Abstract

Background

Owing to the global health workforce crisis, more funding has been invested in strengthening human resources for health, particularly for HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria control; however, little is known about how these investments in training are evaluated. This paper examines how frequently HIV, malaria, and TB healthcare provider training programs have been scientifically evaluated, synthesizes information on the methods and outcome indicators used, and identifies evidence gaps for future evaluations to address.

Methods

We conducted a systematic scoping review of publications evaluating postgraduate training programs, including in-service training programs, for HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria healthcare providers between 2000 and 2016. Using broad inclusion criteria, we searched three electronic databases and additional gray literature sources. After independent screening by two authors, data about the year, location, methodology, and outcomes assessed was extracted from eligible training program evaluation studies. Training outcomes evaluated were categorized into four levels (reaction, learning, behavior, and results) based on the Kirkpatrick model.

Findings

Of 1473 unique publications identified, 87 were eligible for inclusion in the analysis. The number of published articles increased after 2006, with most (n = 57, 66%) conducted in African countries. The majority of training evaluations (n = 44, 51%) were based on HIV with fewer studies focused on malaria (n = 28, 32%) and TB (n = 23, 26%) related training. We found that quantitative survey of trainees was the most commonly used evaluation method (n = 29, 33%) and the most commonly assessed outcomes were knowledge acquisition (learning) of trainees (n = 44, 51%) and organizational impacts of the training programs (38, 44%). Behavior change and trainees’ reaction to the training were evaluated less frequently and using less robust methods; costs of training were also rarely assessed.

Conclusions

Our study found that a limited number of robust evaluations had been conducted since 2000, even though the number of training programs has increased over this period to address the human resource shortage for HIV, malaria, and TB control. Specifically, we identified a lack evaluation studies on TB- and malaria-related healthcare provider training and very few studies assessing behavior change of trainees or costs of training. Developing frameworks and standardized evaluation methods may facilitate strengthening of the evidence base to inform policies on and investments in training programs.

Keywords: Scoping review, Training evaluation, Evaluation methods, Tuberculosis, HIV, Malaria

Background

It is becoming increasingly evident that strong human resources for health (HRH) are essential to improve global health, with recent studies showing that health outcomes are strongly correlated with the quality and density of healthcare providers (HCPs) [1, 2]. Despite remarkable increases in financial support to disease-specific prevention and control programs [3, 4], inadequate HRH is still a major impediment in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where diseases such as HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis (TB) cause substantial mortality, morbidity, and negative economic impact [1, 5, 6]. In addition to a shortage in the number of HCPs in LMICs [7], lack of training to improve capacity of staff at different service levels, inadequate geographical distribution within countries, dissatisfaction with remuneration, and low motivation along with poor staff retention contribute to the inconsistent and inadequate quality of services provided by HCPs [8]. As a result of the global health workforce crisis, more funding has been invested in strengthening HRH since 2000. Within HIV, malaria, and TB control programs, training of HCPs has been an area of focus [9]. Between 2002 and 2010, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria (the Global Fund)—the largest non-governmental funder of human resources—invested US$1.3 billion for human resource development activities, and it is estimated that more than half of this budget was invested in disease-focused training activities [9]. As a result of increasing attention and investment in strengthening HRH in HIV, malaria and TB control programs, in 2014, the Global Fund provided 16 million person-episodes of training for HCPs, which was a tenfold increase compared to the number trained in 2005 [10].

Along with this investment comes a need for evaluations to provide information for international funders and national program managers to determine if a program should continue, improve, end, or scale up, in order to ensure that resources are allocated effectively and efficiently [11]. However, we found no studies that systematically reviewed existing literature on evaluations of HCP training programs. Furthermore, there is no consensus on best practice in terms of evaluation methods applied and outcome indicators assessed; therefore, summarizing existing literature on evaluations of HCP training is essential.

Among all the frameworks or conceptual models developed to guide conduct of training evaluations, the first and most commonly referenced framework to date is the Kirkpatrick model [12–15]. The Kirkpatrick model has been used in the design of training evaluations in business and industry in the 1960s. It forms the basis of various theories in training evaluation and has had a profound impact on other evaluation models developed subsequently [13, 16–18]. The Kirkpatrick model identifies four levels of training outcomes that can be evaluated: reaction, learning, behavior, and results [19]. The reaction level assesses how well trainees appreciated a particular training program. In practice, evaluators measure trainees’ affective response to the quality and the relevance of the training program when assessing reaction [12]. The learning level assesses how well trainees have acquired intended knowledge, skills, or attitudes based on participation in the learning event. It is usually measured in the form of tests [13]. The behavior level addresses the extent to which knowledge and skills gained in training are applied on the job. Lastly, for the results level, evaluators try to capture the impact that training has had at an organizational level; this includes changes in health outcomes [12].

In light of the growing focus on and investment in improving human resource capacity for HIV, malaria, and TB control and the need for evaluations of these investments, we conducted a systematic review to investigate how frequently HIV, malaria, and TB HCP training programs have been scientifically evaluated, synthesize information on the methods and outcome indicators used, and identify areas for improvement in current training evaluation approaches.

Methods

This review was based on the systematic scoping review methodological framework designed by Arksey and O’Malley [20]. The following key steps were included when we conducted the review: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results.

Stage 1: identifying research question

The population for this review was HCPs delivering health services related to HIV, TB, or malaria. We included doctors, nurses, healthcare workers, lay health workers, traditional health practitioners, and laboratory technicians in our definition of HCPs. Teachers and other professionals delivering health services outside their routine work were not considered HCPs. The intervention of interest was any training or capacity building activity related to health service delivery. As the purpose of this study is to identify the methods and outcomes used for training evaluations, the study design and outcomes of the included studies were left intentionally broad, and a meta-analysis was not appropriate at this stage.

