Abstract

Heterokaryon incompatibility is a cell destruction process that occurs when fungal cells of unlike genotype fuse. In Podospora anserina, autophagy is engaged during cell death by incompatibility and a number of genes are induced at the transcriptional level. These genes are termed idi (induced during incompatibility) genes. Among these is idi-4, a gene encoding a basic leucine zipper (bZIP) factor. IDI-4 displays similarity to the GCN4/cross-pathway control (CPC) factors that control gene expression in response to amino acid starvation in fungi. The overexpression of idi-4 triggers autophagy, leads to cell death, and also increases the expression of a number of idi genes, in particular idi-7, a gene involved in autophagy. Herein, we determined the in vitro target sequence of IDI-4. We have purified the recombinant IDI-4 bZIP domain and show that this 83-amino-acid-long peptide dimerizes in vitro and adopts an α-helical fold. We have then used a systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment procedure to identify the sequence bound by the IDI-4 bZIP domain. The IDI-4 binding site consensus sequence corresponds to the ATGANTCAT pseudopalindrome. IDI-4 binding sites are present in the promoter region of the idi-7 gene, and the bZIP IDI-4 peptide binds to the idi-7 promoter in vitro. The identified IDI-4 consensus binding sequence is very similar to the GCN4/CPC binding site, raising the possibility of an interplay and/or partial functional redundancy between IDI-4 and CPC-type bZIP factors in fungi.

Autophagy is a cellular degradation process conserved in all eukaryotes involving the lysosomal-vacuolar compartment (24). During autophagy, bulk cytoplasm or entire organelles are engulfed in specialized vesicles termed autophagosomes and targeted to the vacuole for degradation. Autophagy allows recycling of macromolecular components and thus represents a mechanism of adaptation to starvation. Autophagy can also occur as a programmed cell death (PCD) mechanism. Autophagic programmed cell death is designated type II PCD, as opposed to apoptotic (type I) PCD (16). The biological importance of autophagy in normal development and disease is becoming increasingly clear, and a number of autophagic cell death mechanisms at the molecular level in a variety of eukaryotic organisms are now being analyzed (3, 15).

In filamentous fungi, when cells of unlike genotype fuse, a cell death reaction occurs and the fusion cells are rapidly destroyed. This cell death reaction is termed heterokaryon incompatibility and is triggered by genetic differences at specific loci (het loci) (7). A given species displays about 10 different het loci, and a genetic difference at any given het locus is sufficient to trigger incompatibility. Although molecular identification of het genes in several fungal species has been achieved, the modalities of cell death execution remain largely elusive. In Podospora anserina, this cell death reaction involves the induction of autophagy and the transcriptional activation of a set of genes termed idi (induced during incompatibility) genes (2, 19). Among them are the idi-6 and idi-7 genes, which encode proteins involved in autophagy. idi-6 is the ortholog of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene prB1 and encodes a vacuolar protease, while idi-7 is the ortholog of ATG8 and encodes a protein involved in autophagosome formation (19). All idi genes are also induced by rapamycin, a specific inhibitor of the TOR kinase pathway (4). This finding led to the suggestion that incompatibility triggers an autophagic cell death program controlled by the TOR pathway (4, 19). However, the mechanism of induction of this autophagic cell death program remains largely unknown.

We have recently characterized idi-4, a novel idi gene encoding a basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor (5). The 25-kDa IDI-4 protein displays a putative N-terminal trans-activation domain and a C-terminal bZIP domain. The IDI-4 bZIP domain displays similarity to the jblA Aspergillus nidulans bZIP factor (20) and also to the fungal cross-pathway control (CPC) bZIP factors of the GCN4 type which control amino acid metabolism in response to nutrient starvation (5). Putative idi-4 orthologs exist in a number of filamentous ascomycetes including Neurospora crassa, Magnaporthe grisea, and Fusarium graminearum. jblA and idi-4 are both induced by amino acid starvation; they are not GCN4/CPC orthologs but are likely to represent an independent gene family of fungal bZIP factors (5, 20). idi-4 is induced at the transcriptional level during cell death by incompatibility but also by rapamycin and various stress conditions. The constitutive or inducible overexpression of idi-4 leads to cell death. The idi-4-induced cell death mimics several aspects of cell death by incompatibility. In particular, we found that the overexpression of idi-4 induces autophagy. Then, at least two idi genes, namely idi-2 and idi-7, are induced upon increased expression of idi-4, suggesting that these genes are targets (either direct or indirect) of idi-4 (5). The fact that the overexpression of idi-4 induces cell death indicates that the genes responsible for execution of the cell death program are among the targets of this bZIP factor. In order to further characterize this cell death program and to understand how it is regulated, we set out to characterize the IDI-4 target DNA sequence. We have defined the in vitro DNA-binding specificity of IDI-4 by using a random selection approach (systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment [SELEX]). We find that the IDI-4 bZIP domain binds a pseudopalindromic ATGANTCAT sequence closely resembling the GCN4/CPC binding site and binds to the idi-7 promoter sequence in vitro.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression and purification of the IDI-4 bZIP domain.

