTK exhibit elevated gene expression for differentiation markers ALP and OCN compared to apatite films. Taken together, DPI-VTK enhanced proliferation and differentiation of MSCs on mineralized substrates compared to uncoated substrates.

The data presented in this paper indicate that phage display can be used to identify hBMSC and material specific peptides that increase cell attachment, spreading, proliferation, and differentiation on biomaterial surfaces, which can drive improved regeneration in vivo.

Conclusion

DPIYALSWSGMA was discovered via phage display as a high MSC binding sequence. This peptide was combined with a mineral binding sequence, VTKHLNQISQSY, to form a modular, charge-neutral dual peptide capable of anchoring to a biomimetic surface and specifically recruit MSCs to the surface. The dual peptide DPI-VTK increased binding affinity to apatite compared to cell, mineral, and dual peptide controls. Moreover, DPI-VTK improved MSC attachment and specificity, and promoted cell spreading, proliferation and differentiation on apatite. These data demonstrate the utility of phage display to recruit specific cell populations to specific biomaterial substrates. The strategy of generating modular peptides for specific cell recruitment can broaden the existing strategies for bone tissue regeneration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Sergei Kuznetsov for the generous contribution of primary human bone marrow stromal cells and Dr. Paul Krebsbach for the induced pluripotent mesenchymal cells. Funded by NIH DE015411, R01 DE026116.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mankani MH, Kuznetsov SA, Wolfe RM, Marshall GW, Robey PG. In vivo bone formation by human bone marrow stromal cells: reconstruction of the mouse calvarium and mandible. Stem Cells. 2006 Sep;24(9):2140–9. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krebsbach PH, Kuznetsov SA, Satomura K, Emmons RV, Rowe DW, Robey PG. Bone formation in vivo: comparison of osteogenesis by transplanted mouse and human marrow stromal fibroblasts. Transplantation. 1997 Apr 27;63(8):1059–69. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199704270-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.LeBaron RG, Athanasiou KA. Tissue Eng. 2. Vol. 6. Laboratory of Extracellular Matrix and Cell Adhesion Research, Division of Life Sciences, The University of Texas at San Antonio; San Antonio, Texas, USA: 2000. Apr, Extracellular matrix cell adhesion peptides: functional applications in orthopedic materials; pp. 85–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Segvich S, Luong LNKD. Biomimetic Approaches to Synthesize Mineral and Mineral/Organic Biomaterials. In: Ahmed W, Ali NOA, editors. Biomaterials and Biomedical Engineering. 2008. pp. 327–78. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramaswamy J, Ramaraju S, Kohn DH. Bone-Like Mineral and Organically Modified Bone-Like Mineral Coatings. In: Zhang S, editor. Biological and Biomedical Coatings Handbook, Processing and Characterization. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2011. pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy WL, Kohn DH, Mooney DJ. Growth of continuous bonelike mineral within porous poly(lactide-co-glycolide) scaffolds in vitro. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;50:50–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(200004)50:1<50::aid-jbm8>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shekaran A, García AJ. Extracellular matrix-mimetic adhesive biomaterials for bone repair. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2011 Jan;96(1):261–72. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsiong SX, Boontheekul T, Huebsch N, Mooney DJ. Tissue Eng A. 2. Vol. 15. Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Ann Arbor; Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA: 2009. Feb, Cyclic arginine-glycine-aspartate peptides enhance three-dimensional stem cell osteogenic differentiation; pp. 263–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JS, Lee JS, Wagoner-Johnson A, Murphy WL. Modular peptide growth factors for substrate-mediated stem cell differentiation. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009 Jan;48(34):6266–9. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lutolf MP, Weber FE, Schmoekel HG, Schense JC, Kohler T, Muller R, et al. Nat Biotechnol. 5. Vol. 21. Institute for Biomedical Engineering, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Zurich and University of Zurich; Zurich, Switzerland: 2003. May, Repair of bone defects using synthetic mimetics of collagenous extracellular matrices; pp. 513–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Itoh D, Yoneda S, Kuroda S, Kondo H, Umezawa A, Ohya K, et al. Enhancement of osteogenesis on hydroxyapatite surface coated with synthetic peptide (EEEEEEEPRGDT) in vitro. