Abstract

The stability of cell cycle checkpoint and regulatory proteins is controlled by the ubiquitin-proteasome degradation machinery. A critical regulator of cell cycle molecules is the E3 ubiquitin ligase SCFSkp2, known to facilitate the polyubiquitination and degradation of p27, E2F, and c-myc. SCFSkp2 is frequently deregulated in human cancers. In this study, we have revealed a novel link between the essential Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) nuclear antigen EBNA3C and the SCFSkp2 complex, providing a mechanism for cell cycle regulation by EBV. EBNA3C associates with cyclin A/cdk2 complexes, disrupting the kinase inhibitor p27 and enhancing kinase activity. The recruitment of SCFSkp2 activity to cyclin A complexes by EBNA3C results in ubiquitination and SCFSkp2-dependent degradation of p27. This is the first report of a viral protein usurping the function of the SCFSkp2 cell cycle regulatory machinery to regulate p27 stability, establishing the foundation for a mechanism by which EBV regulates cyclin/cdk activity in human cancers.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is the etiologic agent of most cases of infectious mononucleosis, a syndrome resulting from a dramatic increase in CD8 T-cell activation in response to EBV infection and expansion of B lymphocytes (17, 37). This clinical manifestation of primary EBV infection highlights the ability of the virus not only to establish latent infection in B lymphocytes but also to drive lymphocyte proliferation in vivo. In addition, EBV potently transforms B cells in vitro and contributes to numerous lymphoid malignancies in humans, including Burkitt's lymphoma, Hodgkin's lymphoma, and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease (17, 37). Transformation of B lymphocytes by EBV has been attributed to the expression of a growth stimulatory program by the virus. Four viral antigens have been shown to be absolutely essential for B-cell transformation: EBNA2, LMP1, EBNA3A, and EBNA3C (8, 13, 16, 41). EBNA1 and EBNA-LP are critical but not essential for the immortalization process (25).

EBNA3C was initially described as a transcriptional regulator targeting RBP-Jκ and Spi-1/Spi-B transcription factors to regulate viral promoters such as Cp and LMP1 (2, 3, 46). EBNA3C has also been shown to play a role in histone acetylation as it apparently targets and regulates both histone acetyltransferase activity and histone deacetylase complexes, including HDAC1, HDAC2, and the corepressors mSin3a and NcoR (19, 36, 40). More recently, it has become apparent that EBNA3C plays a role in deregulation of the cell cycle by EBV. EBNA3C regulates transcription of the EBV oncogene LMP1 in a cell cycle-dependent manner and targets Rb-E2F regulatory pathways leading to the accumulation of cells in the S/G2 phase of the cell cycle (3, 32, 33). Recently, we demonstrated that EBNA3C targets cyclin A complexes in cells and enhances cyclin A-dependent kinase activity by disrupting the cdk inhibitor p27 from kinase complexes (20).

In this report, we demonstrate that, in addition to targeting cyclin A, EBNA3C targets the SCFSkp2 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. Components of SCFSkp2, Skp1 and Skp2, were initially identified as S-phase kinase-associated proteins that complex with cyclin A in tumor cells but not primary cells (45). Subsequently, it was demonstrated that the SCFSkp2 complex consists of additional core components, Cul1 and Roc1, and that this complex plays a critical role in regulating the stability of diverse cell cycle proteins which include p27, E2F, and c-myc (6, 18, 26, 44). SCFSkp2 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase functionally linking specific substrates to the ubiquitin-activating and ubiquitin-conjugating machinery (5). This link targets substrates for polyubiquitination and ultimately degradation by the 26S proteasome (5). SCFSkp2 is perhaps the best-studied member of the group of SCF E3 ligases, each with a unique F-box protein that confers substrate specificity (47). Skp2, containing a so-called F-box domain that facilitates its interaction with Skp1, is overexpressed in many diverse classes of human lymphomas and tumors and presumably contributes to the destabilization of p27 in these cancers (7, 12, 22, 23, 39). Here we demonstrate that EBNA3C regulates p27 stability by manipulating the oncoprotein Skp2 as well as other SCF components. Regulation of p27 stability by EBNA3C is most likely at the level of its interaction with cyclin A complexes, providing a potential mechanism by which EBNA3C disrupts p27 from cyclin A complexes and ultimately stimulates cyclin A-dependent kinase activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids, antibodies, and cell lines.

pA3M-EBNAC constructs express either full-length EBNA3C or EBNA3C truncations with a carboxy-terminal myc tag and have been described previously (9). Glutathione S-transferase (GST)-EBNA3C truncation mutants and pSG5-EBNA3C have been previously described (21). pCMV-Cdk2, RC-cyclin A, and RC-cyclin E were kindly provided by Philip Hinds (14). The construct expressing GST-cyclin A was provided by Maria Mudryj (10). pCDNA3-p27 and pCDNA3-Cks1-FL were provided by Michele Pagano (11, 31). pCDNA-myc-Skp2, pCDNA3-HA-Cul1, and pCDNA3-HA-Roc1 were provided by Yue Xiong (28, 30). Skp1 cDNA was provided by Stephen Elledge (5). pCDNA3-HA-Ub was provided by George Mosialos (42). Constructs expressing myc-tagged cyclin A, Skp1, p27, and p27 amino acids 1 to 185 were prepared by cloning PCR-amplified cDNAs into the previously described pA3M vector (4). Constructs expressing untagged Skp1 and Skp2 and hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged Roc1 amino acids 36 to 108 were prepared by cloning PCR-amplified cDNAs into the pCDNA3.1 vector (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, Calif.). C53A/C56A point mutations in the Roc1 gene were prepared by a standard PCR primer mutagenesis method. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies reactive to cyclin A, cdk2, Skp2, Cul1, and p27 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, Calif.). A10 monoclonal antibody reactive to EBNA3C has been previously described (9). Mouse monoclonal antibody reactive to the HA tag was purchased from Covance Research Products, Inc. (Berkeley, Calif.). HEK 293 cells are human embryonic kidney cells transformed by adenovirus type 5 DNA; HEK 293T cells stably express the simian virus 40 large-T antigen (1). U2OS is a human osteosarcoma cell line (34). HEK 293, 293T, U2OS, and HeLa cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen Corporation) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum unless otherwise indicated. HEK 293T cells were transfected by electroporation at 210 V and 975 μF in a 0.4-μm gap cuvette. Lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) were maintained in RPMI (Invitrogen Corporation) supplemented the same as Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium.

GST pull-down assays.

GST fusion proteins were purified from bulk Escherichia coli cultures following induction with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) as described previously (9). For pull-down assays from cell lysates, lysates were prepared in radioimmunoprecipitation (RIPA) buffer (0.5% NP-40, 10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, supplemented with protease inhibitors). Lysates were precleared and then rotated with either GST control or the appropriate GST fusion protein bound to glutathione-Sepharose beads. For in vitro binding experiments, GST fusion proteins were incubated with 35S-labeled, in vitro-translated protein in binding buffer (1× phosphate-buffered saline [PBS], 0.1% NP-40, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 10% glycerol, supplemented with protease inhibitors). In vitro translation was done with the TNT T7 quick-coupled transcription/translation system (Promega Corporation, Madison, Wis.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunoprecipitation and immunofluorescence.

For transfected HEK 293T samples, cells were lysed on ice in 500 μl of RIPA buffer (0.5% NP-40, 10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, supplemented with protease inhibitors). For LCLs, 100 million viable cells were lysed in 1 ml of RIPA buffer. Lysates were precleared with either normal rabbit or normal mouse serum and then rotated with 1 μg of specific antibody for 4 h at 4°C. Immune complexes were precipitated with a 1:1 mixture of protein A- and protein G-Sepharose beads. Samples were washed, fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and then transferred to a 0.45-μm nitrocellulose membrane for Western blotting. Detection was done according to a standard chemiluminescence protocol unless otherwise indicated.

HeLa cells were transfected by Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen Corporation) with pA3M-EBNA3C and pCDNA3-Skp2. Cells were harvested at 24 h, trypsinized, and allowed to adhere to glass slides overnight. Cells were fixed and permeabilized in methanol at −20°C for 10 min followed by acetone at room temperature for 30 s. Slides were blocked with 5% goat serum and incubated at 4°C overnight with primary antibodies (1:100 9E10 myc ascites fluid, 5 μg of Skp2 rabbit polyclonal antibody/ml). Slides were washed with PBS and then incubated with AlexaFluor goat anti-mouse (594 nm) and goat anti-rabbit (488 nm) antibodies (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, Oreg.). Slides were washed and visualized with a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope.

Histone H1 kinase assay.

U2OS cells were seeded into six-well plates and grown to confluence in 0.5% fetal bovine serum for 48 h prior to transfection. Cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen Corporation), harvested after 24 h with a cell scraper, washed with PBS, and lysed on ice in 500 μl of RIPA buffer (0.5% NP-40, 10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, with protease and phosphatase inhibitors). Lysates were precleared and then rotated with 1 μg of cyclin A antibody overnight at 4°C. Cyclin A complexes were captured by rotating with protein A-Sepharose beads and washed with RIPA buffer. Cyclin A complexes were then washed with histone buffer (25 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 70 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, with protease and phosphatase inhibitors). Complexes were incubated in 30 μl of histone wash buffer supplemented with 4 μg of histone H1 (Upstate USA, Inc., Chicago, Ill.), 10 mM cold ATP, and 0.2 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP/μl for 30 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by adding SDS-lysis buffer and heating to 95°C for 10 min. Labeled histone H1 was resolved by SDS-12% PAGE. Quantitation was done with ImageQuant software (Amersham Biosciences Corporation, Piscataway, N.J.).

HEK 293T ubiquitination assay.

