Abstract

Background

The abnormal biological activity of cytokines plays an important role in the pathophysiology of both systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). Several studies have highlighted the association of vitamin D and certain pro-inflammatory cytokines with disease activity in SLE. However, there are limited data on the association of vitamin D and antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) with various proinflammatory biomarkers in these patients and their relative impact on clinical outcomes.

Methods

The serum levels of several aPL, 25-hydroxy vitamin D, pro-inflammatory cytokines including IFNα, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IP10, sCD40L, TNFα and VEGF were measured in 312 SLE patients from the Jamaican (n-=45) and Hopkins (n=267) Lupus cohorts using commercial Milliplex and ELISA assays. Oxidized LDL/β2glycoprotein antigenic complexes (oxLβ2Ag) and their associated antibodies were also measured in the Jamaican cohort. Healthy controls for oxidative marker and cytokine testing were utilized.

Results

Abnormally low vitamin D levels were present in 61.4% and 73.3% of Hopkins and Jamaican SLE patients respectively. Median concentrations of IP10, TNFα, sCD40L and VEGF were elevated in both cohorts, oxLβ2Ag and IL-6 were elevated in the Jamaican cohort and IFNα, IL-1β and IL-8 were the same or lower in both cohorts compared to controls. IP10 and VEGF were independent predictors of disease activity, aPL, IP10 and IL-6 were independent predictors of thrombosis and IL-8 and low vitamin D were independent predictors of pregnancy morbidity despite there being no association of vitamin D with pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that aPL-mediated pro-inflammatory cytokine production is likely a major mechanism of thrombus development in SLE patients. We provide presumptive evidence of the role IL-8 and hypovitaminosis D play in obstetric pathology in SLE but further studies are required to characterize the subtle complexities of vitamin D’s relationship with cytokine production and disease activity in these patients.

INTRODUCTION

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a prototypic systemic autoimmune disease, which affects millions of persons worldwide and directly targets multiple organ systems resulting in protean clinical manifestations (1). Antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL), the serological hallmark of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), are found in approximately 30–40% of patients with SLE and approximately 50% of those patients fulfill criteria to be classified as having secondary APS (2). Abnormal biological activity of cytokines plays an important role in the pathophysiology of both SLE and APS and several studies have highlighted the association of certain pro-inflammatory cytokines with disease activity in SLE. These cytokines include interferon-alpha (IFNα), interferon-inducible protein 10 (IP10), tumor necrosis factorα (TNFα), soluble CD40 ligand (sCD40L) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) (3, 4).

Tissue factor (TF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) have been shown to be upregulated in endothelial cells and monocytes from patients with APS and they appear to be associated with a prothrombotic phenotype observed in these patients (5). Also, IL-1, IL-6 and IL-8 have been shown to be upregulated by endothelial cells treated with IgG and IgM aPL antibodies in vitro (6) and TNFα was shown to be one of the cytokines involved in aPL-mediated pregnancy morbidity in mouse models (7).

Vitamin D primarily plays an important role in bone health and calcium homeostasis but recent evidence has highlighted its potent immunomodulatory properties. Vitamin D may act by suppressing T cell proliferation, monocyte differentiation, dendritic cell proliferation and activation, and MHCII expression on macrophages. Vitamin D also suppresses production of antibodies and certain proinflammatory cytokines (8). A high prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency and deficiency has been demonstrated in SLE patients, which has been attributed to avoidance of sun exposure, glucocorticoid use and renal disease (9–11). An increase in serum vitamin D levels has now been shown to help SLE activity in both a cohort study (12) and a randomized clinical trial (13). Similarly, vitamin D insufficiency is more prevalent in APS patients compared to normal controls and furthermore, abnormally low vitamin D levels correlate with thrombosis in these patients (14). However, there are limited data on the association of vitamin D levels with various proinflammatory biomarkers in patients with SLE and APS and their relative clinical impact. As such, we sought to determine the role of serum vitamin D, various aPL as well as proinflammatory cytokines, including IFNα, IP10, TNFα, sCD40L, VEGF, IL-1, IL-8 and IL-6 as markers of disease activity and thrombotic and obstetric clinical outcomes in patients with SLE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Characteristics of Study Population

Serum samples were obtained from 312 patients from two independent SLE cohorts: the Hopkins Lupus Cohort (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) (n=267, 94.4% female, mean age 47.6±12.4, range 19–81) and the Jamaican SLE cohort (University of the West Indies, Mona, Kingston, Jamaica) (n=45, 97.8% female, mean age 44.0±12.1, range 25–73). The Hopkins Lupus Cohort is a longitudinal study of lupus activity, organ damage, and quality of life in SLE patients. The demographic composition is balanced largely between Caucasian (151/267, 56.6%) and African-American (102/267, 38.2%) SLE patients. The Jamaican SLE cohort is a longitudinal study of disease activity in SLE patients routinely evaluated at the University of the West Indies, Mona in Kingston, Jamaica. The majority of patients in the Jamaican SLE cohort are of Afro-Caribbean descent (43/45, 95.6%).

Patients for whom disease activity measures were available were included in the study if serum samples stored at −20°C were available for testing. The samples used in this study were taken from cohort storage repositories and as such, several samples were previously unfrozen at least once before. Disease activity was measured by the SELENA-SLEDAI score and the physician global assessment score (PGA) in the Hopkins cohort and the BILAG index score in the Jamaican cohort. Patients eligible for inclusion in the study were classified into 3 categories based on results of 25-hydroxy-vitamin D testing, such that normal vitamin D levels were defined as being above 30 ng/mL, vitamin D insufficiency as levels between 20–30 ng/ml and vitamin D deficiency as levels below 20 ng/ml. Patients that, at the time of testing, were receiving immunosuppressants such as azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenalate mofetil or prednisone doses above 10mg daily were excluded as these agents may affect cytokine levels. Similarly, patients that had significant renal disease defined as a glomerular filtration rate of less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, which may affect vitamin D levels, were also excluded (15).

Serum samples from healthy patients with no evidence of inflammatory disease were included in the study as controls for cytokine testing (n=30, 83.3% female, mean age 43.5±12.5, range18–65] and as controls for oxidative biomarker testing (n=51, 45.1% female, mean age 49.4±11.0, range 26–76). These sera were obtained from healthy individuals evaluated at the Antiphospholipid Standardization Laboratory, University of Texas Medical Branch. The Institutional Review Boards from the respective institutions approved the use of samples and clinical data from all patients. For each patient, the same sample was used in all in-vitro assays and all testing was performed at the Antiphospholipid Standardization Laboratory, University of Texas Medical Branch. This study was conducted following the declaration of Helsinki guidelines for inclusion of humans in research. All subjects provided informed consent.

