Abstract

We recently examined a 26-month-old boy with abnormal face, blepharophimosis, hypertelorism, apparently low-set ears, micrognathia, arachnodactyly, talipes equinovarus, and joint contractures. Subsequently he manifested failure to thrive, respiratory infections, and developmental delay. These congenital anomalies and associated findings are consistent with a diagnosis of the Marden-Walker syndrome. He also had mild pyloric stenosis and duodenal bands, not previously reported in this syndrome. This syndrome appears to be an autosomal recessive trait in some families. A summary of findings of the 16 previous published patients is presented.

Keywords: abnormal facial appearance, blepharophimosis, developmental delay, joint contractures, failure to thrive, arachnodactyly, apparently low-set ears

INTRODUCTION

We report on a patient with multiple congenital anomalies and unusual facial appearance consistent with the diagnosis of Marden-Walker syndrome. Our patient had blepharophimosis, hypertelorism, apparently low-set ears, micrognathia, arachnodactyly, talipes equinovarus, and joint contractures. Subsequently he had failure to thrive, respiratory infections, and developmental delay. At age 5 days, he was found to have hypertrophic pyloric stenosis and duodenal bands. To our knowledge, no other patient with the Marden-Walker syndrome is known with hypertrophic pyloric stenosis.

CASE REPORT

This white male was born at 41 weeks of gestation, the third pregnancy of his 21-year-old mother. The first pregnancy terminated in a spontaneous abortion at 12 weeks. An autopsy was not performed. The second pregnancy resulted in a normal girl who was 3 years old at the birth of our patient. The father was a healthy, 27-year-old, white man. The parents were nonconsanguineous. The family history was unremarkable; a stillborn paternal uncle is said to have had aplasia of the bones of the hands, ankles, and shoulders. A paternal first cousin had nonspecific brain damage since birth; he died at age 21 years having spent his entire life in an institution for the mentally retarded.

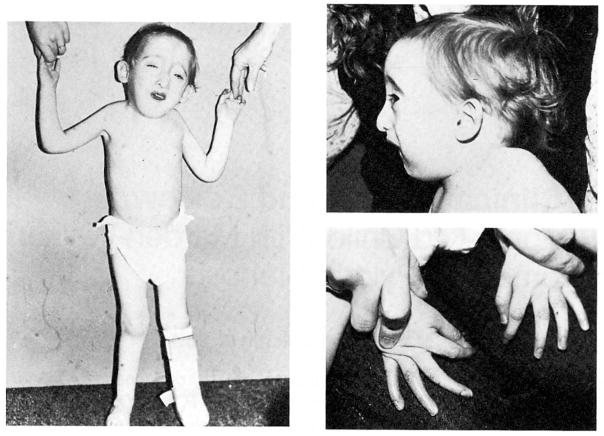

At birth, the infant had a weak cry, was floppy, and became cyanotic but responded to oxygen. The Apgar scores were 6 and 8 at 1 and 5 min, respectively. On physical examination, the infant had a birth weight, length, and occipitofrontal circumference (OFC) of 2.8 kg (10%), 48 cm (15%), and 34.5 cm (30%), respectively. He had multiple congenital anomalies including a small anterior fontanel; bilateral blepharophimosis; apparent hypertelorism; and low-set, abnormally shaped ears; depressed nasal bridge; upturned nose with a deviated septum; small mouth; micrognathia; short neck (Fig. 1); long, slender fingers and toes; bilateral transverse palmar creases; left talipes equinovarus; contractures at the knee, elbow, wrist, hip, and first proximal interphalangeal joints; bilateral cutaneous syndactyly of the second and third toes; strabismus; and mild chordee. Neurologically, he had a good Moro and grasp reflex and decreased muscle tone.

Fig. 1.

Frontal view, profile, and hands of the 26-month-old child with Marden-Walker syndrome.

Radiological studies showed bilateral radial hypoplasia, asymmetry of the orbits, excessively long fingers and toes, left club foot, mild scoliosis, and nonunion of the acromial process. Results of ultrasonography of head, heart, and kidneys were normal.