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002 Nov;62(2):292–8. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kantlehner M, Schaffner P, Finsinger D, Meyer J, Jonczyk A, Diefenbach B, et al. Surface coating with cyclic RGD peptides stimulates osteoblast adhesion and proliferation as well as bone formation. Chembiochem. 2000 Aug 18;1(2):107–14. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20000818)1:2<107::AID-CBIC107>3.0.CO;2-4. Institut fur Organische Chemie und Biochemie Technische Universitat Munchen Lichtenbergstrasse 4, 85747 Garching Germany. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stayton PS, Drobny GP, Shaw WJ, Long JR, Gilbert M. Molecular Recognition At the Protein-Hydroxyapatite Interface. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003 Sep 1;14(5):370–6. doi: 10.1177/154411130301400507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilbert M, Shaw WJ, Long JR, Nelson K, Drobny GP, Giachelli CM, et al. Chimeric peptides of statherin and osteopontin that bind hydroxyapatite and mediate cell adhesion. J Biol Chem. 2000 May 26;275(21):16213–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001773200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hennessy KM, Clem WC, Phipps MC, Sawyer AA, Shaikh FM, Bellis SL. The effect of RGD peptides on osseointegration of hydroxyapatite biomaterials. Biomaterials. 2008 Jul;29(21):3075–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhatnagar RS, Qian JJ, Wedrychowska A, Sadeghi M, Wu YM, Smith N. Design of biomimetic habitats for tissue engineering with P-15, a synthetic peptide analogue of collagen. Tissue Eng. 1999 Feb;5(1):53–65. doi: 10.1089/ten.1999.5.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomar F, Orozco R, Villar JL, Arrizabalaga F. P-15 small peptide bone graft substitute in the treatment of non-unions and delayed union. A pilot clinical trial. Int Orthop. 2007 Feb;31(1):93–9. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0087-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Artzi Z, Kozlovsky A, Nemcovsky CE, Moses O, Tal H, Rohrer MD, et al. Histomorphometric evaluation of natural mineral combined with a synthetic cell-binding peptide (P-15) in critical-size defects in the rat calvaria. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2008 Jan;23(6):1063–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emam H, Beheiri G, Elsalanty M, Sharawy M. Microcomputed tomographic and histologic analysis of anorganic bone matrix coupled with cell-binding peptide suspended in sodium hyaluronate carrier after sinus augmentation: a clinical study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2011 Jan;26(3):561–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mobbs RJ, Maharaj M, Rao PJ. Clinical outcomes and fusion rates following anterior lumbar interbody fusion with bone graft substitute i-FACTOR, an anorganic bone matrix/P-15 composite. J Neurosurg Spine. 2014 Dec;21(6):867–76. doi: 10.3171/2014.9.SPINE131151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee JS, Wagoner Johnson AJ, Murphy WL. A modular, hydroxyapatite-binding version of vascular endothelial growth factor. Adv Mater. 2010 Dec 21;22(48):5494–8. doi: 10.1002/adma.201002970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujisawa R, Mizuno M, Nodasaka Y, Kuboki Y. Attachment of osteoblastic cells to hydroxyapatite crystals by a synthetic peptide (Glu7-Pro-Arg-Gly-Asp-Thr) containing two functional sequences of bone sialoprotein. Matrix Biol. 1997 Apr;16(1):21–8. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(97)90113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Addison WN, Miller SJ, Ramaswamy J, Mansouri A, Kohn DH, McKee MD. Phosphorylation-dependent mineral-type specificity for apatite-binding peptide sequences. Biomaterials. 2010 Dec;31(36):9422–30. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuznetsov SA, Mankani MH, Robey PG. In vivo formation of bone and haematopoietic territories by transplanted human bone marrow stromal cells generated in medium with and without osteogenic supplements. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2013 Mar;7(3):226–35. doi: 10.1002/term.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuznetsov Sa, Krebsbach PH, Satomura K, Kerr J, Riminucci M, Benayahu D, et al. Single-colony derived strains of human marrow stromal fibroblasts form bone after transplantation in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 1997 Sep;12(9):1335–47. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.9.