Characteristics of Antiphospholipid antibody test

Anticardiolipin (aCL) antibodies (IgG, IgM and IgA) were evaluated using an in-house ELISA method as previously described (16). IgG, IgM and IgA anti-β2GPI antibodies were determined using the commercial QUANTA Lite® anti-β2GPI assay (INOVA Diagnostics, San Diego CA, USA). All assays were performed manually according to the manufacturer’s instructions and were considered positive when titers were above their pre-established cut off points.

Oxidative Marker Testing

Markers of oxidative stress including IgG anti-oxidized low-density lipoprotein/β2glycoprotein I antibodies (a-oxLβ2Ab) and oxidized low-density lipoprotein/β2-glycoprotein I antigen complex (oxLβ2Ag) were both measured using commercially available ELISA kits [Corgenix, Broomfield, CO, USA] in serum samples from the Jamaican cohort of patients. Positive IgG a-oxLβ2Ab titers were defined by the manufacturer as greater than 19 G units. Serum samples from the control group of healthy individuals were used to determine normal levels of oxLβ2Ag, which were defined as the 99th percentile of the concentrations obtained in the control group.

Cytokine Testing

The MILLIPLEXMAP human cytokine/chemokine panel assay (Millipore, Billerica, MA), which utilizes Luminex xMAP technology, was used to determine serum levels of the cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNFα, IFNα, IP10, VEGF and sCD40L as described previously (17). Briefly, 25μL of patient serum or plasma was incubated with color-coded bead sets, each being specific for one of the analytes being tested. A biotinylated detection antibody was then introduced followed by incubation with streptavidin-phycoerythrin, which acted as the reporter molecule on the surface of each microsphere. To determine the number/percentage of SLE patient samples elevated for each cytokine, we defined a cut-off value as the 99th percentile of the concentrations obtained in the control sera.

Vitamin D Testing

Total serum concentrations of 25-hydroxy-vitamin D (25-OH VD) were determined using a commercially available ELISA assay utilizing competitive inhibition of labeled vitamin D standards (Eagle Biosciences, Nashua, NH, USA).

Statistical Analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± SD or median with the corresponding interquartile range. Vitamin D levels across seasons and cytokine and oxidative marker levels across cohort and control groups were evaluated using one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc analysis or the Kruskal Wallis test with post-hoc multiple pairwise comparisons using the Steel-Dwass-Critchlow-Fligner procedure as required. Univariate association between continuous variables were done using Pearson correlation and between dichotomous variables using Pearson chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. For multivariate analysis, a forward stepwise linear regression model and forward stepwise logistic regression model were used for continuous and dichotomous response variables respectively. The analysis was performed using the xlstat software, Version 16.6 (Addinsoft, NY, United States) and results were considered statistically significant if p values were less than 0.05 (p<0.05).

RESULTS

Patient Demographics and Clinical Data

Table 1 summarizes the baseline demographic and prevalence of APS and SLE related clinical features of the study population and controls. APS-related manifestations occurred 2 to 8 times more frequently in the Hopkins cohort compared to the Jamaican SLE cohort. While the difference in the frequency of arterial thrombosis between the 2 cohorts achieved statistical significance, the other comparisons of APS-related manifestations only approached statistical significance. However, the prevalence of aPL positivity, both at cut-off and at APS classification criteria levels, were similar in both cohorts as was the prevalence of SLE criteria manifestations. Interestingly, the mean duration of disease was over 15 years in the Hopkins cohort, almost 3 times as that in the Jamaican lupus cohort. Both Hopkins and Jamaican SLE patients included in the study were treated with hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) and/or low dose prednisone, however, HCQ was used more frequently in the Hopkins cohort while prednisone was most commonly utilized in the Jamaican cohort. The cytokine and oxidative biomarker control patients had no APS-related clinical manifestations and were all aPL negative.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of patients in the SLE cohorts and control groups

| Demographic and Clinical Characteristics |

Hopkins Cohort (n=267) |

Jamaican Cohort (n=46) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Mean±SD) | 47.6±12.9 | 44.0±12.1 | 0.073 |

