Abstract

The nuclear import of histones is a prerequisite for the downstream deposition of histones to form chromatin. However, the coordinate regulation of these processes remains poorly understood. Here we demonstrate that Kap114p, the primary karyopherin/importin responsible for the nuclear import of histones H2A and H2B, modulates the deposition of histones H2A and H2B by the histone chaperone Nap1p. We show that a complex comprising Kap114p, histones H2A and H2B, and Nap1p is present in the nucleus and that the presence of this complex is specifically promoted by Nap1p. This places Kap114p in a position to modulate Nap1p function, and we demonstrate by the use of two different assay systems that Kap114p inhibits Nap1p-mediated chromatin assembly. The inhibition of H2A and H2B deposition by Kap114p results in the concomitant inhibition of RCC1 loading onto chromatin. Biochemical evidence suggests that the mechanism by which Kap114p modulates histone deposition primarily involves direct histone binding, while the interaction between Kap114p and Nap1p plays a secondary role. Furthermore, we found that the inhibition of histone deposition by Kap114p is partially reversed by RanGTP. Our results indicate a novel mechanism by which cells can regulate histone deposition and establish a coordinate link between histone nuclear import and chromatin assembly.

Chromatin assembly is a complex process which occurs in all eukaryotes and encompasses aspects of numerous cellular processes, including cell cycle progression, transcription, and DNA replication and repair (reviewed in reference 14). As with many other essential cellular processes, the chromatin assembly machinery is highly redundant (11, 14, 35). The numerous factors involved in this process can be broadly classified as histone transfer proteins (or chaperones) and ATP-dependent motor complexes (14, 35). These two classes of factors appear to be important for the initial deposition of histones onto DNA and for the formation of regularly spaced nucleosomes, respectively, as seen in vivo (14, 35). However, the mechanisms governing the spatial, temporal, and coordinate regulation of these factors remain unknown.

Thus far, the study of histone chaperones has revealed several evolutionarily conserved proteins which bind directly to histones and deliver them to chromatin. Almost all of these factors have a preference for either histones H3 and H4 or histones H2A and H2B (14). For example, CAF-1 and Asf1/RCAF have a strong preference for H3 and H4 (36, 37), while the histone chaperone Nap1 favors binding to H2A and H2B (5, 16, 25). These preferences may reflect the order in which histones are assembled into a nucleosome, which is believed to be initiated by the deposition of a tetramer of H3 and H4 onto DNA, followed by H2A-H2B dimer deposition (14). Specific chromatin assembly factors couple DNA replication and the assembly process, while other factors may function independently of DNA replication, for example, during transcription or DNA repair (11, 17). However, functional ties between the chromatin assembly machinery and the biogenesis of histones remain mostly unexplored. Soon after their synthesis, histones are modified by acetylation in the cytoplasm (33), but such a modification appears to be dispensable for chromatin assembly (22). The factors responsible for the ensuing nuclear import of core histones have recently been elucidated (24, 25), but how histone deposition is coordinated with the import process has not been studied.

The nuclear import of core histones, like virtually all other proteins bound for the nucleus, is mediated by the karyopherin/importin β (Kap) family of soluble transport factors (24, 25). Histone import relies on a network of karyopherins, which, like the histone chaperones, appear to have a preference for association with either H2A and H2B or H3 and H4 (24, 25). For example, in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the karyopherin Kap114p associates with H2A and H2B in vivo, while Kap123p is the predominant Kap associated with H3 and H4 (24, 25). Although intrinsic differences in structure may play a role in this specificity, other factors are likely involved in determining the histone preference of Kap proteins. We have recently demonstrated that the histone chaperone Nap1p plays a role in determining the Kap specificity for H2A and H2B (23). Nap1p functions in this manner by binding directly to Kap114p as well as to H2A and H2B, which results in an increased affinity of Kap114p for H2A and H2B (23). Conversely, the association of other Kaps with H2A and H2B is significantly inhibited in the presence of Nap1p (23). Thus, Nap1p serves not only as a histone chaperone but also as a cofactor involved in the nuclear transport of H2A and H2B.

Nap1p functions as a cofactor for Kap114p in a unique fashion. Associations of Kaps with their cofactors or cargoes are typically regulated by the small GTPase Ran, which is predominantly GTP bound in the nucleus and GDP bound in the cytoplasm (39). In the nucleus, the association of import Kaps with RanGTP results in the dissociation of cofactors or cargoes from the Kap proteins (39). In some cases, other factors have been shown to work in concert with RanGTP to stimulate dissociation (20, 28, 32). Interestingly, Nap1p remains bound to Kap114p even in the presence of high concentrations of RanGTP (23). This raises the possibility that Kap114p and Nap1p form a nuclear complex with histones, in which Kap114p may be able to modulate the histone chaperone function of Nap1p. In this study, we demonstrate that Kap114p interacts with Nap1p and histones in the nucleus and inhibits Nap1p-mediated histone deposition in vitro. This work suggests a novel link between the nuclear transport machinery and histone deposition and also implies that histone deposition may be spatially regulated within the nucleus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and plasmids.

The strains used for this study were derived from DF5 (9). Δnap1 derivatives were constructed by integration of the CloNATR marker into NAP1 (10). The Kap114-PrA, H2A-PrA, and H4-PrA strains have been described previously (24, 25, 28). Kap114-Myc derivatives were made by the integration of 13 Myc epitope repeats into the C terminus of KAP114 just upstream of the stop codon (using a cassette kindly provided by John Aitchison, Institute for Systems Biology). The Δkap114 strain was described previously (28).

Overexpression plasmids for full-length maltose binding protein (MBP)-tagged Kaps were previously described (23), while MBP-lacZα was overexpressed from the parental plasmid, pMAL-c2X (NEB). MBP-tagged Kap114p fragments were cloned and expressed in pMAL-c2X. Glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged Nap1p and its alanine substitution derivatives were expressed in pGEX-4T1 (Amersham). For the expression of Nap1p in yeast, the NAP1 open reading frame with 400 bp of upstream sequence was cloned into pRS314. Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged Nap1p derivatives were expressed by use of the pGFP2-C-FUS vector (25). Alanine substitution mutations in Nap1p were made by oligonucleotide site-directed mutagenesis and were verified by sequencing. pGEX-RCC1-GFP, pQE32-RanQ69L, and pQE32-RanT24N were kindly provided by Ian Macara (University of Virginia).

Cellular fractionation and immunoisolation.

Cytosol extracts were prepared from 1 liter of the indicated PrA-tagged strains (except for the experiment for Fig. 5C, in which 0.5 liter was used) as previously described (1). Nuclei were separated from cytosol extracts by centrifugation through a 0.3 M sucrose-8% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) cushion. After repeating this procedure, we resuspended the nuclear pellet by sonication into a solution containing 5 ml of 8% PVP, 18.5 ml of 1× TB-20 (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 110 mM potassium acetate, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Tween 20), and protease inhibitors. The nuclei were further lysed by use of a French press, resulting in a total nuclear extract, which was analyzed for purity by the use of antibodies against Pgk1p (Molecular Probes) and acetylated histone H4 (Upstate). For immunoisolation, the total nuclear extract was clarified by centrifugation, and PrA-tagged proteins were isolated from the resulting supernatant by the use of immunoglobulin G (IgG)-Sepharose as previously described (1, 27). The analyzed unbound fractions represent 0.08% (for Kap114-PrA) or 0.04% (for histone-PrA) of the total unbound material. Proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-Nap1p antibody (Santa Cruz) and an anti-Myc antibody (Sigma).