The region encoding the IDI-4 protein from residue 171 to 252 was amplified by PCR with oligonucleotides ZIP (5′ATCATATGACCAAGAAACGTCCTCTGCCTG 3′) and 6His (5′TCAGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGATCCTTCTTCCCCGTTGTC 3′) as primers. The 6His primer allows introduction of a six-histidine tag at the C terminus of the protein. The PCR product was then cloned in the pGEM-T vector (Promega), sequenced, and subcloned as a NdeI-NotI fragment in the pET-24a vector (Novagen). The resulting pET-24a-bZIP IDI-4 vector was introduced into an Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) pLysS recipient strain (Novagen). For expression of the bZIP IDI-4 protein, a 50-ml overnight culture was used to inoculate 1 liter of 2YT medium containing 34 μg of chloramphenicol/ml and 100 μg of kanamycin/ml. The culture was incubated with agitation at 37°C until the optical density at 600 nm reached 0.5; expression was then induced by adding 1 mM of IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside). After 2 h, cells were recovered by centrifugation for 10 min at 3,000 × g, and the cell pellet was frozen at −20°C. For purification, the cells were lysed in 150 ml of buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 0.7 M NaCl, and 5 mM imidazole) and centrifuged for 20 min at 12,000 × g. Ten milliliters of TALON resin slurry (BD Bioscience Clontech) equilibrated in buffer A was added to the supernatant fraction. The crude cell extract was incubated with the resin for 90 min at 4°C with gentle agitation. The resin was then applied to a gravity column and washed with 200 ml of buffer A. The protein was eluted in 25 ml of buffer B (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8] and 150 mM NaCl). This protocol yielded about 3 mg of IDI-4 bZIP protein per liter of bacterial culture. The protein was pure, as judged by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) followed by Coomassie blue or silver nitrate staining.

Glutaraldehyde cross-linking.

For glutaraldehyde cross-linking, the bZIP IDI-4 protein at 10 μM in 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 8) was incubated for various times with either 0.01 or 0.2% glutaraldehyde at 20°C. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie blue staining.

Circular dichroism.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra at 20°C in a solution containing 150 mM NaCl and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) were determined by using a Jasco 810 spectropolarimeter with quartz cells of 0.1 or 1 cm path length. Protein concentrations ranged from 0.15 to 15 μM. Deconvolution of the spectra was performed with the K2d program, available at http://www.embl-heidelberg.de/∼andrade/k2d.html.

SELEX procedure.

For the SELEX procedure, a library of 68-bp double-stranded random sequence oligonucleotides was generated by PCR with 5 ng of the N30 oligonucleotide [5′CGGGATCCTAAGTAGGTAG(N)30GACGTTAGCTATCTAGAGC 3′] as the template and 2 μg of oligonucleotide ADBam (5′ CGGGATCCTAAGTAGGTAG 3′) and 2 μg of oligonucleotide ADXba (5′GCTCTAGATAGCTAACGTC 3′) as primers in a reaction volume of 100 μl. PCR conditions were 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 58°C, and 1 s at 72°C for 25 cycles. The PCR products were analyzed on a 4% NuSieve FMC agarose gel. One microgram (20 pmol) of the 68-bp double-stranded random sequence oligonucleotide library was then incubated at 25°C in a volume of 100 μl with 10 pmol of purified IDI-4 bZIP protein in a solution containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) and 100 mM NaCl with 1 mg of bovine serum albumin (BSA) ml−1 and 10 μg of poly(dI-dC) ml−1. After 30 min, 2 μl of TALON metal affinity resin suspension (BD Bioscience Clontech) equilibrated in a solution containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) and 100 mM NaCl was added to the reaction mixture. Incubation was prolonged for 10 min, and then the reaction mixture was centrifuged for 1 min at 2,000 × g, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was washed four times in a 500-μl solution containing 50 mM Tris-HCl and 100 mM NaCl. The protein was then eluted from the resin with a 50-μl solution of 100 mM imidazole, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 100 μg of BSA ml−1, and 1 μg of poly(dI-dC) ml−1. The reaction was centrifuged for 1 min at 2,000 × g, and the supernatant was collected. Five microliters of the eluted fraction was amplified by PCR for 30 cycles in the same conditions as described above. The PCR product was ethanol precipitated, and 300 ng of the PCR product was submitted to a second SELEX cycle with the same conditions as above. Two more SELEX cycles were performed with the same conditions except that only 1 μl of a 100-fold dilution of the eluted fractions was used as the template in a 25-cycle PCR. After the fourth cycle, the PCR products were cloned in the pGEM-T vector (Promega), and inserts of 71 independent clones were sequenced.

Gel retardation assays.

