Abstract

A role for infection and inflammation in atherogenesis is widely accepted. Arterial endothelium has been shown to express heat shock protein 60 (HSP60) and, since human (hHSP60) and bacterial (GroEL) HSP60s are highly conserved, the immune response to bacteria may result in cross-reactivity, leading to endothelial damage and thus contribute to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. In this study, GroEL-specific T-cell lines from peripheral blood and GroEL-, hHSP60-, and Porphyromonas gingivalis-specific T-cell lines from atherosclerotic plaques were established and characterized in terms of their cross-reactive proliferative responses, cytokine and chemokine profiles, and T-cell receptor (TCR) Vβ expression by flow cytometry. The cross-reactivity of several lines was demonstrated. The cytokine profiles of the artery T-cell lines specific for GroEL, hHSP60, and P. gingivalis demonstrated Th2 phenotype predominance in the CD4 subset and Tc0 phenotype predominance in the CD8 subset. A higher proportion of CD4 cells were positive for interferon-inducible protein 10 and RANTES, with low percentages of cells positive for monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 and macrophage inflammatory protein 1α, whereas a high percentage of CD8 cells expressed all four chemokines. Finally, there was overexpression of the TCR Vβ5.2 family in all lines. These cytokine, chemokine, and Vβ profiles are similar to those demonstrated previously for P. gingivalis-specific lines established from periodontal disease patients. These results support the hypothesis that in some patients cross-reactivity of the immune response to bacterial HSPs, including those of periodontal pathogens, with arterial endothelial cells expressing hHSP60 may explain the apparent association between atherosclerosis and periodontal infection.

Cardiovascular disease with an etiology of atherosclerosis is the main cause of death in Western societies. The importance of the role of infection and inflammation in the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis is now widely accepted. Controlled studies have shown that acute infections, especially bacterial respiratory infections, often precede the onset of symptoms of stroke or myocardial infarction by several weeks (18, 32, 34).

Chronic inflammatory periodontal disease is a significant oral health problem, with Porphyromonas gingivalis being one of the major causative organisms. Individuals with severe chronic periodontitis have been reported to have a significantly increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease, including atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, and stroke (5, 18, 34, 37). Although this association has been challenged by some (22), tooth loss levels, used as an indicator of cumulative periodontitis, have been significantly associated with peripheral arterial disease (23) and carotid artery plaque prevalence (6). Work on animal models further supports the association between periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease. Murine models of atherosclerosis have demonstrated that repeated intravenous or oral inoculation with P. gingivalis resulted in atherosclerotic lesions that were more advanced and developed more rapidly than those of control animals (27, 29).

Bacterial heat shock protein 60s (HSP60s), termed GroEL, are major antigenic determinants during infection (25) and, since human and bacterial HSPs have a >55% homology, it is possible that the immune response to bacterial challenge may result in cross-reactivity by targeting host cells expressing human HSP60 (hHSP60) (40). Arterial endothelium has been shown to express hHSP60 (1) caused possibly by stress factors such as hypertension or hypercholesterolemia, and the resulting endothelial damage may contribute to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis.

The outcome of an immune response is determined by the particular subsets of leukocytes that are recruited and subsequently activated within the lesion. A Th1 cytokine response has been shown to dominate the lesion of atherosclerosis with production of gamma interferon (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin-2 (IL-2) (8, 36). IFN-γ appears to be a central mediator of atherosclerosis. IFN-γ-deficient mice have been shown to develop lesions of reduced size, lipid accumulation, and cellularity but with increased fibrosis and collagen content, resulting in a more stable plaque (20). The Th1-inhibitory cytokine IL-10 is expressed in human atherosclerotic lesions in association with reduced inflammation (reviewed by Greaves and Channon [19]). The Th2 cytokine IL-4, on the other hand, has been shown to be uncommon in atherosclerotic lesions (8). Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) exhibits potent chemotactic activity for monocytes and has been demonstrated in human atherosclerotic plaques (33). IFN-inducible protein 10 (IP-10) specifically chemoattracts activated T cells. IFN-γ induces the expression of IP-10, which in turn, upregulates IFN-γ production (9), thereby contributing to the progression of the lesion. Neovascularization and healing are inhibited by IP-10, and this may increase the severity and instability of the plaque (30).

The aim of the present study was to establish and characterize T-cell lines from peripheral blood and atherosclerotic plaques obtained from subjects with atherosclerosis in terms of their cytokine and chemokine profiles and their T-cell receptor (TCR) Vβ expression and to investigate cross-reactivity with hHSP60, GroEL, and P. gingivalis outer membrane antigens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

Peripheral blood was obtained from 20 patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy at the Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital. Biopsy material from atherosclerotic plaques was also collected from 12 of these patients. Informed consent to use tissue that would otherwise have been discarded was obtained from each patient at the time of surgery. A written explanation of the purpose of the study was provided, and a signed consent form was obtained according to the Helsinki Declaration. Institutional ethics review committee approval to carry out the study was also obtained.

Periodontal status.

Periodontal disease status was classified as either healthy (no sites with a pocket depth of ≥3.5 mm), moderate (≥1 sites with a pocket depth of ≥3.5 mm and <4 sites with a pocket depth of ≥5 mm), or advanced (≥4 sites with a pocket depth of ≥5 mm). Five patients were edentate, and five patients did not consent to an oral examination.

Peripheral blood.

T-cell lines specific for bacterial GroEL were established from the peripheral blood of 12 patients and characterized in terms of their TCR Vβ repertoire and cytokine and chemokine profiles as described previously (10, 14, 16). Briefly, 50 ml of blood was taken from each patient, and the mononuclear cells isolated by Ficoll-Paque (Pharmacia LKB, Uppsala, Sweden) gradient centrifugation. A portion of the mononuclear cell suspension for use as antigen-presenting cells (APC) was placed into RPMI 1640 containing 10% dimethyl sulfoxide and glycerol and stored at −80°C. The other portion of the cell suspension was incubated at a concentration of 106 lymphocytes/ml with 5 ng of recombinant GroEL protein (purified from Escherichia coli with >90% purity; Stressgen Biotechnologies Corp., Victoria, British Columbia, Canada)/ml in RPMI 1640 containing 10% pooled human AB serum, 2 mM glutamine (ICN Biomedicals, Inc., Aurora, Ohio), 100 IU of penicillin/ml (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), 100 μg of streptomycin/ml (Sigma), and 1.25 μg of amphotericin B (Gibco, Paisley, Scotland, United Kingdom)/ml in 24-well plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air at 37°C.