FIG. 5.

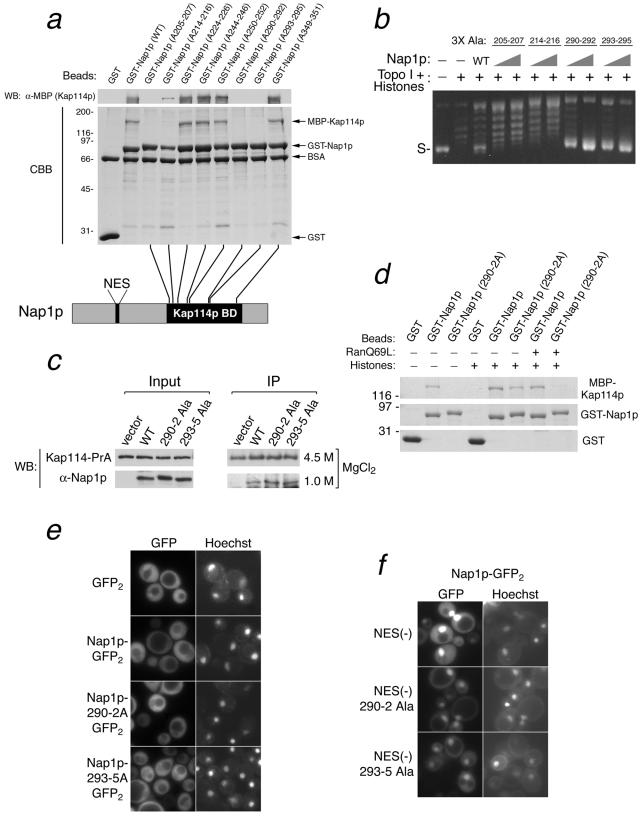

Characterization of Nap1p point mutants. (a) Alanine mutations of Nap1p abolish its Kap114p binding. Binding assays were performed on glutathione-Sepharose with 2 μM GST or a 400 nM concentration of each GST-Nap1p mutant in the presence of 300 nM MBP-Kap114p. Eighty percent of the bound material was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue (CBB) staining. The remaining material was analyzed by Western blotting (WB) with an anti-MBP antibody. The schematic shows the relative positions of alanine mutations in the Kap114p-binding domain (BD)of Nap1p. (b) Plasmid supercoiling assays were performed with 500 nM wild-type Nap1p or 250 and 500 nM concentrations of the indicated Nap1p mutants. (c) A Kap114-PrA-expressing Δnap1 strain was constructed and transformed with vector alone or with a plasmid expressing wild-type Nap1p or the indicated Nap1p mutant. The cytosol was prepared from each strain and analyzed for the expression of Nap1p and Kap114-PrA by Western blotting (input). The same cytosol was used for immunoisolation of Kap114-PrA and associated proteins (IP). After being washed, the associated proteins were eluted with a buffer containing the indicated concentrations of MgCl2 and then analyzed by Western blotting for Nap1p and Kap114-PrA. (d) Binding between MBP-Kap114p and the indicated GST proteins was analyzed as described for panel a in the presence or absence of core histones (500 nM) and RanQ69L (20 μM), as indicated. (e and f) The localization of the indicated GFP-tagged proteins was analyzed in wild-type yeast. Coincident Hoechst staining is also shown.

Purification of recombinant proteins and in vitro binding assays.

MBP-lacZα and MBP-tagged Kaps were purified as previously described (23). GST, GST-H2A1-46, GST-Nap1p, tag-free Nap1p, and its mutant derivatives were purified as previously described (23). Recombinant RCC1-GFP was expressed as a GST fusion in Escherichia coli BL21 cells and was purified by the use of glutathione-Sepharose (Amersham), and the GST tag was then removed with thrombin (Sigma). His6-tagged RanQ69L and T24N were purified on Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose (QIAGEN). Upon purification, all recombinant proteins were dialyzed against 1× TB-20-15% glycerol. In vitro binding assays were performed as previously described (23).

Plasmid supercoiling assays.

Purified, supercoiled pBluescript DNA (250 ng) was relaxed by incubation with 1 U of topoisomerase I (Promega) at 37°C for 1 h in a solution containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.1 mM EDTA (topoisomerase buffer) in a volume of 10 μl. In a separate reaction, chicken erythrocyte core histones (500 ng) were added to Nap1p and the MBP-tagged protein (when indicated) and then incubated at 22°C for 30 min in topoisomerase buffer. EDTA was added to the histone-Nap1p reactions to a final concentration of 20 mM, and the reactions were incubated for another 10 min at 22°C. The topoisomerase and histone reactions were then combined (total volume of 40 μl) and incubated at 22°C for 1 h for histone deposition. The reactions were stopped and deproteinized by the addition of proteinase K (20 μg) and 0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). After phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation, DNAs were separated by electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide to assess supercoiling.

Xenopus laevis sperm chromatin assembly and microscopy.

Demembranated sperm chromatin (5 × 105 per reaction; kindly provided by Ian Macara, University of Virginia) decondensation was performed with recombinant Nap1p (1 μM) at 22°C for 15 min in 1× TB-20-15% glycerol in a total volume of 10 μl per reaction. Separately, chicken erythrocyte core histones (500 ng/reaction) were incubated with the indicated concentration of MBP-tagged protein or with buffer (1× TB-20-15% glycerol) in a total volume of 10 μl and then kept on ice. Tetramethyl rhodamine isocyanate (TRITC)-labeled H2A and H2B were prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions (Molecular Probes). TRITC-labeled H2A and H2B and recombinant RCC1-GFP (200 nM) were added to the histone cocktail when indicated. For reaction mixtures containing Ran, the indicated Ran mutant was preincubated with MBP-Kap for 30 min at 4°C prior to the addition of core histones. The decondensation reaction mix was combined with the histone cocktail and incubated for 15 min at 22°C. Reactions intended for visual analyses of histone deposition were stained with Hoechst 33342, fixed, and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. Fluorescence microscopy images were acquired with a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope and manipulated with Openlab 3.1.4 imaging software. The fluorescent images shown were acquired with identical exposure settings and were manipulated identically in Adobe Photoshop. Chromatin assembly reactions intended for Western blot analysis were spun through a 0.5-ml 30% sucrose cushion at 4,000 × g for 1 h. The chromatin pellets were resuspended in SDS sample buffer, boiled, analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and Western blotted with an anti-H2B antibody (Upstate).

RESULTS

Association of Nap1p and Kap114p with histones in the nucleus.

Previously, we demonstrated that Kap114p specifically binds to Nap1p and forms a multimeric complex containing Nap1p and histones in the cytosol (23). Although the association between Kap114p and H2A/H2B is inhibited in the presence of RanGTP, the complex containing Nap1p is insensitive to RanGTP (23). We therefore surmised that the association between Kap114p and Nap1p may persist in the nucleus. To test this, we prepared a nuclear extract from a Kap114-PrA-expressing yeast strain. Immunoisolation of Kap114-PrA from this extract was performed, and the associated proteins were eluted with a MgCl2 step gradient (Fig. 1a). Western blotting confirmed the presence of Nap1p associated with Kap114p in this nuclear extract. As a control for our fractionation method, we compared the levels of a cytoplasmic enzyme, Pgk1p, and histone levels in cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts prepared from Kap114-PrA-expressing cells. This demonstrated that our fractionation technique was successful in yielding cytosolic and nuclear extracts (Fig. 1b).

