Abstract

Setting: Mulanje District, Malawi.

Objective: To examine the effectiveness of door-to-door (DtD) testing in reaching young people and men in a remote, rural area with a high prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

Design: This was a retrospective analysis of data collected for a pilot DtD program. HIV testing services (HTS) visited targeted villages for 1–2 weeks. All current residents aged ⩾2 years not known to be HIV-positive were offered testing.

Results: Ninety per cent (13 783/15 391) of individuals eligible for testing accepted. Forty-one per cent (n = 5693) of those tested were males and 56% (n = 7752) were aged <20 years. The overall proportion who tested positive was 4% (n = 524), with half as many males as females testing positive (OR 0.49, 95%CI 0.40–0.60, P < 0.001). There was a higher positive yield rate for those aged ⩾20 years (6% for men and 8% for women). Two thirds were first-time testers; males were half as likely as females to have been previously tested (OR 0.43, 95%CI 0.40–0.47, P < 0.001).

Conclusion: DtD-HTS can be an effective way to reach populations in remote, rural high-prevalence areas where access to fixed facilities is inadequate. It has the potential to reach young people and men better than facility-based testing or other community strategies, and can identify young HIV-positive children who may have been missed by other methods.

Keywords: operational research, male testing, testing of young people, community-based testing

Abstract

Contexte: Le district de Mulanje, Malawi.

Objectif: Examiner l'efficacité d'un test pour le virus de l'immunodéficience humaine (VIH) en porte à porte (DtD) pour atteindre les jeunes et les hommes dans une zone rurale isolée, à prévalence élevée du VIH.

Schéma: Une analyse rétrospective des données recueillies lors d'un programme pilote DtD. Des services de test du VIH (HTS) ont été offerts pendant 1–2 semaines dans les villages ciblés. Tous les résidents actuels (âgés de ⩾2 ans) non connus comme VIH positifs ont été invités à bénéficier du test.

Résultats: Il y avait 90% (13 783/15 391) des individus éligibles au test qui ont accepté. Parmi les patients testés, 41% (n = 5693) ont été des hommes et 56% (n = 7752) avaient <20 ans. Le pourcentage total de tests positifs a été de 4% (n = 524), avec deux fois moins d'hommes VIH-positifs (OR 0,49, IC95% 0,40–0,60 ; P < 0,001) et le rendement a été plus élevé pour les patients âgés de ⩾20 ans (6% pour les hommes et 8% pour les femmes). Pour les deux tiers des patients, il s'agissait du premier test, les hommes étant deux fois moins susceptibles d'avoir été testés auparavant (OR 0.43, IC95% 0,40–0,47 ; P < 0,001).

Conclusion: Les services de test DtD peuvent être une manière efficace d'atteindre les populations dans les zones rurales isolées, avec une prévalence élevée de VIH, où l'accès aux structures fixes est insuffisant. Cette stratégie aura le potentiel d'atteindre les jeunes et les hommes mieux que les tests en structures de santé ou les stratégies communautaires, et peuvent identifier les jeunes enfants VIH-positifs qui peuvent avoir été manqués par les autres méthodes.

Abstract

Marco de referencia: El distrito de Mulanje, en Malawi.

Objetivo: Examinar la eficacia de la oferta de la prueba diagnóstica de puerta a puerta con el objeto de llegar a los jóvenes y los hombres en una zona rural remota donde existe una alta prevalencia de infección por el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana (VIH).

Método: Un análisis retrospectivo de los datos recogidos para un programa piloto de puerta a puerta. Se logró una cobertura completa de las aldeas destinatarias con servicios de diagnóstico del VIH durante 1 a 2 semanas. Se ofreció la prueba a todos los residentes actuales (⩾2 años de edad), con la excepción de quienes conocían su situación positiva frente al VIH.

Resultados: El noventa por ciento de las personas que cumplían los requisitos aceptaron la prueba (13 783/15 391), de las personas en quienes se practicó, 41% eran de sexo masculino (n = 5693) y 56% <20 años (n = 7752). El porcentaje global de resultados positivos fue 4% (n = 524), la mitad de los hombres obtuvieron un resultado positivo (OR 0,49; IC95% 0,40–0,60; P < 0,001) y se observó una mayor tasa de resultados positivos en las personas ⩾20 años (6% en los hombres y 8% en las mujeres). En dos tercios de los casos se trató de una primera prueba y la probabilidad de haber tenido una prueba en el pasado fue de 50% en los hombres (OR 0,43; IC95% 0,40–0,47; P < 0,001).