| [Range] | [19–81] | [25–73] | |

| Female (%) | 252/267 (94.4) | 44/45 (97.8) | 0.341 |

| PE/E (%) | 23/252 (9.1) | 1/44 (2.3) | 0.100 |

| Miscarriage (%) | 78/252 (31.0) | 2/44 (4.5) | 0.088 |

| Venous Thrombosis (%) | 51/267 (19.1) | 2/45 (4.4) | 0.097 |

| Arterial Thrombosis (%) | 50/267 (18.7) | 4/45 (8.9) | 0.017 |

| aCL G1 (%) | 38/267 (14.2) | 2/45 (4.4) | 0.070 |

| aCL G Criteria2 (%) | 14/267 (5.2) | 2/45 (4.4) | 0.823 |

| aCL M (%) | 30/267 (11.2) | 4/45 (8.9) | 0.641 |

| aCL M Criteria (%) | 7/267 (2.6) | 1/45 (2.2) | 0.876 |

| aCL A (%) | 7/267 (2.6) | 0/45 (0.0) | 0.876 |

| aCL A Criteria (%) | 4/267 (1.5) | 0/45 (0.0) | 0.722 |

| aβ2 G (%) | 13/267 (4.8) | 1/45 (2.2) | 0.429 |

| aβ2 G Criteria (%) | 8/267 (3.0) | 1/45 (2.2) | 0.775 |

| aβ2 M (%) | 12/267 (4.5) | 1/45 (2.2) | 0.482 |

| aβ2 M Criteria (%) | 8/267 (3.0) | 0/45 (0.0) | 0.775 |

| aβ2 A (%) | 32/267 (12.0) | 4/45 (8.9) | 0.549 |

| aβ2 A Criteria (%) | 15/267 (5.6) | 2/45 (4.4) | 0.749 |

| Any aPL (%) | 73/267 (27.3) | 14/45 (31.1) | 0.603 |

| Any aPL Criteria (%) | 27/267 (10.1) | 5/45 (11.1) | 0.531 |

| Mucocutaneous3 (%) | 214/267 (80.1) | 33/45 (73.3) | 0.299 |

| Neurological3 (%) | 26/267 (9.7) | 7/45 (15.6) | 0.242 |

| Musculoskeletal3 (%) | 258/267 (96.6) | 43/45 (95.6) | 0.719 |

| Renal3 (%) | 52/267 (19.5) | 7/45 (15.6) | 0.536 |

| HCQ | 232/267 (86.9) | 29/45 (64.4) | 0.001 |

| Prednisone4 | 77/267 (28.8) | 30/45 (66.7) | <0.0001 |

| Dx Duration (Mean±SD) | 202.5±128.9 | 81.6±60.6 | |

| [Range]5 | [7–621] | [6–288] | <0.0001 |

The prevalence of aPL positivity was considered at assay cut-off1 or at APS classification criteria levels2. These manifestations3 were identified as present if the parameters of the particular SLE ACR classification criteria were met. All patients that were being treated with prednisone4 were taking low doses (less than 10mg daily). Disease (Dx) duration5 was measured in months from Dx onset to sample collection date. aCL – anticardiolipin IgG or IgM or IgA, aβ2 – anti-beta 2 glycoprotein I IgG or IgM or IgA, HCQ – hydroxychloroquine, PE/E – Pre-eclampsia/eclampsia

Proinflammatory Cytokines and Oxidative Markers

As shown in table 2, median serum concentrations of TNFα, IP10, sCD40L AND VEGF were significantly elevated in both SLE cohorts compared to the control population. Interestingly, while median IL-6 levels were higher in the Jamaican SLE cohort compared to controls, there was no statistical difference between IL-6 levels in the Hopkins Lupus cohort and controls. A total of 2/45 (6.5%) SLE patients in the Jamaican cohort were positive for a-oxLβ2Ab and both these patients were positive for at least one aPL. Median oxLβ2Ag levels were also significantly elevated in the Jamaican cohort compared to controls. Conversely, median levels of IL-1β, IFNα and IL-8 in both cohorts were either significantly less or statistically similar to levels in the control patients.

Table 2.

Comparison of median and interquartile range of cytokine and oxidative biomarker levels in Hopkins and Jamaican SLE cohorts versus healthy controls

| Cytokines | Median

|

IQR

|

Comparison

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JA SLE | Hp SLE | Controls | JA SLE | Hp SLE | Controls | p-value1 | p-value2 | |

|

|

|

|

||||||

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 1.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.9 – 6.3 | 0.0 – 8.4 | 0.1 – 0.1 | < 0.0001 | 0.666 |

| IL-1β (pg/ml) | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0–0.0 | 0.1 – 0.7 | 0.2 – 0.2 | < 0.0001 | 0.538 |

| TNFα (pg/ml) | 7.1 | 6.6 | 0.0 | 4.5 – 12.1 | 3.3 – 11.5 | 0.0–0.0 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| IP10 (pg/ml) | 226.7 | 366.2 | 96.2 | 139.8–437.0 | 213.4 – 611.3 | 66.3 –124.3 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| sCD40L (pg/ml) | 232.3 | 1597.8 | 16.4 | 149.3 – 647.5 | 517.5–6401.2 | 11.3 –25.9 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| IFNα (pg/ml) | 4.5 | 10.1 | 0.9 | 0 – 9.2 | 0.6 – 44.0 | 0.9 – 10.2 | 0.951 | 0.533 |

| IL-8 (pg/ml) | 15.4 | 6.6 | 27.4 | 7.9 – 38.5 | 2.6 – 12.9 | 15.1 – 45.1 | 0.113 | < 0.0001 |

| VEGF (pg/ml) | 164.9 | 173.2 | 88.3 | 99.1 – 352.5 | 95.0 – 312.8 | 60.0 – 145.2 | 0.040 | 0.003 |

| oxLβ2Ag (U/ml) | 14.1 | – | 2.8 | 9.6 – 19.7 | – | 1.1 – 7.0 | < 0.0001 | – |

P-value refers to comparison of median values between Jamaican SLE cohort and controls1 and comparison between Hopkins SLE cohort and controls2 with Kruskal–Wallis test and post-hoc comparisons by Steel-Dwass-Critchlow-Fligner procedure. IFNα – interferon alpha, IL-interleukin, IP10 – interferon-inducible protein 10, IQR – interquartile range, JA– Jamaican, Hp – Hopkins, oxLβ2Ag – oxidized low density lipoprotein beta 2 glycoprotein antigen complex, sCD40L- soluble CD40 ligand, TNFα – tumor necrosis alpha, VEGF – vascular endothelial growth factor

Vitamin D Distribution

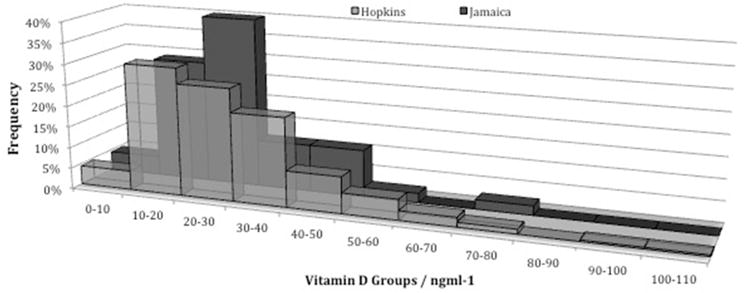

The relative frequency of 25-OH VD concentrations in the 267 SLE patients from the Hopkins cohort and the 45 patients from the Jamaican cohort is shown in figure 1. The mean vitamin D concentration was 27.0± 13.6 (range 7.0 – 78.4) and 28.2 ± 15.0 (range 4.1 – 101.6) ng/ml in the Jamaican and Hopkins lupus cohorts respectively. More than 70% of Jamaican patients had vitamin D serum levels below normal, with 33.3% (15/45) patients being classified as vitamin D deficient and 40.0% (18/45) patients as vitamin D insufficient. Only 26.7% (12/45) Jamaican SLE patients had normal vitamin D levels. Similarly, almost 2/3 of the Hopkins SLE patient population had below normal vitamin D levels, with 34.8% (93/267) classified as vitamin D deficient and 26.6% (71/267) classified as vitamin D insufficient. There was no statistically significant difference in vitamin D levels between the 2 cohorts (p=0.613).

Figure 1.