FIG. 1.

Kap114p associates with Nap1p and histones in the nucleus. (a) Kap114-PrA nuclear extract was incubated with IgG-Sepharose and then washed, and proteins were eluted with a MgCl2 step gradient and then analyzed by Western blotting (WB) with an anti-Nap1p antibody. Molecular standards, in kilodaltons, are indicated on the left. (b) Equivalent amounts of cytosol and nuclear extracts from Kap114-PrA cells were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against Pgk1p or acetylated H4. H2A-PrA (c) and H4-PrA (d) and associated proteins were isolated from nuclear extracts and analyzed by Coomassie staining (CBB) or Western blotted with the indicated antibodies. The fractions shown in panels c and d were analyzed on the same gel and blot and were treated identically. Wash, final wash fraction; U/B, unbound fraction. (e) H2A-PrA and associated proteins were isolated from nuclear extracts as described for panel c, washed, incubated with 20 μM RanQ69L at room temperature for 1 h, washed again, eluted, and analyzed as described above. Wash-1, final wash fraction prior to RanQ69L addition; Wash-2, wash fraction prior to MgCl2 elution. (f) Binding of MBP-Kap114p (250 nM) to GST-H2A1-46 (1 μM) was assessed in the presence or absence of Nap1p (1 μM) and/or RanQ69L (20 μM).

In order to determine whether nuclear Nap1p and Kap114p were associated with histones, we used the protocol described above to prepare a nuclear extract from H2A-PrA/Kap114-Myc-expressing cells. Immunoisolation of H2A-PrA and associated proteins demonstrated that both Nap1p and Kap114p were indeed associated with H2A-PrA in the nucleus (Fig. 1c). As a control, in a parallel experiment using a nuclear extract from H4-PrA- and Kap114-Myc-expressing cells, we found very little Nap1p or Kap114p associated with this histone (Fig. 1d). Thus, within the nucleus, Kap114p is bound to Nap1p and histones as it is in the cytosol.

Although it was unlikely, it was possible that during the preparation of the nuclear extract, the nuclear milieu was disrupted, causing a loss of RanGTP and resulting in the reassociation of Kap114p with Nap1p and histones. To address this issue, we performed the immunoisolation assay with an H2A-PrA/Kap114-Myc nuclear extract. After being washed, the beads were incubated with 20 μM RanQ69L (a constitutively GTP-bound form of Ran) (31). The Ran-containing fraction was eluted, the beads were washed a second time, and any associated proteins were eluted from the beads as before. An analysis of these fractions demonstrated that while a small amount of Kap114p was eluted with the RanGTP, most of the Kap114p (and Nap1p) remained bound to the H2A-PrA (Fig. 1e). At an equivalent concentration of RanGTP, direct binding between recombinant Kap114p and the H2A nuclear localization signal (NLS) was disrupted, demonstrating that the recombinant RanGTP was active (Fig. 1f). In addition, consistent with our previous observations, after the addition of Nap1p, the Kap114p interaction with H2A became insensitive to RanGTP (Fig. 1f) (23). Taken together, these results suggest that the observed stability of the nuclear H2A-PrA-Kap114p complex may be due to the presence of Nap1p in this complex.

The nuclear Kap114p-histone complex persists in the nucleus primarily because of Nap1p.

To test the hypothesis that Nap1p contributes to the stability of the Kap114p-histone complex in the nucleus, we created an H2A-PrA/Kap114-Myc-expressing Δnap1 strain. In parallel, a nuclear extract was prepared from this strain as well as from the H2A-PrA/Kap114-Myc strain. H2A-PrA and associated proteins were isolated from this extract and analyzed as described above. We found that, as expected, the band corresponding to Nap1p was absent from the Δnap1 strain, while most other H2A-associated proteins appeared to be present in relatively equal amounts (Fig. 2). Interestingly, the amount of Kap114-Myc associated with H2A-PrA was significantly reduced in the Δnap1 strain. This suggested that in the presence of Nap1p, the Kap114p-histone complex can persist in the nucleus, even in the nuclear milieu with predicted high levels of RanGTP.

FIG. 2.

Nap1p promotes the association of Kap114p with histones in the nucleus. H2A-PrA and associated proteins were isolated from nuclear extracts from the indicated strains with IgG-Sepharose. Fractions were eluted with a MgCl2 step gradient and analyzed by Coomassie staining (CBB) or Western blotted (WB) and probed with an anti-Myc antibody.

Kap114p inhibits histone deposition by Nap1p in vitro.

The nuclear association of Kap114p with Nap1p and histones led us to postulate that Kap114p may play a role in modulating Nap1p-mediated histone deposition. We initially tested this by using a plasmid-based, replication-independent chromatin assembly assay (19). Nap1p was capable of assembling chromatin onto this template, as indicated by increased supercoiling of the plasmid in the presence of histones and topoisomerase I (Fig. 3a). Surprisingly, the addition of recombinant MBP-Kap114p was able to inhibit Nap1p-mediated chromatin assembly in a concentration-dependent fashion (Fig. 3a). In contrast, no inhibition was observed with the addition of a control MBP fusion protein (MBP-lacZα) (Fig. 3a).

FIG. 3.

Kap114p inhibits Nap1p-mediated chromatin assembly on plasmid templates. (a) Plasmid supercoiling assays were performed according to the schematic by the use of recombinant Nap1p (500 nM) in the presence of MBP-Kap114p or MBP-lacZα (625 nM, 1.25 μM, or 2.5 μM), as indicated. After deproteinization, the DNAs were analyzed in an agarose gel. (b) Reactions were performed with Nap1p according to the schematic, incubated with MBP-Kap114p or MBP-lacZα (625 nM, 1.25 μM, or 2.5 μM) for 1 h, and analyzed as described above. S, supercoiled DNA.

We wished to eliminate the possibility that Kap114p was not inhibiting chromatin assembly in these reactions but was somehow modulating the chromatin structure or disassembling the chromatin after its assembly by Nap1p. To test this, we performed Nap1p-mediated chromatin assembly as described above, using plasmid DNA as a template. After assembly, the reactions were incubated with the same concentrations of MBP-Kap114p or MBP-lacZα. As shown in Fig. 3b, Kap114p was not capable of altering the supercoiling of the plasmid when it was added after assembly. Thus, Kap114p acts during an early step in chromatin assembly, most likely by a direct interaction with Nap1p or the histones themselves.

Kap114p inhibits H2A and H2B deposition onto Xenopus sperm chromatin.

