Abstract

Objective

To evaluate construct validity and scoring methods of the world health organization- health and work performance questionnaire (HPQ) for people with arthritis.

Methods

Construct validity was examined through hypothesis testing using the recommended guidelines of the Consensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN).

Results

The HPQ using the absolute scoring method showed moderate construct validity as 4 of the 7 hypotheses were met. The HPQ using the relative scoring method had weak construct validity as only one of the 7 hypotheses were met.

Conclusion

The absolute scoring method for the HPQ is superior in construct validity to the relative scoring method in assessing work performance among people with arthritis and related rheumatic conditions; however, more research is needed to further explore other psychometric properties of the HPQ.

The World Health Organization - Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ) is an assessment of work functioning based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), a widely accepted disablement and enablement conceptual framework from the World Health organization (1). Work functioning is an umbrella term which encompasses work activity (execution of work-related tasks) and work participation (involvement in work roles or the lived experience of work) (2). While there are numerous assessments of work functioning recommended for use among people with arthritis; the literature evaluating the psychometric qualities is of low quality (3). To date, there are no gold standards for measuring work functioning for people with arthritis and rheumatological conditions. Thus, valid and reliable assessment tools are still needed.

The HPQ is a promising tool used to ascertain work outcomes among people with chronic conditions such as depression and traumatic brain injury (4,5). The tool has established validity and reliability among populations of people with and without chronic conditions (4–6); however, its psychometric properties have not been tested among people with arthritis. The HPQ has three subscales: sickness absence, work functioning, and critical incidences at work. The work functioning subscale includes three items that asks the participant to rate his/her own performance at work, to rate others, and finally to rate themselves in comparison with how others perform the same job. This approach is considered innovative as comparisons allow evaluation of work functioning to all job types, and not limited to some certain work tasks, like some commonly used assessments of work functioning in arthritis research.

Work functioning has been captured using a variety of instruments in the past for people with arthritis. Many of which, however, include conceptually mixed dimensions of work functioning making it difficult to compare instruments to establish validity. The Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ), widely used in arthritis work outcomes research, is one of the instruments with the highest quality evidence supporting its’ psychometric properties (3). The WLQ has four subscales: time demands, mental/interpersonal demands, physical demands and output demands (7). Of these subscales, the output demands captures a similar dimension of work functioning as the HPQ and could be used to evaluate construct validity of the HPQ.

Construct validity is defined as the degree to which an instrument is consistent with hypotheses based on the assumption that the instrument validity measures the construct to be measured (8). For the HPQ, construct validity can be examined through testing hypotheses based on associations of assessments which measure a similar construct (such as the WLQ), and previously identified risk factors with work functioning limitations from the literature when other assessments of similar constructs are lacking in the same study.

According to the Work Activity and Participation Outcome (Work APO) framework, work disability is the opposite of work functioning (2). Risk factors of work disability, defined as work activity limitation and work participation restriction, among people with arthritis and rheumatological conditions have been studied in the past. One form of work disability is work cessation, defined as leaving work permanently. Work cessation has been studied extensively in the literature as it is a permanent outcome with financial consequences on individuals and society. In a recent systematic review of predictive factors of work cessation, physical job demands, older age and low education were the strongest predictors(9). Allaire et al. conducted a study on a national US cohort and also found that older age was a significant predictor in addition to working fewer hours (10). Lacaille et al. investigated modifiable work-related risk factors on work cessation for people with rheumatoid arthritis and found that lower physical functioning, higher pain and lower self-efficacy were significant determinants of work cessation (11). Meanwhile, other studies investigated the risk factors of other aspects of work disability, such as work activity limitation. Determinants of work activity limitations include physical functioning (12,13), education level (14), and jobs considered as manual labor (15). Considering that determinants of work cessation are more established in the literature than determinants of work activity limitation, both will be used to will be used to formulate hypotheses to examine construct validity of the HPQ for persons with arthritis and rheumatological conditions.