Conclusión: Las pruebas diagnósticas del VIH practicadas de puerta a puerta pueden ser un método eficaz de alcanzar a las poblaciones con alta prevalencia de la infección VIH en regiones rurales remotas, que no cuentan con un acceso adecuado a los establecimientos de salud. Esta estrategia ofrece una mejor posibilidad de llegar a los jóvenes y los hombres que las pruebas institucionales u otras estrategias comunitarias y puede detectar a los niños pequeños positivos frente al VIH que se han pasado por alto con otros métodos.

Reaching the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS) 90–90–90 targets by the year 2020—in which 90% of people living with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) know their status, 90% of those diagnosed with HIV receive sustained antiretroviral therapy (ART), and 90% of those receiving ART are virally suppressed—in remote, high-prevalence areas in Africa such as Malawi, requires targeted interventions to reach individuals far off the health-care grid. In Malawi, the effects of poverty limit people's ability to travel to fixed testing sites such as hospitals and health centers, making testing at these sites difficult to access.1

Men are particularly challenging to test. They have fewer opportunities for testing due to programmatic targeting of women and children.2 Cultural norms associated with masculinity, having strength and being the breadwinner, along with the perception that hospitals and clinics are female spaces, create barriers to care.3 While provider-initiated counseling and testing has increased access to testing for both men and women, men are less likely to seek care when ill, while women, through pregnancy and child care, interact with the health system more regularly.4 The testing rates among men and women thus differ widely: in Malawi, 82% of women have been tested for HIV compared to 68% of men.5 Adolescents and young people are another group of concern, as recent reports show their HIV incidence is rising, with girls and young women aged 15–24 years accounting for 25% of new HIV infections among adults, although they represent only 17% of the population.6

There is, however, evidence from Malawi that home-based HIV testing services (HTS) using rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) can overcome many of these barriers and achieve high uptake for children and adults due to their perceived convenience, confidentiality and credibility.7 Home-based HTS can find HIV infections earlier than facility-based testing, improving the likelihood of successful treatment outcomes, particularly in cases of missed mother-to-child transmission.8 While door-to-door (DtD) testing programs generally have a lower HIV positivity yield than fixed facility or mobile approaches, a Lesotho study found a high yield of first-time testers, especially among young people and adolescents.9 Furthermore, men have been found to prefer home-based testing over facility-based and voluntary partner testing services.10

To meet the UNAIDS 90–90–90 goals, more intensive efforts are required to reach every individual with an opportunity for testing, and in particular men and young people. This paper describes the implementation of the Global AIDS Interfaith Alliance (GAIA, San Rafael, CA, USA) DtD-HTS pilot program and reports the results of the program through a retrospective analysis of program data. Specific aims were 1) to assess the demographic characteristics of those identified for DtD-HTS, 2) to assess the uptake of DtD-HTS by sex and age group, and 3) to assess the HTS outcomes by previous testing status, sex and age group.

METHODS

Design

This was a retrospective analysis of HTS program data collected for a DtD pilot program serving 57 villages in Malawi from 23 September 2015 to 30 September 2016.

Setting

Mulanje District, Malawi, is a high HIV prevalence area where the majority of the population are subsistence farmers. Located in the south, Mulanje District has a population of 670 000 across 577 villages, 51% of whom live below the national poverty line.11 Mulanje's adult HIV prevalence is nearly double the national average, at 17%.12 Since 2008, GAIA has worked to increase demand for HTS in Mulanje through a community-based health intervention, and has expanded access to HTS through mobile health clinics. Data from a survey of clients from GAIA programs revealed that 8% were within 1 hour's walk of a government health facility. The 57 villages targeted for DtD-HTS were located in one traditional authority (county) within Mulanje District. The villages chosen were a convenience sample served by other GAIA programs and adjacent villages. These villages were situated an average of 27 km from the district hospital and 2–8 km from the nearest government health facility.

The DtD-HTS program

Permission to implement the DtD-HTS program was obtained from the District Health Office of Mulanje District, Malawi. Sensitization meetings were conducted at the district level to inform relevant stakeholders. Sensitization also took place at the community level to obtain support from the village leadership (headmen/women), staff at the local health facilities, village health committees and faculty of local primary schools.

