Abstract

Purpose

With the long-term goal to optimize post-treatment cancer care in Asia, we conducted a qualitative study to gather in-depth descriptions from multiethnic Asian breast cancer survivors on their perceptions and experiences of cancer survivorship and their perceived barriers to post-treatment follow-up.

Methods

Twenty-four breast cancer survivors in Singapore participated in six structured focus group discussions. The focus group discussions were voice recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed by thematic analysis.

Results

Breast cancer survivors were unfamiliar with and disliked the term “survivorship,” because it implies that survivors had undergone hardship during their treatment. Cognitive impairment and peripheral neuropathy were physical symptoms that bothered survivors the most, and many indicated that they experienced emotional distress during survivorship, for which they turned to religion and peers as coping strategies. Survivors indicated lack of consultation time and fear of unplanned hospitalization as main barriers to optimal survivorship care. Furthermore, survivors indicated that they preferred receipt of survivorship care at the specialty cancer center.

Conclusion

Budding survivorship programs in Asia must take survivor perspectives into consideration to ensure that survivorship care is fully optimized within the community.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer survivorship care is still in its infancy in Asia. The majority of the institutions lack formal and standardized survivorship programs for cancer survivors. Yet, numerous challenges exist in the management of post-treatment complications within Asia. An observational study showed that cancer survivors in Asia suffer significant post-treatment–related symptoms, including anxiety, fatigue, and cognitive disturbances, and that these treatment-related complications are likely to have a major effect on health-related quality of life during cancer recovery.1 In addition, greater than 60% of the Southeast Asian oncology practitioners from numerous countries suggested that patient-specific barriers are the main barriers to follow-up care among the survivors they routinely treat.2 Because the success of survivorship care also depends greatly on the cooperation and participation of the survivors, it would be prudent to fully understand cancer survivorship from the end user perspective. Much of what is known about survivorship care and the issues faced by cancer survivors originates from studies that were conducted in the West, so ethnocultural differences may contribute to the delivery and experience of survivorship care among Asian cancer survivors.

With the long-term goal to optimize post-treatment care in breast cancer survivors in Asia, we conducted a qualitative study to gather in-depth descriptions from Asian breast cancer survivors on their perceptions and experiences of cancer survivorship and their perceived barriers to post-treatment follow-up.

METHODS

Design and Participants

As part of a study to evaluate the performance of group psychoeducation to improve survivorship in breast cancer survivors, a qualitative study was conducted at the National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS) that involved focus group discussions.3 NCCS is a leading regional center for cancer research and treatment in Southeast Asia, and it serves approximately 70% of all adult patients with cancer in Singapore.

The participants recruited for the focus group discussions fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: age older than 21 years, ability to read and understand English, diagnosis of early-stage breast cancer made by a medical oncologist, and completion of primary chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer. This study was approved by the SingHealth Centralized Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was obtained from all of the participants.

Procedures

Six English-speaking structured focus groups were conducted over 2 separate days. Four to six participants were included in each focus group, and grouping of the participants was based on the type of cancer treatment they had received. Each focus group discussion was designed to be 60 to 90 minutes long and was coordinated by trained facilitators. These facilitators were medical social workers, and each facilitator was assisted by one of the investigators as a note taker. The discussions used an open-ended approach that proceeded from a general question to more specific questions, which thus reduced the influence of probing by the facilitators. Two training sessions were held before the focus group discussions to ensure consistency in the facilitation of the groups.

