Abstract

Objectives

Late contrast enhancement CT (LCE-CT) visualizes the presence of myocardial infarcts. Differentiation of the contrast-enhanced infarct from blood pool is challenging. We developed a novel method using data from first pass CT angiography (CTA) imaging to enable automatic infarct detection.

Materials and Methods

A canine model of myocardial infarction was produced in 11 animals. Two months later, first pass CTA (90 kVp) and LCE-CT (dual energy 90 kVp/150 kVp tin filtered) were performed. Late gadolinium enhancement MRI was used as reference standard. The CTA and LCE-CT were co-registered using a fully automatic non-rigid method based on curved B-splines. The method allowed for limited elastic deformation and the considerable differences in attenuation between first-pass and delayed image. The blood pool was easily identified on the CTA image by high attenuation. Because CTA and LCE-CT were registered, the blood pool segmentation can be directly transferred to the LCE-CT – thereby solving the key problem of infarct/blood pool differentiation. The remaining segmentation of infarcted vs. noninfarcted myocardium was performed using a threshold. Automatic and MRI-guided expert segmentations of LCE-CT infarcts were compared to each other on volume and area basis (intraclass correlation coefficient, ICC) and on voxel basis (dice similarity coefficient, DSC between automatic and expert CT segmentation). CT infarct volumes were compared with the reference standard MRI.

Results

The infarcts were mainly subendocardial (81 %) and relatively small (median MRI infarct mass 7.4 gram). The automatic segmentation showed excellent agreement with expert segmentation on volume and area measurements (ICC = 0.96 and 0.87, respectively). DSC showed moderately good agreement (DSC =0.47). Compared to MRI there was modest agreement (ICC = 0.62) and excellent correlation (R=0.9). Manual interaction was less than 1 minute per exam.

Conclusion

We propose an automatic method for infarct segmentation on LCE-CT using multiphase CT information, which showed excellent agreement with expert readers and favorable correlation with MRI.

Keywords: Myocardial Infarct, delayed iodine contrast, late contrast enhancement CT

Introduction

Imaging of myocardial scar and infarction using late gadolinium enhancement MRI (LGE-MRI) is routinely performed and provides valuable information for patient management. 1 In an analogous fashion, CT imaging of late iodine contrast enhancement (LCE-CT) could potentially be used for infarct detection. 2,3 Coronary CT angiography in the setting of coronary artery disease is frequently used in clinical medicine but lacks myocardial tissue characterization. In some patients, the ability to image myocardial infarct and scar would be highly attractive, especially if it could be performed in the same session and without additional contrast application.

In comparison to LGE-MRI, the contrast to noise ratio for late contrast enhancement CT is much lower (by 50% or more 4). Compared with single-energy CT, dual-energy CT can improve CNR to some extent. 5, 6 To maximize infarct conspicuity, late contrast enhancement CT is performed after intravenous administration of 40-50 g iodine. High iodine loads improve the contrast to noise ratio of the enhancing infarct compared to normal myocardium. Unfortunately, high iodine loads also result in relatively high attenuation of the blood pool. Thus in practice, it is frequently difficult to differentiate between infarct and blood pool, especially in the setting of non-transmural infarction. This phenomenon – although clinically less prominent - has also been described for MRI imaging. 4

To solve the problem of infarct versus blood pool segmentation, we propose that the key information – the blood pool contours – can be retrieved from the CT angiography acquisition. However, due to differences in breathing and cardiac cycle, the CT angiography and late iodine enhancement CT acquisitions are not aligned and not necessarily at the same cardiac phase. For detection of infarcts, misalignment of a few millimeters already leads to erroneous infarct delineation.

This problem can be addressed with image co-registration, a key technology in medical imaging which has made significant progress in recent years (reviewed in 7). The basic idea is to automatically find the corresponding locations in a pair of images - in our study between the CTA and the LCE-CT - and to transform the CTA image in a way that each voxel of the transformed CTA is aligned with the anatomically corresponding voxel in the LCE-CT. There are several moving components involved (heart, lung and rib cage) and therefore a simple rotation or translation will likely not fully reconcile two separate acquisitions. Methods that are “non-rigid” allow for local deformation to align the two images and enable coregistration of typical chest CT images. The additional challenge of largely different attenuation values between CTA and LCE-CT in this study can also be overcome with modern image processing algorithms.