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mandava S, Makowski L, Devarapalli S, Uzubell J, Rodi DJ. RELIC--a bioinformatics server for combinatorial peptide analysis and identification of protein-ligand interaction sites. Proteomics. 2004 May;4(5):1439–60. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Segvich SJ, Smith HC, Kohn DH. The adsorption of preferential binding peptides to apatite-based materials. Biomaterials. 2009;30:1287–98. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Makowski L, Soares A. Estimating the diversity of peptide populations from limited sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2003 Mar 1;19(4):483–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Young B, Pitt W, Cooper S. Protein adsorption on polymeric biomaterials I. Adsorption isotherms. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1988 Jul;124(1):28–43. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsai T, Mehta RC, Deluca PP. Adsorption of peptides to poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide): 1. Effect of physical factors on the adsorption. Int J Pharm. 1996 Jan;127(1):31–42. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meder F, Hintz H, Koehler Y, Schmidt MM, Treccani L, Dringen R, et al. Adsorption and orientation of the physiological extracellular peptide glutathione disulfide on surface functionalized colloidal alumina particles. J Am Chem Soc. 2013 Apr 24;135(16):6307–16. doi: 10.1021/ja401590c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia AJ, Gallant ND. Stick and grip: measurement systems and quantitative analyses of integrin-mediated cell adhesion strength. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2003;39(1):61–73. doi: 10.1385/CBB:39:1:61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McClay DR, Hertzler PL. Quantitative measurement of cell adhesion using centrifugal force. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. 2001 May;Chapter 9(Unit 9.2) doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb0902s00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villarreal-Ramirez E, Garduño-Juarez R, Gericke A, Boskey A. The role of phosphorylation in dentin phosphoprotein peptide absorption to hydroxyapatite surfaces: a molecular dynamics study. Connect Tissue Res. 2014 Aug;55(Suppl 1):134–7. doi: 10.3109/03008207.2014.923870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Addison WN, Masica DL, Gray JJ, McKee MD. Phosphorylation-dependent inhibition of mineralization by osteopontin ASARM peptides is regulated by PHEX cleavage. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:695–705. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luck K, Travé G. Phage display can select over-hydrophobic sequences that may impair prediction of natural domain-peptide interactions. Bioinformatics. 2011 Apr 1;27(7):899–902. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hennessy KM, Pollot BE, Clem WC, Phipps MC, Sawyer AA, Culpepper BK, et al. The effect of collagen I mimetic peptides on mesenchymal stem cell adhesion and differentiation, and on bone formation at hydroxyapatite surfaces. Biomaterials. 2009 Apr;30(10):1898–909. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.12.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eyckmans J, Boudou T, Yu X, Chen CS. A hitchhiker’s guide to mechanobiology. Dev Cell. 2011 Jul 19;21(1):35–47. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ingber DE. Cellular mechanotransduction: putting all the pieces together again. FASEB J. 2006 May;20(7):811–27. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5424rev. Vascular Biology Program, Karp Family Research Laboratories 11.127, Department of Pathology, Harvard Medical School and Children’s Hospital, 300 Longwood Ave., Boston, Massachusetts 02115, USA donald.ingber@childrens.harvard.edu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.García AJ, Schwarzbauer JE, Boettiger D. Distinct activation states of α5β1 integrin show differential binding to RGD and synergy domains of fibronectin. Biochemistry. 2002;41(29):9063–9. doi: 10.1021/bi025752f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petrie Ta, Capadona JR, Reyes CD, García AJ. Integrin specificity and enhanced cellular activities associated with surfaces presenting a recombinant fibronectin fragment compared to RGD supports. Biomaterials. 2006;27(31):5459–70. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feng Y, Mrksich M. The synergy peptide PHSRN and the adhesion peptide RGD mediate cell adhesion through a common mechanism. Biochemistry. 2004;43(50):15811–21. doi: 10.1021/bi049174+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.