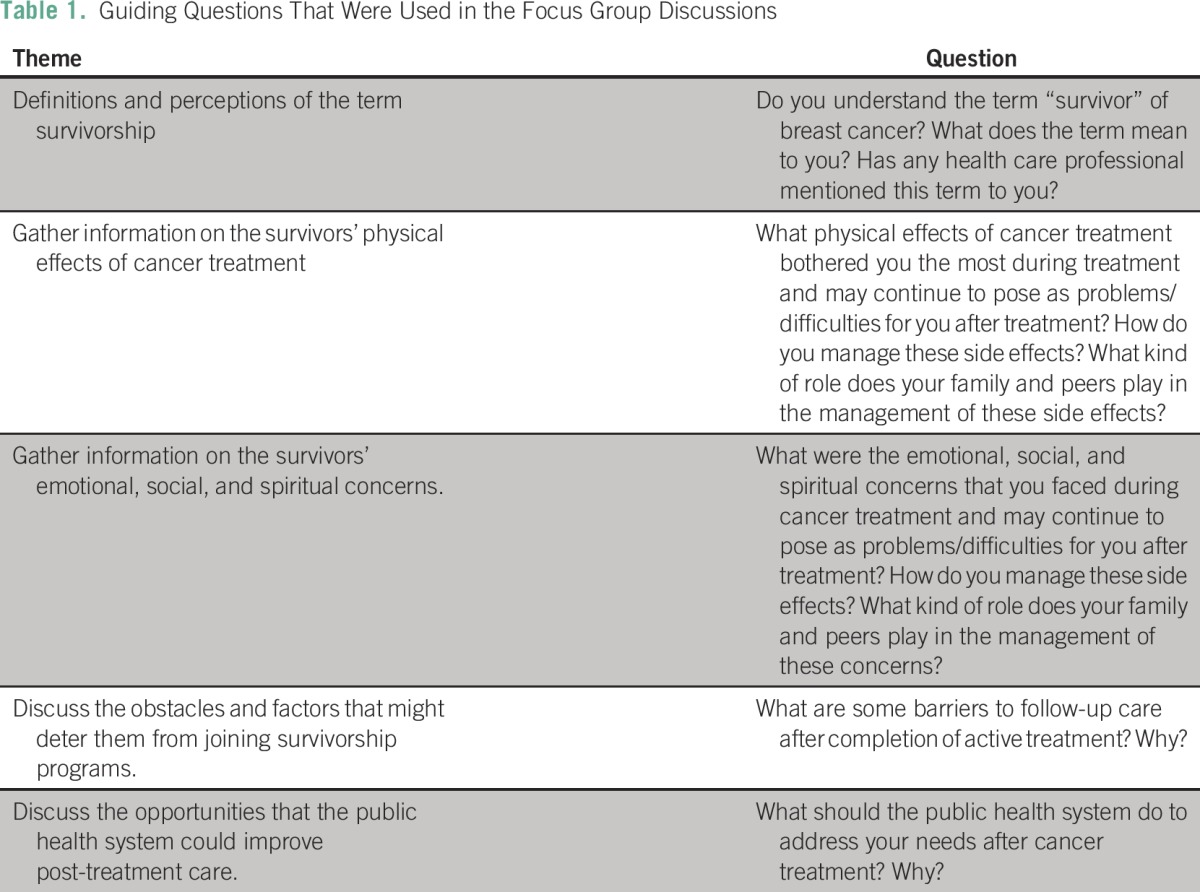

In each discussion, the facilitator would first understand the participant definitions and perception of the term survivorship and then gather information on the physical, emotional, social, and spiritual effects of cancer treatment on the survivor. Subsequently, the participants were asked to state the obstacles and factors that might deter them from joining survivorship programs (if offered; Table 1).

Table 1.

Guiding Questions That Were Used in the Focus Group Discussions

Data Analysis

The focus group discussions were voice-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed by thematic analysis.4 The open-ended discussion guide and data-driven analytical methods used in this study were adopted from certain elements of the grounded theory.5 Codes that described similar manifestations were grouped into themes. Two coders (L.Z.K. and A.C.) first familiarized themselves with the transcripts and generated initial codes independently. They then met to discuss and reach a consensus on the codes. Discrepancies were resolved with a consensus method.