Ten million HEK 293T cells were transfected by electroporation (as described above) with 10 μg of pCDNA3-HA-Ub and 10 μg of a myc-tagged expression plasmid for EBNA3C, p27, Skp2, or Skp1. In some cases, cells were additionally transfected with 10 μg of pSG5-E3C or 10 μg of pCDNA3-HA-Roc1 as indicated. Cells were harvested at 36 h, lysed in RIPA buffer (see above), immunoprecipitated with 9E10 myc-specific ascites fluid, and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Ubiquitin-tagged proteins were detected by HA-specific Western blot analysis.

p27 degradation assay.

The degradation reaction consisted of 20 μl of concentrated BJAB extract, 10 μl of in vitro-translated p27, 10 mM ATP, and SCFSkp2 complex immunoprecipitated from HEK 293T cells in a total volume of 40 μl. Samples were incubated at 30°C and mixed every 30 min. Five-microliter samples were harvested, mixed with 25 μl of SDS loading buffer, and heated at 95°C for 7 min. Concentrated BJAB extracts were prepared by washing cells in PBS and then resuspending them in 0.5 volumes (relative to pellet) of low-salt buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 2 μg [each] of aprotinin, pepstatin, and leupeptin/ml). Cells were sonicated with four 10-s pulses, and cell debris was removed by centrifugation. Glycerol was added to 10%, and samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use. In vitro translation was with a rabbit reticulocyte-based kit from Promega. For immunoprecipitation of SCFSkp2complexes, 20 million HEK 293T cells were transfected by electroporation (as described above) with 10 μg (each) of pCDNA3-myc-Skp2, pCDNA3-HA-Cul1, pCR3.1-Skp1, pCDNA3-HA-Roc1, and pCDNA3-Cks1-FL and 15 μg of pSG5-E3C, as indicated. Samples were harvested at 36 h, lysed in RIPA buffer (see above), and immunoprecipitated with 9E10 myc-specific ascites fluid overnight, followed by a 1:1 mixture of protein A- and protein G-Sepharose beads for 2 h.

Proteasome inhibition of LCLs with MG-132.

A recently immortalized LCL was passaged every 24 h for several days to establish an asynchronous population of cells. Cells were then treated with either dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) control or 10 μg of MG-132 (Calbiochem Biochemicals)/ml for up to 8 h. Lysates were prepared and normalized by Bradford assay. Samples were resolved by SDS-10% PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane for Western blotting. After incubation with primary antibody, bands were visualized by incubation with conjugated secondary antibodies which fluoresce in the infrared region of the spectrum (Alexa Fluor 680). Direct detection of the fluorescence and quantification was done with the Li-Cor Odyssey (Lincoln, Nebr.).

RESULTS

Previously, we demonstrated that EBNA3C disrupts p27 from cyclin A complexes and that EBNA3C rescues p27-mediated suppression of cyclin A-dependent kinase activity. These data were consistent with a model whereby EBNA3C directly competes with p27 for cyclin A binding (20). However, to date, we have been unable to demonstrate competition between p27 and EBNA3C for cyclin A binding in vitro. This suggests that EBNA3C may employ a more complex mechanism to regulate cyclin A/p27 complexes.

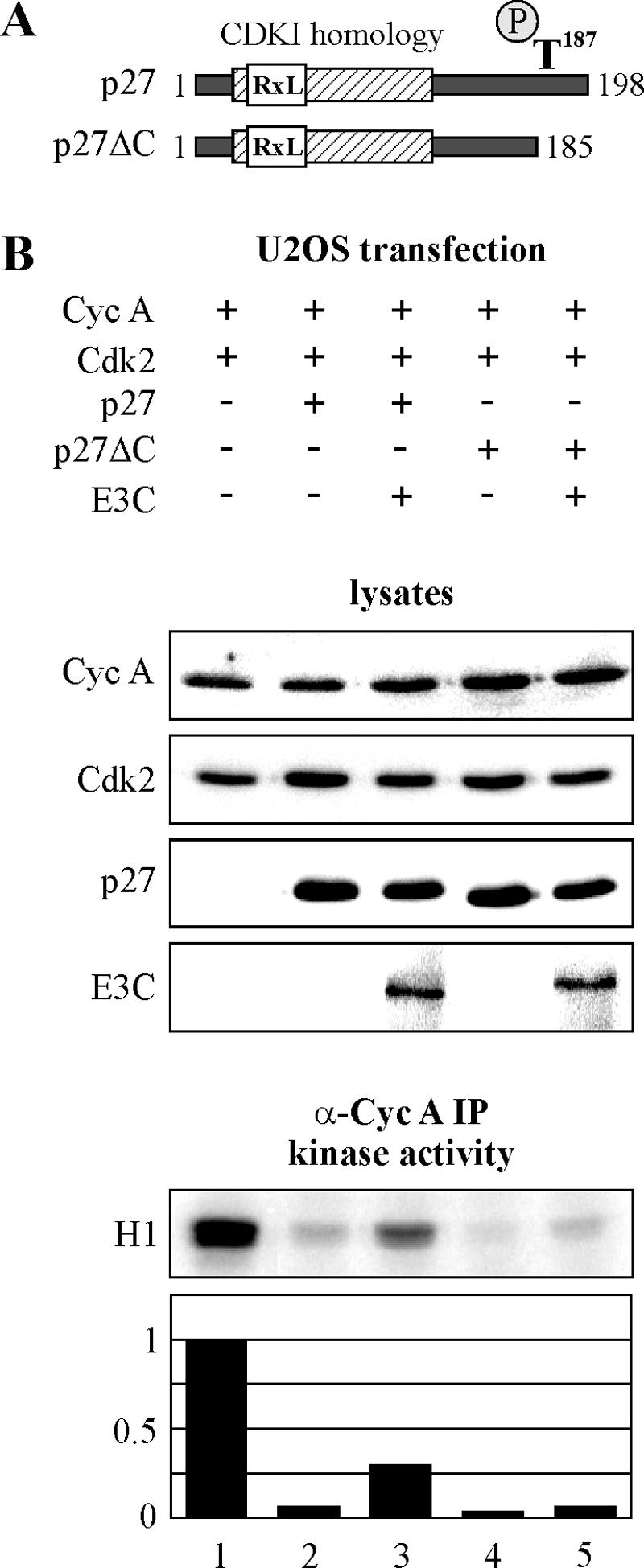

Inhibition of kinase activity by carboxy-terminally deleted p27 is not rescued by EBNA3C.

Previously, we demonstrated that EBNA3C stimulates cyclin A-dependent kinase activity in the osteosarcoma cell line U2OS and that EBNA3C rescues p27-mediated suppression of this activity in both U2OS and BJAB cell lines (20). Here, we demonstrate that deletion of the carboxy-terminal 13 amino acids of p27, including the regulatory amino acid threonine-187, eliminates the ability of EBNA3C to rescue kinase activity (Fig. 1A). U2OS cells were transfected with cyclin A, cdk2, p27, and EBNA3C expression constructs as indicated (Fig. 1B). At 24 h, cyclin A complexes were immunoprecipitated and incubated with [32P]ATP and histone H1 substrate. In repeated experiments, EBNA3C was able to rescue inhibition of kinase activity by p27 5- to 10-fold, while no reproducible rescue was seen for carboxy-terminally truncated p27 in spite of its efficient inhibition of kinase activity (Fig. 1B, compare lanes 2 and 3 with 4 and 5). This carboxy-terminal region of p27 is notable for the critical residue threonine-187, which regulates p27 stability (Fig. 1A). Phosphorylation of this residue by cyclin A/cdk2 and other kinase complexes such as cyclin E/cdk2 promotes recognition of p27 by the SCFSkp2 complex, resulting in polyubiquitination and ultimately degradation of p27 (29, 43). Thus, threonine-187 is likely critical for EBNA3C-mediated rescue of kinase activity.

FIG. 1.

Deletion of the p27 carboxy terminus eliminates EBNA3C rescue of kinase activity. (A) This schematic shows deletion of the carboxy-terminal 13 residues of p27. Phosphorylation on threonine-187 is a critical regulator of p27 stability via the SCFSkp2 complex. (B) U2OS cells were transfected with (+) expression constructs for cyclin A (Cyc A), Cdk2, full-length p27, p27 with a deletion of the carboxy-terminal 13 residues, and EBNA3C (E3C), as indicated. After 24 h, cyclin A immunoprecipitates were captured and assayed for in vitro kinase activity toward histone H1. Western blotting demonstrates protein expression in cell lysates prior to immunoprecipitation (IP). Quantification of kinase activity was done with ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics). α-Cyc A, anti-cyclin A; −, without.

EBNA3C is associated with ubiquitination activity and is itself ubiquitinated.