Seven HTS counselors traveling by bicycle, who were trained according to Malawi Ministry of Health HTS guidelines and overseen by two community health nurses traveling between villages on a motorbike, provided DtD-HTS.13 HTS was made available in each village for 1–2 weeks. The counselors notified each village headman/woman of the testing dates 1 week ahead of time. Two days before the first day of testing, each village headman/woman reminded community members that the DtD-HTS exercise would commence and encouraged them to take part. On the testing day, the counselors visited households, starting with those closest to the village headman/woman's home, and then advancing to peripheral dwellings. In some cases, the village headman/woman would arrange an alternative strategy if other activities taking place in the village were going to interfere with the usual pattern. Testing was conducted from 10 am to 3 pm on weekdays. Testing was conducted inside the home, starting with adult (aged ⩾15 years) members of the household and then children (aged 2–14 years), provided the parent/guardian consented. Determine™ (Alere, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) was used for the initial test, and if a reaction occurred, a Uni-Gold™ test (Trinity Biotech Plc, Wicklow, Ireland) was used to confirm the result.

Participants

The individuals identified and enumerated for the study were all those who had resided in households within the target villages for at least 2 months. Any individuals who lived or worked outside of the district more than half of the time were excluded. Eligibility criteria for testing included being aged ⩾2 years (those aged <2 years at risk for HIV were enumerated for the study, but were referred to the nearest health center for care). Individuals who self-identified as being HIV-positive were enumerated for the study but not tested. Households where no residents were home on any of the testing days could not be enumerated and were excluded from the study population. Appointments were made for residents who wished to be tested but were unavailable at the first visit. Individuals known to live in the villages but who were missed on the first and second attempts were recorded as unreachable.

Variables

Independent variables for the study included sex, age and date of visit/repeat visit. Outcome variables included HTS acceptance, previous testing status and test result.

Data sources

All variables were included in a standardized paper data collection form. The form was designed to capture all necessary information for the Malawi Ministry of Health HIV testing and counseling register. Data from the paper forms were entered into the DtD-HTS Excel database (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA, USA) by a data clerk and then cross-checked by a data manager to assure accurate entry. Each client was given a unique identifier in the database. To further protect client privacy, all forms were locked in the field office and the Excel database was password protected.

Statistical methods

Data analysis, including tabulating, reporting proportions and logistic regression to report odds ratios (OR) was performed in Microsoft Excel 2013 and Stata 11.2 SE (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA). Significance was assigned to values with P < 0.05.

Ethics approval

Ethics exemption approval for an audit of an ongoing program was obtained from the Malawi National Health Science Research Committee (Lilongwe, Malawi).

RESULTS

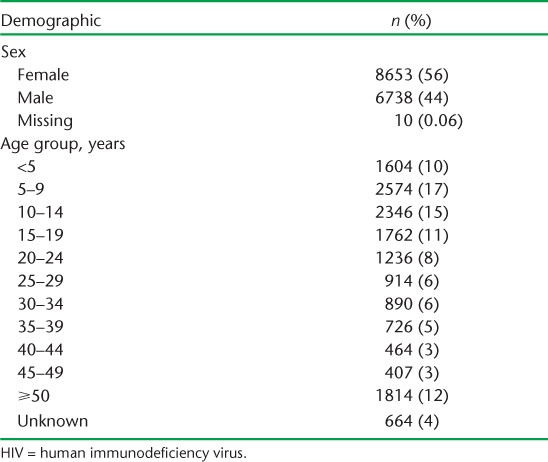

Through DtD visits, 16 200 individuals were enumerated for the project. Households where no members were home during the testing window or those who did not make themselves known after two visits could not be enumerated and were therefore not included in the study population. Table 1 describes the demographic characteristics of the 15 401 individuals eligible for testing.

TABLE 1.

Demographics of individuals eligible for door-to-door HIV testing services

DtD-HTS uptake

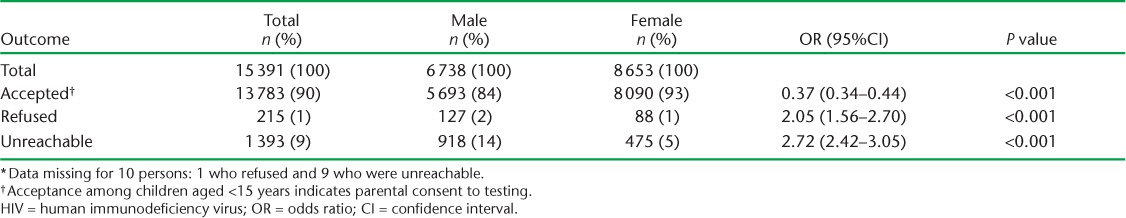

Of all eligible clients, 90% (13 783) accepted DtD-HTS, 1% (215) refused and 9% (1393) were unreachable. Table 2 details HTS uptake by sex. Sex analysis revealed that males were more than twice as likely to refuse HIV testing (OR 2.05, 95% confidence interval [CI] (1.56–2.70), P < 0.001) and almost three times more likely to be unreachable during DtD-HTS (OR 2.72, 95%CI 2.42–3.05, P < 0.001), although an overall male-to-female ratio of 1:1.4 was achieved among those tested. Age analysis showed a high level of acceptance among all age groups, of >90%.