RESULTS

Demographics

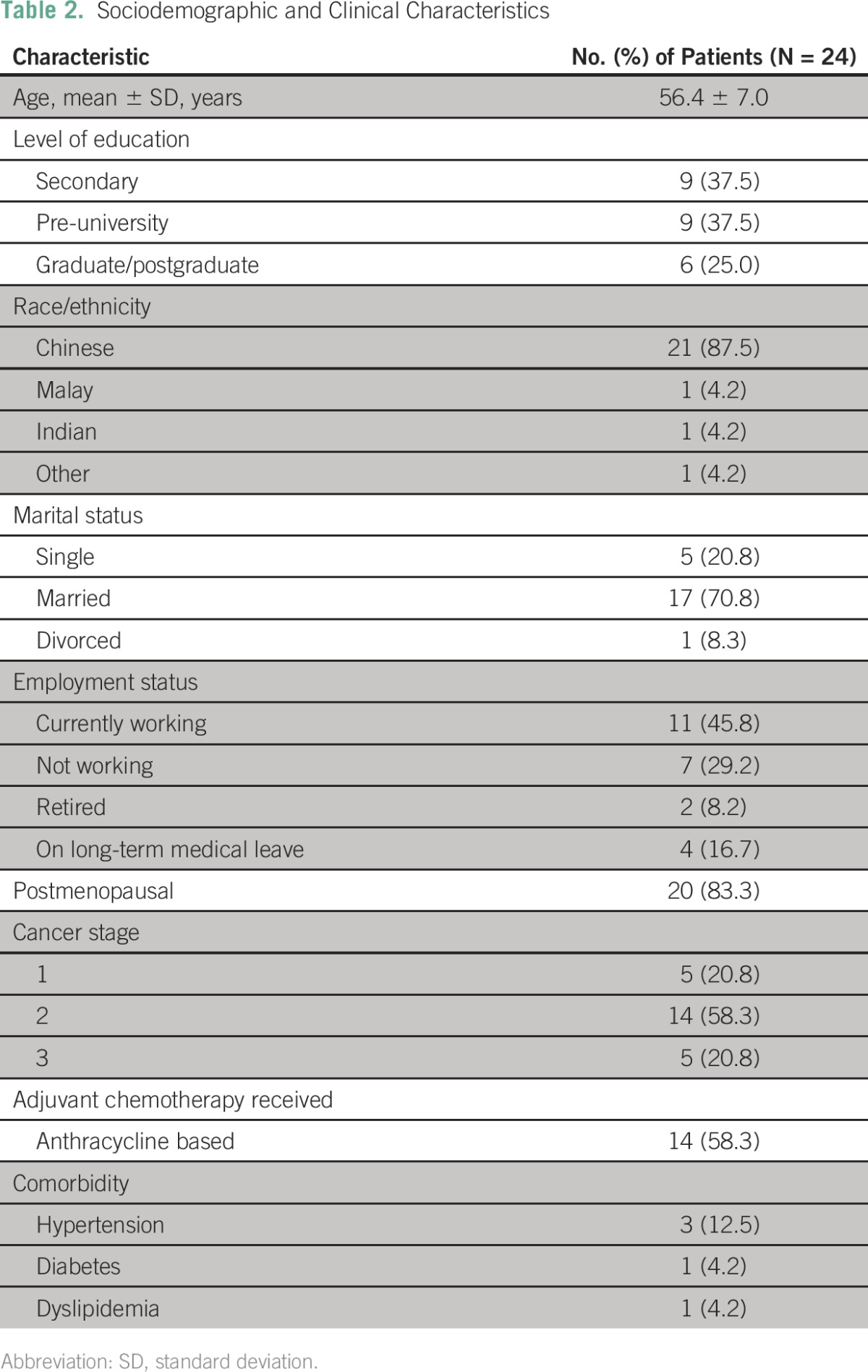

Twenty-four survivors participated in the six different focus groups. The mean (standard deviation) age was 56.4 years (± 7.0 years). Most of the survivors were Chinese (87.5%), were married (70.8%), and were diagnosed with stage II breast cancer (58.3%; Table 2).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

Open codes were created and categorized into five broad themes: understanding the terminology: who is a cancer survivor, physical issues, psychological issues, barriers to follow-up care, and how can the health care system address participants’ needs.