For gel retardation experiments, probes were obtained with pGEM-T-cloned SELEX sequence as the template and oligonucleotides ADBam and ADXba as primers. The 68-bp fragment was gel purified on 4% NuSieve FMC agarose gels, digested with BamHI and XbaI, and labeled with [α-32P]dCTP (10,000 mCi/ml; Amersham) by using Klenow enzyme. Specific activity was about 100,000 cpm per ng of DNA. Binding reactions were performed for 15 min on ice in a volume of 10 μl with 0.2 ng of probe (20,000 cpm), 10 to 20 ng of purified bZIP IDI-4 protein in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 150 mM NaCl, 20 ng of poly(dI-dC) μl−1, and 0.3 μg of BSA μl−1. Electrophoresis was performed in a Miniprotean II apparus (Bio-Rad) on a 5% acrylamide gel in 1× Tris-borate-EDTA at 4°C for 1 h at 100 V. After electrophoresis, the gels were dried for 45 min at 80°C under a vacuum. The probe corresponding to the idi-7 promoter or to the mutated idi-7 promoter was obtained by PCR with oligonucleotides IDI7.5 (5′ GCCCTGATGATTCATACCGGGAC 3′) and IDI7.3 (5′ TCAAAGGTGAATCATATGGGGCG 3′) or IDI7.5 M (5′ GCCCTGATGCTGCATACCGGGAC 3′) and IDI7.3 M (5′ TCAAAGGTGCAGCATATGGGGCG 3′) and the p1004GFP-idi-7 plasmid as the template (19). The positions of the introduced mutations are underlined. The concentration of unlabeled dNTPs was 50 μM. Five microliters of [α-32P]dCTP was added in a final reaction mixture volume of 20 μl. The specific activity of the probe was about 30,000 cpm per ng of DNA. Binding and electrophoresis were performed as described above except that 6.5% acrylamide gels were used and the process ran for 90 min at 150 V. Competitor fragments corresponded to unlabeled PCR products. The 249-bp P. anserina genomic DNA fragment used as a nonspecific competitor was obtained with oligonucleotides 173 (5′ CGCCATCGACTTCGCCTATG 3′) and 246 (5′ TGCTGGCTGAGGGTGTTGTTG 3′). In the competition experiments, the bZIP IDI-4 protein was used at 250 nM.

Sequence analyses.

Secondary structure prediction of the bZIP IDI-4 peptide were performed by using the GORIV method, available at http://pbil.ibcp.fr. Tertiary structure prediction was performed by using the Geno3D program, available at http://pbil.ibcp.fr. For identification of a consensus binding site, the sequences were analyzed with the Multiple EM for Motif Elucidation (MEME) program, http://meme.sdsc.edu/meme/website/meme.html (1). The sequences of the idi gene promoters or of random genomic P. anserina sequences were analyzed for occurrence of the putative IDI-4 binding site by using the FUZZNUC program at http://bioweb.pasteur.fr/seqanal/interfaces/fuzznuc.html. Genomic P. anserina sequences were recovered at http://podospora.igmors.u-psud.fr/.

RESULTS

Purification of the IDI-4 bZIP domain.

In order to identify the IDI-4 binding sequence, we decided to express the DNA binding domain of IDI-4 in E. coli. The expressed peptide is 83 amino acids long and encompasses the C-terminal end of the IDI-4 protein (Fig. 1). The peptide starts 20 amino acids upstream of the conserved bZIP domain and is tagged with six-histidine residues at its C terminus. Its predicted molecular mass is 10.7 kDa. The bZIP IDI-4 domain was expressed at reasonably high levels as a soluble protein in E. coli and could be purified to homogeneity in a single-affinity chromatography step (Fig. 2A). The purified protein displayed an apparent molecular mass of about 12 to 13 kDa as judged by SDS-PAGE. Slightly aberrant migrations in SDS-PAGE have been described for other bZIP domains and may be due to charge clustering in the basic region of the sequence. In some preparations, a minor band of higher mobility was detected; this band is likely to correspond to a degradation product truncated at the N-terminal end, as this region is predicted to be unstructured and is thus potentially very sensitive to proteolysis.

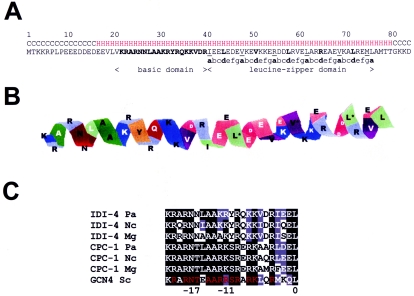

FIG. 1.

Sequence and structure prediction of the IDI-4 bZIP domain. (A) Sequence and secondary structure prediction of the 83-amino-acid-long bZIP IDI-4 peptide expressed in E. coli. The basic domain is shown in boldface characters. In the leucine-zipper domain, positions a of the heptad repeats are underlined and positions d are shown in boldface type. Secondary structure predictions are shown above the protein sequence and were performed by the GORIV (Garnier/Osguthorpe/Robson) method at the Network Protein Sequence Analysis server (http://npsa-pbil.ibcp.fr/). C, random coil; H, helical. (B) Homology-based structure prediction of the basic domain and leucine-zipper domain of IDI-4 performed with the Geno3D program server (http://geno3d-pbil.ibcp.fr). The structure was modeled based on the structure of the GCN4 bZIP domain; the last two heptad repeats were not modeled, because the IDI-4 and GCN4 sequences diverge in that region. Positions a of the heptad repeats are marked with asterisks. The sequence is predicted to adopt an uninterrupted α-helix with a hydrophobic interface. (C) Sequence alignment of the basic domain of various fungal bZIP factors of the IDI-4 type and of the GCN4/CPC type. In this numbering, position 0 is the first leucine of the zipper domain. Amino acid positions that make DNA contacts in Gcn4p are shown in red type. Pa, Podospora anserina; Nc, N. crassa; Mg, M. grisea; Sc, S. cerevisiae.

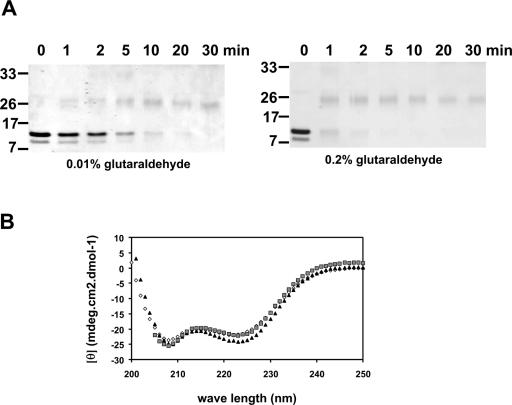

FIG. 2.