Vitamin D levels below 20ng/ml and levels between 20 to 30ng/ml are defined as vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency respectively. Abnormal vitamin D levels occurred in more than 60% of patients in the Hopkins cohort and more than 70% of patients in the Jamaican cohort.

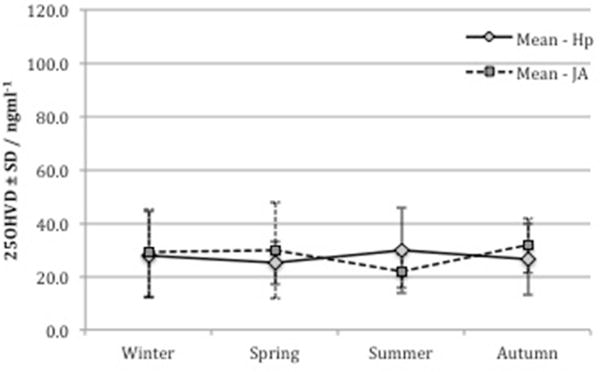

In order to determine the effect of seasonal variation on vitamin D levels in both cohorts we assessed the monthly variation in mean 25OH vitamin D levels. Samples were grouped into 4 categories based on collection dates – winter (Jan–Mar), spring (Apr–May), summer (Jun–Sep) and autumn (Oct–Dec). As shown in figure 2, the variation of mean 25OH-vitamin D levels by season was not statistically significant.

Figure 2.

The seasonal variation of mean vitamin D levels was not significant in either cohort by one-way ANOVA, p=0.438 and 0.356 in the Jamaican and Hopkins cohorts respectively. Hp- Hopkins, JA- Jamaican

Biomarker Associations

Table 3 shows the correlation of aPL, oxidative markers, pro-inflammatory cytokines and 25-OH VD levels. Unsurprisingly, there was good to excellent agreement (r >0.80) among TNFα, IL-6 and IL-1β levels in both cohorts. Similarly, there was overall moderate to good agreement between these 3 cytokines and other pro-inflammatory cytokines IFNα, IL-8 and VEGF (r0.40 – 0.80). In both cohorts, the correlation between aPL was generally fair to moderate, the highest values occurring between aPL of the same isotype. In the Jamaican cohort, IgG a-oxLβ2Ab had excellent to almost perfect correlation with IgG aCL (r0.86, p<0.0001) and IgG anti-β2GPI (r0.98, p<0.0001). In the Hopkins cohort, there was no significant correlation between 25-OH VD levels and any aPL or pro-inflammatory biomarkers. In the Jamaican cohort however, there was a moderately strong positive association of 25-OH VD with oxLβ2Ag (r0.50, p=0.0006) but vitamin D levels were not associated with any pro-inflammatory cytokine.

Table 3.

Correlation of serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, oxidative markers, antiphospholipid antibodies and vitamin D in Hopkins and Jamaican SLE cohorts

| Comparisons (Jamaica) | Correlation | Comparisons (Hopkins) | Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excellent Agreement | |||

| aβ2G_aOXLβ2Ab | 0.98** | IL1B_TNFα | 0.94** |

| IL6_TNFα | 0.91** | IL1B_IL6 | 0.88** |

| aβ2G_aCLG | 0.89** | IL6_TNFα | 0.86** |

| IL1B_IL6 | 0.88** | aβ2G_aCLG | 0.82** |

| aCLG_aOXLβ2Ab | 0.86** | aβ2M_aCLM | 0.80** |

| TNFα_VEGF | 0.84** | ||

| IFNα_IL6 | 0.83** | ||

| IL8_TNFα | 0.82** | ||

| Moderate to Good Agreement | |||

| IL1β_TNFα | 0.78** | IL1β_TNFα | 0.72** |

| IL8_IFNα | 0.76** | aβ2G_aCLA | 0.71** |

| IL1β_sCD40L | 0.71** | aβ2A_aCLA | 0.65** |

| IL6_VEGF | 0.67** | aβ2A_aB2G | 0.63** |

| IFNα_IL1β | 0.67** | Score_PGA | 0.63** |

| IFNα_TNFα | 0.66** | IL6_IL8 | 0.61** |

| IL1β_IL8 | 0.60** | IL1β_IL8 | 0.60** |

| IL8_VEGF | 0.58** | aCLA_aCLG | 0.58** |

| IL1β_VEGF | 0.57** | aβ2A_aCLG | 0.56** |

| oxLβ2Ag_VD | 0.50** | IFNα_IL6 | 0.54** |

| sCD40L_VEGF | 0.42* | IFNα_IL1β | 0.46** |

| IFNα_VEGF | 0.40* | ||

| Weak Agreement | |||

| aCLA_sCD40L | 0.39* | Score_VEGF | 0.33** |

| aCLM_IFNα | 0.38* | IP10_Score | 0.32** |

| aβ2A_VD | 0.37* | IFNα_Score | 0.24** |

| sCD40L_TNFα | 0.37* | PGA_IP10 | 0.18* |

| IP10_Score | 0.36* | PGA_VEGF | 0.18* |

| aCLM_sCD40L | 0.34* | ||

| IL6_sCD40L | 0.34* | ||

| aβ2A_oxLβ2Ag | 0.31* | ||

Pearson correlation coefficient used to evaluate association. aCL- anticardiolipin, aβ2 – anti-beta2 glycoprotein I, aOXLβ2Ab – antioxidized LDL β2 glycoprotein I, IFNα – interferon alpha, IL-interleukin, IP10 – interferon-inducible protein 10, oxLβ2Ag – oxidized low density lipoprotein beta 2 glycoprotein antigen complex, PGA – physician global assessment score, Score: disease activity score SELENA SLEDAI in Hopkins cohort and BILAG in Jamaican cohort, sCD40L– soluble CD40 ligand, TNFα – tumor necrosis alpha, VD –25- hydroxy vitamin D, VEGF – vascular endothelial growth factor.

p<0.05,

p<0.001.