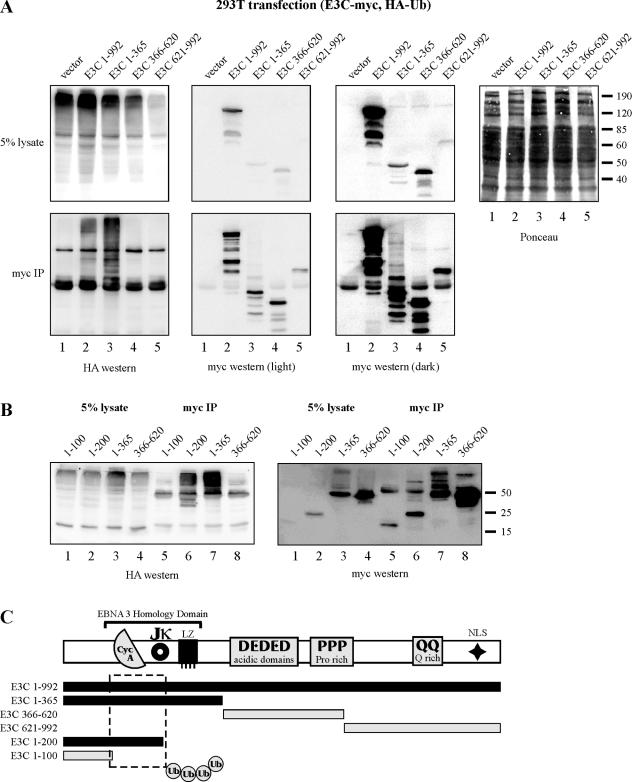

Studies have shown that phosphorylation of threonine-187 stimulates recognition and degradation of p27 by the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway (29, 43). We therefore wanted to determine whether EBNA3C recruits ubiquitination activity in cells and, additionally, whether EBNA3C itself may be ubiquitinated. HEK 293T cells, known to prominently express the SCFSkp2 complex which regulates p27 stability (6), were transfected with expression constructs for HA-tagged ubiquitin and myc-tagged EBNA3C or EBNA3C truncation mutants, as indicated (Fig. 2A). myc-specific immunoprecipitation resulted in the coimmunoprecipitation of high-molecular-weight ubiquitin-tagged proteins from cells expressing both full-length EBNA3C and a carboxy-terminally deleted EBNA3C, amino acids 1 to 365 (Fig. 2A, bottom left panel, lanes 2 and 3). These ubiquitin-tagged species were seen predominantly at higher molecular weights than full-length EBNA3C and EBNA3C amino acids 1 to 365, respectively. And, importantly, some of these species were also reactive with the myc-specific Western blot analysis (Fig. 2A). The aforementioned observations strongly suggest that these species represent polyubiquitinated EBNA3C and that this ubiquitination can be recapitulated by the first 365 amino acids of EBNA3C (Fig. 2A, lower panels, lanes 2 and 3). In vector control, EBNA3C amino acids 366 to 620 and EBNA3C amino acids 621 to 992 samples, no ubiquitinated species were precipitated by myc-specific antibody (Fig. 2A, left panel, lanes 1, 4, and 5).

FIG. 2.

EBNA3C associates with ubiquitination activity and is itself ubiquitinated. (A) HEK 293T cells were transfected with expression plasmids for HA-tagged ubiquitin (Ub) and myc-tagged EBNA3C (E3C) or EBNA3C truncations, as indicated. Cells were harvested at 36 h, and total protein was immunoprecipitated (IP) with myc-specific antibody. Samples were resolved by SDS-10% PAGE. Western blotting was done by stripping and reprobing the same membrane. (B) HEK 293T cells were transfected with expression plasmids for HA-tagged ubiquitin and myc-tagged EBNA3C truncations, as indicated. Cells were harvested at 36 h, and total protein was immunoprecipitated with myc-specific antibody. Samples were resolved by SDS-10% PAGE. Western blotting was done by stripping and reprobing the same membrane. (C) Schematic of EBNA3C demonstrating a region of the molecule that is essential for ubiquitination.

EBNA3C ubiquitination is dependent on amino acids 101 to 200.

To further define the region or regions of EBNA3C that recruit this ubiquitination activity, additional truncation mutants EBNA3C amino acids 1 to 100 and EBNA3C amino acids 1 to 200 were transfected into HEK 293T cells and assayed as above. Interestingly, amino acids 1 to 100 were not ubiquitinated, while amino acids 1 to 200 were potently ubiquitinated similar to amino acids 1 to 365 and full-length EBNA3C (Fig. 2B, lanes 5 to 7). This result suggests that EBNA3C amino acids 1 to 200 are sufficient to facilitate ubiquitination, with essential residues for this phenotype residing between amino acids 101 and 200 (Fig. 2C).

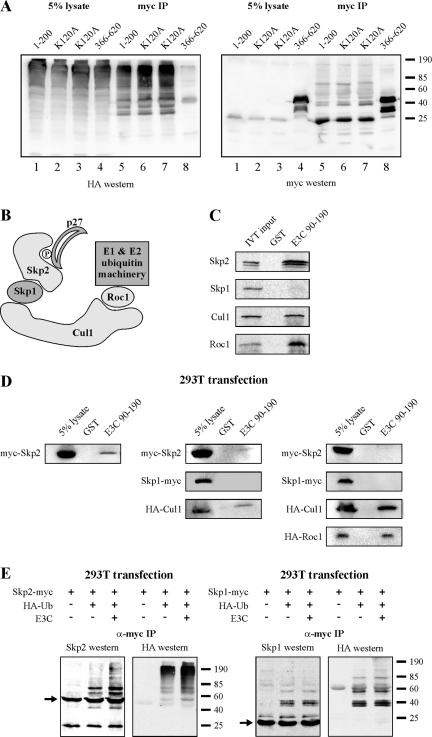

Lysine-120 is dispensable for the ubiquitination of EBNA3C amino acids 1 to 200.

At least two scenarios could explain the above data demonstrating that EBNA3C amino acids 101 to 200 are essential for ubiquitination. First, EBNA3C amino acids 101 to 200 may contain a critical lysine residue that accepts the polyubiquitin chain. Alternatively, EBNA3C amino acids 101 to 200 may recruit factors and ubiquitination machinery essential for formation of the polyubiquitin chain. The first possibility was easily addressed, as there is a single lysine residue within EBNA3C amino acids 101 to 200 (38). Mutation of lysine-120 to an alanine had no effect on the ubiquitination of EBNA3C amino acids 1 to 200 with two independent clones of this truncation (Fig. 3A, lanes 5 to 7). This result suggests that, instead of providing a critical ubiquitin acceptor, EBNA3C amino acids 101 to 200 likely recruit the enzymatic factors essential for ubiquitination of the EBNA3C molecule.

FIG. 3.

EBNA3C amino acids 90 to 190 recruit SCFSkp2 core components. (A) HEK 293T cells were transfected with expression plasmids for HA-tagged ubiquitin and myc-tagged EBNA3C truncations, as indicated. Cells were harvested at 36 h, and total protein was immunoprecipitated (IP) with myc-specific antibody. Samples were resolved by SDS-10% PAGE. Western blotting was done by stripping and reprobing the same membrane. (B) Schematic of the SCFSkp2 complex. (C) Expression plasmids for Skp2, Skp1, Cul1, and Roc1 were in vitro translated (IVT) and individually incubated with either GST or GST-EBNA3C amino acids 90 to 190 prebound to glutathione-Sepharose beads. (D) HEK 293T cells were transfected with expression plasmids for myc-tagged Skp2 (left column); myc-tagged Skp2, myc-tagged Skp1, and HA-tagged Cul1 (middle column); or myc-tagged Skp2, myc-tagged Skp1, HA-tagged Cul1, and HA-tagged Roc1 (right column). Cells were harvested at 36 h, and total protein was incubated with either GST or GST-EBNA3C amino acids 90 to 190 prebound to glutathione-Sepharose beads. (E) HEK 293T cells were transfected with expression plasmids for HA-tagged ubiquitin, untagged EBNA3C, and either myc-tagged Skp2 or myc-tagged Skp1, as indicated. Cells were harvested at 36 h, and total protein was immunoprecipitated with myc-specific antibody. Samples were resolved by SDS-12% PAGE. Western blotting was done by stripping and reprobing the same membrane. +, with; −, without; α-myc, anti-myc.

EBNA3C amino acids 90 to 190 recruit components of the SCFSkp2 ubiquitin ligase complex.

As we had demonstrated above that EBNA3C regulation of cyclin A/p27 complexes is dependent upon the SCFSkp2-binding motif of p27, we decided to test whether EBNA3C interacts with SCFSkp2 in a manner that recruits ubiquitination activity to EBNA3C (Fig. 3B). We demonstrated above that EBNA3C amino acids 101 to 200 may contain an essential domain for the recruitment of ubiquitination machinery; to test whether this region of EBNA3C binds SCFSkp2, we prepared a GST fusion protein of EBNA3C corresponding to amino acids 90 to 190, shown previously to interact with cyclin A, and tested whether individual in vitro-translated SCF components bind to this region of EBNA3C (Fig. 3C). EBNA3C amino acids 90 to 190 strongly precipitated Skp2, Cul1, and Roc1, but not Skp1, when the proteins were expressed individually (Fig. 3C). To confirm that the precipitation of these species was not the result of their mutual association with ubiquitin, we also tested whether this region of EBNA3C may directly bind the 76-amino-acid ubiquitin protein. Importantly, EBNA3C amino acids 90 to 190 did not bind to monoubiquitin by an in vitro binding assay, nor did they nonspecifically precipitate high-molecular-weight ubiquitin chains from transfected cell lysates (data not shown).

As multiple components of SCFSkp2 bound EBNA3C in the above in vitro binding assay, we tested whether these molecules may cooperate or compete for binding to EBNA3C in cells. EBNA3C amino acids 90 to 190 precipitated myc-tagged Skp2 from singly transfected cell lysates (Fig. 3D, left panel). Interestingly, as additional components of SCFSkp2 were expressed, the interaction between EBNA3C amino acids 90 to 190 and Skp2 was reduced (Fig. 3D, right two panels). Indeed, with expression of myc-tagged Skp1 and HA-tagged Cul1, Skp2 was only weakly precipitated by EBNA3C amino acids 90 to 190, and Cul1 was also precipitated (Fig. 3D, middle panel). With the further addition of HA-tagged Roc1, Cul1 and Roc1 formed a strong complex with EBNA3C amino acids 90 to 190 and the Skp2 interaction was abolished to undetectable levels (Fig. 3D, right panel).