After 14 days, the T cells were restimulated with GroEL (5 ng/ml), together with irradiated (30 Gy) autologous peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). rHIL-2 (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) was also added at this stage at a concentration of 10 U/ml so that the now specific T cells would proliferate. After a further 14 days, cells for the proliferation assay were ready for testing, whereas cells for flow cytometry were subjected to a further round of stimulation (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

T-cell lines established, assays performed, and periodontal status of patients in this study

| Patient no. | Periodontal status | Assay(s) performeda

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB line | PHA line | GroEL line | hHSP60 line | PGS line | ||

| 1 | Advanced | F, P | ||||

| 2 | Not known | F, P | ||||

| 3 | Advanced | F, P | ||||

| 4 | Not known | F | ||||

| 5 | Edentate | F, P | ||||

| 6 | Edentate | F, P | ||||

| 7 | Not known | F, P | ||||

| 8 | Not known | F, P | ||||

| 9 | Healthy | F, P | ||||

| 10 | Edentate | F, P | F, P | F, P | F, P | F, P |

| 11 | Edentate | F, P | F | F | F | F |

| 12 | Healthy | F, P | F, P | F, P | F, P | |

| 13 | Advanced | F, P | F, P | F, P | F, P | |

| 14 | Healthy | F, P | F, P | F, P | F, P | |

| 15 | Advanced | F, P | F, P | F, P | F, P | |

| 16 | Edentate | F, P | F, P | F, P | F, P | |

| 17 | Healthy | F, P | F, P | F, P | F, P | |

| 18 | Advanced | F, P | F, P | F, P | F, P | |

| 19 | Advanced | F, P | F, P | F, P | F, P | |

| 23 | Not known | F, P | ||||

The assays performed on the T-cell lines were flow cytometry (F) and proliferation assay (P). PB, GroEL-specific T-cell lines were established from peripheral blood. PHA expanded, GroEL-specific, hHSP60-specific, and P. gingivalis-specific (PGS) T-cell lines were established from atherosclerotic artery tissue.

Atherosclerotic lesions.

Cells were extracted from the atherosclerotic lesions of 10 patients by the method of De Boer et al. (4). After Ficoll-Paque density centrifugation, the mononuclear cells were incubated with 5 μg of the T-cell mitogen phytohemagglutinin (PHA)/ml, irradiated (30 Gy) autologous PBMC (5 × 105/ml), and IL-2 (10 U/ml). After 2 to 4 weeks, proliferation assays and flow cytometry were performed as described below. At 2 weeks, three cell lines were generated from a proportion of each PHA-expanded T-cell line by stimulation with GroEL (5 ng/ml), hHSP60 (5 ng/ml; does not contain GroEL and has low levels of endotoxin [<5 × 10−4 EU/well]; Stressgen), or P. gingivalis outer membrane antigens (0.5 μg/ml) (14, 16), along with irradiated autologous APC. The cells were restimulated with specific antigen and APC twice more at fortnightly intervals before proliferation assays and flow cytometry were performed as for the PHA lines (Table 1).

In order to test for effects due to the presence of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in the antigen preparations, P. gingivalis-specific, hHSP60-specific, and GroEL-specific lines established from one of the patients who demonstrated cross-reactivity were incubated with the appropriate antigen, along with polymyxin B at a concentration of 10 μg/ml (Sigma). Polymyxin B binds to endotoxin to inhibit its biological activity and is widely used to investigate the effect of any possible LPS contamination (35). The P. gingivalis outer membrane preparation has been shown to contain at least 32 antigens, 15 of which were attributed to LPS and 1 of which had a molecular mass of ∼65 kDa, indicating that the preparation contained both protein, including GroEL, and LPS antigens (13) and therefore could serve as a positive control for the activity of polymyxin B. Proliferative responses and cytokine profiles were determined as described below. The cross-reactive proliferative response of the hHSP60-specific line to P. gingivalis outer membrane antigens after the addition of polymyxin B was also confirmed. In addition, anti-HSP60 (LK1 clone; Stressgen) and anti-GroEL (Stressgen) antibodies were added to T cells in the hHSP60- and GroEL-specific lines, respectively, to confirm specificity of these lines. Anti-GroEL antibody was also added to the P. gingivalis-specific line to determine the effect of any P. gingivalis GroEL present in the outer membrane preparation.

Lymphoproliferation assay.

Lymphoproliferation assays were performed to investigate cross-reactivity of the specific T-cell lines with the remaining two antigens not used to establish the lines. Therefore, each cell line was stimulated with each of the three antigens: GroEL, hHSP60, and P. gingivalis outer membrane antigens. T cells from each line were cultured at a concentration of 105/well in flat-bottom 96-well tissue culture plates (Nunc), along with irradiated (30 Gy) autologous APC at a concentration of 104/well. The cells were stimulated with hHSP60 or GroEL at concentrations of 100.0, 10.0, 1.0, 0.1, 0.01, and 0 ng/well or P. gingivalis outer membrane antigens at concentrations of 10.0, 1.0, 0.1, 0.01, and 0 μg/well for 3 days. Quadruplicate wells were prepared for each antigen concentration. Cultures were pulsed with 0.5 μCi of [3H]thymidine 24 h prior to harvesting onto glass fiber disks. [3H]thymidine incorporation was measured by using a LS 6000SC Beckman scintillation counter.

Flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry was used to examine the TCR Vβ expression and the cytokine and chemokine profiles of the T cells in each line. The CD4 and CD8 T cells in the cultures were stained for intracytoplasmic IL-4, IFN-γ, IL-10, IP-10, MCP-1, macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α), and RANTES as described by Gemmell et al. (10, 16). Briefly, the T cells were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated mouse anti-human CD4 or CD8 (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.), followed by fixation of cells with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilization with proteinase K, and incubation with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated rat anti-human IL-4, IFN-γ, IL-10, IP-10, MCP-1, MIP-1α, or RANTES (Pharmingen). Surface membrane staining of the Vβ regions 3.1, 5.1, 5.2-3, 5.3, 6.7, 8.1, 8.2, 11.1, 12.1, 13.1, 13.3, 14.1, 16.1, 20.1, 21.3, and 22.1 was achieved by staining with PE-conjugated mouse anti-human CD4 or CD8 (Pharmingen), together with FITC-conjugated mouse anti-Vβ regions 3.1, 5.1, 5.2-3, 5.3, 6.7, 8.1, 8.2, 12.1, 13.1, and 13.3 (T-Cell Diagnostics, Cambridge, Mass.) or FITC-conjugated mouse anti-Vβ regions 11.1, 14.1, 16.1, 20.1, 21.3, or 22.1 (Immunotech, Marseille, France).

FITC- and PE-conjugated specific mouse or rat immunoglobulin isotypes (Dako) were used as negative controls. Ten thousand stained cells from each sample were analyzed by using dual-color flow cytometry on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.), and the percent CD4 and CD8 cells in the lines positive for each antigen were determined.

Statistics.

Multivariate analysis of variance with the general linear model was used to test for differences within and between the percentages of IL-4+, IFN-γ+, and IL-10+ CD4 and CD8 cells; MCP-1+, MIP-1α+, RANTES+, and IP-10+ CD4 and CD8 cells; and Vβ+ CD4 and CD8 cells. Pairs of groups were then tested for significance by using the Student t test. The Minitab statistical package (Minitab, Inc., State College, Pa.) was used to perform the analyses.

RESULTS

Periodontal status.

Of the 15 patients who consented to an oral examination, 4 were characterized as healthy, 6 had advanced periodontal disease, and 5 were edentate (Table 1).

Lymphoproliferation assay.