In this work, we investigate a method of advanced non-rigid co-registration to align the CTA and the late contrast enhancement CT. We then extract the blood pool information from the CTA and use this information to segment the blood pool on LCE-CT, thus facilitating automated segmentation of infarcts. For validation, we compare the proposed automatic infarct segmentation to a manual and MRI supported expert segmentation and to volumetric results obtained using LGE-MRI.

Materials and Methods

Animal Model

All experiments were approved by our institution's animal care and use committee and were performed in accordance with animal care regulations. Continuous care by a veterinarian team was provided. In adult male mongrel dogs, a myocardial infarction was induced by vascular clamp occlusion of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery for 90 minutes followed by reperfusion. 8, 9 Imaging was performed at 6-8 weeks. All animals were anesthetized, intubated and ventilated in preparation for imaging studies. Propofol IV was given to allow intubation and anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane (0.5-2.5%) and oxygen (2 liters/min flow).

Image Acquisition

A dual source dual-energy capable scanner was used (SOMATOM Force, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). A test bolus was used for timing of the first pass CT angiography. A retrospectively ECG-gated spiral acquisition was performed with a tube voltage of 90 kVp at first pass. For delayed imaging, a retrospectively ECG-gated spiral dual energy acquisition with tube voltages of 90/150kVpSN (150kv with tin filter applied) was performed and tube currents are listed in table 1. Images were reconstructed at 75% of the R-R interval. The rotation time was 250 msec. Delayed images were acquired 12 minutes after application of 1.5 ml/kg body weight of contrast (iopamidol, Isovue 370 Bracco, Singen, Germany). Up to 15 mg of metoprolol were used for heart rate control.

Table 1. Animal characteristics and CT scan parameters.

| Parameter | Median [IQR] N=11 |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 1.30 [1.14;1.38] |

| Sex: M | 11 (100%) |

| Weight (kg) | 28.0 [27.2;29.2] |

| Heart Rate (/min) | 93.0 [88.5;101] |

| LV.EF (%) | 34.0 [26.5;43.5] |

| Infarct Mass (g) | 7.4 [5.4;8.1] |

| Infarct Transmural | 1 (9%) |

| mAs/rot 90kVp | 179 [179;179] |

| mAs/rot 150kVp | 138 [138;138] |

| Dose (mSv) | 5.49 [4.95;6.35] |

| DLP (mGycm) | 392 [354;454] |

| CTDIvol (mGy) | 24.6 [22.6;25.9] |

Images were reconstructed using Br36 (medium sharp soft tissue) kernel and Qr36 (medium sharp quantitative) kernel in CTA and late enhancement imaging, respectively. Iterative reconstruction was used (ADMIRE 4). The slice thickness was 0.5 mm. For late contrast enhancement acquisitions we created monoenergetic reconstructions at 70 keV using a noise optimized algorithm (Syngo.via, Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany, software setting “Mono+”). We chose a 70 keV reconstruction because absolute image noise is usually lowest in this range 10.

MRI was performed with late gadolinium enhancement (25 minutes after application of 0.2 mmol/kg Gd-DOTA meglumine) using a 3T MRI scanner (Biograph MR, Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany). “TI scout” images were used to optimize inversion times for suppression of normal myocardium. For 3D late gadolinium imaging a T1-weighted inversion recovery 3D gradient echo imaging sequence was used (TR/TE, 20/3.2 ms; flip angle, 15°, 1 mm slice thickness with no gap, 1×1×1 pixel size). In addition, 2D short axis LGE images were obtained using an inversion recovery prepared gradient echo sequence with slice thickness of 6 mm and gap 1-2 mm.