As it is known that F-box proteins are themselves ubiquitinated and may enter only transiently into SCF complexes (48), the above data suggest that EBNA3C may be capable of assembling active SCF ubiquitin ligase complexes. This potentially explains why Skp2 binding to EBNA3C was abolished with the recruitment of additional SCF components Cul1 and Roc1. To test whether EBNA3C recruits ubiquitination activity to Skp2 complexes, an expression plasmid for myc-tagged Skp2 was transfected into HEK 293T cells along with expression plasmids for HA-tagged ubiquitin and EBNA3C (Fig. 3E). Cells were then lysed, and Skp2 complexes were immunoprecipitated with myc-specific monoclonal antibody. Western blotting with either Skp2 or HA antibodies demonstrated enhanced ubiquitin-tagged Skp2 in the presence of EBNA3C (Fig. 3E, left panels). As a control, we also tested Skp1 ubiquitination in a similar HEK 293T transfection background (Fig. 3E, right panel). While low-molecular-weight ubiquitinated forms of Skp1 were easily detected, they were not enhanced by EBNA3C expression (Fig. 3E, right panel). We did detect some high-molecular-weight ubiquitinated species in the EBNA3C sample by HA Western blotting (Fig. 3E, right panel, rightmost lane); however, these species were not reactive with the Skp1-specific Western blot and likely represent an unidentified protein that coimmunoprecipitates with Skp1.

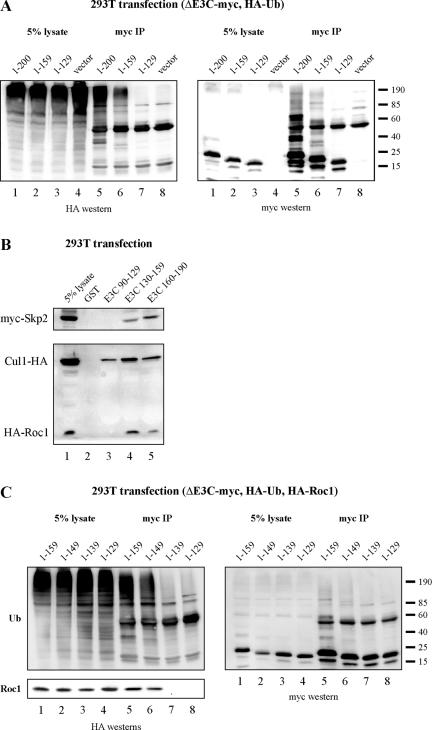

EBNA3C ubiquitination and SCFSkp2 recruitment are dependent upon EBNA3C amino acids 130 to 190.

To more precisely define the region of EBNA3C that recruits ubiquitination activity, additional expression plasmids corresponding to EBNA3C amino acids 1 to 159 and 1 to 129 were constructed. These plasmids, along with EBNA3C amino acids 1 to 200, were transfected into HEK 293T cells and assayed for the formation of HA-ubiquitin chains. As was shown above, EBNA3C amino acids 1 to 200 were strongly ubiquitinated (Fig. 4A, lane 5). EBNA3C amino acids 1 to 159 were reproducibly ubiquitinated to a lesser extent than amino acids 1 to 200, and EBNA3C amino acids 1 to 129 were not ubiquitinated (Fig. 4A, lanes 6 and 7). This suggests that EBNA3C amino acids 130 to 159 likely comprise the predominant ubiquitination recruitment domain, while residues which lie within amino acids 160 to 200 may also be involved in regulation of this process. Importantly, neither of these regions contains a lysine residue.

FIG. 4.

EBNA3C amino acids 130 to 159 and 160 to 190 both contribute to EBNA3C ubiquitination and SCFSkp2 recruitment. (A) HEK 293T cells were transfected with expression plasmids for HA-tagged ubiquitin (Ub) and myc-tagged EBNA3C (E3C) truncations, as indicated. Cells were harvested at 36 h, and total protein was immunoprecipitated (IP) with myc-specific antibody. Samples were resolved by SDS-10% PAGE. Western blotting was done by stripping and reprobing the same membrane. (B) HEK 293T cells were transfected with either myc-tagged Skp2 or both HA-tagged Cul1 and HA-tagged Roc1 expression plasmids. Cells were harvested at 36 h, and total protein was incubated with either GST, GST-EBNA3C amino acids 90 to 129, GST-EBNA3C amino acids 130 to 159, or GST-EBNA3C amino acids 160 to 190 prebound to glutathione-Sepharose beads. (C) HEK 293T cells were transfected with expression plasmids for HA-tagged ubiquitin, HA-tagged Roc1, and myc-tagged EBNA3C truncations, as indicated. Cells were harvested at 36 h, and total protein was immunoprecipitated with myc-specific antibody. Samples were resolved by SDS-10% PAGE. Western blotting was done by stripping and reprobing the same membrane.

To test whether the regions 160 to 200 and 130 to 159 play a role in SCFSkp2 recruitment, GST pull-down assays were performed from cell lysates as above. HEK 293T cells were transfected either with Skp2 alone or with both Cul1 and Roc1. Skp2 was precipitated with GST fusion proteins corresponding to both EBNA3C amino acids 130 to 159 and 160 to 190, although reproducibly to a greater extent with amino acids 160 to 190 (Fig. 4B, top panel). In contrast, Cul1 and Roc1 both precipitated most strongly with EBNA3C amino acids 130 to 159 and to a lesser extent with amino acids 160 to 190 (Fig. 4B, lower panel). These cumulative data suggest that the SCFSkp2 binding domain likely encompasses multiple residues in amino acids 130 to 190, which is consistent with this being the primary domain responsible for the recruitment of ubiquitination activity.

EBNA3C ubiquitination and Roc1 recruitment are dependent upon EBNA3C amino acids 140 to 149.

Previous work has indicated that the RING finger protein Roc1 physically links the SCF core to the more basal E1 ubiquitin-activating and E2 ubiquitin-conjugating machinery and, consequently, is the minimal factor necessary for recruiting ubiquitination activity (15, 30). To test whether Roc1 recruitment is tightly linked to EBNA3C ubiquitination, HEK 293T cells were transfected with expression constructs encoding EBNA3C amino acids 1 to 159, 1 to 149, 1 to 139, and 1 to 129, each with a myc tag at the carboxy terminus (Fig. 4C). Cells were additionally transfected with expression constructs for HA-tagged ubiquitin and Roc1. While amino acids 1 to 159 and 1 to 149 recruited both Roc1 and ubiquitination activity, amino acids 1 to 139 and 1 to 129 recruited neither (Fig. 4C). This suggests that EBNA3C amino acids 140 to 149 represent a minimal domain for the recruitment of ubiquitination activity and that this activity is tightly linked to the recruitment of the RING finger protein Roc1 (Fig. 4C, lanes 6 and 7).

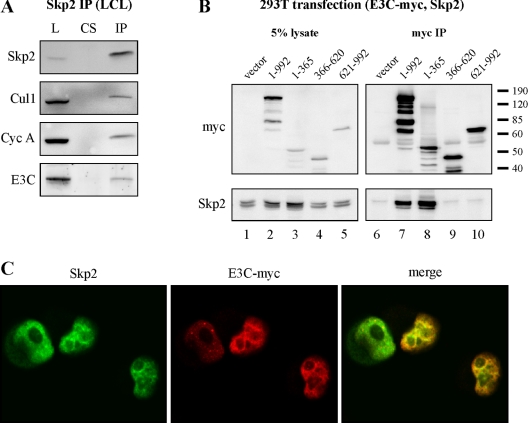

EBNA3C forms complexes with Skp2 in EBV-transformed B cells.

To test the association between SCFSkp2 and EBNA3C in virally infected cells, Skp2 was immunoprecipitated from a recently transformed LCL and coimmunoprecipitating species were assessed by Western blotting. As expected, antibody specific to Skp2 coimmunoprecipitated Skp2 and known Skp2-binding partners Cul1 and cyclin A (24, 28, 45) (Fig. 5A). EBNA3C was also coimmunoprecipitated at a level similar to that of Cul1 and cyclin A, suggesting that EBNA3C and Skp2 may form a functional complex in LCLs (Fig. 5A). The reverse coimmunoprecipitation experiment was performed by cotransfecting HEK 293T cells with myc-tagged EBNA3C and untagged Skp2 expression plasmids (Fig. 5B). As expected, Skp2 coimmunoprecipitated with both full-length EBNA3C and EBNA3C amino acids 1 to 365 by using an antibody specific to the myc tag (Fig. 5B, lanes 7 and 8).

FIG. 5.

EBNA3C (E3C) associates with Skp2 in cells. (A) One hundred million EBV-positive LCL cells were lysed in RIPA buffer, and protein complexes were immunoprecipitated with Skp2-specifc antibody. Samples were resolved by SDS-10% PAGE. Western blotting for the indicated proteins was done by stripping and reprobing the same membrane. L, 5% total protein lysate; CS, control serum; IP, anti-Skp2 immunoprecipitation. (B) HEK 293T cells were transfected with pCDNA3-Skp2, encoding untagged Skp2, and pA3M-EBNA3C, encoding either full-length EBNA3C or EBNA3C truncations, as indicated. All EBNA3C proteins were tagged with the myc epitope. Cells were harvested at 36 h and immunoprecipitated with myc-specific antibody. Samples were resolved by SDS-10% PAGE and probed by Western blotting. (C) HeLa cells were transfected with expression plasmids for full-length, myc-tagged EBNA3C and untagged Skp2. Cells were fixed and probed with anti-Skp2 rabbit polyclonal and anti-myc mouse monoclonal antibodies. Staining was visualized by confocal microscopy with goat anti-rabbit (green) and goat anti-mouse (red) antibodies.

To determine whether Skp2 and EBNA3C exist in similar nuclear compartments, HeLa cells were transfected with a vector expressing myc-tagged EBNA3C and untagged Skp2. Cells were then stained with antibodies specific for myc and Skp2, respectively, and nuclei were visualized by confocal microscopy to assess colocalization. EBNA3C staining was tightly nuclear, demonstrating a finely stippled pattern with exclusion of nucleoli (Fig. 5C, middle panel); Skp2 staining was similarly concentrated in the nucleus (Fig. 5C, right panel). Importantly, EBNA3C and Skp2 colocalized at numerous points in the visualized nuclear plane, as illustrated by yellow color in the merged image (Fig. 5C, right panel). These data corroborate the in vivo association between Skp2 and EBNA3C, as these molecules localize to similar compartments in the cell nucleus.