Variations occurred in the proliferative responses of the individual GroEL-specific T-cell lines established from the peripheral blood of atherosclerosis patients. Although some GroEL-specific T-cell lines did not respond to hHSP60 or P. gingivalis, 3 of the 11 lines did proliferate in response to at least one of these two antigens. One line responded to hHSP60 (P < 0.013) and also to P. gingivalis (P < 0.001), and two other GroEL-specific T-cell lines responded to P. gingivalis (P < 0.017) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Cross-reactive proliferative responses of T-cell lines established from peripheral blood

| Patient no./line specificity | T-cell response (dpm)a

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GroEL concn/well

|

hHSP60 concn/well

|

P. gingivalis concn/well

|

|||||||||||||

| 0 ng | 0.01 ng | 0.1 ng | 1 ng | 10 ng | 100 ng | 0.01 ng | 0.1 ng | 1 ng | 10 ng | 100 ng | 0.01 μg | 0.1 μg | 1 μg | 10 μg | |

| 1/GroEL+ | 40,324 | 39,716 | 41,359 | 42,777 | 40,007 | 34,467 | 41,965 | 43,773 | 41,926 | 37,418 | 34,081 | 14,713 | 14,505 | 14,274 | 12,305 |

| 2/GroEL+ | 11,893 | 12,182 | 12,716 | 12,449 | 11,910 | 12,055 | 11,386 | 12,940 | 13,022 | 10,291 | 10,009 | 46,080 | 46,618 | 46,103 | 23,690 |

| 3/GroEL+ | 148,480 | 141,897 | 141,042 | 147,095 | 140,886 | 135,241 | 133,835 | 140,267 | 135,107 | 125,188 | 129,257 | 156,599 | 157,559 | 148,499 | 94,691 |

| 5/GroEL+ | 98,306 | 98,385 | 98,449 | 100,507 | 98,635 | 88,132 | 95,704 | 97,332 | 100,854 | 94,700 | 90,713 | 100,595 | 105,487 | 101,353 | 95,549 |

| 6/GroEL+ | 151,387 | 152,748 | 147,196 | 136,660 | 135,380 | 132,373 | 163,799e | 169,862c | 172,002d | 150,975 | 152,560 | 137,903 | 146,479 | 135,746 | 170,191b |

| 7/GroEL+ | 217,363 | 217,765 | 212,453 | 206,950 | 204,095 | 198,364 | 208,914 | 210,655 | 207,186 | 207,228 | 201,256 | 213,197 | 210,723 | 207,554 | 203,342 |

| 8/GroEL+ | 58,545 | 55,171 | 56,002 | 64,477 | 68,667 | 61,699 | 46,054 | 56,656 | 62,136 | 58,497 | 54,312 | 62,592 | 60,841 | 61,699 | 16,393 |

| 9/GroEL+ | 127,064 | 127,193 | 127,048 | 130,448 | 126,706 | 127,256 | 125,812 | 127,704 | 137,604 | 130,280 | 124,785 | 123,248 | 129,855 | 151,766b | 187,047 |

| 10/GroEL+ | 166,540 | 164,737 | 166,760 | 161,639 | 169,405 | 172,041 | 164,707 | 164,367 | 162,489 | 165,983 | 147,065 | 170,285 | 170,100 | 167,092 | 156,634 |

| 11/GroEL+ | 62,050 | 57,382 | 62,538 | 61,372 | 61,943 | 65,187 | 58,910 | 59,442 | 58,309 | 58,465 | 60,264 | 69,737 | 62,672 | 63,432 | 58,088 |

| 23/GroEL+ | 198,077 | 208,401 | 218,212 | 232,599 | 229,211 | 229,104 | 195,451 | 204,140 | 200,014 | 194,573 | 211,756 | 226,137c | 234,564a | 229,391f | 154,044 |

Values in boldface indicate mean cross-reactive proliferative responses of T cells that were significantly different from control wells (zero concentration/well). Superscript letters: a, P < 0.001; b, P < 0.002; c, P < 0.003; d, P < 0.010; e, P < 0.013; f, P < 0.017.

Proliferation studies were carried out on artery lines from 9 of the 10 subjects. Several specific T-cell lines derived from individual patients exhibited cross-reactivity. Three cell lines established from atherosclerotic plaque tissue specific for hHSP60 showed responses to GroEL (P < 0.043). One GroEL-specific artery T-cell line demonstrated a significant response to hHSP60 (P < 0.049). In addition, the P. gingivalis specific line from this patient proliferated in response to GroEL (P < 0.004). Five GroEL-specific lines responded to P. gingivalis (P < 0.031), and three hHSP60-specific lines proliferated in response to P. gingivalis (P < 0.015) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Cross-reactive proliferative responses of T-cell lines established from artery tissue

| Patient no./line specificity | T-cell response (dpm)a

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 ng | GroEL concn/well

|

hHSP60 concn/well

|

P. gingivalis concn/well

|

||||||||||||

| 0.01 ng | 0.1 ng | 1 ng | 10 ng | 100 ng | 0.01 ng | 0.1 ng | 1 ng | 10 ng | 100 ng | 0.01 μg | 0.1 μg | 1 μg | 10 μg | ||

| 10/GroEL+ | 56,255 | 56,111 | 55,526 | 56,518 | 55,493 | 55,213 | 56,146 | 58,441 | 51,535 | 49,538 | 52,258 | 61,554 | 57,093 | 52,104 | 36,739 |

| 12/GroEL+ | 112,213 | 102,945 | 100,773 | 107,737 | 113,075 | 109,134 | 107,391 | 97,235 | 106,225 | 98,936 | 100,773 | 114,251 | 117,447 | 95,531 | 58,971 |

| 13/GroEL+ | 123,259 | 117,283 | 127,162 | 133,522 | 127,908 | 117,147 | 132,241 | 136,616 | 132,877 | 115,765 | 127,796 | 151,378k | 145,489 | 119,488 | 73,344 |

| 14/GroEL+ | 114,154 | 102,903 | 106,110 | 115,112 | 120,663 | 112,573 | 102,721 | 96,335 | 105,356 | 100,123 | 98,022 | 114,443 | 104,797 | 84,404 | 55,197 |

| 15/GroEL+ | 100,525 | 104,741 | 109,943 | 130,557 | 132,087 | 126,983 | 111,367 | 117,927n | 89,522 | 86,068 | 91,031 | 108,222 | 110,737 | 92,967 | 66,867 |

| 16/GroEL+ | 59,723 | 57,067 | 61,382 | 70,472 | 75,273 | 76,522 | 56,958 | 63,518 | 64,019 | 54,926 | 57,058 | 89,725a | 81,843b | 66,224i | 48,819 |

| 17/GroEL+ | 30,191 | 30,674 | 29,768 | 32,725 | 32,141 | 30,316 | 25,271 | 26,863 | 27,917 | 25,377 | 25,271 | 33,658a | 32,564j | 27,531 | 13,150 |

| 18/GroEL+ | 99,787 | 99,236 | 97,817 | 106,899 | 101,896 | 102,921 | 93,846 | 92,831 | 94,783 | 91,383 | 97,086 | 110,437a | 111,673b | 95,291 | 52,427 |

| 19/GroEL+ | 21,073 | 20,783 | 22,669 | 23,284 | 22,121 | 25,200 | 20,453 | 19,851 | 21,137 | 20,267 | 19,989 | 24,217b | 24,196d | 18,511 | 5,860 |

| 10/HSP60+ | 52,144 | 52,101 | 51,591 | 61,201 | 60,647 | 55,608 | 51,161 | 52,519 | 54,547 | 48,810 | 51,023 | 60,367 | 61,356 | 57,375 | 39,363 |

| 12/HSP60+ | 154,419 | 148,751 | 145,405 | 165,495h | 175,933a | 168,702 | 150,391 | 141,798 | 149,136 | 143,243 | 143,239 | 152,084 | 157,686 | 143,430 | 95,820 |

