Abstract

We sought to identify relationship and individual psychological factors that related to four profiles of intimate partner violence (IPV) among pregnant adolescent couples: no IPV, male IPV victim only, female IPV victim only, mutual IPV, and how associations differ by sex. Using data from a longitudinal study of pregnant adolescents and partners (n = 291 couples), we used a multivariate profile analysis using multivariate analysis of covariance with between and within-subjects effects to compare IPV groups and sex on relationship and psychological factors. Analyses were conducted at the couple level, with IPV groups as a between-subjects couple level variable and sex as a within-subjects variable that allowed us to model and compare the outcomes of both partners while controlling for the correlated nature of the data. Analyses controlled for age, race, income, relationship duration, and gestational age. Among couples, 64% had no IPV; 23% male IPV victim only; 7% mutual IPV; 5% female IPV victim only. Relationship (F = 3.61, P < .001) and psychological (F = 3.17, P < .001) factors differed by IPV group, overall. Attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance, relationship equity, perceived partner infidelity, depression, stress, and hostility each differed by IPV profile (all P < .01). Attachment anxiety, equity, depression and stress had a significant IPV profile by sex interaction (all P < .05). Couples with mutual IPV had the least healthy relationship and psychological characteristics; couples with no IPV had the healthiest characteristics. Females in mutually violent relationships were at particularly high risk. Couple-level interventions focused on relational issues might protect young families from developing IPV behaviors.

Keywords: pregnancy in adolescence, adolescent couples, partner violence, female perpetration, mutual violence

INTRODUCTION

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is pervasive in the United States, with an estimated 4.7 million women and 5.4 million men victimized yearly at a cost to health systems of $2.3 billion to $7.0 billion (Black et al., 2011; Brown, Finkelstein, & Mercy, 2008). Young couples are at particular risk for IPV (Capaldi, Knoble, Shortt, & Kim, 2012). Nearly 70% of female IPV victims have their first IPV experience before the age of 25 years, and 22.4% are first victimized before the age of 18 years (Black et al., 2011). Between 6% and 57% of adolescents report having experienced IPV victimization in studies, with higher prevalence reported among socioeconomically disadvantaged populations (Capaldi & Gorman-Smith, 2003; Hickman, Jaycox, & Aronoff, 2004; Teitelman, Ratcliffe, Morales-Aleman, & Sullivan, 2008).

Teens who experience IPV are more likely to become pregnant (Miller et al., 2010). Adolescents who have had babies exhibit more partner conflict than other adolescent couples, and later in adulthood report a history of more abusive relationships than their peers (Florsheim et al., 2003; Moffitt & E-Risk Study Team, 2002). Further, pregnant adolescents are at higher risk of IPV than older mothers (Lipsky, Holt, Easterling, & Critchlow, 2005; Moffitt & E-Risk Study Team, 2002) and face adverse perinatal consequences (Bailey & Daugherty, 2007; Sarkar, 2008). IPV rates may be particularly high among pregnant and parenting adolescent couples because the transition to parenthood tends to be stressful. Parenting may be more stressful for adolescent couples than adults, as they tend to have fewer resources and are simultaneously negotiating the developmental tasks of adolescence (Cowan & Cowan, 2000).

Historically, IPV research and intervention has been based on a “male aggressor—female victim” paradigm (Goldenson, Geffner, Foster, & Clipson, 2007). However, research over the past 30 years, including more than 200 studies with data from males and females, containing nationally representative samples of US couples, as well as Canadian and UK national crime surveys, indicate that women perpetrate acts of violence against intimate partners at similar rates as men (Archer, 2000; Straus, 2011); however, women are more likely to suffer severe physical violence and adverse consequences from IPV (e.g., PTSD, injury) than men (Black et al., 2011).

Adolescent couples tend to be mutually violent and there is considerable variability in the patterns of violence among young couples (Hickman et al., 2004). Research has focused primarily on one type of IPV among expectant adolescent couples: female victimization by male partners. Many scholars have noted the importance of examining IPV as a heterogeneous phenomenon to better understand the risks associated with different types of IPV; to more accurately assess for IPV; and to match people with the most appropriate interventions (Capaldi & Kim, 2007; Cavanaugh & Gelles, 2005; Kelly & Johnson, 2008). Researchers have begun to focus on the heterogeneity of IPV specific to adolescent couples (Paradis, Hébert, & Fernet, 2015; Reidy et al., 2016). We examine four profiles of IPV in the relationships of expectant adolescent couples: no IPV, female IPV victim only, male IPV victim only, and mutual IPV.

Research on IPV during pregnancy has focused primarily on individual-level differences between those with and without IPV present, but has not taken an ecological approach to examine the characteristics of couples with divergent IPV profiles. Few studies have included both members of a couple in analyses. Dyadic analyses of IPV suggest relational and individual-level factors associated with IPV can vary by sex (Karakurt & Cumbie, 2012; Marshall, Jones, & Feinberg, 2011). Using correlates of IPV identified in previous literature, we examine how multi-level (i.e., relational, individual) characteristics relate to IPV profile for expectant adolescent couples, and how these vary by sex.

Key demographic characteristics associated with IPV include age, race/ethnicity, sex, and socioeconomic status (Capaldi et al., 2012). IPV risk tends to decline over time, with younger women at higher risk (Kim, Laurent, Capaldi, & Feingold, 2008). Women and men tend to perpetrate IPV at similar rates; however, at younger ages, women perpetrate more often than men (Capaldi, Kim, & Shortt, 2007). Low income and unemployment are fairly robust socioeconomic risk factors for IPV compared to educational level, which has mixed findings (Capaldi et al., 2012). Race and ethnicity have been cited as a risk factor for IPV in several large nationally representative datasets (Black et al., 2011; Capaldi et al., 2012).