Image processing

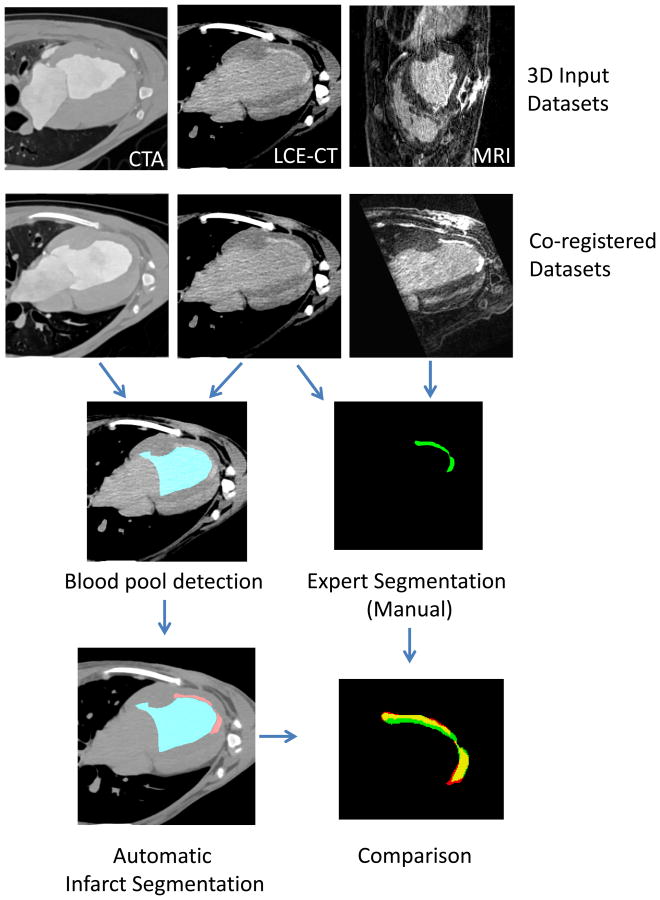

Figure 1 provides an overview of the image processing steps. We used the Python programming language (version 2.7.12, Python Software Foundation) with numpy, scipy and Elastix 11 for image processing. Images were resized to a voxel size of 0.25 mm (isovolumetric). Co-registration of CTA and LCE-CT was performed using the software Elastix. The detailed parameters are listed in the supplemental information. The parameters were selected empirically based on the coregistration of one preselected scan. After co-registration, images were resampled to 0.5 mm isotropic resolution.

Figure 1.

The CTA, late contrast enhancement CT (LCE-CT) and MRI 3D images were coregistered. The proposed algorithm uses the CTA and delayed iodine CT information. The CTA image facilitates the blood pool detection (blue) and using this information the LCE-CT image is used for infarct segmentation (lower left image, red). The expert had the MRI and LCE-CT images and the pathology results available to perform the manual segmentation (green). Automatic CT segmentation was compared with expert MRI-enhanced segmentation.

The key issue was to achieve a non-rigid registration using curved B-splines but to ensure suppression of extreme distortions, which could lead to erroneous over-registration at the infarct locations. This can be achieved by penalizing extreme distortions (bending energy penalty term 12).

The approach to align the CTA and LCE-CT on absolute HU voxel values would fail because of large differences in attenuation due to high arterial contrast concentration in the CTA. Instead of trying to reconcile the two images to match absolute HU values it is possible to align the images to achieve optimal relative similarity (maximum mutual information 7).

On the CTA image, the blood pool was detected using a threshold of 220 (shown on figure 1) and selecting the largest connected object. The blood pool includes left atrial and left ventricular lumen. The only manual interaction was removal of the atrial portion of the blood pool by drawing a line at the mitral valve plane (time effort < 1 min). Infarct voxels were detected based on two criteria: 1) Attenuation is higher than an adaptive threshold and 2) distance to the blood pool is less than 7 mm (excluding blood pool itself). This ensures that all detected voxels are within the myocardium.

The threshold for infarct detection was calculated as follows. Because the normal myocardium contains both extracellular matrix and capillary blood vessels, the attenuation of myocardium is correlated with the blood pool attenuation. 13 Therefore we used an adaptive threshold for normal myocardium based on a linear equation with a = 28 and b = 0.32 (empirical):

We compared the infarct detection on late contrast enhancement CT using the automatic algorithm versus manual expert segmentation where the expert had additional access to LGE MRI data and pathology results as a standard of reference. To facilitate the manual segmentation we co-registered the late contrast enhancement CT and the 3D LGE MRI using manual, rigid landmark based manual co-registration (3d Slicer, https://www.slicer.org/14). While viewing the CT and MRI images side-by-side, an expert (VS, cardiologist, 6 years of experience in cardiovascular imaging) generated a voxel-wise segmentation of the infarcted area. This enabled us to perform comparisons on the exam level (infarct volume), on the slice level (infarct area per slice) and on the voxel level (dice similarity coefficient, DSC). All steps were performed using freely available open-source software.