| 13/HSP60+ | 161,256 | 151,374 | 145,385 | 163,468 | 155,186 | 158,158 | 137,853 | 143,150 | 149,680 | 140,790 | 140,828 | 167,342 | 157,740 | 133,049 | 86,585 |

| 14/HSP60+ | 126,689 | 113,996 | 116,111 | 130,229 | 121,527 | 130,161 | 110,389 | 112,592 | 112,744 | 103,375 | 109,567 | 139,902 | 121,982 | 106,837 | 63,115 |

| 15/HSP60+ | 120,140 | 109,825 | 115,135 | 114,132 | 114,259 | 111,698 | 100,874 | 106,585 | 88,119 | 95,324 | 97,568 | 101,199 | 95,727 | 87,565 | 66,604 |

| 16/HSP60+ | 63,589 | 61,425 | 65,179 | 69,555 | 70,914 | 69,689m | 60,958 | 68,925 | 64,286 | 60,637 | 59,233 | 88,851a | 79,093a | 69,353l | 47,340 |

| 17/HSP60+ | 27,981 | 30,684k | 29,315 | 32,103f | 32,246e | 30,144 | 25,623 | 27,233 | 26,754 | 27,879 | 25,256 | 29,492 | 33,964a | 27,669 | 14,415 |

| 18/HSP60+ | 114,787 | 103,057 | 104,165 | 102,212 | 115,032 | 112,303 | 93,771 | 100,485 | 110,297 | 100,735 | 105,113 | 119,950 | 117,700 | 95,056 | 51,398 |

| 19/HSP60+ | 20,911 | 20,442 | 21,383 | 22,415 | 22,556 | 22,993 | 17,895 | 19,799 | 20,251 | 19,345 | 18,940 | 23,259 | 24,869g | 19,417 | 5,689 |

| 10/PgOM+ | 69,378 | 63,054 | 58,996 | 72,562 | 68,740 | 60,627 | 55,622 | 56,546 | 62,051 | 59,298 | 60,543 | 61,107 | 60,732 | 56,489 | 37,161 |

| 12/PgOM+ | 129,973 | 123,844 | 121,117 | 135,284 | 130,631 | 135,191 | 121,449 | 118,529 | 128,540 | 124,016 | 124,842 | 152,974 | 124,528 | 117,804 | 78,156 |

| 13/PgOM+ | 171,366 | 167,259 | 165,235 | 166,894 | 169,776 | 184,356 | 153,737 | 162,395 | 164,832 | 151,138 | 163,584 | 194,701 | 162,895 | 148,355 | 99,642 |

| 14/PgOM+ | 132,282 | 128,972 | 128,909 | 124,284 | 127,834 | 131,926 | NA | NA | 126,110 | 115,828 | 119,636 | 135,231 | NA | NA | NA |

| 15/PgOM+ | 74,150 | 72,402 | 76,523 | 77,069 | 90,750c | 96,987b | 74,909 | 76,041 | 56,614 | 63,470 | 64,034 | 72,281 | 72,054 | 76,507 | 51,319 |

| 16/PgOM+ | 84,178 | 83,806 | 85,243 | 85,775 | 82,601 | 80,609 | 68,338 | 80,544 | 80,565 | 75,517 | 77,330 | 90,146 | 81,055 | 73,139 | 48,867 |

| 17/PgOM+ | 26,177 | 24,298 | 25,075 | 27,539 | 25,796 | 24,923 | 21,185 | 23,420 | 24,279 | 21,412 | 22,249 | 27,102 | 26,967 | 21,987 | 10,561 |

| 18/PgOM+ | 117,828 | 101,951 | 108,620 | 103,925 | 118,959 | 110,349 | 96,179 | 101,419 | 105,731 | 97,194 | 99,004 | 112,778 | 110,039 | 86,605 | 47,112 |

| 19/PgOM+ | 43,985 | 41,374 | 42,938 | 46,448 | 45,452 | 42,139 | 38,173 | 41,427 | 42,463 | 39,844 | 37,532 | 44,063 | 46,738 | 35,910 | 12,854 |

Values in boldface indicate cross-reactive proliferative responses of T cells that were significantly different from control wells (zero concentration/well). Superscript letters: a, P < 0.001; b, P < 0.002; c, P < 0.004; d, P < 0.005; e, P < 0.007; f, P < 0.01; g, P < 0.015; h, P < 0.021; i, P < 0.022; j, P < 0.024; k, P < 0.031; l, P < 0.036; m, P < 0.043; n, P < 0.049. NA, data not available.

Cytokines.

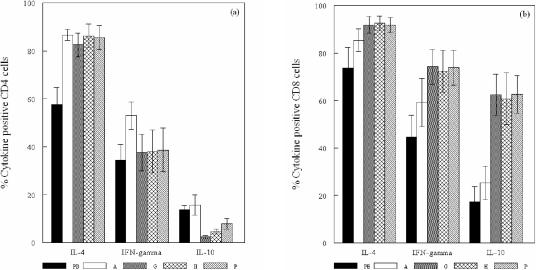

The mean percentage of IL-4+ CD4 and CD8 cells in the GroEL-specific T-cell lines established from the peripheral blood of atherosclerosis patients was higher than the percentages of IFN-γ+ and IL-10+ T cells (P < 0.032), with the mean percentage of both IL-4+ and IFN-γ+ CD4 and CD8 T cells being higher than that of IL-10+ cells (P < 0.025) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Mean ± the standard error of the mean percentage of CD4 cells (a) and CD8 cells (b) positive for IL-4, IFN-γ, and IL-10 in GroEL-specific T-cell lines derived from peripheral blood (PB), PHA-expanded (A), GroEL-specific (G), hHSP60-specific (H), and P. gingivalis outer membrane antigen (P)-specific T-cell lines derived from atherosclerotic plaques.

The PHA-expanded T-cell line and the three specific T-cell lines established from each of the atherosclerotic plaques demonstrated cytokine profiles similar to those of the peripheral blood lines. Again, the percentage of IL-4+ CD4 and CD8 cells was higher than IFN-γ+ and IL-10+ T cells (P < 0.046), and the percentage of IL-4+ and IFN-γ+ CD4 cells was greater than that of IL-10+ CD4 cells (P < 0.005). However, in contrast to the peripheral blood and the PHA-expanded artery T-cell lines, the artery lines specific for GroEL, hHSP60, and P. gingivalis demonstrated marked differences between the CD4 and CD8 populations. Although the percentages of IL-4+ CD4 and CD8 cells were similar, the CD8 subset demonstrated a Tc0 profile with an increase in the percentages of IFN-γ+ and IL-10+ CD8 cells (P < 0.014) compared to the CD4 population, which demonstrated a Th2 profile. The results clearly demonstrated a subset of T cells positive for both IL-4 and IFN-γ, and the mean percentages of CD4 and CD8 cells that expressed IL-4 only, IFN-γ only, or both IL-4 and IFN-γ are shown in (Table 4). In comparison to the peripheral blood and PHA-expanded artery T-cell lines, the percentage of IL-10+ CD4 cells was reduced in the GroEL- and hHSP60-specific T-cell lines (P < 0.021) but not in the P. gingivalis-specific artery T-cell line, whereas the percent IL-10+ CD8 cells was increased in the three specific lines (P < 0.015) (Fig. 1).