IPV—like adolescent pregnancy—is the outcome of an interpersonal interaction. Thus, it is critical to consider relationship-level correlates of IPV. However, few studies have systematically examined relationship factors associated with different IPV profiles, and few studies include both members of a couple in their analyses. IPV perpetration and victimization have been associated with women’s and men’s romantic attachment anxiety, romantic attachment avoidance, and a mismatch of avoidant and anxious attachment styles for partners (Doumas, Pearson, Elgin, & McKinley, 2008; Lawson & Brossart, 2013; Macke, 2011; Orcutt, Garcia, & Pickett, 2005). Inequality in relationships—and between sexes—has been linked to IPV (Davies, Ford-Gilboe, & Hammerton, 2009; Gomez, Speizer, & Moracco, 2011; Gressard, Swahn, & Tharp, 2015; Lawoko, Dalal, Jiayou, & Jansson, 2007). Perceived partner infidelity has been consistently associated with physical IPV and IPV severity (Arnocky, Sunderani, Gomes, & Vaillancourt, 2015; Nemeth, Bonomi, Lee, & Ludwin, 2012).

Individual psychological characteristics, such as depression, stress, hostility, and gender norms have been identified as significantly related to IPV (Capaldi et al., 2012). Depression has been consistently linked to IPV victimization for women and perpetration for men (Lacey, McPherson, Samuel, Powell Sears, & Head, 2013; Stith, Smith, Penn, Ward, & Tritt, 2004), including during pregnancy and postpartum (Valentine et al., 2011). Some research has also found that female IPV perpetration, male IPV victimization, and mutual IPV are associated with depression, and have suggested potential differences by gender and IPV profile (Graham, Bernards, Flynn, Tremblay, & Wells, 2012). Stress has received less attention, yet various types of stress have been found to predict IPV, including financial stress, community stress, parenting stress, work stress, life stress, and acculturation stress (Capaldi et al., 2012). Hostility and negative emotionality have been associated with IPV perpetration in several studies (Moffitt, Krueger, Caspi, & Fagan, 2000; White & Widom, 2003), and particularly for men (Norlander & Eckhardt, 2005). Hostile cognitions, hostile attributions, and hostile talk about women have been found to predict male IPV perpetration (Capaldi et al., 2012). Traditional masculine gender role ideology and conformity—including aggressiveness and suppression of emotional vulnerability (Oringher & Samuelson, 2011)—have been associated with IPV perpetration behavior for men (Santana et al., 2006). Masculine role norm identification has been associated with perpetration of psychological IPV for both men and women (Próspero, 2008).

In this paper, we seek to identify relational and individual-level psychological factors that relate to various IPV profiles among pregnant adolescent couples (i.e., no IPV, female IPV victim only, male IPV victim only, mutual IPV). Further, we explicitly examine how the associations differ based on sex. By examining the multi-level (i.e., relational, individual) characteristics of couples with divergent IPV profiles, and including both partners in our analyses, we can begin to understand complex patterns of IPV and help inform the development of interventions for pregnant adolescent couples. Pregnant adolescent couples are at high risk for IPV, but could be accessible for intervention through their frequent interface with the medical system during pregnancy. Changes made during this critical time in family development could have a broad impact on IPV incidence and family health.

METHODS

Study Sample and Procedures

These data come from a longitudinal study of pregnant adolescent females and their male partners. Between July 2007 and February 2011, 296 pregnant adolescents and their male partners (592 total participants) were recruited from obstetric clinics and an ultrasound clinic at four university-affiliated hospitals in Connecticut. Research staff screened potential participants for eligibility, explained the study in detail, and answered questions. If the baby’s father was not present during screening, staff requested permission to contact him to explain the study, provided informational materials, and asked the potential participant to discuss the study with her partner.

Inclusion criteria included: (i) female in the second or third trimester of pregnancy at time of baseline interview; (ii) female between 14 and 21 years and male at least 14 years at time of the baseline interview; (iii) members of the couple report being in a romantic relationship with one another; (iv) both report being the biological parents of the unborn baby; (v) both agree to participate; and (vi) both speak English or Spanish. To be eligible for this longitudinal study, an initial run-in period required that participants were able to be re-contacted before their due date.

Written informed consent was obtained by research staff at baseline. Separately, but simultaneously, couples completed structured interviews via audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI). Participation was voluntary, confidential, and did not influence the provision of care or services. All procedures were approved by Institutional Review Boards at Yale University and study clinics. Participants were reimbursed $25 for each interview.

Of 413 eligible couples, 296 (72.2%) couples enrolled in the study. Couples who agreed to participate were of greater gestational age (P = .03). Participation did not vary by any other screened demographic characteristic (all P >.05). Data reported are from baseline assessments. These baseline interviews took place in the 3rd trimester of pregnancy (M = 29 weeks gestation). Five couples had missing data on violence measures resulting in a final sample of 291 couples.

Measures

IPV was assessed using a modified version of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996). Specifically, participants reported whether they “have ever been shoved, punched, hit, slapped, or physically hurt” by their current partner to assess physical IPV, and whether their partner “ever used force (hitting, holding down, using a weapon) to make [them] have sex (vaginal, oral, or anal sex) with him/her” to assess sexual IPV. If neither partner reported physical or sexual IPV victimization, their relationship was categorized as experiencing “no IPV.” If the male partner reported either type of IPV victimization and the female partner reported neither type of IPV victimization, their relationship was categorized as “male IPV victim only.” If the female partner reported either type of IPV victimization and the male partner reported neither type of IPV victimization, their relationship was categorized as “female IPV victim only.” If both partners reported either type of IPV victimization, their relationship was categorized as having “mutual IPV.”