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

We conducted a search on articles published after January 1, 2000, in three electronic databases on April 28, 2016: PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library. In addition, we searched for relevant gray literature in Google Scholar (first 100 citations) and on six major non-government organizations’ (NGOs) websites on July 18, 2016: WHO, Oxfam International, Save the Children, Community Health Workers Central (CHW Central), UNAIDS, and Target TB, UK. The search terms used are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search strategy

| Database | Search terms in title or abstract | No. of papers retrieved |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (healthcare workers OR healthcare providers OR healthcare professionals OR healthcare staff OR healthcare practitioners OR health workers OR health providers OR health professionals OR health staff OR health practitioners OR health-care workers OR health-care providers OR health-care professionals OR health-care staff OR health-care practitioners) | 131,755 |

| AND (training OR continuing professional development OR continuing medical education) | 16,588 | |

| AND (evaluat* OR assess*) | 7518 | |

| AND (tuberculosis OR TB OR HIV OR malaria OR AIDS) | 707 | |

| Limit to articles published from January 1, 2000, to April 28, 2016 | 525 | |

| EMBASE | (healthcare workers OR healthcare providers OR healthcare professionals OR healthcare staff OR healthcare practitioners OR health workers OR health providers OR health professionals OR health staff or health practitioners OR health-care workers OR health-care professionals OR health-care providers OR health-care practitioners OR health-care staff) | 166,542 |

| AND (training OR continuing professional development OR continuing medical education) | 21,847 | |

| AND (evaluat* OR assess*) | 10,544 | |

| AND (malaria OR AIDS OR HIV OR tuberculosis OR TB) | 927 | |

| Limit to publication year from 2000 to 2016 | 806 | |

| Cochrane Library | (healthcare workers OR healthcare providers OR healthcare professionals OR healthcare staff OR healthcare practitioners OR health workers OR health providers OR health professionals OR health staff or health practitioners OR health-care workers OR health-care professionals OR health-care providers OR health-care practitioners OR health-care staff) | 21,999 |

| AND (training OR continuing professional development OR continuing medical education) | 4984 | |

| AND (evaluat* OR asses*) | 3837 | |

| AND (malaria OR AIDS OR HIV OR tuberculosis OR TB) | 314 | |

| Limit to publication year from 2000 to 2016 | 249 |

Stage 3: study selection

All citations were imported into EndNote X7 and duplicate citations were removed manually. A two-stage screening process for eligibility was conducted. Articles were eligible for inclusion if the studies met the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2). In the first stage of screening, two researchers independently reviewed titles and abstract of the citations. Results from both researchers were compared, and titles for which an abstract was not available or for which either of the reviewers’ suggested inclusion were put forward for subsequent full-text review as part of the second stage of eligibility screening. If the studies did not meet the eligibility criteria, they were excluded at this stage. Articles that could not be obtained through online databases and library searches at the National University of Singapore and London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine were also excluded from final analysis.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | • Study describes evaluations of HIV, malaria, or TB HCP post-graduate training programs • Study contains descriptions of the training program, methods used to evaluate the program and outcomes assessed in the evaluation. • Study was published after January 1, 2000. • Geographic areas of studies are not restricted. • Only published articles will be included. |

| Exclusion criteria | • Literature reviews with no primary data collection • Study describes framework or methodology proposed for training evaluation without primary data collection and analysis. |

Stage 4: extracting and analyzing the data

We extracted relevant information from articles included in the final analysis using a pre-designed standardized excel sheet. Table 3 summarizes data extracted and definitions used for categorizing data. For each study, we categorized the training outcomes evaluated into four levels (reaction, learning, behavior, and results) based on the Kirkpatrick model.

Table 3.

Definitions of extracted data

| Data extracted | Definition |

|---|---|

| Year of publication | Year in which the study was published |

| Study location | Country in which the study took place |

| Disease area | The disease area that the training program aimed to target (HIV, malaria, or tuberculosis). |

| Evaluation methods | |

| Pre- and post-training tests | Trainees were given tests on their knowledge acquisition before and after training sessions. Scores of both tests were compared. |

| Quantitative survey of trainees | Trainees’ feedback, demographic information, or other key information used for evaluation were collected using questionnaires filled out by either trainees or evaluators via one-to-one interviews. Data was analyzed using quantitative methods. |

| Qualitative interviews | Trainees were interviewed one-to-one by evaluators after training. Information was collected through in-depth or semi-structured interviews. Data was analyzed using qualitative methods. |

| Review patient records | Patient records were extracted and patient level outcomes were compared before and after the training program or between intervention and control groups. Data sources included medical records at health facilities, patient cards, or local surveillance data. |

| Patient exit survey | After training programs, patients were surveyed by evaluators after consultations with trainees. A standardized questionnaire was used to record the services received by patients, drugs prescribed, or whether they were satisfied with the consultations. |

| Observation | Trainees’ on-the-job performance was directly observed at their work place and assessed by evaluators or their supervisors. |

| Standardized patient | Standardized patients refer to people trained to accurately portray a specific medical condition. In this method, trainees’ performance was evaluated during clinical encounters without the presence of evaluators. |

| Focus group discussion | Trainees were gathered in groups after training programs to discuss their experiences, feedback, and reflections on the training programs. The discussion was usually guided by a facilitator. |

| Cost-effective analysis | The cost of the training program was calculated and compared with the outcomes of the program. |

| Outcomes evaluated | |

| Reaction | How trainees react to the training and their perceived value of the training |

| Learning | To what degree trainees acquire intended knowledge, skills, and attitudes based on participation in the learning event |

| Behavior | To what degree trainees apply what they learned during training sessions on their job |

| Results | The downstream organizational outcomes/impacts that occur as a result of the training |

Stage 5: collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

Guided by the research question, we summarized the results on characteristics of the included studies using descriptive statistics.

Results

Summary of included studies

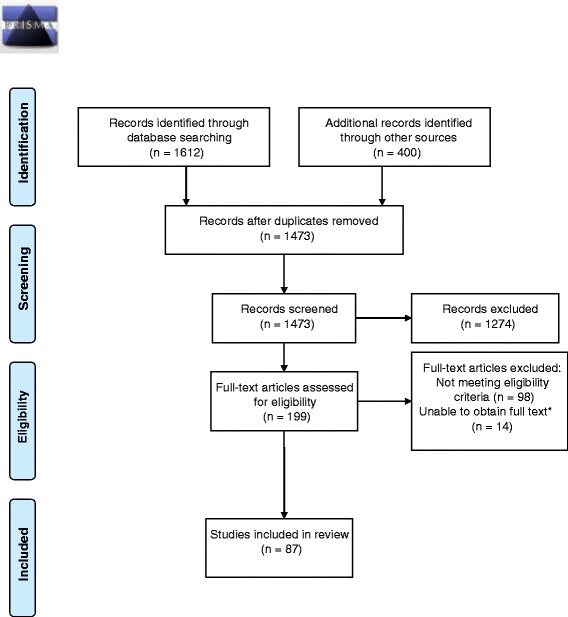

We retrieved a total of 1612 citations from the three databases and 400 from the gray literature search. After removing duplicates, we screened titles and abstracts of 1473 unique publications, of which 199 went through to the full-text assessment and 87 met our inclusion criteria for inclusion in the analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of literature search and screening. *Full text not available through National University of Singapore and London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

We found that the number of published articles on HCP training evaluation has increased, particularly after 2006 (Table 4). In terms of geographic distribution of studies, most (n = 57, 66%) took place in African countries. Compared to the number of studies in Africa, only 16 (18%) evaluation studies took place in Asian countries, and even fewer were conducted in North America (n = 10, 11%), Europe (n = 2, 2%), and South America (n = 2, 2%). The majority of training evaluations—44 studies (51%)—were based on HCPs providing HIV-related health services. Fewer studies were focused on HCPs providing malaria (n = 28, 32%) and TB (n = 23, 26%) related health services.