EBNA3C functionally associates with the RING finger protein Roc1.

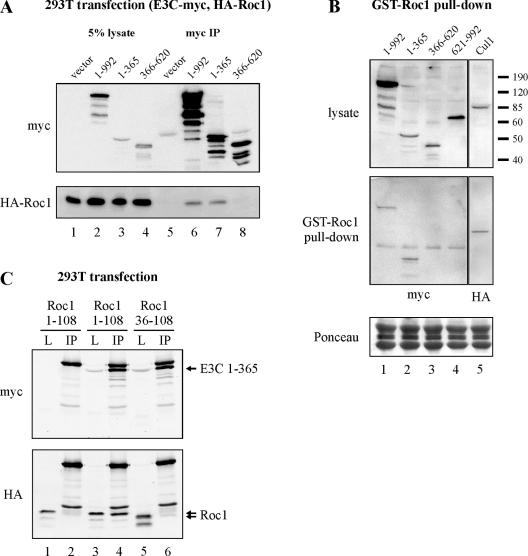

The EBNA3C/Roc1 association was assayed as for EBNA3C/Skp2 by coimmunoprecipitation in HEK 293T cells (Fig. 6A). Similar to Skp2, Roc1 coimmunoprecipitated with both full-length EBNA3C and EBNA3C amino acids 1 to 365 when both components were transiently transfected into HEK 293T cells (Fig. 6A, lanes 6 and 7). To corroborate this experiment, GST-tagged Roc1 pulled down full-length EBNA3C and EBNA3C amino acids 1 to 365, but not EBNA3C amino acids 366 to 620 or 621 to 992 (Fig. 6B). The efficiency of pull down was similar to that seen for a known Roc1-interacting protein, Cul1.

FIG. 6.

EBNA3C (E3C) associates with Roc1 in cells. (A) HEK 293T cells were transfected with pCDNA3-HA-Roc1, encoding Roc1 tagged with the HA epitope, and pA3M-EBNA3C, encoding either full-length EBNA3C or EBNA3C truncations, as indicated. All EBNA3C proteins were tagged with the myc epitope. Cells were harvested at 36 h and immunoprecipitated with myc-specific serum. Samples were resolved by SDS-10% PAGE and probed by Western blotting. (B) HEK 293T cells were transfected with expression plasmids either for myc-tagged EBNA3C truncations or for HA-tagged Cul1. Cells were harvested at 36 h, and total protein was incubated with either GST or GST-Roc1 prebound to glutathione-Sepharose beads. Samples were resolved by SDS-10% PAGE and probed by Western blotting. (C) HEK 293T cells were transfected with pA3M-EBNA3C amino acids 1 to 365, encoding EBNA3C amino acids 1 to 365 tagged with the myc epitope. Cells were also transfected with pCDNA3-HA-Roc1 or pCDNA3-HA-Roc1 amino acids 36 to 108, encoding full-length Roc1 or a truncated form of Roc1, respectively, both tagged with the HA epitope. Cells were harvested at 36 h and immunoprecipitated with myc-specific antibody. Samples were resolved by SDS-10% PAGE and probed by Western blotting. L, lysate; IP, immunoprecipitation.

Roc1 contains a RING finger motif which is responsible for the recruitment of E2 ubiquitin-conjugating activity to the SCFSkp2 ubiquitin ligase complex (30). The Roc1 RING finger motif conjugates three Zn2+ ions and occupies the carboxy-terminal two-thirds of this 108-amino-acid protein (47). To test whether this critical domain contributes to EBNA3C binding, we generated a Roc1 truncation mutant encompassing the entire RING finger motif, but with a deletion of the amino terminus of Roc1, which has previously been shown to mediate Cul1 binding (47). Interestingly, unlike full-length Roc1, Roc1 amino acids 36 to 108 did not coimmunoprecipitate with the amino terminus of EBNA3C, implicating Roc1 amino acids 1 to 35 in EBNA3C binding (Fig. 6C, compare lanes 3 and 4 with lanes 5 and 6). This result is consistent with EBNA3C binding Roc1 in a manner that leaves the RING finger motif available for ubiquitin recruitment.

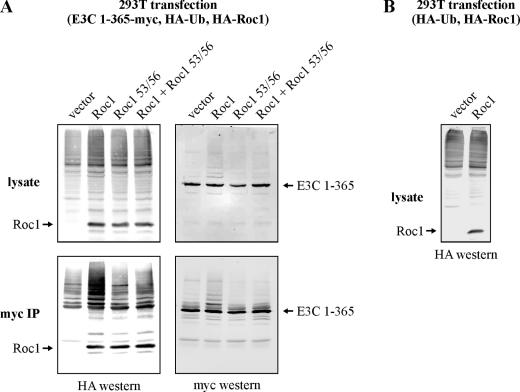

During the course of the aforementioned studies, we made the observation that the delivery of a Roc1 expression plasmid into EBNA3C-expressing cells significantly and reproducibly enhanced EBNA3C ubiquitination (Fig. 7A, lower left panel). As Roc1 binding to EBNA3C is not dependent on the well-characterized RING finger motif (Fig. 6C), we decided to test whether mutations in this motif would disrupt EBNA3C ubiquitination without affecting binding. Several specific RING finger mutations which disrupt Zn2+ coordination and, consequently, RING finger structure have been shown to significantly impair Roc1-dependent ubiquitination (30). We chose one such mutation, C53A/C56A, and compared its properties to the wild type. While the mutant bound EBNA3C similarly to the wild type, it did not stimulate EBNA3C ubiquitination (Fig. 7A). Further, the mutant protein functioned as a dominant negative when coexpressed with the wild-type protein, eliminating the ability of wild-type Roc1 to stimulate EBNA3C ubiquitination (Fig. 7A). While our previous mapping data had already strongly linked Roc1 binding to EBNA3C ubiquitination (Fig. 4C), this functional experiment unquestionably implicates a Roc1-dependent ligase in EBNA3C ubiquitination, most likely SCFSkp2.

FIG. 7.

Roc1 stimulates EBNA3C ubiquitination. (A) HEK 293T cells were transfected, as indicated, with expression plasmids for HA-tagged ubiquitin (Ub), myc-tagged EBNA3C (E3C) amino acids 1 to 365, and either HA-tagged Roc1 or a Roc1 mutant, C53A/C56A, which is deficient for ubiquitin recruitment. Cells were harvested at 36 h, and total protein was immunoprecipitated (IP) with myc-specific antibody. Samples were resolved by SDS-10% PAGE. Western blotting was done by stripping and reprobing the same membrane. (B) HEK 293T cells were transfected, as indicated, with expression plasmids for HA-tagged ubiquitin and HA-tagged Roc1. Cells were harvested at 36 h, and cell lysates were resolved by SDS-10% PAGE.

EBNA3C stimulates the ubiquitination of exogenously expressed p27 in human cells.

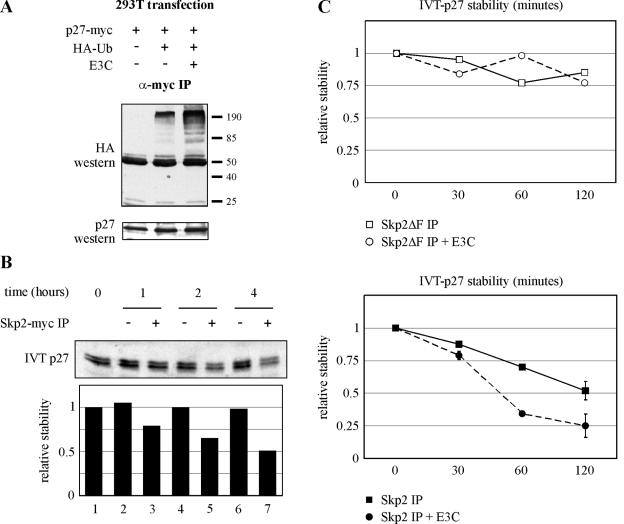

Having established that EBNA3C recruits SCFSkp2-associated ubiquitination activity, we tested whether p27 ubiquitination may be regulated by EBNA3C. HEK 293T cells were transfected with expression plasmids for myc-tagged p27, HA-tagged ubiquitin, and untagged EBNA3C. myc-specific immunoprecipitation resulted in the coimmunoprecipitation of ubiquitin-tagged p27 protein, an effect significantly and reproducibly enhanced with EBNA3C expression (Fig. 8A). This result implicates EBNA3C in upregulating the polyubiquitination of p27 in the context of this plasmid-based expression system.

FIG. 8.

EBNA3C stimulates p27 ubiquitination in HEK 293T cells and decreases p27 stability in an SCFSkp2-dependent degradation assay. (A) HEK 293T cells were transfected with expression plasmids for myc-tagged p27, HA-tagged ubiquitin (Ub), and untagged EBNA3C (E3C), as indicated. Cells were harvested at 36 h, and total protein was immunoprecipitated (IP) with myc-specific antibody (α-myc). Samples were resolved by SDS-10% PAGE. Western blotting was done by stripping and reprobing the same membrane. (B) HEK 293T cells were transfected with expression plasmids for myc-Skp2, Skp1, Cul1, Roc1, and Cks1 or, alternatively, with an equal amount of vector DNA. Cells were lysed at 36 h, and the SCFSkp2 complex was immunoprecipitated via the myc tag on Skp2. Immunoprecipitates were then incubated with 35S-labeled in vitro-translated (IVT) p27. Degradation reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C with samples taken for SDS-PAGE at the times indicated. Quantification of p27 autoradiography was done with ImageQuant software. All values were normalized to the zero time point. (C) In the upper panel, HEK 293T cells were transfected as described for panel B but with a Skp2 mutant with a deletion of the F-box (Skp2ΔF) replacing full-length Skp2. Cells were lysed at 36 h, and the SCFSkp2ΔF complex was immunoprecipitated via the myc tag on Skp2ΔF. Degradation assays were as described above with samples taken at the indicated times. In the sample represented by open circles, cells were additionally transfected with an untagged EBNA3C expression construct. In the lower panel, HEK 293T cells were transfected as described for panel B with immunoprecipitation for the myc tag on full-length Skp2. In the sample represented by filled circles, cells were additionally transfected with an untagged EBNA3C expression construct. +, with; −, without.