Demographics included sex, age (years), race (African–American, Hispanic, White, Other), relationship duration (months), parity, and gestational age.

Relationship Factors

Romantic Attachment Avoidance and Romantic Attachment Anxiety were assessed using the 36-item Experiences in Close Relationships Inventory (Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998). Participants responded to relationship statements on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = disagree strongly to 7 = agree strongly to statements such as, “I worry about being alone” and “I try to avoid getting too close to my partner.” Both scales consisted of 18 items. Items were summed for separate attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety scores. Internal consistency was very good for both avoidance (α = .85) and anxiety subscales (α = .89).

Relationship equity was assessed with a 21-item scale adapted from the Family Responsibility Index (Traupmann, Petersen, Utne, & Hatfield, 1981). Participants rated who contributes more to the relationship in various ways, like “responsiveness to each other’s needs,” “paying for things,” “intelligence,” “physical attractiveness,” and “making decisions that affect both of you” on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 = My partner contributes much more than I do to 5 = I contribute much more than my partner does. The equity score was a count of items answered as “My partner and I contribute equally.” Internal consistency was very good (α = .87).

Perceived partner infidelity was measured using a single item that asked “Did the father/mother of your baby ever have sexual intercourse with someone else during the time you have been in a relationship with the father/mother of your baby?” Respondents answered on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 = definitely no to 5 = definitely yes.

Psychological Factors

Depression symptoms were assessed using a 15-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D), adapted to remove somatic symptoms affected by pregnancy, for example, sleeping (Radloff, 1977). For each symptom of depression (e.g., “I had crying spells”), participants indicated frequency of thoughts or behaviors on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 = less than one day in the last week to 4 = 5–7 days in the last week. Items were summed for a total score. This measure had good internal consistency (α = .82).

Stress was assessed using the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen & Williamson, 1988). Participants indicated how often in the past month they had stressful feelings and thoughts (e.g., “nervous and stressed”) on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 = never to 4 = very often. Items were summed for a total score. This measure had adequate internal consistency (α = .76).

Hostility was measured using 5 items from the Brief Symptom Inventory that asked how much they were bothered by hostile feelings (e.g., “temper outbursts that you could not control”) within the past 7 days (Derogatis, 1993). Responses ranged from 1 = not at all to 5 = extremely. Items were summed for a total score. This measure had good internal consistency (α = .87).

Toughness Masculinity Norm was measured using the 8-item Toughness subscale of the Masculine Role Norm Scale (Thompson & Pleck, 1986). Respondents indicated agreement with belief statements about men’s behavior (e.g., “When a man is feeling a little pain he should try not to let it show very much”) on a 7-point scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. Items were summed. This measure had adequate internal consistency (α = .74).

Data Analysis

We used a multivariate profile analysis using multivariate analysis of covariance with between and within-subjects effects to compare IPV groups and sex on relationship and psychological factors. Analyses were conducted at the couple level (N = 291 couples), with IPV groups as a between-subjects couple level variable and sex as a within-subjects variable that allowed us to model and compare the outcomes of both male and female partners while controlling for the correlated nature of the data. Outcome variables were grouped based on conceptual similarity into two groups such that two overall multivariate analyses were conducted: (i) relationship (i.e., attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance, relationship equity, perceived partner infidelity), (ii) psychological (i.e., depression, stress, hostility, and toughness masculinity norm). In cases where the multivariate analyses were significant, follow-up univariate tests were conducted to assess the nature of the differences. Two effects were assessed for each multivariate analysis: IPV group (which assessed the differences between the four violence groups on outcomes across both members of the couple), and IPV group by sex (which assessed whether the profiles of outcomes between IPV groups differ by sex). Significant effects were followed up by post-hoc or simple effects to assess the nature of the differences. All analyses controlled for age, race, income, length of relationship, and gestational age.

RESULTS

Demographic Factors

The majority of participants were Black (44%) or Latina/o (38%). The mean age was 18.7 years (SD = 1.7) for women and 21.3 years (SD = 4.1) for men. Mean gestational age was 29.1 weeks, and mean length of relationship for couples was 2 years and 3 months. There were no significant differences on any of the demographic factors for violence groups. Among couples, 64% reported no IPV, 23% reported male IPV victim only, 7% reported mutual IPV, and 5% reported female IPV victim only. IPV profile of couples was not related to age, income, parity, or education. Demographic characteristics by IPV profile by sex are presented in Table I.

TABLE I.

Demographics by IPV Group

| No Violence (n = 186)

|

Male Victim (n = 68)

|

Female Victim (n = 16)

|

Mutual Violence (n = 21)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) |

| Age | ||||

| Male | 21.6 (4.2) | 20.8 (3.4) | 21.9 (3.7) | 19.8 (2.6) |

| Female | 18.8 (1.6) | 18.7 (1.7) | 19.3 (1.4) | 18.1 (1.5) |

| Income | ||||

| Male | $11,362 ($11,395) | $9,794 ($12,858) | $10,469 ($8,908) | $9,786 ($14,277) |

| Female | $6,148 (7,538) | $4,662 ($6,228) | $5,625 ($5,439) | $6,881 ($10,340) |

| Paritya | ||||

| Male | .29 (.60) | .40 (.74) | .50 (.89) | .24 (.54) |

| Female | .26 (.53) | .22 (.45) | .31 (.60) | .14 (.36) |

| Education | ||||

| Male | 11.9 (2.0) | 11.9 (1.6) | 12.4 (1.8) | 11.7 (1.7) |

| Female | 11.8 (1.9) | 11.6 (1.6) | 12.1 (1.5) | 11.9 (2.4) |

Mean number of previous live births.

