Abstract

Background

Chinese rural communities living among species-rich forests have little documentation on species used to make handicrafts and construction materials originating from the surrounding vegetation. Our research aimed at recording minor wood uses in the Heihe valley in the Qinling mountains.

Methods

We carried out 37 semi-structured interviews in seven villages.

Results

We documented the use of 84 species of plants. All local large canopy trees are used for some purpose. Smaller trees and shrubs which are particularly hard are selectively cut. The bark of a few species was used to make shoes, hats, steamers and ropes, but this tradition is nearly gone. A few species, mainly bamboo, are used for basket making, and year-old willow branches are used for brushing off the chaff during wheat winnowing.

Conclusions

The traditional use of wood materials documented suggests that some rare and endangered tree species may have been selectively cut due to their valuable wood, e.g. Fraxinus mandshurica and Taxus wallichiana var. chinensis. Some other rare species, e.g. Dipteronia sinensis, are little used and little valued.

Keywords: Minor timber forest products, Non-timber forest products, Taibai

Background

Construction wood and firewood are the main products of modern forestry. However local communities living in woodlands usually implement multiple uses of the forest, also involving the production of utensils, medicine and food. The importance of minor timber forest products and non-timber forest products (NTFP) has been emphasized for decades in ethnobotany, forestry, rural development etc. Some of these products may have a vital non-commercial value,others enter the cash economy and improve livelihoods [1–6]. Ethnobotanical works, however, often overlook the lesser-used types of wood available to local populations, emphasizing only the “non-timber” part of the ecosystem. The minor uses of wood are more closely documented in older ethnographic works. e.g. describing and documenting traditional tools and handicrafts, although the topic has also been touched upon by ethnobotany [7–14].

Chinese ethnobotany has been developing fast in recent years. However most papers are focused on traditional wild food and medicine, mainly among ethnic minorities. Although some papers are devoted to the issue of non-timber forest products in China [15–19], we observed a lack of studies concerning the ethnobotany of traditional handicrafts and other objects made of wood. In order to fill this gap we carried out a study in the Heihe National Forest Park in the Taibai range, Shaanxi province, China. Mount Taibai, the highest of the Qinling Mountains, is one of the most species-rich and valuable parts of nature in northern China. This area has preserved a rich woodland flora and fauna, which is well-studied. An area with a rich and well-documented flora is an ideal working place for an ethnobotanist. Over the past few years some of the authors of this paper have devoted a few articles to the use of wild food plants in one of the valleys of the Taibai range, and the use and cultivation of the highly toxic Aconitum carmichaelii [20–22].

Our research aimed to document minor wood uses in the Heihe valley. By this we mean any uses of wood, twigs or branches of trees, shrubs, climbers and bamboo apart from large scale construction wood or firewood. Both past uses (before the area became a national forest park) and present uses were recorded.

Methods

Study area

The study covers the Heihe National Forest Park (Fig. 1), on the southern side of the Taibai Nature Reserve, with the highest peak of northern China in the center of the reserve (Mt Taibai 3767 m a.s.l.). The nature reserve protects a highly diverse flora – from warm temperate (with subtropical elements), to alpine at the top. The National Forest Park (with a less strict protection regime) is adjacent to it, and mainly protects species-rich forests. The area is almost completely covered by ancient forest vegetation and rocky outcrops. The Heihe river valley belongs to the Houzhenzi administrative unit (town, zhen (镇)), with an area of 822 km2. It is a very isolated place, which has vehicular access to the county town of Zhouzhi (where the post-office and schools are located) only via a 2.5 h drive through a winding precipitous gorge, sometimes blocked for days by falling rocks. The whole valley is inhabited by 2813 people [23] – a quarter of them in the main settlement of Houzhenzi, and the rest in hamlets scattered throughout the forest (Fig. 1).

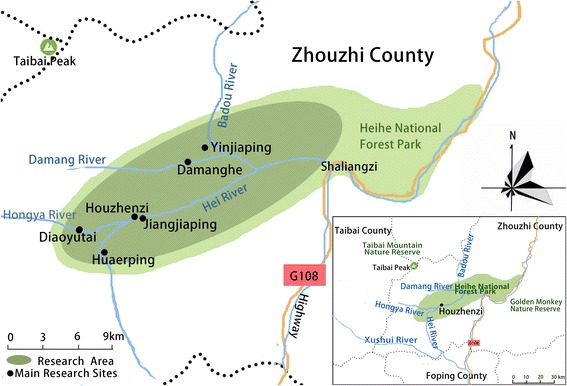

Fig. 1.

The location of the study

The studied villages lie between 1000 and 1500 m a.s.l. At these altitudes the climate is temperate, with daily temperatures in summer oscillating around 20–30 °C and winter temperatures around 10 °C to – 10 °C. The mean annual temperature in Houzhenzi is 8.2 °C, with a high rainfall of nearly 1000 mm, 44% of which is concentrated in the summer months. The dominant vegetation is the species-rich Quercus variabilis and Q. aliena var. acuteserrata forest, with an admixture of Pinus tabuliformis, and many deciduous tree species (e.g. Acer spp., Tilia spp.).