Understanding the Terminology: Who Is a Cancer Survivor?

A number of survivors understood the term survivorship as its literal meaning. However, two poles were observed through the discussions in terms of the definition of survivorship. Some survivors agreed that the connotation of survivorship is positive, but others viewed survivorship as a pessimistic description of their condition.

“Survivorship brings [me] a different kind of hope.”

“I am not sure do you need to wait for 5 years to be called a cancer survivor, or is it immediately now when you finished all your treatment […] Don’t really understand.”

Some survivors viewed survivorship as a negative reflection of their condition, and being tagged with the term survivor caused them emotional discomfort. The Chinese translation of the term survivorship implies that the survivors had undergone hardship during their treatment, and this is a term that was not favored by the survivors.

“Personally when I heard the word ‘survivor,’ it makes me go into sadness. I don’t like the term because it somehow [has] this connotation of […] barely getting by.”

Physical Symptoms

Cancer treatment brought about numerous physical adverse effects that affected the quality of life and personal relationships of survivors. Cognitive impairment, peripheral neuropathy, and fatigue were highlighted by most survivors. Hair loss, nausea, constipation, and mouth ulcers were other physical effects of cancer treatment that were experienced by numerous survivors during treatment.

Cognitive impairment.

A number of survivors indicated that their memory loss had affected their daily functioning, and they became dependent on others around them for daily living. This group of survivors was saddened by their memory loss, which indirectly affected their self-esteem.

“Last time I do work very independent[ly] […] I can guide people, but now I cannot. I still have to ask.”

These survivors overcame memory loss mainly through physical self-reminders by note-taking and by using certain tools to aid in memory recall. A small number of them turned to alternative medical therapies, such as traditional Chinese medicine and meditation, to improve their memory.

Peripheral neuropathy.

The majority of the survivors claimed that the numbness that resulted from chemotherapy manifested as physical pain that caused disruptions to their daily living. Because neuropathy interferes with their daily living, the survivors were afraid that this effect would be permanent, and they were skeptical about recovering from the adverse effects.

“It is painful [that] you couldn’t open the [bottle] cap, [and] you couldn’t do so many things. I remembered […] at one stage, splashing water on my face is also painful.”

“I am not that confident […] the nerves take time to recover.”

This resulted in some survivors turning to alternative medical therapies to overcome this adverse effect, and a small number of them attempted to massage the areas of numbness.

“The therapist that I went to, she does a mixture […] of […] Western, […] Japanese, [and] a little bit [of] traditional Chinese medicine.”

Fatigue.

Most of the survivors also complained that they experienced fatigue, especially after chemotherapy. They admitted that chemotherapy made them tired and very sleepy. However, they also acknowledged that this effect might not be significant, because healthy individuals can also get tired. Some survivors claimed that they had to find ways, such as taking afternoon naps, to keep themselves alert, and one survivor mentioned consuming coffee to stay awake.

Emotional, Social, and Spiritual Effects of Cancer Treatment

Fear and sadness were common among survivors. Some survivors were not optimistic about their prognosis, and this negative mindset led them to experience depression and anxiety.

Fear, sadness (uncertainty), and stress.

The fear and uncertainty of the future resulted in a negative outlook on life for many survivors. As they suffered from the adverse effects of chemotherapy and the symptoms of breast cancer, the optimistic survivors grew to accept their fate and lost much hope in life.

“When you first started, you live from cycle to cycle, you can survive cycle to cycle, but then subsequently when it gets worse […], you start living from day to day […], then from day to day, it becomes meal to meal.”

The majority of the survivors agreed that they were constantly under stress and did not have time to relax. One of the common concerns that arose from the various discussions was the fear of recurrence of their cancer.

Difficulty in coping with distress.

With the variations in advice that they received, many survivors agreed that they were confused about whom to trust, and they had minimal avenues by which they could cope with this emotional distress. Controlling their emotions posed a great challenge to the survivors.