TABLE 2.

Door-to-door HIV testing services uptake by sex *

HTS outcomes

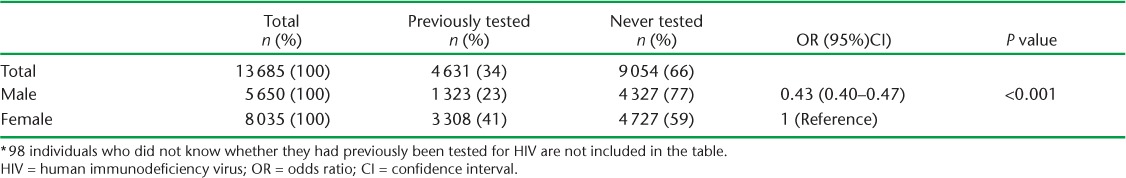

For those who were tested for HIV, a high proportion (66%) were first-time testers, with males less than half as likely to have previously been tested for HIV (OR 0.43, 95%CI 0.40–0.47, P < 0.001); 77% of males were first-time testers compared with 59% of females (Table 3). The average age of those who had been tested previously was 34 years, compared with an average age of 17 years for those who had not. Furthermore, 94% of children aged <15 years, 52% of young people aged 15–24 years and 38% of adults aged ⩾25 years had never been tested for HIV.

TABLE 3.

Individuals previously tested for HIV *

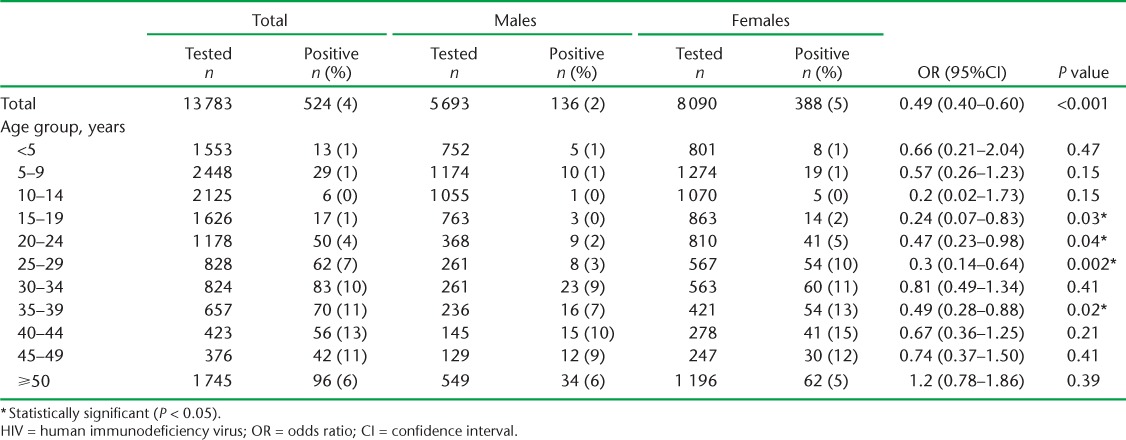

Table 4 shows age group and sex analyses for those individuals who tested positive for HIV. Overall 4% (n = 524) tested positive (females 5%, males 2%); males were half as likely to test positive (OR 0.49, 95%CI 0.40–0.60, P < 0.001). For those aged ⩾20 years, the positivity yield rate was much higher, at 6% for men and 8% for women. Men and women aged 40–44 years had the highest HIV positivity rates, at respectively 10% and 15%. There was no statistically significant difference in prevalence rates for males and females until the age group 15–19 years, after which males were only a quarter as likely to be HIV-positive (OR 0.24, 95%CI 0.07–0.83), P < 0.03). Females were more likely to be HIV-positive until the age of 30 years, when positivity rates for males approached those of females.

TABLE 4.