While Nap1p is apparently capable of depositing the full octamer of histones in vitro, it is likely that in vivo the function of Nap1p is primarily to serve as a deposition factor for H2A and H2B due to its preference for these histones (5, 16, 25). To reflect this, we developed a novel visual assay using Xenopus sperm chromatin, which lacks histones H2A and H2B but contains H3 and H4 (29), as a template for chromatin assembly. Prior to H2A and H2B deposition, sperm-specific protamines must be removed, which is normally performed by nucleoplasmin present in the Xenopus egg (30). Removal of the protamines is signified visually by decondensation of the sperm chromatin (30). Nap1p was capable of replacing nucleoplasmin in the decondensation reaction (Fig. 4a) (18), leaving a template suitable for analyzing H2A and H2B deposition. The addition of TRITC-labeled H2A and H2B to the reaction allowed direct visualization of histone deposition onto the sperm chromatin. As expected, no TRITC signal was detected on the Nap1p-decondensed sperm without the addition of the labeled histones (Fig. 4b). In the absence of Nap1p, relatively little H2A and H2B deposition onto the sperm chromatin was observed (Fig. 4b). The presence of Nap1p resulted in a significant increase in the amount of deposited fluorescent H2A and H2B (Fig. 4b). The addition of excess unlabeled histones effectively competed with the loading of labeled H2A and H2B, demonstrating that the deposition of the labeled histones occurs in a saturable and specific fashion (Fig. 4b). The loading of RCC1-GFP onto chromatin, which requires the prior deposition of H2A and H2B (26), was also used to confirm the loading of these histones onto the chromatin (see below), supporting the notion that this assay was well suited for studying the deposition of H2A and H2B.

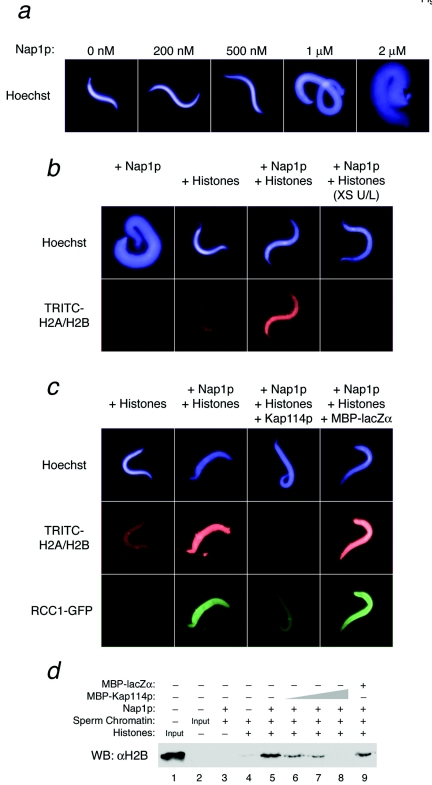

FIG. 4.

Kap114p inhibits histone H2A and H2B deposition onto Xenopus sperm chromatin. (a) Nap1p decondenses Xenopus sperm chromatin. Sperm chromatin was incubated with the indicated concentrations of Nap1p, fixed, stained with Hoechst, and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. (b) Sperm chromatin was decondensed with 1 μM Nap1p as indicated. Reactions were then incubated with core histones and TRITC-labeled H2A and H2B as indicated. Excess unlabeled (XS U/L) core histones (5 μg) were added to the reaction on the right. The reactions were fixed and stained with Hoechst. (c) Reactions were performed as described above in the presence of RCC1-GFP (200 nM) and MBP-Kap114p or MBP-lacZα (1 μM each), as indicated. (d) Reactions were performed as described above, using only unlabeled histones in the presence of MBP-Kap114p (200 nM, 500 nM, or 1 μM) or MBP-lacZα (1 μM), as indicated. The chromatin was isolated and analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-H2B antibody.

To study the effect of Kap114p on H2A and H2B deposition by using this system, we added MBP-Kap114p to the reaction simultaneously with the histones. The addition of 1 μM MBP-Kap114p significantly inhibited H2A and H2B loading onto the sperm chromatin, while the same concentration of MBP-lacZα had no effect (Fig. 4c). Since the loading of RCC1 has been previously shown to require H2A and H2B deposition (26), we simultaneously analyzed the loading of RCC1-GFP in the same reactions. We confirmed that RCC1-GFP is only loaded onto the sperm chromatin in the presence of both Nap1p and histones (Fig. 4c). Furthermore, the specific loading of RCC1-GFP was inhibited by MBP-Kap114p but not by MBP-lacZα (Fig. 4c).

To confirm our results using nonfluorescently labeled histones, we also performed a parallel experiment in which the deposition of unlabeled histones was analyzed by Western blotting. After the assembly reaction, the sperm chromatin was separated by centrifugation through a 30% sucrose cushion, and histone H2B deposition was analyzed by blotting with a specific antibody. In agreement with the above experiments, H2B was deposited onto the chromatin in the presence of Nap1p (Fig. 4d, cf. lanes 4 and 5). We found that the addition of increasing concentrations of Kap114p to these reactions resulted in a decrease in the amount of H2B loaded onto the chromatin (Fig. 4d, cf. lanes 5 to 8). Again, the concentration-dependent inhibition of histone deposition by Kap114p was evident, confirming the results observed in the fluorescence-based assay as well as the plasmid supercoiling assay. Taken together, these results suggest for the first time that Kap114p can inhibit Nap1p function.

Mutants of Nap1p deficient in Kap114p binding can still be recruited to the Kap114p-histone complex via interaction with the histone.

We next set out to determine the mechanism by which Kap114p inhibits histone deposition by Nap1p. It was possible that Kap114p modulated histone deposition either through its direct interaction with Nap1p or via a direct interaction with the histones themselves. To distinguish between these two possibilities, we engineered alanine substitution mutants of Nap1p which could no longer interact with Kap114p but retained their function as histone chaperones (Fig. 5a). Eight triple alanine substitution mutants were created in the Kap114p binding domain of Nap1p (Fig. 5a) (23). GST-Nap1p fusion proteins were purified and tested for the ability to interact with MBP-Kap114p. Four of these mutants exhibited significantly reduced or undetectable binding to MBP-Kap114p (Fig. 5a). These four mutants were then tested for histone chaperone activity after purification and removal of the GST moiety. We found that two of these mutants, Nap1p(290-292 3X Ala) and Nap1p(293-295 3X Ala), retained the ability to deposit histones, as determined by the plasmid DNA supercoiling assay (Fig. 5b).

To characterize the interaction between these two Nap1p mutants and Kap114p in vivo, we expressed them in a Kap114-PrA-expressing Δnap1 strain (Fig. 5c). A cytosol extract was prepared from each strain, and Kap114-PrA and associated proteins were isolated and analyzed as described earlier. Surprisingly, we found that these two Nap1p mutants interacted with Kap114p in vivo (Fig. 5c). It was possible that in vivo the presence of histones H2A and H2B could bridge the interaction between Kap114p and Nap1p, as suggested by our previously published work (23). To test this possibility, we performed an in vitro binding assay using immobilized Nap1p or the Nap1(290-292 3X Ala) mutant and Kap114p in the presence or absence of histones. We found that the mutant Nap1 protein could only recruit Kap114p in the presence of histones, suggesting an indirect interaction (Fig. 5d). If Nap1p interacted with Kap114p via histones, we would expect this complex to be sensitive to RanGTP. Accordingly, we showed that the addition of RanGTP to the complex resulted in a loss of Kap114p binding (Fig. 5d).