The recombinant IDI-4 bZIP domain forms a dimer and adopts an α-helical fold in vitro. (A) Glutaraldehyde cross-linking of the bZIP IDI-4 peptide. Purified recombinant bZIP IDI-4 peptide was incubated with two different concentrations of glutaraldehyde for various times and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Note the formation of a covalently linked bZIP IDI-4 dimer and the disappearance of the monomer. (B) CD spectrum of purified bZIP IDI-4 peptide, recorded at different protein concentrations in a solution of 150 mM NaCl and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) at 20°C. White diamonds, 15 μM; black triangles, 1.5 μM; grey squares, 0.15 μM. The spectrum shows two minima, at 208 and 222 nm, which are typical of α-helical secondary structures. Also note that the mean residue ellipticity (θ) does not vary significantly with decreasing protein concentration, indicating that the peptide does not unfold upon dilution.

Recombinant bZIP IDI-4 forms a dimer and adopts an α-helical fold in vitro.

bZIP proteins bind DNA as dimers, and each monomer forms a single uninterrupted 55- to 65-amino-acid-long α-helix (6). The C-terminal leucine zipper region allows dimerization of the helices as parallel coils. The basic domains form a pair of tweezers which contact DNA on each side of the double helix. Typical bZIP domains, such as those of fos, jun, and GCN4, are unstructured in their monomeric form and adopt an α-helical fold only upon dimerization. bZIP domains thus unfold upon dimer dissociation induced by dilution (26, 27).

In order to determine whether the bZIP IDI-4 peptide forms a dimer in vitro, we submitted the purified protein to glutaraldehyde cross-linking. The bZIP IDI-4 peptide was incubated for various times with either 0.01 or 0.2% glutaraldehyde and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. We found that over time, the amount of monomer decreases while a band appears at about 26 kDa, presumably corresponding to the covalently linked dimer. The experiment strongly suggests that bZIP IDI-4 peptide dimerizes in vitro.

Secondary structure prediction programs and homology-based three-dimensional modeling suggest that the IDI-4 bZIP domain adopts an α-helical fold (Fig. 1). We have analyzed the secondary structure content of the purified bZIP IDI-4 protein at 15 μM by using CD. The CD spectrum of the bZIP IDI-4 peptide displays two minima, at 208 and 222 nm, which are characteristic of α-helical secondary structures (Fig. 2). Deconvolution of this spectrum suggests that about 60% of the bZIP IDI-4 residues display an α-helical conformation. The CD spectrum was also recorded after a 10- or 100-fold dilution. In contrast to that which has been reported for the GCN4 bZIP domain, the mean residue ellipticity was not significantly affected by dilution (26, 27). This result indicates that in contrast to the GCN4 bZIP domain, the IDI-4 bZIP domain does not unfold at low protein concentrations (<1 μM). This observation suggests that the Kd for dimer formation is lower for the IDI-4 bZIP domain that for the GCN4 bZIP domain.

Together, these experiments suggest that the purified IDI-4 bZIP domain adopts its native α-helical fold and forms a stable dimer in vitro. The purified bZIP IDI-4 peptide thus appears well suited for functional studies.

Identification of the in vitro consensus binding site of IDI-4 by SELEX.