Table 4.

Summary of included studies

| Characteristic | Number of studies (n = 87) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Publication year | ||

| 2000–2002 | 2 | 2 |

| 2003–2005 | 4 | 5 |

| 2006–2008 | 12 | 14 |

| 2009–2011 | 25 | 29 |

| 2012–2014 | 31 | 36 |

| 2015–2016 | 13 | 15 |

| Study location | ||

| Africa | 57 | 66 |

| Asia | 16 | 18 |

| Europe | 2 | 2 |

| North America | 10 | 11 |

| South America | 2 | 2 |

| Disease area | ||

| HIV | 44 | 51 |

| TB | 23 | 26 |

| Malaria | 28 | 32 |

Evaluation methods used in the studies

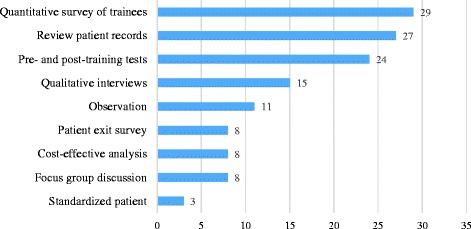

A wide range of training evaluation methods was used. As shown in Fig. 2, the most common method was a quantitative survey of trainees (n = 29, 33%). Methods such as reviewing patient records (n = 27, 31%) to assess diagnostic and treatment outcomes after HCPs attended training session and pre- and post-training tests (n = 24, 28%) were also applied frequently. In contrast, only three studies (3%) evaluated on-the-job behavior change of trainees using standardized patients.

Fig. 2.

Number of studies that apply each method

Outcomes assessed in the included studies

In terms of the outcomes evaluated among the included studies, more than half of the included studies (n = 44, 51%) evaluated knowledge acquisition (learning) of trainees after training sessions and 38 (44%) studies evaluated downstream results of the training programs. Fewer studies (n = 16, 18%) assessed whether trainees liked the program or whether the program was considered useful for trainees (reaction), and 30 (34%) measured the behavior change of trainees after they finished the training and returned to their jobs.

As summarized in Table 5, among the 16 studies evaluating trainees’ reaction, more than half (n = 9, 56%) conducted a quantitative survey with trainees after training and only two (13%) used pre- and post-training tests to investigate whether trainees liked the training programs or felt the programs were useful to them. In terms of the learning level, the most commonly used method was pre- and post-training tests (n = 23, 52%). Qualitative methods such as interviews (n = 4, 9%) or focus group discussion (n = 4, 9%) were also used, albeit less frequently, when assessing knowledge gain of trainees. Observation was used commonly when assessing behavior change of trainees (11, 37%). Quantitative survey with trainees (n = 9, 30%) and qualitative interviews (n = 7, 23%) were also used to record self-reported behavior change of trainees after training programs. Additionally, three studies (10%) used standardized patients when evaluating on-the-job performance of trainees after training sessions. Finally, in terms of results on an organizational level, review of patient records (n = 26, 68%) was the most commonly used method. Patient exit survey (n = 8, 21%) was also used to assess patients’ experiences and satisfaction with the services provided by trainees. Even though cost of the training programs was an important indicator for program managers and policy makers, only eight studies (21%) conducted evaluations on the cost of the programs.

Table 5.

Common evaluation methods for each level of the Kirkpatrick model

| Level of evaluation | Common methods used | Number of studiesa | Percentage (%) | Referencesa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction (n = 16) | Quantitative survey of trainees | 9 | 56 | [23, 32–39] |

| Qualitative interview | 5 | 31 | [40–44] | |

| Focus group discussion | 4 | 25 | [36, 38, 42, 45] | |

| Pre- and post-training tests | 2 | 13 | [46, 47] | |

| Learning (n = 44) | Pre- and post-training tests | 23 | 52 | [27, 33–35, 37, 43, 46–62] |

| Quantitative survey | 16 | 36 | [23, 45, 63–76] | |

| Qualitative interview | 4 | 9 | [44, 69, 77, 78] | |

| Focus group discussion | 4 | 9 | [51, 56, 78, 79] | |

| Behavior (n = 30) | Observation | 11 | 37 | [32, 33, 39, 42, 57, 63, 80–84] |

| Quantitative survey of trainees | 9 | 30 | [23, 45, 62, 64, 67, 70, 72, 77, 85] | |

| Qualitative interview | 7 | 23 | [44, 69, 77, 78, 86–88] | |

| Standardized patient | 3 | 10 | [56, 89, 90] | |

| Review patient records | 1 | 3 | [85] | |

| Pre- and post-training tests | 1 | 3 | [61] | |

| Results (n = 38) | Review patient records | 26 | 68 | [27, 28, 42, 57, 58, 66, 78, 80, 87, 91–107] |

| Patient exit survey | 8 | 21 | [35, 63, 67, 108–112] | |

| Cost-effective analysis | 8 | 21 | [33, 35, 42, 57, 92, 97, 108, 109] | |

| Quantitative survey of trainees | 2 | 5 | [113, 114] | |

| Qualitative interview | 1 | 3 | [78] |

aArticles may be double entered in this column

Discussion

Our paper provides the first synthesis of methods applied and outcomes assessed in studies evaluating HCP training for HIV, malaria, and TB service delivery. Overall, we found a fairly limited number of published evaluation studies of HCP training programs, especially in light of the number of training programs implemented since 2000. Among the 87 training evaluation studies identified, the most commonly applied assessment methods were quantitative surveys and reviews of patient records and the most commonly assessed outcomes were learning and downstream results. Specific gaps in the literature identified were evaluations of TB- and malaria-related HCP training, evaluations conducted in Asian countries with high disease burden, and studies providing objective information on behavior change of trainees or costs of training.