Relationship Factors

Relationship factors significantly differed by IPV group, overall (F = 3.61, P < .001). Attachment anxiety (F = 8.32, P < .001), attachment avoidance (F = 4.64, P = .004), relationship equity (F = 15.21, P < .001), and perceived partner infidelity (F = 8.85, P < .001) each significantly differed by IPV profile (Table II). Relationships characterized by mutual IPV had the highest attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance, the least relationship equity, and the highest perceived partner infidelity, whereas relationships with no IPV reported the lowest attachment anxiety and avoidance, the most equity, and the lowest perceived partner infidelity. See Table III.

TABLE II.

Intimate Partner Violence Groups and Relationship and Psychological Factors, Overall and by Sex

| No Violence (n = 186)

|

Male Victim (n = 68)

|

Female Victim (n = 16)

|

Mutual Violence (n = 21)

|

Violence Group | Violence Group × Sex | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| Relationship factors | F = 3.61, P < .001** | F = 3.21, P < .001** | ||||

| Attachment anxiety | ||||||

| Male | 53.97 (18.55) | 60.81 (19.70) | 53.31 (17.10) | 56.05 (17.65) | F = 8.32, P < .001** | F = 5.66, P = .001** |

| Female | 57.26 (19.35) | 61.85 (23.72) | 74.75 (22.82) | 81.71 (18.10) | ||

| Attachment avoidance | ||||||

| Male | 47.27 (15.78) | 50.41 (16.40) | 53.00 (15.29) | 54.10 (22.70) | F = 4.64, P = .004** | F = .20, P = .897 |

| Female | 44.42 (14.77) | 48.21 (16.41) | 54.00 (16.11) | 52.48 (19.86) | ||

| Equity | ||||||

| Male | 66.88 (26.92) | 54.09 (26.28) | 64.72 (26.32) | 45.45 (26.34) | F = 15.21, P < .001** | F = 5.69, P = .001** |

| Female | 66.33 (23.99) | 60.74 (24.43) | 35.00 (18.08) | 38.31 (21.45) | ||

| Perceived partner infidelity | ||||||

| Male | 1.64 (1.15) | 2.26 (1.53) | 1.75 (1.39) | 2.10 (1.38) | F = 8.85, P < .001** | F = 2.37, P = .071 |

| Female | 1.71 (1.27) | 2.37 (1.69) | 2.62 (1.96) | 2.81 (1.78) | ||

| Psychological factors | F = 3.17, P < .001** | F = 2.06, P = .006** | ||||

| Depression | ||||||

| Male | 7.85 (5.60) | 10.64 (7.86) | 7.56 (5.06) | 9.62 (6.70) | F = 7.71, P < .001** | F = 3.52, P = .016** |

| Female | 9.19 (6.59) | 11.76 (8.08) | 13.63 (6.23) | 16.33 (9.15) | ||

| Stress | ||||||

| Male | 14.23 (5.90) | 17.51 (6.73) | 14.31 (5.76) | 18.62 (5.43) | F = 10.44, P < .001** | F = 4.06, P = .008** |

| Female | 15.68 (5.90) | 17.18 (5.85) | 21.19 (7.16) | 21.33 (6.04) | ||

| Hostility | ||||||

| Male | 9.01 (4.68) | 11.04 (5.12) | 8.06 (3.71) | 12.57 (5.24) | F = 9.37, P < .001** | F = .70, P = .556 |

| Female | 9.59 (4.11) | 11.13 (5.19) | 10.43 (4.83) | 13.52 (5.01) | ||

| Masculine toughness norm | ||||||

| Male | 34.16 (8.82) | 34.52 (9.78) | 33.13 (6.76) | 38.10 (8.31) | F = 1.62, P = .185 | F = 2.52, P = .059 |

| Female | 27.59 (7.30) | 26.60 (8.31) | 32.19 (6.56) | 28.00 (6.34) |

Note: All analyses control for age, race, income, length of relationship and gestational age.

P < .05,

P < .01.

TABLE III.

Intimate Partner Violence Groups (Pairwise Comparisons)

| Mean (SE) | Male Victim (P) | Female Victim (P) | Mutual Violence (P) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attachment anxiety | ||||