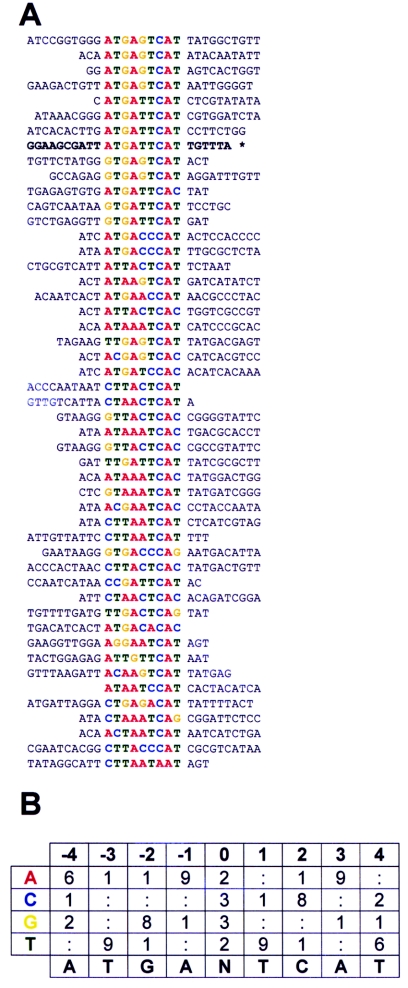

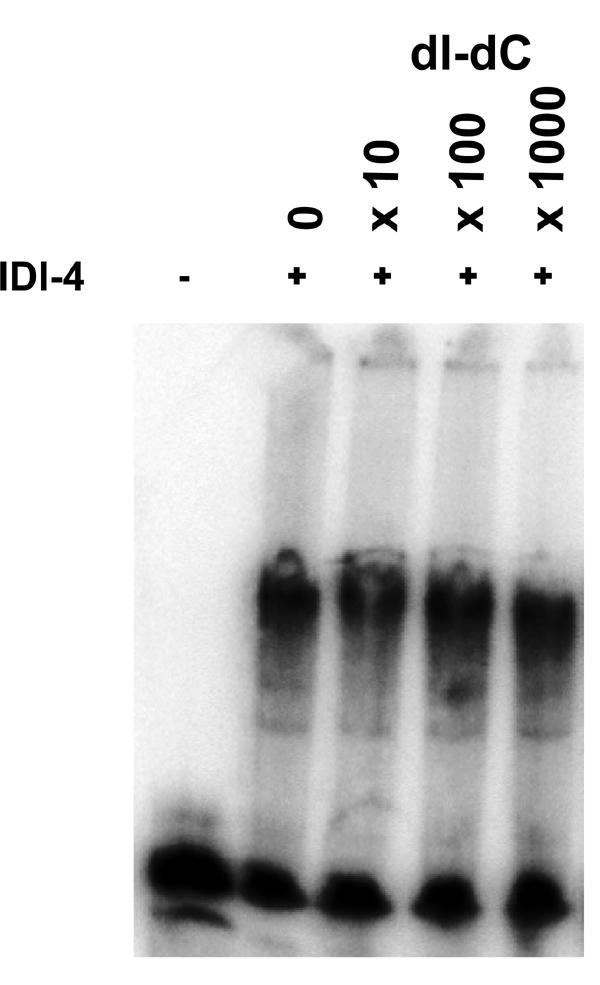

We chose to identify the in vitro consensus binding sequence of the bZIP IDI-4 peptide by the SELEX procedure. This reiterative technique allows the identification of the sequence bound by a particular protein (or nucleic acid) from a pool of random-sequence DNA or RNA oligonucleotides. We generated a library of 68-bp-long double-stranded oligonucleotides displaying a random sequence segment of 30 bp flanked by 19 bp of adaptor sequences. This library was incubated with purified bZIP IDI-4 protein, and the sequences bound by the protein were amplified by PCR (see Materials and Methods). After four SELEX cycles, the amplified 68-bp sequences were used as probes in a gel shift experiment with the purified bZIP IDI-4 protein, and a specific shift was detected (data not shown). We concluded that sequences specifically bound by IDI-4 had been selected and decided to clone the amplified sequence. The sequences of 71 independent SELEX clones were determined and compared by using the MEME program (1) in order to identify common motifs. The MEME program retained 49 clones to define a 9-bp consensus motif. This motif is ATGANTCAT, a pseudopalindromic sequence with two TGA half-sites. The motif is highly statistically significant (E value, 1.3e-23). In other words, the probability of random occurrence of these motifs in our data set is very low. A simplified position-specific scoring matrix for this motif is given in Fig. 3 together with the sequences of 49 retained clones. In this motif, the two TGA half-sites appear critical. To a lesser extent, the A/T at positions −4 and +4 are also significant. In contrast to this data set, there appears to be no significant constraint on the central base in position 0. In order to verify that the identified motif is indeed bound by the bZIP IDI-4 peptide, we used one SELEX clone (clone 23, shown in boldface type in the list in Fig. 3) as a probe in gel shift experiments. We found that the bZIP IDI-4 peptide is able to bind specifically to this SELEX clone (Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

Sequence of the SELEX clones. (A) Sequence of the 49 SELEX clones aligned by the MEME program and listed according to their similarity with the SELEX consensus. The clone used in gel shift experiment (clone 23) is marked by an asterisk. (B) Simplified position-specific scoring matrix for the motif generated from the alignment given in panel A and the 9-bp-long bZIP IDI-4 consensus binding site. MEME motifs are represented by position-specific probability matrices that specify the probability of each base appearing at each position. The base probabilities are multiplied by 10 and rounded to the nearest integer. Each zero has been replaced by a colon (:) for readability.

FIG. 4.

Recombinant bZIP IDI-4 binds a SELEX clone in vitro. A gel retardation experiment was performed with purified recombinant bZIP IDI-4 peptide. Purified bZIP IDI-4 protein was mixed with a 32P-labeled 79-bp fragment corresponding to SELEX clone 23 (containing the ATGANTCAT sequence) used as a probe. In the first lane, the peptide was omitted. In the subsequent lanes, increasing amounts of nonradioactive nonspecific competitor [poly(dI-dC)] were included in 10-, 100-, or 1000-fold excess over the unlabeled probe.

The SELEX procedure allowed us to identify the ATGANTCAT pseudopalindrome as the IDI-4 consensus binding sequence. The palindromic nature of the consensus sequence was clearly expected based on the fact that bZIP factors bind DNA as dimers. The consensus binding site is very similar to the GCN4 consensus binding sequence (ATGACTCAT) (18).

The promoter of idi-7 contains potential bZIP IDI-4 binding sites.

In a previous study, we found that increased expression of IDI-4 induces transcription of idi-2 and idi-7 (5). We analyzed the sequences of the idi-2 and idi-7 promoters for the presence of potential IDI-4 binding sites. One thousand five hundred base pairs of sequence upstream of the idi-2 and idi-7 transcription initiation sites were analyzed for the presence of sequences resembling the IDI-4 consensus binding site. The idi-7 promoter displays a perfect potential IDI-4 binding site at position −383 (ATGATTCAT) and an additional potential IDI-4 site with a single mismatch at +4 starting at position −203 (ATGATTCAC) (Fig. 5). In the idi-2 promoter sequence, no perfect IDI-4 sites were found, but a potential IDI-4 site with a single mismatch was found (ATCATTCAT; position −129). In both promoters, additional potential sites with two mismatches are found. To estimate the occurrence of ATGANTCAT sequences in the P. anserina genome, we scanned 1 Mb of genomic P. anserina sequence for the presence of ATGANTCAT sites. The exact consensus sequence had a mean distribution of 1 in 92,060 bp and had 1 in 3,821 or 1 in 295 bp when allowing one or two mismatches, respectively. The promoter sequences of all of the other known idi genes were analyzed. No perfect or single-mismatch IDI-4 binding sequences were found.