The developers of the HPQ reference two methods of scoring, relative and absolute. The relative score is obtained from a ratio between the persons’ perception of how they are performing at work compared to others, while the absolute score is a percentage obtained from the person’s perception of how they performed at work in the past four weeks. The developers of the HPQ did not specify whether the relative or absolute scoring methods should be used, or if one is more meaningful or superior in explaining the HPQ’s ability to assess work functioning, so a study to explore differences in scoring methods of the HPQ could be informative.

The aims of this study were to: 1) investigate the construct validity of the HPQ among people with arthritis and rheumatological conditions through hypotheses testing, and 2) explore differences between the HPQ absolute and relative scoring methods.

Methods

Materials and data collection

Baseline data from the “Work it” study in the Center for Enhancing Activity and Participation among people with Arthritis (ENACT) at Boston University were used for this study. The “Work it” study is a clinical trial designed to test the efficacy of a work barrier identification and problem-solving educational program on reducing work limitations (16). Participants were people who self-reported arthritis and a concern about their ability to continue working for the next few years due to their health conditions. Participants were recruited using several mechanisms including doctors’ office staff, medical registries, newspaper advertisements, online (e.g., Craigslist), national foundations (Arthritis Foundation), community flyers, and direct marketing.

The inclusion criteria were: 1) ages 21 to 65 years, 2) residents of Massachusetts, 3) self-report of arthritis or another rheumatological condition such as lupus, scleroderma or fibromyalgia, or chronic low back pain, 4) self-reported work of 15 hours or more a week, and 5) a positive response to the following question “Do you have any concern about being employed now or in the near future because of your health condition?” After the participants were screened for eligibility, they were mailed a welcome packet with detailed information about the study, two copies of the consent form, and a stamped and addressed envelope. Interested participants returned the consent and were scheduled for a baseline telephone interview. After the baseline interview, participants were randomized, and then data were collected by telephone at 6, 12 and 24-months.

Measures

HPQ work performance subscale

The main outcome of this study was the HPQ work functioning subscale (6). For this study, only the work functioning subscale was used. This subscale consists of three items (e.g. “On a scale from 0–10, where 0 is the worst job performance and 10 is the performance of a top worker, how would you rate the usual performance of most workers in a job similar to yours?”). The second and third items use the same 0–10 scale but ask the participant to rate their usual performance over the past year or two, and in the past four weeks. Two scores can be generated from these items: 1) the absolute score: a percentage (0–100%, where = 0 worst job performance) obtained from the individuals’ perception of how they performed at work in the last four weeks, and 2) the relative score: a ratio between how the person performed in the last week compared to how other workers perform. The relative score has a restricted range between 0.25 and 2.0 (0.25 worst relative performance or 25% less of other workers’ performance). The question asking participants to rate their performance in the past year or two is not used in generating the scores, but instead is used as a synthetic bounded recall question, designed to prime the respondent to give a more accurate answer for the question on the last four weeks.

Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ)

This instrument assesses work functioning limitations in the persons’ ability to perform work activities due to a health condition. It and consists of four separate scales. To limit respondent burden, only the output demands scale was used. The responses for the proportion of time of performing work tasks with difficulty range from none of the time (0%), to all of the time (100%). One of the five items was inadvertently left off the WLQ scale, however the scale does allow for the mean of the items to be used if fewer than 2 items are missing, so the scores are provided by the mean of the 4 non-missing items. The WLQ has evidence of good validity and reliability in assessing work functioning limitation (7,17).

Self-efficacy

Five items were used to assess job self-efficacy using questions developed in previous studies of vocational rehabilitation job retention program(18,19). These items specifically ask participants about their confidence in deciding and talking to employers and coworkers about their health condition at work (e.g. how confident are you about deciding whether or not to tell an employer about your health related work problems?). Scores range from 1 (not confident) to 4 (very confident).

Pain, job satisfaction, fatigue and stress

10mm visual analogue scales (VAS) were used to ascertain pain, job satisfaction, fatigue and stress. Pain VAS measures are reliable and valid and frequently used in research(20). In this study, we asked participants, “On a scale from 0 to 10 where 0 is the least pain and 10 is the most pain imaginable, how severe has your pain been on average at the end of your work day during the past week?” Job satisfaction, fatigue, and stress were also assessed in the context of work using the same scale and approach.

Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ)

This tool was used to measure participants’ functional status. It has been used previously among people with various rheumatic conditions including rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, psoriatic arthritis and more. The HAQ has 20 items divided into eight categories (dressing and grooming, arising, eating, walking, hygiene, reaching, gripping, and instrumental daily activities) and response options range from 0–3 (e.g. Are you able to shampoo your hair?) Responses range from (0: without any difficulty and 3: unable to do). Total HAQ score is obtained from summing the scores of each category and dividing by number of categories answered. To obtain a HAQ index score of 0–3 where increasing scores indicate worse functioning. This instrument has established reliability and validity in assessing functional status for samples of people with arthritis (21).

Job type

Job type: job titles were classified according to Department of Labor jobs classification (22). The participants were grouped into two main job categories. The first group worked in managerial and professional jobs, and the second group worked in sales, services, natural resources, construction and maintenance, production, transportation and moving, and military specific occupations.

Number of jobs

Number of jobs a person is working, hours worked per week, and number of days missed in the past three months because of health condition.

Arthritis type and demographic variables

Arthritis type and demographic variables including age, sex, marital status, ethnicity, highest educational attainment.

Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS software, version 9.4. Testing of normality of the distribution of the HPQ data was performed, and descriptive statistics including mean scores, standard deviations (SD), and range were calculated for the both the absolute and the relative scores of the HPQ.

Construct validity was evaluated using hypotheses testing guidelines of the Consensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN). The COSMIN standards define construct validity as “the degree of which the scores of a measurement instrument are consistent with the hypotheses, with regard to internal relationships, relationships with scores of other instruments or differences between relevant groups” (23). One way of addressing construct validity is through hypotheses testing. The COSMIN guidelines recommend that hypotheses are formed a priori with specific and clearly defined direction, magnitude and rationale (8). The first and last authors (RA & JK) came to a consensus about 7 independent hypotheses. In each of our formulated hypotheses, the anticipated (Spearman or Pearson) correlation direction, magnitude, according to Cohen’s estimates of correlation strength (24), and a rationale, from which the hypothesis was based, were clearly defined. Table 3 includes the hypotheses along with their rationales. The basis of the hypotheses were formed to reflect that the HPQ evaluates the construct of work performance, to confirm this; we expected that the Work Limitations Questionnaire would be correlated as it measures a similar construct (time affected at work because of work limitations). The data available for this study did not include any other assessments which were of similar constructs to the HPQ, consequently we used data from the literature describing how work disability as an outcome is different among groups based on some demographic factors such as age (10,18,25), education level (10,25,26), job type (10), physical function (9,10,27), and pain level (9,19). The consistency and magnitude of difference found in the literature between these factors and work disability influenced the hypotheses formation. The target population in searching for these factors was people with arthritis or rheumatological conditions. Associations for continuous variables were estimated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient, for categorical variables Spearman correlation and difference in means between groups were used to determine association. Construct validity rating for the HPQ was based on the total number of confirmed hypotheses: High, 5–6 of 6(≥75%); Moderate, 3–4 of 6(50%≤ x<75%); or Poor, 0–2 of 6(<50%). (8)

Table 3.

Hypotheses for testing construct validity of the HPQ

| Hypotheses | Rationale | Correlation expected | HPQ Absolute | HPQ Relative | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation actual | Confirmed? | Correlation actual | Confirmed? | |||

| 1. There will be at least a moderate-strong negative correlation between the HPQ* and WLQ** | HPQ and WLQ measure similar constructs but asked differently (actual performance versus time of disturbed performance at work) | −0.4 | −0.41 | Yes | −0.25 | No |

| 2.There will be at least a weak to moderate positive correlation between HPQ and age | Older age has been identified in literature as a risk factor for work cessation (loosely related construct to work performance) | 0.2 | 0.2 | Yes | 0.07 | No |

| 3. There will be at least a weak to moderate negative correlation between HPQ and education | Lower education has been identified in literature as a risk factor for work cessation (loosely related construct to work performance) | −0.2 | −0.07 | No | −0.04 | No |