TABLE 4.

Th1, Th2, Th0, Tc1, Tc2, and Tc0 profiles in the T-cell lines

| T-cell line source | No. of samples | Mean % ± SEM

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 cells

|

CD8 cells

|

||||||

| IL-4− IFN-γ+a Th1 | IL-4+ IFN-γ−c Th2 | IL-4+ IFN-γ+b Th0 | IL-4− IFN-γ+a Tc1 | IL-4+ IFN-γ−c Tc2 | IL-4+ IFN-γ+b Tc0 | ||

| Periperal blood | 12 | 19.4 ± 2.8 | 42.8 ± 5.1 | 14.8 ± 6.7 | 14.8 ± 4.4 | 44.5 ± 9.4 | 29.3 ± 10.1 |

| PHA-expanded artery | 10 | 13.4 ± 2.2 | 47.1 ± 5.7 | 40.0 ± 6.7 | 13.8 ± 4.5 | 40.0 ± 9.8 | 45.4 ± 12.8 |

| GroEL+ artery | 10 | 11.6 ± 2.8 | 56.5 ± 6.4 | 26.0 ± 9.1 | 8.2 ± 3.5 | 25.8 ± 7.3 | 66.1 ± 10.2 |

| hHSP60+ artery | 10 | 8.1 ± 3.2 | 56.3 ± 7.4 | 29.9 ± 10.0 | 7.1 ± 2.8 | 27.3 ± 8.6 | 65.3 ± 11.6 |

| PgOM+ artery | 10 | 9.3 ± 2.8 | 56.2 ± 8.1 | 29.3 ± 9.6 | 8.3 ± 3.2 | 26.2 ± 7.3 | 65.6 ± 10.0 |

That is, % IFN-γ+ − (% IL-4 + IFN-γ+).

That is, (% IL-4+ + % IFN-γ+) − 100%.

That is, % IL-4+ − (% IL-4 + IFN-γ+).

CD4/CD8 ratio.

The mean CD4/CD8 ratio for the peripheral blood derived GroEL-specific T-cell lines was ca. 6/1, and this was significantly higher than that of the PHA-expanded and the GroEL-specific, hHSP60-specific, and P. gingivalis-specific lines established from atherosclerotic plaque tissue (ca. 0.6/1) (P < 0.001).

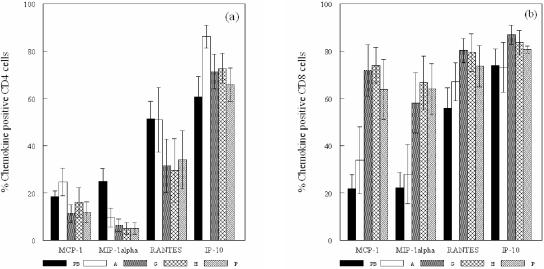

Chemokines.

In the peripheral blood T-cell lines, the percentages of cells positive for RANTES and IP-10 were significantly greater than for MCP-1 and MIP-1α (P < 0.009) (Fig. 2). The PHA artery lines showed higher percentages of RANTES+ and IP-10+ cells than MIP-1α+ cells (P < 0.027), whereas the mean percentage of IP-10+ cells was higher than for MCP-1 (P ≤ 0.05). A comparison of the peripheral blood and PHA lines showed that the mean percentage of IP-10+ CD4 cells only in the PHA lines was significantly higher (P < 0.037) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Mean ± the standard error of the mean percentage of CD4 cells (a) and CD8 cells (b) positive for MCP-1, MIP-1α, RANTES, and IP-10 in GroEL-specific T-cell lines derived from peripheral blood (PB), PHA-expanded (A), GroEL-specific (G), hHSP60-specific (H), and P. gingivalis outer membrane antigen (P)-specific T-cell lines derived from atherosclerotic plaques.

As with the cytokine profiles, there were large differences in the chemokines produced by the CD4 and CD8 cells in the GroEL-, hHSP60-, and P. gingivalis-specific artery T-cell lines. The percentage of CD4 cells positive for IP-10 was significantly greater than for MCP-1, MIP-1α, and RANTES (P ≤ 0.05), while there were significantly higher percentages of MCP-1+, MIP-1α+, and RANTES+ CD8 cells than CD4 cells (P < 0.027). The specific artery T-cell lines also demonstrated higher percentages of MCP-1+ and MIP-1α+ CD8 cells (P < 0.013) and reduced levels of MIP-1α+ CD4 cells compared to the peripheral blood lines (Fig. 2) (P < 0.032).

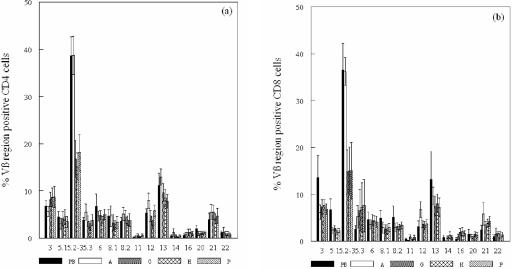

TCR Vβ expression.

The mean frequencies of CD4 and CD8 cells in the T-cell lines showed that all 15 TCR Vβ families examined were expressed. Approximately 38 and 36% of the CD4 and CD8 cells, respectively, in the GroEL-specific T-cell lines established from the peripheral blood and PHA-expanded artery lines expressed the 5.2-3 Vβ region, and this was significantly higher than that of the other 14 families, including the 5.3 region (P < 0.013 and P < 0.001, respectively), indicating that the 5.2 region was overexpressed. About 11 and 13% of the CD4 cells in the GroEL-specific peripheral blood lines and the PHA-expanded artery lines expressed the 13.1/13.3 regions, which was significantly greater than that of the other families except for 5.2-3 (P < 0.050 and P < 0.047, respectively) (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Mean ± the standard error of the mean percentage of CD4 cells (a) and CD8 cells (b) expressing 15 TCR Vβ families in GroEL-specific T-cell lines derived from peripheral blood (PB), PHA-expanded (A), GroEL-specific (G), hHSP60-specific (H), and P. gingivalis outer membrane antigen (P)-specific T-cell lines derived from atherosclerotic plaques (5.2 includes the Vβ regions 5.2 and 5.3).

The TCR Vβ profiles of the GroEL-, hHSP60-, and P. gingivalis-specific artery T-cell lines were all similar to the peripheral blood and PHA artery T-cell lines, with an over-representation of the 5.2-3 region. The Vβ 5.2-3 region was expressed by significantly more CD4+ cells than all other regions (P < 0.039) except for the 3.1 and 13.1/13.3 regions and the 8.1 in the GroEL-specific artery lines. The percentage of CD8+ cells of these lines expressing the 5.2-3 region was significantly higher than for only 6 of the other 14 families (P ≤ 0.05), although the mean percentage of 5.2-3 Vβ+ CD8 cells was reduced compared to the peripheral blood (P < 0.019) and PHA artery (P < 0.006) T-cell lines (Fig. 3).

LPS effects.

The addition of polymyxin B reduced the proliferative response by ca. 30% in the case of GroEL-specific and hHSP60-specific lines at both 3 and 6 days and at day 6 in the P. gingivalis-specific line. Cross-reactivity of the hHSP60-specific line with P. gingivalis was observed as determined previously (Table 3, patient 16). When the hHSP60-specific line was stimulated with P. gingivalis together with polymyxin B, the proliferative response was again reduced by ca. 30% compared to P. gingivalis alone; however, this response was still ca. 20% higher than when the T cells were incubated with hHSP60 and polymyxin B showing that cross-reactivity occurred even in the presence of polymyxin B.