The above data suggested that even in the absence of a direct interaction with Kap114p, the Nap1p mutants could indirectly interact with Kap114p (or other Kaps) via histones H2A and H2B. To test this in vivo, we expressed these proteins as fusions to GFP (Fig. 5e). We found that the localization of the two Nap1p mutants was very similar to that of wild-type Nap1p, with predominant cytoplasmic localization and some nuclear exclusion (Fig. 5e). We previously demonstrated the presence of a nuclear export signal (NES) near the N terminus of Nap1p (23). Mutation of the four leucines in this NES to alanine conferred nuclear accumulation of the Nap1p-GFP reporter (Fig. 5f). The same nuclear localization was seen when the NES sequences of two Nap1p mutants were eliminated (Fig. 5f). Thus, these Nap1p mutants can be imported into the nucleus in vivo.

Direct interaction between Kap114p and Nap1p contributes to but is not required for inhibition of histone deposition.

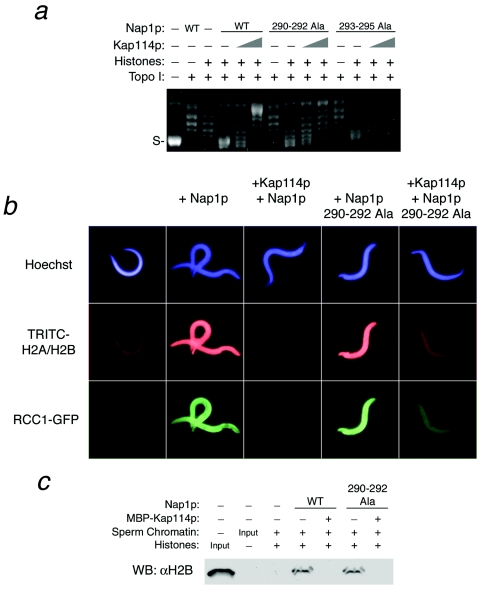

We then compared the ability of Kap114p to inhibit the histone chaperone activity of wild-type Nap1p versus the two Nap1p mutants. Kap114p was still capable of inhibiting chromatin assembly by both mutants, suggesting that the interaction between Kap114p and Nap1p is not necessary for this activity (Fig. 6a). Nevertheless, the observed inhibition of wild-type Nap1p was more pronounced than the inhibition of either Nap1p mutant. These results suggested that the interaction of Kap114p with Nap1p may play a role in its inhibitory activity, although it is not absolutely required.

FIG. 6.

Direct interaction between Nap1p and Kap114p contributes to but is not essential for inhibition of histone deposition. (a) Supercoiling assays were performed with wild-type Nap1p or the indicated Nap1p mutants (500 nM) in the presence of MBP-Kap114p (1 or 2.5 μM) as indicated. Histone deposition assays were performed on Xenopus sperm chromatin and were visualized by microscopy (b) or Western blotting (WB) (c) with 1 μM wild-type Nap1p or Nap1p(290-292 Ala). The concentration of MBP-Kap114p was 1 μM for panel b and 500 nM for panel c.

We next tested the Nap1p mutants by using a Xenopus sperm chromatin assay. The Nap1p(290-292 3X Ala) mutant was capable of facilitating H2A and H2B deposition onto sperm chromatin, as determined by the incorporation of fluorescent histones (Fig. 6b). With this mutant, we observed a marked inhibition of histone and RCC1-GFP deposition in the presence of Kap114p (Fig. 6b). We also determined the amount of unlabeled H2B deposited on the sperm chromatin by Western blot analysis in a separate experiment. This confirmed that Kap114p inhibited histone deposition onto chromatin by the Nap1p mutant (Fig. 6b). We obtained similar data for the other Nap1p mutant [Nap1p(293-295 3X Ala)] with these assays (data not shown). These results are consistent with the experiments performed with plasmid templates and suggest that Nap1p binding by Kap114p is not an absolute requirement for the inhibition of histone deposition.

Kap114p contains multiple histone-binding domains that are required for the inhibition of histone deposition.

From the above results, it was likely that the primary mechanism used by Kap114p to inhibit Nap1p-mediated histone deposition was through its direct interaction with histones. To test this, we first needed to map the domain(s) within Kap114p that is responsible for histone binding. We cloned and purified several fragments of Kap114p as MBP fusions. These fragments were then tested for the ability to bind to the histone H2A NLS (residues 1 to 46). Unexpectedly, we determined that three nonoverlapping domains of Kap114p are capable of direct interactions with this histone (Fig. 7). Full-length Kap114p bound to H2A, as did fusions comprising amino acids 1 to 897 and 1 to 566, whereas amino acids 1 to 240 did not appear to confer H2A binding (Fig. 7b). To further investigate the domain between amino acids 240 and 566, we showed that while this entire domain bound H2A, the binding site appeared to be in the N-terminal half of this fragment, as the region of amino acids 240 to 400 interacted, whereas amino acids 400 to 566 did not confer binding to H2A (Fig. 7c). A nonoverlapping fragment consisting of the C-terminal half of Kap114p (positions 566 to 1004) suggested that there must be additional histone-binding domains within this half of the protein (Fig. 7d). Since a fragment consisting of amino acids 680 to 1004 interacted strongly with H2A, whereas the region of amino acids 680 to 897 did not mediate an interaction, we deduced that an additional histone-binding domain was contained between amino acids 897 and 1004 (Fig. 7d). Surprisingly, we also determined that while fragments containing both amino acids 400 to 680 and 566 to 1004 conferred binding, the regions of amino acids 400 to 566 and 680 to 897 did not interact with H2A, suggesting that an additional histone-binding site is located between amino acids 566 and 680. Thus, a total of three nonoverlapping histone-binding domains appear to exist within Kap114p (Fig. 7e).

FIG. 7.

Kap114p contains multiple histone-binding domains. (a) The indicated MBP-tagged Kap114p deletions were expressed and purified from bacteria. Twenty picomoles of each (100% of the input for subsequent binding studies) was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. (b to d) Binding between each MBP-Kap114p deletion (200 nM) and GST (2 μM) or GST-H2A1-46 (1 μM) was tested and analyzed as shown. (e) Schematic showing the histone-binding domains of Kap114p as determined by the deletion analysis shown in panels b to d. Solid gray lines represent fragments which lacked binding.

We then tested whether any particular histone-binding domain(s) was responsible for the inhibition of histone deposition by Nap1p. As expected, residues 1 to 240, which do not contain a histone-binding domain, were neither necessary nor sufficient for the inhibition of histone deposition (Fig. 8a and b). We found that the deletion of the most C-terminal histone-binding domain of Kap114p (amino acids 897 to 1004) resulted in a significant loss in the ability of Kap114p to inhibit histone deposition (Fig. 8c). However, a fragment of Kap114p containing only this histone-binding domain (amino acids 680 to 1004) was not fully functional in the inhibition of chromatin assembly, although it did show some activity compared to amino acids 1 to 897 (Fig. 8c). This suggested that more than one histone-binding domain is necessary for inhibition, and accordingly a fragment containing the C-terminal half of Kap114p (residues 566 to 1004) containing both binding domains (amino acids 566 to 680 and 897 to 1004) was capable of inhibiting chromatin assembly, whereas the N-terminal half, containing the domain of amino acids 240 to 400, was not (Fig. 8d). Thus, it appears that Kap114p contains multiple histone-binding domains and that the inhibition of chromatin assembly rests primarily with the two C-terminal histone-binding motifs.

FIG. 8.