MRI Infarct size measurement

We used QMass MR (Version 8.1, Medis, Leiden, Netherlands) for MRI infarct size measurement. The endocardial and epicardial borders were traced manually. The infarct size measurement was then performed automatically by the software without any additional manual adjustments. To achieve comparable slice thickness between CT and MRI we resampled the CT infarct segmentation to 8 mm slice thickness (the 2D MRI slice thickness plus gap was 7-8 mm).

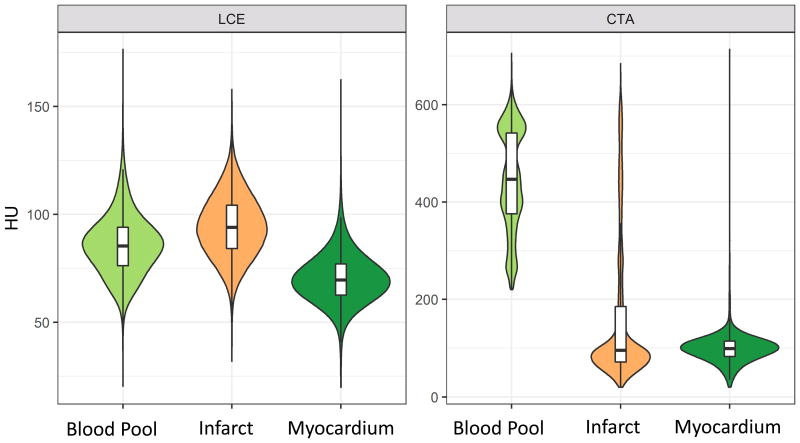

Attenuation Distribution Plots

Based on expert segmentations and automatic LV segmentations voxel HU values were extracted each region (infarct, non-infarcted myocardium, blood pool). Approx. 9 million voxels were evaluated. Histograms were generated using R.

Statistical analysis

R (Version 3.2.1, https://www.r-project.org/) was used for statistical analysis. Measurements are reported as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range. A p-value <0.05 was considered significant. Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) with confidence interval and Bland-Altman analysis was used for volume and area comparison. The following categories for ICC were used: excellent for ICC >0.75, good for ICC >0.6 and ≤0.75, fair for ICC >0.4 and ≤0.6 and poor for ICC≤0.4. 15 For voxel-based agreement the dice similarity coefficient (DSC) between two segmentations A and B was evaluated. The DSC is a spatial overlap metric and was calculated as shown below 16.

Result

The animal characteristics and CT scan parameters are shown in table 1. The median size of the infarcts was 7.4 grams and most were non-transmural (81%). As a result of the infarct generation the ejection fraction was moderately reduced, as expected. The heart rate during imaging was 93/min despite medical heart rate control, which was above the predefined optimal target heart rate (80/min).

Hounsfield Unit distribution

The HU distribution of the blood pool, myocardium, and infarct in the late contrast enhancement and CTA images are plotted in figure 2. In the LCE images there is significant overlap between blood pool (light green, mean attenuation 85.6 ±14.2 HU) and infarct (orange, mean attenuation 94.3 ± 14.6). The overlap of blood pool and infarct tissue precludes reliable differentiation of the infarct border compared to the blood pool based on threshold alone (contrast to noise ratio (CNR) = 0.62). In the CTA images there is a clear separation between blood pool and myocardium (infarcted and noninfarcted) which enables automatic differentiation using a threshold.

Figure 2.

Attenuation HU values were collected for each voxel in the blood pool (light green), myocardium (dark green) and infarct (orange) in all scans. The left panel shows the results for the late contrast enhancement. There is a significant overlap of HU between blood pool and infarct, precluding reliable separation. The left panel shows the results for the CTA images. Here the blood pool clearly shows much higher enhancement, which enables automatic differentiation between blood pool and infarcted and noninfarcted myocardium.