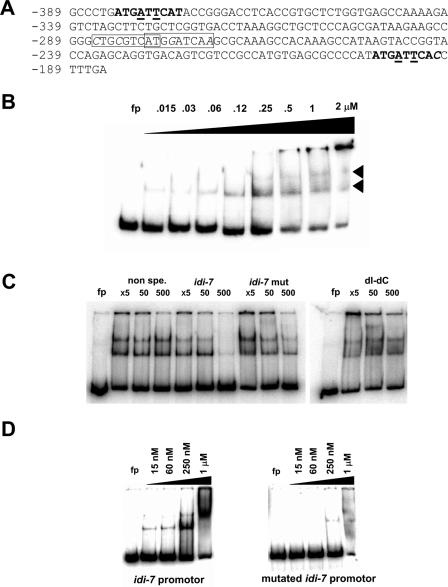

FIG. 5.

bZIP IDI-4 binds to the idi-7 promoter in vitro. (A) Sequence of the fragment of the idi-7 promoter used in the subsequent gel retardation experiments. Numbering is given from the transcription initiation site. The sequences were analyzed for the presence of motifs matching the IDI-4 consensus binding sites. A perfect IDI-4 motif found at position −383 and a single-mismatch IDI-4 motif at position −203 are shown in boldface characters. Positions of the mutations introduced in the idi-7 promoter fragment are underlined (see below and text). Two overlapping double-mismatch IDI-4 motifs (starting at positions −286 and −279) are boxed. Mismatches to the IDI-4 consensus are italicized. (B) Gel retardation assay performed with a 205-bp fragment of the idi-7 promoter as a probe and increasing amounts of bZIP IDI-4 protein. In the first lane, the bZIP IDI-4 peptide has been omitted. The two observed shifted bands are marked by arrowheads. fp, free probe. (C) Gel retardation assays using a 32P-labeled 205-bp fragment of the idi-7 promoter as a probe and nonradioactive competitors. Increasing amounts of nonradioactive competitors were included in 5-, 50-, or 500-fold excess over the unlabeled probe. Competitors were either a 249-bp P. anserina DNA fragment lacking perfect, single-mismatch, or double-mismatch IDI-4 motifs (non spe.), the unlabeled 205-bp idi-7 promoter fragment (idi-7), or a mutated form of the 205-bp idi-7 promoter fragment mutated on both half-sites of the perfect and single-mismatch IDI-4 motifs (idi-7 mut) or poly(dI-dC) (dI-dC). fp, free probe. (D) Gel retardation assays using either the 205-bp fragment of the idi-7 promoter or the mutated form of the idi-7 promoter as a probe and increasing amounts of bZIP IDI-4 protein. fp, free probe.

Based on this analysis, idi-7 is a prime candidate to be a direct IDI-4 target gene.

bZIP IDI-4 binds to the idi-7 promoter in vitro.

In order to determine whether IDI-4 could indeed bind to the potential sites found in the idi-7 promoter, we used a 205-bp fragment from the idi-7 promoter (positions −389 to −185) as a probe in gel retardation experiments. We found that the bZIP IDI-4 leads to a mobility shift when incubated with this fragment. At high IDI-4 bZIP peptide concentrations (0.25 μM and higher), two bands are detectable (Fig. 5B). These two distinct complexes might reflect the existence of two IDI-4 binding sites, presumably the detected perfect and single-mismatch IDI-4 motifs (Fig. 5A). At high protein concentrations, nonspecific binding also occurred, leading to retention of the probe in the well of the gel.

In order to verify that the observed shifts are specific, we carried out a number of specificity controls. First, we performed competition experiments by using the unlabeled idi-7 fragment and nonspecific competitors (Fig. 5C). The unlabeled 205-bp idi-7 promoter fragment efficiently competed away the labeled probe. An unrelated 249-bp fragment (lacking perfect, single-mismatch, and double-mismatch IDI-4 motifs) or the nonspecific competitor poly(dI-dC) used at the same concentration did not significantly affect the amount of shifted probe (but reduced nonspecific binding). We also created a mutated version of the idi-7 promoter that was affected in both TGA half-sites of the two perfect and single-mismatch IDI-4 binding sites at positions −383 and −203 (ATGCTGCAT and ATGCTGCAC, respectively). This mutated 205-bp idi-7 promoter fragment was less efficient as a competitor than the wild-type idi-7 fragment, but slightly more efficient than poly(dI-dC) or the unrelated 249-bp fragment.

As a second specificity control, we compared the wild-type and mutated idi-7 promoter fragment probes in gel retardation experiments (Fig. 5D). The mutation in the two half-sites of the perfect and single-mismatch IDI-4 motifs strongly decreased IDI-4 binding. However, with the mutated probe, a faint shifted band was observed at a 250 nM concentration of protein. It thus appears, as suggested by the competition experiments reported above, that the mutated fragment can still be bound by IDI-4, but with a much lower affinity. It is possible to speculate that the overlapping double-mismatch IDI-4 motifs (position −286 to −271) might be responsible for this low-affinity binding when the perfect and single-mismatch sites are mutated.

