Abstract

Purpose

Femorofemoral crossover bypass (FCB) is a good procedure for patients with unilateral iliac artery disease. There are many articles about the results of FCB, but most of them were limited to 5 years follow-up. The purpose of our study was to analysis the results of FCB with a 10-year follow-up period.

Materials and Methods

Between January 1995 and December 2010, 133 patients were operated in Samsung Medical Center (median follow-up: 58.8 months). We retrospectively analysed patient characteristics, the preoperative treatment, the operative procedure, and material used.

Results

The indications for FCB were claudication in 110 and critical limb ischemia in 23 patients. Three patients were died due to myocardiac infarction, intracranial hemorrhage, and acute respiratory failure within 30 days after surgery. The one-year primary and secondary patency rates were 89% and 97%, the 5-year primary and secondary patency rates were 70% and 85%, and the 10-year primary and secondary patency rates were 31% and 67%. The 5-year and 10-year limb salvage rates were 97% and 95%, respectively.

Conclusion

Our long term analysis suggests that FCB might be a valuable alternative treatment modality in patients with unilateral iliac artery disease.

Keywords: Femorofemoral, Bypass, Iliac artery, Vascular patency

INTRODUCTION

Since the introduction of femorofemoral crossover bypass (FCB) by Freeman and Leeds in 1952 [1], it has been used as an alternative to anatomic reconstruction for high risk patient with unilateral iliac occlusive disease. At present, most patients with symptomatic iliac stenosis or occlusion are treated primarily with angioplasty and stenting [2]. However, open surgical treatment is still recommended for a long iliac occlusion [3].

There have been many reports about the results of FCB. Most of the studies were limited to the 5 years results [4]. In order to examine the long-term usefulness of FCB and to determine which factors influence the outcome of the procedure, we retrospectively analyzed the FCB that was performed over a ten year period at our institution.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between January 1995 and December 2010, 133 patients were operated on for uni-lateral iliac occlusive disease at Samsung Medical Center (median follow-up: 58.8 months).

Our indication of FCB is an uniliac occlusive disease with good iliac artery as inflow and femoral artery as out flow. We retrospectively reviewed the medical record of the patients. The patients’ characteristics, including the demographic data, the cardiovascular risk factors, the indications for surgery, the preoperative treatment, the ankle–brachial pressure index, the operative procedure and material used and the medication after the operation were analyzed.

All patients were prescribed antiplatelet or anticoagulation and lipid-lowering medication during follow-up. Graft surveillance was performed using the ankle brachial index (ABI) after surgery and at 6 months, 12 months, and then annually. Computed tomography (CT) angiography or duplex scans were performed at 12 months and annually after bypass. Intervention was performed when occlusion and stenosis were observed on CT and duplex scans along with a decrease of >15% in the ABI score.

Chi-square tests or the Mann-Whitney U-test was used to compare the characteristics between the patent and occlusive groups. Wilcoson’s sign ranked test was used for pairwise comparison of the pre- and postoperative ankle–brachial pressure index. The cumulative patency rates were calculated with the Kaplan-Meier method. The factors influencing the long-term patency of the femorofemoral graft were tested with univariate and multivariate analyses. After univariate analysis with the log-rank test, the variables were applied into Cox’s proportional hazard model for multivariate analysis.

RESULTS

The patients’ characteristics, including the demographic data, the cardiovascular risk factors, the indications for surgery, the preoperative treatment, the ankle–brachial pressure index, the operative procedure are shown in Table 1, Table 2. Fifty patients were treated with donor iliac artery intervention preoperatively or intraoperatively.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Variable | Patient (n=133) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age (y) | 65±9.3 |

| Male | 126 (94.7) |

| Indication | |

| Claudication | 110 (82.7) |

| Critical limb ischemia | 23 (17.3) |

| Coexisting medical condition | |

| Smoking | 95 (71.4) |

| Hypertension | 79 (59.4) |

| Coronary artery disease | 37 (27.8) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 31 (23.3) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 24 (18.0) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 11 (8.3) |

| Chronic renal failure | 3 (2.3) |

| Malignancy | 8 (6.0) |

| Preoperative ABI | |

| Donor leg | 0.89±0.28 |

| Symptomatic leg | 0.48±0.26 |

| Postoperative ABI | |

| Donor leg | 0.82±0.31 |

| Symptomatic leg | 0.75±0.37 |

| Patent tibial artery (n) | |

| 1 | 24 (18.0) |

| 2 | 58 (43.6) |

| 3 | 51 (38.3) |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (%).

ABI, ankle brachial index.

Table 2.

Operative procedures and inflow procedures

| Operative procedure | Patient (n=133) |

|---|---|

| Graft material | |

| PTFE | 112 (84.2) |

| Dacron | 21 (15.8) |

| Flow direction | |

| Right to left | 68 (51.1) |

| Left to right | 65 (48.9) |

| Proximal anastomosis | |

| CFA | 121 (91.0) |

| SFA | 12 (9.0) |

| Distal anastomosis | |

| CFA | 101 (75.9) |

| SFA | 32 (24.1) |

| Femoral endarterectomy | |

| Yes | 26 (19.5) |

| No | 107 (80.5) |

| Inflow procedure | |

| Iliac endarectomy | 2 (1.5) |

| Iliac PTA | 50 (37.6) |

Values are presented as number (%).