Disease Activity

In the Hopkins cohort, SELENA-SLEDAI and PGA were used as measures of disease activity and correlation with proinflammatory biomarkers is shown in Table 3. The mean SELENA-SLEDAI score was 2.2 ± 3.2 (range 0 – 25.2) and a total of 27/267 (10.1%) patients had a clinically significant score (≥6.0). Unsurprisingly, the SELENA SLEDAI score had a moderately strong association with the physician global assessment score (PGA) (r0.63, p <0.0001). The SELENA-SLEDAI score was also significantly associated, albeit relatively weakly, with the cytokines IP10 (0.32, p<0.0001), IFNα (r0.24, p<0.0001) and VEGF (r0.33, p<0.0001) as well as IgA anti-β2GPI (r0.13, p=0.034). The PGA itself was significantly associated with IP10 (r0.18, p<0.001) and VEGF (r0.18, p<0.001) levels as well. In multivariate linear regression analysis only the association of SELENA-SLEDAI with VEGF (p<0.0001) and IP10 (p<0.0001) remained statistically significant, with a total R2 of 0.171 indicating a relatively weak relationship.

In the Jamaican Lupus cohort, the BILAG index was the instrument used to measure disease activity and correlations are also shown in table 3. The mean BILAG index score was 2.7 ± 1.9 (range 1 – 9) and a total of 13/46 (28.2%) had moderate disease activity level (grade B) in at least one organ system, none had severe activity (grade A). The only significant association with the BILAG index occurred with the cytokine IP10 (r0.36, p=0.016), which maintained significance in multivariate linear regression analysis (R2 = 0.13, p=0.016) (Table 3).

Thrombosis

The univariate association of the various pro-inflammatory biomarkers with APS-related clinical manifestations is summarized in table 4. In the Hopkins cohort, venous thrombosis was significantly associated with several aPL in univariate analyses including aCL IgG, aCL IgA, anti-β2GPI IgG and anti-β2GPI IgA (OR ranging from 4.0 – 28.7, p<0.0001), as well as elevated IP10 (OR 2.7, 95%CI 1.3–5.7, p=0.010), IL-8 (OR 4.4, 95%CI 1.0–20.2, p=0.050) and VEGF (OR 2.0, 95%CI 1.0–3.8, p=0.047). Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that only antiβ2GPI IgG (OR 6.5 95%CI 1.6–26.3, p=0.009) and anti-β2GPI IgA (OR 3.2 95%CI 1.2–8.2, p=0.016) remained significantly associated with venous thrombosis. In the Jamaican cohort, aCL IgG (OR 42.0, 95%CI 2.6–682.5) and aCL IgM (OR13.3, 95%CI 1.1–164.5) were also associated with venous thrombosis (table 4), however, these did not remain statistically significant in multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Table 4.

Univariate association of pro-inflammatory cytokines, oxidative markers, antiphospholipid antibodies and vitamin D with APS-related clinical manifestations expressed as odds ratios with 95% confidence Intervals

| Marker | Hopkins Cohort | Jamaican Cohort | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| VT | AT | PE/E | Misc | VT | AT | PE/E | Misc | |

| aCL G | 4.0 (1.9–8.4)** | 1.4 (0.6–3.2) | 1.9 (0.7–5.4) | 1.5 (0.7–3.1) | 42.0 (2.6–682.5)** | 13.3(1.1–164.5)* | 4.0 (0.1–116.3) | 2.3 (0.1–58.3) |

| aCL M | 0.8 (0.3–2.2) | 0.6 (0.2–1.8) | 0.7 (0.2–2.9) | 1.5 (0.7–3.4) | 13.3 (1.1–164.5)* | 4.2 (0.5–38.2) | 3.0 (0.1–85.1) | 1.8 (0.1–42.6) |

| aCL A | 28.7 (4.7–174.1)** | 0.7 (0.1–4.3) | 2.0 (0.3–13.0) | 0.4 (0.1–3.0) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| aβ2 G | 11.3 (3.5–36.6)** | 1.3 (0.4–4.6) | 2.3 (0.5–10.0) | 0.2 (0.0–1.2) | 2.2 (0.3–17.6) | 3.1 (0.1–87.2) | 9.7(0.3–350.5) | 5.7 (0.2–177.7) |

| aβ2 M | 0.8 (0.2–3.5) | 1.5 (0.4–5.2) | 1.1 (0.2–6.6) | 0.5 (0.1–2.3) | 2.2 (0.3–17.6) | 3.1 (0.1–87.2) | 9.7(0.3–350.5) | 5.7 (0.2–177.7) |

| aβ2 A | 5.7 (2.6–12.3)** | 2.2 (1.0–5.0)* | 1.8 (0.6–5.4) | 0.9 (0.4–2.1) | 0.4 (0.1–3.0) | 4.2 (0.5–38.2) | 3.0 (0.1–85.1) | 1.8 (0.1–42.6) |

| Low VD | 1.7 (0.9–3.2) | 1.4 (0.7–2.7) | 4.4 (1.4–14.1)* | 1.4 (0.8–2.4) | 0.3 (0.0–3.6) | 4.1 (0.2–82.1) | 1.3 (0.1–33.6) | 0.4 (0.0–3.8) |

| IL-6 | 1.4 (0.7–2.6) | 3.0 (1.6–5.7)** | 0.3 (0.1–1.1) | 1.5 (0.9–2.7) | 0.1 (0.0–1.1) | 0.3 (0.0–5.4) | 0.9 (0.0–22.7) | 0.5 (0.0–11.3) |

| IL-1β | 0.5 (0.2–1.2) | 1.4 (0.7–2.9) | 0.4 (0.1–1.3) | 0.6 (0.3–1.1) | 1.8 (0.1–43.6) | 1.0 (0.0–20.7) | 3.0 (0.1–85.1) | 1.8 (0.1–42.6) |

| TNFα | 1.2 (0.6–2.2) | 2.5 (1.3–4.6)* | 1.0 (0.4–2.4) | 1.4 (0.8–2.3) | 0.3 (0.0–6.9) | 0.5 (0.1–4.3) | 0.5 (0.0–13.6) | 0.3 (0.0–6.7) |

| IP10 | 2.7 (1.3–5.7)* | 3.1 (1.4–6.7)* | 1.2 (0.5–2.9) | 1.4 (0.8–2.3) | 0.3 (0.0–5.8) | 0.4 (0.1–3.5) | 4.3 (0.2–111.4) | 0.3 (0.0–5.5) |

| sCD40L | 0.6 (0.2–1.8) | 1.2 (0.4–4.1) | 19.6(2.7–140.7)* | 1.6 (0.5–4.8) | 1.2 (0.1–26.5) | 0.5 (0.1–4.1) | 0.6 (0.0–16.2) | 0.2 (0.0–1.5) |