| 4. There will be at least a weak to moderate negative correlation between HPQ and HAQ score | Lower physical function has been identified as a risk factor for work cessation (loosely related construct to work performance) | −0.2 | −0.15 | No | −0.14 | No |

| 5. There will be at least a weak to moderate negative correlation between HPQ and job type (non-professional as reference group) | Non-professional jobs have been identified in literature as a risk factor for work cessation (loosely related construct to work performance) | −0.2 | 0.05 | No | 0.07 | No |

| 6. There will be at least a weak negative correlation between HPQ and pain score | Pain has been identified in the literature as correlate of work performance in one occasion only | −0.1 | −0.11 | Yes | −0.14 | Yes |

| 7. There will be at least a weak to moderate positive correlation between HPQ and self efficacy | Self efficacy has been identified in the literature as a correlate of work performance in at least two occasions | 0.2 | 0.29 | Yes | 0.05 | No |

HPQ: Health Performance Questionnaire

WLQ: Work Limitations Questionnaire

Correlation strength: r ≥ 0.5, Strong; 0.5 > r ≥ 0.4, Moderate-Strong; 0.4 > r ≥ 0.3, Moderate; 0.3 > r ≥ 0.2, Weak-Moderate; 0.2 > r ≥ 0.1, Weak; and 0.1 > r, Negligible.

Overall construct validity was assigned based on percent of total hypotheses confirmed: High ≥75%; Moderate, 50%≤ × <75%); or Poor <50%.

Differences in scoring methods of HPQ

Differences in scoring methods of HPQ: differences in the HPQ relative and absolute scores for the previously mentioned variables were further explored through conducting an exploratory regression analysis.

To ensure that the sample size would be adequate for the planned analyses, the Power procedure in SAS was used to estimate the width of 95% confidence intervals for the correlations that would be obtained in analyses based on the sample size.(28). An estimated correlation of 0.80 (strong correlation) would have a 95% confidence interval extending from 0.75 to 0.84, which would allow us to exclude low or moderate levels of association.

Results

Demographics and distribution

The demographic and disease characteristics for the study sample can be found in Table 1. The sample consisted of 287 participants with a mean age of 50.4 years. The sample was mainly female, white, with some college education or higher, and predominantly single (44.5%). The sample had some degree of functional limitations (HAQ=0.8). 45.6% of the participants worked in managerial and professional jobs, and the remainder worked in sales, services, natural resources, construction and maintenance, production, transportation and moving, and military specific occupations. (See Table 2)

Table 1.

Demographics of sample

| Characteristic | Number (n= 287) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age | ||

| 21–29 | 17 | 5.9 |

| 30–39 | 32 | 11.1 |

| 40–49 | 57 | 19.9 |

| 50–59 | 122 | 42.5 |

| 60+ | 59 | 20.6 |

|

| ||

| Sex | ||

| Male | 78 | 27.2 |

| Female | 209 | 72.8 |

|

| ||

| Race | ||

| White | 198 | 69.2 |

| Black or African American | 61 | 21.3 |

| Other | 27 | 9.5 |

|

| ||

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 39 | 13.6 |

| Some college or college | 163 | 56.8 |

| Some graduate school or more | 85 | 29.6 |

|

| ||

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 100 | 34.8 |

| Single | 127 | 44.3 |

| Other | 60 | 20.9 |

|

| ||

| Diagnosis* | ||

| Osteoarthritis | 122 | 42.5 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 66 | 30.0 |

| Lupus | 32 | 11.1 |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 16 | 5.6 |

| Fibromyalgia | 33 | 11.5 |

| Chronic lower back pain | 46 | 16.0 |

| Other | 18 | 6.3 |

|

| ||

| Job type | ||

| Management, professional and related occupations | 128 | 44.6 |

| Sales, service and other occupations** | 159 | 55.4 |

Participant could have reported more than one condition.

Other occupation includes natural resources, construction and maintenance, production, transportation and moving, and military specific occupations

Table 2.