| No violence | 55.57 (1.03) | .004** | .030* | .000** |

| Male victim | 61.51 (1.73) | .604 | .035* | |

| Female victim | 63.55 (3.51) | .241 | ||

| Mutual violence | 69.08 (3.10) | |||

| Attachment avoidance | ||||

| No violence | 45.88 (.91) | .090 | .025* | .003** |

| Male victim | 48.94 (1.53) | .223 | .081 | |

| Female victim | 53.19 (3.11) | .761 | ||

| Mutual violence | 54.46 (2.75) | |||

| Equity | ||||

| No violence | 66.79 (1.43) | .001** | .001** | .000** |

| Male victim | 57.11 (2.40) | .217 | .001** | |

| Female victim | 50.37 (4.87) | .146 | ||

| Mutual violence | 40.84 (4.30) | |||

| Perceived partner infidelity | ||||

| No violence | 1.67 (.08) | .000** | .083 | .000** |

| Male victim | 2.28 (.13) | .682 | .234 | |

| Female victim | 2.16 (.27) | .215 | ||

| Mutual violence | 2.61 (.24) | |||

| Depression symptoms | ||||

| No violence | 8.57 (.38) | .002** | .152 | < .001** |

| Male victim | 10.97 (.64) | .751 | .072 | |

| Female victim | 10.51 (1.29) | .103 | ||

| Mutual violence | 13.34 (1.14) | |||

| Stress | ||||

| No violence | 15.00 (.35) | .002** | .032* | < .001** |

| Male victim | 17.11 (.59) | .674 | .007** | |

| Female victim | 17.67 (1.19) | .091 | ||

| Mutual violence | 20.37 (1.05) | |||

| Hostility | ||||

| No violence | 9.33 (.26) | .002** | .911 | < .001** |

| Male victim | 10.95 (.44) | .087 | .014* | |

| Female victim | 9.23 (.90) | .001** | ||

| Mutual violence | 13.21 (.79) | |||

| Masculine toughness norm | ||||

| No violence | 30.91 (.45) | .543 | .269 | .092 |

| Male victim | 30.38 (.75) | .180 | .059 | |

| Female victim | 32.66 (1.52) | .753 | ||

| Mutual violence | 33.30 (1.34) | |||

Note: All analyses control for age, race, income, length of relationship and gestational age.

P < .05,

P < .01.

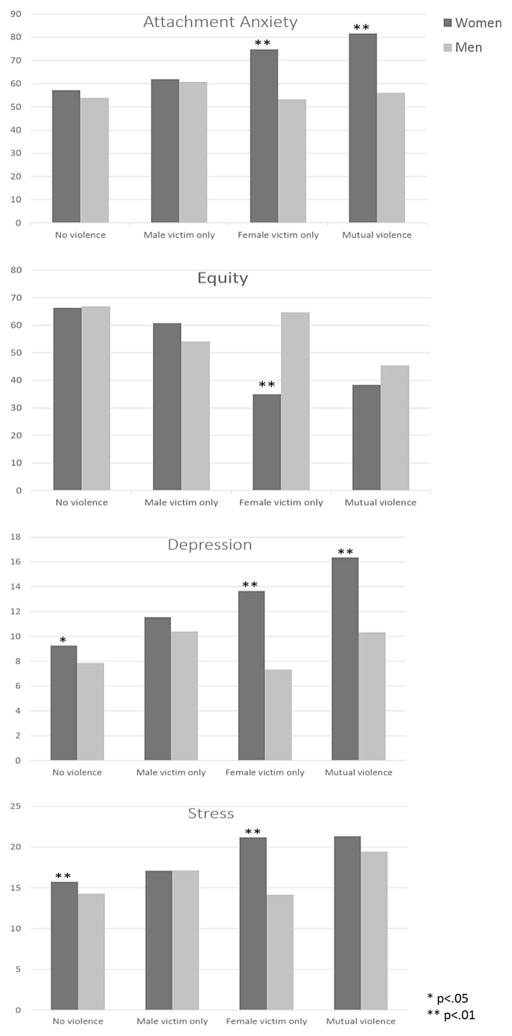

Additionally, significant IPV by sex differences emerged for relationship factors, overall (F = 3.21, P < .001). Univariate analyses showed that the relationship between attachment anxiety and IPV group differed significantly by sex (F = 5.66, P = .001). Men were more likely to be anxiously attached in relationships in which there was a male IPV victim only and least likely to be anxiously attached when there was a female IPV victim only. Women were most likely to be anxiously attached in relationships with mutual IPV or a female IPV victim only. See Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Sex differences in relationship and psychological factors by IPV type.

There was a significant IPV group by sex interaction for relationship equity (F = 5.69, P = .001). Both men and women in the no IPV group reported the most relationship equity (Fig. 1). Both men and women reported less relationship equity in IPV groups in which they were being victimized. However, for women, being in an IPV group in which they were being victimized was associated with much lower perceived relationship equity than for men, who reported the lowest equity in mutually violent relationships. Women reported the lowest level of relationship equity in relationships with a female IPV victim only.

Psychological Factors

Psychological factors significantly differed by IPV group, overall (F = 3.17, P < .001). Depression (F = 7.71, P < .001), stress (F = 10.44, P < .001), and hostility (F = 9.37, P < .001) each related to IPV group. Masculine toughness norm (F = 1.62, P = .185) did not relate to IPV group (Table II). Relationships with mutual IPV had the highest level of depressive symptoms, stress, and hostility, whereas relationships with no IPV reported the lowest levels. See Table III.

There was a significant IPV group by sex interaction overall for psychological factors (F = 2.06, P = .006). The relationship between depression and IPV group differed significantly by sex (F = 3.52, P = .016). Women experienced significantly higher levels of depression symptoms than men in every IPV group, except the male victim only group. Men’s depression symptoms were highest in the male IPV victim only group, followed by the mutual IPV group; men’s depression symptoms were lowest in the female IPV victim only group. Women’s depression symptoms were highest in the mutual IPV group, followed by the female victim only group, and lowest in relationships with no IPV (Fig. 1). Women in the no IPV group had significantly lower depression symptoms than all other groups, including male IPV victim only. Women’s depression symptoms in the mutual IPV group were significantly different from the no IPV and male IPV victim only, but not the female IPV victim only group.

The association between stress and IPV group differed significantly by sex (F = 4.06, P = .008). In the no IPV and female IPV victim only groups, women reported significantly higher stress than men. Both women and men reported the highest levels of stress in the mutual IPV group and the lowest levels in the no IPV group. Both reported higher stress in groups in which they were victimized and lower levels in groups in which they were not victimized (Fig. 1).