“Initially [my husband kept] telling me […] to stay positive and things like that. I keep on telling him, you are not me, you don’t know how I feel, can you let me [vent] out my feelings or not?”

Religious beliefs and support of family and friends.

The majority of the survivors agreed that support from family and friends was important during their treatment and battle with cancer. For those survivors who did not know how to cope with emotional distress, they turned to religious support; many of them went to healing rooms or turned to prayer in churches or temples.

Post-Treatment Follow-Up: Patient-Related Barriers

Through the discussions, we aimed to establish the factors that might deter survivors from continuation of their treatment or participation in any post–active treatment programs.

Lack of consultation time with specialists.

One common barrier reflected by the majority of the survivors was the issue of time spent with their oncologists. The survivors agreed that most of their questions were left unanswered because of the short consultation time with the oncologists.

“Sometimes [during] the consultation, we do not have that much time to […] talk to the doctor.”

Although lack of time is a concern, many survivors also agreed that generally this was not a significant barrier to their follow-up care, because there were other allied health care professionals to turn to who could answer their queries.

“I find that when I talk to the oncologist and the doctor, I am a bit rush, but I find talking to the pharmacist, the time that I don’t have to see the doctor right, I go and see the pharmacist just before the chemo, and I think that talking to the pharmacist, I have more time.”

Unplanned hospitalization.

Some survivors also mentioned the fear of unplanned hospitalization during their follow-up care. Some expressed their fear of diagnostic tests, including blood tests, because these tests may detect other health problems.

“I don’t like to be hospitalized […] because I already have very bad insomnia, even in my house at night I have difficulties sleeping, that is from young, I already have this problem, all the more when I am having this condition, I [find it] harder for me to sleep […] If [I] need to be hospitalized, [I don’t have] to sleep [already].”

Post-Treatment Follow-Up: Health Care System–Related Barriers

Almost all of the survivors expressed their desire to continue their follow-up at the specialized cancer center. These survivors perceived the health care professionals at the cancer center as more knowledgeable in cancer treatment, and they thought that maintenance of treatment records at the cancer center was important. This confidence arose mainly as a result of prior experience with the center and was boosted by the services they received during active treatment.

Generally, the survivors were not confident with community cancer care, especially follow-up care with the community general practitioners (GPs). They perceived the GPs as not adequately knowledgable about cancer treatment, and some of the survivors reflected that they were turned away by GPs when they approached the community clinic for consultation. Thus, many survivors preferred to continue follow-up at the specialized cancer center, even for simple procedures, such as vaccinations.

“I go to the GP, he doesn’t know how to do it […]. They actually turn you off, they say ‘No, I don’t do things like that.’ They turn you all away.”

DISCUSSION

This qualitative study was conducted to gain an in-depth understanding of the health concerns identified by breast cancer survivors in Asia and the barriers that would hinder them from optimal care during survivorship. Although much of the perspectives carry similarities with known literature,6,7 this study has identified a number of unique perspectives, particularly with the way survivors in Asia manage and cope with survivorship issues.

Survivors were overwhelmed by symptoms, including cognitive impairment, fatigue, and peripheral neuropathy, and they expressed concerns that these toxicities would become permanent over time. Although neurologic complications (both peripheral neuropathy and cognitive impairment) are significant after cancer treatment, it is clear to us that the survivors are not aware of strategies for coping with the physical effects of these complications. Thus, many of them resorted to complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). CAM is believed to have positive effects on psychological relief.8 One study found that Asian survivors believe that gingko biloba may have beneficial effects to reverse cancer-related cognitive toxicity.9 There is minimal evidence of the effectiveness of such CAM treatments to provide psychological symptom relief in cancer survivors.10 Yet, our participants expressed their eagerness and willingness to try these unconventional therapies to attain relief. These findings highlight the importance of conducting studies to evaluate specific CAM therapies that could resolve cancer-related symptoms.