Intracytoplasmic cytokine staining of these lines demonstrated that the cytokine profiles of these specific lines remained unchanged by the addition of polymyxin B to the cultures (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Effect of polymyxin B on cytokine profiles of T-cell lines

| T-cell line | % Positivea for:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 cells

|

CD8 cells

|

|||||

| IL-4 | IFN-γ | IL-10 | IL-4 | IFN-γ | IL-10 | |

| 16/PgOM+ | 84.79 | 74.68 | 3.82 | 89.36 | 86.46 | 62.14 |

| 16/PgOM+ (poly- myxin B added) | 91.21 | 66.57 | 9.92 | 95.48 | 83.63 | 50.53 |

| 16/hHSP60+ | 100.00 | 79.13 | 10.40 | 98.24 | 90.55 | 84.67 |

| 16/hHSP60+ (poly- myxin B added) | 98.25 | 60.22 | 4.43 | 98.20 | 95.18 | 79.26 |

| 16/GroEL+ | 68.27 | 11.07 | 4.67 | 81.58 | 78.52 | 80.01 |

| 16/GroEL+ (poly- myxin B added) | 68.46 | 9.88 | 8.28 | 93.38 | 72.05 | 82.92 |

Values are percent positive values for each cytokine (one sample per group) of T cells treated with or without polymyxin B (10 μg/ml).

The 3-day proliferative response of the GroEL-specific line was reduced by 18% after the addition of 10 μg of anti-GroEL antibody/ml and by 13% with the addition of 2.5 μg of anti-GroEL antibody/ml. Similarly, the hHSP60-specific line showed a reduction in 3-day proliferative responses of 20% with 10 μg of anti-hHSP60 antibody/ml and 8% with 2.5 μg of anti-hHSP60 antibody/ml. The addition of anti-GroEL antibody to the GroEL-specific line and anti-hHSP60 antibody to the hHSP60-specific line therefore reduced proliferation in a dose-dependent manner. Furthermore, the addition of P. gingivalis at 5 μg/ml to the P. gingivalis-specific line inhibited 3-day proliferative responses by 17%, whereas the addition of 10 μg of anti-GroEL antibody/ml negated this inhibition, demonstrating that in the P. gingivalis-specific lines the proliferative response to P. gingivalis GroEL was inhibitory.

Proliferation was therefore confirmed to be due to specific antigen even though reduction in proliferative responses after the addition of polymyxin B to the T-cell lines indicated that LPS effects may have been responsible for a proportion of the response.

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study have shown cross-reactivity in a number of GroEL- and hHSP60-specific T-cell lines to hHSP60 and GroEL, respectively. Since the hHSP60 antigen used contained no GroEL, these results support the existence of molecular mimicry between GroEL and hHSP60. Other lines that did not demonstrate cross-reactivity may contain T cells which recognize non-cross-reactive epitopes. Interestingly, a GroEL-specific line and a P. gingivalis-specific line established from the arterial tissue of one patient cross-reacted with hHSP60 and GroEL, respectively, suggesting that the HSP component of the P. gingivalis preparation was an important antigenic determinant, at least in this patient. This patient also had advanced periodontitis, and it is possible that the immune response to this infection may have influenced the specificity of the T cells recruited to the atherosclerosis lesion. Indeed, Yamazaki et al. (42) have shown that in periodontitis patients but not in control subjects clonal expansion of PBMC was preferentially induced by hHSP60 and P. gingivalis GroEL, and this occurred in an antigen-specific manner.

The present study also demonstrated that specific T-cell lines could be established in response to each of the three antigens from all subjects, regardless of their periodontal status. In contrast, Choi et al. (3) were able to establish P. gingivalis- and P. gingivalis GroEL-specific T-cell lines from the atherosclerotic lesions and the peripheral blood of patients with periodontitis but not from those without periodontitis. However, whereas these authors conducted dose-response assays of the P. gingivalis GroEL-specific lines, they were unable to demonstrate any significant responses, probably due to the magnitude of these proliferations, which were extremely low. T-cell lines maintained long term and subjected to repeated rounds of restimulation with specific antigen to ensure specificity respond differently to PBMC with regard to proliferation assays, and this has been shown previously (17). Although PBMC show a clear dose response, T-cell lines, as shown in the present study, demonstrated high proliferations even when unstimulated (i.e., zero concentration/well), probably due to the continual restimulation of these cells with specific antigen, in contrast to the PBMC that are starting from a resting or inactivated state. However, any response by the T-cell lines that is significantly higher than that of the unstimulated cells must represent a true proliferative response.

The cytokine profiles of the peripheral blood T-cell lines and the PHA-expanded artery lines showed a trend toward a Th2 profile particularly in the CD8 cells with a higher percentage positive for IL-4 than for IFN-γ and only a small percentage of cells positive for IL-10. This was also the case for the specific artery T-cell lines, although the percentage of IFN-γ+ and IL-10+ CD8 cells was greatly increased, shifting the balance of cytokines expressed to a Tc0 phenotype for the CD8 subset. This was shown by determining the percentage of cells that were possibly producing both IL-4 and IFN-γ. The proportion of these cells was increased in the artery T-cell lines compared to the peripheral blood lines, particularly in the CD8 subset. The presence of possible LPS contamination in the antigen preparations did not appear to have any effect on the cytokine profiles, as determined by the results obtained after addition of polymyxin B. T-cell clones derived from atherosclerotic plaques have previously been shown to be predominantly of a type 0 cytokine profile, although higher levels of IFN-γ compared to IL-4 were detected by using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (4). In another study, IL-4 was rarely observed in atherosclerotic plaques by using immunohistochemistry and PCR analysis (8). Interestingly, a cytokine profile similar to that demonstrated in the present study has also been reported to occur in T-cell lines established from gingival tissues of periodontitis patients (39) and in the peripheral blood of patients with periodontal disease (10).

The CD4/CD8 ratios of the artery T-cell lines were much reduced compared to those of the peripheral blood lines. This ratio has been shown to decrease with periodontal disease progression, indicating a role for both CD8 cells and CD4 cells in chronic periodontitis (15). Indeed, the present study has shown that both CD4 and CD8 cells in the lines established from atherosclerosis patients express cytokines in response to stimulation with GroEL, hHSP60, and P. gingivalis, suggesting an involvement of both subsets in atherosclerosis. Although histologically, fewer CD8 cells have been observed than CD4 cells in the lesion of atherosclerosis (28), a higher percentage of CD8 cells was found to be positive for the cytokines IFN-γ and IL-10 in the present study. It has been suggested that CD8 T cells expand both humoral and cellular responses in vivo by the production of chemokines at the peripheral site of infection (26). In this context, the results of the present study suggest that GroEL, hHSP60, and P. gingivalis may preferentially activate CD8 cells in the atherosclerotic lesion and that these cells have an important regulatory function even though fewer numbers are present in vivo than CD4 cells.