The majority of the local population are subsistence Han Chinese farmers who grow maize, potatoes, wheat and beans. Sources of cash income are the orchards of zaopi (Cornus officinalis), walnuts (Juglans regia) and northern Sichuan pepper (Zanthoxylum bungeanum). Digging out medicinal roots and collecting medicinal herbs for wholesale buyers is also a very popular activity. The importance of tourism is increasing. A significant proportion of farms are registered as agritourist farms (nong jia le). Most tourists come from Xian and its surroundings and are attracted by the beautiful scenery and hiking opportunities.

Data collection

The field research was conducted in the summer and autumn of 2016 using the Rapid Rural Appraisal approach [24, 25], and included 37 freelisting interviews in seven villages (Fig. 1), which involved 52 people altogether. This included 39 men and 13 women as the former were more willing to talk about this topic. The mean age of the participants was 55 (aged from 39 to 87).

The research was carried out following the code of ethics of the American Anthropological Association [26] and the International Society of Ethnobiology Code of Ethics [27]. Oral prior informed consent was acquired. The interviews were carried out in front of the dwellings of the interviewees in order to provide easy access to the tools and structures mentioned by the respondents. We asked the interviewees to list all the uses of wood, twigs or bark to make structures, tools and other objects in their own households and farms. This was the only question asked and at the beginning of the interviews no props were provided. At the end of each interview we asked to see the tools present in the yard, and sometimes more tree species were then mentioned (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 and 23). Additionally, discussion groups were organized to cross-check the identification of specimens. The listed taxa (Tables 1, 2 and 3) were identified using specimens collected by informants in the forest or in the village. The interviews were carried out in Mandarin Chinese, which is the first language of the local population.

Fig. 2.

A narrow hoe (juetou 镢头) resembling a pick-axe is a common agricultural tool, very useful in stoney mountain soil. The handle was made from a Cornus kousa branch

Fig. 3.

A sickle on a long handle (liandao, 镰刀, this one made of Cornus kousa) is another indispensable tool in the area

Fig. 4.

Two spade handles – the one on the left made from Meliosma wood, the one on the right from C. kousa

Fig. 5.

A barrel made of Catalpa wood

Fig. 6.

The commonest type of basket made of Phyllostachys bamboo. The handle was made of C. kousa

Fig. 7.

Bamboo trays are commonly used to dry plants for winter

Fig. 8.

Sieve walls are made of Betula albosinensis wood

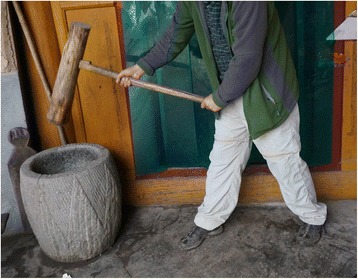

Fig. 9.

A ciba hammer used for pounding some foodstuffs

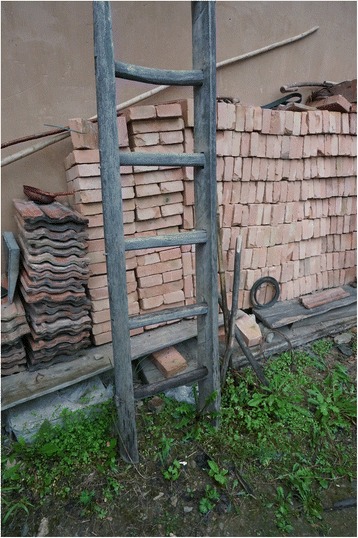

Fig. 10.

A ladder made of Tilia

Fig. 11.

A walking stick made of Berchemia sinica

Fig. 12.

A broom made of locally grown Phyllostachys bamboo

Fig. 13.

A cuopiao grain shovel made of Populus purdomii

Fig. 14.

A plough made of Ulmus wood

Fig. 15.

A harrow (mu) with ‘teeth” made of Cotinus wood

Fig. 16.

Boards supporting tiles are often made of Toxicondendron vernicifluum wood

Fig. 17.

Coffins are made or bought by elderly people in preparation for death and kept in the attic. These coffins were made of Tsuga chinensis

Fig. 18.

A biandan carrying stick made of Morus australis wood

Fig. 19.

A trough for feeding farm animals made of Castanea wood

Fig. 20.

A ten-year old fence made from Cotinus sticks

Fig. 21.

Traditional beehives are made of halved hollowed trunks of softwood deciduous trees (Populus, Paulownia)

Fig. 22.

Up until recently electricity poles were made of Castanea trunks

Fig. 23.

A washboard made of Pinus tabuliformis wood

Table 1.