Multiple histone-binding domains contribute to the modulation of histone deposition by Kap114p. (a) Portion of schematic from Fig. 7e depicting Kap114p histone-binding domains (hatched areas). (b to d) Supercoiling assays were performed as described in the text by the use of 500 nM Nap1p in the presence of the indicated MBP-tagged fragments of Kap114p (1 μM).

Other histone-binding karyopherins can inhibit Nap1p-mediated histone deposition.

Although Kap114p is the primary karyopherin associated with H2A and H2B, other karyopherins, such as Kap121p and Kap123p, can also bind to these histones and serve as secondary import factors (25). If histone binding is the primary mechanism for the observed inhibition of histone deposition, then we would predict that Kap121p and Kap123p should also be able to inhibit histone deposition by Nap1p, at least to some degree. We tested whether MBP-tagged Kap121p and Kap123p could replace Kap114p's ability to inhibit chromatin assembly. Using the supercoiling assay, we found that both of these Kaps inhibited histone deposition (Fig. 9a). However, Kap121p was somewhat weaker than Kap114p in its inhibitory activity, while Kap123p was clearly weaker still, with only a marginal degree of inhibition observed at the highest concentration tested (Fig. 9a). Using sperm chromatin as the template for histone deposition, we found that both Kaps can inhibit fluorescent histone deposition, although to a slightly lesser degree than Kap114p (Fig. 9b). An analysis of histone deposition onto sperm chromatin by Western blotting confirmed that these two Kaps did indeed inhibit histone H2B loading (Fig. 9c). These experiments support the notion that these Kaps can inhibit histone deposition in vitro, likely by direct interactions with histones H2A and H2B. However, since Kap114p preferentially binds H2A and H2B and can also interact with Nap1p, it is likely the predominant Kap that can regulate histone deposition by Nap1p in vivo (23).

FIG. 9.

Other histone-binding karyopherins can inhibit histone deposition in vitro. (a) Plasmid supercoiling assays were performed with 500 nM Nap1p and a 500 nM, 1 μM, or 2.5 μM concentration of the indicated MBP-Kaps. Histone deposition assays were performed on Xenopus sperm chromatin and were visualized by microscopy (b) or Western blotting (WB) (c) as described in the text by the use of 1 μM Nap1p and a 1 μM concentration (b) or 200 and 500 nM concentrations (c) of the indicated Kaps.

Partial modulation of Kap114p-mediated inhibition of histone deposition by RanGTP.

Since histone binding appeared to be the primary determinant of Kap-mediated inhibition of histone deposition, we were prompted to test whether RanGTP could reverse this inhibition. We initially tested this by using the plasmid supercoiling assay. For Kap114p and Kap121p, we found that the addition of 20 μM RanQ69L (a constitutively GTP-bound Ran mutant) (31) caused a reversal of the chromatin assembly inhibition, albeit to different degrees for each Kap (Fig. 10a and b). RanGTP appeared to have a stronger effect on Kap121p, with which the amount of supercoiled template returned to the levels seen in the absence of Kap addition (Fig. 10a and b). This result suggested that RanGTP modulates the Kap-mediated inhibition of histone deposition. Using the sperm chromatin assay, we observed similar results when monitoring the amount of histone H2B deposited onto the sperm chromatin by Western blotting (Fig. 10c, cf. lanes 6 to 8 with lanes 9 to 11 and lanes 12 to 14 with lanes 15 to 17). Again, a stronger effect of RanQ69L on Kap121p inhibition versus Kap114p inhibition was evident (cf. lanes 9 to 11 and lanes 15 to 17 in Fig. 10c). To test whether the nucleotide state of Ran was critical for this modulation, we compared the effect of RanQ69L with that of RanT24N, a dominant-negative form of Ran that binds nucleotides poorly and hence would not be expected to interact with Kaps (7, 21). In contrast to RanQ69L, RanT24N was unable to reverse the Kap114p-mediated histone deposition inhibition, implying that the GTP-bound form of Ran is required for this activity (data not shown). These data suggest that RanGTP may play a role in regulating the inhibitory effect of Kaps on histone deposition.

FIG. 10.

RanGTP can reverse the Kap114p-mediated inhibition of histone deposition. (a and b) Plasmid supercoiling assays were performed with 500 nM Nap1p, 1 and 2 μM MBP-Kap114p or MBP-Kap121p, and 20 μM RanQ69L as indicated. (c) Histone deposition assays were performed on sperm chromatin with 1 μM Nap1p, the indicated Kap (200 nM, 500 nM, or 1 μM), and 20 μM RanQ69L analyzed by Western blotting as shown.

Taken together, our results suggest that Kap114p negatively regulates histone deposition mediated by Nap1p. Direct histone binding appears to be the primary mechanism by which this modulation is achieved. Our data suggest that RanGTP may be capable of modulating this inhibitory activity.

DISCUSSION

We have previously shown that Nap1p enters the nucleus in a complex with Kap114p, H2A, and H2B and functions as a cofactor for histone import mediated by Kap114p (23). Several Kaps can bind and import H2A and H2B, but only Kap114p binds Nap1p. Nap1p competes with other Kaps for the histones and directs H2A and H2B specifically to Kap114p (23). We have also shown that Nap1p renders the Kap114p-histone complex insensitive to RanGTP (23). This is consistent with our present findings that Kap114p remains associated with Nap1p, H2A, and H2B in the nucleus and that the presence of Nap1p specifically promotes this nuclear complex. For this report, we used two independent assays for chromatin assembly, namely, a DNA supercoiling assay and the Xenopus sperm chromatin system. We have established the following three criteria for assessing the incorporation of histones into sperm chromatin: visualization of fluorescently labeled histones, Western blotting for H2B, and an interaction of RCC1 with the chromatin template. Surprisingly, all of these assays demonstrated that Kap114p inhibits the Nap1p-mediated incorporation of H2A and H2B into chromatin. This raised the possibility that Kap114p may be able to regulate chromatin assembly. Investigations into the mechanism of Kap114p-mediated histone deposition suggested that histone binding is the primary determinant of this activity.

Kap114p contains three nonoverlapping histone-binding domains. Without structural data, it is not known whether these domains fold around and make multiple contacts on a single histone or whether more than one histone can be contacted at one time. It appeared that at least two of these histone-binding domains contribute to the ability of Kap114p to inhibit chromatin assembly. Two other histone-binding Kaps, Kap121p and Kap123p, could also inhibit histone deposition in vitro. However, they were less effective than Kap114p, possibly because they bind the histones with lower affinities or are partially outcompeted by Nap1p. We do not know the relevance of the inhibitory activity of these Kaps in vivo, as H2A and H2B preferentially interact with Kap114p (25). In addition, unlike Kap114p, these Kaps may not form a nuclear complex with H2A and H2B, as their interaction is sensitive to RanGTP (23, 25). Consistent with this, RanGTP was more effective at reversing the inhibition observed with Kap121p than that observed with Kap114p.