PTFE, polytetrafluoroethylene; CFA, common femoral artery; SFA, supeficial femoral artery; PTA, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty.

The 30 days mortality was 2.26% (n=3). The causes of mortality were intracranial hemorrhage, acute respiratory failure and myocardial infarction. The mean follow-up period was 58.0 months (range, 1–156 months). During follow-up, 32 patients showed graft occlusion due to thrombosis. The mean interval time between femorofemoral bypass surgery to graft occlusion was 30.8 months (range, 0.2–107 months). Among 32 patients of graft occlusion, 25 patients (18.8%) underwent thrombectomy due to recurrent ischemic symptoms.

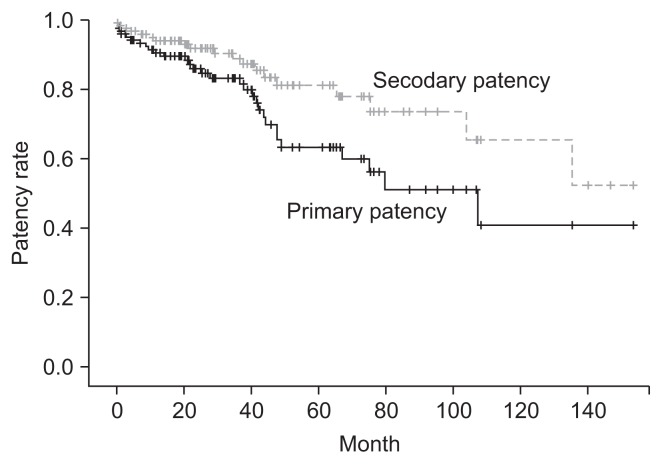

There were 2 infected grafts, and FCB graft removals were performed. After graft removals, ilio-femoral obturator bypass in one case and axillorfemoral bypass in other case were performed. Seventy-three patients were live and 16 were dead. Eleven patients were lost to follow-up. The overall primary cumulative patency rates at 1-, 3-, 5-, and 10-year were 89%±3%, 78%±4%, 70%±1%, and 31%±1%, respectively. The secondary cumulative patency rates at 1, 3, 5 and 10-year were 97%±2%, 90%±2%, 85%±4%, and 67%±7%, respectively (Fig. 1). The limb salvage rates at 5- and 10-year were 97% and 95%, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the primary and secondary cumulative patency of femorofemoral bypass shows that the one-year primary and secondary patency rates were 89%±3% and 97%±2%, the 5 year primary and secondary patency rates were 70%±1% and 85%±4% and the 10 year primary and secondary patency rates were 31%±1% and 67%±7%, respectively.

The influence of gender, age, cardiovascular factors, preoperative treatment and a simultaneous procedure on the clinical outcome and patency was examined. Univariate analysis revealed that smoking influenced the long term patency of the grafts, but on the multivariate analysis, none of the variables was associated with graft patency (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of the risk factors for graft occlusion (n=133)

| Variable | Uvivariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| 95% CI | P-value | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Age | 0.841–1.1256 | 0.62 | 0.904–1.017 | 0.908 |

| Gender | 0.034–13.017 | 1.00 | 0.072–10.318 | 0.918 |

| Smoking | 1.212–3.561 | 0.021 | 0.033–3.440 | 0.079 |

| Cerebral vascular disease | 1.131–2.128 | 0.012 | 0.022–1.495 | 0.112 |

| Hypertension | 0.898–2.954 | 0.098 | 0.509–3.332 | 0.581 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1.123–8.645 | 0.047 | 0.982–10.741 | 0.055 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.502–9.513 | 0.238 | 0.419–12.428 | 0.340 |

| Indication | 0.518–5.844 | 0.432 | 0.496–4.556 | 0.471 |

| Femoral endarectomy | 0.286–1.452 | 0.249 | 0.153–1.955 | 0.353 |

CI, confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

Different surgical approaches can be used to treat unilateral iliac artery occlusionn. Aortofemoral bypass is the procedure of choice in patients with severe iliac occlusive disease and who are at a low risk for a surgical procedure. More recently percutaneous transluminal angioplasty and stenting were introduced to treat stenosis and occlusion of TASC A or B in unilateral iliac occlusive disease. At present, the main anatomic indications to this surgical procedure are derived from the TASCII recommendations. The indications for surgery are long segment unilateral iliac disease corresponding to type C or D lesion [4]. FCB represents a valuable alternative option to anatomic bypass for unilateral iliac occlusive disease in patients with prohibitive surgical risks for aortic surgery or a poor general condition, coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or a local condition such as a hostile abdomen, sepsis or a porcelain aorta [5,6].