The main emic categories of construction and tool plant use in the studied valley

| Type of use | Use reports | Most preferred/used species |

|---|---|---|

| Furniture | 92 | Prunus stellipila, Fraxinus mandshurica |

| Construction | 91 | Pinus tabuliformis, Pinus armandii |

| Chopping boards | 81 | Prunus stellipila, Betula albosinensis, Pyrus sp. |

| Pick-axe handles | 57 | Cornus kousa |

| Spade handles | 53 | Meliosma dillenifolia |

| Doors | 52 | Pinus tabuliformis, Pinus armandii |

| Ladders | 50 | Pinus armandii, Pinus tabuliformi, |

| Carrying sticks | 44 | Morus alba |

| Beehives | 42 | Populus purdomii, Paulownia tomentosa |

| Shoes | 41 | Tilia spp. |

| Barrels | 39 | Platycladus orientalis, Catalpa fargesii |

| Tables | 38 | Prunus stellipila |

| Hoe handles | 37 | Cornus kousa, Meliosma dillenifolia |

| Coffins | 34 | Tsuga chinensis |

| Baskets | 32 | Phyllostachys spp., Fargesia nitida |

| Rolling pins | 32 | Buxus sinica, Betula albosinensis, Cornus controversa, Stachyurus chinensis |

| Walking sticks | 31 | Philadelphus incanus |

| Chairs | 28 | Prunus stellipila |

| Windows | 28 | Pinus tabuliformis, Pinus armandii |

| Firewood | 22 | Quercus aliena |

| Roof materials | 18 | Cotinus coggygria |

| Bridges | 16 | Castanea mollissima |

| Basket Handles | 15 | Berchemia sinica |

| Fences | 13 | Castanea mollissima, Toxicodendron vernicifluum |

| Ropes | 12 | Pueraria montana var. lobata |

| Grain shovels | 12 | Salix spp., Pterocarya macroptera |

| Fork handles | 11 | Meliosma dillenifolia |

| Harrow (teeth) | 10 | Euonymus alatus |

| Sickle handles | 9 | Cornus kousa |

| Ciba Hammers | 9 | Eucommia ulmoides, Ulmus macrocarpa |

| Ploughs | 6 | Cornus spp., Quercus spp. |

| Rake handles | 4 | Cornus kousa |

Table 2.

Most salient species freelisted by the interviewees

| Latin name | Smith’s Salience Index |

|---|---|

| Pinus tabuliformis Carrière | 35.5 |

| Pinus armandii Franch. | 27.9 |

| Prunus stellipila Koehne | 23.5 |

| Betula albosinensis Burkill | 18.5 |

| Cornus kousa F.Buerger ex Hance | 18.0 |

| Meliosma dilleniifolia (Wall. ex Wight & Arn.) Walp. | 17.0 |

| Fraxinus mandshurica Rupr. | 16.1 |

| Tsuga chinensis (Franch.) Pritz. | 13.6 |

| Populus purdomii Rehder | 11.8 |

| Catalpa fargesii Bureau | 11.5 |

| Quercus aliena var. acutiserrata Maxim. | 11.1 |

| Morus australis Poir. | 10.8 |

| Castanea mollissima Blume | 10.4 |

| Toona sinensis (Juss.) M.Roem. | 9.6 |

| Tilia olivieri Szyszył. and T. paucicostata Maxim. | 9.4 |

| Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle | 9.0 |

| Populus cathayana Rehder | 9.0 |

| Platycladus orientalis (L.) Franco | 8.9 |

| Phyllostachys sp. | 8.5 |

| Cornus controversa Hemsl. | 7.7 |

Table 3.

The list of species used for construction, furniture and other handicrafts

| Latin name | Local name | Local name (Chines characters) | No. of citations | Part | Use | Voucher numbers, begin with WUK Kang |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinus tabuliformis Carrière | songmu | 松木 | 37 | wood | house construction esp. roofs, furniture, ladders, beehives | K198 |

| Prunus stellipila Koehne | kutao | 苦桃 | 34 | wood | mainly furniture and chopping boards | K101,103 |

| Pinus armandii Franch. | madengsong | 马灯松 | 31 | wood | house construction, furniture, doors, windows, ladders | K157 |

| Betula albosinensis Burkill | honghua, huamu, | 红桦,桦木 | 30 | wood and bark | wood for chopping boards, stools, also rolling pins; bark for hats and steamers | K164 |

| Fraxinus mandshurica Rupr. | shuiquliu | 水曲柳 | 30 | wood | highly valued for furniture, also window frames, handles (esp. spades), carrying sticks etc. | K140 |

| Castanea mollissima Blume | maoli | 毛栗 | 27 | wood | best for electricity posts and for boards in bridges, also pig troughs, roof elements, door frames | k132 |

| Cornus kousa F.Buerger ex Hance | shizao | 石枣子 | 26 | wood | handles (axe, hoe, sickle), also rolling pins and stone grinder axes, and firewood | K155 |

| Meliosma dilleniifolia (Wall. ex Wight & Arn.) Walp. | linshu, xiangnongmu | 林寿,降龙木 | 26 | wood | highly valued for handles (esp. hoe, spade and rake) - very smooth and durable | K118 |

| Populus purdomii Rehder | dongguayang, baiyang, yangshu | 冬瓜杨,白杨,杨树 | 26 | wood | mainly for bee-hives, also “cuopiao” grain shovels | K180 |

| Tilia olivieri Szyszył. and T. paucicostata Maxim. | duanmu, duanshu | 椴木(树) | 26 | bark and wood | mainly bark for shoes, also wood for beehives, ladders, musical instruments, boxes and furniture | K184, K187 |