DISCUSSION

The majority of adolescent couples in this study did not experience violence in their relationships. Surprisingly, couples with a male IPV victim only were the most prevalent group experiencing IPV, followed by couples with mutual IPV, and finally couples with a female IPV victim only. A randomized controlled trial delivering a behavioral intervention with a similar study population (urban minority women in prenatal care) found that while male victimization was more common than female victimization, mutual IPV was most prevalent during pregnancy (Shneyderman & Kiely, 2013). That study included adults and thus more cohabitating couples; mutual violence is more common if cohabitating (Cui, Ueno, Gordon, & Fincham, 2013).

Couples with no IPV tended to have the healthiest relationship characteristics (i.e., less attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance, more relationship equity, and less perceived partner infidelity), and individual psychological characteristics (i.e., less depressive symptoms, stress, and hostility). These findings support the concept that healthier relationships and individuals are less likely to use violence during couple conflicts. Couples with mutual IPV tended to have the least healthy relationship and psychological characteristics. Far from being protective for women—or indicating equality between participants—our findings indicate that mutual IPV is associated with the worst relationship and psychological profiles, particularly for women.

As expected, women in relationships with a male IPV victim only tended to cite fewer adverse characteristics than men in relationships with a male IPV victim only, while men in relationships with a female IPV victim only tended to cite fewer adverse characteristics than women in relationships with a female IPV victim only. However, there were sex differences in the factors related to IPV profiles. For women, depressive symptoms and stress were higher than men’s overall, and were increased with any type of IPV, including their perpetration. Previous research on the relation between female perpetration and depressive symptoms for women are mixed (Milan, Lewis, Ethier, Kershaw, & Ickovics, 2005; Sullivan, Meese, Swan, Mazure, & Snow, 2005). Men’s depressive symptoms and stress were only higher when they were in IPV groups in which they were victimized. For men, depressive symptoms and stress were lowest in relationships with no IPV or a female IPV victim only. Results suggest that the psychological characteristics of men and women in relationships with various IPV profiles are different and should be considered separately when addressing IPV in relationships.

Women in mutually violent relationships had significantly higher attachment anxiety. Previous literature has found insecure attachment to be related to mutual violence and perpetration for both women and men (Lawson & Brossart, 2013). In this sample, women in relationships characterized by any violence against them (mutual or unilateral) were much more likely to be anxiously attached. Not so for men. Young women who are anxiously attached to their partner may try to maintain relationships by tolerating or joining in violence.

Women and men reported the highest levels of relationship equity in relationships in which they, personally, were not being victimized. Both women and men reported low equity in relationships in with mutual IPV. This could support a family systems/control balance explanation of IPV, whereby members of a couple may be using acts of violence to tip the scales of perceived inequity back in their favor (Smithey & Straus, 2004). When both men and women perceive inequity, there is mutual IPV. A shared perception of high equity relates to no IPV use.

Adolescent pregnancy can be a period of increased risk of IPV. Stressful life events increase violence, and pregnancy may change adolescent relationships and place additional expectations, stresses, and commitments on unprepared couples (Milan et al., 2005). This IPV can take several forms, which are differentially associated with relationship and psychological characteristics, and vary by sex (Graham et al., 2012). Adolescent women in mutually violent relationships may be most at risk (Burk & Seiffge-Krenke, 2015; Chiodo et al., 2012).

Both IPV and adolescent pregnancy occur in the context of a relationship. A relational orientation may be the most salient framework to consider IPV among pregnant adolescent couples struggling with mounting stresses, nascent relationship skills, and minimal conflict resolution proficiency. Couple interventions that consider the increased risk of injury to women, but recognize the existence of a dynamic in which both members may participate, may be most effective to reduce IPV (O’Leary & Slep, 2012; Wray, Hoyt, & Gerstle, 2013). Interventions with pregnant couples that focus on relational issues might better protect these nascent families from developing or escalating IPV behaviors during this vulnerable period.

This study had several limitations. First, analyses are cross-sectional; thus, the directionality of associations is unknown. Also, our measures do not assess the context of IPV, and further qualitative study could provide such context. Data were collected by self-report and are subject to measurement error, recall bias, and under-reporting of sensitive topics; however, we tried to minimize these issues using ACASI. Violence groups were uneven, with female victim only having the lowest representation. We did not address violence severity; mutually violent couples were not necessarily symmetrically violent. Participants were asked about IPV history with their current partner; the timeframe was not more specific than being within their current partnership (mean length of relationship was 27 months (SD = 20); there was no significant difference in relationship length by violence profile). We collected victimization and perpetration reports from each member of a couple, but relied on reports of victimization from each member of the couple to create the violence groups, as couples’ reports of victimization and perpetration are often discrepant (Archer, 1999; Wenger, 2015).

Despite limitations, this study has several strengths. We examined IPV during pregnancy, an important window of opportunity for prevention. Couples interact regularly with the health care system during pregnancy and are motivated to make behavioral changes in anticipation of parenthood (Bloch & Parascandola, 2014; Ickovics, Niccolai, Lewis, Kershaw, & Ethier, 2003; Lee et al., 2015). Relationship violence debuts early in teens’ dating experiences and predicts IPV during the adult years (Lindhorst & Oxford, 2008). Interrupting nascent relational patterns that contribute to IPV may prevent a trajectory of relationship violence and interrupt the inter-generational transmission of violence, yielding lasting consequences for individuals, couples, and families (Sutton, Simons, Wickrama, & Futris, 2014; Widom, Czaja, & Dutton, 2014).