Outcomes for sample (N=287)

| Variable | Mean | Stan. Dev. | Range | Lower 95% CL | Upper 95% CL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical function | 1.22 | 0.56 | (0–2.75) | 1.15 | 1.28 |

| WLQ-output demands* | 35.2 | 21.4 | (0–100) | 32.76 | 37.76 |

| Self-efficacy | 2.6 | 0.8 | (0–4) | 2.53 | 4.05 |

| Hours worked per week | 36.2 | 14.3 | (15–160) | 34.56 | 37.88 |

| Missed days in past month | 3.2 | 7.1 | (0–30) | 2.39 | 4.05 |

| Job satisfaction | 6.5 | 2.6 | (0–10) | 6.16 | 6.79 |

| Pain | 6.2 | 2.2 | (0–10) | 5.95 | 6.46 |

| Fatigue | 6.7 | 2.0 | (0–10) | 6.46 | 6.93 |

| Stress | 6.3 | 2.5 | (0–10) | 6.02 | 6.60 |

| HPQ absolute score | 74.1 | 18.3 | (0–100) | 71.95 | 76.20 |

| HPQ relative score | 1.0 | 0.3 | (0.25–2) | 0.98 | 1.06 |

WLQ: Work Limitations Questionnaire

There were no missing scores from the HPQ as all participants completed all of the items. Both the relative and absolute scores were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Figure 1 shows the distribution of both scores. Both distributions demonstrated deviation from normality (p < 0.0001 for absolute score, p < 0.0001for relative score). The average HPQ absolute score was 74.1% (were 0 is the lowest performance and 100% is the best performance at work in the last 4 weeks), and the average relative score was 1.02 (range is between 0.25 for lowest relative performance and 2 for highest relative performance).

Figure 1.

Histograms of HPQ scores distribution

Construct validity

Results of the hypotheses testing correlations are shown in Table 3 for both the relative and absolute scores. When using the HPQ absolute method of scoring, the HPQ had 4 out of the 7 hypotheses confirmed (57%) indicating moderate construct validity. When using the HPQ relative scoring method of scoring, the HPQ had only one hypothesis confirmed out of the 7 indicating poor construct validity. (See Table 3.)

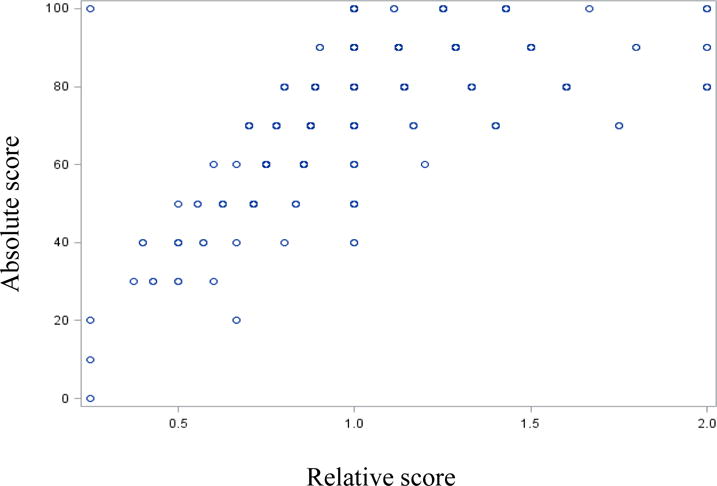

The association between the absolute score and relative score was strong (r=0.64, p < 0.0001). However, the absolute score had more significant associations with previously determined risk factors of work disability. Figure 2 shows a scatter plot of the correlation of the two scoring methods. The exploratory regression analysis revealed superiority of the absolute scoring method over the relative scoring method, as the R2 was 0.103 versus 0.336, respectively. (See Table 4) This supports the findings about the differences construct validity of the HPQ of the two scoring methods using the COSMIN guidelines as well.

Figure 2.

Scatter plot of relative score to absolute score of the HPQ

Table 4.