| Catalpa fargesii Bureau | tangqiu | 唐楸 | 23 | wood | mainly for barrels, also for furniture due to its attractive texture and grain | K113 |

| Phyllostachys sp. | shuizhu, jinzhu, banzhu, zhuzi | 水竹,金竹,斑竹,竹子 | 23 | above ground parts | mainly baskets, also basket handles, fishing rods, washing up brushes | K133, K134 |

| Quercus aliena var. acutiserrata Maxim. | gangmu | 杠木 | 23 | wood | construction esp. for beams, pillars, floor boards; best for firewood, also handles and “muer” mushroom cultivation | K181 |

| Tsuga chinensis (Franch.) Pritz. | zaosong | 枣松 | 22 | wood | mainly coffins and furniture, also construction (eg roof rafters) and barrels | K148 |

| Morus australis Poir. | sangmu | 桑木 | 21 | wood | carrying sticks | K156 |

| Philadelphus incanus Koehne | jigutou | 鸡骨头 | 18 | wood | walking sticks | K163 |

| Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle | baichun | 白椿 | 17 | wood | furniture, esp. boards for windows and doors, also for table and chair legs and chopping boards | K177 |

| Platycladus orientalis (L.) Franco | baimu, xiangbai | 柏木,香柏 | 17 | wood | mainly water barrels and containers, and coffins | K121 |

| Toona sinensis (Juss.) M.Roem. | hongchun | 红椿 | 17 | wood | mainly for furniture, windows and door planks | K144 |

| Cornus controversa Hemsl. | liangzimu | 梁子木 | 15 | wood | hard wood for chopping boards, furniture legs and rolling pins, also for handles | K109, K128 |

| Pyrus sp. | limu | 梨木 | 15 | wood | mainly chopping boards | K165 |

| Quercus variabilis Blume | xiangmu, xiangshu | 橡木(树) | 15 | wood and bark | best for firewood, handles (basket, axe, plough), bark for industry and shoe soles, “muer” mushroom cultivation, furniture, boards | K160 |

| Berchemia sinica C.K.Schneid | yagutiao | 牙骨条 | 14 | wood | mainly for walking sticks, cattle harnesses and basket handles, also pitch-fork fingers | K126 |

| Cotinus coggygria Scop. | huanglou | 黄栌 | 14 | wood | mainly for roof elements supporting tiles, also for “mu” harrows and fence posts | K119 |

| Magnolia sprengeri Pamp. | jiangbo, mubieshu | 姜剥 | 14 | wood | mainly for high quality chopping boards | K138 |

| Paulownia tomentosa Steud. | tongmu | 桐木 | 14 | wood | mainly for beehives, also barrels, pot covers, ladders, coffins and low-weight boards | K170 |

| Toxicondendron vernicifluum (Stokes) F.A. Barkley | qimu, qishu | 漆木(树) | 14 | wood and secretion | mainly for electricity posts, also for barrels, fences, boards under tiles, stem sap used for lacquer | K152 |

| Pueraria montana var. lobata (Willd.) Sanjappa & Pradeep | geteng, getiao | 葛藤,葛条 | 13 | wood | fibre for shoes, ropes and baskets | K143 |

| Fargesia nitida (Mitford) Keng f. ex T.P.Yi | songhuazhu, zhuzi | 松花竹,竹子 | 12 | above-ground parts | brooms and baskets | K188 |

| Populus cathayana Rehder | baiyang, yangmu | 白杨,杨木 | 12 | wood | mainly construction material and ladders, also fence posts, troughs and shovels | K127 |

| Abies fargesii Franch. | pumu, pusong | 朴木,朴松 | 11 | wood | construction, coffins, ladders | K125 |

| Salix sp. | liu, liumu, liutiao | 柳,柳木,柳条 | 10 | wood, year-old twigs, bark | shovels, twigs for baskets, bark for shoes, also firewood | K158 |

| Cornus officinalis Siebold & Zucc. | zaopi | 枣皮 | 9 | wood | mainly handles (spades, axes) and firewood, also ploughs | K189 |

| Pterocarya macroptera Batalin | maliu | 麻柳 | 9 | wood and bark | wood, mainly shovels and dustpans, bark for making shoes | K147 |

| Ulmus macrocarpa Hance | yumu | 榆木 | 9 | wood | a variety of small objects: “ciba” hammers, “mu” harrows, ladders, basket handles, ploughs, furniture | K174 |

| Amelanchier sinica (C.K.Schneid.) Chun | hongshenzi, hongshunzi | 红绳子,红顺子 | 8 | wood | mainly handles (for hoe, axe, rake), baskets | K106 |

| Juglans regia L. | hetao | 核桃 | 8 | wood | furniture, feet of door frames | K137 |

| Quercus spinosa David | tiejiamu | 铁匠木 | 8 | wood | mainly for handles (hoe, axe), wooden hammers, rolling pins, axes of stone grinders, firewood | K159 |

| Symplocos paniculata (Thunb.) Miq. | baihuacha | 百花茶 | 8 | wood | handles (sickle, hoe, axe, spade) | K131 |