| IFNα | 2.3 (0.8–6.2) | 1.3 (0.4–3.8) | 0.6 (0.1–3.4) | 2.1 (0.8–5.5) | 3.4 (0.1–91.6) | 1.8 (0.1–43.7) | 5.7 (0.2–177.7) | 3.3 (0.1–89.5) |

| IL-8 | 4.4 (1.0–20.2)* | 9.3 (1.9–45.3)* | 5.4 (1.1–26.8)* | 1.1 (0.2–5.4) | 3.4 (0.1–91.6) | 1.8 (0.1–43.7) | 5.7 (0.2–177.7) | 3.3 (0.1–89.5) |

| VEGF | 2.0 (1.0–3.8)* | 1.6 (0.8–3.1) | 0.9 (0.3–2.5) | 1.0 (0.5–1.9) | 0.6 (0.0–13.1) | 1.0 (0.1–7.9) | 1.0 (0.0–25.5) | 0.6 (0.0–12.7) |

| a-oxLβ2Ab | – | – | – | – | 2.4 (0.1–59.7) | 1.3 (0.1–28.4) | 4.0 (0.1–116.3) | 2.3 (0.1–58.3) |

| oxLβ2Ag | – | – | – | – | 1.9 (0.1–42.9) | 0.1 (0.0–0.7)* | 1.0 (0.0–27.0) | 0.3 (0.0–3.3) |

All response and explanatory variables were dichotomous: clinical variables were recorded as present or absent, aPL were recorded as positive or negative and cytokines and oxidative markers recorded as elevated above the 99th percentile value for corresponding control population or not elevated. Low vitamin D was defined as a value below 30ng/ml.

N/A – analysis not possible as no SLE patients in the Jamaican cohort were positive for IgA aCL.

p<0.05,

p<0.001.

aCL– anticardiolipin, aβ2 – anti-β2 glycoprotein I, a-oxLβ2Ab – anti-oxidized LDL β2 glycoprotein I, AT – arterial thrombosis, IFNα – interferon alpha, IL-interleukin, IP10 – interferon-inducible protein 10, JA– Jamaican, Low VD – 25 hydroxy vitamin D below 30ng/ml, Misc – miscarriage, oxLβ2Ag – oxidized low density lipoprotein beta 2 glycoprotein antigen complex, PE/E – pre-eclampsia/eclampsia, sCD40L– soluble CD40 ligand, TNFα – tumor necrosis alpha, VEGF – vascular endothelial growth factor, VT – venous thrombosis.

Arterial thrombosis in the Hopkins cohort was significantly associated with anti-β2GPI IgA (OR 2.2 95%CI 1.0–5.0, p=0.050), IL-6 (OR 3.0 95%CI 1.6–5.7, p=0.0005), TNFα (OR 2.5 95%CI 1.3–4.6, p=0.004), IP10 (OR 3.1 95%CI 1.4–6.7), p=0.005) and IL-8 (OR 9.3 95%CI 1.9–45.3, p=0.002). In multivariate analysis, the association with IL-6 (OR 2.2 95%CI 1.1–4.3, p=0.027) and IP10 (OR 2.4 95%CI 1.1–5.6, p=0.039) remained significant. In the Jamaican cohort, aCL IgG was positively associated with arterial thrombosis (OR 13.3, 95%CI 1.1–164.5), while oxLβ2Ag was negatively associated (OR 0.1 95%CI 0.0–0.7, p =0.020). Both aCL IgG (OR 95.7, 95%CI 1.5–626.5, p=0.033) and oxLβ2Ag (OR 0.04, 95%CI 0.01–1.00) p=0.050) remained significant in in multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Pregnancy Morbidity

In the Hopkins cohort, PE/E was significantly associated with low 25-OH VD levels (OR 4.4 95%CI 1.4–14.1, p=0.012), sCD40L (OR 19.6, 95%CI 2.7–140.7, p=0.003) and IL-8 (OR 5.4 95%CI 1.1–26.8, p=0.037). Abnormal vitamin D levels (OR 3.9 95%CI 1.3–11.8, p=0.016) and IL-8 (OR 24.4 95%CI 1.9–317.3, p=0.015) remained significantly associated with PE/E in multivariate analyses. However, there were no significant associations of the various markers with miscarriage in the Hopkins cohort or with miscarriage or PE/E in the Jamaican cohort.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluate the impact of vitamin D, proinflammatory cytokines and aPL on clinical outcomes in two independent SLE cohorts. The distribution of 25-OH VD levels in the Hopkins and Jamaican cohorts were strikingly similar, mean levels in each cohort falling below what is considered the normal reference value of 30ng/ml (18). The observed high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency in these cohorts has been shown in previous studies of both cohorts (12, 19) as well as in other independent studies. It is a common finding that transcends differences in ethnicity (20) and has largely been thought to occur as a result of disease activity limiting nutritional intake and sunlight exposure. It is now widely accepted, however, that the low vitamin D levels seen in SLE patients may also contribute to the pathogenesis of disease, through the resultant decrease in its immunomodulatory effect, rather than occurring as an epiphenomenon (20).

We confirm the presence of several pro-inflammatory cytokines including IP10, IL-6, VEGF, TNFα and sCD40L in elevated concentrations in SLE patients compared to healthy controls. These findings were largely consistent in both cohorts and are in keeping with previous studies (21–23). The cytokines IP10, sCD40L and TNFα are important mediators of B and T lymphocyte activation, inflammation and autoantibody production in SLE and the consistent elevation of these cytokines is likely a reflection of the central importance of these immune processes in SLE pathogenesis (24). Similarly, VEGF is of paramount importance in the development of vascular pathology in SLE patients and is a useful biomarker for detecting systemic involvement in these patients (5). Most previous clinical studies have also failed to demonstrate elevations of IL-1β and IL-8 levels in SLE patients compared to controls, although studies in mice have highlighted the importance of IL-1β in the pathogenesis of experimental SLE (25).

The higher level of IFNα in our SLE cohorts compared to controls was not statistically significant and this was somewhat surprising given the central importance of this cytokine and, more generally, the IFN-gene signature in SLE and APS pathogenesis (21, 26). The reason for this paradoxical finding is unclear but could possibly be due to differences in the levels of IFNα in clinical subgroups of SLE patients. Despite this however, the IFN-driven cytokine IP10 in the Jamaican cohort and IFNα, IP10, VEGF and IgA anti-β2GPI in the Hopkins cohort were all associated with disease activity, with the major contributors being IP10 and VEGF. This further underscores the importance of IFN-induced cytokine activity and vascular pathology in driving disease activity in SLE patients.