While a substantial proportion (51%) of studies assessed “learning” of trainees, we found that most used pre- and post-training tests. This is likely because tests can be conducted fairly easily after training sessions without further follow-up. However, knowledge assessments using pre- and post-training tests have limitations with many experts in psychology and education stressing that knowledge acquisition is a dynamic process that may not be captured through a simple paper-based assessment [17]. Tests at the end of the training sessions are best suited for testing retention of factual knowledge [21], but for most HCP training programs, improvements in service quality are as important as retained knowledge. Therefore, assessment of behavior change of HCPs after attending training programs is critical in determining whether the objectives of the training interventions have been achieved; our findings revealed that only 30 studies across all three diseases assessed behavior change. Furthermore, behavior change was most commonly assessed through direct observation of trainees’ on-the-job performance by evaluators, a method which would result in a high risk of bias because trainees’ behavior would likely be altered when evaluators observed their performance during consultations [22]. Surveys and qualitative interviews asking participants if they have applied newly acquired skills were other methods, also subject to bias, commonly used in assessing behavior change of trainees [23]. While self-reporting behavior may vary by cultural context, there is a risk that trainees may not be willing to reveal that they are not using the skills learned at the training sessions to evaluators, who are often involved in conducting the original training.

An alternative method for assessing the behavior of HCP is through the use of standardized patients, which refers to people trained to accurately portray a specific medical condition [24]. This method—used in some medical schools for evaluating clinical performance—provides a structured way for evaluators to capture trainees’ clinical competence and communication skills. Compared to direct observation, it minimizes bias because trainees do not know when a clinical encounter with standardized patients will occur [24, 25]. We found that this assessment method is rarely used in the evaluation of HCP training programs, possibly because it is resource and time consuming to find and train standardized patients.

In addition to assessing learning or knowledge gain, downstream results were also widely evaluated in HCP training programs. As part of these evaluations, researchers typically compared patient-level outcomes before and after training programs or between intervention and control groups by reviewing clinical records of patients who were treated by trainees participated in the training programs. For example, in TB control programs, indicators from standard guidelines, such as treatment success rate and case detection, were used as outcome indicators in evaluation of TB HCP training programs [26]. Likewise, in HIV-related training programs, indicators such as HIV testing rate and proportion of patients with undetectable viral loads were used as outcome indicators in the training evaluation [27, 28]. However, changes in downstream organizational results, such as improved case detection or treatment success rate used in TB training programs and proportion with undetectable viral loads in HIV training programs, cannot be simply attributed to HCP training programs using, for example, a before-after evaluation approach, because training programs are often embedded within a broader national control strategy with other prevention and control activities ongoing in parallel. Downstream health outcomes are challenging to assess as they are multifactorial and complex. Other factors, such as improved supply of medical equipment or enhanced healthcare infrastructure, may also contribute to better patient outcomes. These evaluations also tend to rely on routine patient records which may vary in accuracy and completeness.

When considering impact on the wider organization or disease control program, costs of training were not widely assessed. Only eight studies assessed the cost of the training programs, even though cost is an important indicator to policymakers in making decisions on resource allocation [29].

In this scoping review, the goal-based Kirkpatrick model was used in categorizing evaluation outcomes of included studies. Even though developed in the 1960s, the Kirkpatrick model is still the most commonly used evaluation framework and formed the foundation for other goal-based evaluation frameworks developed subsequently [12–18]. For example, in the Phillips model, a fifth level, return on investment (ROI), was added to the classic four-level Kirkpatrick model to assess the cost-benefit of the training [16]. Another example is the Hamblin’s five-level model, in which the result level in the Kirkpatrick model was split into two: organization and ultimate value [30]. The organization level assesses the impact on organization from the behavior changes of trainees, and the ultimate value measures the financial effects of the training program on the organization and the economy [30]. Apart from the goal-based models for training evaluation, which intend to determine whether the goals set before the start of the training were achieved, system-based models that focus on the assessment of the context and the process of the training program were also developed to guide the evaluation [31]. However, compared to goal-based models, very few system-based models provide detailed description of process involved and outcomes needed to be assessed in each step of the evaluation, which makes them less popular among evaluators [31].

In order to conduct a broad search of gray and published literature, we included three electronic databases, Google scholar, and six NGO websites and did not set language limits to exclude studies published in languages other than English. However, we recognize that we may have missed some HCP training evaluations if the studies were not published or accessible online. Additionally, since we intended to include published peer-reviewed evaluation studies, we did not analyze studies published as conference abstracts or presented as posters at conference in this review. As recognized in other scoping reviews as well, the quality of the included studies was not assessed, because the primary aim was to summarize the range of existing literature in terms of their volume, nature, and characteristics [21]. The lack of rigorous HCP training evaluation studies in current literature may reflect the limited knowledge, experience, and budget available to program managers or researchers in LMICs to conduct training evaluations. A limitation of our study is that we did not analyze qualitative information about challenges with conducting training evaluations mentioned in the studies identified; a further systematic review and analysis of the limitations mentioned in existing training evaluation studies or in interviews with program managers could be conducted in future to investigate barriers and difficulties encountered by evaluators when conducting training evaluations, particularly in LMICs. Such studies would be useful to identify strategies to increase the evidence base in this area. In addition, future studies on development of standardized training evaluation frameworks or methods would also be helpful to minimize biases in assessment, improve accountability of evaluation results, and make HCP training evaluation more relevant to policymakers.

Conclusions

Evaluations are critical to determine the effectiveness of HCP training in order to inform decisions on future investments. However, our study found limited evidence from robust evaluations conducted since 2000, even though the number of training interventions has increased over this period to address the shortage of HRH for HIV, malaria, and TB control globally. Specifically, we found a limited number of evaluation studies on TB- and malaria-related HCP training and very few studies assessing behavior change of trainees or costs of training. More evidence from well-designed HCP training evaluations is needed, and this may be facilitated by developments in frameworks and standardized methods to assess impacts of training.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The systematic review was supported by the National University of Singapore.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

SW designed the search strategy and conducted the literature search. SW and IR screened the titles and abstracts. SW conducted the analysis and drafted the article. MK provided advice at all stages. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- HCP

Healthcare provider

- HRH

Human resources for health

- LMICs

Low- and middle-income countries

- TB

Tuberculosis

- The Global Fund

The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria

Contributor Information

Shishi Wu, Email: shishi_wu@u.nus.edu.

Imara Roychowdhury, Email: imara_roychowdhury@nuhs.edu.sg.