The patient was transferred to the newborn intensive care nursery because of frequent dusky spells and copious amounts of oral mucus. He did not require ventilation. He was unable to tolerate oral feedings without vomiting nonbilious material; he was fed continuously through an oral tube with only moderate improvement in the vomiting. Although abdominal ultrasonography failed to show any abnormalities, upper gastrointestinal X-ray series indicated hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. On day 10 of life, he was taken to surgery, where the pylorus was found to be 12 mm long, mildly hypertrophic, but less edematous than is usual in pyloric stenosis. The fourth portion of the duodenum was constricted and apparently kinked by several peritoneal bands. The pancreas wrapped about halfway around the duodenum posteriorly just distal to the pylorus. Pyloromyotomy was done with division of the duodenal bands. By the eighth postoperative day, the infant was taking oral feedings well.

Two weeks later, he was readmitted with persistent vomiting and cyanotic/apneic spells lasting for 15–20 sec. The spells occurred mainly during feeding. Nuclear scintogram and upper GI series demonstrated gastroesophageal reflux. He was treated conservatively. At age 5 1/2 months, he had been weaned from the gastrostomy tube and was taking all feedings orally. He no longer experienced apnea, and monitoring was discontinued. Since then, he has had recurrent episodes of otitis media, recurrent constipation, and recurrent bouts of right upper lobe pneumonia that have required several hospitalizations.

At age 26 months, he was seen with right upper lobe pneumonia. His weight, length, and OFC were 9.1 kg, 82 cm, and 46 cm, respectively (all <5th centile). Range of motion at all major joints was improved. Muscle tone was symmetrically decreased in all limbs although less so than at birth. His left foot was in a cast from corrective surgery of his left club foot. Developmental level was at 12 months. He was able to communicate his needs by gestures but was unable to talk. He did not walk but could crawl. Additional tests included ECG, EEG, urinary metabolic screen, serum electrophoresis, thyroid function tests, liver enzymes, and a bone scan, the results of which were all normal.

A gastrocnemius muscle biopsy was examined using routine light microscopy, histochemistry, and electronic microscopy. Fiber size was consistent with age. Many of the muscle fibers demonstrated dropout of the myofibrils and replacement with fibrous tissue. Staining for ATPase, NADH, and SDH gave normal results. Sections analyzed under electron microscopy showed replacement of myofibrils by glycogen particles and massive subsarcolemmal accumulation of glycogen. These results are in agreement with previous investigations [Jaatoul et al, 1982].

DISCUSSION

The Marden-Walker syndrome was described in 1966 as a generalized connective tissue syndrome [Marden and Walker, 1966]. Since then, 16 cases (11 M, 5 F) have been reported [Ealing, 1944; Gellis, 1963; Younessian and Ammann, 1964; Marden and Walker, 1966; Fitch et al. 1971; Temtamy et al, 1975; Passarge, 1975; Simpson and Degnan, 1975; King and Magenis, 1978; Abe et al, 1979; Howard and Rowlandson, 1981; Ferguson et al, 1981; Jaatoul et al, 1982; Jancar and Mlele, 1985]. A review suggests that this syndrome was described in three previous publications, the earliest dating back to 1944 [Ealing, 1944]. No minimal diagnostic criteria have been developed for this rare syndrome. A summary of the clinical findings of affected individuals is given in Table I. At present, no specific laboratory tests are useful in identifying these individuals. Chromosomes have been normal. Initially, it was thought that the primary defect was related to some type of myopathy [Passarge, 1975], but more recent findings suggest a central nervous system defect [Jaatoul et al, 1982]. Most of the reported cases are sporadic; however, pedigree studies have indicated apparent autosomal recessive inheritance, with five of 16 individuals having affected sibs [Howard and Rowlandson, 1981; Jaatoul et al, 1982] or cousins [Temtamy et al, 1975]. The long-term prognosis of individuals with this syndrome is unknown, although one individual was living at age 29 years [Jancar and Mlele, 1985].

TABLE I.