The chemokine profiles of the peripheral blood lines and the PHA-expanded artery lines demonstrated higher percentages of T cells positive for IP-10 and RANTES with low percentages of MCP-1- and MIP-1α-positive cells. Although CD4 cells in the specific artery T-cell lines had a similar profile, there was an increase in the percentages of positive CD8 cells, with no differences between the expression of the four chemokines. MCP-1 expression by monocytes has been shown to be regulated by IL-10 (38), and the clear correlation between MCP-1 and IL-10 levels demonstrated by the CD4 and CD8 cells of the specific artery T-cell lines suggests that this regulatory mechanism may also exist for T cells. Low levels of IL-10 and therefore of MCP-1, as seen in the CD4 subset, could indicate a reduction of cell-mediated responses. The predominance of IP-10+ T cells in both subsets observed in the present study has been demonstrated in situ, along with expression of the IP-10 receptor CXCR3 (31), suggesting that active recruitment of Th1 cells may occur (7). IP-10, MIP-1α, and RANTES attract Th1 CD4 cells and cytotoxic CD8 T cells (43), and therefore the expression of these chemokines especially by CD8 cells may regulate the cell-mediated component of the immune response. It has been postulated that the expression of IP-10 and RANTES, along with their respective receptors CXCR3 and CCR5, by the majority of the CD8 cells in oral lichen planus, may result in a self-recruiting mechanism involving activated effector cytotoxic T cells (24). The findings of the present study add to the evidence supporting the possibility of this mechanism also operating in atherosclerosis.

The present study has also shown that the Vβ5.2 family is the predominant TCR expressed by T cells in the GroEL-specific lines established from the peripheral blood of atherosclerosis patients, the PHA-expanded line, and the GroEL-specific, hHSP60-specific, and P. gingivalis-specific T-cell lines established from atherosclerotic plaque tissue, although in the specific artery lines this overexpression was less pronounced. The Vβ13 family appeared also to be more highly expressed. The Vβ5.2 region has previously been shown to be preferentially expressed by CD4 and CD8 cells in P. gingivalis-specific T-cell lines established from peripheral blood of both adult periodontitis and control subjects, and this overexpression of certain Vβ families was shown to be due to antigen-specific rather than superantigen activation (11).

The cytokine, chemokine, and Vβ profiles of the GroEL-, hHSP60-, and P. gingivalis-specific artery T-cell lines are remarkably alike. There is a high degree of homology between GroEL and hHSP60 (40), and the proliferation data after the addition of anti-GroEL antibody to the P. gingivalis-specific cell line indicates that HSPs could be an important antigen of the P. gingivalis outer membrane preparation. This idea is supported by the results of the proliferation assays which demonstrated that cross-reactivity did occur between these antigens at least in some patients. The results also showed that this cross-reactivity was most likely to hHSP60/GroEL rather than any possible LPS contamination in the antigen preparations. A number of studies have demonstrated the presence of multiple pathogens in atherosclerotic lesions. The organisms detected include Chlamydia pneumoniae, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, and, more recently, the oral bacteria P. gingivalis, Streptococcus sanguis, Tannerella forsythia, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, and Prevotella intermedia (2, 21, 41). In these studies almost all lesions examined were positive for at least one of the pathogens studied, and multiple species were detected in the majority of cases. Due to the homologous nature of HSPs across species, it is not surprising that we were able to establish T-cell lines specific for GroEL and P. gingivalis outer membrane antigens for each of the patients in the present study and that cross-reactivity was demonstrated in a number of these. In contrast, Choi et al. (3) were unable to show reactivity of P. gingivalis GroEL-specific T-cell lines with any other periodontopathic bacteria, including A. actinomycetemcomitans, Capnocytophaga sputigena, and Eikenella corrodens.

In conclusion, although these in vitro techniques give valuable insight into the role of HSP-specific T cells in the immune response associated with atherosclerosis, it is important that the effects of the complex interactions that occur in the host are not overlooked. The present study has demonstrated the presence of T cells specific for GroEL in the lesion of atherosclerosis and that cross-reactivity of these specific T cells with hHSP60 occurred. The artery T-cell lines specific for GroEL, hHSP60, and P. gingivalis demonstrated a Th2 phenotype predominance in the CD4 subset and a Tc0 phenotype predominance in the CD8 subset with a high proportion of CD8 cells expressing the chemokines IP-10, RANTES, MCP-1, and MIP-1α. Finally, there was an overexpression of the TCR Vβ5.2 family in all lines. The cytokine, chemokine, and Vβ results are similar to those demonstrated previously for P. gingivalis-specific lines from periodontal disease patients (10-12). Taken together, these results give strong support to the hypothesis (40) that cross-reactivity of the immune response to bacterial HSPs, including those of periodontal pathogens, with arterial endothelial cells expressing hHSP60 may be a mechanism involved in the disease process of atherosclerosis at least in some patients. The relative contribution, however, of this cross-reactivity to atherogenesis remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the Australian Dental Research Foundation.