Mishal Khan, Email: mishal.khan@lshtm.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Dräger S, Gedik G, Dal Poz M. Health workforce issues and the Global Fund to fight AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria: an analytical review. Hum Resour Health. 2006;4:23. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-4-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen L, Evans T, Anand S, Boufford J, Brown H, Chowdhury M, Cueto M. Human resources for health: overcoming the crisis. Lancet. 2004;364:1984–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17482-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu D, Souteyrand Y, Banda MA, Kaufman J, Perriens JH. Investment in HIV/AIDS programs: does it help strengthen health systems in developing countries? Glob Health. 2008;4:8. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruxin J, Paluzzi J, Wilson P, Tozan Y, Kruk M, Teklehaimanot A. Emerging consensus in HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, and access to essential medicines. Lancet. 2005;365:618–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)70806-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Victoria M, Granich R, Gilks C, Gunneberg C, Hosseini M, Were W, Raviglione M, Cock K. The global fight against HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;131:844–8. doi: 10.1309/AJCP5XHDB1PNAEYT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crisp N, Gawanas B, Sharp I. Training the health workforce: scaling up, saving lives. Lancet. 2008;371:689–91. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60309-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO. The World Health Report 2006: working together for health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. http://www.who.int/whr/2006/whr06_en.pdf?ua=. Accessed 11 Oct 2016.

- 8.Figueroa-Munoz J, Palmer K, Dal Poz M, Blanc L, Bergström K, Raviglione M. The health workforce crisis in TB control: a report from high-burden countries. Hum Resour Health. 2005;3:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Bowser D, Sparkes S, Mitchell A, Bossert T, Bärnighausen T, Gedik G, Atun R. Global Fund investments in human resources for health: innovation and missed opportunities for health systems strengthening. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29:986–97. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czt080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Global Fund. Results Report 2015. Geneva: The global fund to fight AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria; 2015. https://www.theglobalfund.org/media/2546/results_2015resultsreport_report_en.pdf. Accessed 11 Oct 2016.

- 11.Habicht J, Victora C, Vaughan J. Evaluation design for adequacy, plausibility and probability of public health programme performance and impact. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:10–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bates R. A critical analysis of evaluation practice: the Kirkpatrick model and the principle of beneficence. Eval Program Plann. 2004;27:341–7. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2004.04.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alliger G, Tannenbaum S, Bennett W, Traver H, Shotland A. A meta-analysis of the relations among training criteria. Pers Psychol. 1997;50:341–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1997.tb00911.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Omar M, Gerein N, Tarin E, Butcher C, Pearson S, Heidari G. Training evaluation: a case study of training Iranian health managers. Hum Resour Health. 2009;7:20. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-7-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morgan R, Casper W. Examining the factor structure of participant reactions to training: a multidimensional approach. Hum Resour Dev Q. 2000;11:301–17. doi: 10.1002/1532-1096(200023)11:3<301::AID-HRDQ7>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phillips P, Phillips J. Symposium on the evaluation of training. Int J Train Dev. 2001;5:240–247.

- 17.Kraiger K, Ford J, Salas E. Application of cognitive, skill-based, and affective theories of learning outcomes to new methods of training evaluation. J Appl Psychol. 1993;78:311–28. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.78.2.311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arthur W, Bennett W, Edens P, Bell S. Effectiveness of training in organizations: a meta-analysis of design and evaluation features. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88:234–45. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirkpatrick D, Kirkpatrick J. Evaluating training programs: the four levels (3rd Edition) California: Berrett-Koehler Publishers; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gagne R. The conditions of learning. New York: Holt, Rine-hart &Winston; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adair J. The Hawthorne effect: a reconsideration of the methodological artifact. J Appl Psychol. 1984;69:334–45. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.69.2.334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cicciò L, Makumbi M, Sera D. An evaluation study on the relevance and effectiveness of training activities in Northern Uganda. Rural Remote Health. 2010;10:1250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ebbert D, Connors H. Standardized patient experiences: evaluation of clinical performance and nurse practitioner student satisfaction. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2004;25:12–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siminoff LA, Rogers HL, Waller AC, Harris-Haywood S, Esptein RM, Carrio FB, Gliva-McConvey G, Longo DR. The advantages and challenges of unannounced standardized patient methodology to assess healthcare communication. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82:318–24. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.WHO. Compendium of indicators for monitoring and evaluating national tuberculosis programs. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/68768/1/WHO_HTM_TB_2004.344.pdf. Accessed 11 Oct 2016.