We conclude from these experiments that the bZIP IDI-4 protein specifically binds to the idi-7 promoter in vitro. The presence of two distinct shifts suggests that bZIP IDI-4 binds the perfect and single-mismatch IDI-4 motifs found at positions −383 and −203.

DISCUSSION

Cell death by incompatibility in fungi represents a valuable model for the study of programmed cell death in lower eukaryotes. In P. anserina, this cell death reaction is characterized by the transcriptional activation of idi genes. This transcriptional program is under the control of the TOR pathway and the bZIP IDI-4 transcription factor (4, 5). Herein, we characterize the IDI-4 binding sequence and we identify the idi-7 autophagy gene as a likely direct target of IDI-4. Our study further establishes IDI-4 as a direct regulator of the autophagic process in filamentous fungi. The present work opens the way for the identification of the IDI-4 target genes which compose the autophagic cell death execution program.

The identified IDI-4 consensus binding sequence corresponds to the ATGANTCAT pseudopalindrome. This sequence is very similar to the binding sequence of the yeast bZIP GCN4 factor (8, 18) and of its orthologs in filamentous ascomycetes. The yeast GCN4 factor is a master regulator of gene expression and controls the cellular response to amino acid starvation (9). GCN4 binds the ATGACTCAT sequence in vitro (18), and the structure of the GCN4 dimer bound to its cognate site has been determined (6, 11, 12). Eleven of the 13 residues known to be involved in DNA contacts in GCN4 are strictly conserved or similar in IDI-4. This fact readily explains why the GCN4 and IDI-4 DNA-binding site are so similar. The difference between the IDI-4 and GCN4 binding sites resides in the fact that we found no significant constraint on the central base of the pseudopalindrome in the case of IDI-4. The only two positions for which IDI-4 and GCN4 differ by nonconservative changes in the basic DNA-binding domain are positions −11 and −17 (position 0 is the first leucine of the dimerization domain) (Fig. 1). Position −17 is a threonine in GCN4 (and GCN4 orthologs in filamentous fungi). This residue makes contacts with the phosphate backbone near the centre of the binding site (6, 11, 12). An asparagine residue is found at position −17 in the IDI-4 basic domain (Fig. 1). Interestingly, it has been shown that in GCN4, mutation of the −17 threonine residue to an asparagine increases the GCN4 binding register and decreases the constraint on the central base of the pseudopalindrome (21). This difference at position −17 could therefore be the structural basis of the difference in DNA-binding specificity between IDI-4 and GCN4. The conservation in the basic DNA-binding domain between IDI-4 and its putative orthologs in other filamentous ascomycetes is strong. It can thus be proposed that other fungal bZIP factors of the IDI-4-type might display the same specificity as IDI-4.

Our in vitro analyses suggest that the IDI-4 dimer is very stable; it withstands dissociation at concentrations below the micromolar range. The IDI-4 dimer also resists thermal denaturation at up to 85°C (S. J. Saupe, unpublished data). This high stability compared to GCN4 might be due to the fact that the leucine zipper of IDI-4 is composed of five heptad repeats instead of four. In addition to the hydrophobic residues at positions a and d of the heptad repeats, the vast majority (20 of 25) of the other residues of that region are charged. Salt bridges between these residues are likely to contribute greatly to the overall stability of the IDI-4 dimer. This stability might have important functional implications, as active dimers could form even at low cellular IDI-4 protein concentrations.