We thank Julie Jenkins and Brian Henman for collecting the blood and artery tissues.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amberger, A., C. Maczek, G. Jurgens, D. Michaelis, G. Schett, K. Trieb, T. Eberl, S. Jindal, Q. Xu, and G. Wick. 1997. Co-expression of ICAM-1, VCAM-1, ELAM-1, and Hsp60 in human arterial and venous endothelial cells in response to cytokines and oxidized low-density lipoproteins. Cell Stress Chaperones 2:94-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiu, B. 1999. Multiple infections in carotid atherosclerotic plaques. Am. Heart J. 138:S534-S536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi, J.-I., S.-W. Chung, H.-S. Kang, B. Y. Rhim, S.-J. Kim, and S.-J. Kim. 2002. Establishment of Porphyromonas gingivalis heat-shock-protein-specific T-cell lines from atherosclerosis patients. J. Dent. Res. 81:344-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Boer, O. J., A. C. van der Wal, C. E. Verhagen, and A. E. Becker. 1999. Cytokine secretion profiles of cloned T cells from human aortic atherosclerotic plaques. J. Pathol. 188:174-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeStefano, F., R. F. Anda, S. Kahn, D. F. Williamson, and R. C. M. Russel. 1993. Dental disease and the risk of coronary heart disease and mortality. BMJ 306:688-691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desvarieux, M., R. T. Demmer, T. Rundek, B. Boden-Albala, D. R. Jacobs, P. N. Papapanou, and R. L. Sacco. 2003. Relationship between periodontal disease, tooth loss, and carotid artery plaque: the oral infections and vascular disease epidemiology study (INVEST). Stroke 34:2120-2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farber, J. M. 1997. Mig and IP-10: CXC chemokines that target lymphocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 61:246-257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frostegard, J., A. K. Ulfgren, P. Nyberg, U. Hedin, J. Swedenborg, U. Andersson, and G. K. Hansson. 1999. Cytokine expression in advanced human atherosclerotic plaques: dominance of pro-inflammatory (Th1) and macrophage-stimulating cytokines. Atherosclerosis 145:33-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gangur, V., F. E. Simons, and K. T. Hayglass. 1998. Human IP-10 selectively promotes dominance of polyclonally activated and environmental antigen-driven IFN-gamma over IL-4 responses. FASEB J. 12:705-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gemmell, E., C. L. Carter, D. A. Grieco, P. B. Sugerman, and G. J. Seymour. 2002. Porphyromonas gingivalis-specific T-cell lines produce Th1 and Th2 cytokines. J. Dent. Res. 81:303-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gemmell, E., D. A. Grieco, M. P. Cullinan, B. Westerman, and G. J. Seymour. 1998. Antigen-specific T-cell receptor Vb expression in Porphyromonas gingivalis-specific T-cell lines. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 13:355-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gemmell, E., D. A. Grieco, and G. J. Seymour. 2000. Chemokine expression in Porphyromonas gingivalis-specific T-cell lines. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 15:166-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gemmell, E., B. Polak, R. A. Reinhardt, J. Eccleston, and G. J. Seymour. 1995. Antibody responses of Porphyromonas gingivalis-infected gingivitis and periodontitis subjects. Oral Dis. 1:63-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gemmell, E., and G. J. Seymour. 1998. Cytokine profiles of cells extracted from humans with periodontal diseases. J. Dent. Res. 77:16-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gemmell, E., and G. J. Seymour. 1994. Modulation of immune responses to periodontal bacteria. Curr. Opin. Periodont. 94:28-38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gemmell, E., T. A. Winning, D. A. Grieco, P. Bird, and G. J. Seymour. 2000. The influence of genetic variation on the splenic T cell cytokine and specific serum antibody responses to Porphyromonas gingivalis in mice. J. Periodontol. 71:1130-1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gemmell, E., V. Woodford, and G. J. Seymour. 1996. Characterization of T lymphocyte clones derived from Porphyromonas gingivalis-infected subjects. J. Periodontal Res. 31:47-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grau, A., F. Buggle, C. Ziegler, W. Schwarz, J. Meuser, A.-J. Tasman, A. Buhler, C. Benesch, H. Becher, and W. Hacke. 1997. Association between acute cerebrovascular ischemia and chronic and recurrent infection. Stroke 28:1724-1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greaves, D. R., and K. M. Channon. 2002. Inflammation and immune responses in atherosclerosis. Trends Immunol. 23:535-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta, S., A. M. Pablo, X. Jiang, N. Wang, A. R. Tall, and C. Schindler. 1997. IFN-gamma potentiates atherosclerosis in ApoE knock-out mice. J. Clin. Investig. 99:2752-2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haraszthy, V. I., J. J. Zambon, M. Trevisan, M. Zeid, and R. J. Genco. 2000. Identification of periodontal pathogens in atheromatous plaques. J. Periodontol. 71:1554-1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hujoel, P., M. Drangsholt, C. Speikerman, and T. DeRouen. 2000. Periodontal disease and coronary heart disease risk. JAMA 284:1406-1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hung, H.-C., W. Willet, A. Merchant, B. A. Rosner, A. Ascherio, and K. J. Joshipura. 2003. Oral health and peripheral arterial disease. Circulation 107:1152-1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iijima, W., H. Ohtani, T. Nakayama, Y. Sugawara, E. Sato, H. Nagura, O. Yoshie, and T. Sasano. 2003. Infiltrating CD8+ T cells in oral lichen planus predominantly express CCR5 and CXCR3 and carry respective chemokine ligands RANTES/CCL5 and IP-10/CXCL10 in their cytolytic granules. Am. J. Pathol. 163:261-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kauffman, S. 1990. Heat shock proteins and the immune response. Immunol. Today 11:129-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim, J. J., L. K. Nottingham, J. I. Sin, A. Tsai, L. Morrison, J. Oh, K. Dang, Y. Hu, K. Kazahaya, M. Bennett, T. Dentchev, D. M. Wilson, A. A. Chalian, J. D. Boyer, M. G. Agadjanyan, and D. B. Weiner. 1998. CD8 positive T cells influence antigen-specific immune responses through the expression of chemokines. J. Clin. Investig. 102:1112-1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lalla, E., I. B. Lamster, M. A. Hofmann, L. Bucciarelli, A. P. Jerud, S. Tucker, Y. Lu, P. N. Papapanou, and A. M. Schmidt. 2003. Oral infection with a periodontal pathogen accelerates early atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-null mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 23:1405-1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee, W. H., Y. H. Ko, D. I. Kim, B. B. Lee, and J. E. Park. 2000. Prevalence of foam cells and helper-T cells in atherosclerotic plaques of Korean patients with carotid atheroma. Korean J. Intern. Med. 15:117-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li, L., E. Messas, E. L. Batista, R. A. Levine, and S. Amar. 2002. Porphyromonas gingivalis infection accelerates the progression of atherosclerosis in a heterozygous apolipoprotein E-deficient murine model. Circulation 105:861-867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luster, A. D., R. D. Cardiff, J. A. MacLean, K. Crowe, and R. D. Granstein. 1998. Delayed wound healing and disorganized neovascularization in transgenic mice expressing the IP-10 chemokine. Proc. Assoc. Am. Physicians 110:183-196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mach, F., A. Sauty, A. S. Iarossi, G. K. Sukhova, K. Neote, P. Libby, and A. D. Luster. 1999. Differential expression of three T lymphocyte-activating CXC chemokines by human atheroma-associated cells. J. Clin. Investig. 104:1041-1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mattila, K. 1989. Viral and bacterial infections in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J. Intern. Med. 225:293-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelken, N. A., S. R. Coughlin, D. Gordon, and J. N. Wilcox. 1991. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in human atheromatous plaques. J. Clin. Investig. 88:1121-1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Syrjanen, J., V. V. Valtonen, M. Iivanainen, M. Kaste, and J. K. Huttunen. 1988. Preceding infection as an important risk factor for ischemic brain infarction in young and middle aged patients. Br. Med. J. 296:1156-1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsan, M.-F., and B. Gao. 2004. Cytokine function of heat shock proteins. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 286:C739-C744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uyemura, K., L. Demer, S. C. Castle, D. Jullien, J. A. Berliner, M. K. Gately, R. R. Warrier, N. Pham, A. M. Fogelman, and R. L. Modlin. 1996. Cross-regulatory roles of interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-10 in atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Investig. 97:2130-2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Valtonen, V. V. 1999. Role of infections in atherosclerosis. Am. Heart J. 138:S431-S433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vestergaard, C., B. Gesser, N. Lohse, S. L. Jensen, S. Sindet Pedersen, K. Thestrup Pedersen, K. Matsushima, and C. G. Larsen. 1997. Monocyte chemotactic and activating factor (MCAF/MCP-1) has an autoinductive effect in monocytes, a process regulated by IL-10. J. Dermatol. Sci. 15:14-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wassenaar, A., C. Reinhardus, T. Thepen, L. Abraham Inpijn, and F. Kievits. 1995. Cloning, characterization, and antigen specificity of T-lymphocyte subsets extracted from gingival tissue of chronic adult periodontitis patients. Infect. Immun. 63:2147-2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wick, G. 2000. Atherosclerosis: an autoimmune disease due to an immune reaction against heat-shock protein 60. Herz 25:87-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamashita, K., K. Ouchi, M. Shirai, T. Gondo, T. Nakazawa, and H. Ito. 1998. Distribution of Chlamydia pneumoniae infection in the atherosclerotic carotid artery. Stroke 29:773-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamazaki, K., Y. Ohsawa, K. Tabeta, H. Ito, K. Ueki, T. Oda, H. Yoshie, and G. J. Seymour. 2002. Accumulation of human heat shock protein 60-reactive cells in the gingival tissues of periodontitis patients. Infect. Immun. 70:2492-2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshie, O., T. Imai, and H. Nomiyama. 2001. Chemokines in immunity. Adv. Immunol. 78:57-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]