| Buxus sinica (Rehder & E.H.Wilson) M.Cheng | huangyang | 黄杨 | 7 | wood | very hard wood, the best material for rolling pins and carving elements of Chinese board games “xianqi” and “majiang” | K167 |

| Eucommia ulmoides Oliv. | duzhong | 杜仲 | 6 | wood | a very good handle for hoes, material for “ciba” hammers | K190 |

| Fraxinus platypoda Oliv. | baixingmu | 白芯木 | 6 | wood | handles (axe, spade), also furniture esp. legs | K117 |

| Sorbus folgneri (C.K.Schneid.) Rehder | baishenzi | 白绳子 | 6 | wood | handles (hoe, axe, spade) | K108 |

| Acer stachyophyllum Hiern (syn. Acer tetramerum Pax) | hongliu | 红柳 | 5 | wood | handles, esp. hoe, spade and pick-axe | K175 |

| Juglans mandshurica Maxim. | mahetao | 麻核桃 | 5 | bark | bark for shoes and ropes | K191 |

| Picea wilsonii Mast. | zimu | 紫木 | 5 | wood | construction and coffin boards | K124 |

| Stachyurus chinensis Franch. | tonghuagan | 通花杆 | 5 | wood | mainly rolling pins, also arms of scales, walking sticks, instruments for blowing fire | K149 |

| Cannabis sativa L. | huoma | 火麻 | 4 | annual above ground parts | fibre for shoes and ropes | K192 |

| Prunus tomentosa Thunb. | chuantao | 川桃 | 4 | wood | “lianjia” flails, basket handles, firewood | K161 |

| Bassia scoparia (L.) A.J.Scott | saozhoucai | 扫帚菜 | 3 | above-ground parts | brooms | |

| Betula luminifera H.J.P.Winkl. | miaoyumu | 描榆木 | 3 | wood | carrying sticks, firewood | K120 |

| Broussonetia papyrifera (L.) L’Hér. ex Vent. | goushu | 构树 | 3 | bark | bark for shoes and ropes | K176 |

| Juniperus chinensis L. | baishu, yabei | 柏树,崖柏 | 3 | wood | decorative roots (“gendiao”), body ornaments due to pleasant smell, furniture | K129 |

| Lonicera standishii Jacques | jigutou, paoer, yangnaishu | 鸡骨头,泡儿,羊奶树 | 3 | wood | walking sticks, handles (sickle, axe), rolling pins | K145 |

| Maackia hupehensis Takeda | chouhuai, honghuai | 臭槐,红槐 | 3 | wood | ladders, stools, handles (wheel barrows) | K182 |

| Prunus davidiana (Carriere) Franch. | shantao | 山桃 | 3 | wood | chopping boards, rolling pins, branches to drive ghosts away | K169 |

| Viburnum betulifolium Batalin | cusuantiao, nuomitiao | 苦酸条,糯米条 | 3 | wood | axe handles, rolling pins, rakes, “mu” harrows | K142 |

| Corylus heterophylla Fisch. ex Trautv. | zhenzi | 榛子 | 2 | wood | handles (hoe, axe), frames for garden climbers | K171 |

| Euonymus alatus (Thunb.) Siebold | bashu | 巴树(木) | 2 | wood | “mu” harrows | K193 |

| Kalopanax septemlobus (Thunb.) Koidz. | ciqiu | 刺楸 | 2 | wood | furniture | K122 |

| Paederia foetida L. | hongteng, jishiteng | 红藤,鸡屎藤 | 2 | wood | baskets, ropes | K194 |

| Rhododendron sp. | doujuan, pipa | 杜鹃,枇杷 | 2 | wood | rolling pins, “xiba” washing sticks | K173 |

| Rhus potaninii Maxim. | wubeizi | 五倍子 | 2 | wood | electricity posts, barrels | K151 |

| Sophora japonica L. | huaimu, huaishu | 槐木(树) | 2 | wood | furniture, chopping boards | K183 |

| Taxus wallichiana var. chinensis (Pilg.) Florin | hongdoushan | 红豆杉 | 2 | wood | barrels and containers for water | K123 |

| Viburnum schensianum Maxim. | heichagun | 黑茶棍 | 2 | wood | mainly wooden fork fingers, also basket handles, “mu” harrows, “lianjia” flails | K179 |

| Akebia trifoliata (Thunb.) Koidz. | mutong | 木通 | 1 | wood | ropes | |

| Betula platyphylla Sukachev | huashu | 桦树 | 1 | wood | firewood | K153 |

| Caragana arborescens Lam. | yangqiuhua | 洋秋花 | 1 | wood | brushes for cleaning kitchen pots, “mu” harrow teeth | K186 |

| Cephalotaxus sinensis (Rehder & E.H.Wilson) H.L.Li | shubai | 水柏 | 1 | wood | basket handles | K195 |

| Chaenomeles sinensis (Dum.Cours.) Koehne | muguahaitang | 木瓜海棠 | 1 | wood | walking sticks | k196 |

| Crataegus cuneata Siebold & Zucc. | yeshanza | 野山楂 | 1 | wood | chopping boards, table legs | K197 |