Unsurprisingly, several aPL were associated with venous and arterial thrombosis in both cohorts and a commonly accepted theory for thrombus development in aPL-positive patients is the induction of a pro-inflammatory phenotype via cytokines and chemokines decreasing the threshold for thrombosis (5, 6). Indeed, the association of pro-inflammatory IP10, IL-8 and VEGF with venous thrombosis and IP10, IL-8, IL-6 and TNFα with arterial thrombosis indicate that this ‘two-hit’ hypothesis is likely a major mechanism of thrombus development in our SLE patients. Quite a surprising finding was the seemingly reduced risk of arterial thrombosis associated with elevated oxLβ2Ag levels. Previous studies have shown that high serum levels of oxLβ2Ag complexes are common in SLE patients and they may act as atherogenic autoantigens increasing the risk of autoimmune mediated thrombosis and atherosclerosis (27). We are unsure how to explain this discrepancy, however, the protective role of these complexes as well as the moderately strong positive association with vitamin D in our patients hint at a more complex association between these oxidative biomarkers and autoimmune-mediated thrombosis in SLE than previously indicated. This is especially true given the inconclusive reports of the effect of vitamin D levels on the risk of thrombosis in APS and SLE patients (14). Indeed, supplementation of calcium with or without vitamin D has even been shown to modestly increase the risk of cardiovascular events, especially myocardial infarction in a recent meta-analysis (28).

Low vitamin D levels and IL-8 were independently associated with PE/E in our study population. Previous studies have reported higher levels of serum IL-8 in women with pre-eclampsia and intrauterine growth retardation compared to women with normal pregnancies. Serum IL-8 levels were also higher in those with severe versus mild pre-eclampsia (29). Although we saw no correlation of aPL with pregnancy morbidity in our patients, recent in-vitro studies have shown that aPL can induce IL-8 and IL-6 secretion in trophoblasts (30). Vitamin D treatment alone or in combination with low molecular weight heparin has also been shown to attenuate the aPL-mediated proinflammatory response in trophoblast cultures (31). It should be noted however that while currently available clinical evidence indicates no association between hypovitaminosis D and obstetric APS manifestations, a recent cross-sectional study of women with recurrent pregnancy loss reported an association between low vitamin D levels and increased odds of positive aPL (32).

Previous studies in both the Hopkins Lupus Cohort and in a clinical trial have proven that an increase in vitamin D helps global lupus activity (12, 13). Our findings support those of a recently published study, which reported no association between vitamin D levels and the cytokines IFNα, IFNγ, IL2, TNF, IL-10, IL-6, IL4, IL-17, IL21, IL-12p70 and IL23 (33). In addition to IFNα, TNFα and IL-6, we show that vitamin D levels are not associated with IL-1β, IP10, sCD40L, IL-8 or VEGF in either SLE cohort. Based on our results and previous data, the beneficial effect of vitamin D in SLE seems to occur independently of any changes in proinflammatory cytokines. Indeed, vitamin D supplementation was shown to significantly improve disease activity and the urine protein-to-creatinine ratio in the Hopkins cohort patients without a marked change in serological markers.

In the present study, the lack of controlled vitamin D supplementation, the use of previously unfrozen samples that may affect cytokine levels, the cross-sectional nature of the study and the relatively small number of patients as a result of strict inclusion criteria are recognized limitations. However, we show that there was no significant seasonal variation in vitamin D levels and we believe that limiting the extraneous factors that may have affected cytokine and vitamin D levels as well as the high correlation between acute phase reactant cytokines increases the validity or our results. Similarly, the consistency of a majority of our findings in two independent SLE cohorts also suggests that our findings are representative and perhaps some of the noted differences could be explained by a difference in duration of disease in the 2 cohorts. Our results indicate that aPL-mediated pro-inflammatory cytokine production is likely a major mechanism of thrombus development in SLE patients and we provide presumptive evidence of the role IL-8 and hypovitaminosis D play in obstetric pathology in SLE. The molecular mechanisms responsible for the potentially beneficial effects of vitamin D in SLE patients are very likely complex in nature and are probably dependent on several genetic and environmental factors yet to be determined. Further longitudinal studies utilizing larger groups of SLE patients of varying ethnicities and clinical phenotypes are necessary to fully characterize these subtle complexities.

Acknowledgments

All the authors would like to dedicate this paper to the memory of Silvia S. Pierangeli who greatly contributed to the project.

Grant support:

MP is supported by an NIH-NIAMS grant AR43727 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities and EBG and RW are supported by a NIH Grant R01 AR056745-01A1 and a Mallinckrodt-Questcor Fellowship Grant.