Our study showed a good patency rate like other FCB studies [3,4]. But Schneider et al. [7] reported that the results of FCB were clearly inferior to the results of aortofemoral bypass. Especially, younger patients profited from direct reconstruction. So it is necessary to conduct a randomized trial between direct reconstruction and extra-anatomical reconstruction.

In our study the perioperative mortality rate was 2.26%. In most of the previous studies, the perioperative mortality was reported as 0% to 5% [2,3,8]. More recently, several series have reported better long-term results with the operative mortality under 3% and the 5-year patency rate exceeding 90% [3,9]. In our study, the primary patency rate at 5 years was 70% and at 10 years it was 31%, but the secondary patency rate at 5 years was 85% and at 10 years it was 67%. Capoccia et al. [3] recently reported a 65%–83% primary patency rate at 5 years. Mingoli et al. [10] reported the at 10 years primary and secondary patency rates were 48.1% and 63.2%, respectively, like our study. Consequently, the reports that included the 5-year results were much more common for FCB, which allows a more confident assessment of long-term patency [11,12].

Our primary graft patency rate suddenly dropped at 36 months after bypass like other study. Graft occlusion occurring between 6 months and 3 years after surgery is usually due to anastomotic intimal hyperplasia [13]. Late graft thrombosis is often secondary to progression of distal atherosclerotic disease. Maybe more important factor effecting FCB graft patency rate is distal artery disease state after intimal hyperplasia.

In this study, no predictors and influencing factors for the patency rates were identified. Most of the studies dealing with FCB lacked a detailed description of several variables that might have substantially influenced the results. The various series have not supplied a detailed breakdown of the results on the basis of the operative indications, symptoms, failure of previous bypass grafts, the operative risk, the material used for reconstruction, the presence of an externally supported graft, preoperative evaluation of the donor iliac artery and the procedures adopted to improve the outflow [6,8,12]. The lack of well-defined categorizations of results according to these important variables creates a bias in the analysis of the long-term outcome. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, no randomized clinical studies have compared the results of FCB performed in patients at a low risk and who have with a good life expectancy.

Our study gives a detailed description of long term usefulness of FCB with taking into account not only the patency rates, but also the clinical efficacy. We conclude that FCB in patients with symptom caused by unilateral iliac artery disease is still a valuable alternative treatment modality.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Freeman NE, Leeds FH. Operations on large arteries; application of recent advances. Calif Med. 1952;77:229–233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jongkind V, Akkersdijk GJ, Yeung KK, Wisselink W. A systematic review of endovascular treatment of extensive aortoiliac occlusive disease. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:1376–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.04.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Capoccia L, Riambau V, da Rocha M. Is femorofemoral crossover bypass an option in claudication? Ann Vasc Surg. 2010;24:828–832. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2010.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ricco JB, Probst H French University Surgeons Association. Long-term results of a multicenter randomized study on direct versus crossover bypass for unilateral iliac artery occlusive disease. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.08.050. discussion 54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nolan KD, Benjamin ME, Murphy TJ, Pearce WH, McCarthy WJ, Yao JS, et al. Femorofemoral bypass for aortofemoral graft limb occlusion: a ten-year experience. J Vasc Surg. 1994;19:851–856. doi: 10.1016/S0741-5214(94)70010-9. discussion 857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim YW, Lee JH, Kim HG, Huh S. Factors affecting the long-term patency of crossover femorofemoral bypass graft. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;30:376–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneider JR, Besso SR, Walsh DB, Zwolak RM, Cronenwett JL. Femorofemoral versus aortobifemoral bypass: outcome and hemodynamic results. J Vasc Surg. 1994;19:43–55. doi: 10.1016/S0741-5214(94)70119-9. discussion 57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thuijls G, van Laake LW, Lemson MS, Kitslaar PJ. Usefulness and applicability of femorofemoral crossover bypass grafting. Ann Vasc Surg. 2008;22:663–667. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eiberg JP, Røder O, Stahl-Madsen M, Eldrup N, Qvarfordt P, Laursen A, et al. Fluoropolymer-coated dacron versus PTFE grafts for femorofemoral crossover bypass: randomised trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;32:431–438. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mingoli A, Sapienza P, Feldhaus RJ, Di Marzo L, Burchi C, Cavallaro A. Femorofemoral bypass grafts: factors influencing long-term patency rate and outcome. Surgery. 2001;129:451–458. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6060(01)70893-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pursell R, Sideso E, Magee TR, Galland RB. Critical appraisal of femorofemoral crossover grafts. Br J Surg. 2005;92:565–569. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mii S, Eguchi D, Takenaka T, Maehara S, Tomisaki S, Sakata H. Role of femorofemoral crossover bypass grafting for unilateral iliac atherosclerotic disease: a comparative evaluation with anatomic bypass. Surg Today. 2005;35:453–458. doi: 10.1007/s00595-004-2982-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park UJ, Kim DI. Thromoboagiitis Obliterans (TAO) Int J Stem Cells. 2010;3:1–7. doi: 10.15283/ijsc.2010.3.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]