EBNA3C decreases p27 stability in an in vitro degradation assay.

Polyubiquitination of p27 in HEK 293T cells suggested that EBNA3C may be regulating p27 stability. To more directly assess the role of EBNA3C in this process, we employed an SCFSkp2-dependent in vitro degradation assay. HEK 293T cells were transfected with expression constructs for Skp1, Cul1, Roc1, Cks1, and myc-tagged Skp2. After 48 h, cells were lysed and the SCF complex was immunoprecipitated with monoclonal antibody against the myc tag. The complex was mixed with ATP, concentrated BJAB extract, and in vitro-translated p27. p27 stability was measured by collecting time points and resolving for autoradiography by SDS-PAGE. As shown in Fig. 8B, the SCF complex specifically resulted in time-dependent destabilization of in vitro-translated p27 (Fig. 8B, lanes 3, 5, and 7).

We next tested whether EBNA3C plays a role in regulating this complex. First, EBNA3C was expressed with SCF components Skp1, Cul1, Roc1, Cks1, and myc-tagged Skp2 deleted for the F-box domain. A similar Skp2 mutant has previously been demonstrated to function as a dominant negative for wild-type Skp2, as it dissociates substrate binding from ubiquitin recruitment (27). For both control and EBNA3C-expressing cells, p27 remained stable (Fig. 8C, upper panel). In contrast, when EBNA3C was expressed with the wild-type SCFSkp2 complex, reproducible enhancement of SCFSkp2 activity by EBNA3C was observed (Fig. 8C, lower panel). This result is consistent with EBNA3C regulating p27 stability by directly targeting specific components of the SCFSkp2 complex, in particular Skp2 and Roc1.

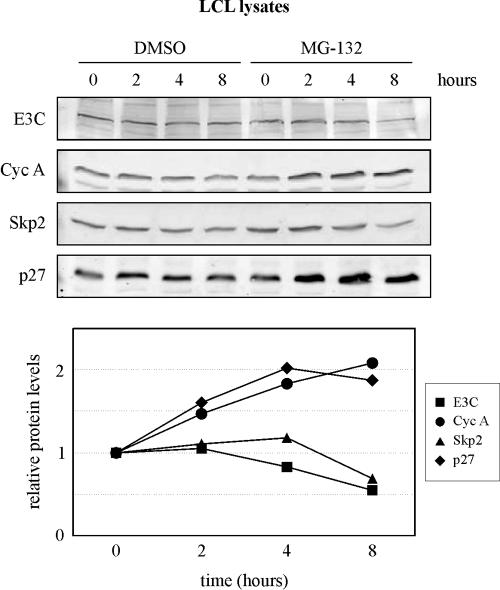

p27 is stabilized in LCLs by treatment with the proteasome inhibitor MG-132.

The aforementioned data strongly indicate that EBNA3C can stimulate p27 ubiquitination in cells and enhance p27 degradation in an SCFSkp2-dependent in vitro assay. While we did not regularly see a reduction in p27 levels with EBNA3C expression in our plasmid-driven system, a previous study detected a dramatic decrease in endogenous p27 levels with EBNA3C expression in a drug-inducible system (33). It should also be noted that, in our plasmid-driven system, we routinely detected the ubiquitination of both Skp2 and EBNA3C (Fig. 2 to 4). While our in vitro degradation assay and the work of Parker and colleagues (33) strongly support a link between p27 ubiquitination and degradation, it is less clear whether Skp2 and EBNA3C may be similarly regulated. We therefore decided to test the ability of a proteasome inhibitor, MG-132, to stabilize these proteins in asynchronously growing LCLs, an indication of whether these molecules are being significantly directed into the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway in the context of EBV latent infection. A representative experiment is shown in the upper panel of Fig. 9. Interestingly, while p27 and another molecule, cyclin A, were stabilized by 2 h of MG-132 treatment, neither Skp2 nor EBNA3C was stabilized over an 8-h treatment (Fig. 9, bottom panel). This suggests that either Skp2 and EBNA3C are not significantly ubiquitinated in LCLs (as they are in our plasmid-based system) or that there is a disconnect between their ubiquitination and degradation in LCLs. So, while the ubiquitination of EBNA3C in our plasmid-based system provided a convenient and powerful mechanism for mapping the recruitment of this activity, it is not yet clear that ubiquitination activity is an important regulator of the EBNA3C protein itself in cells.

FIG. 9.

p27, but neither Skp2 nor EBNA3C (E3C), is stabilized in LCLs by treatment with the proteasome inhibitor MG-132. Asynchronously growing LCLs were treated for 8 h with either 10 μg of MG-132/ml or DMSO (control). Cells were harvested at the times indicated. Lysates were normalized by the Bradford assay and resolved by SDS-10% PAGE. Western blotting was done by stripping and reprobing the same membrane. Bands were quantified, and the data for each time point were plotted in the line graph as MG-132 band intensity divided by DMSO band intensity. Cyc A, cyclin A.

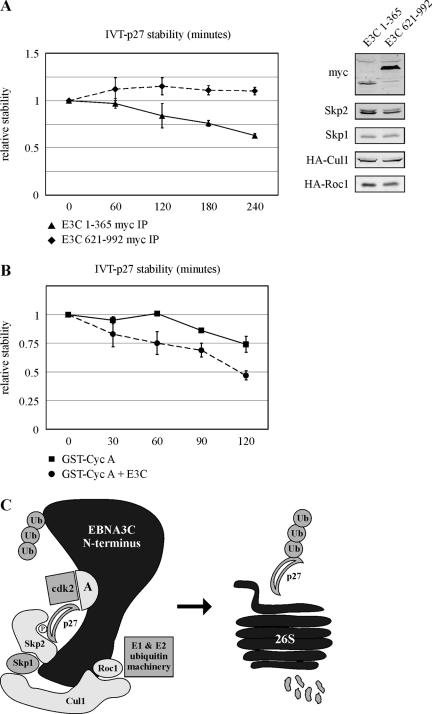

EBNA3C recruits p27 degradation activity to cyclin A complexes.

As EBNA3C apparently directly binds SCFSkp2 components and as EBNA3C regulates p27 ubiquitination and stability, an attractive hypothesis is that EBNA3C may provide a physical link between p27 and SCFSkp2, thereby facilitating and enhancing Skp2 recognition of the substrate. We and others have failed to identify a molecular association between EBNA3C and p27 either in vitro or in cells. Therefore, we hypothesized that cyclin A, which also strongly binds the amino terminus of EBNA3C (21), may serve as an intermediary molecule, in addition to EBNA3C, functionally linking p27 to the SCFSkp2 complex.

To definitely confirm that the amino terminus of EBNA3C associates not only with the SCFSkp2 complex but also with p27 degradation activity in cells, HEK 293T cells were transfected with expression constructs encoding either the amino terminus of EBNA3C, amino acids 1 to 365, or the carboxy terminus, amino acids 621 to 992 (Fig. 10A, right panel). Both proteins are myc-tagged. Cells were additionally transfected with expression constructs for components of the SCFSkp2 complex (Fig. 10A, right panel). Samples were immunoprecipitated with myc-specific antibody and incubated with in vitro-translated p27 as for the degradation assays above. While p27 was stable in the presence of the EBNA3C carboxy terminus (Fig. 10A, left panel), incubation with the amino terminus resulted in significant and reproducible degradation of p27 over a 4-h incubation period (Fig. 10A, left panel). This result confirms the association between the EBNA3C amino terminus and p27 degradation activity and is consistent with a model whereby EBNA3C facilitates the assembly of cyclin A/SCFSkp2 complexes which potentially stimulates p27 degradation in cells.

FIG. 10.

EBNA3C recruits ubiquitination activity to cyclin A complexes. (A) HEK 293T cells were transfected with Skp2, Skp1, Cul1, Roc1, and Cks1 expression plasmids. Cells were additionally transfected with expression plasmids for EBNA3C (E3C) amino acids 1 to 365 or EBNA3C amino acids 621 to 992, both tagged with the myc epitope. Cells were lysed at 36 h, immunoprecipitated (IP) with myc-specific antibody, and incubated with 35S-labeled in vitro-translated (IVT) p27. Degradation reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C, with samples taken for SDS-PAGE at the times indicated. Quantification of p27 autoradiography was done with ImageQuant software. All values were normalized to the zero time point. The right panel confirms protein expression in cell lysates. (B) HEK 293T cells were transfected with Skp2, Skp1, Cul1, Roc1, and Cks1 expression plasmids. Cells were additionally transfected with either vector (squares) or EBNA3C (circles). Cells were lysed at 36 h and incubated with GST-cyclin A (Cyc A) fusion protein purified from bacteria and prebound to glutathione-Sepharose beads. GST-cyclin A precipitates were then incubated with 35S-labeled in vitro-translated p27. Degradation reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C, with samples taken for SDS-PAGE at the times indicated. Quantification of p27 autoradiography was done with ImageQuant software. All values were normalized to the zero time point. (C) This model suggests that the amino terminus of EBNA3C may serve as scaffolding for the assembly of cyclin A/cdk2/p27 with SCFSkp2. This may facilitate p27 ubiquitination and, ultimately, degradation by the 26S proteasome.