We previously demonstrated that Kap114p can directly bind to both Nap1p and histones in a noncompetitive fashion (25). Furthermore, we demonstrated that Kap114p can bind to histones indirectly with Nap1p serving as a bridging factor, forming a RanGTP-insensitive complex (25). Here we demonstrated that Kap114p can be recruited to Nap1p indirectly via binding histones, forming a RanGTP-sensitive complex. Thus, Nap1p may be able to interact with the nuclear transport machinery both directly and indirectly. This was supported by experiments which showed that two mutant Nap1p proteins which cannot interact directly with Kap114p can still gain access to the nucleus. These data also suggest that the Kap114p-Nap1p-histone complex is rather flexible and has at least two conformations depending on the presence of RanGTP. In the absence of RanGTP, Kap114p makes contact with both Nap1p and histones, and nucleosome assembly is inhibited. When bound to RanGTP, the Kap114p-histone association is likely eliminated, but Kap114p stays bound to the complex via Nap1p. However, in this configuration, the complex may be poised for chromatin assembly. Further studies are needed to determine how the Kap114p-Nap1p complex is finally disassembled.

Most chromatin assembly factors are not essential, suggesting that this process can be performed by many functionally overlapping factors. Since histone binding appears to be critical for Kap114p's inhibitory effect, it is possible that the functions of other assembly factors are regulated by Kap114p. Nap1p is not essential, and other assembly factors must be able to act as H2A and H2B chaperones in vivo. However, in vivo this inhibition may be specific to Nap1p; in the absence of Nap1p, the affinity of Kap114p for histones would be reduced, and as we have shown, significantly less Kap114p-histone complex persists in the nucleus. Under these conditions, it is possible that Kap114p no longer inhibits chromatin assembly.

Kap114p can inhibit the deposition of histones onto DNA, and we predict that this must be a transient and reversible event. RanGTP is known to stimulate the release of cargoes from import Kaps, and in the presence of Kap114p and RanGTP, we were able to observe Nap1p-mediated histone deposition. However, a complete reversal of inhibition to levels observed in the absence of Kap114p was not seen. Similar concentrations of RanGTP efficiently reversed the inhibitory effect of Kap121p. It is possible that another factor(s) is required, in addition to RanGTP, to allow histone deposition to take place and dissociate the Kap114p-Nap1p-histone complex. A precedent for this has been observed in which the RanGTP-mediated release of TATA-binding protein from Kap114p was stimulated by TATA-containing DNA (28). Alternatively, Kap114p may require a higher concentration of RanGTP to reverse the inhibition, possibly because Kap114p binds histones with a higher affinity due to the presence of Nap1p in the complex or because Kap114p may have a lower affinity for RanGTP than that of Kap121p. This raises the possibility that the dissociation of Kap114p from the histones only occurs in areas of the nucleus with sufficiently high concentrations of RanGTP. The exchange factor for Ran, RCC1 (Prp20p in yeast), generates RanGTP (39). RCC1 is concentrated at the surface of chromatin through interactions with H2A and H2B, suggesting that the highest concentrations of RanGTP will be found in the vicinity of RCC1 at the chromatin surface (26). Interestingly, we observed that RCC1 loading onto chromatin was also inhibited by Kap114p, most likely due to the inhibition of H2A and H2B loading, as RCC1 and H2A-H2B loading are intimately tied to one another (26). Further work is needed to assess whether Kap114p can coordinately regulate RCC1 and H2A-H2B loading at specific sites within the genome.

We showed here that the nuclear function of Nap1p may be regulated in a negative and a positive fashion by karyopherins and RanGTP, respectively. Similarly, karyopherins and RanGTP have been shown to act in a negative and a positive fashion in other nuclear functions. Examples include the assembly of the mitotic spindle (6) as well as nuclear envelope and nuclear pore complex assembly (13, 15, 38). In higher eukaryotes, the nuclear envelope breaks down at mitosis, and RanGTP, found in high concentrations at the chromatin surface, acts as a marker for the nucleus and is the site of dissociation of cargoes that are necessary for the formation of the spindle and for envelope assembly. For yeast, although there is a closed mitosis, we predict that RanGTP is not uniformly distributed throughout the nucleus but is found concentrated in various domains at the surface of chromatin as discussed above. Interestingly, a recent study has suggested that Prp20p is not evenly distributed throughout the yeast genome, but instead is concentrated at regions of silent chromatin (4). This is consistent with various levels of RanGTP occurring in different regions of the genome. In light of our results, it is possible that a functional consequence of this nonrandom distribution of Prp20p would be the promotion of histone deposition preferentially at silent chromatin domains, which have higher levels of Prp20p/RanGTP.

We propose a model in which Kap114p imports H2A and H2B into the nucleus in a complex with Nap1p (Fig. 11, step 1). Although it would be in a RanGTP environment, Kap114p would not immediately release histones but would be inhibitory to their deposition and release until an appropriate target site had been encountered. The target site would necessarily be a region with a high concentration of RanGTP, but additional factors may also be necessary to stimulate Kap-histone dissociation. Free histones are toxic to cells, and hence mechanisms exist which help cells to dispose of them (8, 12, 34). Having a karyopherin which reversibly prevents histone release may serve a similar purpose. We speculate that the additional factor may be a protein at the replication fork or, possibly, H3-H4 tetramers already assembled onto the DNA. Most histone H2A and H2B is synthesized in S phase and assembled onto DNA at replication. It will be interesting to determine whether RanGTP itself is concentrated at the replication fork. It is known that H3 and H4 are deposited prior to H2A and H2B during DNA replication (14). Ran, regardless of its nucleotide state, binds preferentially to H3 and H4 (3), and therefore, during replication the initial deposition of H3 and H4 may recruit RanGTP. A high local concentration of RanGTP may promote the recruitment of Kap114p and subsequent H2A and H2B deposition by Nap1p (Fig. 11, steps 2 and 3). The deposition of H2A and H2B would then also promote the binding of RCC1. This would generate more RanGTP and further histone deposition in this domain, nucleating a self-enhancing system. It has also been shown that histones H2A and H2B are removed from nucleosomes in a replication-independent manner associated with transcriptional activation (2); these histones would necessarily require redeposition. It is possible that Nap1p also participates in this process and that this activity is modulated by Kap114p and the Ran system as described above.

FIG. 11.

Proposed model for the function of Kap114p and RanGTP in histone deposition. See Discussion for details.

In summary, our results support the notion that karyopherins have other functions besides serving as nuclear transport receptors. Here we showed that a karyopherin can regulate the function of the evolutionarily conserved H2A and H2B chaperone Nap1p. This establishes an important paradigm, as most nuclear proteins interact with karyopherins. The spatial and temporal regulation of this interaction by karyopherins and RanGTP may serve to determine when and where a particular nuclear protein can function. If so, a new, hitherto unexplored level of regulation may exist for countless nuclear proteins.

Acknowledgments

We thank those individuals cited in the text for reagents. We thank P. Todd Stukenberg for help with the Xenopus sperm chromatin assay system, as well as M. Mitch Smith, Ian Macara, David Wotton, and members of the Pemberton and Macara labs for discussions on the manuscript.