HIV positivity by sex and age group

DISCUSSION

Current efforts to target young people and men for HIV testing may not be sufficient to achieve the first 90% of the UNAIDS 90–90–90 targets, and more emphasis and financial support is needed to be able to target these groups successfully. DtD-HTS results in Mulanje District, Malawi, show that high acceptance among men, women and children can be achieved through community-based efforts, and by providing a convenient and confidential space for testing.

As young people aged ⩾15 years represented 43% of those identified as living in the target villages and 46% of those tested, it is clear that DtD-HTS can successfully reach this population. DtD-HTS and other HTS programs targeting young people should ensure, however, that they account for school schedules, which may have impacted the availability of those aged 10–19 years. While the HIV positivity yield among children aged <15 years was low (1%), the high rate of first-time testers in this group points to three important lessons learned. First, 49 HIV-positive children, who had likely been missed from prevention of mother-to-child transmission care, were identified and connected to care. These children were at risk of late treatment initiation and poorer treatment outcomes. Malawi has acknowledged the problem of children who ‘slip through the cracks’, evidenced by the 42% ART coverage for children aged <15 years compared to 71% for adults.14 Second, DtD-HTS introduces individuals to routine HIV testing at a young age, which may normalize the testing process and help them to adopt testing as a preventive health habit. Third, DtD-HTS provides an opportunity to educate young people about HIV prevention and treatment in an effort to reduce new infections as these individuals become sexually active and are at increased risk for HIV.

Adolescents and young people, especially girls aged 15–24 years, are a particularly important demographic to target for HIV screening and prevention to end the epidemic.15 A 2016 Lancet study showed that female adolescents and young people in South Africa are at much higher risk for contracting HIV than their male peers; this is largely due to having older male sexual partners with higher rates of HIV.16 Our study found comparable rates of HIV infection for males and females up to the age of 15 years, when females become four times as likely to be HIV-positive. Females aged 15–24 years represented 12% of all of those tested—this age group represents 7.8% of the general population—and more than one half of them had never been tested for HIV.17 This highlights the potential for the DtD-HTS approach in reaching this vulnerable population.

The high male-to-female ratio among those accepting HTS shows that DtD-HTS can be an important tool for reaching sexual equity in testing. Our data show that if men aged 25–49 years can be reached at their homes, they are equally as likely to be tested as women in the same age group, achieving higher equity than through the GAIA weekday mobile outreach clinics and facility-based testing in Mulanje District.18,19 The high rate of first-time testing among men (77%) indicates that HTS programs offered in the community may be a useful tool for achieving the first 90% of the 90–90–90 treatment targets.

While our study found that both men and women aged 35–49 years had the highest HIV-positive rates, this population represented only 10% of all those tested, whereas this age group represents 11.2% of the general population.17 To test those with the highest rates of HIV, programs need to target those at highest risk by offering testing at convenient hours, including weekends and evenings, to serve those who work outside the home. Uptake of HTS was higher than anticipated, and compared favorably with (or better than) rates achieved in other studies in the region (69–89% acceptance).20–22 We believe that GAIA's reputation as a trusted service provider in the community, together with the support received from the local chiefs and village leaders who encouraged their villagers to take advantage of the testing, were critical factors in the success of the project.

Limitations and strengths

The limitations of this study were the inability of the project to provide weekend and weeknight testing, which may have negatively impacted the number of young people and men reached. GAIA currently provides special weekend events to test young people and males in an overlapping geographical area, and as such some of those missed through DtD-HTS may have been reached at those events, impacting our results. Another limitation is that villagers residing in the target villages may have purposely left their homes or not presented to our team of testers during the intervention as a non-confrontational way of refusing testing, and as they could not be enumerated our acceptance rate may be overstated. In addition, the limited information on referral for treatment prevents the study from providing information on the impact of DtD-HTS on treatment enrollment, the second 90% of the 90–90–90 targets. Further research should examine linkage to and enrollment in care as Malawi moves to test and treat, and hones ART linkage and retention protocols.

The strengths of this study were its focus on a high prevalence population in a rural area, adherence to the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for observational research, the large population analyzed, and minimal missing or unknown data.23

CONCLUSIONS

DtD-HTS can be an effective way to reach populations in remote, rural high-prevalence areas where access to fixed testing sites is problematic. It overcomes many barriers by normalizing testing, it has more potential than facility-based testing or other community strategies to reach young people and men who may not otherwise be tested, and it can help identify young HIV-positive children who may have been missed by other methods. Using a trusted provider and taking care to achieve community support can ensure success in DtD-HTS efforts.