| Dipteronia sinensis Oliv. | shanmagan | 山麻杆 | 1 | wood | big barrels for water and alcohol fermentation | K116 |

| Elaeagnus umbellata Thunb. | jianzici | 剪枝刺 | 1 | wood | pitch-forks | K136 |

| Juniperus squamata Buch.-Ham. ex D.Don | yabei | 崖柏 | 1 | wood | big barrels for water or spirits | K199 |

| Larix gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii (Mayr) Pilg. | luoyesong | 落叶松 | 1 | wood | boards | K135 |

| Ligustrum sp. | duijetiao | 对节条 | 1 | wood | fork fingers | K162 |

| Malus pumila Mill. | pingguoshu | 苹果树 | 1 | wood | “ciba” hammers | K166 |

| Miscanthus sinensis Andersson | maocao | 茅草 | 1 | wood | roof thatching | K141 |

| Prunus sp. | choutao | 臭桃 | 1 | wood | chopping boards | K102 |

| Rhus chinensis Mill. | fulianzi | 伏莲子 | 1 | wood | charcoal for fireworks | K172 |

| Sorbaria kirilowii (Regel & Tiling) Maxim. | gaolianggan | 高粱杆 | 1 | wood | rolling pins | K185 |

| Vitex negundo L. | huangjintiao | 黄荆条 | 1 | wood | basket handles | k178 |

The authorities of Houzhenzi Forest farm in Shaanxi Forestry Bureau in Xi’an and park rangers were also consulted about the conservation status of trees in the study area.

In order to measure the cultural importance of particular wild foods we used Smith’s Salience Index [28]. The index for species A is the mean of the following ratio calculated for each free listed plant:

Thus a species which is always quoted first gets an index which equals 1 and the items quoted at the end of the freelists tend to have Smith’s indexes close to 0.

Voucher specimens of plants were deposited in the Herbarium of the Northwest A&F University in Yangling (WUK). Plants were identified using the standard identification key concerning local floras, and their names follow the Plant List [29].

Results

Altogether, 84 species of plants were recorded as material for construction and handicraft plants (Tables 1, 2 and 3). Of these, 80 species are used for their wood and five species for bark. Two herbaceous species and two bamboo taxa were used (Table 3). The most frequently mentioned plants were: Pinus tabuliformis Carrière, Prunus stellipila Koehne, Pinus armandii Franch., Betula albosinensis Burkill, Fraxinus mandshurica Rupr., Castanea mollissima Blume, Cornus kousa F.Buerger ex Hance, Meliosma dilleniifolia (Wall. ex Wight & Arn.) Walp., Populus purdomii Rehder, Tilia olivieri Szyszył. and T. paucicostata Maxim. (Table 3). The ranking of most salient species is nearly identical to that of those most frequently mentioned (Table 2).

Both the mean and median number of species mentioned per interview was 22.

All the large-sized tree species are used in some form by the local inhabitants. Among shrubby species and small trees those which have very hard wood are used to make handles, walking sticks or small objects like forks and harrow teeth. The bark of a few species was used to make shoes, hats, steamers and ropes, but this tradition is nearly gone. A few species, mainly bamboo, are used for basket making and year-old willow branches are used for brushing off the chaff during wheat winnowing. The use of large pieces of local timber has greatly diminished due to the protection regime, and is now limited to the trees growing in the land around houses. On the other hand, the wood for such objects as tool handles, bee hives, walking sticks and carrying sticks is still commonly used from local trees.

We recorded a few dozen emic categories of use. The most frequently mentioned categories were listed in Table 1. A few of the most commonly used tree species have many uses, but among the trees used with medium frequency some have very specialized uses restricted to one particular application. For example Morus australis is the preferred wood for carrying sticks (a stick where two buckets are attached on each side), Philadelphus incanus for making walking sticks, Castanea mollissima for electricity poles, Cotinus coggygria for making small boards supporting ceramic tiles in the roof, Tsuga chinensis – coffins, Meliosma dillenifolia and Cornus kousa – tool handles. Pinus spp. is used for the main construction of houses, windows and doors. The materials for making chopping boards and rolling pins are more diverse, though for the former Prunus stellipila and for the latter Buxus sinica is preferred. Firewood is usually collected from any available wood, though Quercus and Betula are preferred.

All the households contain many self-made wooden tools. These tools are usually made only for farmers’ use and are neither bought or sold. Such items as furniture, coffins, handles or shovels are still commonly made. On the other hand the manufacturing of bark shoes disappeared in the 1980s and we could not find a single such shoe preserved in the valley, although many people still know how to make them. The production of wooden barrels is also dying out.

Discussion

It is difficult to compare our data with other places in China as similar studies are lacking.

One of the factors which makes the sale of wooden items hard, even for those skilled in making them, is the protection status of the surrounding forest. No commercial large scale logging has been performed in the area since 1987, when it was designated as a water resource area for the city of Xi’an. Wood is only cut for local purposes for farmers’ use. The monitoring of timber use is important for forest conservation [30–32]. Our results suggest that some rare and endangered tree species may have been selectively cut by local people due to their valuable wood, e.g. Fraxinus mandshurica and Taxus wallichiana var. chinensis. Some other rare species, e.g. Dipteronia sinensis, are little used and little valued.