Asians are generally influenced by culture and beliefs, and it is apparent that peers and family play a major role in the road of cancer recovery among Asians. This finding is consistent with a number of studies conducted among Asian survivors who observe the importance of adequate family support on the road to cancer recovery. Previous studies have shown that Asians uphold family values and remain conservative and dependent upon the support of friends and family members during critical illnesses.11,12 This is in contrast to a group of young breast cancer survivors in the United States, of whom most stated that they had lost family support or even interaction with their family members.13 Although the current guidelines from the Institute of Medicine on the cancer survivorship care plan do not address how family and peer support should be incorporated into a patient’s care plan, it is essential that survivorship programs implemented in Asia ensure sufficient involvement from family and peers. Such cultural differences between the Asian and Western societies should not be ignored.

We have also identified several patient- and health care–related barriers that are specific to Asian breast cancer survivors who participate in survivor care programs. Patient-related barriers were mainly personal in nature, such as the fear of unplanned hospitalizations or the receipt of inappropriate treatments. These barriers could be explained in part by the poor health literacy of our survivors.14 Past studies have also suggested that Asian survivors who have migrated to the Western world suffer from cultural barriers that lead to poorer outcomes in survivorship care.15 This highlights the importance of taking into account cultural sensitivity when survivorship programs for Asian breast cancer survivors are designed.

ASCO has recently provided recommendations to guide the management of breast cancer survivorship, which emphasize the role of a primary care provider to deliver survivorship care.16 Given the wide disparity of health care resources among different Asian countries, the ASCO standards must be carefully tailored and adopted, particularly in resource-limited countries. In Asia, confidence remained an issue in this context; many of the breast cancer survivors noted that primary care clinicians were not adequately trained to handle the complexity of their conditions. This issue has also been greatly discussed in the literature within the Western context.17 As the breast cancer burden in Asia increases, it might not be feasible to solely depend on the specialized cancer center to adequately meet the needs of these survivors. A few strategies could be implemented to improve the seamless transition of care between the specialized cancer center and the GPs: greater use of electronic resources, such as web-based survivorship care plans, to ensure that care plans are accessible by GPs; improvement in the knowledge and confidence of GPs about care of cancer survivors by using different platforms, including didactic workshops, certification courses, and distance learning; and safe distribution of some services to a multidisciplinary team that comprises primary care providers and allied health professionals, such as nurses, pharmacists, and medical social workers (under a shared model) to provide holistic care for Asian cancer survivors. Currently, a randomized controlled trial is ongoing to evaluate the effectiveness of a standardized multidisciplinary survivorship program that is culturally adapted for Asian breast cancer survivors who have completed chemotherapy.3 The results from this study will drive the directions of survivorship care and provide insights into how such a structured program might be implemented on a larger scale and on a national level.

There are a few limitations to this qualitative study. Given that all of the participants of the focus group discussions were breast cancer survivors, findings of this study may not be generalizable to other cancer populations. Furthermore, participants of these focus groups were relatively highly educated; hence, their perspectives may not represent women who are less educated.

In conclusion, with the increase of cancer survivors in the next few decades, cancer survivorship is recognized as an important issue on a global scale. As interest in cancer survivorship grows in Asia, a more comprehensive understanding of Asian breast cancer survivors is needed to create transitional programs that suit their needs. Our data suggest that breast cancer survivors in Asia are still unfamiliar with the term survivorship and have a multitude of physical health and psychological issues to address to allow the transition to normalcy. Budding survivorship programs in Asia must take survivor perspectives into consideration to ensure that survivorship care is more fully optimized within the community.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Cancer Centre Community Cancer Fund Grant No. COMCF-YR2014-NOV-SD3 Call 2014 and Pretty in Pink 2014 Event.