Exploring scoring methods through regression

| Parameter (N=287) | HPQ relative scoring method R2 = 0.1039 |

HPQ absolute scoring method R2 = 0.3359 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter estimate | P-value | Confidence interval | Parameter estimate | P-value | Confidence interval | |

| Age | 0.002 | 0.231 | (−0.001, 0.005) | 0.249 | 0.005* | (0.073, 0.423) |

| WLQ | −0.00377 | 0.0006* | (−0.005, −0.002) | −0.307 | <.0001* | (−0.410,−0.204) |

| Education | −0.05039 | 0.104 | (−0.111, 0.011) | −3.353 | 0.025* | (−6.281, −0.424) |

| HAQ | −0.02709 | 0.466 | (−0.100, 0.046) | −0.839 | 0.639 | (−4.352, 2.674) |

| Job type | −0.00847 | 0.844 | (−0.093, 0.076) | 1.332 | 0.521 | (−2.755, 5.421) |

| Pain | −0.00697 | 0.541 | (−0.029, 0.015) | −0.155 | 0.776 | (1.232, 0.921) |

| Self-efficacy | −0.01885 | 0.457 | (−0.069, 0.031) | 2.935 | 0.016* | (0.537, 5.332) |

| Job hours | 0.00144 | 0.290 | (−0.001, 0.004) | −0.03550 | 0.588 | (−0.164, 0.093) |

significant at the 0.05 alpha level

Discussion

This study explored the construct validity of the HPQ among people with arthritis and other rheumatological conditions. The hypotheses tested to evaluate construct validity showed variation in the HPQ’s ability to measure work performance when using the two scoring methods; the absolute scoring method had moderate construct validity while the relative scoring method had weak construct validity. Since the absolute scoring method is obtained from one item only, it could be appealing for researchers and clinicians to use in future research.

The correlation between the HPQ absolute score and the WLQ score is moderate, whereas we expected a higher correlation. This could be due to the fact that the HPQ items are about rating the participants’ performance in the workplace in general while the WLQ questions the persons’ limitations in the workplace due to physical health or any emotional problems specifically. Moreover, the HPQ uses a longer recall period: the participant is asked about his/her performance over the past month while the WLQ uses two weeks(7). Another explanation could be that the HPQ might be a more generic assessment of work functioning using a “one global item” to assess work functioning, versus the WLQ which has 5 items.

The magnitude of some correlations, such as those with physical function and age, were weaker than expected for both the absolute and relative scores of the HPQ. A possible explanation maybe, that while these variables are identified as risk factors of work cessation, they are not necessarily risk factors for limitation in work performance. Also, the scores from this sample had smaller correlations with the other measure of work functioning (WLQ), this could mean that the sample had unique characteristics. For example, the physical function levels of this sample were better than other samples reported in the literature for participants who have arthritis and are concerned about being employed(18,19). This could also be due to the fact that the validity of the HPQ still needs further examination by testing how it is associated with more instruments which assess work performance as a construct.

The results of this study revealed that absolute scoring of the HPQ may be a better method of measuring work functioning than the relative scoring approach. Scores from asking participants directly about how they performed at work (i.e. absolute scoring method) were more closely aligned with the proposed hypotheses. The absolute score had a higher magnitude and number of significant correlations including variables of a psychological nature. Self-efficacy, stress, and job satisfaction may be more correlated with the absolute score than the relative one because participants may find it challenging to compare their work functioning relative to others. Also, asking about how others perform in the workplace may not be related to the measurement of work functioning as a construct, as it introduces a dimension that is not directly related to how the person completes his/her tasks at work.

Previous research has shown that the HPQ demonstrates good construct validity and test-retest reliability when compared to actual employer reports of work functioning. A number of studies have used the HPQ successfully in populations with specific health conditions such as workers with migraine, depression and mental health problems. This study showed that the HPQ could also be used to ascertain work outcomes among people with arthritis through exploring its’ construct validity(4,5). Since evaluating construct validity of is an ongoing process, this study initiated the process of ascertaining the validity the HPQ as a measure of work functioning among people with arthritis and other rheumatological conditions. However, further investigation is needed to examine psychometric properties of the HPQ for people with arthritis and rheumatological conditions such as reliability (i.e. test-retest) and responsiveness.