N.M. was supported by an NIH Cell and Molecular Biology training grant. This work was supported by research grant R01 GM65385 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aitchison, J. D., G. Blobel, and M. P. Rout. 1996. Kap104p: a karyopherin involved in the nuclear transport of messenger RNA binding proteins. Science 274:624-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belotserkovskaya, R., and D. Reinberg. 2004. Facts about FACT and transcript elongation through chromatin. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 14:139-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bilbao-Cortes, D., M. Hetzer, G. Langst, P. B. Becker, and I. W. Mattaj. 2002. Ran binds to chromatin by two distinct mechanisms. Curr. Biol. 12:1151-1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casolari, J. M., C. R. Brown, S. Komili, J. West, H. Hieronymus, and P. A. Silver. 2004. Genome-wide localization of the nuclear transport machinery couples transcriptional status and nuclear organization. Cell 117:427-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang, L., S. S. Loranger, C. Mizzen, S. G. Ernst, C. D. Allis, and A. T. Annunziato. 1997. Histones in transit: cytosolic histone complexes and diacetylation of H4 during nucleosome assembly in human cells. Biochemistry 36:469-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dasso, M. 2001. Running on Ran: nuclear transport and the mitotic spindle. Cell 104:321-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dasso, M., T. Seki, Y. Azuma, T. Ohba, and T. Nishimoto. 1994. A mutant form of the Ran/TC4 protein disrupts nuclear function in Xenopus laevis egg extracts by inhibiting the RCC1 protein, a regulator of chromosome condensation. EMBO J. 13:5732-5744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dominski, Z., X. C. Yang, H. Kaygun, M. Dadlez, and W. F. Marzluff. 2003. A 3′ exonuclease that specifically interacts with the 3′ end of histone mRNA. Mol. Cell 12:295-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finley, D., E. Ozkaynak, and A. Varshavsky. 1987. The yeast polyubiquitin gene is essential for resistance to high temperatures, starvation, and other stresses. Cell 48:1035-1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldstein, A. L., and J. H. McCusker. 1999. Three new dominant drug resistance cassettes for gene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 15:1541-1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gontijo, A. M., C. M. Green, and G. Almouzni. 2003. Repairing DNA damage in chromatin. Biochimie 85:1133-1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gunjan, A., and A. Verreault. 2003. A Rad53 kinase-dependent surveillance mechanism that regulates histone protein levels in S. cerevisiae. Cell 115:537-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harel, A., R. C. Chan, A. Lachish-Zalait, E. Zimmerman, M. Elbaum, and D. J. Forbes. 2003. Importin beta negatively regulates nuclear membrane fusion and nuclear pore complex assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell 14:4387-4396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haushalter, K. A., and J. T. Kadonaga. 2003. Chromatin assembly by DNA-translocating motors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4:613-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hetzer, M., D. Bilbao-Cortes, T. C. Walther, O. J. Gruss, and I. W. Mattaj. 2000. GTP hydrolysis by Ran is required for nuclear envelope assembly. Mol. Cell 5:1013-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishimi, Y., and A. Kikuchi. 1991. Identification and molecular cloning of yeast homolog of nucleosome assembly protein I which facilitates nucleosome assembly in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 266:7025-7029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito, T. 2003. Nucleosome assembly and remodeling. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 274:1-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito, T., J. K. Tyler, M. Bulger, R. Kobayashi, and J. T. Kadonaga. 1996. ATP-facilitated chromatin assembly with a nucleoplasmin-like protein from Drosophila melanogaster. J. Biol. Chem. 271:25041-25048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito, T., J. K. Tyler, and J. T. Kadonaga. 1997. Chromatin assembly factors: a dual function in nucleosome formation and mobilization? Genes Cells 2:593-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee, D. C., and J. D. Aitchison. 1999. Kap104p-mediated nuclear import. Nuclear localization signals in mRNA-binding proteins and the role of Ran and Rna. J. Biol. Chem. 274:29031-29037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lounsbury, K. M., S. A. Richards, K. L. Carey, and I. G. Macara. 1996. Mutations within the Ran/TC4 GTPase. Effects on regulatory factor interactions and subcellular localization. J. Biol. Chem. 271:32834-32841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma, X. J., J. Wu, B. A. Altheim, M. C. Schultz, and M. Grunstein. 1998. Deposition-related sites K5/K12 in histone H4 are not required for nucleosome deposition in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:6693-6698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mosammaparast, N., C. S. Ewart, and L. F. Pemberton. 2002. A role for nucleosome assembly protein 1 in the nuclear transport of histones H2A and H2B. EMBO J. 21:6527-6538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mosammaparast, N., Y. Guo, J. Shabanowitz, D. F. Hunt, and L. F. Pemberton. 2002. Pathways mediating the nuclear import of histones H3 and H4 in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 277:862-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mosammaparast, N., K. R. Jackson, Y. Guo, C. J. Brame, J. Shabanowitz, D. F. Hunt, and L. F. Pemberton. 2001. Nuclear import of histone H2A and H2B is mediated by a network of karyopherins. J. Cell Biol. 153:251-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nemergut, M. E., C. A. Mizzen, T. Stukenberg, C. D. Allis, and I. G. Macara. 2001. Chromatin docking and exchange activity enhancement of RCC1 by histones H2A and H2B. Science 292:1540-1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pemberton, L. F., J. S. Rosenblum, and G. Blobel. 1997. A distinct and parallel pathway for the nuclear import of an mRNA-binding protein. J. Cell Biol. 139:1645-1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pemberton, L. F., J. S. Rosenblum, and G. Blobel. 1999. Nuclear import of the TATA-binding protein: mediation by the karyopherin Kap114p and a possible mechanism for intranuclear targeting. J. Cell Biol. 145:1407-1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Philpott, A., and G. H. Leno. 1992. Nucleoplasmin remodels sperm chromatin in Xenopus egg extracts. Cell 69:759-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Philpott, A., G. H. Leno, and R. A. Laskey. 1991. Sperm decondensation in Xenopus egg cytoplasm is mediated by nucleoplasmin. Cell 65:569-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schlenstedt, G., E. Smirnova, R. Deane, J. Solsbacher, U. Kutay, D. Görlich, H. Ponstingl, and F. R. Bischoff. 1997. Yrb4p, a yeast Ran-GTP-binding protein involved in import of ribosomal protein L25 into the nucleus. EMBO J. 16:6237-6249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Senger, B., G. Simos, F. R. Bischoff, A. Podtelejnikov, M. Mann, and E. Hurt. 1998. Mtr10p functions as a nuclear import receptor for the mRNA-binding protein Npl3p. EMBO J. 17:2196-2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sobel, R. E., R. G. Cook, C. A. Perry, A. T. Annunziato, and C. D. Allis. 1995. Conservation of deposition-related acetylation sites in newly synthesized histones H3 and H4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:1237-1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sutton, A., J. Bucaria, M. A. Osley, and R. Sternglanz. 2001. Yeast ASF1 protein is required for cell cycle regulation of histone gene transcription. Genetics 158:587-596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tyler, J. K. 2002. Chromatin assembly. Cooperation between histone chaperones and ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling machines. Eur. J. Biochem. 269:2268-2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tyler, J. K., C. R. Adams, S. R. Chen, R. Kobayashi, R. T. Kamakaka, and J. T. Kadonaga. 1999. The RCAF complex mediates chromatin assembly during DNA replication and repair. Nature 402:555-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verreault, A., P. D. Kaufman, R. Kobayashi, and B. Stillman. 1996. Nucleosome assembly by a complex of CAF-1 and acetylated histones H3/H4. Cell 87:95-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walther, T. C., P. Askjaer, M. Gentzel, A. Habermann, G. Griffiths, M. Wilm, I. W. Mattaj, and M. Hetzer. 2003. RanGTP mediates nuclear pore complex assembly. Nature 424:689-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weis, K. 2003. Regulating access to the genome: nucleocytoplasmic transport throughout the cell cycle. Cell 112:441-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]