To further test this model, cyclin A complexes were precipitated from HEK 293T cells either in the presence or in the absence of EBNA3C. Complexes were then incubated with in vitro-translated p27 and other degradation reaction components as described in above experiments. Previously, we demonstrated that, without the addition of exogenous SCFSkp2, in vitro-translated p27 is stable over the course of a 2-h degradation reaction. However, if cyclin A complexes are precipitated from HEK 293T lysates with a GST-cyclin A fusion protein bound to glutathione-Sepharose beads, the degradation of p27 increases by approximately 25% after 2 h (Fig. 10B). Importantly, expression of EBNA3C in HEK 293T cells resulted in enhancement of p27 degradation with greater than 50% degraded by 2 h (Fig. 10B). This result is consistent with cyclin A complexes mediating p27-specific degradation activity in HEK 293T cells, an effect that is significantly enhanced by EBNA3C expression in this system. This result is also consistent with EBNA3C stabilizing the association between cyclin A and SCFSkp2 complexes, which may result in p27 being targeted for degradation specifically at the level of cyclin A complexes (Fig. 10C).

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have demonstrated that EBNA3C targets cell cycle regulators, resulting in deregulation of the mammalian cell cycle (3, 20, 21, 32, 33). EBNA3C manipulates the Rb-E2F axis in reporter assays and in rat fibroblast transformation experiments (32). Additionally, EBNA3C causes the accumulation of cells in S/G2 and prevents the induction of certain mitotic checkpoints, resulting in aberrant nuclear division (33). We have previously shown that EBNA3C specifically targets cyclin A complexes and stimulates cyclin A-dependent kinase activity (20, 21). Here, we propose a mechanism for this stimulation, namely the recruitment of the SCFSkp2 complex to cyclin A, where the kinase inhibitor p27 is targeted for degradation (Fig. 10C).

Our studies began with the observation that mutations at the carboxy terminus of p27, which remove the regulatory amino acid threonine-187, eliminate the ability of EBNA3C to rescue p27-dependent suppression of cyclin A kinase activity. Threonine-187 is known to be a critical regulator of p27 stability. Phosphorylation of this residue enhances the interaction of p27 with the E3 ubiquitin ligase complex SCFSkp2, directing p27 for degradation via the ubiquitin/proteasome system (29, 43). We therefore investigated whether EBNA3C plays a role in regulating p27 stability and whether this regulation contributes to the stimulation of cyclin A-dependent kinase activity by EBNA3C. We first demonstrated that EBNA3C strongly associates with ubiquitination activity in cells and is, in fact, itself ubiquitinated in our plasmid-driven system. Further, we found significant molecular links between EBNA3C and the SCFSkp2 core components Skp2 and Roc1. EBNA3C coimmunoprecipitates with Skp2 from LCL lysates and strongly colocalizes with Skp2 in HeLa cell nuclei. The interaction with Roc1 was perhaps even more fundamental to the ubiquitination phenotypes we observed. EBNA3C strongly binds Roc1 in vitro and in cells, with the amino terminus of Roc1 essential for the interaction; this is a potentially important observation, as it suggests that the carboxy-terminal RING finger motif is likely free to recruit E2 ubiquitin conjugation machinery, even when EBNA3C is bound. Indeed, point mutations in the RING finger domain, while having no effect on EBNA3C binding, eliminate the recruitment of ubiquitination activity to EBNA3C. We also, importantly, found that both EBNA3C ubiquitination and Roc1 binding map to the same 10-amino-acid region at the amino terminus of EBNA3C, strengthening our assertion that EBNA3C is not just coincidentally recruiting SCFSkp2 components but is actually assembling active ubiquitin ligase complexes.

Having demonstrated that EBNA3C associates with active SCFSkp2 complexes, we asked whether this association is important in the regulation of p27 stability. EBNA3C specifically stimulates the ubiquitination of p27 when both molecules are expressed in HEK 293T cells and destabilizes p27 in an in vitro degradation assay based on SCFSkp2 complexes immunoprecipitated from HEK 293T cells. These data are consistent with the work of others showing that endogenous p27 steady-state levels are dramatically reduced in the presence of EBNA3C (33). As SCFSkp2 and cyclin A both bind a small and conserved amino-terminal region of EBNA3C (amino acids 130 to 159), and as the regulation of p27 stability potentially plays a critical role in cyclin A-dependent kinase activity, we decided to test whether EBNA3C recruits p27 degradation activity to cyclin A kinase complexes. This question was especially interesting in the context of previous data suggesting that cyclin A and SCFSkp2form complexes in transformed but not primary cells (45). It has been hypothesized that cyclin A/cdk2 may function in these complexes to regulate the phosphorylation state of potential SCFSkp2 substrates, thereby increasing the association of these substrates with the F-box protein Skp2. However, a largely unexplored hypothesis is whether SCFSkp2 may regulate the stability of substrates like p27 that enter complex with cyclin A. In support of this second hypothesis, we show that in HEK 293T cells, p27 degradation activity is normally associated with cyclin A complexes, an association that is enhanced with EBNA3C expression (Fig. 10C).

While a recent report suggests that the papillomavirus protein E7 may be ubiquitinated by a Skp2- and Cul1-containing E3 ligase (29a), no viral molecule has previously been shown to regulate p27 stability through the SCFSkp2 complex. However, it has been demonstrated recently that adenovirus E1B-55K protein forms a complex with components of the VHL E3 ubiquitin ligase, including Cul2, elongin B, and elongin C (35). This complex is structurally and functionally homologous to SCFSkp2 and may regulate p53 stability in virally infected cells. Similarly, EBNA3C may serve as a bridge between p27 and SCFSkp2; however, in contrast to the E1B-55K association with p53, the association of p27 with EBNA3C may be tethered by another component of the complex which includes cyclin A. While EBNA3C weakly coimmunoprecipitates with p27 in cells, in vitro binding experiments with either bacterially expressed or in vitro-translated proteins have failed to demonstrate a direct interaction, although we cannot eliminate the possibility that some modification of p27 may be necessary for EBNA3C binding. Based on the results in this report, we presently favor the hypothesis that additional intermediary molecules, such as cyclin A, are necessary for EBNA3C-mediated recruitment of p27 to SCFSkp2 complexes and that perhaps only specific populations of p27 are targeted for degradation by EBNA3C. In summary, we have demonstrated that EBNA3C binds and regulates the SCFSkp2 E3 ligase complex. As SCFSkp2 is commonly deregulated in human cancers, this and future studies of the essential EBV antigen EBNA3C will potentially clarify the role of SCFSkp2 in EBV-mediated tumor development and provide new possibilities for therapeutic development.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stephen Elledge, Ed Harlow, Philip Hinds, Elliot Kieff, Maria Mudryj, Michele Pagano, Martin Rowe, George Mosialos, and Yue Xiong for generously providing reagents.