References

- 1.Tunnicliffe DJ, Singh-Grewal D, Kim S, Craig JC, Tong A. Diagnosis, Monitoring, and Treatment of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Systematic Review of Clinical Practice Guidelines. Arthritis care & research. 2015;67(10):1440–52. doi: 10.1002/acr.22591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McClain MT, Arbuckle MR, Heinlen LD, Dennis GJ, Roebuck J, Rubertone MV, et al. The prevalence, onset, and clinical significance of antiphospholipid antibodies prior to diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2004;50(4):1226–32. doi: 10.1002/art.20120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer JW, Petri M, Batliwalla FM, Koeuth T, Wilson J, Slattery C, et al. Interferon-regulated chemokines as biomarkers of systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity: a validation study. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2009;60(10):3098–107. doi: 10.1002/art.24803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davas EM, Tsirogianni A, Kappou I, Karamitsos D, Economidou I, Dantis PC. Serum IL-6, TNFalpha, p55 srTNFalpha, p75srTNFalpha, srIL-2alpha levels and disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clinical rheumatology. 1999;18(1):17–22. doi: 10.1007/s100670050045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cuadrado MJ, Buendia P, Velasco F, Aguirre MA, Barbarroja N, Torres LA, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in monocytes from patients with primary antiphospholipid syndrome. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis: JTH. 2006;4(11):2461–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vega-Ostertag M, Casper K, Swerlick R, Ferrara D, Harris EN, Pierangeli SS. Involvement of p38 MAPK in the up-regulation of tissue factor on endothelial cells by antiphospholipid antibodies. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2005;52(5):1545–54. doi: 10.1002/art.21009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berman J, Girardi G, Salmon JE. TNF-alpha is a critical effector and a target for therapy in antiphospholipid antibody-induced pregnancy loss. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2005;174(1):485–90. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cutolo M, Otsa K. Review: vitamin D, immunity and lupus. Lupus. 2008;17(1):6–10. doi: 10.1177/0961203307085879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu PW, Rhew EY, Dyer AR, Dunlop DD, Langman CB, Price H, et al. 25-hydroxyvitamin D and cardiovascular risk factors in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2009;61(10):1387–95. doi: 10.1002/art.24785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amital H, Szekanecz Z, Szucs G, Danko K, Nagy E, Csepany T, et al. Serum concentrations of 25-OH vitamin D in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) are inversely related to disease activity: is it time to routinely supplement patients with SLE with vitamin D? Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2010;69(6):1155–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.120329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruiz-Irastorza G, Gordo S, Olivares N, Egurbide MV, Aguirre C. Changes in vitamin D levels in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: Effects on fatigue, disease activity, and damage. Arthritis care & research. 2010;62(8):1160–5. doi: 10.1002/acr.20186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petri M, Bello KJ, Fang H, Magder LS. Vitamin D in systemic lupus erythematosus: modest association with disease activity and the urine protein-to-creatinine ratio. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2013;65(7):1865–71. doi: 10.1002/art.37953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lima GL, Paupitz J, Aikawa NE, Takayama L, Bonfa E, Pereira RM. Vitamin D Supplementation in Adolescents and Young Adults With Juvenile Systemic Lupus Erythematosus for Improvement in Disease Activity and Fatigue Scores: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Arthritis care & research. 2016;68(1):91–8. doi: 10.1002/acr.22621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piantoni S, Andreoli L, Allegri F, Meroni PL, Tincani A. Low levels of vitamin D are common in primary antiphospholipid syndrome with thrombotic disease. Reumatismo. 2012;64(5):307–13. doi: 10.4081/reumatismo.2012.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. American journal of kidney diseases: the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2002;39(2 Suppl 1):S1–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pierangeli SS, Harris EN. A protocol for determination of anticardiolipin antibodies by ELISA. Nature protocols. 2008;3(5):840–8. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Willis R, Seif AM, McGwin G, Jr, Martinez-Martinez LA, Gonzalez EB, Dang N, et al. Effect of hydroxychloroquine treatment on pro-inflammatory cytokines and disease activity in SLE patients: data from LUMINA (LXXV), a multiethnic US cohort. Lupus. 2012;21(8):830–5. doi: 10.1177/0961203312437270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dawson-Hughes B, Heaney RP, Holick MF, Lips P, Meunier PJ, Vieth R. Estimates of optimal vitamin D status. Osteoporosis international: a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2005;16(7):713–6. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-1867-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGhie TK, DeCeulaer K, Walters CA, Soyibo A, Lee MG. Vitamin D levels in Jamaican patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2014;23(10):1092–6. doi: 10.1177/0961203314528556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sahebari M, Nabavi N, Salehi M. Correlation between serum 25(OH)D values and lupus disease activity: an original article and a systematic review with meta-analysis focusing on serum VitD confounders. Lupus. 2014;23(11):1164–77. doi: 10.1177/0961203314540966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baechler EC, Batliwalla FM, Karypis G, Gaffney PM, Ortmann WA, Espe KJ, et al. Interferon-inducible gene expression signature in peripheral blood cells of patients with severe lupus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(5):2610–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337679100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linker-Israeli M, Deans RJ, Wallace DJ, Prehn J, Ozeri-Chen T, Klinenberg JR. Elevated levels of endogenous IL-6 in systemic lupus erythematosus. A putative role in pathogenesis. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 1991;147(1):117–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gabay C, Cakir N, Moral F, Roux-Lombard P, Meyer O, Dayer JM, et al. Circulating levels of tumor necrosis factor soluble receptors in systemic lupus erythematosus are significantly higher than in other rheumatic diseases and correlate with disease activity. The Journal of rheumatology. 1997;24(2):303–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klarquist J, Zhou Z, Shen N, Janssen EM. Dendritic Cells in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: From Pathogenic Players to Therapeutic Tools. Mediators of inflammation. 2016;2016:5045248. doi: 10.1155/2016/5045248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Camargo JF, Correa PA, Castiblanco J, Anaya JM. Interleukin-1beta polymorphisms in Colombian patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Genes and immunity. 2004;5(8):609–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grenn RC, Yalavarthi S, Gandhi AA, Kazzaz NM, Nunez-Alvarez C, Hernandez-Ramirez D, et al. Endothelial progenitor dysfunction associates with a type I interferon signature in primary antiphospholipid syndrome. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2017;76(2):450–7. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kobayashi K, Lopez LR, Matsuura E. Atherogenic antiphospholipid antibodies in antiphospholipid syndrome. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2007;1108:489–96. doi: 10.1196/annals.1422.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bolland MJ, Grey A, Avenell A, Gamble GD, Reid IR. Calcium supplements with or without vitamin D and risk of cardiovascular events: reanalysis of the Women’s Health Initiative limited access dataset and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2011;342:d2040. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tosun M, Celik H, Avci B, Yavuz E, Alper T, Malatyalioglu E. Maternal and umbilical serum levels of interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in normal pregnancies and in pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine: the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstet. 2010;23(8):880–6. doi: 10.3109/14767051003774942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azuma H, Yamamoto T, Chishima F. Effects of anti-beta2-GPI antibodies on cytokine production in normal first-trimester trophoblast cells. The journal of obstetrics and gynaecology research. 2016 doi: 10.1111/jog.12993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gysler SM, Mulla MJ, Stuhlman M, Sfakianaki AK, Paidas MJ, Stanwood NL, et al. Vitamin D reverses aPL-induced inflammation and LMWH-induced sFlt-1 release by human trophoblast. American journal of reproductive immunology (New York, NY: 1989) 2015;73(3):242–50. doi: 10.1111/aji.12301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ota K, Dambaeva S, Han AR, Beaman K, Gilman-Sachs A, Kwak-Kim J. Vitamin D deficiency may be a risk factor for recurrent pregnancy losses by increasing cellular immunity and autoimmunity. Human reproduction (Oxford, England) 2014;29(2):208–19. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schneider L, Colar da Silva AC, Werres Junior LC, Alegretti AP, Pereira dos Santos AS, Santos M, et al. Vitamin D levels and cytokine profiles in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2015;24(11):1191–7. doi: 10.1177/0961203315584811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]