All the local large canopy trees are used for some purpose. From among smaller trees and shrubs, those which are particularly hard are selectively cut. From all the larger trees more common in the area, Pterocarya is used the least. It is also striking that only one species of Acer was mentioned, although a few other species of this genus grow in the forests. They tend, however, to grow above the villages, at slightly higher altitudes, and they are not attractive due to their shrubby growth. Some other common shrubs, like Spiraea were not mentioned either.

The use of smaller tree species is also very common, as they usually grow on farmer’s parcels. According to regulation no. 32 in chapter 5 of the “State Forest protection Laws,” [33] private trees in farmers’ parcels around their dwellings can be utilized by local residents, even in National Forest Parks. For example, local people planted a plantation of Cornus officinalis on their own land for money, but in recent years the price of the fruit of this species has become very low. So many people felled the C. officinalis plantations and the wood was used to make tools or firewood. According to the information we got from the nature conservation authorities local residents occasionally get permission to cut Castanea trees in the state part of the forest for the construction of bridges, whereas construction timber is now imported from outside the park borders. The demand for construction timber has also been diminished by the use of non-wooden construction materials (e.g. concrete). Some wood is also available to local residents as a leftover from forest management (e.g. removing trees attacked by pests).

It is very striking that hardly any superstitious beliefs were recorded when talking about trees. No trees were treated as particularly lucky (auspicious) or unlucky, as is very common in other parts of the world [34], and despite the presence of such beliefs in the traditional fengshui system [35].

Although some plant uses are well known, probably across large parts of China, particularly those concerning large hardwoods used for construction and furniture, or bamboo (see e.g. [36], some uses of rarer small trees and shrubs in handicrafts may be endemic to this part of China, and be worth recording.

Conclusions

The high diversity of woody species facilitates the preservation of rich knowledge about the properties of many lesser known kinds of wooden materials. In spite of social changes, some tools and utensils are still handmade (handles, chopping boards, furniture), whereas other handicrafts have completely disappeared (bark shoes, ropes) or are disappearing (barrels). Generally, the impact of these activities on the tree population is probably very low.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

The field study and publication costs were financed by the Northwest A&F University in Yangling, China.

Availability of data and materials

A structured and organized version of the data matrix was deposited in the Digital Repository of the University of Rzeszów (http://repozytorium.ur.edu.pl/handle/item/2474). Voucher specimens were deposited in the herbarium of the Forestry Department of the North-West A&F University in Yangling (WUK).

Authors’ contributions

Field study – JK, YK, JF, ML, ŁŁ. Further elaboration of data – all the authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research adhered to the local traditions for such research and the Code of Ethics of the International Society of Ethnobiology (ISE 2008). Prior oral informed consent was obtained from all study participants. No ethical committee permits were required. No permits were required to collect voucher specimens.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jin Kang, Email: 250367563@qq.com.

Yongxiang Kang, Email: yxkang@nwsuaf.edu.cn.

Jing Feng, Email: fengjing@nwsuaf.edu.cn.

Mengying Liu, Email: 2451590810@qq.com.

Xiaolian Ji, Email: 267364916@qq.com.

Dengwu Li, Email: dengwuli@163.com.

Kinga Stawarczyk, Email: kstawarczyk2@o2.pl.

Łukasz Łuczaj, Email: lukasz.luczaj@interia.pl.

References

- 1.Cunningham AB. Applied Ethnobotany; people, wild plant use and conservation: London and Sterling. London and Sterling, VA: Earth Scan Publication Limited; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falconer J, Koppell CR. The major significance of'minor forest products: the local use and value of forests in the West African humid forest zone. FAO Community Forestry Note; 1990.

- 3.De Beer JH, McDermott MJ. The economic value of non-timber forest products in Southeast Asia: with emphasis on Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand. Amsterdam: Netherlands Committee for International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belcher B, Schreckenberg K. Commercialisation of non-timber forest products: a reality check. Dev Policy Rev. 2007;25(3):355–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7679.2007.00374.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perez MR, Byron N. A methodology to analyze divergent case studies of non-timber forest products and their development potential. For Sci. 1999;45(1):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chamberlain J, Bush R, Hammett AL. Non-timber forest products. Forest Prod J. 1998;48:10. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nedelcheva A, Dogan Y, Obratov-Petkovic D, Padure IM. The traditional use of plants for handicrafts in southeastern Europe. Hum Ecol. 2011;39(6):813–828. doi: 10.1007/s10745-011-9432-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nedelcheva AM, Dogan Y, Guarrera PM. Plants traditionally used to make brooms in several European countries. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2007;3(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-3-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reddy KN, Pattanaik C, Reddy CS, Murthy EN, Raju VS. Plants used in traditional handicrafts in north eastern Andhra Pradesh. Indian J Tradit Know. 2008;7(1):162–165. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salerno G, Guarrera PM, Caneva G. Agricultural, domestic and handicraft folk uses of plants in the Tyrrhenian sector of Basilicata (Italy) J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2005;1(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guarrera PM. Handicrafts, handlooms and dye plants in Italian folk traditions. Indian J Tradit Know. 2008;7(1):67–69. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ertug F. Plants used in domestic handicrafts in Central Turkey. OT Sistematic Botanik Dergisi. 1999;6(2):57–68. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carvalho AM, Pardo de Santayana M, Morales R. Traditional knowledge of basketry practices in a Northeastern region of Portugal. In: Ethnobotany at the junction of the Continents and the disciplines. Instanbul: Proc Fourth Int Cong Ethnobot, (ICEB 2005). 2006;335–8.