Infarct Segmentation Agreement

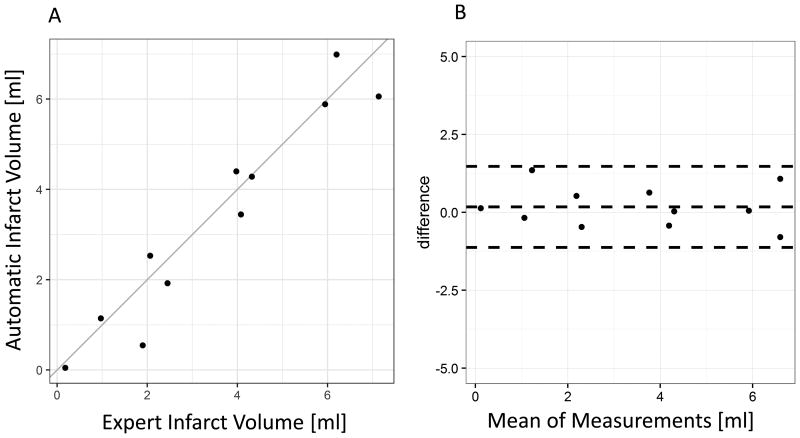

Infarct Volume

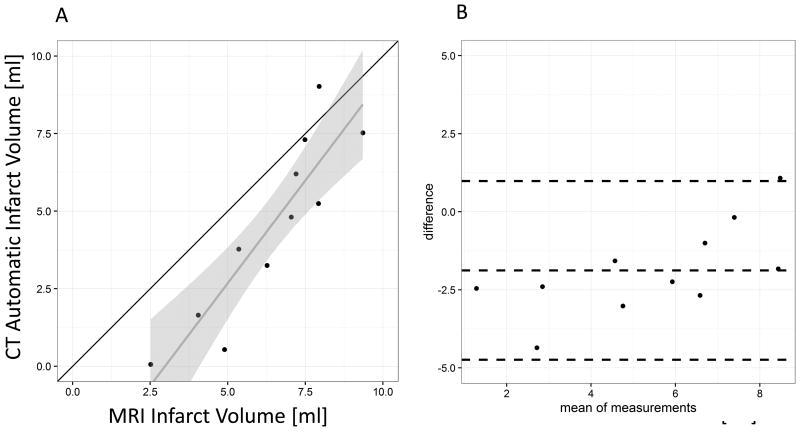

A comparison of infarct volumes measured by dual phase CT automatic segmentation vs. expert/MRI-guided segmentation is shown in figure 3 (scatterplot and Bland-Altman plot). There was an excellent correlation of the volume measurements (ICC = 0.959, CI 0.864 – 0.989, Bland-Altman limits of agreement 1.48, -1.12 and bias 0.178 ml).

Figure 3.

A: Comparison of expert segmentation infarct volume with automatic infarct volume shows excellent agreement with an Intraclass Correlation Coefficient ICC = 0.959. B: Bland Altman analysis shows low bias (center line, 0.178 ml). The upper and lower lines show the ± 1.96 SD range.

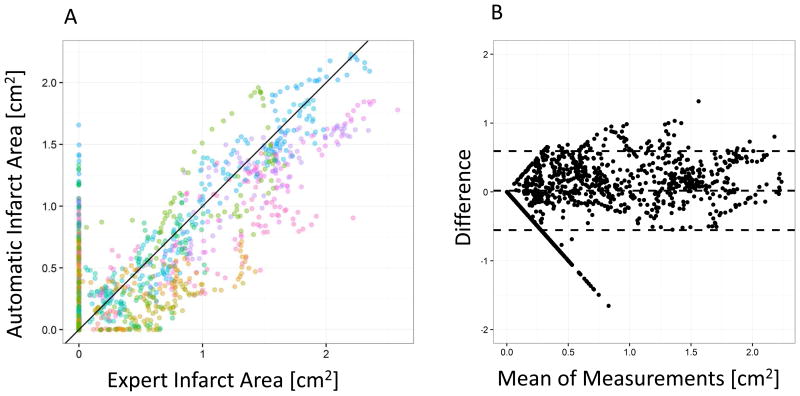

Per Slice Infarct Area

Due to the fully registered nature of our dataset, we can compare agreement on a local basis, e.g. per slice. A comparison of per slice infarct areas measured by dual phase CT automatic segmentation vs. expert/MRI-guided segmentation is shown in figure 4 (scatterplot and Bland-Altman plot). The method agreement was slightly lower compared with the total volume assessment but ICC was still excellent (ICC = 0.868, CI 00.857 – 0.878, Bland-Altman limits of agreement 0.59, -0.55 and bias 0.019 cm2).

Figure 4.

A: Comparison of per slice expert segmentation infarct area with automatic infarct volume shows excellent agreement with an Intraclass Correlation Coefficient ICC = 0.868. Each color denotes an individual exam. B: Bland Altman analysis shows low bias (center line, 0.019 ml).