Summary of Manifestations in the Marden-Walker Syndrome

| Manifestations | Present case | Literature | Total | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Craniofacial | ||||

| Abnormal face | + | 16/16 | 17/17 | 100 |

| Blepharophimosis | + | 15/15 | 16/16 | 100 |

| Strabismus | + | 6/7 | 7/8 | 88 |

| Apparently low-set, abnormal ears | + | 11/13 | 12/14 | 86 |

| Micrognathia | + | 11/14 | 12/15 | 80 |

| Microcephaly | + | 7/12 | 8/13 | 62 |

| Hypertelorism | + | 3/8 | 4/9 | 44 |

| Cleft palate | − | 4/15 | 4/16 | 25 |

| Musculoskeletal | ||||

| Reduced muscle mass | + | 10/10 | 11/11 | 100 |

| Contractures at elbows knees, and hips | + | 14/15 | 15/16 | 94 |

| Kyphoscoliosis | + | 10/12 | 11/13 | 85 |

| Arachnodactyly | + | 7/9 | 8/10 | 80 |

| Camptodactyly | + | 5/8 | 6/9 | 67 |

| Talipes equinovarus | + | 6/10 | 7/11 | 64 |

| Pectus excavatum/carinatum | + | 6/10 | 7/11 | 64 |

| CNS function | ||||

| Psychomotor retardation | + | 14/14 | 15/15 | 100 |

| Hypotonia | + | 9/9 | 10/10 | 100 |

| Other | ||||

| Growth retardation | + | 14/15 | 15/16 | 94 |

| Simian crease | + | 6/10 | 7/11 | 64 |

| Cardiac anomalies | − | 6/11 | 6/12 | 50 |

| Family history | − | 5/16 | 5/17 | 29 |

| Renal abnormalities | − | 1/9 | 1/10 | 10 |

References

- Abe K, Niikawa N, Sasaki H. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome with Marden-Walker syndrome. Am J Dis Child. 1979;133:735–738. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1979.02130070071015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ealing MI. Amyoplasia congenita causing malpresentation of the foetus. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1944;15:144–146. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SD, Young ID, Teoh R. Congenital myopathy with oculofacial and skeletal abnormalities. Dev Med Neurol. 1981;23:232–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1981.tb02447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch N, Karpati G, Pinsky L. Congenital blepharophimosis, joint contractures and muscular hypotonia. Neurology. 1971;21:1214–1220. doi: 10.1212/wnl.21.12.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellis SS. Yearbook of Pediatrics. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers; 1963. p. 193. [Google Scholar]

- Howard FM, Rowlandson P. Two brothers with the Marden-Walker syndrome: Case report and review. J Med Genet. 1981;18:50–53. doi: 10.1136/jmg.18.1.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaatoul NY, Haddad NE, Khoury LA, Afifi AK, Bahuth NB, Deeb ME, Mikati MA, Kaloustian VM. Brief clinical report and review: The Marden-Walker syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1982;11:259–271. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320110303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jancar J, Mlele TJ. The Marden-Walker syndrome: A case report and review of the literature. J Mental Defic Res. 1985;29:63–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1985.tb00309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CR, Magenis E. The Marden-Walker syndrome. J Med Genet. 1978;15:366–369. doi: 10.1136/jmg.15.5.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marden PM, Walker WA. A new generalized connective tissue syndrome. Am J Dis Child. 1966;112:225–228. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1966.02090120093009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passarge E. Marden-Walker syndrome. Birth Defects. 1975;XI(2):470–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JL, Degnan M. A child with facial and skeletal dysmorphia reminiscent of Schwartz syndrome. Birth Defects. 1975;XI(2):456–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temtamy SA, Shoukry RA, Raafat M, Mihareb S. Probable Marden-Walker syndrome: Evidence for autosomal recessive inheritance. Birth Defects. 1975;XI(2):104–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younessian S, Ammann F. Deux cas de malformations craniofaciales. Opthalmologica. 1964;147:108–117. doi: 10.1159/000304574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]