We have previously pointed out similarities between the IDI-4 and the GCN4/CPC-type bZIP factors (5, 20). Both IDI-4 and GCN4 can be induced by amino acid starvation and rapamycin, and both factors participate in the control of the induction of autophagy (4, 5, 14, 17, 22, 23). The present work shows that these two factors also bind remarkably similar sequences. Thus IDI-4 and GCN4/CPC-type factors might have not only common upstream regulators, but also common downstream targets. The bZIP IDI-4 domain can bind cross-pathway control recognition elements (CPREs) in vitro. Several fungal CPC factors display CPREs in their promoters. These CPREs allow positive autoregulation but might also represent potential targets for IDI-4 type factors (10, 13, 25). Our previous analyses have shown that inactivation of IDI-4 does not prevent induction of cell death by incompatibility and induction of idi genes (5). This observation indicates that transcriptional induction of cell death genes during incompatibility is redundantly mediated. The P. anserina CPC ortholog represents a prime candidate as an auxiliary factor mediating induction of idi genes and autophagy during incompatibility. In vivo studies are now required to address the possibility of a partial functional redundancy and/or interplay between IDI-4 and the P. anserina CPC ortholog.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bailey, T. L., and C. Elkayn. 1994. Fitting a mixture model by expectation maximization to discover motifs in biopolymers. Proc. Int. Conf. Intell. Syst. Mol. Biol. 2:28-36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bourges, N., A. Groppi, C. Barreau, C. Clave, and J. Begueret. 1998. Regulation of gene expression during the vegetative incompatibility reaction in Podospora anserina. Characterization of three induced genes. Genetics 150:633-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuervo, A. M. 2004. Autophagy: in sickness and in health. Trends Cell Biol. 14:70-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dementhon, K., M. Paoletti, B. Pinan-Lucarre, N. Loubradou-Bourges, M. Sabourin, S. J. Saupe, and C. Clave. 2003. Rapamycin mimics the incompatibility reaction in the fungus Podospora anserina. Eukaryot. Cell 2:238-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dementhon, K., S. J. Saupe, and C. Clave. 2004. Characterization of IDI-4, a bZIP transcription factor inducing autophagy and cell death in the fungus Podospora anserina. Mol. Microbiol. 53:1625-1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellenberger, T. E., C. J. Brandl, K. Struhl, and S. C. Harrison. 1992. The GCN4 basic region leucine zipper binds DNA as a dimer of uninterrupted alpha helices: crystal structure of the protein-DNA complex. Cell 71:1223-1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glass, N. L., and I. Kaneko. 2003. Fatal attraction: nonself recognition and heterokaryon incompatibility in filamentous fungi. Eukaryot. Cell 2:1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill, D. E., I. A. Hope, J. P. Macke, and K. Struhl. 1986. Saturation mutagenesis of the yeast his3 regulatory site: requirements for transcriptional induction and for binding by GCN4 activator protein. Science 234:451-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinnebusch, A. G., and K. Natarajan. 2002. Gcn4p, a master regulator of gene expression, is controlled at multiple levels by diverse signals of starvation and stress. Eukaryot. Cell 1:22-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffmann, B., O. Valerius, M. Andermann, and G. H. Braus. 2001. Transcriptional autoregulation and inhibition of mRNA translation of amino acid regulator gene cpcA of filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Biol. Cell 12:2846-2857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keller, W., P. König, and T. J. Richmond. 1995. Crystal structure of a bZIP/DNA complex at 2.2 Å: determinants of DNA specific recognition. J. Mol. Biol. 254:657-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.König, P., and T. J. Richmond. 1993. The X-ray structure of the GCN4-bZIP bound to ATF/CREB site DNA shows the complex depends on DNA flexibility. J. Mol. Biol. 233:139-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krappmann, S., E. M. Bignell, U. Reichard, T. Rogers, K. Haynes, and G. H. Braus. 2004. The Aspergillus fumigatus transcriptional activator CpcA contributes significantly to the virulence of this fungal pathogen. Mol. Microbiol. 52:785-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kubota, H., T. Obata, K. Ota, T. Sasaki, and T. Ito. 2003. Rapamycin-induced translational derepression of GCN4 mRNA involves a novel mechanism for activation of the eIF2α kinase GCN2. J. Biol. Chem. 278:20457-20460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levine, B., and D. J. Klionsky. 2004. Development by self-digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev. Cell. 6:463-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lockshin, R. A., and Z. Zakeri. 2004. Apoptosis, autophagy, and more. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 36:2405-2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Natarajan, K., M. R. Meyer, B. M. Jackson, D. Slade, C. Roberts, A. G. Hinnebusch, and M. J. Marton. 2001. Transcriptional profiling shows that Gcn4p is a master regulator of gene expression during amino acid starvation in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:4347-4368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oliphant, A. R., C. J. Brandl, and K. Struhl. 1989. Defining the sequence specificity of DNA-binding proteins by selecting binding sites from random-sequence oligonucleotides: analysis of yeast GCN4 protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9:2944-2949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinan-Lucarre, B., M. Paoletti, K. Dementhon, B. Coulary-Salin, and C. Clave. 2003. Autophagy is induced during cell death by incompatibility and is essential for differentiation in the filamentous fungus Podospora anserina. Mol. Microbiol. 47:321-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strittmatter, A. W., S. Irniger, and G. H. Braus. 2001. Induction of jlbA mRNA synthesis for a putative bZIP protein of Aspergillus nidulans by amino acid starvation. Curr. Genet. 39:327-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suckow, M., B. von Wilcken-Bergmann, and B. Muller-Hill. 1993. Identification of three residues in the basic regions of the bZIP proteins GCN4, C/EBP and TAF-1 that are involved in specific DNA binding. EMBO J. 12:1193-1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tallóczy, Z., W. Jiang, H. W. Virgin IV, D. A. Leib, D. Scheuner, R. J. Kaufman, E.-L. Eskelinen, and B. Levine. 2002. Regulation of starvation- and virus-induced autophagy by the eIF2α kinase signaling pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:190-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valenzuela, L., C. Aranda, and A. Gonzalez. 2001. TOR modulates GCN4-dependent expression of genes turned on by nitrogen limitation. J. Bacteriol. 183:2331-2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang, C. W., and D. J. Klionsky. 2003. The molecular mechanism of autophagy. Mol. Med. 9:65-76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang, P., T. G. Larson, C. H. Chen, D. M. Pawlyk, J. A. Clark, and D. L. Nuss. 1998. Cloning and characterization of a general amino acid control transcriptional activator from the chestnut blight fungus Cryphonectria parasitica. Fungal Genet. Biol. 23:81-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weiss, M. A. 1990. Thermal unfolding studies of a leucine zipper domain and its specific DNA complex: implications for scissor's grip recognition. Biochemistry 29:8020-8024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiss, M. A., T. Ellenberger, C. R. Wobbe, J. P. Lee, S. C. Harrison, and K. Struhl. 1990. Folding transition in the DNA-binding domain of GCN4 on specific binding to DNA. Nature 347:575-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]