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: National Institute of Mental Health; contract grant numbers: R01MH75685, 5P30MH062294.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Archer J. Assessment of the reliability of the conflict tactics scales: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Interpesonal Violence. 1999;14:1263–1289. [Google Scholar]

- Archer J. Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:651–680. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnocky S, Sunderani S, Gomes W, Vaillancourt T. Anticipated partner infidelity and men’s intimate partner violence: The mediating role of anxiety. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences. 2015;9:186–196. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey B, Daugherty R. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: Incidence and associated health behaviors in a rural population. Maternal & Child Health Journal. 2007;11:495–503. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0191-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black M, Basile K, Breiding M, Smith S, Walters M, Merrick M, … Stevens M. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch M, Parascandola M. Tobacco use in pregnancy: A window of opportunity for prevention. The Lancet Global Health. 2014;2:e489–e490. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70294-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR. Self-report measurement of adult romantic attachment: an integrative overview. In: Simposon JA, editor. Attachment theory and close relationships. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. pp. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- Brown D, Finkelstein E, Mercy J. Methods for estimating medical expenditures attributable to intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:1747–1766. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burk W, Seiffge-Krenke I. One-sided and mutually aggressive couples: Differences in attachment, conflict prevalence, and coping. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2015;50:254–266. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi D, Gorman-Smith D. The development of aggression in young male/female couples. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. pp. 243–278. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi D, Kim H. Typological approaches to violence in couples: A critique and alternative conceptual approach. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:253–265. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi D, Kim H, Shortt J. Observed initiation and reciprocity of physical aggression in young, at-risk couples. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:101–111. doi: 10.1007/s10896-007-9067-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi D, Knoble N, Shortt J, Kim H. A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:231–280. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh M, Gelles R. The utility of male domestic violence offender typologies: New directions for research, policy and practice. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20:155–166. doi: 10.1177/0886260504268763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiodo D, Crooks C, Wolfe D, McIsaac C, Hughes R, Jaffe P. Longitudinal prediction and concurrent functioning of adolescent girls demonstrating various profiles of dating violence and victimization. Prevention Science. 2012;13:350–359. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Williamson G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan S, Oskamp S, editors. The social psychology of health. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan C, Cowan P. When partners become parents: The big life change for couples. New York: Basic Books; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Ueno K, Gordon M, Fincham FD. The continuation of intimate partner violence from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2013;75:300–313. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies L, Ford-Gilboe M, Hammerton J. Gender inequality and patterns of abuse post leaving. Journal of Family Violence. 2009;24:27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis L. Brief symptom inventory (BSI): Administration, scoring and procedures manual. Minneapolis, MN: NCS Pearson; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Doumas D, Pearson C, Elgin J, McKinley L. Adult attachment as a risk factor for intimate partner violence: The “mispairing” of partners’ attachment styles. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:616–634. doi: 10.1177/0886260507313526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florsheim P, Sumida E, McCann C, Winstanley M, Fukui R, Seefeldt T, Moore D. The transition to parenthood among young African American and Latino couples: Relational predictors of risk for parental dysfunction. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:65–79. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenson J, Geffner R, Foster SL, Clipson CR. Female domestic violence offenders: Their attachment security, trauma symptoms, and personality organization. Violence and Victims. 2007;22:532–545. doi: 10.1891/088667007782312186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez AM, Speizer IS, Moracco KE. Linkages between gender equity and intimate partner violence among urban Brazilian youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;49:393–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, Bernards S, Flynn A, Tremblay P, Wells S. Does the relationship between depression and intimate partner aggression vary by gender, victim-perpetrator role, and aggression severity? Violence & Victims. 2012;27:730–743. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.27.5.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gressard L, Swahn M, Tharp A. A first look at gender inequality as a societal risk factor for dating violence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2015;49:448–457. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman L, Jaycox L, Aronoff J. Dating violence among adolescents: Prevalence, gender distribution, and prevention program effectiveness. Trauma Violence & Abuse. 2004;5:123–142. doi: 10.1177/1524838003262332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ickovics J, Niccolai L, Lewis J, Kershaw T, Ethier K. High postpartum rates of sexually transmitted infections among teens: Pregnancy as a window of opportunity for prevention. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2003;79:469–473. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.6.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakurt G, Cumbie T. The relationship between egalitarianism, dominance, and violence in intimate relationships. Journal of Family Violence. 2012;27:115–122. doi: 10.1007/s10896-011-9408-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J, Johnson M. Differentiation among types of intimate partner violence: Research update and implications for interventions. Family Court Review. 2008;46:476–499. [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Laurent H, Capaldi D, Feingold A. Men’s aggression toward women: A 10-year panel study. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:1169–1187. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00558.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey K, McPherson M, Samuel P, Powell Sears K, Head D. The impact of different types of intimate partner violence on the mental and physical health of women in different ethnic groups. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2013;28:359–385. doi: 10.1177/0886260512454743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawoko S, Dalal K, Jiayou L, Jansson B. Social inequalities in intimate partner violence: A study of women in Kenya. Violence and Victims. 2007;22:773–784. doi: 10.1891/088667007782793101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson D, Brossart D. Interpersonal problems and personality features as mediators between attachment and intimate partner violence. Violence and Victims. 2013;28:414–428. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.vv-d-12-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Raja E, Lee A, Bhattacharya S, Bhattacharya S, Norman J, Reynolds R. Maternal obesity during pregnancy associates with premature mortality and major cardiovascular events in later life. Hypertension. 2015;66:938–944. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindhorst T, Oxford M. The long-term effects of intimate partner violence on adolescent mothers’ depressive symptoms. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;66:1322–1333. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky S, Holt VL, Easterling TR, Critchlow CW. Police-reported intimate partner violence during pregnancy: Who is at risk? Violence & Victims. 2005;20:69–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macke CA. Adult romantic attachment as a risk factor for intimate partner violence victimization. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences. 2011;72(6-A):2158. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall A, Jones D, Feinberg M. Enduring vulnerabilities, relationship attributions, and couple conflict: An integrative model of the occurrence and frequency of intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Psychology. 2011;25:709–718. doi: 10.1037/a0025279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milan S, Lewis J, Ethier K, Kershaw T, Ickovics J. Relationship violence among adolescent mothers: Frequency, dyadic nature, and implications for relationship dissolution and mental health. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2005;29:302–312. [Google Scholar]