Voxel-based Segmentation

For assessment of segmentation quality on the voxel level, we used the dice similarity coefficient (DSC). The coefficient ranges from 0 (no similarity) to 1 (identity). The dice coefficient for the per voxel infarct segmentation was 0.467 ± 0.14 indicating reasonably good agreement (0.4 – 0.75 is considered good agreement 17). Examples of automatic and expert segmentations are shown in figure 5.

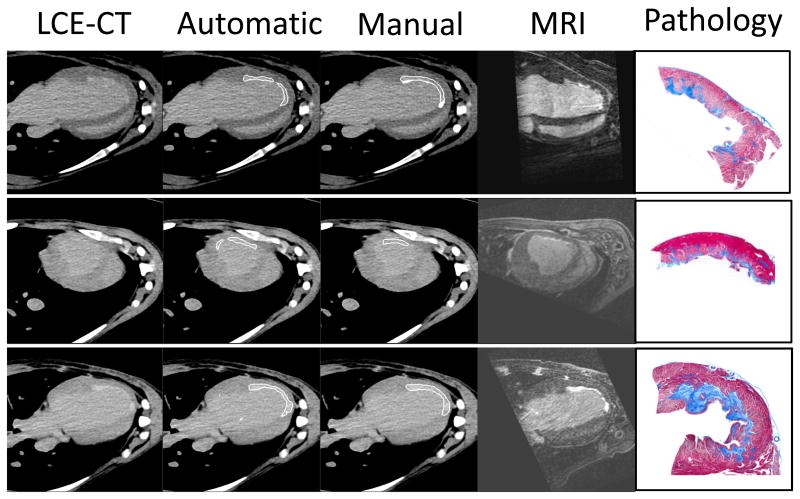

Figure 5.

Examples of base images (late contrast enhancement CT – LCE), automatic and manual segmentations are shown. On the right side, the corresponding delayed gadolinium MRI and representative pathology images are shown (Masson's trichrome stain, greyscale images show the infarcted area as dark grey).

Comparison with MRI infarct volumes

The clinical standard of reference for noninvasive infarct imaging is 2D late gadolinium enhancement MRI. We obtained 2D MRI images and used a standard software package to measure infarct area. We compared fully automatic CT infarct segmentation volumes to the MRI reference standard. Figure 6 shows a scatterplot and a Bland-Altman plot of the MRI and CT infarct volumes. There was an excellent correlation of the measurements (R=0.896) but there was evidence that infarct volumes in the CT measurements were underestimated compared to the MRI, especially in small infarcts (see figure 5 B, Bland-Altman Plot). As a consequence the ICC indicated fair to good agreement (ICC = 0.618). This was equally evident in the expert segmentations (for comparison see supplemental figure 1).

Figure 6.

Comparison between CT automatic infarct volume measurements and 2D MRI standard measurements. A: Scatterplot with identity line (black) and linear regression line (grey, confidence interval light grey). B: Bland Altman plot. In summary, there is excellent correlation but only modest agreement due to underestimation of infarct sizes by CT, especially in small infarcts.

Discussion

In the setting of suspected coronary artery disease, CT angiography in combination with late enhancement CT promises a fast and attractive combined assessment of vascular and myocardial pathology. Challenges for LCE-CT are low iodine contrast of infarcts and limited separation of infarct from blood pool.

We hypothesized that automatic segmentation of infarcts on LCE-CT images is feasible despite these limitations by using multi-phase information combining and co-registering CTA and LCE-CT. This proposed multi-phase segmentation algorithm compared favorably with a human expert segmentation and with the clinical reference standard LGE MRI.

Iodine contrast provides much lower signal in late contrast enhancement CT compared with Gadolinium in MRI. Due to higher signal of gadolinium contrast and lower noise levels automatic segmentation of infarcts was shown to be feasible in delayed enhancement MRI 18, 19 although visual assessment is frequently used. Using improved image reconstructions and dual energy CT, the signal to noise ratio can be increased 5, 20-22 but infarct imaging using CT remains technically challenging. Using dual energy CT, Wichmann et al. 5 report CNR between myocardium and infarct of (74.6/26.7 = ∼3) but the CNR between infarct and blood pool even with optimized dual energy CT was only about (33.2/29.6 = 1.2). We recently showed that advanced post-processing can further improve CNR of infarct vs. normal myocardium to ∼ 4.2, 22 but the issue of limited separation between infarct and blood pool remains problematic. Thus, spectral CT by itself is unlikely to be sufficient for CT identification of infarct and thus late contrast enhancement CT scans requires new solutions for automatic segmentation. The histograms in figure 2 further emphasize this issue with a large overlap of the HU histograms of infarct and myocardium (contrast to noise ratio < 1).