Acknowledgments

The GAIA DtD-HTS program has been funded by the Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation (Beverly Hills, CA, USA) since its inception in September 2015. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

References

- 1. Maheswaran H, Petrou S, MacPherson P, . et al. Cost and quality of life analysis of HIV self-testing and facility-based HIV testing and counselling in Blantyre, Malawi. BMC Med 2016; 14: 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dovel K, Yeatman S, Watkins S, Poulin M.. Men's heightened risk of AIDS-related death: the legacy of gendered HIV testing and treatment strategies. AIDS 2015; 29: 1123– 1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Skovdal M, Campbell C, Madanhire C, Mupambireyi Z, Nyamukapa C, Gregson S.. Masculinity as a barrier to men's use of HIV services in Zimbabwe. Global Health 2011; 7: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baker P, Dworkin S L, Tong S, Banks I, Shand T.. The men's health gap: men must be included in the global health equity agenda. Bull World Health Organ 2014; 92: 618– 620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Malawi National Statistical Office. . Malawi demographic and health survey key indicators report 2015–2016. Zomba, Malawi: NSO, 2016. http://sphfm.medcol.mw/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/DHS-Malawi-2015-16-key-indicators.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. . Global AIDS Update 2016. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS, 2016. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/global-AIDS-update-2016_en.pdf Accessed May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Angotti N, Bula A, Gaydosh L, Kimchi E Z, Thornton R L, Yeatman S E.. Increasing the acceptability of HIV counseling and testing with three C's: convenience, confidentiality and credibility. Soc Sci Med 2009; 68: 2263– 2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Govindasamy D, Ferrand R A, Wilmore S M, . et al. Uptake and yield of HIV testing and counselling among children and adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc 2015; 18: 20182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Labhardt N D, Motlomelo M, Cerutti B, . et al. Home-based versus mobile clinic HIV testing and counseling in rural Lesotho: a cluster-randomized trial. PLOS Med 2014; 11: e1001768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Osoti A O, John-Stewart G, Kiarie J N, . et al. Home-based HIV testing for men preferred over clinic-based testing by pregnant women and their male partners, a nested cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 2015; 15: 298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Bank. . Data: Malawi. Washington, USA: World Bank, 2016. http://data.worldbank.org/country/malawi Accessed October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Malawi National Statistical Office. . Malawi demographic and health survey 2010. Zomba, Malawi: NSO, 2011. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR247/FR247.pdf Accessed May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Malawi Ministry of Health. . Malawi comprehensive HIV testing and counselling training: participant handbook. Lilongwe, Malawi: MoH, 2013. http://hivstar.lshtm.ac.uk/files/2016/06/Malawi-Comprehensive-HIV-Testing-and-Counselling-Training2013.compressed.pdf Accessed May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Malawi Ministry of Health. . Government of Malawi integrated HIV program report April–June 2016. Lilongwe, Malawi: MoH, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15. de Oliveira T, Kharsany A B, Gräf T, . et al. Transmission networks and risk of HIV infection in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: a community-wide phylogenetic study. Lancet HIV 2016; 4: e41– e50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chamie G, Clark T D, Kabami J, . et al. A hybrid mobile approach for population-wide HIV testing in rural east Africa: an observational study. Lancet HIV 2016; 3: e111– e119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. National Malaria Control Programme. . Malawi malaria indicator survey 2014. Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Health, 2015. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/MIS18/MIS18.pdf Accessed May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Geoffroy E, Harries A D, Bissell K, . et al. Bringing care to the community: expanding access to health care in rural Malawi through mobile health clinics. PHA 2014; 4: 252– 258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Helleringer S, Mkandawire J, Reniers G, Kalilani-Phiri L, Kohler H-P.. Should home-based HIV testing and counseling services be offered periodically in programs of ARV treatment as prevention? A case study in Likoma (Malawi). AIDS Behav 2013; 17: 2100– 2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dalal W, Feikin D R, Amolloh M, . et al. Home-based HIV testing and counseling in rural and urban Kenyan communities. J AIDS 2013; 62: e47– e54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Doherty T, Tabana H, Jackson D, . et al. Effect of home based HIV counselling and testing intervention in rural South Africa: cluster randomised trial. BMJ 2013; 346: 3481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Naik R, Tabana H, Doherty T, . et al. Client characteristics and acceptability of a home-based HIV counselling and testing intervention in rural South Africa. BMC Public Health 2012; 12: 824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. von Elm E, Altman D G, Egger M, . et al. STrengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007; 370: 1453– 1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]