- Miller E, Decker M, McCauley H, Tancredi D, Levenson R, Waldman J, … Silverman J. Pregnancy coercion, intimate partner violence and unintended pregnancy. Contraception. 2010;81:316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt T E-Risk Study Team. Teen-aged mothers in contemporary Britain. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43:727–742. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt T, Krueger R, Caspi A, Fagan J. Partner abuse and general crime: How are they the same? How are they different? Criminology. 2000;38:199–232. [Google Scholar]

- Nemeth JM, Bonomi AE, Lee MA, Ludwin JM. Sexual infidelity as trigger for intimate partner violence. Journal of Women’s Health. 2012;21:942–949. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.3328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norlander B, Eckhardt C. Anger, hostility, and male perpetrators of intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:119–152. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary K, Slep A. Prevention of partner violence by focusing on behaviors of both young males and females. Prevention Science. 2012;13:329–339. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orcutt H, Garcia M, Pickett S. Female-perpetrated intimate partner violence and romantic attachment style in a college sample. Violence & Victims. 2005;20:287–302. doi: 10.1891/vivi.20.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oringher J, Samuelson K. Intimate partner violence and the role of masculinity in male same-sex relationships. Traumatology. 2011;17:68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis A, Hébert M, Fernet M. Dyadic dynamics in young couples reporting dating violence: An actor-partner interdependence model. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2015:1–19. doi: 10.1177/0886260515585536. ePub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Próspero M. Effects of masculinity, sex, and control on different types of intimate partner violence perpetration. Journal of Family Violence. 2008;23:639–645. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Reidy D, Ball B, Houry D, Holland K, Valle L, Kearns M, … Rosenbluth B. In search of teen dating violence typologies. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2016;58:202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santana MC, Raj A, Decker MR, La Marche A, Silverman JG. Masculine gender roles associated with increased sexual risk and intimate partner violence perpetration among young adult men. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83:575–585. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9061-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar NN. The impact of intimate partner violence on women’s reproductive health and pregnancy outcome. Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2008;28:266–271. doi: 10.1080/01443610802042415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shneyderman Y, Kiely M. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: Victim or perpetrator? Does it make a difference? BJOG. 2013;120:1375–1385. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smithey M, Straus M. Primary prevention of intimate partner violence. In: Kury H, Obergfell-Fuchs J, editors. Crime prevention-new approaches. Mainz/Germany: Weisser Ring Gemeinnutzige Verslags-GmbH; 2004. pp. 239–276. [Google Scholar]

- Stith S, Smith D, Penn C, Ward D, Tritt D. Intimate partner physical abuse perpetration and victimization risk factors: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2004;10:65–98. [Google Scholar]

- Straus M. Gender symmetry and mutuality in perpetration of clinical-level partner violence: Empirical evidence and implications for prevention and treatment. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2011;16:279–288. [Google Scholar]

- Straus M, Hamby S, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman D. The revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan T, Meese K, Swan S, Mazure C, Snow D. Precursors and correlates of women’s violence: Child abuse traumatization, victimization of women, avoidance coping, and psychological symptoms. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2005;29:290–301. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton T, Simons L, Wickrama K, Futris T. The intergenerational transmission of violence: Examining the mediating roles of insecure attachment and destructive disagreement beliefs. Violence and Victims. 2014;29:670–687. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.vv-d-13-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitelman A, Ratcliffe S, Morales-Aleman M, Sullivan C. Sexual relationship power, intimate partner violence, and condom use among minority urban girls. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:1694–1712. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson E, Pleck J. The structure of male-role norms. American Behavioral Scientist. 1986;29:531–543. [Google Scholar]

- Traupmann J, Petersen R, Utne M, Hatfield E. Measuring equity in intimate relations. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1981;5:467–480. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine JM, Rodriguez MA, Lapeyrouse LM, Zhang M. Recent intimate partner violence as a prenatal predictor of maternal depression in the first year postpartum among Latinas. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2011;14:135–143. doi: 10.1007/s00737-010-0191-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger M. Patterns of misreporting intimate partner violence using matched pairs. Violence and Victims. 2015;30:179–193. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.vv-d-13-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White H, Widom C. Intimate partner violence among abused and neglected children in young adulthood: The mediating effects of early aggression, antisocial personality, hostility and alcohol problems. Aggressive Behavior. 2003;29:332–345. [Google Scholar]

- Widom C, Czaja S, Dutton M. Child abuse and neglect and intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration: A prospective investigation. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2014;38:650–663. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray A, Hoyt T, Gerstle M. Preliminary examination of a mutual intimate partner violence intervention among treatment-mandated couples. Journal of Family Psychology. 2013;27:664–670. doi: 10.1037/a0032912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]