There are a number of limitations for this study. First, only a subscale of the HPQ was administered which could have an impact on the overall scale and the results may not be generalizable to the full scale. Second, the measurement of work performance and all other variables in the study are based on self-report, which could introduce some bias. However, Kessler et al. reported that errors in self-report of work functioning are rather minimal based on a calibration study between the self-report of work functioning and records of payroll and archival performance which showed good concordance(29). Third, the sample recruited for this study had some unique characteristics such as being highly educated and reported higher physical function compared to other work disability intervention studies and may not be generalizable. Also the participants volunteered for the study and findings may not be generalizable to all workers who have arthritis or rheumatic conditions.

Nonetheless, this study provided some the initial steps in establishing construct validity of the work functioning subscale of the HPQ among people with arthritis and other rheumatological conditions. We found evidence of moderate construct validity using the absolute scoring method. However, further research is needed to explore construct validity of the HPQ as a whole instrument using more diverse samples especially people who report actual work functioning restrictions (rather than reporting concerns only). In addition, other psychometric properties such as responsiveness and test-retest reliability of the HPQ still need to be investigated.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: The authors’ work is supported by the following grants:

#H133B100003 from the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research

#P60 AR047785 from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

# H133P120001 National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR) Advanced Rehabilitation Research Training Fellowship.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None declared for all authors.

Contributor Information

Rawan AlHeresh, Assistant Professor, Department of Occupational Therapy, MGH Institute of Health Professions School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Boston, MA.

Michael P. LaValley, Professor, Department of Biostatistics, Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, MA.

Wendy Coster, Professor, Department of Occupational Therapy, Boston University Sargent College of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Boston, MA.

Julie J. Keysor, Associate Professor, Department of Physical Therapy and Athletic Training, Boston University Sargent College of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Boston, MA.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. International classification of functioning disability and health (ICF) 2001 (Journal Article) [Google Scholar]