- 14.Łuczaj Ł. Bladdernut (Staphylea Pinnata L.) in polish folklore. Rocz Polski Tow Dendrologicznego. 2009;57:23–28. [Google Scholar]

- 15.He J, Zhou Z, Weyerhaeuser H, Xu J. Participatory technology development for incorporating non-timber forest products into forest restoration in Yunnan, Southwest China. Forest Ecol Manag. 2009;257(10):2010–2016. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2009.01.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fu Y, Chen J, Guo H, Chen A, Cui J, Hu H. The role of non-timber forest products during agroecosystem shift in Xishuangbanna, southwestern China. Forest Policy Econ. 2009;11(1):18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2008.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donovan DG. Strapped for cash: Asians plunder their forests and endanger their future. Asia-Pacific issues paper no.39. Honolulu: East-West Center; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghorbani A, Langenberger G, Liu JX, Wehner S, Sauerborn J. Diversity of medicinal and food plants as non-timber forest products in Naban River watershed National Nature Reserve (China): implications for livelihood improvement and biodiversity conservation. Econ Bot. 2012;66(2):178–191. doi: 10.1007/s12231-012-9188-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White A, Sun X, Canby K, Xu J, Barr C, Cossalter C, et al. China and the global market for forest products: transforming trade to benefit forests and livelihoods. Washington, DC: Forest Trends; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang Y, Łuczaj Ł, Yes S, Zhang S, Kang J. Wild food plants and wild edible fungi of Heihe valley (Qinling Mountains, Shaanxi, central China): herbophilia and indifference to fruits and mushrooms. Acta Soc Bot Pol. 2012;81(4):405–413. doi: 10.5586/asbp.2012.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang Y, Łuczaj Ł, Kang J, Zhang S. Wild food plants and wild edible fungi in two valleys of the Qinling Mountains (Shaanxi, central China) J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2013;9(1):26. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang Y, Łuczaj Ł, Ye S. The highly toxic Aconitum Carmichaelii Debeaux as a root vegetable in the Qinling Mountains (Shaanxi, China) Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2012;59:1569–1575. doi: 10.1007/s10722-012-9853-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.http://ww.agri.com.cn/population/610124108000.htm Accessed 20 Jan 2017.

- 24.Croll EJ. Research methodologies appropriate to rapid appraisal: a Chinese experience. IDS Bull. 1984;15(1):51–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1759-5436.1984.mp15001008.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Long CL, Wang JR. Participatory rural appraisal: an introduction to principle, methodology and application. Kunming: Yunnan Science and Technology Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Anthropological Association Code of Ethics. http://www.aaanet.org/issues/policy-advocacy/upload/AAA-Ethics-Code-2009.pdf. Accessed 10 Mar 2016.

- 27.International Society of Ethnobiology Code of Ethics(with 2008 additions). http://ethnobiology.net/code-of-ethics/Accessed 10 Mar 2016.

- 28.Smith JJ. Using ANTHROPAC 3.5 and a spreadshseet to compute a free list Salience index. Cult Anthropol Methods. 1993;5(3):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Plant List: a working list of all plant species. http://www.theplantlist.org/ Accessed 10 Dec 2016.

- 30.Yang Y. Impacts and effectiveness of logging bans in natural forests: People’s Republic of China. Forests out of bounds: impacts and effectiveness of logging bans in natural forests in Asia–Pacific. Bangkok: Food and Agricultural Office of the United Nations (FAO); 2001. pp. 81–102. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu C, Taylor R, Feng G. China's wood market, trade and the environment. Monmouth Junction, NJ: Science Press USA Incorporated; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richardson SD. Forests and forestry in China: changing patterns of resource development: Island Press; 1990.

- 33.State Forest protection Laws [in Chinese]. http://xzzf.forestry.gov.cn/portal/zfs/s/3261/content-970346.html. Accessed 28 May 2017.

- 34.De Cleene M, Lejeune M. Compendium of ritual plants in Europe. Vol. I: trees and shrubs. Ghent, Belgium: Man and Culture Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qiu X. Major forms and functions of rural Forest culture. Journal of Beijing Forestry Univ (Soc Sci) 2013;12(1):28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Renvoize S. From fishing poles and ski sticks to vegetables and paper – the bamboo genus Phyllostachys. Curtis's Bot Mag. 1995;12(1):8–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8748.1995.tb00480.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

A structured and organized version of the data matrix was deposited in the Digital Repository of the University of Rzeszów (http://repozytorium.ur.edu.pl/handle/item/2474). Voucher specimens were deposited in the herbarium of the Forestry Department of the North-West A&F University in Yangling (WUK).