Both A.C. and Z.K.L. contributed as first co-authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Alexandre Chan, Terence Ng, Yee Pin Tan, Gilbert Fan

Collection and assembly of data: Alexandre Chan, Zheng Kang Lum, Terence Ng, Tewodros Eyob, Xiao Jun Wang, Jung-woo Chae, Sreemanee Dorajoo, Maung Shwe, Yan Xiang Gan, Yee Pin Tan, Gilbert Fan

Data analysis and interpretation: Alexandre Chan, Zheng Kang Lum, Terence Ng, Rose Fok, Kiley Wei-Jen Loh, Yee Pin Tan, Gilbert Fan

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Alexandre Chan

Honoraria: Merck Sharp & Dohme

Consulting or Advisory Role: Merck Sharp & Dohme

Speakers' Bureau: Merck Sharp & Dohme

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Merck Sharp & Dohme

Zheng Kang Lum

No relationship to disclose

Terence Ng

No relationship to disclose

Tewodros Eyob

No relationship to disclose

Xiao Jun Wang

No relationship to disclose

Jung-woo Chae

No relationship to disclose

Sreemanee Dorajoo

No relationship to disclose

Maung Shwe

No relationship to disclose

Yan Xiang Gan

No relationship to disclose

Rose Fok

No relationship to disclose

Kiley Wei-Jen Loh

No relationship to disclose

Yee Pin Tan

No relationship to disclose

Gilbert Fan

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Cheung YT, Shwe M, Chui WK, et al. Effects of chemotherapy and psychosocial distress on perceived cognitive disturbances in Asian breast cancer patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46:1645–1655. doi: 10.1345/aph.1R408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng T, Toh MR, Cheung YT, et al. Follow-up care practices and barriers to breast cancer survivorship: Perspectives from Asian oncology practitioners. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:3193–3200. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2700-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chan A. Effectiveness of a psychoeducational group (PEG) intervention on supportive care and survivorship issues in early-stage breast cancer survivors who have received systemic treatment. Bethesda, MD, ClinicalTrials.gov, National Library of Medicine, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Attride-Stirling J. Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual Res. 2001;1:385–405. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin PY, Turner BA. Grounded theory and organisational research. J Appl Behav Sci. 1986;22:141–157. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Documet PI, Trauth JM, Key M, et al. Breast cancer survivors’ perception of survivorship. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2012;39:309–315. doi: 10.1188/12.ONF.309-315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fouladi N, Ali-Mohammadi H, Pourfarzi F, et al. Exploratory study of factors affecting continuity of cancer care: Iranian women’s perceptions. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:133–137. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lengacher CA, Bennett MP, Kip KE, et al. Relief of symptoms, side effects, and psychological distress through use of complementary and alternative medicine in women with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33:97–104. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.97-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheung YT, Shwe M, Tan YP, et al. Cognitive changes in multiethnic Asian breast cancer patients: A focus group study. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2547–2552. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kinsel JF, Straus SE. Complementary and alternative therapeutics: Rigorous research is needed to support claims. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2003;43:463–484. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.43.100901.135757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehta KK. Multigenerational relationships within the Asian family: Qualitative evidence from Singapore. Int J Sociol Fam. 2007;33:63–77. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yi C, Chang C: Chang Y: The intergenerational transmission of family values: A comparison between teenagers and parents in Taiwan. J Comp Fam Stud 35:523-545, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruddy KJ, Greaney ML, Sprunck-Harrild K, et al. Young women with breast cancer: A focus group study of unmet needs. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2013;2:153–160. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2013.0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. doi: 10.1177/1078155215587541. Cheung YT, Ong YY, Ng T, et al: Assessment of mental health literacy in patients with breast cancer. J Oncol Pharm Pract 22:437-447, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwok C, Koo FK, D’Abrew N, et al. East meets West: A brief report of a culturally sensitive breast health education program for Chinese-Australian women. J Cancer Educ. 2011;26:540–546. doi: 10.1007/s13187-011-0212-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Runowicz CD, Leach CR, Henry NL, et al. American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology breast cancer survivorship care guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:611–635. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.3809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayer EL, Gropper AB, Neville BA, et al. Breast cancer survivors’ perceptions of survivorship care options. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:158–163. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.9264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]