- 2.AlHeresh RA, Keysor JJ. The Work Activity and Participation Outcomes Framework: a new look at work disability outcomes through the lens of the ICF. Int J Rehabil Res. 2015 Jun;38(2):107–12. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0000000000000112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.AlHeresh R, Vaughan M, LaValley MP, Coster W, Keysor JJ. Critical appraisal of the quality of literature evaluating psychometric properties of arthritis work outcome assessments: A systematic review. Arthritis care & research [Internet] 2015 doi: 10.1002/acr.22814. [cited 2016 Feb 22]; Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.22814/abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Suzuki T, Miyaki K, Song Y, Tsutsumi A, Kawakami N, Shimazu A, et al. Relationship between sickness presenteeism (WHO–HPQ) with depression and sickness absence due to mental disease in a cohort of Japanese workers. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2015 Jul 15;180:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suzuki T, Miyaki K, Sasaki Y, Song Y, Tsutsumi A, Kawakami N, et al. Optimal Cutoff Values of WHO-HPQ Presenteeism Scores by ROC Analysis for Preventing Mental Sickness Absence in Japanese Prospective Cohort. PLoS ONE. 2014 Oct 23;9(10):e111191. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler RC, Ames M, Hymel PA, Loeppke R, McKenas DK, Richling DE, et al. Using the World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ) to evaluate the indirect workplace costs of illness. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2004;46(6):S23–37. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000126683.75201.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lerner D, Amick BC, Rogers WH, Malspeis S, Bungay K, Cynn D. The work limitations questionnaire. MedCare. 2001;39(1):72–85. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200101000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Quality of Life Research. 2010;19(4):539–49. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9606-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Croon EM, Sluiter JK, Nijssen TF, Dijkmans BAC, Lankhorst GJ, Frings-Dresen MHW. Predictive factors of work disability in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2004;63(11):1362–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.020115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allaire S, Wolfe F, Niu J, LaValley MP, Zhang B, Reisine S. Current risk factors for work disability associated with rheumatoid arthritis: Recent data from a US national cohort. Arthritis Care & Research. 2009;61(3):321–8. doi: 10.1002/art.24281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lacaille D, Sheps S, Spinelli JJ, Chalmers A, Esdaile JM. Identification of modifiable work-related factors that influence the risk of work disability in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care & Research. 2004;51(5):843–52. doi: 10.1002/art.20690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bansback N, Zhang W, Walsh D, Kiely P, Williams R, Guh D, et al. Factors associated with absenteeism, presenteeism and activity impairment in patients in the first years of RA. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012 Feb;51(2):375–84. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tillett W, Shaddick G, Askari A, Cooper A, Creamer P, Clunie G, et al. Factors influencing work disability in psoriatic arthritis: first results from a large UK multicentre study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015 Jan;54(1):157–62. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kennedy M, Papneja A, Thavaneswaran A, Chandran V, Gladman DD. Prevalence and predictors of reduced work productivity in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014 Jun;32(3):342–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agaliotis M, Fransen M, Bridgett L, Nairn L, Votrubec M, Jan S, et al. Risk factors associated with reduced work productivity among people with chronic knee pain. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2013 Sep;21(9):1160–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keysor JJ, AlHeresh R, Vaughan M, LaValley MP, Allaire S. The Work-It Study for people with arthritis: Study protocol and baseline sample characteristics. Work. 2016 Jun 14;54(2):473–80. doi: 10.3233/WOR-162331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lerner D, Reed JI, Massarotti E, Wester LM, Burke TA. The Work Limitations Questionnaire’s validity and reliability among patients with osteoarthritis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(2):197–208. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00424-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allaire SH, Li W, LaValley MP. Reduction of job loss in persons with rheumatic diseases receiving vocational rehabilitation: A randomized controlled trial. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2003;48(11):3212–8. doi: 10.1002/art.11256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allaire SH, Jingbo Niu, LaValley MP. Employment and Satisfaction Outcomes From a Job Retention Intervention Delivered to Persons with Chronic Diseases. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin. 2005;48(2):100–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawker GA, Mian S, Kendzerska T, French M. Measures of adult pain: Visual Analog Scale for Pain (VAS Pain), Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS Pain), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPGS), Short Form-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS), and Measure of Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain (ICOAP) Arthritis Care Res. 2011 Nov 1;63(S11):S240–52. doi: 10.1002/acr.20543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fries JF, Spitz PW, Young DY. The dimensions of health outcomes: the health assessment questionnaire, disability and pain scales. J Rheumatol. 1982;9(5):789–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) System [Internet] [cited cited 2015 May 4]. Available from: http://www.bls.gov/soc/

- 23.COSMIN checklist manual [Internet] [cited 2017 Mar 21]. Available from: http://scholar.googleusercontent.com/scholar?q=cache:OLT-07z8gh8J:scholar.google.com/+Mokkink+LB,+Terwee+CB,+Patrick+DL,+Alonso+J,+Stratford+PW,+Knol+DL,+et+al.+The+COSMIN+checklist+manual&hl=en&as_sdt=0,22.

- 24.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112(1):155–9. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Theis KA, Murphy L, Hootman JM, Helmick CG, Yelin E. Prevalence and correlates of arthritis-attributable work limitation in the US population among persons ages 18–64: 2002 National Health Interview Survey Data. Arthritis & Rheumatism-Arthritis Care & Research. 2007;57(3):355–63. doi: 10.1002/art.22622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yelin E. Work disability in rheumatic diseases. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007;19(2):91–6. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3280126b66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pincus T, Swearingen C, Wolfe F. Toward a multidimensional Health Assessment Questionnaire (MDHAQ): assessment of advanced activities of daily living and psychological status in the patient-friendly health assessment questionnaire format. Arthritis Rheum. 1999 Oct;42(10):2220–30. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199910)42:10<2220::AID-ANR26>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Portney L, Watkins M. Appleton & Lange. 2000. Foundations of clinical research: applications to practice (ed) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kessler RC, Barber C, Beck A, Berglund P, Cleary PD, McKenas D, et al. The world health organization health and work performance questionnaire (HPQ) Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2003;45(2):156–74. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000052967.43131.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]