- 27.Koyio LN, Sanden WJ, Dimba E, Mulder J, Creugers NH, Merkx MA, van der Ven A, Frencken JE. Oral health training programs for community and professional health care workers in Nairobi East District increases identification of HIV-infected patients. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90927. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fairall L, Bachmann MO, Lombard C, Timmerman V, Uebel K, Zwarenstein M, Boulle A, Georgeu D, Colvin CJ, Lewin S, et al. Task shifting of antiretroviral treatment from doctors to primary-care nurses in South Africa (STRETCH): a pragmatic, parallel, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2012;380:889–98. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60730-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johns B, Baltussen R, Hutubessy R. Programme costs in the economic evaluation of health interventions. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2003;1:1. doi: 10.1186/1478-7547-1-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamblin AC. Evaluation and control of training. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zinovieff MA, Rotem A. Review and analysis of training impact evaluation methods, and proposed measures to support a United Nations system fellowships evaluation framework prepared. Geneva: WHO’s Department of Human Resources for Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bofill L, Weiss SM, Lucas M, Bordato A, Dorigo A, Fernandez-Cabanillas G, Aristegui I, Lopez M, Waldrop-Valverde D, Jones D. Motivational interviewing among HIV health care providers: challenges and opportunities to enhance engagement and retention in care in Buenos Aires, Argentina. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2015;14:491–6. doi: 10.1177/2325957415586257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hawkes M, Katsuva JP, Masumbuko CK. Use and limitations of malaria rapid diagnostic testing by community health workers in war-torn Democratic Republic of Congo. Malar J. 2009;8:308. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flys T, Gonzalez R, Sued O, Suarez Conejero J, Kestler E, Sosa N, McKenzie-White J, Monzon II, Torres CR, Page K. A novel educational strategy targeting health care workers in underserved communities in Central America to integrate HIV into primary medical care. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46426. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Onwujekwe O, Mangham-Jefferies L, Cundill B, Alexander N, Langham J, Ibe O, Uzochukwu B, Wiseman V. Effectiveness of provider and community interventions to improve treatment of uncomplicated malaria in Nigeria: a cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0133832. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sodhi S, Banda H, Kathyola D, Burciul B, Thompson S, Joshua M, Bateman E, Fairall L, Martiniuk A, Cornick R, et al. Evaluating a streamlined clinical tool and educational outreach intervention for health care workers in Malawi: the PALM PLUS case study. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2011;11(Suppl 2):S11. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-11-S2-S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cettomai D, Kwasa J, Birbeck GL, Price RW, Bukusi EA, Meyer AC. Training needs and evaluation of a neuro-HIV training module for non-physician healthcare workers in western Kenya. J Neurol Sci. 2011;307:92–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zolfo M, Iglesias D, Kiyan C, Echevarria J, Fucay L, Llacsahuanga E, de Waard I, Suarez V, Llaque WC, Lynen L. Mobile learning for HIV/AIDS healthcare worker training in resource-limited settings. AIDS Res Ther. 2010;7:35. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-7-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beach M, Roter D, Saha S, Korthuis P, Eggly S, Cohn J, Sharp V, Moore R, Wilson I. Impact of a brief patient and provider intervention to improve the quality of communication about medication adherence among HIV patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:1078–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gutin SA, Cummings B, Jaiantilal P, Johnson K, Mbofana F, Dawson Rose C. Qualitative evaluation of a Positive Prevention training for health care providers in Mozambique. Eval Program Plann. 2014;43:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Puchalski Ritchie L, Lettow M, Barnsley J, Chan A, Schull M, Martiniuk A, Makwakwa A, Zwarenstein M. Lay health workers experience of a tailored knowledge translation intervention to improve job skills and knowledge: a qualitative study in Zomba district Malawi. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Dick J, Clarke M, van Zyl H, Daniels K. Primary health care nurses implement and evaluate a community outreach approach to health care in the South African agricultural sector. Int Nurs Rev. 2007;54:383–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2007.00566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kamiru HN, Ross MW, Bartholomew LK, McCurdy SA, Kline MW. Effectiveness of a training program to increase the capacity of health care providers to provide HIV/AIDS care and treatment in Swaziland. AIDS Care. 2009;21:1463–70. doi: 10.1080/09540120902883093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Felderman-Taylor J, Valverde M. A structured interview approach to evaluate HIV training for medical care providers. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2007;18:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blanas DA, Ndiaye Y, Nichols K, Jensen A, Siddiqui A, Hennig N. Barriers to community case management of malaria in Saraya, Senegal: training, and supply-chains. Malar J. 2013;12:95. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Magee E, Tryon C, Forbes A, Heath B, Manangan L. The National Tuberculosis Surveillance System training program to ensure accuracy of tuberculosis data. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2011;17:427–30. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e31820f8e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Collins P, Mestry K, Wainberg M, Nzama T, Lindegger G. Training South African mental health care providers to talk about sex in the era of AIDS. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:1644–1647. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.11.1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li L, Wu Z, Liang LJ, Lin C, Guan J, Jia M, Rou K, Yan Z. Reducing HIV-related stigma in health care settings: a randomized controlled trial in China. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:286–92. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vanden Driessche K, Sabue M, Dufour W, Behets F, Van Rie A. Training health care workers to promote HIV services for patients with tuberculosis in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Hum Resour Health. 2009;7:23. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-7-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chang LW, Kadam DB, Sangle S, Narayanan S, Borse RT, McKenzie-White J, Bowen CW, Sisson SD, Bollinger RC. Evaluation of a multimodal, distance learning HIV management course for clinical care providers in India. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2012;11:277–82. doi: 10.1177/1545109712451330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vaz M, Page J, Rajaraman D, Rashmi D, Silver S. Enhancing the education and understanding of research in community health workers in an intervention field site in South India. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2014;5:178–182. doi: 10.5958/0976-5506.2014.00299.X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rakhshani F, Mohammadi M. Improving community health workers’ knowledge and behaviour about proper content in malaria education. J Pak Med Assoc. 2009;59:3995–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van der Elst E, Smith A, Gichuru E, Wahome E, Musyoki H, Muraguri N, Fegan G, Duby Z, Bekker L, Bender B, et al. Men who have sex with men sensitivity training reduces homoprejudice and increases knowledge among Kenyan healthcare providers in coastal Kenya. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(Suppl 3):18748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Awaisu A, Mohamed M, Noordin N, Abd. Aziz N, Sulaiman S, Muttalif A, Mahayiddin A. Potential impact of a pilot training program on smoking cessation intervention for tuberculosis DOTS providers in Malaysia. J Public Health. 2010;18:279–288.