Our study showed that using co-registered multiphase high-resolution CT information it is possible to perform automatic segmentation of delayed contrast CT data with excellent agreement compared with a manual and MRI supported expert segmentations (ICC > 0.87 for volume and per slice area). We also compared our automatic CT method to 2D LGE MRI, the clinical standard of reference for noninvasive infarct imaging. While there was excellent correlation there was evidence of underestimation of infarct size by CT. In this context it should be mentioned that the infarcts in this study were small in size (on average 7 grams of tissue), while in a clinical patient study 23 the median infarct size was 20 grams. We speculate that due to lower signal to noise ratio of CT compared with MRI the CT infarct signal may be lost in the noise floor in the border areas of small infarcts.

In addition it should be noted that we used thin slice reconstructions because this provides detailed and near isovolumetric 3D information for the automatic coregistration process. On the other hand these reconstructions have inherently higher noise compared with commonly used thick slices. We didn't explore alternative slice thickness settings or other reconstruction kernels in conjunction with the proposed method; therefore we cannot determine the optimal reconstruction settings. Further validation of the algorithm in human clinical CT scans would provide additional insights.

There are several limitations of this study. First, we used a canine model that provided the opportunity for high-quality CT images performed on the same day as the MRI acquisition and the pathologic information on infarct presence, but applicability to human studies remains untested. All of the infarcts analyzed were in the LAD territory due to the animal model that was used. While there was considerable heterogeneity in infarct size, the infarct location was similar in all animals. The scars examined in this study were all subendocardial; therefore this method may perform differently in mid-myocardial and sub-epicardial scars. A non-rigid coregistration algorithm carries the risk of misregistration in the infarct area due to similar HU of infarct and blood pool. We aimed to keep this effect to a minimum by using a semi-rigid method.

Conclusions

In summary, automatic detection of infarcts on late contrast enhancement CT (LCE-CT) images is feasible by combining LCE-CT with blood pool information from the CTA acquisition. This technique allows fast automated extraction of infarct size in an observer independent manner that compares favorably with expert segmentations and MRI results.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Funding was provided by the NIH intramural research program (no specific grant number available).