J.S.K. is supported by the Lady Tata Memorial Trust. The project is supported by NIH grants NCI CA72150-07, NCI CA91792-01, and DCR DE14136-01 to E.S.R. E.S.R. is a scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society of America.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aiello, L., R. Guilfoyle, K. Huebner, and R. Weinmann. 1979. Adenovirus 5 DNA sequences present and RNA sequences transcribed in transformed human embryo kidney cells (HEK-Ad-5 or 293). Virology 94:460-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allday, M. J., D. H. Crawford, and J. A. Thomas. 1993. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) nuclear antigen 6 induces expression of the EBV latent membrane protein and an activated phenotype in Raji cells. J. Gen. Virol. 74:361-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allday, M. J., and P. J. Farrell. 1994. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen EBNA3C/6 expression maintains the level of latent membrane protein 1 in G1-arrested cells. J. Virol. 68:3491-3498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aster, J. C., E. S. Robertson, R. P. Hasserjian, J. R. Turner, E. Kieff, and J. Sklar. 1997. Oncogenic forms of NOTCH1 lacking either the primary binding site for RBP-Jkappa or nuclear localization sequences retain the ability to associate with RBP-Jkappa and activate transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 272:11336-11343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bai, C., P. Sen, K. Hofmann, L. Ma, M. Goebl, J. W. Harper, and S. J. Elledge. 1996. SKP1 connects cell cycle regulators to the ubiquitin proteolysis machinery through a novel motif, the F-box. Cell 86:263-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carrano, A. C., E. Eytan, A. Hershko, and M. Pagano. 1999. SKP2 is required for ubiquitin-mediated degradation of the CDK inhibitor p27. Nat. Cell Biol. 1:193-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiarle, R., Y. Fan, R. Piva, H. Boggino, J. Skolnik, D. Novero, G. Palestro, C. De Wolf-Peeters, M. Chilosi, M. Pagano, and G. Inghirami. 2002. S-phase kinase-associated protein 2 expression in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma inversely correlates with p27 expression and defines cells in S phase. Am. J. Pathol. 160:1457-1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen, J. I., F. Wang, J. Mannick, and E. Kieff. 1989. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 2 is a key determinant of lymphocyte transformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:9558-9562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cotter, M. A., II, and E. S. Robertson. 2000. Modulation of histone acetyltransferase activity through interaction of Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 3C with prothymosin alpha. Mol. Cell. Biol 20:5722-5735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devoto, S. H., M. Mudryj, J. Pines, T. Hunter, and J. R. Nevins. 1992. A cyclin A-protein kinase complex possesses sequence-specific DNA binding activity: p33cdk2 is a component of the E2F-cyclin A complex. Cell 68:167-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganoth, D., G. Bornstein, T. K. Ko, B. Larsen, M. Tyers, M. Pagano, and A. Hershko. 2001. The cell-cycle regulatory protein Cks1 is required for SCF(Skp2)-mediated ubiquitinylation of p27. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:321-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia, J. F., F. I. Camacho, M. Morente, M. Fraga, C. Montalban, T. Alvaro, C. Bellas, A. Castano, A. Diez, T. Flores, C. Martin, M. A. Martinez, F. Mazorra, J. Menarguez, M. J. Mestre, M. Mollejo, A. I. Saez, L. Sanchez, and M. A. Piris. 2003. Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells harbor alterations in the major tumor suppressor pathways and cell-cycle checkpoints: analyses using tissue microarrays. Blood 101:681-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammerschmidt, W., and B. Sugden. 1989. Genetic analysis of immortalizing functions of Epstein-Barr virus in human B lymphocytes. Nature 340:393-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinds, P. W., S. Mittnacht, V. Dulic, A. Arnold, S. I. Reed, and R. A. Weinberg. 1992. Regulation of retinoblastoma protein functions by ectopic expression of human cyclins. Cell 70:993-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamura, T., D. M. Koepp, M. N. Conrad, D. Skowyra, R. J. Moreland, O. Iliopoulos, W. S. Lane, W. G. Kaelin, Jr., S. J. Elledge, R. C. Conaway, J. W. Harper, and J. W. Conaway. 1999. Rbx1, a component of the VHL tumor suppressor complex and SCF ubiquitin ligase. Science 284:657-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaye, K. M., K. M. Izumi, and E. Kieff. 1993. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 is essential for B-lymphocyte growth transformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:9150-9154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kieff, E., and A. B. Rickinson. 2002. Epstein-Barr virus and its replication, p. 2511-2573. In D. Knipe and P. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed., vol. 2. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim, S. Y., A. Herbst, K. A. Tworkowski, S. E. Salghetti, and W. P. Tansey. 2003. Skp2 regulates Myc protein stability and activity. Mol. Cell 11:1177-1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knight, J. S., K. Lan, C. Subramanian, and E. S. Robertson. 2003. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 3C recruits histone deacetylase activity and associates with the corepressors mSin3A and NCoR in human B-cell lines. J. Virol. 77:4261-4272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knight, J. S., and E. S. Robertson. 2004. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 3C regulates cyclin A/p27 complexes and enhances cyclin A-dependent kinase activity. J. Virol. 78:1981-1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knight, J. S., N. Sharma, D. E. Kalman, and E. S. Robertson. 2004. A cyclin-binding motif within the amino-terminal homology domain of EBNA3C binds cyclin A and modulates cyclin A-dependent kinase activity in Epstein-Barr virus-infected cells. J. Virol. 78:12857-12867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Latres, E., R. Chiarle, B. A. Schulman, N. P. Pavletich, A. Pellicer, G. Inghirami, and M. Pagano. 2001. Role of the F-box protein Skp2 in lymphomagenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:2515-2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim, M. S., A. Adamson, Z. Lin, B. Perez-Ordonez, R. C. Jordan, S. Tripp, S. L. Perkins, and K. S. Elenitoba-Johnson. 2002. Expression of Skp2, a p27(Kip1) ubiquitin ligase, in malignant lymphoma: correlation with p27(Kip1) and proliferation index. Blood 100:2950-2956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lyapina, S. A., C. C. Correll, E. T. Kipreos, and R. J. Deshaies. 1998. Human CUL1 forms an evolutionarily conserved ubiquitin ligase complex (SCF) with SKP1 and an F-box protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:7451-7456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mannick, J. B., J. I. Cohen, M. Birkenbach, A. Marchini, and E. Kieff. 1991. The Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein encoded by the leader of the EBNA RNAs is important in B-lymphocyte transformation. J. Virol. 65:6826-6837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marti, A., C. Wirbelauer, M. Scheffner, and W. Krek. 1999. Interaction between ubiquitin-protein ligase SCFSKP2 and E2F-1 underlies the regulation of E2F-1 degradation. Nat. Cell Biol. 1:14-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendez, J., X. H. Zou-Yang, S. Y. Kim, M. Hidaka, W. P. Tansey, and B. Stillman. 2002. Human origin recognition complex large subunit is degraded by ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis after initiation of DNA replication. Mol. Cell 9:481-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michel, J. J., and Y. Xiong. 1998. Human CUL-1, but not other cullin family members, selectively interacts with SKP1 to form a complex with SKP2 and cyclin A. Cell Growth Differ. 9:435-449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montagnoli, A., F. Fiore, E. Eytan, A. C. Carrano, G. F. Draetta, A. Hershko, and M. Pagano. 1999. Ubiquitination of p27 is regulated by Cdk-dependent phosphorylation and trimeric complex formation. Genes Dev. 13:1181-1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29a.Oh, K.-J., A. Kalinina, J. Wang, K. Nakayama, K. I. Nakayama, and S. Bagchi. 2004. The papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein is ubiquitinated by UbcH7 and Cullin 1- and Skp2-containing E3 ligase. J. Virol. 78:5338-5346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohta, T., J. J. Michel, A. J. Schottelius, and Y. Xiong. 1999. ROC1, a homolog of APC11, represents a family of cullin partners with an associated ubiquitin ligase activity. Mol. Cell 3:535-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pagano, M., S. W. Tam, A. M. Theodoras, P. Beer-Romero, G. Del Sal, V. Chau, P. R. Yew, G. F. Draetta, and M. Rolfe. 1995. Role of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in regulating abundance of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27. Science 269:682-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parker, G. A., T. Crook, M. Bain, E. A. Sara, P. J. Farrell, and M. J. Allday. 1996. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen (EBNA) 3C is an immortalizing oncoprotein with similar properties to adenovirus E1A and papillomavirus E7. Oncogene 13:2541-2549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parker, G. A., R. Touitou, and M. J. Allday. 2000. Epstein-Barr virus EBNA3C can disrupt multiple cell cycle checkpoints and induce nuclear division divorced from cytokinesis. Oncogene 19:700-709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ponten, J., and E. Saksela. 1967. Two established in vitro cell lines from human mesenchymal tumours. Int. J. Cancer 2:434-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Querido, E., P. Blanchette, Q. Yan, T. Kamura, M. Morrison, D. Boivin, W. G. Kaelin, R. C. Conaway, J. W. Conaway, and P. E. Branton. 2001. Degradation of p53 by adenovirus E4orf6 and E1B55K proteins occurs via a novel mechanism involving a Cullin-containing complex. Genes Dev. 15:3104-3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Radkov, S. A., R. Touitou, A. Brehm, M. Rowe, M. West, T. Kouzarides, and M. J. Allday. 1999. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 3C interacts with histone deacetylase to repress transcription. J. Virol. 73:5688-5697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rickinson, A. B., and E. Kieff. 2002. Epstein-Barr virus, p. 2575-2627. In D. Knipe and P. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, vol. 2. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robertson, E. S. 1997. The Epstein-Barr virus EBNA3 protein family as regulators of transcription. Epstein Barr Virus Rep. 4:143-150. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seki, R., T. Okamura, H. Koga, K. Yakushiji, M. Hashiguchi, K. Yoshimoto, H. Ogata, R. Imamura, Y. Nakashima, M. Kage, T. Ueno, and M. Sata. 2003. Prognostic significance of the F-box protein Skp2 expression in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am. J. Hematol. 73:230-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Subramanian, C., S. Hasan, M. Rowe, M. Hottiger, R. Orre, and E. S. Robertson. 2002. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 3C and prothymosin alpha interact with the p300 transcriptional coactivator at the CH1 and CH3/HAT domains and cooperate in regulation of transcription and histone acetylation. J. Virol. 76:4699-4708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tomkinson, B., E. Robertson, and E. Kieff. 1993. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear proteins EBNA-3A and EBNA-3C are essential for B-lymphocyte growth transformation. J. Virol. 67:2014-2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trompouki, E., E. Hatzivassiliou, T. Tsichritzis, H. Farmer, A. Ashworth, and G. Mosialos. 2003. CYLD is a deubiquitinating enzyme that negatively regulates NF-kappaB activation by TNFR family members. Nature 424:793-796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsvetkov, L. M., K. H. Yeh, S. J. Lee, H. Sun, and H. Zhang. 1999. p27(Kip1) ubiquitination and degradation is regulated by the SCF(Skp2) complex through phosphorylated Thr187 in p27. Curr. Biol. 9:661-664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.von der Lehr, N., S. Johansson, S. Wu, F. Bahram, A. Castell, C. Cetinkaya, P. Hydbring, I. Weidung, K. Nakayama, K. I. Nakayama, O. Soderberg, T. K. Kerppola, and L. G. Larsson. 2003. The F-box protein Skp2 participates in c-Myc proteosomal degradation and acts as a cofactor for c-Myc-regulated transcription. Mol. Cell 11:1189-1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang, H., R. Kobayashi, K. Galaktionov, and D. Beach. 1995. p19Skp1 and p45Skp2 are essential elements of the cyclin A-CDK2 S phase kinase. Cell 82:915-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao, B., and C. E. Sample. 2000. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 3C activates the latent membrane protein 1 promoter in the presence of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 through sequences encompassing an Spi-1/Spi-B binding site. J. Virol. 74:5151-5160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zheng, N., B. A. Schulman, L. Song, J. J. Miller, P. D. Jeffrey, P. Wang, C. Chu, D. M. Koepp, S. J. Elledge, M. Pagano, R. C. Conaway, J. W. Conaway, J. W. Harper, and N. P. Pavletich. 2002. Structure of the Cul1-Rbx1-Skp1-F boxSkp2 SCF ubiquitin ligase complex. Nature 416:703-709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou, P., and P. M. Howley. 1998. Ubiquitination and degradation of the substrate recognition subunits of SCF ubiquitin-protein ligases. Mol. Cell 2:571-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]