- 55.Wu PS, Chou P, Chang NT, Sun WJ, Kuo HS. Assessment of changes in knowledge and stigmatization following tuberculosis training workshops in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2009;108:377–85. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Renju J, Andrew B, Nyalali K, Kishamawe C, Kato C, Changalucha J, Obasi A. A process evaluation of the scale up of a youth-friendly health services initiative in northern Tanzania. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010;13:32. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kyabayinze DJ, Asiimwe C, Nakanjako D, Nabakooza J, Bajabaite M, Strachan C, Tibenderana JK, Van Geetruyden JP. Programme level implementation of malaria rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) use: outcomes and cost of training health workers at lower level health care facilities in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:291. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ssekabira U, Bukirwa H, Hopkins H, Namagembe A, Weaver MR, Sebuyira LM, Quick L, Staedke S, Yeka A, Kiggundu M, et al. Improved malaria case management after integrated team-based training of health care workers in Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:826–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weaver MR, Crozier I, Eleku S, Makanga G, Mpanga Sebuyira L, Nyakake J, Thompson M, Willis K. Capacity-building and clinical competence in infectious disease in Uganda: a mixed-design study with pre/post and cluster-randomized trial components. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51319. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Capital Ka Cyrilliciriazova TK, Neduzhko OO, Kang Dufour M, Culyba RJ, Myers JJ. Evaluation of the effectiveness of HIV voluntary counseling and testing trainings for clinicians in the Odessa region of Ukraine. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(Suppl 1):S89–95. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0545-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mulligan R, Seirawan H, Galligan J, Lemme S. The effect of an HIV/AIDS educational program on the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of dental professionals. J Dent Educ. 2006;70:857–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kabra SK, Mukherjee A, Vani SA, Sinha S, Sharma SK, Mitsuyasu R, Fahey JL. Continuing medical education on antiretroviral therapy in HIV/AIDS in India: needs assessment and impact on clinicians and allied health personnel. Natl Med J India. 2009;22:257–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rowe AK, de Leon GF, Mihigo J, Santelli AC, Miller NP, Van-Dunem P. Quality of malaria case management at outpatient health facilities in Angola. Malar J. 2009;8:275. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alam N, Mridha MK, Kristensen S, Vermund SH. Knowledge and skills for management of sexually transmitted infections among rural medical practitioners in Bangladesh. Open J Prev Med. 2015;5:151–8. doi: 10.4236/ojpm.2015.54018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu Z, Detels R, Ji G, Xu C, Rou K, Ding H, Li V. Diffusion of HIV/AIDS knowledge, positive attitudes, and behaviors through training of health professionals in China. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002;14:379–90. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.6.379.24074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Operario D, Wang D, Zaller ND, Yang MF, Blaney K, Cheng J, Hong Q, Zhang H, Chai J, Szekeres G, et al. Effect of a knowledge-based and skills-based programme for physicians on risk of sexually transmitted reinfections among high-risk patients in China: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4:e29–36. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00249-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ouma PO, Van Eijk AM, Hamel MJ, Sikuku E, Odhiambo F, Munguti K, Ayisi JG, Kager PA, Slutsker L. The effect of health care worker training on the use of intermittent preventive treatment for malaria in pregnancy in rural western Kenya. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:953–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Domarle O, Randrianarivelojosia M, Duchemin JB, Robert V, Ariey F. Atelier paludisme: an international malaria training course held in Madagascar. Malar J. 2008;7:80. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.O’Malley G, Beima-Sofie K, Feris L, Shepard-Perry M, Hamunime N, John-Stewart G, Kaindjee-Tjituka F, Brandt L, group Ms “If I take my medicine, I will be strong”: evaluation of a pediatric HIV disclosure intervention in Namibia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68:e1–7. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Poudyal A, Jimba M, Murakami I, Silwal R, Wakai S, Kuratsuji T. A traditional healers’ training model in rural Nepal: strengthening their roles in community health. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:956–960. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Heunis C, Wouters E, Kigozi G, van Rensburg-Bonthuyzen Janse E, Jacobs N. TB/HIV-related training, knowledge and attitudes of community health workers in the Free State province, South Africa. Afr J AIDS Res. 2013;12:113–9. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2013.855641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Peltzer K, Mngqundaniso N, Petros G. A controlled study of an HIV/AIDS/STI/TB intervention with traditional healers in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2006;10:683–90. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9110-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Peltzer K, Nqeketo A, Petros G, Kanta X. Evaluation of a safer male circumcision training programme for traditional surgeons and nurses in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2008;5:346–54. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v5i4.31289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Matsabisa M, Spotose T, Hoho D, Javu M. Traditional health practitioners’ awareness training programme on TB, HIV and AIDS: a pilot project for the Khayelitsha area in Cape Town, South Africa. J Med Plant Res. 2009;3:142–7. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Adams LV, Olotu R, Talbot EA, Cronin BJ, Christopher R, Mkomwa Z. Ending neglect: providing effective childhood tuberculosis training for health care workers in Tanzania. Public Health Action. 2014;4:233–7. doi: 10.5588/pha.14.0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Köse S, Mandiracioglu A, Kaptan F, Gülsen M. Improving knowledge and attitudes of health care providers following training on HIV/AIDS related issues: a study in an urban Turkish area. J Med Sci. 2012;32:94–103. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hanass-Hancock J, Alli F. Closing the gap: training for healthcare workers and people with disabilities on the interrelationship of HIV and disability. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37:2012–21. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2014.991455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Downing J, Kawuma E. The impact of a modular HIV/AIDS palliative care education programme in rural Uganda. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2008;14:560–8. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2008.14.11.31761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.van der Elst EM, Gichuru E, Omar A, Kanungi J, Duby Z, Midoun M, Shangani S, Graham SM, Smith AD, Sanders EJ, Operario D. Experiences of Kenyan healthcare workers providing services to men who have sex with men: qualitative findings from a sensitivity training programme. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(Suppl 3):18741. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.4.18741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Skarbinski J, Ouma PO, Causer LM, Kariuki SK, Barnwell JW, Alaii JA, de Oliveira AM, Zurovac D, Larson BA, Snow RW, et al. Effect of malaria rapid diagnostic tests on the management of uncomplicated malaria with artemether-lumefantrine in Kenya: a cluster randomized trial. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:919–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Brentlinger PE, Assan A, Mudender F, Ghee AE, Vallejo Torres J, Martinez Martinez P, Bacon O, Bastos R, Manuel R, Ramirez Li L, et al. Task shifting in Mozambique: cross-sectional evaluation of non-physician clinicians’ performance in HIV/AIDS care. Hum Resour Health. 2010;8:23. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-8-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mukanga D, Babirye R, Peterson S, Pariyo GW, Ojiambo G, Tibenderana JK, Nsubuga P, Kallander K. Can lay community health workers be trained to use diagnostics to distinguish and treat malaria and pneumonia in children? Lessons from rural Uganda. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16:1234–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Namagembe A, Ssekabira U, Weaver MR, Blum N, Burnett S, Dorsey G, Sebuyira LM, Ojaku A, Schneider G, Willis K, Yeka A. Improved clinical and laboratory skills after team-based, malaria case management training of health care professionals in Uganda. Malar J. 2012;11:44. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Counihan H, Harvey SA, Sekeseke-Chinyama M, Hamainza B, Banda R, Malambo T, Masaninga F, Bell D. Community health workers use malaria rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) safely and accurately: results of a longitudinal study in Zambia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87:57–63. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bruno TO, Hicks CB, Naggie S, Wohl DA, Albrecht H, Thielman NM, Rabin DU, Layton S, Subramaniam C, Grichnik KP, et al. VISION: a regional performance improvement initiative for HIV health care providers. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2014;34:171–8. doi: 10.1002/chp.21248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Atchessi N, Ridde V, Haddad S. Combining user fees exemption with training and supervision helps to maintain the quality of drug prescriptions in Burkina Faso. Health Policy Plan. 2013;28:606–15. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tadesse Y, Yesuf M, Williams V. Evaluating the output of transformational patient-centred nurse training in Ethiopia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17:9–14. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.13.0386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lalonde B, Uldall KK, Huba GJ, Panter AT, Zalumas J, Wolfe LR, Rohweder C, Colgrove J, Henderson H, German VF, et al. Impact of HIV/AIDS education on health care provider practice: results from nine grantees of the Special Projects of National Significance Program. Eval Health Prof. 2002;25:302–20. doi: 10.1177/0163278702025003004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Li L, Lin C, Guan J. Using standardized patients to evaluate hospital-based intervention outcomes. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:897–903. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Aung T, Longfield K, Aye NM, San AK, Sutton TS, Montagu D, Group PHUGH Improving the quality of paediatric malaria diagnosis and treatment by rural providers in Myanmar: an evaluation of a training and support intervention. Malar J. 2015;14:397. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0923-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Talukder K, Salim MA, Jerin I, Sharmin F, Talukder MQ, Marais BJ, Nandi P, Cooreman E, Rahman MA. Intervention to increase detection of childhood tuberculosis in Bangladesh. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:70–5. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Vaca J, Peralta H, Gresely L, Cordova R, Kuffo D, Romero E, Tannenbaum TN, Houston S, Graham B, Hernandez L, Menzies D. DOTS implementation in a middle-income country: development and evaluation of a novel approach. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9:521–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Christie CD, Steel-Duncan J, Palmer P, Pierre R, Harvey K, Johnson N, Samuels LA, Dunkley-Thompson J, Singh-Minott I, Anderson M, et al. Paediatric and perinatal HIV/AIDS in Jamaica an international leadership initiative, 2002–2007. West Indian Med J. 2008;57:204–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Park PH, Magut C, Gardner A, O’Yiengo DO, Kamle L, Langat BK, Buziba NG, Carter EJ. Increasing access to the MDR-TB surveillance programme through a collaborative model in western Kenya. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17:374–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02933.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zurovac D, Githinji S, Memusi D, Kigen S, Machini B, Muturi A, Otieno G, Snow RW, Nyandigisi A. Major improvements in the quality of malaria case-management under the “test and treat” policy in Kenya. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92782. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Puchalski Ritchie LM, Schull MJ, Martiniuk AL, Barnsley J, Arenovich T, van Lettow M, Chan AK, Mills EJ, Makwakwa A, Zwarenstein M. A knowledge translation intervention to improve tuberculosis care and outcomes in Malawi: a pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. Implement Sci. 2015;10:38. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0228-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fairall L, Bachmann MO, Zwarenstein M, Bateman ED, Niessen LW, Lombard C, Majara B, English R, Bheekie A, van Rensburg D, et al. Cost-effectiveness of educational outreach to primary care nurses to increase tuberculosis case detection and improve respiratory care: economic evaluation alongside a randomised trial. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15:277–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Clarke M, Dick J, Zwarenstein M, Lombard CJ, Diwan VK. Lay health worker intervention with choice of DOT superior to standard TB care for farm dwellers in South Africa: a cluster randomised control trial. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9:673–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lewin S, Dick J, Zwarenstein M, Lombard CJ. Staff training and ambulatory tuberculosis treatment outcomes: a cluster randomized controlled trial in South Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:250–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Manabe YC, Zawedde-Muyanja S, Burnett SM, Mugabe F, Naikoba S, Coutinho A. Rapid improvement in passive tuberculosis case detection and tuberculosis treatment outcomes after implementation of a bundled laboratory diagnostic and on-site training intervention targeting mid-level providers. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015;2:ofv030. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofv030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ngasala B, Mubi M, Warsame M, Petzold MG, Massele AY, Gustafsson LL, Tomson G, Premji Z, Bjorkman A. Impact of training in clinical and microscopy diagnosis of childhood malaria on antimalarial drug prescription and health outcome at primary health care level in Tanzania: a randomized controlled trial. Malar J. 2008;7:199. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Eriksen J, Mujinja P, Warsame M, Nsimba S, Kouyate B, Gustafsson LL, Jahn A, Muller O, Sauerborn R, Tomson G. Effectiveness of a community intervention on malaria in rural Tanzania—a randomised controlled trial. Afr Health Sci. 2010;10:332–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mubi M, Janson A, Warsame M, Martensson A, Kallander K, Petzold MG, Ngasala B, Maganga G, Gustafsson LL, Massele A, et al. Malaria rapid testing by community health workers is effective and safe for targeting malaria treatment: randomised cross-over trial in Tanzania. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19753. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mbonye MK, Burnett SM, Burua A, Colebunders R, Crozier I, Kinoti SN, Ronald A, Naikoba S, Rubashembusya T, Van Geertruyden JP, et al. Effect of integrated capacity-building interventions on malaria case management by health professionals in Uganda: a mixed design study with pre/post and cluster randomized trial components. PLoS One. 2014;9:e84945. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Weaver MR, Burnett SM, Crozier I, Kinoti SN, Kirunda I, Mbonye MK, Naikoba S, Ronald A, Rubashembusya T, Zawedde S, Willis KS. Improving facility performance in infectious disease care in Uganda: a mixed design study with pre/post and cluster randomized trial components. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Morris MB, Chapula BT, Chi BH, Mwango A, Chi HF, Mwanza J, Manda H, Bolton C, Pankratz DS, Stringer JS, Reid SE. Use of task-shifting to rapidly scale-up HIV treatment services: experiences from Lusaka, Zambia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Audet CM, Gutin SA, Blevins M, Chiau E, Alvim F, Jose E, Vaz LM, Shepherd BE, Dawson Rose C. The impact of visual aids and enhanced training on the delivery of positive health, dignity, and prevention messages to adult patients living with HIV in rural north central Mozambique. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130676. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mangham-Jefferies L, Wiseman V, Achonduh OA, Drake TL, Cundill B, Onwujekwe O, Mbacham W. Economic evaluation of a cluster randomized trial of interventions to improve health workers’ practice in diagnosing and treating uncomplicated malaria in Cameroon. Value Health. 2014;17:783–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wiseman V, Mangham-Jefferies L, Achonduh O, Drake T, Cundill B, Onwujekwe O, Mbacham W. Economic evaluation of interventions to improve health workers’ practice in diagnosing and treating uncomplicated malaria in Cameroon. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;91(5 Suppl. 1):268. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 110.Mbacham WF, Mangham-Jefferies L, Cundill B, Achonduh OA, Chandler CI, Ambebila JN, Nkwescheu A, Forsah-Achu D, Ndiforchu V, Tchekountouo O, et al. Basic or enhanced clinician training to improve adherence to malaria treatment guidelines: a cluster-randomised trial in two areas of Cameroon. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e346–58. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70201-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Nyandigisi A, Memusi D, Mbithi A, Ang’wa N, Shieshia M, Muturi A, Sudoi R, Githinji S, Juma E, Zurovac D. Malaria case-management following change of policy to universal parasitological diagnosis and targeted artemisinin-based combination therapy in Kenya. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24781. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rose CD, Courtenay-Quirk C, Knight K, Shade SB, Vittinghoff E, Gomez C, Lum PJ, Bacon O, Colfax G. HIV intervention for providers study: a randomized controlled trial of a clinician-delivered HIV risk-reduction intervention for HIV-positive people. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:572–81. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ee4c62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bin Ghouth AS. Availability and prescription practice of anti-malaria drugs in the private health sector in Yemen. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2013;7:404–12. doi: 10.3855/jidc.2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ohkado A, Pevzner E, Sugiyama T, Murakami K, Yamada N, Cavanaugh S, Ishikawa N, Harries AD. Evaluation of an international training course to build programmatic capacity for tuberculosis control. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14:371–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.