Footnotes

No conflicts of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bruder O, Schneider S, Nothnagel D, Dill T, Hombach V, Schulz-Menger J, Nagel E, Lombardi M, van Rossum AC, Wagner A, Schwitter J, Senges J, Sabin GV, Sechtem U, Mahrholdt H. EuroCMR (European Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance) registry: results of the German pilot phase. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1457–1466. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurobe Y, Kitagawa K, Ito T, Kurita Y, Shiraishi Y, Nakamori S, Nakajima H, Nagata M, Ishida M, Dohi K, Ito M, Sakuma H. Myocardial delayed enhancement with dual-source CT: advantages of targeted spatial frequency filtration and image averaging over half-scan reconstruction. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2014;8:289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerber BL, Belge B, Legros GJ, Lim P, Poncelet A, Pasquet A, Gisellu G, Coche E, Vanoverschelde JL. Characterization of acute and chronic myocardial infarcts by multidetector computed tomography: comparison with contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance. Circulation. 2006;113:823–833. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.529511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim YK, Park EA, Lee W, Kim SY, Chung JW. Late gadolinium enhancement magnetic resonance imaging for the assessment of myocardial infarction: comparison of image quality between single and double doses of contrast agents. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;30(Suppl 2):129–135. doi: 10.1007/s10554-014-0505-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wichmann JL, Hu X, Kerl JM, Schulz B, Bodelle B, Frellesen C, Lehnert T, Vogl TJ, Bauer RW. Nonlinear blending of dual-energy CT data improves depiction of late iodine enhancement in chronic myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;30:1145–1150. doi: 10.1007/s10554-014-0440-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandfort V, Palanisamy S, Symons R, Pourmorteza A, Ahlman MA, Rice K, Thomas T, Davies-Venn C, Krauss B, Kwan A, Pandey A, Zimmerman SL, Bluemke DA. Optimized energy of spectral CT for infarct imaging: Experimental validation with human validation. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crum WR, Hartkens T, Hill DL. Non-rigid image registration: theory and practice. Br J Radiol. 2004;77 Spec No 2:S140–153. doi: 10.1259/bjr/25329214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nie SP, Wang X, Qiao SB, Zeng QT, Jiang JQ, Liu XQ, Zhu XM, Cao GX, Ma CS. Improved myocardial perfusion and cardiac function by controlled-release basic fibroblast growth factor using fibrin glue in a canine infarct model. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2010;11:895–904. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1000302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou D, Xiong L, Wu Q, Guo R, Zhou Z, Zhu Q, Jiang Y, Huang J. Effects of transmyocardial jet revascularization with chitosan hydrogel on channel patency and angiogenesis in canine infarcted hearts. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2013;101:567–574. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grant KL, Flohr TG, Krauss B, Sedlmair M, Thomas C, Schmidt B. Assessment of an advanced image-based technique to calculate virtual monoenergetic computed tomographic images from a dual-energy examination to improve contrast-to-noise ratio in examinations using iodinated contrast media. Invest Radiol. 2014;49:586–592. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein S, Staring M, Murphy K, Viergever MA, Pluim JP. elastix: a toolbox for intensity-based medical image registration. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2010;29:196–205. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2009.2035616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rueckert D, Sonoda LI, Hayes C, Hill DLG, Leach MO, Hawkes DJ. Nonrigid registration using free-form deformations: application to breast MR images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1999;18:712–721. doi: 10.1109/42.796284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nacif MS, Kawel N, Lee JJ, Chen X, Yao J, Zavodni A, Sibley CT, Lima JA, Liu S, Bluemke DA. Interstitial myocardial fibrosis assessed as extracellular volume fraction with low-radiation-dose cardiac CT. Radiology. 2012;264:876–883. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12112458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fedorov A, Beichel R, Kalpathy-Cramer J, Finet J, Fillion-Robin JC, Pujol S, Bauer C, Jennings D, Fennessy F, Sonka M, Buatti J, Aylward S, Miller JV, Pieper S, Kikinis R. 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;30:1323–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hallgren KA. Computing Inter-Rater Reliability for Observational Data: An Overview and Tutorial. Tutorials in quantitative methods for psychology. 2012;8:23–34. doi: 10.20982/tqmp.08.1.p023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egghe L. Good properties of similarity measures and their complementarity. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol. 2010;61:2151–2160. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tacher V, Lin M, Chao M, Gjesteby L, Bhagat N, Mahammedi A, Ardon R, Mory B, Geschwind JF. Semi-automatic volumetric tumor segmentation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Comparison between C-arm Cone Beam Computed Tomography and MRI. Academic Radiology. 2013;20:446–452. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu Y, Yang Y, Connelly KA, Wright GA, Radau PE. Automated quantification of myocardial infarction using graph cuts on contrast delayed enhanced magnetic resonance images. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2012;2:81–86. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4292.2012.05.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tufvesson J, Carlsson M, Aletras AH, Engblom H, Deux J-F, Koul S, Sörensson P, Pernow J, Atar D, Erlinge D, Arheden H, Heiberg E. Automatic segmentation of myocardium at risk from contrast enhanced SSFP CMR: validation against expert readers and SPECT. BMC medical imaging. 2016;16:19. doi: 10.1186/s12880-016-0124-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Srichai MB, Chandarana H, Donnino R, Lim II, Leidecker C, Babb J, Jacobs JE. Diagnostic accuracy of cardiac computed tomography angiography for myocardial infarction. World J Radiol. 2013;5:295–303. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v5.i8.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang LJ, Peng J, Wu SY, Yeh BM, Zhou CS, Lu GM. Dual source dual-energy computed tomography of acute myocardial infarction: correlation with histopathologic findings in a canine model. Invest Radiol. 2010;45:290–297. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181dfda60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandfort V, Palanisamy S, Symons R, Pourmorteza A, Ahlman MA, Rice K, Thomas T, Davies-Venn C, Krauss B, Kwan A, Pandey A, Zimmerman SL, Bluemke DA. Optimized energy of spectral CT for infarct imaging: Experimental validation with human validation. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alexandre J, Saloux E, Dugué AE, Lebon A, Lemaitre A, Roule V, Labombarda F, Provost N, Gomes S, Scanu P, Milliez P. Scar extent evaluated by late gadolinium enhancement CMR: a powerful predictor of long term appropriate ICD therapy in patients with coronary artery disease. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2013;15:12–12. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-15-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.